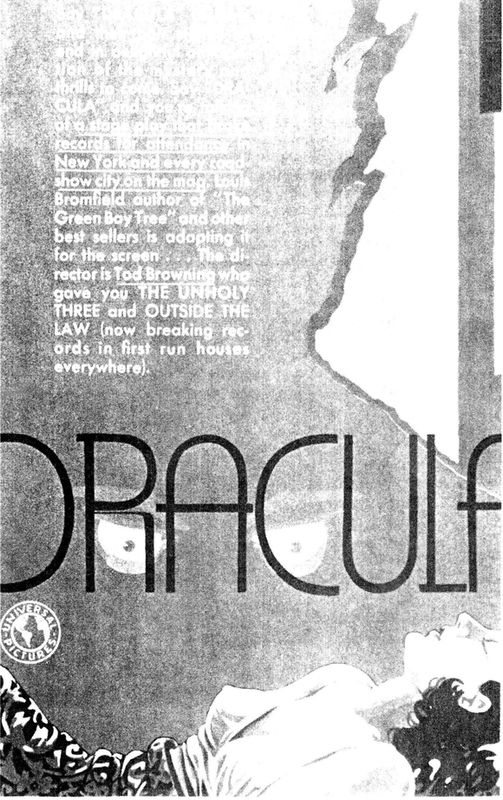

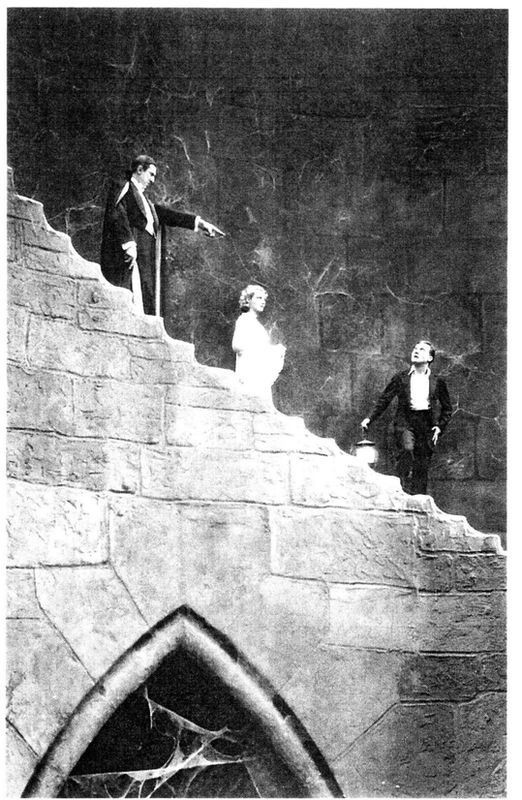

The preproduction trade advertisement for Dracula promised a film both literary and erotic. (Courtesy of Ronald V. BorstlHollywood Movie Posters)

THE GHOST GOES WEST

In which the Laemmles build a castle, but have no tenant,

and in which the cinematic rites are finally administered,

but the director is odd, and requires armadillos,

and the thing costs too much, but needs to be finished.

and in which the cinematic rites are finally administered,

but the director is odd, and requires armadillos,

and the thing costs too much, but needs to be finished.

IN ACCORDANCE WITH ITS INTENTION THAT DRACULA BE A “PRESTIGE” effort (“A Universal Super Production,” as they put it in the trades), the studio announced the signing of Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Louis Bromfield to write the screenplay. Bromfield had been lured to Hollywood by Samuel Goldwyn some months earlier, but after being given nothing to do for nearly half a year, he paid Goldwyn ten thousand dollars to be released from his contract. Junior Laemmle claimed to have hired him on the strength of his Pulitzer novel, a New England family saga called Early Autumn (which Laemmle’s publicists purported the mogul had actually read), and his established reputation as a Broadway dramatist.

It is difficult to imagine a writer farther removed from the world of Dracula—or Hollywood, for that matter—than Louis Bromfield, and it is likely that Universal wanted to exploit the publicity value of Bromfield’s name and his serendipitous leave-taking of a rival studio. Although his novels are largely forgotten today, Bromfield was a prolific and popular writer of a versatile temperament, though his tendencies toward political reaction and the championing of the “natural aristocracy” would begin to put him out of public favor during the years of the New Deal. Genuinely curious and enthusiastic about the creative potential of talking pictures, Bromfield recorded his impressions of the film colony in a Sunday feature in the March 30, 1930, issue of The New York Times: “There is an intelligence and talent gathering in Hollywood as it never gathered before. It is most hopeful, most promising. The talkies offer a new style, much more interesting to work in … . I believe that some day they will assume proportions as an art form as great as Anglo Saxon literature. I really do.”

Bromfield, who had never been west of the Mississippi, was entranced by the benevolent climate, the clean air and sunlight, the endless groves and flowering plants. Later in life he would devote much of his energy and writing to farming, agrarian reform, and conservation; it is easy to understand the seductive spell California cast over him. Friends, he said, had tried to warn him. “I was told that I was about to lose myself in a world that consisted physically of a valley between some mountains owned entirely by picture actors, directors, oil speculators and realtors and built over with dwellings that vaguely resembled yurts, pagodas, tepees, pueblos, igloos and medieval castles. Spiritually, the place was simply desert. All art, all spirituality withered when brought within ten miles of Hollywood.”

Like Harker on his way to Transylvania, Bromfield jotted down his impressions of the local landowners and peasants. He saw his newly adopted milieu as stratified into three separate castes—the native Californians, whom he idealized; the glamorous picture people; and desolate emigrés from the American elsewhere. The castes never mixed. And, as if in anticipation of Nathanael West, over them all hovered “a swarm of locusts composed of realtors, cult-leaders, religious prophets and radio announcers, who talk far too much.”

Elsewhere in the article—which vacillates weirdly between wideeyed optimism and revealing cynicism—Bromfield notes with evident distaste the “religious cranks, the dog poisoners, and in general the collection of freaks who have descended on Southern California … .

It is cheap and easy to accuse the picture industry of fantastic houses and fantastic decoration, but it’s a false accusation … . The responsibility lies with fat, middleaged and elderly women from the Middle West, who after years of prairie life have released their sublimated libidos in a perfect orgy of overstuffed sofas, Grand Rapids Louis Seize and boudoirs that would have put Anna Held to shame.”

Bromfield, at this point, had no conception of the degree to which Dracula—and horror movies in general—would eclipse Grand Rapids Louis Seize as an outlet for sublimated libidos. Horror movies of the genuinely fantastic, supernatural variety had not been invented yet, at least not in America, where conventions dictated that supernatural occurrences always be “explained away,” usually as the disguise or machinations of a criminal. In a sense, Bromfield was being asked to create a genre, and his first, intuitive effort has a certain significance.

In late July, before the rights to the novel and the play had been formally acquired, Bromfield was set to work under Erwin Gelsey, head of Universal’s scenario department. Glowing press releases were submitted to the trades heralding the arrival of Junior Laemmle’s literary pet, and the formidable battle he faced. According to the July 26 Hollywood Filmograph, “Dracula, one of the most unique stories brought to the stage in years, requires not only the sympathetic understanding of its screen adaptor but the technical skill of a writer experienced in the development of extraordinary dramatic plots.” The assignment was regarded, ominously, as “particularly difficult.”

Bromfield soon found out why. Universal was in the process of buying the rights to both the novel and the stage play. The problem was, neither had very much to do with the other. The Deane dramatization had dispensed with most of the novel in order to make it producible on a shoestring, and its dialogue was almost literally unspeakable. The Balderston adaptation was a vast improvement, but the play doctoring required for Broadway had resulted in a piece that was even further removed from the book. And the book itself was a problem. Almost none of Universal’s internal reader reports on the novel had been favorable. Only one predicted box office success (“It will be a difficult task and one will run up against the censor continually … but there is no doubt as to its making money.”) All the others considered the story frankly repellent. “ABSOLUTELY NO!!” one memo began. “In the first place, it would be impossible to translate

this novel of horrors to the screen. And, if it were possible, who would want to sit through an evening of unpleasantness such as a picture of this type would afford?” A cynical studio emissary who attended the Broadway premiere in 1927 had it both ways, conceding that Dracula had the makings of a great picture, at least from a dramatic and pictorial standpoint, but warned that the public was not likely to appreciate the achievement, and that a screen version might even be a violation of industry ethics. Bromfield truly had his work cut out.

It would have been much better to throw out the play and start with the book. But Universal was spending forty thousand dollars on three separate properties—no, not just three, there were four! A novel and three different stage adaptations, including that ghastly vanity production of Mrs. Stoker’s, the Morrell thing, and the studio wanted its money’s worth out of all of them.

In addition, two treatments had been already prepared, one by Frederick “Fritz” Stephani and another by Louis Stevens. Stephani had grappled somewhat listlessly with both the novel and the Broadway play, and added a few surreal touches of his own. Dracula, for instance, was to make the trip from Transylvania to England in an airplane outfitted with enormous bat-wings. Stephani’s aerodynamic imagination would find its niche a few years later at Universal, when he worked on the first Flash Gordon serial.

