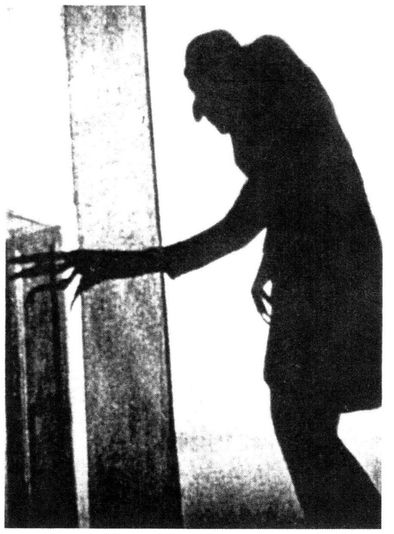

Production designer Albin Grau created a frightening publicity portrait of Max Schreck in Nosferatu (1922). (Author’s collection)

THE ENGLISH WIDOW AND THE GERMAN COUNT

In which the book is stolen, and made a rude spectacle of

by Germans, who are not forgiven, and who are hounded

into ruin by Florence and a pack of solicitors.

by Germans, who are not forgiven, and who are hounded

into ruin by Florence and a pack of solicitors.

ON APRIL 27, 1922, G. HERBERT THRING DRAFTED A LETTER SIMILAR TO many he wrote as secretary of the British Incorporated Society of Authors. He had no idea of the convoluted affair that would arise from this particular missive, nor of the extraordinary intensity and determination of the person to whom it was addressed. “In accordance with my promise to you over the phone today, I am now sending you the papers of the Society. If, after perusal, you would like to join, would you kindly fill up and return the election form in order that your name may go before the Committee of Management at their next meeting, which will take place Monday next. The subscription, as you will see by the prospectus, is £1.10.0 a year.

“As I mentioned to you, we have many literary executors members of the Society, and if you are in need of help in regard to your husband’s literary work, no doubt you will let me know when returning the election form.”

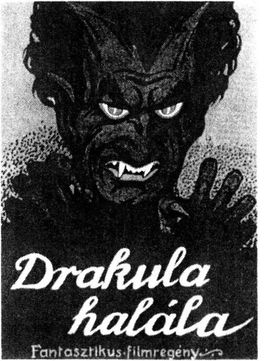

The letter’s recipient, Mrs. Bram Stoker of William Street, Knightsbridge, returned the form with a cheque. Formalities dispensed with, she now left no doubt whatsoever about the kind of help she needed. Included with her letters were printed documents that had been sent to her from Berlin—the program of a cinematographic event that had taken place the previous month at the Marble Hall of the Berlin Zoological Gardens, accompanied by advertisement drawings of one of the most grotesque creatures Thring had ever seen: a hideous face, more verminous than human, with a bald bulging cranium, pointed ears, and hooked nose. From the cruel slash of a mouth sprouted two ratlike fangs. Whatever this monstrosity was, the Berlin Zoo was certainly the appropriate environment for it!

Thring read on, learning that the event in question was a German film adapation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula—“freely adapted” according to the program, a point angrily confirmed by Stoker’s widow, who had neither given permission nor received payment for Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens. The “Symphony of Horror” seemed to be a rather elaborate, if relentlessly morbid affair, the first venture of a company called Prana-Film. The screening had been quite lavish, with full orchestral accompaniment and generous coverage in the cinema press. Money was obviously being thrown around over this thing.

Florence Stoker was justifiably upset. Since her husband’s death her financial situation had become increasingly precarious. She could depend to a certain extent upon her son, Noel, now an accountant, but their relationship had always been rather distant. Most of her husband’s books had gone out of print, without much hope for reprints and royalties. Only Dracula provided a steady, if skimpy and unpredictable, income (the French rights, for example, had brought only 350 francs in 1920). Publishing then was a prudent, conservative business—today’s extravagant, speculative advances were unheard of and Dracula was a steady backlist title, not a grand best-seller. Still, there had been several editions, from Constable and now Rider. She owned a certain number of paintings, with which she would never part—they were the last memories of those distant days

on Cheyne Walk, where the Stokers’ lives had been entwined with the likes of Sargent, Whistler, and the Pre-Raphaelites. With the death of Henry Irving, the Stokers’ connection to such glittering circles had grown tenuous, and after Stoker’s death Florence found herself in the same penniless circumstances that had prevented her marriage to Oscar Wilde. Wilde was dead. Her husband was dead. So were Irving, the Lyceum, the age. Was it possible that all that survived of her life was Dracula? Once, she remembered, she had attended the premiere of Lady Windermere’s Fan, and had still drawn Wilde’s eye with “a wonderful evening wrap of striped brocade.” Now she warmed herself by pawning the threadbare cloak of a moldering vampire—when takers could be found.

And in Germany, they were trying to steal this as well.

