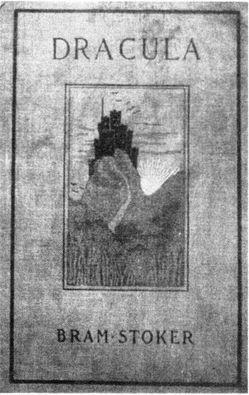

The original 1897 edition of Dracula, with rare original dust wrapper (Rosenbach Museum and Library)

MR. STOKER’S BOOK OF BLOOD

In which a theatre manager pens a tale of surpassing terror,

reviving a Gothic tradition, while indirectly addressing

unspoken tensions between the sexes. An ambiguous

portrait, in the manner of Mr. Wilde, of a celebrated knight and

actor, who is not amused. The unexpected appearance of

Mr. Wilde himself, old rivalries and new revelations,

an inattentive wife, and a lingering malady.

reviving a Gothic tradition, while indirectly addressing

unspoken tensions between the sexes. An ambiguous

portrait, in the manner of Mr. Wilde, of a celebrated knight and

actor, who is not amused. The unexpected appearance of

Mr. Wilde himself, old rivalries and new revelations,

an inattentive wife, and a lingering malady.

IN THE RARE BOOKS ROOM OF A SMALL LIBRARY ON A TREE-LINED street in Philadelphia is a leather slipcase containing a sheaf of mounted note cards, almost a century old but not yellowing—they are an exceptionally high grade of linen stock, the property of Henry Irving’s prestigious Royal Lyceum Theatre in London. The notes contained on them do not pertain to the theatre, and are addressed to no one other than the writer himself. The obsessive culmination of years of research and rumination, they are the working notes of an author of fiction, written in a tiny, often nearly indecipherable pencil scrawl, as if the writer had miniaturized his hand to fit the dimensions of his paper. A psychiatrist, the visitor is told, has spent nearly ten years transcribing, annotating, and interpreting their contents. The frequent cross-outs and marginal additions, trailing-off sentences and one-word reminders vividly depict the fictional process—the writer intuitively steering his unconscious through the refinement of language, discovering the incantatory words and patterns of words that can best describe the troubling image and give it a form in the world.

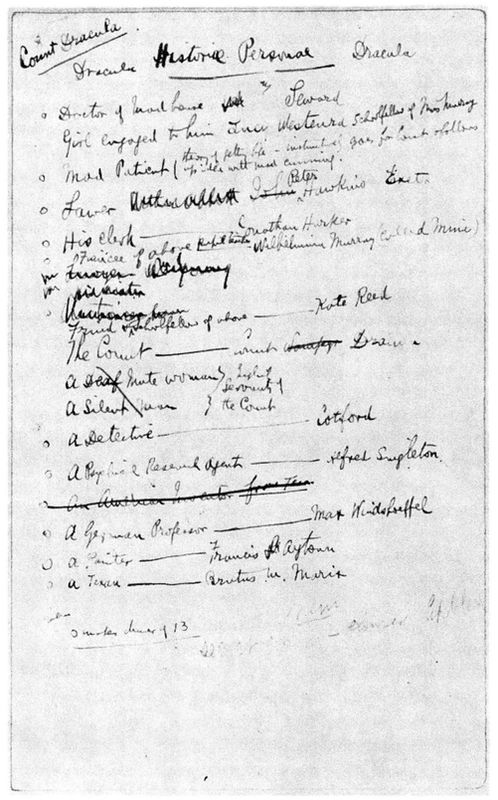

The first page, headed Historiae Personae, lists seventeen embryonic fictional characters. Several names are unfamiliar: Kate Reed, a young Englishwoman; Cotford, a detective; a “psychical research agent” known as Alfred Singleton; a German professor, Max Windshoeffel; an “American inventor from Texas” (discarded in favor of “A Texan—Brutus M. Marix”); a deaf-mute woman and “a silent man,” servants to a mysterious Eastern European count. Other names and characters ring more familiar. Dr. Seward. Lucy Westenra. Wilhelmina Murray. Jonathan Harker. A mad patient (“theory of getting life,” one entry says). And very near the center of the page, the author has scrawled the name of his pivotal character: Count Wampyr. He let it stand for an indeterminate period of time. Somehow, it didn’t work. Perhaps it was too … obvious? He consulted his typewritten notes. He had recorded the Romanian words for Satan and hell, and perhaps considered the possibilities there. Count Ordog? Count Pokol? No, there had to be better. Yes, elsewhere in his notes—something. He struck out the old name and inked in a Wallachian diminutive for “devil,” until then almost unknown in England:

Dracula.

Did it sound right?

He wrote the name again at the top of the page, twice, flanking the original heading. Dracula. Dracula.

Yes.

One final time, then, in the top left corner, boldly underscored:

COUNT DRACULA.

Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula presents one of the most intriguing puzzles in literary history, a book that has attained the status of a minor classic on the basis of its stubborn longevity and disturbing psychological resonance more than on technical or narrative achievement.

Stoker was not an innovator or a stylist of any distinction—even his most partisan critics cannot avoid the word “hack” in connection with his minor works—and yet Dracula remains among the most widely read novels of the late nineteenth century. It has almost never been out of print. Its theatrical and film adaptations are among the most indelible and influential of the twentieth century, and the Dracula legacy has continued into the twenty-first.

A span of centuries is no mean feat for an icon of popular culture, especially for one consistently ignored or denigrated by “respectable” critical authorities. Stoker’s name does not appear in most textbooks of Victorian literature, the stage version is almost never mentioned in theatre surveys (although it enjoyed a popularity in the 1920s rivaling Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Abie’s Irish Rose), and the landmark 1931 film version is usually sidestepped in most film histories. Only through the pirated German silent Nosferatu has Dracula achieved a quasi-respectable niche in modern art circles, and that only by association and in retrospect.

Yet, Dracula persists. As Professor Abraham Van Helsing puts it in the stage and movie versions, “The strength of the vampire is that people will not believe in him.” As Dracula himself notes, in Stoker’s novel, “You think to baffle me, you with your pale faces all in a row, like sheep in a butcher’s. You shall be sorry yet, each one of you! You think you have left me without a place to rest; but I have more. My revenge has just begun! I spread it over centuries, and time is on my side.”

He might as well have been addressing his critics as any fictional enemies.

Superstitions about the restless dead who return to drink the blood of the living are as old as recorded civilization. At its most primitive level, the vampire myth is connected to cannibalism, and to the corollary belief that the devouring of body and blood also imparts a transference of the victim’s strength, courage, or other attributes. Mysterious wasting plagues, catalepsy, and premature burial also contributed to the myth, fostering prescientific explanations for frightening biological phenomena.

As Bram Stoker himself would relate, in a rare interview following the publication of Dracula, the historical basis of vampire legends might be demonstrated by a theoretical case.

Bram Stoker’s working notes for Dracula reveal a plot and characters quite different from those that emerged in the finished book. (The Rosenbach Museum and Library)

A person may have fallen into a death-like trance and been buried before the time. Afterwards the body may have been dug up and found alive, and from this a horror seized upon the people, and in their ignorance they imagined that a vampire was about. The more hysterical, through excess of fear, might themselves fall into trances in the same way; and so the story grew that one vampire might enslave many others and make them like himself. Even in the single villages it was believed that there might be many such creatures. When once the panic seized the population, their only thought was to escape.

Modern psychoanalytic theory, as classically argued by Ernest Jones in On the Nightmare (1931), posits the genesis of vampire legends in the universal experience of the nightmare, and its interpretation by early man as a literal visitation by a life-draining demon. From the psychoanalytic viewpoint, the suppression of sexual feeling by social or institutional strictures gave rise to the popular belief in the incubus or succubus, male and female spirits believed to have sexual relations with sleeping victims. Outbreaks of incubation, reported as if they were actual medical plagues rather than psychosexual delusions, were widespread in cloisters from the Middle Ages onward.

Like the incubus, the vampire is a spectre that frequently rises at the boundaries of social, religious, and sexual conformity. Excommunicants, it was long believed, could expect to return from death with a terrible thirst. Illegitimacy, incest, and homosexuality have long had implicit and explicit links to the vampire in legend and literature. In Romania, the vampire was believed to be the result of an illegitimate birth to parents who were themselves illegitimate. Legends involving the return of dead relatives have been observed to contain distinct undertones of incestuous guilt. And the bisexuality and homosexuality of vampires has, by the late twentieth century, become a virtual donnée; the modern image of the female vampire especially is almost always tinted by lesbianism. Significantly, the diatribes of modern-day crusaders against sexual minorities, with their fearful fantasies of seduction, transformation, and unholy corruption, find a distinct parallel in antique tracts on the exorcism of vampires. When the definitive anthropological history of the AIDS epidemic is finally written, the irrational, vampire-related undercurrents

of scapegoating, blood superstition, and plague panic will no doubt be prominent considerations.

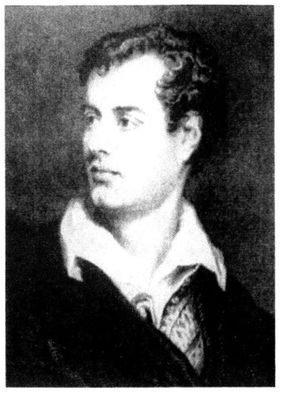

Romantic vampire prototype: George Gordon, Lord Byron, seen in a 1904 engraved frontispiece to his collected works (Author’s collection)

Prior to the Romantic revolution of the early 1800s, the popular image of the vampire was that of walking, predatory carrion. Byron, whose mystique would leave an indelible, transforming mark on the evolution of the vampire image, first dealt with the subject in a curse contained in his poem “The Giaour” (1813):

But first on earth, as Vampyre sent,

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent;

Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet, which perforce

Must feed thy livid, living corse,

Thy victims, ere they yet expire,

Shall know the demon for their sire;

As cursing thee, thou cursing them,

Thy flowers are withered on the stem.