Bromfield followed his instincts as a novelist, and turned directly to Stoker’s book for inspiration. The material was certainly rich, though the epistolary style was a problem. Paying lip service to Stoker’s conceit, Bromfield’s treatment opens with an over-the-shoulder shot of Jonathan Harker writing a letter from his room in a Transylvanian inn at the height of a raging blizzard. Thereafter, the technique is dropped, and Bromfield continues with an enormously visual and evocative re-creation of Harker’s journey to Castle Dracula, with detailed descriptions of fantastic settings and winding, torch-lit staircases, all perched on a two-thousand-foot precipice.

Some early concept sketches by the scenic artist John Ivan Hoffman—probably inspired by the Bromfield treatment—have survived, showing a caped superman dashing down a gargoyle-decorated staircase. Bromfield’s visions would prove ultimately too ambitious for the studio’s budget, but they are certainly in keeping with the spirit

of Stoker’s original. The screenwriter obviously had in mind the kind of meticulous adaptation of English novels in which MGM would later specialize. Unfortunately, Universal’s financial health was becoming increasingly precarious. A year after the stock market crash, the studio had sharply curtailed its activities, producing fewer features on smaller budgets. Dracula would be a “Super Production” in relative terms only; its $355,000 budget was above average for the new streamlined operation, but only a fraction of the $1.45 million Universal had spent on its last “prestige” film, All Quiet on the Western Front.

Bromfield began with Stoker’s Dracula—a cadaverous old man with white hair and drooping mustache, a completely different figure from the suave Mephisto in evening clothes that had been popularized on the stage. How, then, was Bromfield to reconcile the book and the play? In a clever bit of inspiration, Bromfield found the means—Dracula would be two people. Traveling to London and drinking new blood, he would simply be rejuvenated into “Count de Ville,” the drawing-room Dracula of the theatre. (Stoker had employed the pseudonym in passing.) Only in moments of blood-lust would he revert to his former, novelistic aspect. Thus, the studio could have things both ways, and get a free dollop of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to boot.

It was an uneasy dramatic device, but probably a good political move on Bromfield’s part, since it seemed to reconcile the unreconcilable. Other Bromfield choices are less than inspired. He introduced dubious comic relief in the guise of a new character in London, a neighbor of the Sewards known as “Mrs. Triplett.” The part was specifically intended—at least by Bromfield—for the hefty comedienne Alison Skipworth, a performer who could easily have been cast as one of Bromfield’s overstuffed prairie emigrés. Mrs. Triplett was to be the owner of Carfax Abbey, landlord and bridge partner to Bromfield’s supernatural aristocrat. Due to his extrasensory powers, of course, Dracula runs rings around Charles Goren. Yet the vampire is unmasked during a card game, when Dracula fails to reflect in Mrs. Triplett’s compact as she powders her nose.

It is not known whether Bromfield added this material due to studio demand or as his own cynical sop to the compromising realities of the project. For Samuel Goldwyn, he had been given nothing to do; for Universal, he was being asked to do the impossible. And whatever

their literary and cinematic merit, his contributions, if filmed, would enhance the studio’s prestige at the expense of its budget—the construction of the oversized sets for Dracula’s London and Transylvanian lairs, as envisioned by Bromfield, would render the film unproducible. Bromfield’s honeymoon with the studio was short. Within a few weeks of his arrival at Universal City, he was being shadowed by screenwriter Dudley Murphy, who accompanied Bromfield and Universal associate producer E. M. Asher to Oakland, where Bela Lugosi was appearing in a stock production of Dracula at the Fulton Theatre. Lugosi was no longer associated with the national road company, then playing in the East, having held out for more money than Liveright was willing to pay. Raymond Huntley, despite his misgivings about the production, had accepted the role. The Fulton venue was probably not the best showcase for Lugosi to be seen in by Universal; aside from the second-string cast, there were half-empty houses during the Oakland engagement—weak evidence indeed of Lugosi’s box office appeal to an increasingly cost-conscious studio. Despite some unofficial mumbling in the press that Lugosi had won the film role, the real point of the Bromfield/Asher/Murphy trip was most likely to study the cost-saving possibilities of the stage version over the book.

Bromfield was not the first literary author to be pulled into the crushing machinery of the Hollywood studio system, and he would not be the last. Several months later he told a fan magazine, “Work in Hollywood from the writer’s point of view can be colossally unsatisfactory and there are plenty of discouraging moments when bit by bit you see your idea being transformed into something that seems new and unfamiliar.” With passing years, his view of Hollywood would become even more negative.

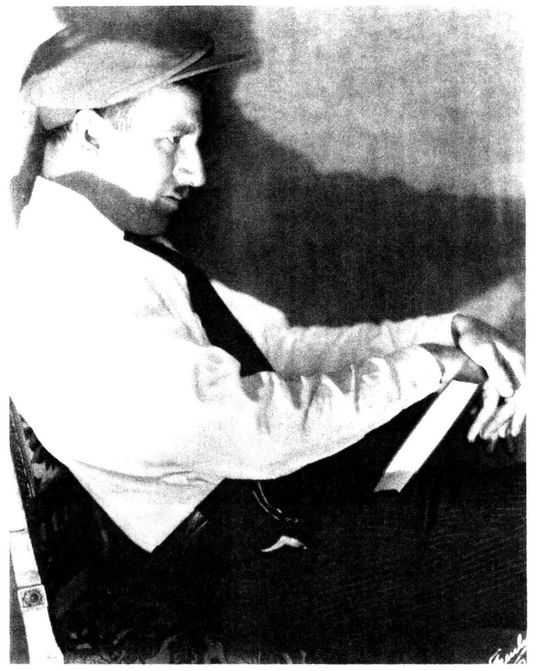

Shortly before Bromfield began work on Dracula, Universal formally announced Tod Browning as director. Browning had been Lon Chaney’s director at Metro, and it is possible that Universal signed him for a multi-picture deal in anticipation of also luring Chaney for Dracula. A Chaney picture—any Chaney picture—spelled box of fice, and a Browning/Chaney collaboration would be considered all the more bankable. Browning, a native of Louisville, Kentucky, who got his start in show business as a sideshow performer, shared Chaney’s fixation on twisted bodies and twisted plots.

To this day, Browning remains a maddeningly difficult director to

assess. On one hand, his films possess a thematic consistency almost unparalleled in film history; an obsession with the bizarre and grotesque, with the plight and vengeance of the social outsider, and a fascination with the tawdrier aspects of show business—carnivals, sideshows, fake mediums, and confidence games—all of which become skewed metaphors for unhealthy human relationships. Browning would bring these obsessions to a climax in 1932 with Freaks, one of the most notorious films ever made, featuring real circus freaks who gruesomely avenge themselves on a beautiful, treacherous woman. Originally intended as a silent film vehicle for Chaney, Freaks ended up a box office disaster in America, and it was banned in Britain for almost three decades.

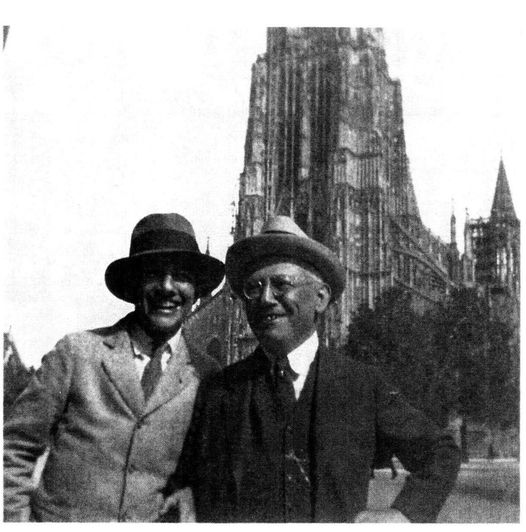

Carl Laemmle, Sr., (left) and Carl Laemmle, Jr., visited a gothic landmark in Europe, but only Junior liked horror movies. (Author’s collection)

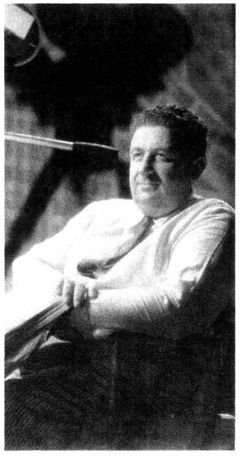

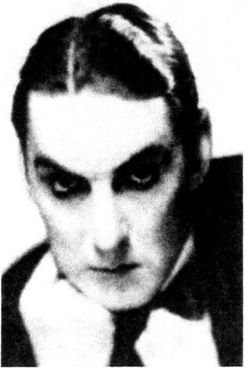

The reclusive Tod Browning produced one of the most obsessive bodies of work in film history. Dracula would be his most famous film, but hardly his best. (Author’s collection)

Browning had a reputation as an alcoholic; his drinking had caused him to be blacklisted in Hollywood for two years in the early ‘20s (he had originally been announced as the director of Chaney’s Hunchback, then pulled from the project). His drunken escapades also engendered a kind of perverse awe among his drinking pals, who

told and retold (and undoubtedly embellished) tales of his inebriated exploits. In one of the most colorful, Browning confronted a stuffy assistant manager at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco during a New Year’s Eve party, who was evidently displeased with the director’s obstreperous demeanor. “As the evening waned, the animosity waxed. Tod yanked out his false teeth—uppers and lowers—and hurled them at the A.M. with the suggestion: ‘Go bite yourself!’”

