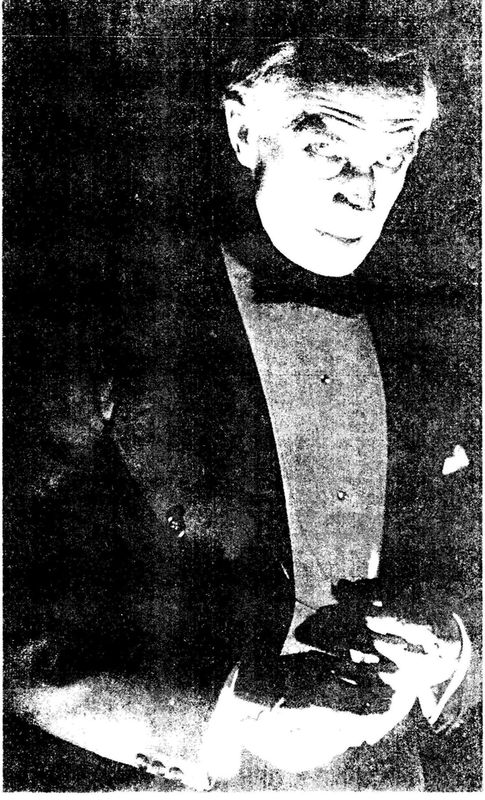

Actor Conrad Veidt, groomed by Universal as “the New Lon Chaney,” was the studio’s first consideration for Dracula. His appearance in The Last Performance (1929) was virtually a screen test for the role. (Photofest)

A DEAL FOR THE DEVIL

Or, Hollywood Bites

In which the picture people smell the blood, but hesitate still,

and say yes and no, and yes again, and in which

the German Count appears in New York, and Detroit, and,

must be stopped, lest he spoil the occasion.

and say yes and no, and yes again, and in which

the German Count appears in New York, and Detroit, and,

must be stopped, lest he spoil the occasion.

“I CONSIDER NO TIME MUST BE LOST OVER ENCLOSED,” WROTE FLORENCE Stoker to G. Herbert Thring. She scribbled with feverish speed, dropping prepositions and articles in her haste to reach the matter’s meat. Her handwriting was huge, fitting only a few sentences on each page; the widow’s eyesight was failing badly. “I have only just this minute learned that someone has sold the pirated film of the German Dracula to an American company … .”

This time, Thring was instantly supportive of the widow. “Whether the performance was private or public does not matter. No person has a right to retain a film which is an infringement of copyright,” he assured her. He examined the acknowledgment in the Film Society’s program which Stoker had sent him. “Can you tell me from whom the Universal Film Company of America purchased the film rights? Whether Dracula is copyrighted in America, and who is Mr. J. V. Bryson who has so courteously given consent to an infringing performance?”

James Bryson, head of the European Film Company, was in fact Universal’s point man in England, a flamboyant promoter and showman who had already been embroiled in a bizarre scheme to smuggle into England a print of Universal’s Phantom of the Opera as a publicity stunt. He had misrepresented the film as sensitive military material in order to obtain a British military escort—a photo opportunity, in short. The scheme backfired, a scandal ensued, and the Lon Chaney classic was actually banned from the British Empire for five years as a consequence.

After receiving an interrogating letter from the Society of Authors’ solicitors, Messrs. Field Roscoe and Company, the Film Society retained lawyers of its own, Gilbert Samuel and Company, who made a formal reply. The Film Society had seen the front-page announcement in To-Day’s Cinema (the lawyers explained) indicating that Mrs. Stoker had sold her rights to Universal. They then approached Bryson, who confirmed the story and referred to a cable he had received from Carl Laemmle, head of Universal in America, stating that the rights had indeed been purchased, and that he, as Universal’s British distributor, had no objections to Nosferatu’s being shown to members of the Film Society.

Florence Stoker was adamant. She had never heard of these people. She had never sold the rights to anyone.

C. D. Medley, of Field Roscoe and Company, told Thring he was skeptical of Bryson’s story, “particularly as I find it was he, or his company, who forwarded the announcement to the cinema weekly.” Bryson now disclaimed that he had explicitly given permission for the performance.

Stoker did not have a face-to-face showdown with Nosferatu’s aiders and abettors until February 7, 1929, when the Bride of Dracula met Nosferatu’s herbivorous henchman, their solicitors in tow. A tense meeting ensued, in which Montagu restated the history of the affair, and denied that he had been harboring the film since the previous controversy. (The program notes for the performance stated that the print of the film had been discovered, by chance, as stock footage being

readied for export to Australia in a safe located in the same room the Society’s technical staff happened to use.) He produced the original statement from Bryson’s office concerning the alleged Universal purchase, which only compounded the insult to Stoker: the draft notice contained a paragraph, struck before publication, to the effect that Stoker had been asking fifty thousand pounds, but Universal had been able to have its way with her for a considerably lesser sum.

Fifty thousand pounds! Stoker could not believe what she was hearing … the lies were bad enough, but … was it possible that she might be able to ask that much? The draft did not, however, reveal the final terms of the fictitious sale. But … fifty thousand pounds!