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent;

Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet, which perforce

Must feed thy livid, living corse,

Thy victims, ere they yet expire,

Shall know the demon for their sire;

As cursing thee, thou cursing them,

Thy flowers are withered on the stem.

Byron implies a tragic, ambivalent dimension to vampirism that was hitherto unknown, but which would exert a major influence on future writers. The author himself was the model for an autobiographical novel by Lady Caroline Lamb, Glenarvon (1816), in which she depicted Byron as a libertine, Ruthven Glenarvon, fatal to women, who is finally carried away by supernatural forces.

A close friend of Byron’s, Dr. John Polidori, did Lamb one better by borrowing the nom de clef for his own Romantic thriller. In 1819, Polidori’s short story “The Vampyre” first introduced several of the motifs that would forever link Byron with vampires—on its first publication, in fact, authorship was fraudulently attributed to Byron. (Goethe, who had dealt with Illyrian vampire legends in his Bride of Corinth in 1797, was completely taken in, and called “The Vampyre” Byron’s finest work.) The story concerns Lord Ruthven, a libertine in the Byronic mode. Killed in Greece and returned to London as a vampire, he relentlessly stalks the sister of his former friend, Aubrey. The friend is restrained by a solemn oath made to Ruthven before his death not to reveal his preternatural state, and watches horrified as Ruthven pursues, seduces, marries, and kills his sister. While the blood-drinking is more metaphorical than explicit, the story provided a narrative blueprint for the major vampire sagas that were to follow. Significantly, the story was a product of the celebrated literary house party that also inspired Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein; as we will see, the Frankenstein and Dracula images have been linked in imagination and commerce ever since.

While it was well known in literary circles that Polidori was the author, Byron’s was the bankable name (his scandalous love affairs were then the sensation of Europe), and the story was repeatedly attributed to him in numerous editions and translations and even in collections of his work.

In Paris, where the projected magic lantern demons of the Fantasmagorie had thrilled the public at the turn of the previous century, the theatrical possibilities of Polidori’s tale were quickly grasped. Charles Nodier, under whose aegis an unauthorized sequel, Lord Ruthwen ou les Vampires, by Cyprien Bérard, had been published in February 1820, collaborated with Achille Jouffroy and Carmouche on the first vampire stage melodrama, Le Vampire, presented at the

Théâtre Porte-Saint-Martin in June of the same year. The production was reportedly thrilling and controversial—and an immense success. The public appetite for vampire dramas prompted a veritable stampede of imitations. According to Montague Summers, vampire chronicler extraordinaire, “Immediately upon the furore [sic] created by Nodier’s Le Vampire … vampire plays of every kind from the most luridly sensational to the most farcically ridiculous pressed on to the boards. A contemporary critic cries: ‘There is not a theatre in Paris without its Vampire! At the Porte-Saint-Martin we have Le Vampire; at the Vaudeville Le Vampire again; at the Varietes Les Trois Vampires ou le clair de la lune.’” Other Parisian stage vampires of 1820 were seen in Encore un Vampire, Les Étrennes d’un Vampire, and Cadet Buteux, vampire (the published libretto carried the motto: “Vivent les morts!”).

Readers of Anne Rice’s best seller The Vampire Lestat (1985) will no doubt recognize in this real-life vampire fever Rice’s inspiration for her Theatre des Vampires of the same period. Rice’s actors, however, are true vampires, who share a Romantic sensibility that could put Byron to shame. Steeped in French art and culture, The Vampire Lestat illustrates the major contribution of the city of Paris in particular to the development of the modern vampire image. Paris in the days before the grand boulevards and gaslight was a dangerous place full of narrow streets, menace, and shadows. At night, fearful pedestrians carried torches. After sunset, even the open expanses of the Champs Elysees and the Luxembourg Gardens “were concealed by an almost impenetrable darkness.” Such was the Paris whose citizenry would respond en masse to the new, consummate theatre of shadows, the vampire melodrama.

Alexandre Dumas père, on his first night as a citizen of Paris in 1823, decided to attend a revival of Le Vampire at the Porte-Saint-Martin. Obtaining admission was not a simple matter, but the young Dumas, fresh from the provinces, was determined; seeing Le Vampire became a ritual of cosmopolitan validation. On his first attempt he was ejected from the raucous pit in an altercation with Frenchmen who took exception to the mulatto curl of his hair.

Nonetheless, Le Vampire intrigued Dumas, and he tried again, this time buying an orchestra ticket. He was seated without incident, and enthralled by the play. However, a certain strange gentleman beside

him was vocally and unremittingly critical of the proceedings. According to Dumas’s biographer Herbert Gorman, “He groaned, made audible remarks of the most caustic nature, was angrily hissed by his neighbors.” In time the gentleman created a scene and was ejected from the theatre. Dumas learned later that the gentleman was one of the play’s authors, Charles Nodier himself.

Dumas’s life and adventures in Paris were to be framed by the story of the vampire Lord Ruthven; nearly thirty years later, his own elaborate adaptation of the Polidori tale would be his final offering under his own name to the Paris stage.

Meanwhile, the French play had been adapted into English by James Robinson Planché as The Vampire, or, The Bride of the Isles and presented to packed houses in August 1820 at the English Opera House, later to be called the Lyceum. To please the management, the author adapted the story to a Scottish setting, with bagpipes and kilts, though the vampire legend was not indigenous to Scotland. Planché would have preferred an Eastern European setting, but the management had a full complement of Scottish costumes in stock and was determined to use them. The production employed a special trapdoor to permit the sudden disappearance of the vampire in plain view of the audience; this innovative device—called a “vampire trap” in theatrical parlance—was destined for an appropriate revival a century later in dramatizations of Dracula.

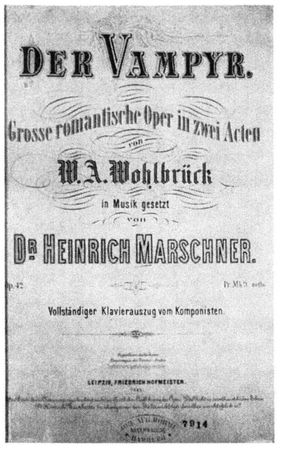

On March 28, 1828, an operatic adaptation of the Nodier play, entitled Der Vampyr and setting the story in Hungary, was produced at Leipzig, with libretto by Wilhelm August Wohlbruck and music by Heinrich August Marschner. (A record of an earlier, unrelated opera, Il vampiri by Neapolitan composer Silvestro di Palma, notes its production in Italy in 1800.) James Robinson Planché made a free English adaptation of the Marschner work in 1829, which was produced at the Lyceum. Ruthven’s nationality had changed yet again; this time he was a Wallachian boyard.

Dion Boucicault’s The Vampire (1852), another Polidori-inspired drama, had three acts set in three centuries, including the future, and so must qualify as an early attempt at science fiction as well as horror. One notably harsh London critic savaged the effort, stating that he had no objection to “an honest ghost” but voiced his strenuous objection to “an animated corpse which goes about in Christian attire,

and although never known to eat, or drink, or shake hands, is allowed to sit at good men’s feasts; which renews its odious life every hundred years by sucking a young lady’s blood, after fascinating her by motions which resemble mesmerism burlesqued … such a ghost as this passes all bounds of toleration.”

Title page to Marschner’s opera Der Vampyr (1843), which created an indelible image of the romantic vampire (Author’s collection)

Queen Victoria, however, found Boucicault’s performance more than tolerable. “Mr. Boucicault, who is very handsome and has a fine voice, acted very impressively. I can never forget his livid face and fixed look … . It quite haunts me.” But upon a repeat visit, she found the play itself an ordeal. “It does not bear seeing a second time,” she wrote, “and is, in fact, very trashy.”

Trashy or not, The Vampire was nonetheless a success. Revived under the title The Phantom, it was the first vampire play exported from England to America, with Boucicault reprising the lead role. He may also have been the first actor to incorporate the appearance of a bat into his costume and performance. Odell’s Annals of the New York Stage cites Mrs. M.E.W Sherwood’s 1875 recollection of Boucicault’s characterization, “a dreadful and weird thing played with immortal

genius. That great playwright would not have died unknown had he never done anything but flap his bat-like wings in that dream-disturbing piece.”

The vampire in prose had already received an energy tranfusion with the appearance in 1847 of James Malcolm Rymer’s Varney the Vampyre: or, The Feast of Blood. Subtitled “A Romance of Exciting Interest,” this overheated nine-hundred-page “penny dreadful,” originally sold in cheap installments, is the definition of hack writing. Stuffed with prose that transcends the merely purple in a seeming quest for the ultraviolet, and weirdly shifting tenses (the present-tense passages read like scraps of screenplays), Varney today retains an odd, campy fascination.

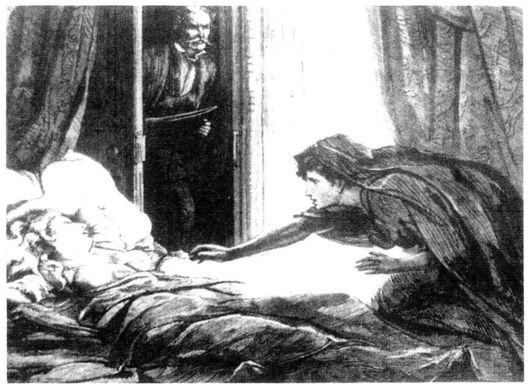

The figure turns half-round, and the light falls upon the face. It is perfectly white—perfectly bloodless. The eyes look like polished tin; the lips are drawn back, and the principal feature next to those dreadful eyes is the teeth—the fearful-looking teeth—projecting like those of some wild animal, hideously, glaringly white, and fang-like. It approaches the bed with a strange, gliding movement. It clashes together the long nails that literally appear to hang from the finger-ends. No sound comes from its lips. Is she going mad—that young and beautiful girl exposed to so much terror?