Browning cultivated a flamboyant persona, favoring loud socks, louder shirts, and the loudest ties. Actress Carroll Borland, who worked for him in 1935’s Mark of the Vampire, recalled that he usually “dressed like he was going to the racetrack.” He was evidently skilled at deflecting attention from his self-sabotaging behavior—he was known to provide his own impromptu sawdust and tinsel on the set, often breaking into song (an a capella rendition of “When the Moon Comes Over the Mountain” was his specialty), sometimes performing a card trick or carny routine.

Unfortunately, any possibility of Browning directing Chaney in Dracula for Universal or anyone else evaporated in June when Chaney’s chronic throat ailment was diagnosed as terminal cancer. The actor who might have been Dracula ultimately choked on his own blood, following a throat hemorrhage on August 26, 1930.

A few days after Chaney’s diagnosis, which was kept from the press, Variety contained the following announcement:

WRAY, THE NECK-BITER

Hollywood, June 21.

John Wray will play the neck

biting monster in “Dracula” for Universal.

Tod Browning will direct.

biting monster in “Dracula” for Universal.

Tod Browning will direct.

Wray, who had played the vicious drill sergeant Himmelstoss in Junior Laemmle’s triumph All Quiet on the Western Front, was an extremely unlikely choice for Dracula, and he was not mentioned again.

It was only the beginning, however, of a silly season in the matter of Dracula casting. Conrad Veidt, the performer originally mentioned by Universal in connection with Dracula, had decided to return to Europe rather than brave talkies in English, in which he was not completely fluent and which he regarded as a professional risk. Although

his accent would not have hampered Dracula in the slightest, he was probably correct to believe his career would be distinctly limited by the coming of sound. Later, of course, his English perfected, he would return to Hollywood as a specialist in wartime villains. But it is clear that a brilliant opportunity was lost when Universal lost Veidt; judging from his many fine silent performances, ranging from the murderous somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to the tragic Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughs, Veidt might well have elevated the role of Dracula to pantheon status.

While Bela Lugosi should have seemed the obvious choice for the part, it was as true in 1930 as it is today that a stage success did not guarantee an actor a chance to play the same role on film. Universal considered a number of actors for the part, foremost among them Ian Keith, a magnetic, classically trained actor with a troubled personal life, whose best-remembered film role would be the alcoholic carny in Nightmare Alley (1946), a part that so eerily reflected the performer’s own circumstances that it is uncomfortable to watch. At the time of Dracula, he had just played a seductive aristocrat in the Universal comedy Boudoir Diplomat (1930), which undoubtedly served as a proximate screen test. Another front-runner was William Courtenay, a distinguished New York actor who had just enjoyed a successful New York run and national tour as a cloaked magician in The Spider. Perhaps the most unusual Dracula of all would have been Paul Muni, mentioned in several accounts as one of Universal’s serious contenders. Muni, who was widely touted as “The New Lon Chaney” after his multifaceted appearance in Seven Faces for William Fox in 1929, insisted repeatedly in print that he had no interest in enacting grotesques, and it is difficult to imagine him actually accepting such a role. At the time of the film’s casting, Muni was appearing on stage at the Pasadena Playhouse in the pre-Broadway run of a split-personality drama, This One Klan, and was certainly within the range of Universal’s viewfinder (in a related bit of inspired casting, Muni was followed at the Pasadena Playhouse by Dracula with the saturnine Victor Jory as the Count and the then-juvenile Robert Young as Harker).

Harold Freedman attempted to exercise some leverage on behalf of yet another performer in negotiations with Universal: “It appears to me that Joseph Schildkraut might be a brilliant piece of casting in

the name part of Dracula,” he wired the studio. “Casting an attractive leading man in this part might be infinitely more effective than putting a character man into it.” Schildkraut may well have been the actor Freedman involved at the last minute to force the sale. Like Max Schreck and Conrad Veidt, Schildkraut had been a Berlin stage actor in Max Reinhardt’s celebrated ensemble, and in the early twenties became a Broadway matinee idol in Molnar’s Liliom.

Bela Lugosi continued to lobby energetically for the role, despite Universal’s expressed lack of enthusiasm; Junior Laemmle had flatly informed the agents by telegram NOT INTERESTED IN BELA LUGOSI PRESENT TIME. Lugosi went so far as to donate his services to Universal’s foreign-language unit, dubbing Conrad Veidt’s role in The Last Performance into Hungarian, and at some point during Universal’s negotiations with Florence Stoker was asked—or took it upon himself—to intercede with Stoker on Universal’s behalf. At the time the sale was closed, Lugosi wired Harold Freedman that he had spent months promoting Universal to Florence Stoker via cables to London, trying to bring down her asking price. Would Freedman please express an opinion to Universal for his being the logical choice for the part?

Ian Keith, seen here as a seductive artistocrat in Universal’s The Boudoir Diplomat (1930), was Lugosi’s stiffest competition for the lead role in Dracula. (Photofest)

Lugosi apparently failed to understand that donating services and acting as an unpaid intermediary in negotiations was putting him in a terrible bargaining position. He didn’t comprehend that expressing enthusiasm for the film in press interviews, and even offering script suggestions (as he did to the Oakland Tribune) giving his own enthusiastic mini-treatment of how Dracula’s sea voyage to England might be translated to the screens, could also be interpreted as a particularly nervy kind of butting in. Lugosi seems to have assumed, with a certain naivete, that magnanimous gestures would be repaid in kind, but the message Universal was receiving was not one he intended. Lugosi was simply proving that he was desperate for the part.

Several years later, he related a somewhat distorted account of the affair to a New York Post reporter, who printed the entire interview in a bizarre phonetic interpretation of a “Hungarian” accent: “De Bram Stoker heirs asked $200,000 for de film reidts, but Universal didn’t like to pay dat much. Zo dey asked me would I correspond wid Mrs. Stoker, de widow, and get it maybe a liddle cheaper. I wreidt and wreidt until I get cramps, and after aboudt two months, Mrs. Stoker says O.K., we can haff it for $60,000. Zo what does Uniwersal do from graddidude? From graddidude dey start to test two dozens fellows for Dragula—but not me! And who was tested? De cousins and brodderin-laws of de Laemmles—all deir pets and the pets of DEIR pets!”

Actually, the search extended considerably beyond Laemmle pets. Indecision over Dracula persisted until just weeks before shooting began, leading E. M. (“Efe”) Asher, Universal’s associate producer now in charge of Dracula, to send the following letter to director Roland West, who had just directed The Bat Whispers (a creepy mystery released by United Artists, with a masked, cloaked title character who would be a direct inspiration for Batman):

Dear Roland,

We will start Dracula in about three weeks. Is there any possibility of getting Chester Morris to play Dracula?

The tough-guy specialist’s role in The Bat Whispers had been a caped villain, after all. And a bat was a bat, wasn’t it?

The director responded:

Dear Efe,

Don’t think I’d care for that part for Chester as we are looking for romance.

Meanwhile, although Louis Bromfield remained the “official” scenarist for several more weeks, screenwriter Garrett Fort (who had just completed work with Browning on the talkie version of Outside the Law, starring Edward G. Robinson in place of Chaney) took out a prominent trade advertisement announcing his assignment to Dracula for “Adaptation and Dialogue.” Bromfield’s enforced collaboration with Dudley Murphy yielded a script that bore almost no connection to Bromfield’s treatment. The means for melding the novel and stage play was now the substitution of Renfield as the real estate agent who travels to Transylvania. (This, of course, left the novel’s leading man, Jonathan Harker, with precious little to do.) Browning took a hand in the script as well, and, under an apparent mandate to save as much money as possible, cut some of the most cinematic sequences, including the climactic chase back to Castle Dracula.

As Universal’s financial situation became even more fragile, and initial enthusiasm for the project waned, the de facto goal was apparently to find a way to film Dracula without having to spend money.

Bromfield, disillusioned and drained by his encounter with Dracula, soon left Hollywood, never to return. Though one of his books, The Rains Came, would enjoy a cinematic success as The Rains of Ranchipur, his attitude toward Hollywood remained sour. “Out of nothing into nothing” is how he summed it up for Life magazine in 1948. Dudley Murphy developed a similarly jaundiced view. He criticized the “misdirected energy” of the Hollywood creative community, “full of people, often brilliant, making compromises. Money and the greed of the place cause them to lose their perspective and gradually lose their integrity. I want to pull out before it’s too late.”

Murphy did pull out, and set himself up as an independent producer, never to return to Hollywood. His most memorable effort would be his landmark production of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, filmed in New York in 1933. Murphy would later relocate his operations to Mexico, where he spent the rest of his life.

The casting process for Dracula had reached a state of total paralysis.

Former actress and Lugosi protégée Carroll Borland had first seen Lugosi in the original touring production at the age of fifteen. “I think all adolescent girls go through a period where they fall in love with horses or monsters or whatever,” she recalled in a 1989 interview. “And I thought that Bela Lugosi was the most exciting person I had ever seen. He was certainly the most magnetic man I have ever known. We would just sit in a room and all the women would go … whoom! And he did the same thing on stage.” The precocious Borland was inspired to compose a full-length novel, an unauthorized sequel to Stoker’s entitled Countess Dracula, which she sent to Lugosi at his Oakland hotel when he made a return stage engagement the following year.