Montagu, round-faced, round-spectacled, an enfant terrible with artistic pretensions and communist leanings, must have been an almost incomprehensible figure to Stoker, and she to him. Stoker was born poor and had spent her life maintaining a precarious foothold on the middle class; Montagu had been born rich and now dabbled fashionably in socialist circles. He didn’t seem to understand the difference between art and thievery. He insisted that what he had done was completely innocent. He had probably been plotting this for years!

Stoker demanded that the film be turned over. Montagu replied that it would be distinctly hard for him to give up the film without being compensated for it—the Film Society had, after all, paid forty pounds for the print. Stoker fumed. The insolence of this creature! Was she now to pay for the privilege of being robbed? Subsidizing thieves—it was socialism at its essence! Stoker’s lawyer pointed out that the film was quite useless to him since he couldn’t exhibit it again, but Montagu explained that one of the objects of the Film Society was to collect and preserve films of artistic or scientific interest. Nosferatu in his opinion fit these criteria. He would, however, be prepared to give them a warrant that no future use would be made of the film during the period of Dracula’s copyright without Stoker’s express permission.

Stoker was outraged. She told Montagu precisely her opinion of the character of his infringement. The rights in the matter were hers, and not his to bargain. The film was not something to be preserved, but to be destroyed.

Medley pressed Montagu for information about additional prints of the film that might exist. Montagu alluded to one copy in use in

France—he had no direct knowledge of it, but had seen the advertisements in the Parisian newspapers. As for America, yes, he believed it had traveled there as well, by way of an organization called the International Film Arts Guild. At least one copy, and very likely more.

So it had already happened, exactly as she feared: Nosferatu had reached America with its relentless, infringing pestilence.

Medley advised Mrs. Stoker to ignore Montagu’s suggestion that they be permitted to hold the film “as a sort of curiosity upon an understanding not to exhibit.” He further advised her that, while the Film Society had made no profit worth mentioning in the affair, formal legal action might well be taken against Bryson and Universal, as a warning to the cinema trade that Stoker alone held the film rights and that “any person who attempts to interfere with her will be dealt with.”

The widow, however, backed off. “I am not anxious to go to law,” she wrote Medley, concerned that the Film Society might not be financially strong enough to pay the costs on both sides in the event of their losing an action brought against them. If they would pay the costs already incurred, the matter might be dropped. Bryson and Universal were unresponsive to requests for an explanation of their behavior. Stoker made no move to challenge them further. She couldn’t afford to alienate them. However outrageous their behavior, they were interested in Dracula, and they had more money to spend than she had ever seen at one time in her life.

By late March, the Film Society had agreed to turn over the positive print of Nosferatu in its possession. Stoker expressed some ambivalence or confusion over the means by which she might destroy the film. The matter was handed over to the lawyers. Field Roscoe and Company were similarly unversed in the requisite rituals. “I do not myself know how these films are destroyed or whether I have any means of doing it,” Medley wrote Thring, “but will consider the matter when I get it.” The record is silent on the exact fate of the film, but presumably the English print of Nosferatu was consigned to the flames around the first of April, 1929.

Did Florence Stoker ever actually see Nosferatu? After seven long years of doing battle, and finally capturing the enemy, it would be strange indeed if she didn’t insist on looking the thing in the face. But her letters leave the distinct impression that she considered the

film beneath contempt. To look at it might dignify it. Silent movie vampires could not be heard, and they were better not seen. If she had once been Oscar Wilde’s Cecily Cardew, she was now his Lady Bracknell, on this point, as indeed on all points, firm.

Nosferatu, of course, would go on to be recognized as a landmark of world cinema, elevating the estimation of Dracula in a way no other dramatic adaptation ever would, or ever could. With Hamilton Deane’s constricted adaptation, the piece had begun its descent into kitsch; Nosferatu, however, had mined Dracula’s metaphors and focused its meanings into visual poetry. It had achieved for the material what Florence Stoker herself would never achieve: artistic legitimacy. For all its popular fascination, Dracula would forever be an object of critical condescension.

Nosferatu was not Stoker’s only contretemps over the film rights. She had turned against C. A. Bang, who had been advising her on motion picture matters, when it was brought to her attention that his commission of 25 percent of her earnings might be vampirically high. A lawsuit and countersuit ensued. Stoker engaged the representation of the well-known play broker Dorothea Fassett, a partner in the London Play Company. “The Stokers were suspicious of all agents after the Bang business,” she later wrote. Fassett acknowledged that she had been instrumental in their getting rid of Bang, and had employed her own solicitors, at some expense, to lobby the Stokers’ lawyers and vouch for her good intentions. The cynical, chain-smoking, business-savvy Fassett was in many ways a caricature of the hard-nosed theatrical agent, and a sharp contrast to the Victorian Knightsbridge widow. But they had something in common: both women liked a fight. “Dorothea wasn’t truly happy unless she was in the middle of a row, and she always seemed to have five or six of them going,” remembered Laurence Fitch, a veteran British agent who worked for Fassett as an office assistant at the time of the Hollywood interest in Dracula. He remembered the regal F. A. L. Bram Stoker (as she often signed papers) “sweeping in and out” of Fassett’s Piccadilly office. “To a seventeen-year-old boy, one old lady tends to look like any other. But Florence Stoker certainly had presence,” Fitch recalled.