She was old, but still quite handsome, and though her own eyesight was failing badly, others could see very well the warrior-saint profile that had pleased Burne-Jones. At the age of sixty-four she was being called upon to live up to the faded image.

The makers of Nosferatu had no idea of the fierce adversary they were to have in Florence Stoker, and probably didn’t even know that she existed. A general air of impracticality seems to have surrounded almost everything connected with Prana-Film and Nosferatu.

Prana-Film (the name derived from the Buddhist concept of prana, or breath-as-life) was founded in January 1921 on a capitalization of twenty thousand marks, under the codirectorship of businessman Enrico Dieckmann and the designer/painter/architect Albin Grau. An ambitious prospectus of potential projects was unveiled, revealing a distinct predilection for the occult, the Romantic, and the bizarre. The films were to be produced according to “new principles.” In addition to Nosferatu, projects mentioned included such evocative titles as Hollenträume (Dreams of Hell) and Der Sumpfteufel (The Devil of the Swamp). Only Nosferatu would be realized—Prana’s first and last gasp.

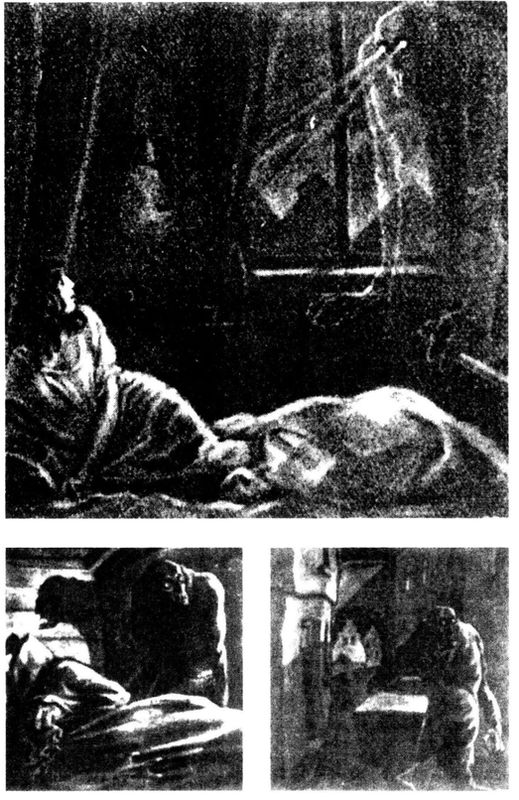

Grau was an “ardent spiritualist” with no apparent experience in motion picture production. He was also an active member of the secret society Ordo Templi Orientis, an offshoot of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, headed for many years during Grau’s involvement by the legendary satanist Aleister Crowley. Dieckmann’s credentials are sketchy, but both men understood Dracula’s powerful potential as cinema. One of Grau’s drawings for Nosferatu, reproduced

here, almost explicitly evokes film itself as demonic magic. Standing over a woman’s bed, the vampire illuminates his intended prey with beams of light projected from his eyes. The penetrating effect was not, unfortunately, used in the film.

The word nosferatu was taken from Stoker, who found it in Emily Gerard’s essay “Transylvanian Superstitions” as a Romanian word for vampire. Largely because of the German film’s subsequent worldwide fame, the word has been solemnly canonized as an authoritative term in folklore.

But in fact, “Nosferatu” does not exist in the Romanian language, or any other language. The Romanian word for vampire is vampir. Emily Gerard was not a native speaker, and seems to have misread or mistranscribed another Romanian word—perhaps the adjective nesuferit , meaning “insufferable” or “plaguesome.” In Stoker’s novel, the word is used generically, but the makers of Nosferatu gave it the status of a capitalized, proper name.

Several other theories of the etymology of nosferatu have been put forth, none very convincingly. Among them are the Greek word nosophoros , meaning “plague bearer,” and the Romanian necuratul, meaning “devil.” Outside of Gerard’s essay and subsequent book, the word seems to only have appeared in the writing of one other folklorist, Heinrich von Wlislocki (1856–1907), who shortens it to “Nosferat.” But Wlislocki quite possibly relied on Gerard, who published first; some passages in their writing are very similar. Gerard: “The living vampire is in general the illegitimate offspring of two illegitimate persons.” Wlislocki: “The Nosferat is the still-born, illegitimate child of two people who are similarly illegitimate.” Otherwise, the word nosferatu is found in no Romanian, Hungarian, or Eastern European dictionaries, nor in any standard folklore works available to Gerard as a synonym for “vampire” or anything else. (It conceivably could have been a localism, but no convincing documentation has surfaced.) Additionally, the oft-repeated contention that nosferatu is a Romanian word meaning “not dead” is without basis in lexicography.8