In an evident attempt to increase the word count (and, thus, the author’s income), Rymer’s vampire pauses at regular intervals en route to his grisly breakfast-in-bed, hypnotically fascinating his victim with dead, yet glittering, eyes. “The figure has paused again, and half on the bed and half out of it that young girl lies trembling. Her long hair streams across the entire width of the bed. As she has slowly moved along she has left it streaming across the pillows. The pause lasted about a minute—oh, what an age of agony.” And, finally:

With a sudden rush that could not be foreseen—with a strange howling cry that was enough to waken terror in very breast, the figure seized the long tresses of her hair, and twining them round his bony hands he held her to the bed. Then she screamed—Heaven granted her then power to scream. Shriek followed shriek in rapid succession. The bed-clothes fell in a heap by the side of the bed—she was dragged by her long silken hair completely on to it again. Her beautifully rounded limbs quivered with the agony of her soul. The glassy, horrible eyes of the figure ran over that angelic form with a hideous satisfaction—horrible

profanation. He drags her head to the bed’s edge. He forces it back by the long hair still entwined in his grasp. With a plunge he seizes her neck in his fang-like teeth—a gush of blood, and a hideous sucking noise follows. The girl has swooned, and the vampyre is at his hideous repast!

The plot is endlessly convoluted, the scenes and dialogue padded for length, as Sir Francis Varney leaves a trail of blood and verbiage in his wake, finally to call off the proceedings abruptly by leaping into the cauldron of Mount Vesuvius. A far cry from literature, Varney nonetheless strengthened the popular image of the bloodsucking fiend scrabbling at the bedroom windows of virtuous Victorian virgins. Its woodcut illustrations notably introduced a black cape as a standard feature of vampire fashion—a possible influence on Boucicault’s bat-cloak—and its depiction of an un-dead Eastern European aristocrat arriving in England by way of a stormy shipwreck foreshadowed much that was to come.

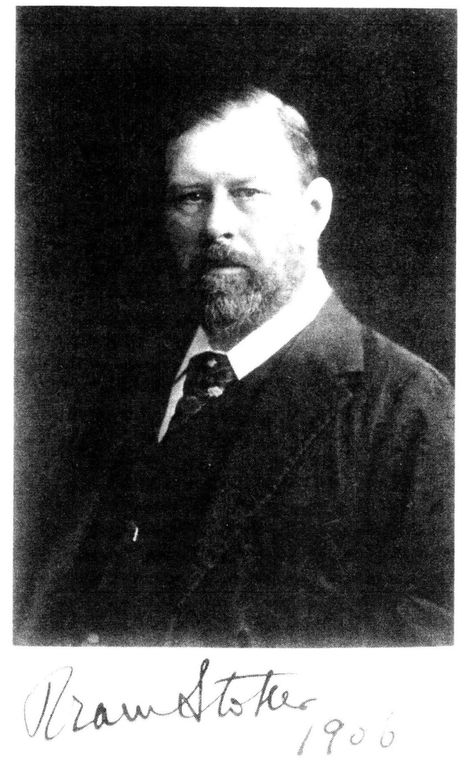

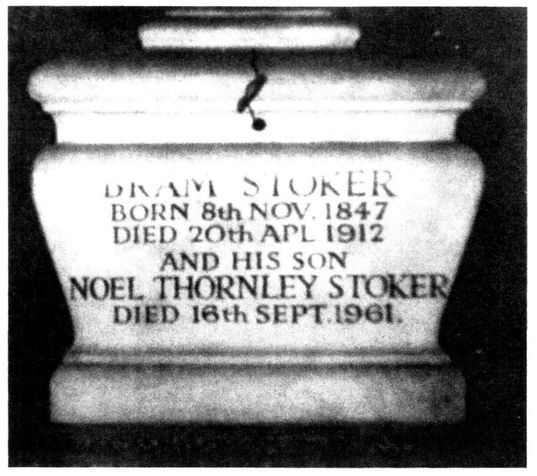

The publication of Varney the Vampyre coincided with another milestone in vampire literature: the birth in Dublin of Abraham Stoker.

Born in November 1847, Bram Stoker began life as a sickly child and persisted in an invalid state, never walking until the age of seven. Psychoanalytic commentators have made much of the possible effect of this prolonged illness on his imagination and his writing, but only a few have questioned whether the illness itself was psychological. Considering the robust athleticism of Stoker’s later years, recorded in his own memoirs and in the accounts of others, the sudden disappearance of a crippling congenital condition with no lasting effects seems odd indeed. The episode evokes case histories of traumatized children who refuse to speak, or of “hysterical” paralysis and blindness in adults. Could Bram the boy have acted out a conflict in a psychosomatic fashion? A child barely out of infancy, after all, cannot write horror novels to sublimate his terrors. It may be worth noting that as Bram reached school age and discovered books, his “paralysis” vanished. “I was naturally thoughtful,” he wrote in 1906, “and the leisure of long illness gave opportunity for many thoughts which were fruitful according to their kind in later years.”

Stoker didn’t relate the substance of those thoughts, what he read as a boy, or much else about his childhood, which has led a significant number of modern critics and biographers to fill the vacuum with a spectrum of speculation, informed and otherwise. Because Dracula is the primary reason anybody today cares about Bram Stoker, there has been an unfortunate tendency to reduce every known fact (and quite a few unknown facts) about Stoker’s life to a facile “explanation” of Dracula. Was Stoker the victim of childhood sex abuse? What are vampires, after all, if not a variety of sexual predator? Did Stoker’s mother’s detailed and harrowing accounts of an Irish cholera epidemic, including a true story of a presumably dead man who woke up in his coffin, and stories of starving Irishfolk driven to drink the blood of cattle for sustenance predispose her son to an interest in vampires? Did some primal glimpse of a vagina during menstruation prompt the boy to fantasize about bloody female mouths?

Illustration for Varney the Vampyre (1847), which introduced the black cape as an essential feature of vampire couture (Author’s collection)

Since armchair psychologizing at a century’s remove can be a fool’s game, it may be far more productive to look for Dracula’s roots in literary antecedents. One piece of writing that definitely captured Stoker’s imagination was Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s elegant novella Carmilla (1871), in which tasteful lesbianism added new spice to the literary vampire stew. Le Fanu, another Dubliner whose highly crafted ghost stories would likely also have been well known by Stoker, tells a dreamlike story in which childhood memories, vampirism, and same-sex love unfold with the surreal logic of a fairy tale. Laura, a young woman living in a kind of storybook castle in the Austrian province Styria, narrates the story. She has a strange memory from early childhood of a night visitation by a beautiful girl, carrying a distinct flavor of vampirism to the reader if not the teller. Years later, the girl appears to her again in the form of Carmilla, a mysterious young lady who joins her household under a cloud of secrecy and intrigue. Carmilla remembers the same dream. The two young women form a powerful bond: “Sometimes after an hour of apathy, my strange and beautiful companion would take my hand and hold it with a fond pressure, renewed again and again; blushing softly, gazing in my face with languid and burning eyes, and breathing so fast that her dress rose and fell with the tumultuous respiration. It was like the ardor of a lover; it embarrassed me; it was hateful and yet overpowering; and with gloating eyes she drew me to her, and her hot lips travelled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, ‘You are mine, you shall be mine, and you and I are one for ever.’”

Le Fanu’s hypnotic cadences elevate Carmilla to something approaching a prose poem, and it is without question one of the most distinguished and influential pieces of vampire literature in English. The narrator gradually discovers Carmilla Karnstein’s identity as a vampire in a narrative in which identity itself becomes blurred and

ambiguous. There is a strong undercurrent of the doppelganger in the story, and the poignant irony that Carmilla (who, we learn, is also known variously as Marcilla and Millarca) is herself victim as well as predator.

It is not known precisely when Stoker encountered Carmilla; his biographers and critics alike take the matter mostly on faith, based on the story’s unmistakable echoes in Dracula, as well as his notes, which specified “Styria” as Dracula’s homeland. His notes otherwise contain no allusions to fictional vampires, but the finished book would be full of textual echoes. Besides Carmilla, literary vampire tales that could have arrested his attention as a young man included “Wake Not the Dead” (circa 1800, usually attributed to Johann Ludwig Tieck), and Theophile Gautier’s “La morte amoreuse” (1843), about a priest obsessed and seduced by a vampire-courtesan named Clarimonde (an intriguing near-anagram of “Carmilla,” suggesting an influence on Le Fanu). Too often overlooked, or underrated, as a rather obvious source for Dracula is the anonymous German tale “The Mysterious Stranger” (translated into English in 1860), concerning a vampire knight in a ruined Carpathian castle. Azza von Klatka’s cadaverous appearance belies a terrible strength. He has the power to command wolves, and sleeps in a coffin box in a crumbling chapel—the sight of him thus transfixes the beholder. He is never seen eating. Klatka grows younger and ruddier as a young female victim progressively weakens, her strange neck wound refusing to heal. Finally, a wise, older man well versed in the ways of vampires enlists her assistance in destroying Klatka in his coffin, thereby saving her life.