The alignment with Fassett was fortuitous for Stoker, and it is unlikely that a film sale for Dracula could have been made without Fassett as a mediating presence. But more important still was Harold

Freedman, head of the Brandt and Brandt Dramatic Department in New York. Freedman, who came into the Dracula film deal as John Balderston’s agent, displayed in many ways the antithesis of the aggressive, abrasive style that marked the wheeler-dealers of the period. Freedman was famous in literary circles for the understated, almost conspiratorial whisper in which he held client discussions. Discretion, tact, and quiet persistence were the Freedman hallmarks, and would eventually earn him legendary status among agents. (Among his biggest coups would be the film sale of My Fair Lady for $5.5 million plus a percentage, a staggering figure for the time.)

Fassett in London and Freedman in New York would be the two individuals most responsible for Dracula’s film sale to Universal. While most accounts credit the interest of Carl Laemmle, Jr., or the director Tod Browning’s supposed dedication to the project, it was Fassett’s hand-holding in London and Freedman’s quiet behind-the-scenes efforts in New York and Hollywood that would actually close the deal. The story, told here for the first time, provides a fascinating look at the reality of Hollywood deal-making in the days of the early talkies.

Even before her falling-out with Bang, Stoker had received some inquiries about film rights to Dracula. The vexing thing was, the success of the play in London and New York was spurring the real interest, not a renewed appreciation of the novel. The play was the thing, and the play and the book were very different animals indeed.

John Balderston was among the first to realize that Stoker was going to try to sell the film rights to the novel alone, and rid herself of any claims by himself and Hamilton Deane. Ironically, he had been aware of the Universal story for over a month before Stoker—and had his agent Harold Freedman contact Universal directly to confirm that they had not purchased the rights. Balderston was nonetheless sure that Stoker had been negotiating, with the desire to cut him out. He feared that “these people are so pig-headed and so stupid that they might let the film go smash rather than give us a percentage,” he wrote Freedman. “There remains the point, whether the film people wouldn’t pay us something on the side when they understood the position?” He suggested that there was a fine chance for Freedman’s “Machiavellian diplomacy.”

It was the beginning of a long string of mutual misunderstandings and mistrusts between Stoker, Deane, Balderston, and Liveright that would haunt the negotiations for a screen version of Dracula. Balderston was particularly stung by the seeming discounting of his own contributions. “Owing to the peculiarities of the people concerned, this play would not have got on in New York at all if I had not exercised my well-known powers of diplomacy,” Balderston wrote to Louis Cline. “Horace would be the first to admit that he was several times on the verge of chucking the thing. I did get around the old lady then, and I think I can do it again, but I doubt very much whether anybody else can.”

Deane and Balderston had had a previous, informal agreement to split equally any proceeds from a film sale. But now, Balderston learned, Stoker and her son had proposed to Deane that they sell the Deane version of the play, not the Balderston. Balderston tried to disabuse Deane of this notion, pointing out that the Dramatists’ Guild would undoubtedly back Balderston’s own claim. Hollywood would buy one thing and one thing only—equity in a success. “The Deane version not only would not have been a success [in New York] but was actually turned down by Liveright and everybody else before I came along.”

Liveright had by this point realized his terrible oversight in not negotiating any film rights in his theatrical contract. He, too, had presumed that a film version would go back to the book. Now he was faced with the necessity of having to purchase the film rights from Stoker in order to have any interest in them at all.

Balderston wrote Freedman: “Mrs. Stoker and I have become very friendly over the inequities of Bang, her confidential agent who has been robbing her for years … and she realizes that I have not been trying to rob her, as of course Bang told her I was, over the film. Her son also seems a decent chap and I am having lunch with him on Friday. He has the film thing in hand, and is dealing with Horace … .

“Mrs. Stoker, after some hesitation and consultation with her son, told me on Sunday that she has decided to sell all the rights to Horace. The price is, I believe, £4200 … this includes all the rights, talkies and everything. As she seemed friendly, although entirely ignorant on the whole subject, I explained to her that Deane and myself have a

distinct interest in the matter, if the play is to be turned into a talkie. This seemed a new idea to her. She had been previously led to believe that we were a pair of robbers trying to get the film rights away from her. I think I made her see that it is a matter of joint equity.”

Stoker asked Balderston if she should sell Horace the rights. “I didn’t give a definite answer, but I told her he undoubtably wanted to resell, which seemed a novel idea to her. She thought he wanted to produce the film himself.” Balderston pointed out the need to delay the release of any film for a few years, “as otherwise Horace might sacrifice all our royalties for a large price for the film people.” Liveright had, in fact, begun quietly negotiating with at least one studio. Stoker and her son took the matter under advisement, and delayed signing.

They decided instead to increase their asking price of Liveright to six thousand pounds.