The oddness of its title aside, Nosferatu would come to be legitimately canonized as a key work of expressionist cinema. The arts in Germany after the war were deep in the ferment of expressionism—a highly imprecise, but useful term, much like “postmodernism” today. Expressionism was a category sufficiently elastic to include “every kind of cultural commitment or posture of the first quarter of the twentieth century.” In theatre, film, and visual arts, it generally included distortion, exaggeration, and extreme metaphor. Images invariably represented inner landscapes, with an overriding emphasis on composition and shadow play. Expressionist filmmakers naturally gravitated toward the fantastic and occult, where many of these elements could be found ready-made, or begging to be shaped. Notable expressionist films and themes prior to Nosferatu included The Golem (1914, remade 1920) and Homunculus (1916), both dealing with the plight of artificially created beings; The Student of Prague (1913, remade 1926), spotlighting the doppelganger legend, by way of Edgar Allan Poe; and, of course, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), where somnambulism, murder, and madness play against some of the most deliriously off-Uter sets of all time. The films all have their distinct personalities, and draw eclectically from the materials of expressionism; Caligari, for instance, has been criticized for an overreliance on painted theatrical effects while ignoring the expressive possibilities of the camera. Nosferatu, conversely, would draw criticism—and praise—for its use of natural, rather than contrived settings. And Paul Wegener, director of both versions of The Golem, denied any expressionist intentions at all. A major characteristic of the filmmakers of this period was an individualism that transcended labels and categories.

A symphony of horror and a rainbow of rats: one of Albin Grau’s many striking advertisements (Author’s collection)

As director for their premiere venture, Grau and Dieckmann engaged the thirty-two-year-old Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, whose distinctly original vision would later earn him a place in the pantheon of world cinema, on the basis of such influential works as The Last Laugh (1924), Faust (1926), and Sunrise (1927). Murnau had worked with the legendary theatrical producer Max Reinhardt before the war and no doubt was influenced by Reinhardt’s pictorial aesthetic of light, shadow, and spectacle. Murnau would soon pioneer the use of the mobile camera, and eventually create the cinematic equivalent of Reinhardt’s theatre.

Another Reinhardt alumnus who contributed to Nosferatu was screenwriter Henrik Galeen, who, faced with adapting a lengthy, rather wordy Victorian novel as a silent film, deftly excised everything except the visual, metaphorical, and mythic. He changed all the characters’ names—Count Dracula became Graf Orlok, Harker was now Hutter, Mina was called Ellen, Van Helsing renamed Bulwer, etc.—and simplified the plot while retaining the basic structure: the young man’s journey to Transylvania to sell a house to a vampire, the creature’s sea voyage to the young man’s town and subsequent

possession of his wife, and the intervention of a patriarchal scientist to reveal the vampire pestilence.

Murnau’s copy of the shooting script, now in the possession of the Cinémathèque Française, shows that Galeen worked in an impressionistic, rhetorical style, suggesting rather than dictating the finished product (“A rope is dangling from the deck. Is it swaying in the wind?”). Since much of Nosferatu considerably deviates even from Murnau’s personally annotated script, it is apparent that a good degree of improvisation occurred during the filming.

Murnau shot Nosferatu on location in the summer of 1921, with Fritz Arno Wagner as cameraman. Location shooting was a novel idea at the time, and, in the case of Nosferatu, most likely a response to a limited budget. Thus, the heightened artificial settings so typical of expressionist films are absent, the director and photographer resorting instead to carefully plotted visual compositions, with the camera immobile. Night scenes were shot in broad daylight, then tinted deep blue for release. Most prints in circulation today lack this key effect, and are in effect stripped-down skeletons of the original, which, for its premiere, also had a live orchestral score by Hans Erdmann.

Nosferatu opens with Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) taking leave of his wife Ellen (Greta Schroeder-Matray) at the behest of his strange employer, Knock (Alexander Granach). Knock, here the Renfield character, directs Hutter to travel to the castle of Graf Orlok; the mysterious nobleman wishes to buy a deserted house adjacent to Hutter’s. Hutter travels by coach to Orlok’s castle, stopping for one night at a gypsy inn where he reads a book of vampire superstitions. The next day he is driven to a bridge the gypsy drivers refuse to cross. Hutter traverses it by foot, and, having entered the land of phantoms by his own volition, is met by a coach that moves with a jerking, accelerated energy (a stop-motion effect meant to be frightening but which finally appears only comical). A muffled coachman with penetrating eyes directs Hutter into the coach, which returns the way it came, and this time the landscape of phantoms is projected in negative, another special effect that sounds more intriguing than it actually looks. It should be remembered, however, that Murnau and his crew were working with extremely limited technical resources.

At the castle, Hutter is greeted by Graf Orlok, a strange, secretive spectre of a man who becomes unaccountably excited at the sight of Hutter’s blood when he accidentally cuts himself. He also admires a portrait of Ellen the young husband carries with him: “What a lovely throat!” he exclaims. Late that night, Hutter opens the door of his room, and is horrified to see Orlok approaching, his features exaggerated and hideous, a vampire as described in the gypsy book. Hutter hides in bed but the vampire enters the room and attacks him. Ellen, at home in the town of Wisborg, cries out her husband’s name as she sleeps. The vampire, disturbed by the psychic warning, withdraws from the young man’s bedchamber.