“I wrote all the characters fifty years later, made it modern in the 1930s. I wrote him a letter and asked if he would be interested in seeing it. I don’t know what his education was—I think it was the equivalent of a high school education—but he never read English well, and at that time he didn’t speak it very well, but he understood. He was very impressed that I was going to the university—I went to Berkeley on a Shakespeare scholarship at sixteen—the European concept of the ‘university’ was a much more exclusive one than ours.”

Borland was thrilled when she received an invitation to lunch at the Leamington Hotel, Lugosi’s residence during the stock production of Dracula that Asher, Bromfield, and Murphy had seen. “He invited me—and my mother. Remember, this man was always the European gentleman, observing all the forms and manners and codes and requirements. He decided he wanted to hear the novel, thinking it might have some possibilities as a new stage vehicle to follow up Dracula. So he came to the house in a taxi and stretched out on this very sofa and snapped his fingers for coffee. It took about three days to read it to him.” Borland insisted to the end of her life that Lugosi’s interest in her was professional, albeit “avuncular.” She and her mother had no idea that the Hungarian gentleman stretched out on their sofa had been linked romantically in a scandal as a lover of the “Brooklyn Bonfire” Clara Bow (in company with such other notables as Gary Cooper, and, the tabloids rumored, the entire football team of the University of Southern California). Bow had fallen for Bela after seeing him onstage in Dracula. Twice married before, he had recently embarked on a disastrously impulsive third marriage to an alcoholic San Francisco heiress that was reported to have lasted less than a week.

Lugosi later told Borland that he had contacted the Stoker estate and that their demands were too high. His anxieties about Dracula were at their peak—the film was about to be made, and still, no answer. But he kept his tensions to himself. “He was superstitious and didn’t want to talk about it,” recalled Borland.12 The Hollywood Filmograph , which had editorialized repeatedly in support of Lugosi’s casting, announced that Ian Keith’s casting was virtually a fait accompli. And Lugosi couldn’t have been at all sanguine when Tod Browning (perhaps exasperated at the studio’s indecision) told an interviewer that he was in favor of “getting a stranger from Europe, and not giving his name.”

Finally, in September, Lugosi was offered the part, though the terms of Universal’s contract were grotesque. The studio was offering a flat five hundred dollars a week for a seven-week shooting schedule—in other words, thirty-five hundred dollars for the title role of a major studio film that had been the focus of nearly three years of transatlantic and transcontinental negotiations. It was less than the total money Lugosi had been willing to put up for an option on the film rights. It was a studio power play at its baldest and nastiest. In all his scraping and supplicating the actor had more than tipped his hand, and blown the poker game. Universal knew it could dictate terms, and the Dracula they desired was far too thirsty to put up a fuss.

Bela Lugosi had reached a Faustian crossroads. In accepting the contract, he would almost certainly achieve international fame for a role with which he had spent years in obsessive identification, the role itself a variation on Mephistopheles. But here the roles were reversed, and reversed again, as if in a crazy, cobwebby hall of mirrors—a bargain with the devil represented on both sides. Lugosi had already been stung, by Liveright, for holding out for too much money, and that other actor—almost a boy, that Huntley from England—had been all

too eager to take his place. An actor’s life could always be problematic, even in good times, but this year was one of the worst economically that anyone could remember. And Universal wouldn’t budge.

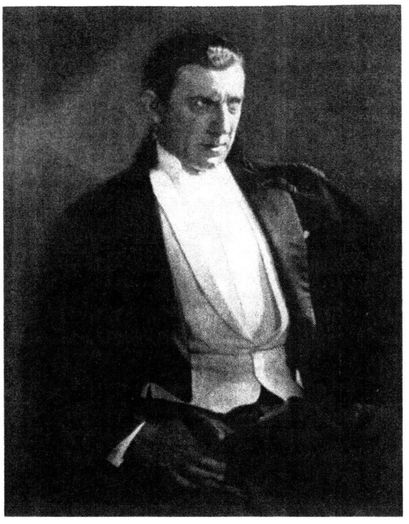

Lugosi in costume for the screen role of his lifetime (Author’s collection)

Lugosi no doubt rationalized. A financial concession, yes, but what an investment! The exposure. The acclaim. The future! Well-meaning friends surely urged him to sign. How could anyone turn down work, these days? And a starring part in a movie by the Laemmles! There were actors on breadlines. He’d be crazy to turn it down. A Universal Super Production. Was there any choice?

On September 11, 1930, Lugosi signed in ink, not realizing he had made a pact in blood.

Filming began on Dracula on September 29, 1930. In addition to

Lugosi’s daredevil last-minute casting, there were still many unresolved problems, not the least of which were the lack of a hero and second female lead.

The lead actress had already been cast. At the age of twenty, Helen Chandler was an immensely popular New York actress, having spent most of her life on stage. She made her debut at the age of eight, her child roles including a stint as the boy prince opposite John Barrymore’s Richard III, and, a few years later, as Ophelia in Horace Liveright’s controversial, modern-dress Hamlet. Tod Browning had seen her opening night performance in the mysterious stage play Silent House, and was no doubt aware of her current appearance in Warner Bros.’ screen adaptation of Sutton Vane’s stage hit Outward Bound, in which Chandler played opposite Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., as a pair of suicides on their way to judgment on a mysterious ship. Viewed today, Outward Bound is an excruciating gabfest of middlebrow metaphysics, but was nonetheless immensely popular as a play and film, a weird prefiguration of Sartre’s No Exit. It certainly served to link Chandler in the public mind with themes of the supernatural. The actress had a fragile, wistful quality that perfectly suited the role of Mina as it was now written—gone completely was any hint of the “New Woman” of the novel; the character was now a complete milksop.

“In Dracula, I played one of those bewildered little girls who go around pale, hollow-eyed and anguished, wondering about things,” she told an interviewer in 1932. What she really was wondering about was how to schedule surgery for chronic appendicitis without holding up the film. She managed to put off surgery until after the film’s completion.

Lew Ayres, who had scored such a hit in Universal’s last blockbuster, All Quiet on the Western Front, originally announced for the role of Jonathan Harker (or what remained of the role of Jonathan Harker), was dropped; in later years he said that the part that really interested him was “the guy who ate the flies and spiders.”

In desperation, Universal turned to RKO star Robert Ames, who at the age of forty-one was probably Hollywood’s oldest employable “juvenile.” (No one seemed to mind that Ames was old enough to be Helen Chandler’s father.) His casting was announced in the October 18 issue of Billboard, but almost simultaneously was eclipsed by front-page news of his messy matrimonial travails and impending divorce—his fourth, and messiest. Ames’s wife, Muriel Oakes, complained in public that Ames was “sulky, bad-tempered and wouldn’t stop drinking.” Ames, she claimed, had been on a marathon bender since they left the altar. Robert Ames suddenly disappeared from any of Universal’s announcements on Dracula. On November 27 of the following year, while engaged to actress Ina Claire, he would be found dead of a hemorrhaged bladder at the Hotel Delmonico in New York, his suite littered with whisky bottles and sedative powders.

The third, and final, Jonathan Harker was to be David Manners, the former Rauf de Ryther Daun Acklom of Halifax, Nova Scotia, a rising young performer brought to Hollywood the year before by director James Whale for the film version of the West End stage success Journey’s End. (Whale, a gifted, idiosyncratic, and finally tragic talent, would create two masterpieces for Universal: Frankenstein in 1931, and its deliriously perverse sequel, Bride of Frankenstein in 1935.) Manners was highly in demand as a specific type of romantic lead, aptly described by Gregory Mank in a 1977 profile: “Hollywood was in the era of the Leading Lady—lacquered goddesses who aimed their best profiles at the camera as their capped teeth gnashed at the scenery (and all too often) the leading man. The dream of these high-heeled deities was to have a romantic screen partner who was handsome without being distractingly sexy, and a polished actor who would not be a scene stealer. Manners was to serve their fantasy.” The fantasy didn’t come cheap; Universal had to pay a fee to Jack Warner for the loan of his contract star, as well as Manners’s two-thousand-dollar-a-week salary—four times the earnings of the film’s nominal star—for an anemic supporting part.

Another latecomer to the cast was Frances Dade, who would play the doomed Lucy Weston (Westenra being too much of a mouthful for the scriptwriters, apparently). Dade, a twenty-one-year-old ingenue from a prominent Philadelphia family, had enjoyed a stage success touring in Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and made her film debut opposite Ronald Coleman in Raffles. The smoky-voiced, blue-eyed blonde could trace her looks to her grandmother, Mrs. Clifford Pemberton, who had been the model for the face on the Liberty dollar. Until the final shooting script, the role of Lucy was somewhat larger and more colorful. Dracula was to first notice Lucy, an accomplished harpist, leaving a London concert hall. Later, he

was to have arrived, uninvited, at one of her private recitals, complimenting her on her fingerwork, though clearly more interested in the possibilities of her neck. The scenes were eventually collapsed into a single sequence, set in a concert hall, with Lucy as an audience member instead of an artist.