Liveright didn’t have the money, and the first, lower offer was probably bluster. His finances, as usual, were in chaos. Instead, he appealed to Harold Freedman to offer Stoker an advance of one thousand dollars if she would permit him to continue his studio negotiations. He proposed a three-way split, a third to Stoker, a third to the playwrights, and a third to himself. It was a ludicrous, desperate offer and went nowhere. In addition, Liveright’s second road company of Dracula had gone bust due to bad planning and he was badly in arrears in royalties owed. He simply had no credibility. No doubt, he felt that Dracula’s stage success and subsequent attractiveness to Hollywood were largely his doing. But there was no denying that he had simply waived the film rights in what would become one of the great money-spinning literary properties of the twentieth century. Liveright’s fortunes in publishing were also at a low ebb, and his days with Boni and Liveright were numbered. One of the advertising illustrations that was traveling on the road with Dracula showed the vampire attacking a girl in flapper-style attire. Now, on the brink of the stock market crash, the picture had another, more resonant portent for Liveright, himself one of the leading symbols of the jazz age and its excesses.

Meanwhile, Dorothea Fassett had received a firm offer of six thousand pounds from an agent named Wilkes. The Stokers hesitated. Universal hadn’t been heard from, after all. They bided their time

through the spring of 1929, convinced that the value of Dracula could only increase. Their agents thought otherwise, and urged them to take the tide at the flood.

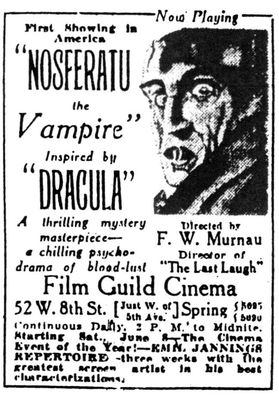

Nosferatu’s sudden appearance in a Greenwlich Village theatre threatened to derail the film deal. (Author’s collection)

The negotiations, however, were about to be interrupted by the Banquo-like appearance of an unwelcome shadow.

Nosferatu had surfaced in America.

First in New York with its teeming millions, then, emboldened, in Detroit, the German Count was stalking audiences with impunity. During the first week in June an advertisement ran in The New York Times: the “First Showing in America,” the ad proclaimed. “Inspired by Dracula,” the film was said to be “A thrilling mystery masterpiece—a chilling psychodrama of bloodlust.” Max Schreck’s face adorned the ad like the image on a postal stamp from hell.

Horace Liveright was among the first to take notice, and sent Louis Cline to see the film. It was showing at the Film Guild Cinema, on Eighth Street in Greenwich Village (decades later, as the Eighth Street Playhouse, the same site would be haunted by the long-running Rocky Horror Picture Show). The little-cinema movement had been gaining American momentum as reaction against the commercial giantism of picture palaces like the Roxy, and the Film Guild was one of

New York’s jewels. Architect Frederick Kiesler (1890–1965) had created a Bauhaus-deco extravangaza of a theatre, despite its small size. The screen was completely encircled by an iris-like proscenium Kiesler called a “screenoscope” with curtains that seemed to dilate rather than rise. The severe black-and-white color scheme was intended as a metaphor for the cinema’s essence of light and shadow. Constructivist-looking placards advertised “100% CINEMA—UNIQUE IN DESIGN—RADICAL IN FORM—THE HOUSE OF SHADOW SILENCE—REST FOR WEARY EARDRUMS.” All in all, it must have been one of the most delirious places imaginable to watch an expressionist film like Nosferatu.

Louis Cline had no impressions of the decor, at least not that he reported. He wrote a memo to Liveright on June 4: “There is no question … that Murnau made this film from the book by Stoker and he has put most of the book into the film except the three women in white [who] are conspicuous by their absence.” However, he concluded, “there is nothing as far as I can see that infringes on our version of the story. Of course the use of the word Dracula evidently enticed people into the small house. I had to stand almost through the first show [but] … when people saw what a boring picture Nosferatu turned out to be, there were plenty of seats in the theatre during the second showing last night.” Cline was not alone in his opinion of the film—a critical fashion for Nosferatu would not develop until after World War II. The New York Times called it “more of a soporific than a thriller” and commented on two audibly dozing audience members. The overall effect of the film, in the Times’s opinion, was “like cardboard puppets doing all they can to be horrible on papier-mache settings.” The New York Herald Tribune called it “jumbled and confused,” and, while praising its visual compositions, complained that the story “flopped woefully due to inexpert cutting or bad continuity.” Only the New York Post anticipated the film’s eventual classic status: “Not since Caligari has this reviewer been so taken with a foreign horror film as with F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu the Vampire … taken from Dracula, recently seen on the stage … and infinitely more subtly horrible than the stage edition. Mr. Murnau’s is no momentary horror, bringing shrieks from suburban ladies in the balcony, but a pestilential horror coming from a fear of things only rarely seen.”