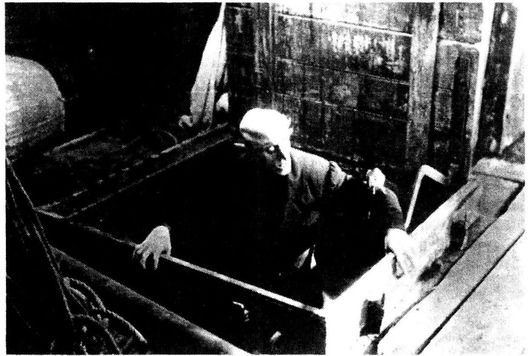

The next day, shaken by the vampire’s midnight visit, Hutter discovers a rotting coffin in which Orlok is resting. He flees the crypt and watches helplessly as the awakened monster loads a wagon with coffin-boxes and departs for Hutter’s town.

Murnau then crosscuts several sequences, including Hutter’s escape, hospitalization, and recovery; Knock’s madness and confinement to an asylum; and Professor Bulwer’s experiments with carnivorous plants and other devouring organisms. Aboard the sailing ship carrying his earth-boxes, Orlok is now completely transformed into Nosferatu, even his fingers swollen into malignant, predatory hooks. One by one he stalks and kills the crew.

The derelict vessel glides into the Wisborg harbor, Nosferatu’s arrival coinciding with the onset of plague. Hutter’s wife, Ellen, reads the book about vampires he has brought with him from the land of phantoms; she learns that the vampire can be defeated only if a virtuous woman willingly lets him remain with her until dawn. Nosferatu, who has been watching her from his house across the street, gladly presents himself when she throws open her window. He fixes himself at her throat like a motionless leech, and never notices the onset of daybreak until it is too late. The sunlight reduces Nosferatu to a puff of smoke. Ellen dies as well, sacrificing herself to banish the plague and to restore a balance of nature.

The central, striking image of Nosferatu will forever and always be the cadaverous Max Schreck as the vampire, his appearance totally unlike most film vampires that would follow. Schreck’s characterization of Dracula as a kind of human vermin draws its energy in part

from Stoker, but also from universal fears and collective obsessions. (How else is it possible for one character to be interpreted—as it has been—as “a Shylock of the Carpathians” as well as a cinematic anticipation of Hitler? Ugliness, it seems, is in the mind of the beholder.) The inspired makeup was probably also Albin Grau’s invention, building up the actor’s features with putty, creating batlike ears and ratlike teeth, and gradually elongating the actor’s fingers during the course of the film (John Barrymore had used the same kind of finger effect in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, though not quite so hideously). With his padded costume and stiff, halting gait, Schreck is more a filmic precursor of Frankenstein’s monster than the elegant, evening-clothed blutsaugers who were to come. Schreck—the name means “terror” in German—was the actor’s actual name, and not merely a pseudonym, as has been repeatedly suggested. Born in 1879 in Berlin, Schreck was also a former Reinhardt company member and went on to play character roles in German films until the time of his death in 1936. None, of course, achieved the transcendent fame of Nosferatu.

Despite its technical limitations (one can only wonder at what Murnau could have achieved with the full studio resources later at his disposal for Faust or Sunrise), Nosferatu remains an impressive film. Its Dracula is genuinely, viscerally frightening. Conscious poetry and metaphor are everywhere, to a degree Stoker only hints at, or stumbles upon. In one famous scene aboard the doomed ship, the vampire springs from his rat-filled coffin like an obscene jack-in-the-box, an image simultaneously suggesting erection, pestilence, and death. In an influential essay, the French critic Roger Dadoun calls the character of Nosferatu “a walking phallus or ‘phallambulist.’” Nosferatu’s rigidity is that of a corpse, “but the signs of an aggressive sexuality are abundant and spectacular … Nosferatu might be called The Pointed One, bearing in mind all the simple and basic symbolism attached to pointedness. His face is pointed, so are his ears, his shoulders, his knees, his back and of course his nails and fangs. According to a primitive mental operation which prefers not to distinguish the structure of the parts from that of the whole, Nosferatu is an agglomeration of points.”

The more recent critics of Nosferatu have made much of Murnau’s widely acknowledged homosexuality as being germane to the film; one much-quoted lecture-essay by the experimental filmmaker Stan

Brakhage goes so far as to characterize Nosferatu as a deliberate exercise in camp. (After reading Brakhage, one is almost disappointed when Max Schreck fails to appear in garter belt and mascara.) While Stoker’s novel is built on a complicated psychological foundation of sexual ambiguity, Nosferatu is starkly devoid of the consciously ambiguous or knowingly ironic. Modern culture and its complexities are banished; in sharp contrast to Dracula—a very up-to-date book for its time—Murnau’s film is decidedly preindustrial, almost medieval in its preoccupations.