As for Renfield, Lew Ayres was right in recognizing the film’s plum role. The part went to New York stage actor Dwight Frye, who had recently moved west with his wife, the actress Laura Bullivant, following the failure of the theatrical tearoom they operated on West Sixty-ninth Street and the general downturn of the theatre economy. Frye’s surviving scrapbooks reveal a performer of remarkable range and popularity; like Helen Chandler, he enjoyed excellent press and was in frequent demand, receiving kudos for his work in Six Characters in Search of an Author and comedies like A Man’s a Man. The role of Renfield, with its shifting moods and explosive outbursts, would be an ideal showcase for Frye’s versatility. He could not anticipate, however, the extent to which the part would limit his Hollywood options. On the strength of Dracula he would attract the attention of James Whale, who cast him as Frankenstein’s demented hunchback … and thus sealed forever the actor’s niche of wild-eyed lunatics and monsters’ assistants.

Edward Van Sloan reprised his stage role as Dr. Van Helsing, along with Herbert Bunston as Dr. Seward. Van Sloan’s screen test consisted of his standing in front of a mantelpiece and mirror, speaking lines from the stage play and ducking when an offscreen “Dracula” smashed the mirror with a vase. The clip was later used as part of the film’s preview trailer (trailers at that time were customarily made from outtakes or specially shot material, since duping original negatives was a cumbersome process). Other supporting players included Michael Visaroff as the innkeeper; Charles Gerrard and Moon Carroll as the comic attendant and maid; Joan Standing, who had withstood the rigors of filming Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, as the English nurse; and, in a memorable cameo, Carl Laemmle’s niece, Carla. Her real name was Rebecca Beth Laemmle, but, like her cousin Julius, she had changed her name in tribute to the studio founder. Five years earlier, Carla had appeared as the prima ballerina in the silent Phantom of the Opera; in Dracula she would have the distinction of speaking the first words of dialogue ever uttered in a talking horror movie:

“Among the rugged peaks that frown down upon the Borgo Pass are found crumbling castles of a bygone age.”

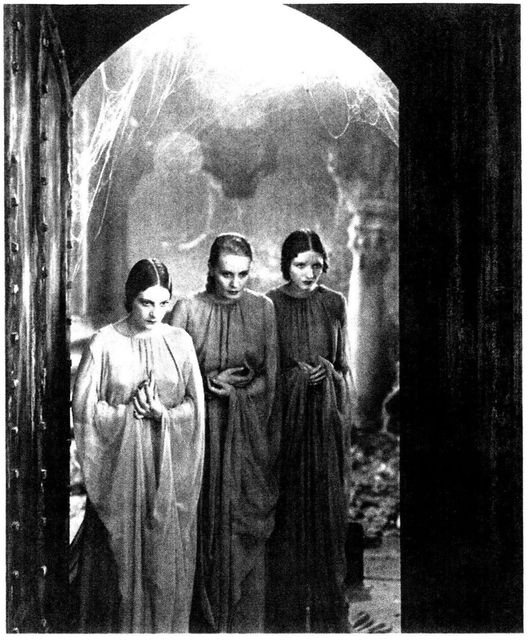

As one of Dracula’s undead brides, Browning cast Greta Garbo’s former stand-in at Metro, Jeraldine Dvorak, reportedly dismissed by Garbo for impersonating her in public. The resulting cameo amounted to a perverse caricature of Garbo’s glacial persona—in essence, “I vant to be alive.” Broadway actress Dorothy Tree—a Hollywood blacklist casualty of the 1950s—made one of her first screen appearances as another of Dracula’s consorts, and the third undead bride was portrayed by Cornelia Thaw, the stage name of Hollywood ingenue Mildred Peirce, shortly to give up her acting career for a more rewarding life as a wife and homemaker. The uncredited speaking role of the flower girl who provides Dracula with his pre-theatre snack was played by Anita Harder, later a beloved fixture of Santa Barbara’s little theatre scene (she played Wilde’s Lady Bracknell there in the 1950s), as well as of that city’s celebrated annual street fiesta. The character actress who memorably plays the Transylvanian innkeeper’s wife has never been identified, although her grandchildren have occasionally been reported to inquire about photos at various Hollywood memorabilia stores. No one, however, seems to have ever made a record of their names.

The supervising art director of Dracula was Charles D. Hall, who had designed Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush and other classic films; in Dracula he also drew upon the talents of designers Hermann Rosse (who had won an Academy Award for The King of Jazz) and the aforementioned John Ivan Hoffman. Several of the sets pushed Universal’s physical capacity to the limits. David Manners recalled that the massive setting for Dracula’s castle, with its huge staircase and eighteen-foot-wide spiderweb “filled the sound stage up to the roof.” In the finished film the height of this set was extended to Westminster-like proportions through the use of a painting on glass mounted in front of the camera. While not credited, the glass shots in Dracula closely resemble the rendering style of Conrad Tritschler, a former stage designer from Britain whom Hall would have known. Tritschler created similar glass effects for the marvelously atmospheric White Zombie, filmed the following year by the Halperin Brothers on the Universal lot and using Universal technicians and sets, including some interiors left over from Dracula. Tritschler died in 1939.

Dracula’s cinematographer, Karl Freund, was not announced to the trade press until filming had already commenced. Browning’s assistant director was Scott Beal (the veteran assistant director, who would have had the most revealing insights of all into the making of Dracula, died in the early 1970s). Symon Gould’s illicit print of Nosferatu had arrived in Los Angeles, and had almost certainly been studied by all the key creative personnel.

The published shooting script for Dracula reveals vividly the extent to which Browning circumvented and undermined the story’s cinematic possibilities. The film was shot roughly in sequence—an odd and inefficient way to work, then as today—and Freund clearly was given some degree of creative latitude with the opening scenes at Castle Dracula during the first days of shooting, when schedules and budget considerations would not have been weighed so heavily. But even these scenes—and they are the core of whatever interest the film retains—are shot in a flat and highly restrictive manner. In scene after scene the script demonstrates just how much Browning cut, trimmed, ignored, and generally sabotaged the screenplay’s visual potentials, insisting on static camera setups, eliminating reaction shots and special effects, and generally taking the lazy way out at every opportunity. In one story that circulated around Hollywood—possibly apocryphal, since it has no firm attribution—Freund became so fed up with Browning’s static ways that he finally just turned on the camera and let it run unattended. Indeed, there is one endless take in the finished film featuring Manners, Chandler, and Van Sloan that runs 251 feet, nearly three minutes without a cut, that was clearly meant to be broken up with close-ups and reaction shots. At one point Chandler tells Manners, “Oh, no—don’t look at me like that,” in an apparent reference to a dramatic change in his expression. The two-shot, however, shows Manners as motionless as a wax dummy—oblivious that the camera is even catching his face.

Freund’s work on Dracula has often been wildly overpraised, as if to enforce a preconceived notion that Freund provides a significant link between German expressionism and the American horror film. Freund was enormously talented, both as a cinematographer and a director—he had worked behind the camera on Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) and with F. W. Murnau on The Last Laugh (1925), and Freund’s directorial work on Mad Love (1935) remains a perfectly

controlled and creepily evocative homage to expressionist horror. In Dracula, however, whatever inspiration Freund might have brought to bear appears to have been effectively hampered by Tod Browning.

Freund made the transition to talkies far more smoothly than Browning, who stubbornly clung to silent working methods. As a silent director, Browning climbed to the top of his profession by dependably delivering crowd-pleasing films under schedule and under budget. But his last picture at MGM, The Thirteenth Chair (1929) was also his first talkie, and was not a success—at least not in comparison with his Chaney films. Like Dracula, it was based on a drawing-room mystery play, and outside of his own performances in vaudeville, Browning had no experience directing dialogue. His difficulties may have been indirectly reflected in one of Universal’s press releases for the film:

A motion picture director—speechless!

Such a condition presents a strange picture to the mind, because directors have always been regarded as somewhat loquacious individuals, who kept up a running fire of suggestions and instructions to the actors during the progress of a scene. But the advent of the talking picture has accomplished the impossible—it has placed the seal of silence on the director.

For while a scene in a sound picture is actually being filmed, there must be absolutely no sounds except those which may properly be heard when the picture is exhibited in a theatre. During the progress of a scene, if it is necessary for the director to indicate the proper time for any particular speech or action, he must do so by motions or by flashing a tiny red light placed well out of sight of the cameras, [and] the sound stage is as hushed and quiet as the grave.

Browning’s preference for the silent screen may actually have improved Dracula in certain ways. He was given co-credit on the shooting script with Garrett Fort for “adaptation and dialogue,” and this fourth and final draft featured dialogue that was judiciously edited and tightened, and would be further pared during production. But Browning’s overall directorial treatment of the material was odd indeed for someone purported to have coveted the project for years. “To be quite honest,” recalled Manners, “Tod Browning was always off to the side somewhere. I remember being directed by Karl Freund, the photographer who came from Germany and had a great sense for film. I believe

that he is the one who is mainly responsible for Dracula being watchable today.” Carroll Borland, who worked with Browning and Lugosi in MGM’s Mark of the Vampire in 1935, found the director equally enigmatic. “I don’t remember him doing a thing. He was this little man who sat there. I was used to stage directors who would take you aside and talk about the character and whatnot, but it was Jimmy Howe [James Wong Howe, the legendary cinematographer] who had much more to do with creating the mood of my scenes. People are always asking me what it was like to work with Tod Browning—and I have to tell them I don’t know!” Lugosi, who had worked with Browning once before, in The Thirteenth Chair for Metro, offered a more sympathetic appraisal of Browning’s position vis-à-vis Universal on Dracula: “The studios were hell-bent on saving money—they even cut rubber erasers in offices in half—everything that Tod Browning wanted to do was queried. Couldn’t it be done cheaper? Wouldn’t it be just as effective if … ? That sort of thing. It was most dispiriting.”