Despite the predominantly bad reviews (or perhaps a partial cause of them) the 1929 American print, retitled Nosferatu the Vampire, may have been a substantially variant cut of the film. In Europe, a completely reedited version of Nosferatu was released the same year under the title The Twelfth Hour. The work of a former student of Murnau’s, The Twelfth Hour incorporated new footage as well as Murnau outtakes. On the basis of the published credits, the American print, too, varied substantially from the original—at least in terms of its titles and character names. For one thing, most of the character names were changed again. Count Orlok became “Count Nosferatu,” while the Renfield character, Knock, was called “Vorlock.” Other character names underwent changes as well, and the doomed ship, formerly the Emprusa, became the none-too-subtle Vamprusa. New York State Archives records show that the film was otherwise of virtually identical length to the original, and there is no record of whether the film was color-tinted, whether any specific music accompanied it, etc. One indication that some reediting may have occurred is the appearance in a French account of the name “Symon Gould” as being responsible for the montage, or editing, of the American version. The American intertitles—and perhaps the character names—were provided by the prose poet Benjamin De Casseres (a minor legend of New York’s bohemia whose career would eventually collapse under the weight of his eccentric right-wing politics), with Conrad West listed as “scenarist.” Symon Gould was the founder and director of the International Film Arts Guild, and proprietor of the Film Guild Theatre. A pioneer exhibitor of the art film movement in the United States, Gould had founded the Guild in New York at almost the same time as Ivor Montagu’s Film Society in London was formed. He was also the second vegetarian who would intercede on behalf of the German vampire. Far more ardent a herbivore than Montagu, Gould would eventually mount a quixotic presidential campaign against John Kennedy and Richard Nixon, running on the ticket of the American Vegetarian Party in 1960. Gould’s interest in blood themes led him eventually to take over the American distribution of Georges Franju’s gruesome slaughterhouse documentary Blood of the Beasts.

Florence Stoker proposed to write once more to the newspapers of America, alerting them to the menace of Nosferatu, but G. Herbert

Thring stilled her hand: “[Y]ou might not only prejudice your position but might lay yourself open to an action for libel if it is subsequently proved that the film was not an infringement of your copyright. We have at present no real evidence upon which to base a claim.” Thring’s opinion would prove prescient a few years later, when the American copyright status of Dracula would indeed come under serious question.

Harold Freedman drafted a letter to the Dramatists’ Guild on behalf of Balderston and Deane over the Nosferatu piracy, but it was never sent. The film was no longer being exhibited, and in any event was not taken seriously by most of the main players in the Dracula negotiations. As usual, however, the matter was far from at an end.

Florence Stoker’s worsening eyesight had progressed to the point that it required surgery, and October 1929 found her recovering in a nursing home. She thereafter moved to what would be her final residence, a small mews house off Wilton Place in Knightsbridge, a few blocks from Hyde Park Corner. The address was distinctly in the shadow of the elegant homes surrounding it. But at least it was still Knightsbridge, and if she didn’t have money or a fashionable front door, she still had her paintings and treasured souvenirs from the days of the Lyceum and Cheyne Walk. Unable to read or write, she dictated a few letters to her son and a companion. Stoker’s anxiety over Nosferatu may have been exacerbated by her inability to readily communicate her thoughts about it.

By December, Balderston updated her on the affair. Gould had scheduled Nosferatu for a return engagement on Eighth Street. “I am sorry to worry you again about this thing, but we have all tried our best to scotch this snake without complete success … if it ever came to a fight I should, of course, be willing to associate myself with you to the extent of my interest in the rights.” He assured her the following day that Gould and company were “small people who are quite irresponsible and they only show the thing on the sly in small houses and run away when you chase them. This is annoying and damaging no doubt, but it ought not to kill the market for the film when done properly and in a big way.”

Freedman worried, however, that Nosferatu had the potential to cloud negotiations for Dracula. The value of the sale was the offering of a clear title to the property. But when Nosferatu had surfaced in

Detroit, Louis Cline wrote Balderston that it had been “advertised frankly as Dracula.” Cline, who hadn’t been following the Nosferatu affair very closely, asked Balderston “if there is any dope you can get from Mrs. Stoker about who made the film she rejected. I intend booking Dracula … on a swing out through Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City and Denver, but if this film is going to beat us into these places, it is going to hurt us.”

Freedman contacted Gould. Unlike Ivor Montagu, Gould did not seem interested in retaining the film as a curiosity, or for any other reason, if cash could change hands. Furthermore, Gould contended that accepting anything less than five hundred dollars was not worth his while—he could easily get that much by sending the film back to Germany. Freedman wrote Balderston, “I am trying to get him down to about $300—if not, I’ll pay him $400 on the following basis: that, if during the next six months no positive print appears in this country, I will turn the money over to him.” Meanwhile, Gould was to relinquish his positive print and all information as to the location of the negative and the prevention of any further piracy that might interfere with the film negotiations.

Gould made no immediate response. The German Count could repose in his film canisters until the most advantageous moment.

Dorothea Fassett was getting very nervous. “I am strongly of the opinion that the value of this property is going down every minute … if any of us are to make anything out of the film rights, we ought to do it now.” She reported that an offer was being tendered to Stoker through the International Copyright Bureau—but only if they would bring the price below nine thousand pounds (a pound sterling was worth about $4.75 at the time). The offer was refused. Raymond Huntley’s name appeared in cables as a suspected party to negotiations with Columbia Pictures. The offering price quoted was twenty-five thousand dollars. (Huntley remembered nothing of the affair.) Stoker insisted on thirty-five thousand, with three-fifths guaranteed to her, and two-fifths to Balderston and Deane. The deal fell through. In the matter of actors, Universal had lost Conrad Veidt, who returned to Europe rather than risk the talkies with his heavy accent, and their next choice, Lon Chaney, was under contract to Metro. And above all, Freedman’s direct contacts with various picture executives produced a consensus: the price of Dracula was simply too high.