Nosferatu’s continuing appeal lies in its formal elements. The pictorial compositions are frequently stunning: Nosferatu, for instance, clinging to a window grid like a spider in a Bauhaus web. The shadow of Nosferatu’s extended talons glides up a victim’s bed-clothes, closing on his victim’s heart. Arches and shadows repeatedly unify and bisect the images, often simultaneously. The sails and rigging of the death-ship divide the screen into nearly abstract patterns of light and shadow, austere and almost oriental in their minimalism.

The extent of Albin Grau’s visual commitment to the material—as well as his fascination with the occult—can be seen in the extraordinary effort he spent in the creation of a single prop, the letter, or lease, filled with strange symbols that Hutter brings to Nosferatu from his mad employer. The document, front and back, is on screen only for a few moments. But a close analysis of frame blowups, published in the French film magazine Positif in 1980, shows that Grau utilized a complex synthesis of cabbalistic and astrological symbols that Nosferatu would take as favorable auguries for his purchase of the house. The letter recalls the earlier use of hermetic symbols by Stoker’s illustrators, and the widespread practice by members of secret magical societies of including alchemical or mystical signs in their signatures—a variation on the secret handshake, signaling others who knew the code. It is also possible that Grau was simply indulging his own interests in a manner wholly out of proportion to the requirements of the film. Certainly, the financial aspects of the production as a whole were totally out of balance and indicate unmistakable lapses in judgment; following the premiere, it would be revealed that Nosferatu’s publicity expenses had actually exceeded the cost of producing the film. And it seems to have occurred to no one that there were any copyright problems involved in an unauthorized

adaptation of Dracula. They had changed the names, after all. They had acknowledged the source, hadn’t they?

An elaborate premiere was held at the Berlin Zoo on Saturday, March 4, 1922. The publicity material struck forbidding chords:

Nosferafu—who cannot die!

A million fancies strike you when you hear the name: Nosferatu!

NOSFE

RATU

does not die!

A million fancies strike you when you hear the name: Nosferatu!

NOSFE

RATU

does not die!

What do you expect of the first showing of this great work? Aren’t you afraid? Men must die. But legend has it that a vampire, Nosferatu, “the undead,” lives on men’s blood! You want to see a symphony of horror? You may expect more. Be careful. Nosferatu is not just fun, not something to be taken lightly. Once more: beware.

The initial critical reaction in Germany was generally favorable. Profound metaphors were perceived, with Nosferatu and his accompanying plague representing aspects of human malaise, particularly the German soul itself in the wrenching years during and immediately following World War I. In an advance magazine piece called “Vampires,” Albin Grau himself noted, “You no longer see the terror of the war in men’s eyes: but some part of it has remained. Suffering and regret have shaken men’s souls and, little by little, inspired the desire to understand what caused this monstrous event that swooped down on the earth like a cosmic vampire to drink the blood of millions … .”

The film stirred its share of political controversy. The Marxist newspaper Leipziger Volkszeitunger railed against Nosferatu on the basis that its supernaturalism was a calaculated opiate for the working masses, “wrapping the worker … in a supernatural fog through which he can no longer see concrete reality.” Previously, it was “necessary to protect the people’s ‘religion,’ so that the people themselves could be kept sufficiently stupid for capitalist interests.” Now, “this dangerous nonsense about spiritualism and the occult, to which millions of disturbed souls have fallen victim since the war, represents, at least in part, a gamble that the world of industry has undertaken, intentionally and at great expense, to steer the working class from its political goals by contaminating minds with this [supernatural] epidemic.” With its unprecedented loss of life, the war had indeed spurred a spiritualist revival in Europe and America as survivors

sought comfort from an almost unimaginable grief. But the Leipziger Volkszeitunger offered no sympathy, only a materialist warning: “If these few lines suffice to put workers on their guard not to give their money to a cinema that is going to show them a propaganda film, financed by industry and intended to deaden their minds, the whole pretty plan will fail, and the phantom Nosferatu can well let himself be devoured by his own rats.”

But artistic and political considerations were soon overwhelmed by another kind of press coverage. Prana-Film, it seemed, could not pay its bills. The “new principles” of film production cited by Grau were unique indeed, in that they apparently included the mystical transmigration of funds. Inquiries by the press followed, and then attacks.

And then it was Florence Stoker’s turn.

The Society of Authors proceeded cautiously in the matter. Florence was advised that her sale of the German translation rights had had no bearing whatsoever on German film rights. The fact that she had sought membership only in a crisis also caused a few eyebrows to be raised as to the sincerity of her interest in the Society’s work as a whole. By the middle of May, the committee chairman had reached a compromise decision: the Society was willing to place the matter in the hands of its German lawyer, a Dr. Wronker Flatow of Berlin, “on the understanding that if the film company gives in, all well and good, but if they show a disposition to fight that we cannot take the case further on your behalf.” Thus, the Society was able to offer at least the appearance of chivalry without really having to make an open-ended commitment. It was far less than Florence would have wished, but at least she now had representation.

