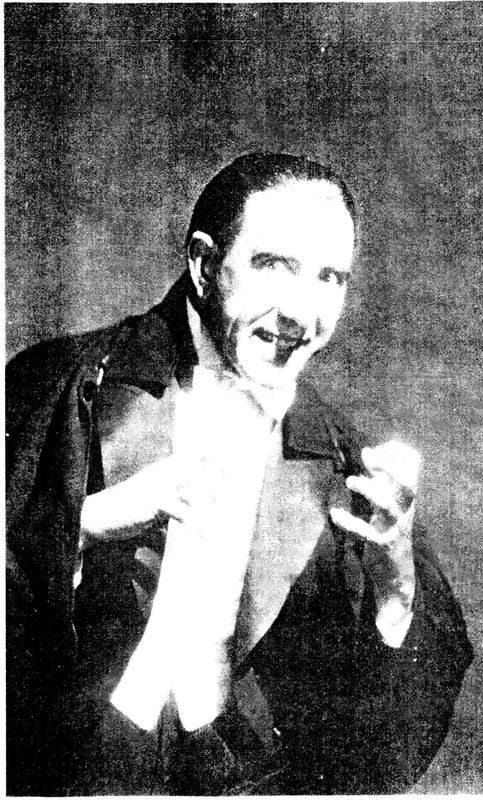

Carlos Villarias, the hot-blooded Spanish Dracula, shadowed Bela Lugosi after midnight for an ambitious reinterpretation of the 1931 American flim. (Courtesy of Ronald V. Borst / Hollywood Movie Posters)

“LA SANGRE ES LA VIDA”

The Romance of the Spanish Dracula

In which we discover Hollywood, in transition and translation, where

a bright young man sleeps by day and works by night,

uses cobwebs to catch a wife, and does better by the Count than

the others, in a tongue he does not naturally speak.

a bright young man sleeps by day and works by night,

uses cobwebs to catch a wife, and does better by the Count than

the others, in a tongue he does not naturally speak.

LUPITA TOVAR WAS VERY FRIGHTENED.

It would prove to be good practice.

The seventeen-year-old aspiring actress from Mexico clutched a letter in English, which she could not read—a letter of introduction to Universal Pictures from Fox Films, where she had done some bit parts in silent pictures. Tovar had won a talent competition as a schoolgirl in Mexico and had come to Hollywood with her grandmother the previous year, but now the spectre of talking pictures was threatening to dash her hopes. In the silent days, film had been a truly international medium. Now, Fox was bringing English-speaking actors from New York, and her contract was not to be renewed.

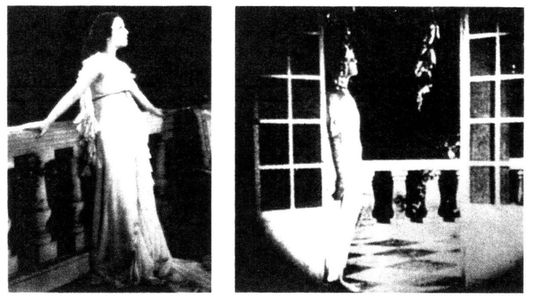

Lupita Tovar in the Spanish version of The Cat Creeps (1930). Paul Kohner’s foreign-language adaptation was so atmospherically realized that Carl Laemmle, Sr., ordered the American film to be reshot in the same manner. (Author’s collection)

The ingenue waited nervously. The producer Tovar was scheduled to see had not arrived. She was told he was in a meeting. But as she sat in the bungalow-style office on the Universal lot, a tall man with a penetrating gaze passed through the room again and again. Watching. Looking.

Unnerved by the silent, menacing attention, Tovar left her letter of introduction and went home.

A message was waiting for her when she arrived. It was the producer. He was sorry his meeting had gone on so long, but would she mind coming back? The letter from Fox had been extremely complimentary.

Tovar hesitated. She didn’t want to subject herself to any more ocular advances from that strange man. “I went to my dancing teacher, Eduardo Cansino, the father of Rita Hayworth. Rita was a little girl

then, and Cansino and his wife were terribly nice to me. I told them what had happened at Universal and that I was afraid to go back alone. All right, they said, we’ll take you. But when we finally got to meet the producer, Paul Kohner—it was the man who had been staring at me!”