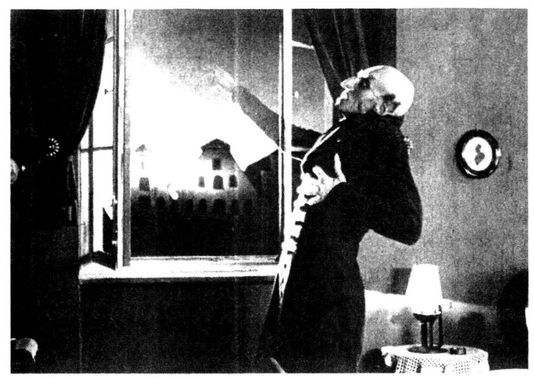

A vampire was destroyed by sunlight for the first time in Nosferatu. Unfortunately for Florence Stoker, the film itself was not so easily dealt with. (Photofest)

Stoker, however, trusted her Bracknellian instincts on Dracula: the floor for the property was now thirty-five thousand dollars. Stock market crash or no.

In January, Freedman apprised Balderston of the situation. The situation with the film rights, he wrote, “still seems to narrow itself down to the Universal proposition. The Laemmles are coming here next week and I am going into it with them then. Lon Chaney has finally decided to do a talkie with Metro. Universal were unable to wean him away at the time this thing was hot here … . If he doesn’t get along with Metro on his first picture, then I suppose, there will be some chance of Universal’s getting him.”

By mid-February the situation hadn’t changed. “Universal are still very interested in it,” Freedman wrote, “but won’t do anything unless they can get Chaney.”

Universal had good reason to want Chaney. The actor had helped put Universal on the map as the star of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), which also made him a star of the first magnitude, a specialist in deformed characters and grotesque makeup. The production itself

became something of an opera bouffe as Chaney slugged it out with the nominal (and, to most accounts, thoroughly incompetent) director Rupert Julian for creative control. After multiple preview versions and a radically changed ending, the film emerged an expensive headache, but nonetheless a box office bonanza. Universal originally developed its ornate adaptation of Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs (1928) as a vehicle for Chaney and his Phantom leading lady Mary Philbin, but Chaney, previously a freelancer, had meanwhile signed a term contract with MGM. Universal’s bid for a loan-out collapsed, and Chaney was replaced by Conrad Veidt, the German star of expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and other macabre films. Curiously, Chaney’s next assignment at MGM, Tod Browning’s London after Midnight (1927), involved makeup remarkably similar to the one he would have worn in The Man Who Laughs—a hideously toothsome, distorted grin, the corners of his mouth drawn back by hooks attached to the sides of his dentures. London after Midnight was also a transparent attempt to capitalize on the current stage success of Dracula. It featured a heroine named Lucy, menaced by a fanged, vampirish creature in a batlike cloak, who arrived on a cloud of mist from a ruined estate next door. There was a concerned fiancé, a terrified chambermaid, demonstrations of hypnotism, and a Van Helsing-like investigator wise to certain nonculinary uses of garlic. Unlike Dracula, London after Midnight revealed its vampires to be theatrical stooges in an elaborate plot to trap a murderer. Chaney played both the investigator and the bat-man.

It is an oft-repeated Hollywood factoid that Chaney coveted the role of Dracula, and, according to a later New York Times retrospective piece, had discussed the property with Tod Browning from the beginning of their professional collaboration in the 1920s. “Chaney had a full scenario and a secret makeup worked out even at that early date,” the Times reported. No such scenario has ever surfaced, but Dracula certainly would have offered Chaney a spectacular opportunity for makeup effects involving bat and wolf transformations, rejuvenation, menacing dental prostheses, and the like. His Phantom of the Opera had already slept in a coffin, and the sheer physical spectacle of his scaling the walls of Notre Dame in heavy body makeup only hinted at what he might have devised for Count Dracula’s lizardlike wall-crawl.

Publicity cartoon of Bela Lugosi and Hazel Whitmore during the West Coast tour (Author’s collection)

In early 1930, Harold Freedman assured John Balderston that he would talk to Chaney personally on an impending West Coast trip. As Freedman had previously noted, Junior Laemmle indeed had made a clumsy bid to “wean” Chaney from Metro for a series of talkies in 1929, including a remake of Tod Browning’s Universal silent hit Outside the Law (1921), in which Chaney had starred; a partially dubbed version of The Phantom of the Opera; and, potentially, Dracula. Since

Universal still hadn’t acquired the rights, the proposed agreement covered the eventuality with the following, amended language: “It is being understood that should the artist render services in the photoplay ‘Dracula,’ he will portray the role of ‘Count Dracula.’”

Universal’s bid didn’t fly. Perhaps with opportunistic calculation, it had coincided almost exactly with the suspension of Chaney’s contract by Metro because of the actor’s health. A nagging bronchial complaint kept him out of work for nearly half a year. Eager to get their part-talkie Phantom reissue into the theatres, Universal made a legalistic end-run around Chaney’s contractual refusal to have his voice dubbed by introducing a shadow figure, ostensibly the Phantom’s helper, who would speak the necessary dialogue and be accepted by an inattentive audience as Chaney himself. None of this could have endeared Universal to Chaney or Metro, and may well have been the nail in the coffin for Chaney’s ever acting in Dracula for the Laemmles, whatever the terms.