By June, Prana’s precarious finances had driven it into receivership. Thring wrote Stoker that “the film company had put up some foolish points as a defence. If the company has gone into liquidation it is quite clear that we shall not obtain any money out of them, but it might be possible to obtain the film, or an injunction against anyone who purchases it.”

Florence Stoker’s early letters over the Nosferatu affair are missing from the Society of Authors archives (now owned by the British Library), and it is not known whether she was even aware of an earlier, now-lost Hungarian film variously known as Drakula, The Death of Drakula, or Drakula’s Death (1921). Directed by Karoly Lathjay and photographed by Lajos Gasser, the film owed more to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari than to Dracula, but nonetheless was the first motion picture to exploit the name value of Stoker’s character, if not his plot. In Lathjay’s film, “Drakula, the Immortal One” (Paul Askonas) is the delusional alter ego of a former composer and music teacher now committed to an asylum. When the daughter of another inmate (Margit Lux) is terrorized by a pair of doctor-playing patients who want to operate on her eyes, she succumbs to a terrifying nightmare in which she is kidnapped by Drakula and taken to his castle for a black-magic wedding ceremony presided over by a dozen of his wives. The protective power of the crucifix is demonstrated, as are Drakula’s skills with menacing bedside hypnotism. The girl awakes in the asylum, where the delusional musician dies after boasting of his immortality and challenging another madman to fire a gun at him to prove the point.

Paul Askonas and Margit Lux in The Death of Drakula, the first film to exploit the name of Stoker’s creation

A 1923 novelization of the film (Courtesy of Lokke Heiss)

Even if Florence Stoker had learned of the Lathjay film, its relationship to Dracula was so tenuous that a legal action would have been almost impossible to mount. But in Nosferatu, the widow had found far meatier prey. Judging from Thring’s patient, if slightly exasperated responses, her correspondence was frequent and insistent. She had been wronged. She wanted justice. Above all, she wanted money.

By early August, the Society’s patience showed definite signs of thinning. The case had not turned out to be so straightforward, after all. Thring to Stoker, August 3, 1922: “I am sending you a copy of a letter I have received from our German lawyer. You will remember that this case was originally taken up in the hope that our Lawyer might be able to settle out of court. The question has now become so complicated, and the legal point so difficult, that I doubt whether the Society could afford to carry the matter any further … . Perhaps you would let me know whether you yourself would be willing to meet any expenses … .”

It was but the first of many times Thring extended his regrets that the Society could no longer pursue her case, only to reverse himself a few days or weeks later. Evidently the widow still had a number of close acquaintances in publishing with ties to the Society, and knew how to extract favors or apply pressure as needed. The specific deliberations of the committee are not recorded, but presumably another reason for the Society’s willingness to persevere was the unique and legitimate nature of Stoker’s case and its implications for literary con-tracts in the burgeoning age of cinema. It would be far from the last legal battle involving film versions of Dracula.

Cinema as vampire: monstrous dreams, projected outward, transfix the spectator/victim. Publicity drawings by Albin Grau (Author’s collection)

On August 22 a power of attorney was forwarded to the German lawyer, who had quoted probable fees of twenty-four thousand marks. Thring asked for an equivalent guarantee of twenty pounds (not an inconsiderable sum for Stoker, something like one hundred dollars in 1922 terms) to cover the expenses.

Meanwhile, Florence Stoker had learned of showings of Nosferatu in Budapest. The company had dared to claim bankruptcy while the film was still being shown and making money as far east as the Danube!

The strategy, now, was to pursue the receiver of Prana’s assets and liabilities rather than the offending officers of Prana itself. But the action threatened to become mind-bogglingly complicated: the Society would have to incur costs not only in Germany, but in every country where the receiver might attempt to sell Nosferatu. “If the receiver is an unscrupulous man of business,” Thring wrote Stoker, “he will know it won’t be worth our while to take action, and most probably trade upon this.” Obtaining injunctions in other countries could be “a very expensive and dangerous experiment.”

The Germans showed some small signs of yielding, and through the German lawyer made a small offer of financial participation, provided Stoker would allow them to use the title Dracula openly in England and America. Thring advised her against this line of negotiation, unless the Germans were willing to make her a substantial advance (they weren’t) and was generally pessimistic about any settlement paid in marks because of the huge difference in exchange rates. The German economy was on shaky economic footing since the war, and its currency fluctuated wildly. If she won German money, she very well might have to invest it in Germany for it to have any worth.

The case had now dragged on for a year. Florence Stoker continued to state her position, insisting that the Society take the matter seriously. There was a principle both of fairness and of law. Was the British Society of Authors really willing to let the work of a British writer be stolen simply because his widow had no money to fight the case? The issue was larger than Bram Stoker.