Strange bedfellows: an illustration for Carmilla (1871) (Author’s collection)

It’s possible that Stoker read some of these stories in his youth, or otherwise had an abiding fascination with the supernatural, but the man who would achieve worldwide fame as the author of “the weirdest of weird tales” gave no clue to such predilections while a student at Trinity College, Dublin (1864–70). Stoker’s interests and activities were wide, and he excelled athletically and academically, eventually graduating with honors in pure mathematics. From an early age, Stoker was drawn to the exaggerated reality of the debating team and the theatre, to literature and to individuals who embodied dramatic, archetypal qualities. At Trinity, he positively worshipped Walt Whitman, defending the poet at the height of the controversy over Leaves of Grass and writing him long, emotionally revealing letters. At the age of twenty-four, Stoker articulated to his American hero a radical yearning for fusion transcending convention and gender: “How sweet a thing it is for a strong healthy man,” Stoker wrote, describing himself, “with a woman’s eyes and a child’s wishes to feel that he can speak so to a man who can be if he wishes father and brother and wife to his soul.” At the same time, Stoker assured Whitman—or perhaps reassured himself—that he was basically “conservative.” Whitman responded, and they eventually met.

But the most significant relationship of Stoker’s life—indeed, most commentators agree that it eclipsed even his marriage—was his friendship with the celebrated actor Henry Irving, whom he served as manager and confidante for nearly thirty years. In 1876 Stoker was working as a civil servant in Dublin, but also contributing unpaid theatre reviews to the Dublin Mail, a publication partly owned by J. Sheridan Le Fanu. His glowing appraisals of the Shakespearean

actor Henry Irving, who felt unappreciated in Ireland, finally prompted the celebrated thespian to request an introduction. After their second dinner together, Irving recited a grisly dramatic monologue, “The Dream of Eugene Aram,” in which a murderer is overcome by guilt and the fear of God. Following the recitation, Irving himself collapsed into a chair. “Art can do much,” Stoker wrote in retrospect, “but in all things even in art there is a summit somewhere. That night for a brief time in which the rest of the world seemed to sit still, Irving’s genius floated in blazing triumph above the summit of art.” As for Stoker himself, “I burst into something like hysterics.”

Irving was deeply impressed (“Soul had looked into soul!” wrote Stoker. “From that hour began a friendship as profound, as close, as lasting as can be between two men.”) and a few seasons thereafter claimed the young man as his own, at least professionally. Stoker assumed the acting managership of Irving’s new venture, London’s Lyceum Theatre, in December 1878, to the dismay of his practical family, who disapproved of his theatrical interests and of theatrical people. But to Stoker, Irving and the Lyceum became a passion—so much so that his appointment actually preempted his honeymoon. Later, it would become almost a cliche among his chroniclers that Stoker’s “real” marriage was to Irving and not to his bride, the beautiful Florence Balcombe from Dublin’s seaside suburb, Clontarf, where Stoker himself was born.

Stoker’s responsibilities at the Lyceum were both heady and overwhelming. He oversaw the artistic and administrative aspects of the new theatre, and acted as Irving’s buffer, goodwill ambassador, and hatchet man. He learned the pleasures of snobbery. Author Horace Wyndham, one of Stoker’s few acquaintances who later published his impressions, recalled in 1923, “To see Stoker in his element was to see him standing at the top of the theatre’s stairs, surveying a ‘first night’ crowd trooping up them. There was no mistake about it—a Lyceum première did draw an audience that really was representative of the best of that period in the realms of art, literature and society. Admittance was a very jealously guarded privilege. Stoker, indeed, looked upon the stalls, dress circle and boxes as if they were annexes to the Royal Enclosure at Ascot, and one almost had to be proposed and seconded before the coveted ticket would be issued.”

Stoker accompanied Irving on his many tours to America and made scouting expeditions to plan the same. Since it is frequently asserted that Irving was a metaphorical Dracula who exploited and drained his manager, it should be noted that Stoker’s dedication to Irving was scarcely without compensation—he was paid handsomely from the Lyceum coffers. Records of the 1893–94 American tour showed that he drew a weekly salary of $1,694, or approximately £350, well beyond a merely comfortable wage. By comparison, Irving’s actors, who were considered well paid, earned only two pounds, ten shillings. Even a rising luminary like Ethel Barrymore, who played at the Lyceum in 1897, commanded only seven pounds per week. Allowing that Stoker’s pay may well have included significant out-of-pocket reimbursement for all manner of company expenses, the gap between executive salaries and those of frontline workers at the time of Dracula seems positively vampiric.

Their coffers presumably well lined, the Stokers acquired a comfortable house on Cheyne Walk, one of the most fashionable streets in Chelsea, where their neighbors and guests included the likes of James McNeill Whistler, W. S. Gilbert, Mark Twain, John Singer Sargent, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. But a glittering social life may have come at the cost of a Faustian bargain: Stoker’s working relationship with Henry Irving proved less a Whitmanesque union of souls than an unending exercise in institutional politics. According to Horace Wyndham, “Irving—who, despite his general astuteness, was a pretty poor judge of character, and would believe anyone who flattered him sufficiently—surrounded himself with a greedy host of third-rate parasites at the expense of the theatre’s not inexhaustible revenues … .

“Stoker, who had more brains than the entire pack put together, hated the sight of them. He once told me that if he could have made a clean sweep of the lot, the Lyceum treasury would have been saved some thousands a year. Irving, however, would not listen … . He thought it enhanced his dignity to be surrounded by a courtier-like crowd of sycophants. As a matter of fact, it merely made people laugh at him.” Almost unbelievably, during this period of relentless professional stress and pressure, Stoker’s literary output did not suffer, but increased markedly.

Before Dracula, Stoker had already published six books, including the 1879 government handbook The Duties of the Clerks of Petty Sessions

in Ireland; Under the Sunset (1881); and three novels: The Snake’s Pass (1890); The Watter’s Mou’ and The Shoulder of Shasta (both 1895). The novels were romantic adventure tales; Stoker’s only previous excursions into fearful fiction had been a four-part serial called The Chain of Destiny (1875), but perhaps most prophetically, the disturbing collection of “children’s stories,” Under the Sunset, subsidized, at least in part, by Stoker himself. The writer’s decidedly morbid turn of mind is intimated in the dedication of the volume to his three-year-old son, Noel, “whose Angel doth behold the face of THE KING.”

The king, as we soon learn from the stories, is the King of Death.

Under the Sunset is full of darkness and shadows, images of infanticide and plague, and anticipates many of Stoker’s later preoccupations in his “adult” novels of horror. One of the collection’s strongest stories, “The Castle of the King,” concerns the mythic journey of a poet to rescue his wife from a skull-shaped castle in the kingdom of death; love and fatality merge in a single, dreamlike vision.

The theme of the divided self, which would play a prominent role in Stoker’s later work, was presented with a vengeance in one of the author’s least-known and most bizarre stories, “The Dualitists; or, the Death Doom of the Double Born,” published in 1887. Two malicious little boys, Harry and Tommy, find in each other a malignant soul mate and together play an escalating game called “Hack” which begins with the terrorizing of neighborhood girls. “It was a thing of daily occurrence for the little girls to state that when going to bed at night they had laid their dear dollies in their beds with tender care, but … when again seeking them in the period of recess they had found them with all their beauty gone, with arms and legs amputated and faces beaten from all semblance of human form.”

The boys spend considerable time comparing, rubbing together, and brooding over their blades. “So like were the knives that but for the initials scratched in the handles neither boy could have been sure which was his own.” Soon they tire of vandalism and grow bloodthirsty, and take to murdering all the neighborhood’s pets, using rabbits and other small bound animals as bludgeons. When all the available fauna have been sacrificed, they turn their interest toward a pair of baby twins, Zachariah and Zerubbabel Bubb (“They are exactly equal! This is the very apotheosis of our art!”). They lure the

twins into a fatal game on a stable roof, bloodily beating each with the other. That Stoker’s manner of narration is clearly intended to be comic adds another level of horror to the proceedings. When the Bubb parents take a shot at the young killers, they miss and blow the heads off their own children instead. Tommy and Harry gleefully play catch with the headless trunks of the twins and finally hurl them down to their parents, who are killed by the falling corpses. On the boys’ testimony, the Bubbs themselves are charged posthumously with infanticide and suicide, and are buried with stakes driven through their bodies. Tommy and Harry, we learn, are precociously knighted.

“The Dualitists” is sadistic and shocking, all the more so for its author’s snickering pleasure in its telling. The story blends raging infantile aggression with highly controlled prose, and implies volumes about the paradoxical dynamics of Stoker’s literary imagination on the eve of his magnum opus.

Just how early the vampire theme attracted Stoker is not known; the working notes that survive date from 1890. Stoker was also inspired to an extent (and only to an extent) by accounts of the fifteenth-century Wallachian prince Vlad “The Impaler” Tepes (1431-1476), whose ferocious father had earned the sobriquet of Dracul or devil. The son, even more bloodthirsty than his progenitor, came to be known as the son of the devil—Dracula. But trappings of historicity were only atmosphere in an otherwise completely fictive invention. There is no evidence that Stoker did any significant research on Vlad besides transcribing some brief passages from William Wilkinson’s An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (1820). Wilkinson makes no mention of Vlad’s penchant for impaling his enemies, and neither does Stoker. The grisly practice is sometimes cited as a link between history and the folk remedy of vampire staking, but it is no more than a curious coincidence—nowhere in the historical record is Vlad connected to the vampire tradition in folklore. The depiction of vampires as predatory artistocrats is a nineteenth-century literary conceit, concretized by Byron.

A major source for Stoker’s understanding of folkloric vampires was Emily Gerard’s essay, “Transylvanian Superstitions” (1885), later incorporated into her two-volume 1888 book The Land Beyond the Forest (its title being a loose translation of the word “Transylvania”—“across the forest”). Gerard cites multiple variants of the Romanian devil-word in regional superstition: the Gregynia Drakuluj (devil’s garden), the Gania Drakuluj (devil’s mountain), and the Yadu Drakuluj (devil’s hell or abyss). Beyond impressions of Transylvanian folkways gleaned from Gerard, Stoker also expressed a familiarity with vampire legends in “China, Iceland, Germany, Saxony, Turkey, the Chersonese, Russia, Poland, Italy, France and England, besides all the Tartar communities.”