In March 1930, Dorothea Fassett wrote Freedman that Florence Stoker’s sleep was once more being disturbed by thoughts of Nosferatu. “She would like to have details as to the film’s career,” wrote Fassett dryly, “and know whether it just died or whether some arrangement was made to kill it.” Neither had occurred. And Gould was nowhere closer to revealing the film canisters’ whereabouts.

By early spring, possibly because of the growing awareness of the enormous potential in talking pictures, and despite the international financial mess, the nibbling started again. On March 13, Freedman cabled Balderston: INFORMED HORACE DRACULA CAN BE BOUGHT REASONABLY I HAVE MATTER UP WITH METRO UNIVERSAL PATHE COLUMBIA. On April 8, both Bela Lugosi—who had earlier requested and been denied a renewable six-month option for two thousand dollars—and his manager Harry Weber wired Freedman that they had lined up a deal for forty thousand dollars, cryptically promising the biggest studio, an excellent, reputable director, and, most importantly, a willingness to buy and produce Dracula with Lugosi as the star. The name of the studio was revealed two days later when a West Coast play broker named William Dolloff wired Freedman with a counteroffer: BELA LUGOSI SPOKE SPOKE TO ME IN REFERENCE PICTURE RIGHTS DRACULA STOP CAN OBTAIN HIGHER FIGURE FOR RIGHTS THAN METROS OFFER STOP PLEASE HOLD OFF NEGOTIATIONS. Dolloff’s deal—allegedly for

fifty thousand dollars—fell through when his purchaser grew skittish over Horace Liveright’s lingering involvement in the project and confusion over who actually held the rights. Liveright had sold his publishing interests and was now on the West Coast working for Paramount Publix Corporation on salary as a “production associate,” and still vainly trying to raise the purchase price for Dracula. Although Paramount boss Ben Schulberg had some interest in a film version—possibly as a result of Liveright’s prodding—almost no one else on the lot was enthusiastic. In April, Paramount story editor E. J. Montagne gave Schulberg his opinion that the theme was “strictly morbid” and might run into problems with the recently inaugurated Production Code. Montagne felt that “the very things which made people gasp and talk about it [on stage], such as the blood-sucking scenes, would be prohibited by the code and also by censors because of the effect of these scenes on children.”

The fact that Metro considered Dracula with Lugosi and not Lon Chaney, whom they had under contract, is interesting and suggests that his director, Tod Browning, was fully aware of his star’s failing health—so much so that he, and the studio, were willing to do Dracula without their most bankable asset, the Man of a Thousand Faces.

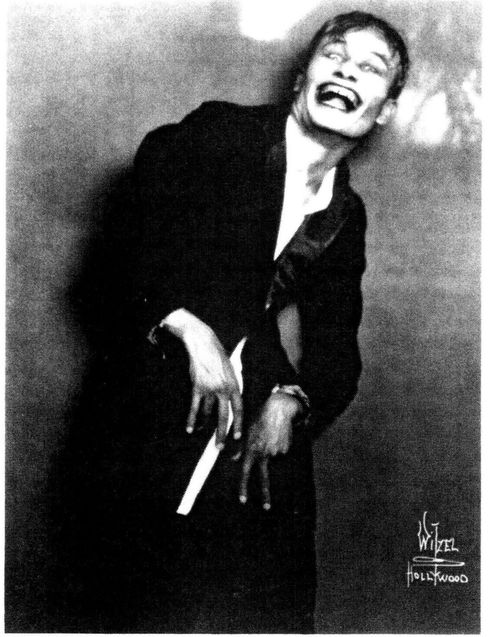

Bernard Jukes, the actor who was making a career out of playing Renfield on the stage, also became party to the negotiations in the spring of 1930, and apparently came close to securing a studio offer. The actor seems to have promoted the property, and himself, fairly aggressively; a series of startling publicity portraits of Jukes as the fly-eating maniac made the rounds of the studios, but finally were to no avail.

Discouraged with the sluggish, approach-avoidance stance of the studios, Harold Freedman made an expensive trip to the coast to bring the matter to a head. Arriving in May, he found the Universal situation “fairly cold” with Metro and Paramount Famous Lasky as the more likely candidates. “I got at Universal through [an] entirely oblique angle of a director and actor who I happened to interest, and through my stimulating a certain amount of interest with Metro and bringing Famous to a point where I forced Universal after several visits and after breaking through a lot of opposition, to take the picture rather than to see it go to Famous or Metro.” Freedman added that

he “had to get several directors interested in the proposition and one or two individual producers” before Universal agreed, in late June, to buy Dracula for forty thousand dollars. As Freedman later explained, “I finally put through the sale in face of Mr. Laemmle, Sr.’s definite written objection to the purchase of the picture.” As the elder Laemmle later told an interviewer in a discussion of Frankenstein, which Universal produced the following year, “I don’t believe in horror pictures. It’s morbid. None of our officers are for it. People don’t want that sort of thing,” he said. “Only Junior wanted it.”