In The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era, film historian Thomas Schatz relates that “Browning was devastated by Chaney’s death, and he never really recovered his professional footing.” Less comfortable with actors who did not direct themselves, Browning seems to have indulged himself in peculiar, nonhuman details. For London After Midnight, he had, for some eccentric reason, been determined to include armadillos as animal bit players, and made special arrangements to have the creatures shipped from Texas. Unfortunately, they had been packed together with live rattlesnakes and arrived in no condition to act. (Their naive handler had apparently wildly overestimated the toughness of their natural armor.) No matter that armadillos were equally out of place in Transylvania as they would have been in London, Browning nonetheless did things his own way, and Bela Lugosi’s momentous first appearance on the huge Castle Dracula staircase would be heralded by a mini-stampede of dasypi novemcincti.

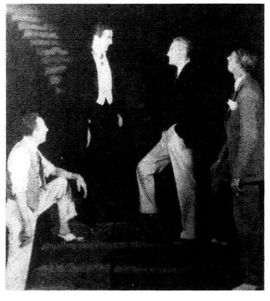

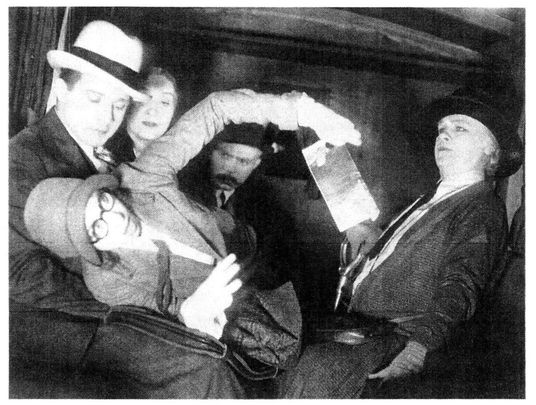

Broken down by Broadway, the stock market crash, and Hollywood, Horace Liveright (facing Lugosi) visited the set of Dracula and posed for publicity photos. At left is director Tod Browning; at right, screenwriter Dudley Murphy. (Author’s collection)

Karl Freund seems to have shown some enthusiasm for Dracula before caving in to Browning’s wet-towel approach. According to the veteran Hollywood model-maker William Davison, the cameraman delivered in person a sketch of a castle he wanted built for the film, which Davison’s shop turned around in twenty-four hours at an approximate cost of two thousand dollars. The five-foot-tall model appears for a few seconds in the finished film—somewhat jarringly in that it bears no similarity whatsoever to the soaring gothic fantasias Charles Hall and company had created for the interiors. It looks, in fact, remarkably like the chateau glimpsed in Nosferatu.

Among the actors, Bela Lugosi remained characteristically aloof from the company. He had already clashed with Universal’s makeup man, Jack Pierce, over the character’s appearance (the script, for example, called for fangs), and insisted on doing his makeup himself. He agreed to wear a hairpiece, however, that added a slight widow’s peak to his somewhat thinning hairline. On the set, David Manners recalled the actor at work: “I mainly remember Lugosi standing in front of a full-length mirror between scenes, intoning ‘I am Dracula.’ He was mysterious and never really said anything to the other members of the cast except good morning when he arrived and good night when he left. He was polite, but always distant.” Lugosi struck Manners as a vain, eccentric performer. “I never thought he was acting, but being the odd man he was.”

Carroll Borland offered another explanation for Lugosi’s reclusive professional behavior, which other actors commented on throughout his career. “He was simply afraid of his English,” said Borland. The old crutch of learning parts phonetically was hampering his ability to interact professionally off-camera. He even dictated all of his correspondence to a secretary, who was responsible for correcting his usage and grammar.

Journalist Lillian Shirley, after visiting Lugosi on the set, reported in the March 1931 issue of Modern Screen that the actor had reached the point of actually hating the part. “I was with him when a telegram arrived. It was from Henry Duffy, the Pacific Coast theatre impresario, who wanted Mr. Lugosi to play Dracula for sixteen weeks,” Shirley wrote. Lugosi threw down the message in disgust, his face visibly reddening, even beneath the gray-green makeup. “‘No! Not at any price … . When I am through with this picture I hope never to hear of Dracula again. I cannot stand it … . I do not intend that it shall possess me. No one knows what I suffer from this role.’” He was certainly suffering financially; a full realization of the inequity of his salary vis-à-vis the other performers’ had no doubt set in.

For its part, Hollywood Filmograph continued to give increasingly overheated accounts of the filming, culminating in the nonsense of October 11: “So horrible is this grotesque monster that everyone on the Big U lot is terrified whenever Bela Lugosi emerges from his dressing room … . Child prodigies scamper into prop rooms … even hardriding cowboys stand at the heads of their trembling steeds.”

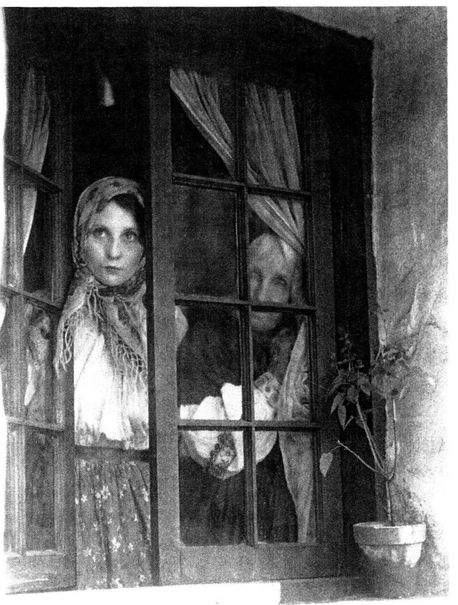

The story, as filmed, contained considerably less blood and thunder. The film opens with a familiar theme from Swan Lake, heard over the titles. The musical passage, arranged and abridged by Universal’s music director Heinz Roemheld, had been routinely used in the silent era as a generic misterioso accompaniment. Except for a brief passage in a concert hall, Dracula, like many early talkies, is often deathly quiet, and many of its pantomimic sequences could have been lifted directly out of a silent film. The agent Renfield is warned that the coach must reach the inn by sundown—it is Walpurgis night, he is told, the evil time of Nosferatu. At the inn, Renfield shocks the local peasants with the news that he must continue traveling after dark for a midnight rendezvous with a carriage sent by a local nobleman, Count Dracula.

At the mention of the name, the peasants cross themselves in shock and beg Renfield to stay. When they realize that he cannot be dissuaded from his journey, the innkeeper’s wife gives him a rosary to wear around his neck, in the hope that it will protect him against the vampires at Dracula’s castle. Renfield’s carriage rumbles off toward the Borgo Pass, and the scene dissolves to the castle and its vaults, where, just as promised, Dracula and his three corpselike wives rise

from their coffins to strike macabre poses. In partial disguise, Dracula is the coachman whom Renfield meets at the Borgo Pass and who drives him to the castle; when the ride proves a bit too bumpy and Renfield leans out the window to beg the driver to slow down, he sees that the horses are being led not by a man but by a huge, flapping bat. The coach pulls into the courtyard of an ancient castle, the driver vanished. Renfield enters the huge, partially ruined, and cobwebfestooned main hall of the castle, where he is greeted on a monumental staircase by a cloaked figure in black carrying a taper. “I am … Dracula,” he announces, with an ambiguous smile. The Count motions Renfield to follow him to the chambers above, where food awaits him, along with a comfortable bed. The details of the lease on Carfax Abbey meet with the Count’s satisfaction. A ship has been chartered to take them to England the following evening. Renfield accidentally cuts his finger on a paper clip, and doesn’t notice the predatory change that comes over his host, or how he is repelled by the rosary he wears. Regaining his poise, Dracula pours only a single glass of wine. “I never drink—wine,” he explains.

The wine, however, is drugged, and Renfield collapses in front of a window while a bat flaps mockingly in his face. The three weird women from the vaults approach him with a strange, gliding motion, only to be repelled by the returning Dracula, who claims the young man’s blood as his own. The scene dissolves to a storm at sea, and the hold of a ship where Dracula’s earth-box is being protected by Renfield, now a raving madman. Dracula rises, and Renfield begs him for “lives, small ones, with blood in them” when they arrive in England. Dracula magisterially ignores his slave, and focuses his attention instead on the stock footage of sailors battling the storm. The scene fades, and we next hear the voices of the men who have boarded the derelict vessel that has drifted into Whitby Harbor, all its crewmen dead, the captain lashed to the wheel. The only survivor is a lunatic with a bizarre craving to devour flies and spiders. Renfield is committed to a local mental hospital, the Seward Sanitarium.