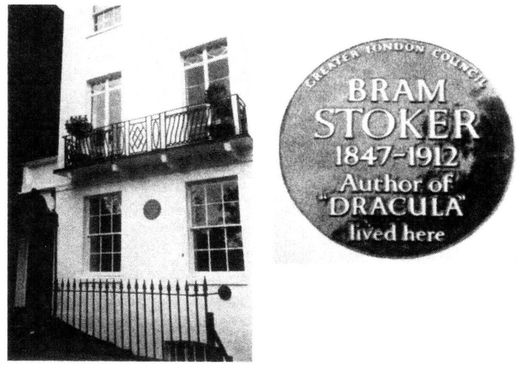

Bram Stoker in a 1906 publicity portrait for his Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving (Author’s collection)

Stoker claimed to have spent about three years writing Dracula, though he told an interviewer he had the story much longer in mind. While much of his early conception of the story would be jettisoned, one vivid scene, teeming with sexual ambiguity, persisted from conception to publication: “young man goes out—sees girls one tries—to kiss him not on the lips but throat. Old Count interferes—rage and fury diabolical. This man belongs to me I want him.”

Without specifying this scene, Stoker would later claim (as a kind of family joke, according to his son), that Dracula had its genesis in a terrifying dream brought on by a “too generous helping of dressed crab at supper one night,” perhaps a tongue-in-cheek attempt to link Dracula to Mary Shelley’s famous (though, like Stoker’s, not entirely credible) account of her nightmare inspiration for Frankenstein. Robert Louis Stevenson had similarly claimed a dream-inspiration for “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

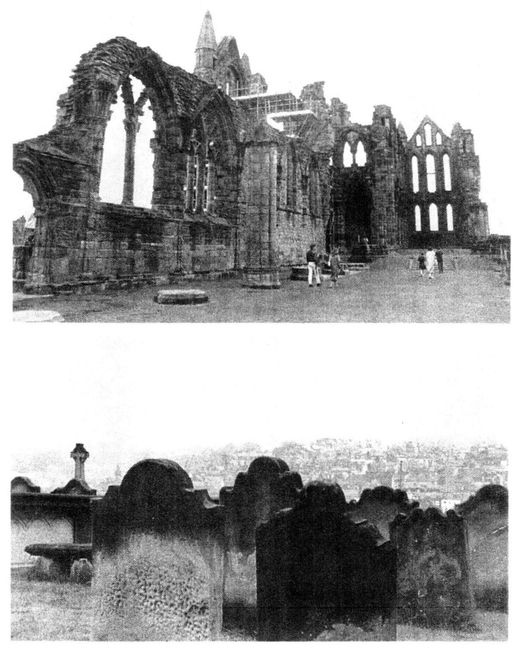

Stoker’s first notes were made before and during a seaside vacation at Whitby—then, as today, a uniquely picturesque fishing village in North Yorkshire where he would have been likely well acquainted with crab, whatever its portions. Whitby emerged as a key location in the novel, its ruined abbey and windswept cliffside cemetery providing an irresistible ambience for a vampire visitation. An actual shipwreck in Whitby Harbor in 1885 provided the template for Dracula’s spectral landing on British soil. The real ship was called the Dmitry; Stoker renamed it the Demeter, while anagramming the real ship’s port of sail, Narva, as “Varna.” He made detailed notes of tombstone inscriptions in the abbey’s cemetery, and recorded colorful examples of local dialect. And it was in the Whitby subscription library that Stoker came across the Wilkinson book and the name “Dracula.”

The working notes for Dracula, now owned by the Rosenbach Library and Museum in Philadelphia, outline a messy potboiler with far too many characters and an overcomplicated plot. At just what point these crystalized into tight, archetypal drama is not precisely known, but the notes span the years from 1890 to 1896. The Dracula notes, with their abundance of overlapping characters, offer one of the few tangible insights into Stoker’s working methods and suggest a connection between theme and process. Just as his finished work deals time and again with doubles and dualities, so too does his working imagination split, merge, and shuffle fictional identities, as if testing the myriad possibilities. For example, Dracula’s now famous nemesis, Abraham Van Helsing, originally had his identity divided among three preliminary characters. Given Stoker’s amazing literary output—eighteen books, most completed during a period of all-consuming professional commitment to the Lyceum Theatre—it is not unreasonable to assume that he worked rapidly, with more feverish inspiration than careful design.

Whitby Abbey, North Yorkshire, and its windswept cemetery. Both are featured prominently in Dracula. (Photos by the author)

Commemorative plaque on the “Bram Stoker Seat” overlooking Whitby Harbor, from which many of Dracula’s real-life locations can still be viewed (Photo by the author)

The only direct accounts of Stoker writing Dracula were made by his wife, Florence, and his son, Noel, long after the fact. Noel Stoker told biographer Harry Ludlam that his father was “very testy” during the book’s composition. In 1926, Florence wrote, “My late husband used to read his stories over to me as they were written, and ‘Dracula’ was by no means least among those which revealed to me the supernormal imagination of the writer.” The following year, a press story

quoted some further recollections: “When he was at work on ‘Dracula,’ we were all frightened of him. It was up on a lonely part of the east coast of Scotland, and he seemed to get obsessed by the spirit of the thing. There he would sit for hours, like a great bat, perched on the rocks of the shore or wander alone up and down the sandhills, thinking it out.”

The seaside location was Cruden Bay, where Stoker and his family first vacationed in the summer of 1893. It is likely that a working manuscript of the novel began to take shape that year, since Stoker claimed to have spent three years formally writing the book, and the 1893 calendar coincides with Dracula’s internal dating and several contemporary references.

It is not known how many drafts of the book Stoker composed, or what sort of editorial guidance he might have received in the process. But Dracula is clearly the most professionally crafted piece of fiction to appear under Stoker’s name, giving rise to questions of its full paternity. H. P. Lovecraft, America’s literary master of the dark fantastic, recalled in a 1932 letter, “I know an old lady who almost had the job of revising ‘Dracula’ back in the early 1890s—she saw the original ms., & says it was a fearful mess. Finally someone else (Stoker thought her price for the work was too high) whipped it into such shape as it now possesses.” Stoker extensively revised the final typescript by hand, and by cut-and-paste transpositions, but the existence of a typist, editor, or book doctor remains an open question.

It has been assumed that Stoker’s comfortable employment at the Lyceum allowed him the leisure to polish the novel to a higher gloss than any of his other novels. But in fact, Stoker completed Dracula during a period of serious financial pressure, brought on by the unexpected calling-in of a long-standing debt, an imprudently large investment in the publishing firm of Heinemann and Balestier, and, finally, the purchase of the leasehold on his new home at 18 St. Leonard’s Terrace, Chelsea, on money borrowed from the prestigious bank Coutts, which would now extend him no further credit. In June 1896, a year before Dracula’s publication, he wrote a difficult, humiliated letter to his close friend Hall Caine, the best-selling novelist, asking for a personal loan of six hundred pounds, promising that “if the new book comes out well at all the first money I get will go to pay the debt.” He would ultimately repay Caine not from

Dracula earnings, but instead by signing over a seven-hundred-pound insurance policy.1

In other words, Stoker badly needed a literary success and could have had reason to be highly motivated to seek a hands-on editor. Some have suggested that Caine himself helped polish the book—indeed, Caine critiqued Stoker’s work before and after Dracula, and Dracula was ultimately dedicated to Caine (“To my dear friend Hommy Beg,” a Manx nickname meaning “Little Tommy”; Caine’s full given name was Thomas Hall Caine). Stoker himself provided editorial assistance on at least two of Caine’s books.

Caine may also have given Stoker an indirect idea or two for Dracula. As Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s biographer, he had immortalized Rossetti’s exhumation of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, to retrieve a notebook of poems he had buried with her. Seven years after her death, Siddal was said to have been unnaturally well-preserved, much like the vampire Lucy Westenra. The Rossetti gravesite is located in Highgate Cemetery, near Hampstead Heath, and, while Stoker does not explicitly mention Highgate anywhere in his novel, it has nonetheless been commemorated in legend as the “Dracula cemetery.” Once a manicured park, Highgate is now a wildly atmospheric, managed woodland—a reincarnation that only intensfies its Gothic/ Romantic mystique.

Whatever his methods, inspirations, or editorial assistance, Stoker submitted the finished manuscript to his publisher, Archibald Constable, as The Un-Dead (his working notes indicate three possible titles—Count Dracula, The Un-Dead, and The Dead UnDead). At some point the title was changed to Dracula. It is not known whether this was at Stoker’s insistence or the publisher’s, but the decision was fortuitous—the one-word title itself, the three sinister syllables that crack and undulate on the tongue, ambiguously foreign but somehow alluring, would be an undeniable component of the book’s initial and continued mystique.

The house in Chelsea where Stoker completed his novel (Photos by the author)

The novel unfolds as a series of diaries and letters, imitating the epistolary technique introduced by Samuel Richardson in Pamela: or Virtue Rewarded (1740-1742), and later employed by Wilkie Collins as a narrative device for his groundbreaking detective novel, The Woman in White (1860). Jonathan Harker, a young English solicitor, travels to the wilds of Transylvania to conduct a real estate transaction for one Count Dracula, who desires to relocate to England. Harker’s firm has secured for the Count an abandoned estate called Carfax. But once received at Dracula’s castle, Harker finds the Count to be a creature of strange habits, and an even stranger appearance. In addition to pointed fingernails and hair on his palms,

His face was a strong—a very strong—aquiline, with high bridge of the thin nose and peculiarly arched nostrils; with lofty domed forehead, and hair growing scantily round the temples, but profusely elsewhere. His eyebrows were very massive, almost meeting over the nose, and with bushy hair that seemed to curl in its own profusion. The mouth, so far as I could see it under the heavy moustache, was fixed and rather cruel-looking, with peculiarly sharp white teeth; these protruded over the lips, whose remarkable ruddiness showed astonishing

vitality in a man of his years. For the rest, his ears were pale and at the top extremely pointed; the chin was broad and strong, and the cheeks firm though thin. The general effect was one of extraordinary pallor.