Lon Chaney’s Dracula would likely have been a very different creature from the one with which we are now familiar. Here is Chaney’s pop-eyed, razor-toothed conception of a vampire in London after Midnight (1927). (Photofest)

Junior hadn’t always been a junior. Born Julius Laemmle, the son of the former Oshkosh, Wisconsin, haberdasher and self-made movie mogul had inherited the control of the studio on his twenty-first birthday. In a bizarre reciprocal gesture that suggests a plot from a morbid German doppelganger film, the diminutive young man relinquished his own name and identity: Julius died and was resurrected as Carl Laemmle, Jr. His abilities and achievements are still a matter of debate, but he did make one indelible contribution to American culture: the Hollywood horror movie. According to his cousin, dancer/ actress Carla Laemmle (who, like many other family members, lived in a bungalow on the Universal lot), Junior “loved everything macabre.” He was also a morbid hypochondriac who kept a virtual pharmacy in his office, was terrified of germs, and was even said to line his underwear with sanitary napkins to protect his genitals from contamination. His most memorable body of work, the Universal horror classics, would be notable for its ongoing obsession with characters who cheated death.

It would be fascinating to know Freedman’s precise tactic for mediating between father and son over Dracula, but even with Balderston he was tantalizingly reticent, stating only with implied exasperation that “there is no use going through the various things that had to be done to get the thing over.” Universal had agreed to agree, but the contracts had yet to be signed. And it was at this juncture that two unwelcome guests decided to make their presences known, and, perhaps, to spoil the occasion. One was Nosferatu, the vampire. The other was Horace Liveright, the producer.

Symon Gould had decided to bypass Freedman and approach Universal’s New York office directly, asking a flat payment of one thousand dollars to relinquish his print of Nosferatu. Universal balked. Associate producer E. M. Asher was under pressure to obtain the film; on July 19, he wired Freedman asking for assistance in obtaining Symon Gould’s print on a rush basis at a reasonable fee. Asher seems to have been more interested in studying the film than in destroying it; the Universal scenario department was already encoun-tering

major difficulties over its screenplay treatment. Why not see what had already been produced?

Actor Bernard Jukes campaigned unsuccessfully for the film sale. This maniacal publicity portrait was his calling card. (Author’s collection)

Gould wouldn’t budge. Asher asked Freedman to employ some personal diplomacy. Universal was willing to pay two hundred dollars for a ninety-day “rental.” Freedman warned Gould that the film

had no future commercial use, and that he could be enjoined against exhibiting it. Gould responded by wiring Carl Laemmle, Jr., directly: PLEASE WIRE DECISION REGARDING DRACULA PRINT. Laemmle told Gould his terms were unreasonable. Asher authorized Freedman to pay up to four hundred dollars—and to rush the print by airmail to Universal City.

Simultaneously, Horace Liveright, stung over being closed out of the Dracula negotiations, told Freedman that unless he received a financial consideration, he would file a lawsuit against Universal on the basis that its film adaptation constituted unfair competition to the stage version, in which he still held rights. He knew that Universal would never sign if there was even the slightest possibility of litigation that might prevent the film from being released. He also insisted that his share be paid not by Universal but by the owners—Stoker, Balderston, and Deane, with whom he clearly felt the need to settle a score.

To Freedman’s relief, he did not hold out for an exorbitant amount of money—Liveright wanted cash, needed it badly, and was not really looking for a protracted fight. The producer finally accepted forty-five hundred dollars in exchange for a quitclaim waiving all film rights to Dracula. Freedman was not, however, able to persuade Stoker and the playwrights to pay any more than one thousand dollars. Universal quietly made up the rest. Liveright was never told how little his partners had actually paid him. “It will be fatal if Liveright should know before the execution of this deal that the owners are only paying $1000,” wrote Freedman to Fassett on August 13. Fifty percent of the thirty-nine-thousand-dollar balance, minus agent commissions, went to Stoker, and 25 percent to each of the playwrights.

That left only the matter of Symon Gould and his vampire shadow in nitrate.

Freedman continued his dickering with the exhibitor. He wired E. M. Asher: BELIEVE CAN GET PRINT FOR FOUR HUNDRED DOLLARS DOUBT WHETHER ANOTHER IN EXISTENCE WIRE ME IF WILLING PAY THIS. Universal was willing. On August 13, the studio forwarded a check for four hundred dollars to Brandt and Brandt, and, two days later, they took possession of the film. Harold Freedman’s covering letter took no chances, legalistically: “This, I presume, is the print

you intended when you wrote me about sending you a print of Dracula. We have no print of Dracula, as you know, as we have made a deal with you for the motion picture rights of this play.

“Nosferatu, the Vampire has been adjudged by the courts to be a violation of Mrs. Stoker’s rights, and the courts have ordered the prints destroyed. I am turning it over to you for the purposes of destruction and in view of our contract with you for the delivering over to you of the rights to Dracula for motion picture purposes.” No doubt, Harold Freedman didn’t believe for a second that Universal was actually going to perform a sacrificial rite over the film—their interest in Nosferatu was a far more practical one. Nosferatu had infringed, and now might be infringed upon itself, cannibalized and reborn. In its marriage to the cinema, Dracula would become an unstoppable, unquenchable fixture of the public imagination.

The nuptials, however, would prove a bumpy nightmare indeed.