Meanwhile, Dracula moves freely about London, blending inconspicuously with his cloak and evening clothes among the elegant, theatregoing crowds. A flower girl on a side street offers him a buttonhole, but gives the vampire her life instead. Refreshed from his snack, Dracula moves on to a concert hall, where he contrives an introduction at

the box of Dr. Seward, owner of the sanitarium which adjoins the grounds of Carfax Abbey. Seward presents his daughter, Mina, her fiancé, John Harker, and Mina’s attractive friend, Lucy. Lucy is immediately fascinated by the Count, and he by her. Later that night, he enters her bedroom window in bat-form and bestows his fatal kiss.

From this point on, the film falls back on the style and conventions of the stage play. Mina begins to have bad dreams, and believes that Lucy has returned from the dead. Dracula has insinuated himself into the Seward household as a frequent guest whom Mina welcomes but whom Harker resents. Dr. Van Helsing, a colleague of Dr. Seward’s, suspects a vampire and quickly exposes the Count by confronting him with a mirrored cigarette box, in which he does not reflect. Dracula smashes the box. “For one who has lived not even a single lifetime, you are a wise man, Van Helsing,” he sneers, recognizing his match. With Renfield’s assistance, Dracula continues to drain Mina’s blood, and finally abducts her to Carfax Abbey to complete her transformation into his vampire bride. The men follow, and Dracula, thinking that Renfield has betrayed him, strangles the lunatic and escapes with Mina into the Carfax vaults. The sun rises, Dracula’s coffin is discovered, and he is perfunctorily staked, offscreen. Mina’s trance lifts, the lovers are reunited, and the film ends—or seems to. Halfway through the end title of the film during its original release, Dr. Van Helsing appeared on-screen, standing against the proscenium of a motion picture theatre, and delivered the verbatim epilogue from the stage play: “Just a moment, ladies and gentlemen! Just a word before you go. We hope the memories of Dracula and Renfield won’t give you bad dreams, so just a word of reassurance. When you get home tonight and the lights have been turned out and you are afraid to look behind the curtains and you dread to see a face appear at the window—why, just pull yourself together and remember that after all there are such things.”

Dracula finished principal photography November 15, 1930, six days over schedule but almost fourteen thousand dollars under budget. Some additional scenes and retakes were shot in December and January. The editing process may have further truncated the story. One entire, expensive set—a secondary staircase and hall in Carfax Abbey—was simply not used in the film, though scene stills indicate that footage was shot. The whole subplot involving the discovery and de-struction

of Lucy as a vampire is simply dropped in midfilm and never resolved. A beautful glass shot of Carfax Abbey overlooking the crashing sea was similarly not used. Renfield is shown attacking the maid, yet she turns up hale and unharmed a few minutes later. For some reason—revenge by Freund on an inattentive director?—a large, ragged piece of cardboard apparently used to reduce the glare of a practical lamp in Mina’s bedroom is fully visible to the camera in two shots—in one, it occupies almost a quarter of the screen, in the foreground, as Dracula makes his approach. Dracula’s demise was reduced to a series of offscreen groans. And there would be problems to come. The finished titles, as transcribed in the cutting continuity dated at the beginning of February, made no mention of Hamilton Deane or John L. Balderston. They did, however, give Lugosi a solo billing under the title. Balderston’s correspondence file on this matter has not survived, but it seems obvious that an objection was raised citing the terms of the contract. Universal would have been forced to remake the main titles at the last moment, reinstating the playwrights and relegating Lugosi to the third-title cast list. There is some tangible indication of the credits being assembled hurriedly—Carl Laemmle’s title is actually misspelled as PRESIENT.

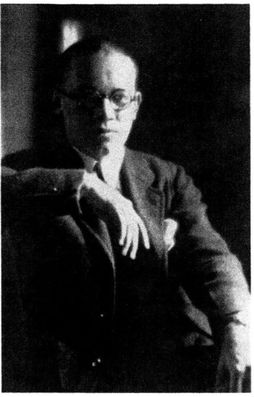

Screenwriter Garrett Fort (Billy Rose Theatre Collection, The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center; The Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

According to one published account, Laemmle, Sr., had “violent heebie-jeebies” over the finished picture when it was screened for him. In The Genius of the System, film historian Thomas Schatz reports that a November 1930 preview took place, and this may account for the two running times that have been persistently cited for the film—eighty-four minutes versus the actual running time of seventy-five minutes. Laemmle may well have demanded cuts in order to increase the film’s funereal pace, which would explain the missing scenes, continuity problems, and discrepancies of running time. The final negative cost of Dracula, not including exploitation, was $441,984.90.

The world premiere of Dracula was set for Friday, February 13, at the country’s unofficial cathedral of the motion picture, the Roxy Theatre in New York. The ball was now squarely in the court of Paul Gulick, Universal’s head of promotion in New York. He had already placed a number of lurid trade ads in Variety, Motion Picture Herald, and elsewhere featuring an artist’s conception of Bela Lugosi, eyes glowing and hairpiece blowing as he leaned over a sleeping woman with prominent nipples. The same breasts would also be given play on the cover of a tie-in edition of the novel, to be published by Grosset and Dunlap, no matter that the actual women in the film were corseted to the throat. Ballyhoo was ballyhoo. Anyway, no one knew what kind of picture this was. A horror story? A love story? Was it going to be bats or beds … or a little of both?

David Manners and Helen Chandler provided Dracula’s supposed love interest. (Author’s collection)

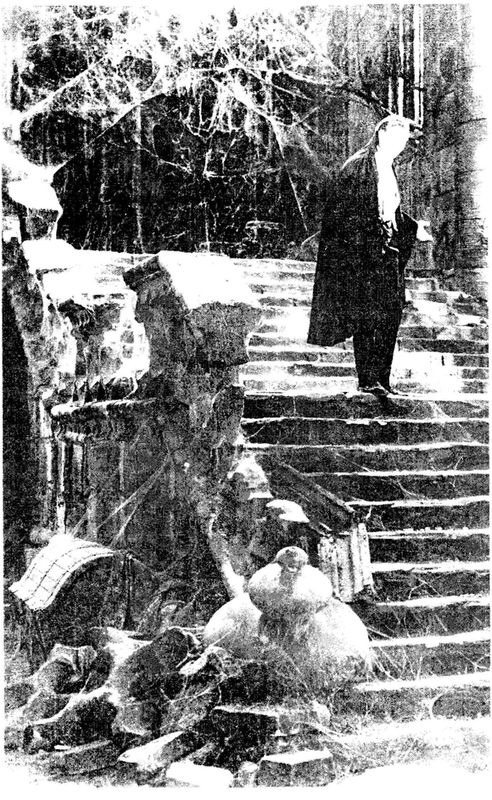

Upstairs/downstairs: Dracula invites his guest to partake of vampiric knowledge in the chambers above. (Author’s collection)

Joe Weil, head of Universal’s exploitation department, arranged to have the island of Manhattan “sniped” with teaser advertisements printed in dripping red letters: GOOD TO THE LAST GASP—DRACULA ROXY THEATRE and I’LL BE ON YOUR NECK FRIDAY THE 13TH—DRACULA. Department stores sported lavish window displays of the photoplay edition of the novel surrounded by photos and window card posters (these advertising graphics, so liberally distributed—and discarded—at the time of the film’s release, can today fetch as much as ten thousand dollars apiece from die-hard collectors). Contrary to many previous accounts of the film’s release, Universal planned Dracula as a Friday the 13th tie-in, and completely ignored the possibilities of Friday the 13th, 1931, falling next to Valentine’s Day. On February 11, an ad was taken out in The New York Times featuring the leering face of Bela Lugosi behind a fake telegram to S. L. “Roxy” Rothaphel: DEAR ROXY DONT BLAME ME BUT I WAS BORN SUPERSTITIOUS STOP JUST HEARD YOU ARE OPENING DRACULA FRIDAY STOP THAT BAD ENOUGH BUT FRIDAY THE THIRTEENTH IS TERRIBLE STOP I HAVE PUT EVERYTHING I HAVE INTO THIS PICTURE AND AS A FAVOR TO ME CAN’T YOU OPEN YOUR PRESENTATION THURSDAY STOP BEST REGARDS TOD BROWNING.

And Universal’s Dracula was released to a trembling world on February 12, 1931. It was a world that trembled for a number of other reasons than for fear of the un-dead. Throughout most of 1930, the country had been in a trancelike state of denial about the economy—a general awareness of the Depression’s reality dawned only gradually. The public’s entertainment tastes were becoming increasingly stylized and escapist; Radio City Music Hall, then under construction, reflected this impulse vividly, as did the nationwide mania for miniature golf, which even film exhibitors viewed as a threat.

Dracula’s trajectory as a film encompassed and reflected both the precrash days of dizzying optimism, and the bottomless pit of economic stagnation. The film can be read as an unconscious allegory of encroaching, paralyzing force, not unlike the Depression itself. The film

becomes paralyzed, numb, and static, enervating both to the viewer and the performers. When Bela Lugosi draws his black cape over sleeping jazz baby Frances Dade—the image of the Liberty dollar, according to her publicity—he is performing a rite of economic extreme unction. (Soon after Dracula, Lugosi appeared in a humorous short subject that made the same point even more sharply: approaching the quintessential flapper icon Mae “Betty Boop” Questal, he informs her that “you have booped your last boop” and summarily sinks in his fangs.)