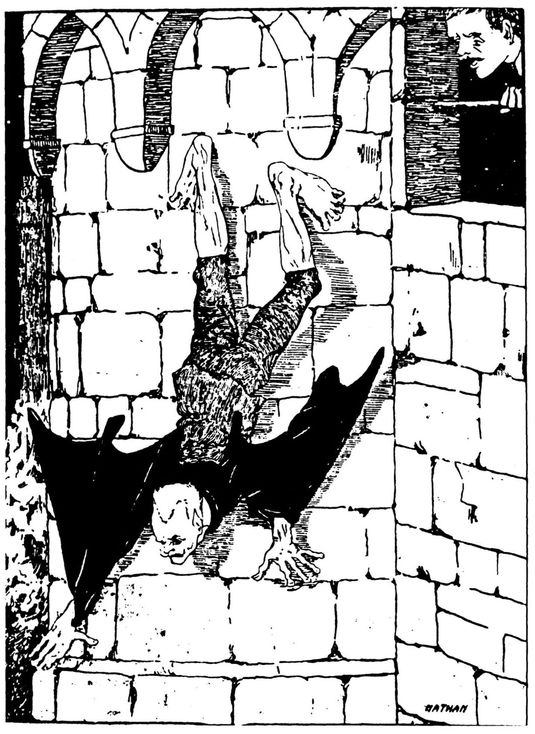

Dracula, Harker soons learns, is more parasite than host, a living-dead creature who sleeps in an earth-box by day and scales the walls of his castle like a monstrous winged lizard by night. Dracula intends to use the captive Harker to increase his knowledge of English, and then, upon his departure, abandon the young man to his trio of bloodthirsty wives, who have already made clear their ravenous interest.

The fair girl went on her knees, and bent over me, fairly gloating. There was a deliberate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive, and as she arched her neck she actually licked her lips like an animal, till I could see in the moonlight the moisture shining on the scarlet lips and the red tongue as it lapped the white sharp teeth. Lower and lower went her head as the lips went below the range of my mouth and chin and seemed about to fasten on my throat. Then she paused, and I could hear the churning sound of her tongue as it licked her teeth and lips, and could feel the hot breath on my neck. Then the skin of my throat began to tingle as one’s flesh does when the hand that is to tickle it approaches nearer—nearer. I could feel the soft, shivering touch of the lips on the supersensitive skin of my throat, and the hard dents of two sharp teeth, just touching and pausing there. I closed my eyes in a languorous ecstacy and waited—waited with beating heart.

Dracula interrupts the hungry foreplay, crying, “This man belongs to me!” and slakes his wives’ thirst with the blood of a peasant baby he has captured and brought home in a bag. When its pleading mother arrives at the castle gates, Dracula commands a pack of wolves to kill her. Harker attempts to kill Dracula with a spade as he rests in his coffin-box, but suffers a failure of will, managing only to mark the vampire’s forehead with a Cain-like scar. Dracula leaves for England with crates of the native burial earth necessary for his survival abroad, and Harker’s journal ends as he plans a dangerous escape from the castle.

The scene switches to England, where the story is taken up by the letters of Harker’s fiancée, Mina Murray, a “New Woman” of independent

mind and aspirations. Her best friend, Lucy Westenra, is of opposite temperament, an ideal of Victorian passivity. Soon after a derelict sailing ship drifts into Whitby Harbor during a storm, Lucy is taken by nightmares, sleepwalking, and anemia. Although cared for by a physician (Dr. Seward, who runs a local sanitarium adjacent to the Carfax estate) and despite a series of blood transfusions from her friends and fiance, Arthur Holmwood, she succumbs to the mysterious blood loss and dies. Harker, suffering from a severe brain fever, is returned to England, where he slowly recovers. Mina, however, falls prey to Lucy’s symptoms, including what she believes are visitations by the dead friend herself. As young children in the vicinity are molested by a “bloofer lady,”2 Dr. Seward consults with Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, a Dutch specialist in obscure diseases, who concludes that a vampire is at work. In a grisly scene, the vampire Lucy is chased to her tomb, where she is conclusively proven to be a vampire: “She seemed like a nightmare of Lucy as she lay there; the pointed teeth, the bloodstained, voluptuous mouth—which it made one shudder to see—the whole carnal and unspiritual appearance, seeming like a mockery of Lucy’s sweet purity.”

Van Helsing has the remedy, in the form of a three-foot-long wooden stake, which is delivered by Holmwood:

The Thing in the coffin writhed; and a hideous, blood-curdling screech came from the opened red lips. The body shook and quivered and twisted in wild contortions; the sharp white teeth champed together till the lips were cut, and the mouth was smeared with a crimson foam. But Arthur never faltered. He looked like a figure of Thor as his untrembling arm rose and fell, driving deeper and deeper the mercy-bearing stake, whilst the blood from the pierced heart welled and spurted up around it.

Harker regains strength and assists the others in the search for Dracula, who has made use of Renfield, an insect-eating lunatic in Seward’s care, to gain access to Mina. Under Dracula’s spell, Renfield’s appetites ominously mount the evolutionary scale. A vampire requires an invitation to a house, and Renfield happily supplies it, unable to resist Dracula’s offers of ever warmer degrees of blood:

“Rats, rats, rats! Hundreds, thousands, millions of them, and every one a life; and dogs to eat them, and cats too. All lives! All red blood …”

But when Renfield’s usefulness is over, Dracula kills him. Several of the Count’s earth-boxes are located and destroyed, but the vampire safeguards one and flees back to the continent. A suspenseful chase back to Transylvania ensues, Dracula is destroyed just short of reaching his lair, and Mina is released from her thrall.

Dracula is a radically different book at the turn of the twenty-first century than it was in 1897; though the text has not been altered, its context has been transformed—and transformed substantially. Attempts to make sense of its author’s intentions are particularly difficult since the notes and manuscript are unaccompanied by journals, diaries, or letters that might reveal Stoker’s state of mind, and there is a relative dearth of biographical information.3 In all likelihood he considered the book no more than an entertainment, a page-turning thriller. Stoker’s serious critics are virtually unanimous in their conclusion that Dracula was in part the product of unconscious influences, and not a totally controlled work. Stoker’s voluminous correspondence on behalf of Henry Irving (he said that he wrote as many as fifty letters a day, and as many as half a million during the twenty-six years of his employment) as well as his own prolific fictional output suggests that he could produce prose with a facility approaching automatic writing.

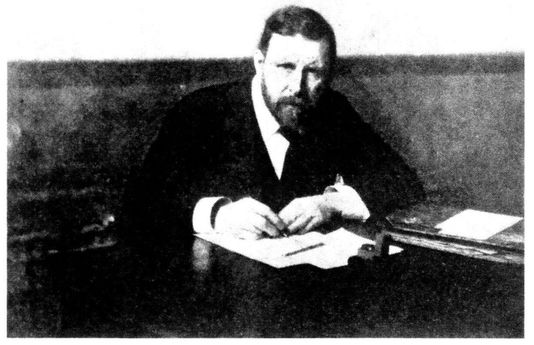

A rare photo of Stoker at work, from a 1904 issue of Harper’s Weekly (Author’s collection)

The interpretive conundrums thus raised are nearly overwhelming. If Stoker didn’t intend a larger meaning, can such a meaning be legitimately imposed? Dracula has, for instance, come to be regarded in many quarters as a tantalizing Rosetta Stone of the darker aspects of the Victorian psyche, and, indeed, serves the function admirably, as hundreds of scholarly articles and studies will attest. But Dracula can also be read fruitfully as a Christian allegory (or parody), as a parable of cultural xenophobia, as an occult text, or as a thinly veiled Darwinian or even Marxist tract. The inescapable conclusion is that Bram Stoker, working in a largely intuitive manner, but no doubt propelled by more than a few personal demons, managed to tap a well of archetypal motifs so deep and persistent that they can assume the shape of almost any critical container.

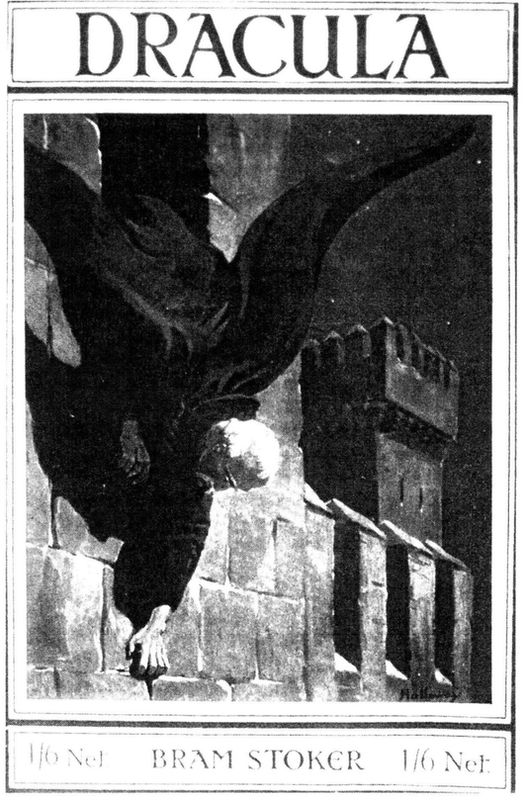

Dracula was published by Constable on May 26, 1897, with no literary theorists in sight. Stoker had already arranged a marathon staged reading of the book at the Lyceum on the morning of May 18,

ostensibly to protect his interest in a dramatic copyright.4 Such readings were common in Stoker’s time, but their value in preventing the stage piracy of literary works was not universally acknowledged. The Stage, for instance, called them “absurd ‘productions’ given for the purpose of securing stage rights,” and urged some “bold, bad man” to challenge the practice with an unlicensed adaptation. “Then managers and authors will see the wisdom of going about the matter of ‘production in accordance with the law’ in a more sensible manner.”