At the age of twenty-seven, Paul Kohner was an ambitious young presence at Universal. Born in Czechoslovakia and educated in Vienna, Kohner had risen through the Universal ranks as office boy, publicist, and personal assistant to Carl Laemmle, Sr. As a production supervisor, he had been responsible for Paul Leni’s lush costume spectacle The Man Who Laughs (1928), with Conrad Veidt. In many ways, Laemmle treated Kohner like a son—with all the complexities and ambivalences built into a family relationship. In reality, Kohner felt himself to be the low man on the Universal totem pole. Though he had worked for Laemmle for years, he had no formal contract and had never asked for one. “My salary is puny compared to those in other studios. But I cannot demand more money, nor do I dare to quit,” he confided to his brother and biographer, Frederick Kohner.”I probably couldn’t get a job anywhere else because everyone around Hollywood believes that I’m a nephew of the Old Man.” Kohner wasn’t, but nepotism at Universal was a standing joke in the industry and beyond (Ogden Nash was inspired, memorably, to comment on the situation in verse, rhyming “Laemmle” with “faemmle”). Not only did the payroll swell with Laemmles, but the studio went so far as to house selected relatives in bungalows on the lot.

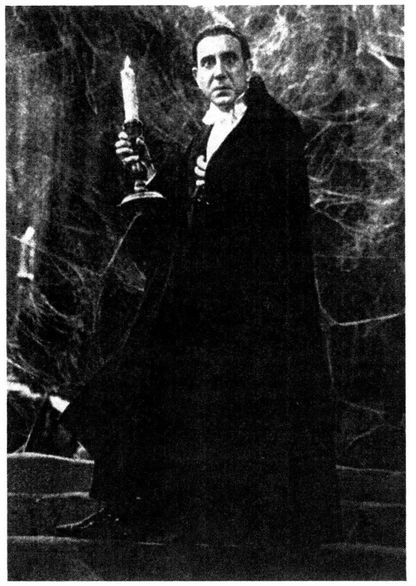

“Yo nunca bebo … vino.” El Conde Dracula (Carlos Villarias) serves Renfield (Pablo Alvarez Rubio) some Spanish wine of unexpected potency. (Author’s collection)

Kohner had achieved his position through hard work. However, with the rise of Junior Laemmle to head of production in 1928, Kohner’s niche became less secure. Junior was distinctly less interested in European properties, talent, and directors, which were Kohner’s strong suit, if not his passion. “Junior’s running this joint now,” said one director, “and if there’s one thing the kid can’t stand, it’s ‘great’ European producers and directors.”

One German director Universal had imported was Paul Leni, whose work in Europe had included the expressionist classic Waxworks. For Universal he directed the highly stylized and atmospheric old-house chiller The Cat and the Canary, adapted from the long-running mystery play about an eccentric who makes his heirs wait twenty years for the reading of his will, with tensions escalating commensurately. Cat was followed by The Man Who Laughs starring Conrad Veidt as Victor Hugo’s tragic grotesque Gwynplaine, whose face was carved into a permanent grin in childhood. The film had probably been planned for Lon Chaney before his decision to return to Metro after The Phantom of the Opera. Kohner had been the production supervisor for The Man Who Laughs and was responsible in no small part for the film’s sumptuous look and meticulous execution. Leni was single-handedly creating a new style, moody and macabre, and was Universal’s resident horror specialist at the time the studio leaked its bogus story about acquiring the rights to Dracula, with Veidt as the film’s probable star. If Veidt and Leni were involved in Dracula, it is inconceivable that Paul Kohner was not also involved, perhaps leaking the trade paper story himself in an attempt to get Dracula on the Big U’s front burner.

The project came to nothing, however, with the untimely death of Paul Leni by blood poisoning in 1929.

Lupita Tovar was genuinely frightened by the possibility that talkies might end her career in Hollywood. (Author’s collection)

Following Leni’s death, Kohner’s recommendations to Junior for projects went unanswered. Finally, in frustration, Kohner went directly to his “Uncle Carl” with a proposition.

During the silent era, Universal had earned half its revenues from foreign countries. Talking pictures posed a severe threat to this market. Dubbing was not yet practical; ordinary sound recording and synchronization presented problems enough. Moreover, much of the attraction and novelty of talking pictures derived from hearing actors speak in their natural voices. The international film markets were in chaos over talkies. Some countries were proposing embargos and punitive tariffs if quotas of films in their own languages were not met. Some commentators even lobbied in print for Esperanto as “the new universal language of film.”