Dwight Frye’s performance as the fly-eating maniac Renfield was so definitive and convincing that it hindered the versatile actor’s future opportunities in Hollywood. (Author’s collection)

Dracula has always been a lightning rod for prevailing social anxieties. In the absence of a strong director, the film would become even more susceptible to the half-conscious projections of its creators, its public, and its critics. Dracula would provide a particular social catharsis for the moviegoing public of 1931. But that would be far from the limit of its appeal.

The film’s first two reels are without question its strongest, and provide the main reason for the film’s enduring fascination. The Transylvania sequences have, however, been routinely overpraised in terms of their direction and cinematography. Browning’s direction is heavy-handed as usual and Freund’s camerawork shines only in relation

to the mediocrity of the balance of the film. What, then, brings commentators back again and again to these scenes, trying to capture validity or meaning?

Tod Browning’s unholy three. At left is Dorothy Tree, a noted stage actress who made her first unbilled film appearance as one of Dracula’s consorts. A victim of the Hollywood blacklists, her film career was cut short in the early 1950s. In the center is Jeraldine Dvorak, former stand-in for Greta Garbo, who found it difficult to escape Garbo’s shadow and establish her own screen persona. Dismissed by Garbo, she found refuge in the vaults of Dracula and was subsequently cast by Karl Freund in his 1933 Universal comedy, Moonlight and Pretzels. At right is Cornelia Thaw (real name: Mildred Peirce), a Hollywood ingenue who shortly thereafter gave up her acting career for a more satisfying life as a wife and homemaker. But her son recalled that the family always tuned in to Dracula whenever it was shown on television. (Author’s collection)

Cinematographer Karl Freund, a Prussian taskmaster in the tradition of Stroheim, whose efforts on Dracula may have extended far beyond the camera (Photofest)

Part of the explanation must lie in the rather extraordinary number and layers of visual symbols. Renfield’s visit to Castle Dracula is densely packed with evocative visual cues: the high gothic architecture is unmistakably ecclesiastical—Castle Dracula is religion in ruins. Dracula meets the traveler on a huge staircase, a figure of illumination with a tapering candle, and guides him to a higher level. A huge spiraling spiderweb—an ancient symbol for the fabric of reality—is a barrier that must be crossed. An unholy trinity of bats is observed. The castle’s vaults, the audience already knows, are places of death and resurrection. Above, the young man is conducted to an altarlike table and offered a chalice. There is talk of wine and blood, and secret understandings. The power of the crucifix is demonstrated. Three silent women who approach are banished, and a male-to-male blood ritual is performed.

The religio-mythic trappings, the initiation/corruption of an in-nocent,

the evocation of a Grail quest that culminates in a blood sacrifice and homoerotic rite of passage are all motifs powerful enough in and of themselves, but brought together within a space of ten minutes they achieve a kind of psychological critical mass unprecedented in the cinema. Exactly why Tod Browning decided to have Dracula attack Renfield is unclear—the script called for the vampire women to do the deed—but consciously or unconsciously he tapped directly into Stoker’s subtext, and the film takes on a decidedly homoerotic tone. Renfield is the only character in the film who actually undergoes any change or development; the real “story” is Renfield’s tragic, unrequited love for the Count.

Transylvanian peasants are less than pleased at the prospect of nightfall. (Author’s collection)

The press reaction to Dracula was mixed at best. The trade papers, especially those based on the West Coast, were much more candid in their appraisals than the general readership dailies, many of which seemed to be acting as pipelines for Universal’s publicity office. Norbert Lusk, reviewing the New York premiere for the Los Angeles Times on February 22, commented that, “in spite of pronounced merit, the story of human vampires who feast on the blood of living victims is too extreme to provide entertainment that causes word-of-mouth advertising. Plainly a freak picture, it must be accepted as a curiosity devoid of the important element of sympathy that causes the widest appeal.” Hollywood Filmograph, which had lobbied so energetically for Lugosi’s casting, did not preview the film and made no appraisal at all until after Dracula’s West Coast release at the end of March. Universal in the interim took out trade ads with puff quotes from the New York dailies. The Filmograph’s reviewer, Harold Weight, pulled few punches. “Tod Browning directed—although we cannot believe that the same man was responsible for both the first and latter parts of the picture,” he wrote. “Had the rest of the picture lived up to the first sequence in the ruined castle in Transylvania, ‘Dracula’ … would have been a horror and thrill classic long remembered.” Predictably, at least one reviewer took the totally perverse stance that it was the opening sequences that lagged, but that Browning had redeemed himself with the second part of the film.

Carla Laemmle (left) uttered the first line of dialogue in a supernatural horror talkie. Seventy-two years later, she would still be signing photos and answering fan mail. (Author’s collection)

Variety reported that Dracula grossed $112,000 in its inaugural engagement at the Roxy (though Universal claimed a higher figure in its trade ads). The earnings were, in any case, quite respectable but not a sellout, and the Roxy dropped Dracula after eight days. At this point no one at Universal dreamed the film would be its top money-maker of the year. The picture went into national distribution during March. At the New Haven opening, Yale students let loose a flock of bats they had smuggled into the theatre. The audience thought the stunt was a publicity gag, and complimented the management. In San Francisco, “Midnight Whoopee Shows” were scheduled. And so on.

To cover all possible venues, Universal had prepared a silent version of the film with dialogue titles for theatres, especially those in small towns, not yet wired for sound. The version was nearly identical to the talkie, save for the condensed dialogue and the inclusion of a brief shot, from a distance, of Van Helsing pounding the stake into Dracula’s heart—an offscreen groan being a clear impossibility in a silent picture. For European engagements, this version would have been accompanied by a continuous recorded musical score, in all likelihood drawn from classical scores in the public domain. By the time Dracula reached Los Angeles, Universal was in the middle of a work shutdown, yet another austerity measure. None of the usual display advertising was taken out in the Los Angeles Times when the film opened at the Orpheum, recalled the late Lillian Lugosi Donlevy, Bela’s fourth wife: “It really wasn’t a big deal. No ballyhoo, no nothing!” In the Times local review, Philip K. Scheuer was hardly sanguine: “Bram Stoker’s classic of a generation [ago], Dracula, is now an audible movie, and you may hear and see it at the Orpheum if you are so minded.” Scheuer politely praised several elements, but called the film “a somewhat less than grisly affair.” Coincidentally, the same page of the paper contained a brief notice that Tod Browning was leaving Universal, having completed his contract, and would shortly return to Metro.

The best scenes were saved for staircases. Here, Renfield realizes, too late, that Dracula’s designs no longer require the services of an insect-eating slave. (Photofest)

Advertising herald for Dracula (Author’s collection)

Dracula outperformed almost everyone’s expectations, and certainly vindicated Carl Laemmle, Jr., in the eyes of his many critics. Morbid or not, talking horror films were a new and evidently prof itable genre. Next on Laemmle’s list would be Frankenstein, based on a John Balderston adaptation of a play by Peggy Webling that Hamilton Deane had produced in England. Horace Liveright had announced it for Broadway, but had been unable to raise the capital. With appropriate hubris, he dreamed of personally directing a film version of the “Modern Prometheus,” a proposition that horrified everyone concerned.

Liveright’s efforts in Hollywood had produced very little; he was drinking heavily (as he always had) and was about to embark on his final, downhill slide. Ironically, Liveright had been directly responsible for bringing both Dracula and Frankenstein to Hollywood’s

attention. The two properties would spin more money for others than Liveright had ever dreamed of at the height of his own career. But Liveright, like his discovery Bela Lugosi, would never share in the windfall. In October 1931, just as the film would begin production, Liveright lost even his stage interests. Florence Stoker and the playwrights moved against the producer for chronic nonpayment of royalties, and the stage rights were recontracted to Alfred Wallerstein, who assumed Liveright’s debt. Liveright had grossed over $2 million on Dracula, but finally lost the property over the paltry delinquent sum of $678.01.

Wallerstein was nothing if not resourceful in wringing the last drop of blood from the legitimate stage Dracula, and mounted a final touring production in 1930–1931 capitalizing on the film publicity. Wallerstein’s vampire was Courtney White, a brooding thespian who, at least according to one review, jettisoned Liveright’s green makeup for an unforgettable countenance of bilious yellow. The jaundiced Count’s leading lady was Marcella Gaudell, who later told her son, the actor Robert Vaughn, that White was “an absolute madman, who behaved as if he really thought he was Count Dracula.”

Courtney White: “an absolute madman” as Dracula, according to his leading lady (Author’s collection)

Edward Van Sloan and Bela Lugosi reprise the classic standoff they perfected on stage. (Photofest)

By the end of fiscal 1931, on the strength of Dracula, it was clear that Universal would make a profit for the first time in two years. In its first domestic release the film would gross almost $700,000, nearly double its investment. World receipts by 1936 were $1,012,189.42 Although financial problems would continue to dog Universal throughout the 1930s, it is generally acknowledged that the bright year of 1931 prevented the studio from folding, and that Dracula had much to do with stabilizing Universal’s fortunes.

As should be abundantly clear, Dracula was a far from satisfactory film from an artistic standpoint. Almost everything about its production and direction had been seriously compromised or undermined. And no doubt, there were those who wished it could have all been done over again in a way that did justice to the possibilities of the material.

It was, therefore, in the best tradition of Hollywood wish fulfillment, that that is exactly what happened.

Premiere of Dracula at the Roxy Theatre, New York (Free Library of Philadelphia Theatre Collection)