In any event, the Lyceum briefly became Stoker’s own macabre toy theatre, though the brevity may well have felt like an eternity. The reading was stupefyingly long—five acts and forty-seven scenes, lasting more than five hours. Barbara Belford states (intriguingly, but without documentation) that Stoker hung the stage with settings for Irving’s Macbeth, a production then in storage. Lyceum records show that the standing sets on May 18, 1897, were for Victorien Sardou and Emile Moreau’s comedy Madame Sans-Gênes, in which the imposing Henry Irving played a diminutive Napoleon, aided by oversized furniture and other perspective tricks to diminish his height.

The task of being the first actor to impersonate Dracula on stage fell to a “Mr. Jones,” who, according to the best evidence, was T. Arthur Jones, a supporting member of the Lyceum company. Edith Craig, the daughter of Henry Irving’s leading lady Ellen Terry, read the role of Mina. The parts of Jonathan Harker and Abraham Van Helsing were interpreted by Herbert Passmore and Tom Reynolds. Eleven other actors took part, mostly from the ranks of salaried Lyceum players, but a few were completely unknown, perhaps just friends of the author.

The “script” Stoker later submitted to the Lord Chamberlain (the office that approved and licensed all stage productions in England) was an elaborate cut-and-paste of printer’s galleys, heavily emended in holograph by Stoker. As a stage play, it is simultaneously ludicrous

and oddly (if incompetently) earnest. In reconceiving his book for the stage, Stoker faced the same obstacles that would frustrate later adaptors; the novel’s geographical sweep and scope, coupled with its wordy, epistolary format pose distinct problems for the theatre. For instance, to set the scene outside Dracula’s castle, Stoker is forced to give Jonathan Harker a breathless opening speech that is almost a parody of melodramatic exposition:

HARKER Hi! Hi! Where are you off to! Gone already! (knocks at door) Well, this is a pretty nice state of things! After a drive through solid darkness with an unknown man whose face I have not seen and who has in his hand the strength of twenty men and who can drive back a pack of wolves by holding up his hand; who visits mysterious blue flames and who wouldn’t speak a word that he could help, to be left here in the dark before a—a ruin. Upon my life I’m beginning my professional experience in a romantic way!

Any hopes Stoker may have had to impress his employer with dramaturgical skill came to naught in a scene recounted by his biographer and great-nephew, Daniel Farson: “Legend has it that Sir Henry entered the theatre during the reading and listened for a few moments with a warning glint of amusement. ‘What do you think of it?’ someone asked him unwisely, as he left for his dressing room. ‘Dreadful!’ came the devastating reply, projected with such resonance that it filled the theatre.”

The idea that Stoker created Dracula with Henry Irving in mind—either as a potential Irving stage role, or, more darkly, as a resentful, revengeful caricature of a domineering, life-draining employer, a la Polidori and Byron—has become such a deeply ingrained part of the Dracula legend that it is often difficult to separate hard fact from reasonable assumption from totally unsupportable speculation. The image of Stoker as Jonathan Harker, locked up in the Lyceum “castle,” forced to do the bidding of a boss literally from hell, makes for a good story and a glib, if irresistible sound bite.

But is it true?

Evidence bolsters the notion that Stoker at some point envisioned Irving as Dracula onstage, and openly talked about it, at least after the book’s publication. According to Chicago drama critic Frederick Donaghey, who made the writer’s acquaintance during one of Ir-ving’s

turn-of-the-century tours, “When the late Bram Stoker told me that he had put in endless hours in trying to persuade Henry Irving to have had a play made from Dracula and to act in it, he added that he had nothing in mind save the box office. ‘If,’ he explained, ‘I am able to afford to have my name on the book, the Governor [as Irving was familiarly known] certainly can afford, with business bad, to have his name on the play. But he laughs whenever I talk about it; and then we have to go out and raise money to put on something in which the public has no interest.’”

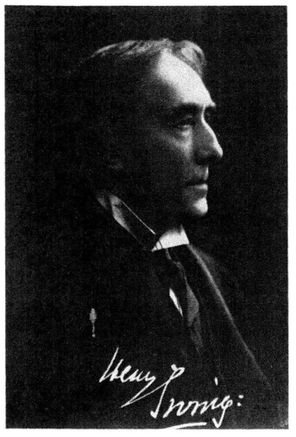

The boss from hell? Stoker’s employer Henry Irving is often described as a direct inspiration for the character of Dracula, though the truth may be more complicated. (Author’s collection)

Stoker went on to tell Donaghey his conception of Irving as the king of vampires: “The Governor as Dracula would be the Governor in a composite of so many of the parts in which he has been liked—Matthias in The Bells, Shylock, Mephistopheles, Peter the Great, the bad fellow in The Lyons Mail, Louis XI, and ever so many others, including Iachimo in Cymbeline. But he just laughs at me!”

Stoker was correct in anticipating the theatrical possibilities of his story, though they would not be realized in his lifetime. But documented evidence that Irving himself was the primary inspiration for

the vampire is essentially nonexistent—decades of critical and biographical assertions to the contrary.

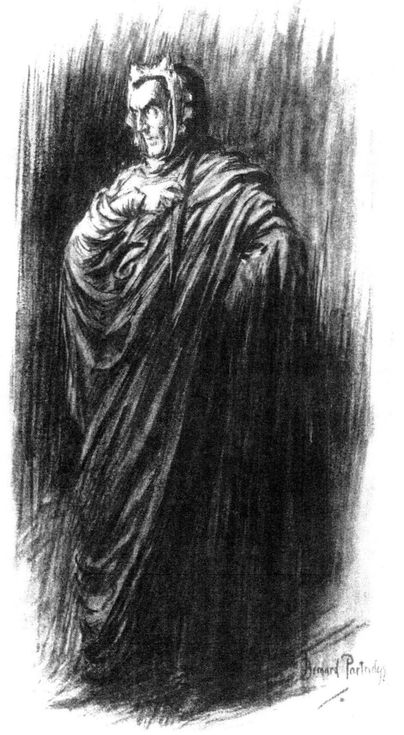

As interpreted by the artist Sir Bernard Partridge, Henry Irving’s Mephistopheles strikes a Dracula-like pose. (Courtesy of the Board of Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum)

However, Stoker certainly had reason to believe Irving might be interested in another supernatural role, and, perhaps, involve him in the process. In 1878, Irving had enlisted Stoker to help revise the problematic text of Vanderdecken, based on the Flying Dutchman legend. Despite the deficiencies of the script, Irving played the part memorably, with eyes that “really seemed to shine like cinders of glowing red from out the marble face”—the identical gaze cast by Count Dracula, the living-dead captain of another phantom ship. Stoker also described Irving’s “ghastly pallor,” his eyes shining with “the wild glamour of the lost—in his every tone and action there is the stamp of death. Herein lies the terror—we can call it by no other name—of the play. The chief actor is not quick but dead.” Or, in a word that Stoker was to coin and make immortal for a public far less rarified than that of the Lyceum, “un-dead.”

“I believed in the subject,” wrote Stoker of the Dutchman legend, “and always wanted [Irving] to try it again—the play, of course, being tinkered into something like good shape, or a new play altogether written.” Instead of enlisting Stoker’s direct creative input, Irving proposed the project to Hall Caine. According to Stoker, “Irving had a great opinion of Caine’s imagination and always said he would write a great work of weirdness some day.” As Caine wrote, “During many years I spent time and energy and some imagination in an effort to fit Irving with a part … I remember that most of our subjects dealt with the supernatural, and that the Wandering Jew, the Flying Dutchman and the Demon Lover were themes around which our imagination constantly revolved.”

Caine instead proposed an alternate, but closely related subject. In 1895 he had published a narrative poem called “Graih my Chree” (Manx for “Love of My Heart,” though the poem itself was written in English). It was a variation on the traditional Scottish ballad “The Demon Lover” about a woman seduced into leaving her husband by a returned, long-lost suitor—only to learn, far too late, that he is a cloven-hoofed demon, and their heavenly shipboard honeymoon is actually bound for hell. Irving rejected Caine’s scenario, on the grounds that he was too old to be convincing as the supernatural seducer, and asked Caine to return to the safer, more age-appropriate

ancient-mariner theme of the Dutchman. Caine tried, but Irving proved an impossible collaborator. Caine’s conception of the Dutchman was either too unsympathetic, too brutal, too young, or too tall—whatever. The project was finally dropped. “[I] n spite of the utmost sincerity on all sides [including Stoker] our efforts came to nothing, and I think this result was perhaps due to something more serious than the limitation of my own powers. The truth is that, great actor as Irving was, the dominating element of his personality was for many years a hampering difficulty … .”

Given all this, is it possible that Irving was even approachable to play Dracula?

Despite Stoker’s press puffery in Chicago, Dracula as presented in the novel shares almost nothing with the stage characters Stoker enumerated, besides the frequent trappings of aristocracy. According to first-hand accounts, Irving’s interpretation of Shylock was revolutionarily nuanced, changing forever anti-Semitic stereotypes Stoker nonetheless imputed to the Count (a hook-nosed offense to Christianity who hoards gold, kills babies for their blood, and so on). Irving’s Mephistopheles was said to be both intellectual and ironic. Beyond the novelty of his supernatural parasitism, Dracula, as the character Stoker penned, is a monomaniacal bore. Irving’s Matthias in The Bells and Louis VIII were unsympathetic characters nonetheless given theatrical dimension by their terror of persecution. Dracula is persecuted, but never, even at the moment of his death, does he seem the least bit terrified. Not once does Stoker give his vampire a theatrical moment of fear or contrition. The bad twin in the The Lyons Mail is certainly a villain (half of a showy dual role), but hardly a vampire. Iachimo in Cymbeline is an Iago-like schemer who sows suspicions of infidelity, but, unlike Iago, confesses and is forgiven. For Dracula, there is no redemption, no dramatic reversal, no irony, no charisma.