Kohner suggested, more realistically, that Universal follow the lead of other studios, and begin producing simultaneous foreign-language versions of its domestic talkies. These versions could be produced at a

small fraction of the original costs—from forty to seventy thousand dollars—owing largely to the costs saved on new sets and cheaper foreign talent.

Uncle Carl was impressed, and immediately named Kohner head of foreign production, at a salary raise of twenty-five dollars a week. Laemmle was puzzled, though, at how Kohner planned to handle his daytime duties and supervise the foreign-language films, which he intended to shoot at night, after the American units had left for the day. “You have to sleep, Kohner—how can you do it?” asked Uncle Carl. “Oh, I know how to do it,” the ambitious young man replied. “I can sleep between shifts on a couch in my office.”

The first project was to be a Spanish-language adaptation of Rupert Julian’s The Cat Creeps, a sound remake of Leni’s mystery melodrama The Cat and the Canary, made by Universal in 1927. Kohner was confident of his logistics. What he needed now was a Spanish-speaking star.

Lupita Tovar struck him immediately as a personality of extraordinary possibilities. She was astonishingly photogenic, and totally unaffected—a truly ingenuous ingenue. But even with Eduardo and Volga Cansino standing by as bodyguards, Tovar mistrusted the producer. She held tight to her resume photos. Kohner asked if he might keep one. “They’re for business!” Tovar snapped. “I mean for business,” replied Kohner. “And I’d like your telephone number, too.” He offered to take them to dinner, but, to Tovar’s relief, the Cansinos demurred.

The next day they returned to view some of her work from Fox. “You could tell he was looking at me and not the screen,” Tovar recalled. “Well,” said Kohner. “You photograph well. Now how about dinner?” They refused again, invoking Tovar’s grandmother. They would need permission. Kohner called the grandmother. “Hello, Mrs. Sullivan? This is Paul Kohner at Universal Pictures. With your permission, I’d like to take your granddaughter to dinner.” Mrs. Sullivan’s only objection was that Tovar had not taken a coat. Kohner promised she would not get cold.

Tovar was terrified. She took the phone and talked to her grandmother in Spanish. “Grandma! What have you done?”

“Oh, he sounds like a very nice person. It’s all right.”

Kohner took her to dinner at the Universal commissary.

“There was a whole bunch grouped there,” Tovar recalled, “these

young directors William Wyler, Ernst Laemmle, Kurt Neumann—and I was the only girl. And they were all talking in German among themselves—about me! Apparently they hadn’t approved of his previous girlfriend, but they did approve of me.” Kohner had earlier broken an engagement to Mary Philbin, the ingenue who tore the mask from Lon Chaney’s face in The Phantom of the Opera.

Kohner paid Tovar twenty-five dollars a night to film Spanish introductory sequences for Universal’s musical variety extravaganza The King of Jazz. Tovar decided there was no money in films and prepared to return to Mexico. Kohner convinced Laemmle to give her a contract. On the basis of Kohner’s enthusiasm, she was cast as the female lead in The Cat Creeps without a screen test.

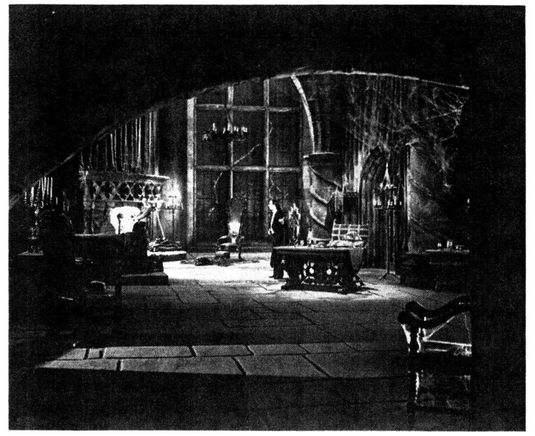

The Cat Creeps—to be known as La Voluntad del Muerto in Spanish—gave Paul Kohner the heady opportunity to second-guess artistic decisions of the English-language unit, which he did with great gusto. Finding Rupert Julian’s daily rushes to be lacking in atmosphere, he completely re-dressed and relit the sets à la Leni, making extensive use of candles, cobwebs, and shadows. “The result was very eerie,” recalled Tovar. Laemmle was so impressed with the foreign version that he ordered the English material to be reshot, with Kohner acting as artistic advisor. Unfortunately, neither version of the film has survived, though scene stills give some indication of the drama and chiaroscuro of Kohner’s mise-en-scène.