Thring’s exasperation shows through in a letter of March 17, 1923: “I am in receipt of your letter. I can but refer the whole matter to the Committee again. You might remember, however, the case would cost the Society a considerable amount of money and that you joined the Society only when you were in difficulties. The Committee of the Society are bound to consider themselves as Trustees for the subscription of those members who have subscribed to the Society for many years, and whose cases as it is cost the Society very large sums of money. Whether the Committee will take the view you take of the case is entirely for them to decide.”

Nosferatu springs from his hiding place in the hold of the doomed ship.

The vampire emerges from the hold to stalk the crew. Note the live rat on the actor’s elbow. (Author’s collection)

So skillful, however, was Florence Stoker’s behind-the-scenes lobbying that she was able to transform the Society’s original request for a twenty-pound guarantee into an offer of twenty pounds in advance of any damages the Society might recover for her. On April 12, 1923, Thring told Stoker that “I am instructed, however, to inform you, that this payment does not imply that the Society will—or bind the Society in any way—to take action on your behalf.” Such an exceedingly strange arrangement could only be construed in one way: as a payoff. The old lady was getting tiresome. Thring hinted again that it might be better for her to deal through the German lawyer herself.

Once more, in June 1923, the committee concluded that it could not embroil itself in the messy Nosferatu matter any longer, and that it was the longstanding membership of the Society that was more deserving of support. “Further,” Thring wrote, “it is most probable that the Prana Film Company, judging from their present methods, would refuse to pay any monies whatever even if judgement was secured against them, and would use every possible legal method to avoid such payment.”

This was not what the widow wanted to hear, so she ignored it, and again appealed to the committee. By this point it had to have been more than obvious to all parties that they were dealing with a ferociously determined woman, who was not going away. As she would not accept the “advance” of twenty pounds and allow the Society to quietly drop the case, it was difficult to know just what to do with her. It would be unseemly indeed to just cut her off. The whole matter required a certain tactful closure. She still had certain connections, with Heinemann, for instance, one of her husband’s last publishers and one of the most prestigious houses. One of Heinemann’s former righthand men, C. A. Bang, was now advising her about dramatic rights.

Between Florence Stoker’s steely determination and the seeming inability of the Society’s committee to deal decisively with her, the

matter dragged on long enough for a development to occur in Berlin. Prana’s bankruptcy files had been subpoenaed and the case had finally been fixed for a hearing on March 31, 1924.

In their quest for verminous verisimilitude, the makers of Nosferatu put out a casting call for rats. (Courtesy of Lokke Heiss)

The end, however, was not in sight. In July, the German court ruled against Prana. Florence Stoker was asking for payment of five thousand pounds from the receivers, the Deutsch-Amerikanisch Film Union, to give them title to the film. In August, the receivers refused the proposal and decided to appeal. It was not until February 1925 that the appellate court ruled again in Stoker’s favor, but apparently this, too, was subject to appeal.

Realizing that there was no possibility of obtaining money, the widow began to press for the outright destruction of all extant copies of the film, in negative and positive (she had considered taking

possession of the negative herself, but seems to have been advised against it).

F. W. Murnau, one of the cinema’s most visionary pictorialists, pictured himself in a stylized movie-magazine portrait from the 1920s. (Author’s collection)

No doubt at this juncture the story will begin to horrify film conservators and historians, as Florence Stoker attempts the obliteration of a classic film that she herself has never seen, or asked to see. Most “lost” films have vanished through neglect. But in the case of Nosferatu we have one of the few instances in film history, and perhaps the only one, in which an obliterating capital punishment is sought for a work of cinematic art, strictly on legalistic grounds, by a person with no knowledge of the work’s specific contents or artistic merit.

But the English widow knew her rights. And the copyright in Dracula was very nearly her only means of support. She had just granted a stage license to a man who toured the provinces, an actor-manager named Hamilton Deane. It wasn’t really a first-rate company and it wasn’t really much money and she didn’t really like the adaptation. You couldn’t really do a whole novel on stage, Deane had told her. Practical stage conventions had to be observed. Reading a book was different from watching a play. There would have to be cuts. She remembered, of course, the tedious staged reading at the Lyceum that had been so important to Bram and had turned out so badly. And so she had given

Hamilton Deane permission to do his surgery and make his play. She needed the money.

But at least she had given Deane her permission. This German thing was another matter. They had no rights—none!—and she would take her legal remedy.

In May 1925 there were more delays, and she was advised of the possibility of yet additional maneuvering and appeals. “I am quite prepared to carry on,” she wrote to Thring.

Finally, on July 20, word came from Berlin that Prana’s liquidator had withdrawn its appeal. The prints and negatives of Nosferatu were ordered destroyed. The German lawyer’s fees had been collected from the receiver, and Florence Stoker was in no further financial obligation. “The judgement now becomes a final one,” the Berlin solicitor wrote, to which Thring added a fervent postscript: “I am glad this matter is now at an end.” He had every reason to be: three years had now elapsed since the widow had first approached him.