In short—no applause.

Dracula never approaches Irving’s basic requirements for a stage role, and, unless we regard Stoker as a delusional sycophant, it may be worth considering that his account to the Chicago reporter might have been nothing more than a bit of poker-faced blarney. For, as Frederick Donaghey also noted, “He had written, in ‘Dracula,’ a ‘shilling shocker,’ however successful a one, and was frank about it.”

The Irving legend persists, in part, because Dracula itself is so permeated with trappings of the stage. Dracula is the monarch of vampires, just as Irving was the king of the theatre. Imagistic references to Macbeth, Irving’s favorite role, recur throughout the novel (a cursed warrior-king in a desolate castle, three weird sisters, somnambulism, blood imagery, etc.) and other Shakespearean allusions abound. A supernatural shipwreck, coupled with a magus who drives the elements and has an animalized slave at his disposal all seem dark reflections of The Tempest. Images of Irving as a cloaked Mephistopheles seem positively Dracula-like to the modern viewer—until one realizes that Stoker’s Dracula never wears a cloak except for one brief wall-crawl. For the rest of the book, he is a cadaverous, puritanical figure clothed in black. By contrast, Irving’s Mephistopheles was a flamboyant peacock; black-and-white reproductions of his costume fail to convey the full impact of his brilliant red raiment. Dracula sinks into the shadows. Mephistopheles grabs the spotlight.

At the time of Dracula’s publication, not a single reviewer drew a parallel between Irving and Dracula. There was, however, considerable vampire gossip about another theatrical luminary, the actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell, the apparent model for Philip Burne-Jones’s scandalous painting “The Vampire,” first exhibited in London within weeks of Dracula’s publication.5 Burne-Jones’s canvas depicted a moonlit bedroom wherein a crouching female figure, teeth bared, gloats over a prostrate male, whose life has been drained away through a wound over his heart. The painting was accompanied by the now legendary verses penned by the artist’s cousin, Rudyard Kipling:

A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair

(We called her the woman who did not care)

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair

(We called her the woman who did not care)

The actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell as depicted by painter Philip Burne-Jones in his fin de siècle scandal, The Vampire (1897); a 1902 souvenir reproduction (Author’s collection)

But the fool he called her his lady fair—

(Even as you and I!)

(Even as you and I!)

Commentators have focused so relentlessly on Irving’s influence on Dracula that they may have missed a more obvious theatrical model: Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Svengali in the 1895 stage adaptation of George du Maurier’s Trilby, published as a novel to an astonishing public reception the previous year. Profusely illustrated by the author himself, Trilby is widely regarded as the best-selling novel of its time. Svengali is a malignant mesmerist who transforms a pliable artist’s model (Trilby) into a superstar of the musical stage. Unfortunately, the hypnotic process drains and kills her. Du Maurier describes Svengali as an “incubus,” and in one memorable illustration depicts him as half-human and half-spider—just as Stoker would present Dracula as a creepy amalgam of man, lizard, and bat. In his human form, Svengali provides a much closer physical model for Dracula than any of Irving’s characterizations. He has the profile of a predatory bird, not to mention pointed ears. Svengali sports a beard, a style Dracula also adopts, at least for a couple of scenes.

As an actor-manager, Tree was Irving’s closest rival, and, when it was announced that Tree had acquired the stage rights to Trilby, The Stage lamented that Henry Irving had not struck first. Trilby was a theatrical goldmine, enabling Tree to build Her Majesty’s (later His Majesty’s) Theatre, and eventually to found the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. It is unreasonable to assume that Stoker wasn’t keenly aware of Tree’s greatest success, especially because it revolved around the theme of mesmerism, which greatly interested him.

The wild theories of “animal magnetism” popularized in the previous century by Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815) were updated and given a veneer of scientific respectability by Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-93), a renowned French physician whose lectures included sensational demonstrations of hypnosis, hysteria, and somnambulism. Freud was one of his pupils. Stoker mentions Charcot’s death in Dracula; his Irving memoir makes note that the doctor was one of the Lyceum’s many illustrious guests. Stoker himself once gave a Charcot-like “lecture” on hypnotism during one of the Lyceum’s transatlantic crossings, though the event appears to have been little

more than a joke, involving a “hypnotized” confederate recruited from Irving’s stable of actors.

The revived interest in hypnosis (a term coined in 1852) overlapped with the spiritualist craze that swept Europe and America in the late nineteenth century, saturated with ritualistic protocols of trance and mediumship. The “experiments” of spiritualism rose, in part, to provide some quasi-scientific justification for the traditional Christian concept of an afterlife, under mortal siege by rapid advances in science and an ever-encroaching materialism. The trappings of spiritualism are discernible in Dracula; since the Count is dead, the hypnotic trances of Lucy and Mina are, ipso facto, mediumistic. Like spiritualism, Dracula himself emerges as a kind of fantastic bargained compromise between science and religion, however hellish and grotesque—Darwin dancing with Dante, as it were. The afterlife might be a bloody jungle, but at least there was still some kind of afterlife.

Fear of losing rank on the evolutionary scale obsessed privileged Victorian men in an age when Britain’s primacy on the world stage was faltering; women were seeking unprecedented political, economic, and sexual emancipation; and foreigners were appearing on English shores in unprecedented numbers. Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection took on a dark cultural immediacy.

Darwin never posited notions of progress, privilege, or politics, but his theories (reduced, in their crudest form, to the politically expedient notion of “the survival of the fittest”) were widely pounced upon as validation for all manner of social imbalances. The neomesmerists, for instance, maintained that only the fittest could resist hypnotic influence. In Dracula, one of the vampire’s most vulnerable victims is Renfield, a weak-minded maniac whose bizarre mental disorder (“zoophagia,” i.e., the human compulsion to devour ever-more-evolved lower animals) is a neat Darwinian metaphor, albeit one totally concocted by Stoker. In the best Henry Irving manner, Renfield gnaws the scenery of the greatest intellectual drama of his time. His madness is associated with his capitulation to godless science. “I want no souls. Life is all I want,” Renfield declares. As Clive Leatherdale, one of Dracula’s leading scholars, has noted, “Dracula, of course, is an active materialist, for whom all phenomena are sim-ply

examples of matter in motion. Like all vampires, Dracula is shorn of a soul, physical existence being all that concerns him. Stoker self-evidently does believe in souls, and his novel takes the form of a protest—however veiled—against the blasphemies of Darwin … .”

George du Maurier’s Svengali orchestrates evil in Trilby (1894). (Author’s collection)

Darwin himself was blasphemed in the supremely cranky tract Degeneration (published in Germany as Enartung in 1892, translated into English in 1895), written by the Austrian physician Max Nordau

(1849-1923). Degeneration was a hot-button bestseller of its time. Nordau’s goal was nothing less than the medicalization of art and literature along pseudo-Darwinian lines. Degeneration sounded the alarm with classic fin-de-siècle pessimism. “Things as they are totter and plunge,” Nordau wrote. “Views that have hitherto governed minds are dead or driven hence like dethroned kings … .” Sure signs of degeneration could be found in physiognomy; atavistic irregularities of the ears, teeth, and fingers were dead (or, as employed by Stoker, un-dead) giveaways, and a good indication of criminality. But, Nordau cautioned, “Degenerates are not always criminals … they are often authors and artists. These, however, manifest the same mental characteristics, and for the most part the same somatic features as assassins and anarchists.” Nordau excoriated Walt Whitman, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Emile Zola, Oscar Wilde, and many others for their alleged crimes against human progress. Stoker mentions Nordau by name in Dracula, but his interest in physiognomy preceded Nordau’s book by over twenty years. In his 1872 letter (ironic, in retrospect) to Whitman, Stoker wrote, “You are I know a keen physiognymist. I am a believer of the science myself and am in a humble way a practicer of it.”

First-time readers of Dracula, or readers who return to the novel after many years, are often surprised at what a repellent, unattractive character the Count truly is, more literal wolf than literary Lothario. Stoker broke sharply with the Byronic tradition in his delineation of Dracula as a cadaverous ancient with bad breath and hairy palms. Stoker’s first description of Dracula (aquiline profile, bushy hair, massive eyebrows that meet over the nose, the pointed ears, etc.) is an almost verbatim reiteration of characteristics that could be found in the influential criminology texts of Cesare Lombroso (1836-1909), Nordau’s esteemed protégé, to whom Degeneration is dedicated, and whose name also appears in Dracula. Where Nordau’s guidelines about the physical appearance of a devolved villain were rather general, Lombroso’s detailed description of a “typical” criminal degenerate gave Stoker a perfect, paint-by-numbers portrait.

Physical stereotyping often followed lines of class and ethnicity, and begat bigotry. According to cultural historian Bram Dijkstra, “Dracula may not officially have been one of those horrid inbred

Jews everyone was worrying about at the time Stoker wrote his novel, but he came close, for he was very emphatically Eastern European … like du Maurier’s ‘filthy black Hebrew,’ Svengali.” Stoker’s physical creation goes beyond racist notions of degeneracy into the animal/human fantasies of classical mythology: Count Dracula, with his satyr ears and animal appetites, is a vivid evocation of the phallic goat-god Pan, the nightmare demon of antiquity.

Max Nordau, author of Degeneration (Author’s collection)