But the widow’s waking nightmare over Nosferatu had barely begun.

The German court had provided no tangible proof of the film’s destruction, although the original negative never resurfaced. But as any reader of Dracula knows, a vampire has numerous hiding places, and unless the sanctifying rites are performed, he can live on indefinitely, watching and waiting, attacking at will.

In October, Florence Stoker received by mail the prospectus of a new organization that carried the name of her longtime friend Ellen Terry—now Dame Ellen Terry—as one of the founding members. The Film Society, as it was called, also boasted the sponsorship of George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Julian Huxley. The Film Society was dedicated to preserving the art of the cinema, and would arrange screenings in a manner patterned after private theatre clubs that had long been in vogue. It sounded like a worthy cause indeed. Then she looked at the list of films that were to be shown.

Prominent among them was “Dracula by F. W Murnau.”

Not only had they stolen it—now they were claiming authorship as well!

She called Thring. He advised her to send a registered letter forbidding any performance of the film. The Society’s organizer, a certain Ivor Montagu, whom she did not know, rang her up. The voice on the phone was unrepentant. As Stoker wrote Thring, “Montagu

on the telephone contends as the performance will be private, they have a right to give it. He admits the film was purchased in Germany, but would not say from whom, or whether it was already in this country.” Thring advised Montagu that the proposed screening was not quite private from the standpoint of copyright law, and that Mrs. Stoker was prepared to take full legal remedies.

Actor Max Schreck, sans horror makeup (Courtesy of Ronald V. Borst/Hollywood Movie Posters)

Vampires, according to literary and film tradition, are wise to secure an agent, slave, or protector in foreign lands they visit. In Dracula the point of contact is Renfield, who devours the flesh of small living things. However, in its travel to England and America as a film Nosferatu would display a distinct preference for vegetarians. The first was Ivor Montagu, the son of a wealthy, distinguished family who had turned communist as well as herbivorous. (In a bizarre misunderstanding, Montagu once let Shaw, another vegetarian, serve him a veal cutlet for luncheon. The young man was too intimidated by Shaw at the time to put up a fuss, and so, however reluctantly, dined on flesh and blood.) Montagu would later become an associate of both Alfred Hitchcock and Sergei Eisenstein, as well as an influential film historian. He was also one of the earliest proponents of film preservation.

The last thing on Florence Stoker’s mind was the preservation of Nosferatu. She wrote the American Society of Dramatists and Composers on the letterhead of her son’s accounting firm, Williams, Stoker, Worssam and Holland, alerting them to the spreading pestilence of Nosferatu. “I have for a considerable time past been in negotiation for a film to be made from this novel … the fact that a pirated version thereof was in circulation would prove to be extremely prejudicial to me.”

On October 10, Montagu wrote to Bang. “I must apologize for my shortness on the telephone yesterday … your call should not have been put through for I was in the middle of a meeting. But still, that is no excuse for me being rude.” Montagu explained that since “we do not admit the public, but only show pictures to our members (exclusively) without charge, copyright does not affect us at all. Of course, it has never been settled with the films, because there has never been any private society showing them before, but on the precedent of the rights and powers of similar societies for the stage, I do not think there is any question of our losing a test case if one were brought.” However, Montagu assured him “that if you could convince us that the showing of the film to our members would damage Mrs. Stoker in any way, we would not dream of sticking to our legal rights, and would probably abandon the film altogether rather than hurt somebody.” A few days later, he visited Bang, who was surprised at how young Montagu was. Bang impressed upon him his view that the film he intended to show his members was “stolen goods.” Bang also did some detective work of his own and learned that an importer—he couldn’t learn the name—had tried to place the film at several London theatres, but ran into problems with the censor, “who has condemned it as too horrible. The film therefore has no market value in this country and they have offered it to the Film Society free of charge.”

Montagu stonewalled on the matter of the agent. “No doubt he knows all about where the offer came from,” Bang wrote Stoker, “but he is evidently shielding them.”

Like Seward, Van Helsing, and Harker scouring London for Dracula’s safehouses, Bang, Thring, and company tracked the German vampire through commercial London, narrowing the search to an importer, Sargent’s Trust Ltd., in Chancery Lane. But the film canisters that contained Nosferatu were not to be found. By January, Thring in-formed

Stoker, “I beg to inform you with great regret we must drop the case of the film Dracula … . The Sargent’s Trust have already done everything to help us trace the man who actually held the film, but we find this person has disappeared entirely.”

Vampires aren’t supposed to throw shadows, but without them we would miss some of the great moments of German expressionism. (Author’s collection)

For the moment, there was nothing that could be done. The creature had succeeded in crossing the channel, and had penetrated London. It could reappear at any time, to taunt and to torment. Whatever her legal rights, there were certain irrational aspects of Dracula that were beyond Florence Stoker’s control. Uninvited, animated by the obsessions of others, the thing had achieved a life of its own and could move through her world as it pleased.