Tovar, whose English was nearly nonexistent at the time, was fairly well-shielded from the obvious political nuances of the situation. “All I knew in English was how to say ‘No,’” Tovar recalled. “The first night on the set, everyone went to dinner, but I didn’t know that, and just sat waiting for them to come back. Paul came over to me. ‘Aren’t you hungry?’ he asked. ‘No, thank you.’ ‘Well, come on anyway,’ he said. He tried to get me to order something but I was embarrassed. I just had coffee. I didn’t know the tickets we had been given were for free meals, and I didn’t have the money to pay.”

Tovar soon got used to the regular free meals, but the public attention that came with the job remained unsettling. She still thought of herself as a schoolgirl, not a movie star. La Voluntad del Muerto was a sensation in Mexico, and one of Tovar’s public appearances there nearly created a riot. She had to be lifted out of the mob atop a police car.

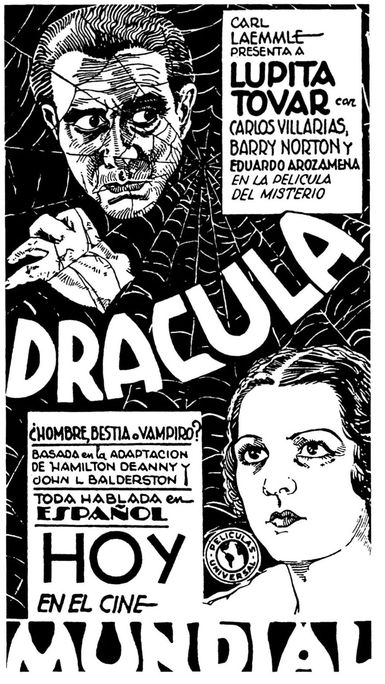

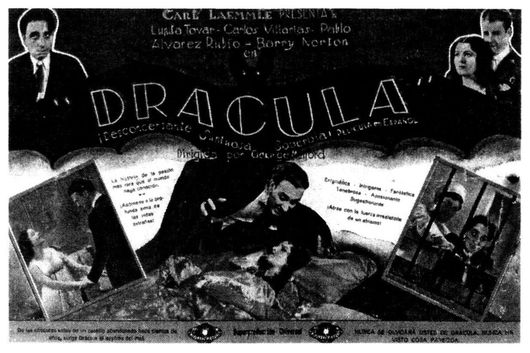

Advertisement for the Spanish Dracula during its Mexico City engagement (Author’s collection)

Throughout the film’s production and promotion, Kohner had bombarded her almost daily with flowers and candies. At the Mexico City premiere, telephonic speakers were set up in the theatre to convey live congratulations from Carl Laemmle, Sr., and stars like Ramon Novarro. Kohner couldn’t help but dominate much of the long-distance

chatter himself. Laemmle kidded him about it “on air.” What was his interest in this starlet, anyway? “I just want to encourage her,” Kohner replied.

Following La Voluntad del Muerto, Tovar’s family gave her an ultimatum. “My father said, All right, you have proven you can do something—now come back to the family and back to school.” Kohner was not about to lose her so easily. Universal’s legal department informed Tovar’s father that they were exercising their contract option on his daughter. Her next picture would be a Spanish-language version of Dracula.

Kohner’s treatment of Dracula was nothing if not ambitious, and today can be read as an almost shot-by-shot scathing critique of the Browning version. And whatever else it is, the Spanish Dracula remains one of the few examples in world cinema of a simultaneous, alternate rendition of a familiar classic, richly illustrating the interpretive possibilities of a single script.

Kohner’s director for Dracula was George Melford, well-known for his work on Westerns and perhaps best remembered as the director of Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik. Melford did not speak Spanish, but gave instructions through an on-set interpreter, or “dialogue director,” named E. Tovar Avalos. Cinematographer George Robinson brought a sophisticated visual sensibility to the assignment, employing a highly mobile camera, complex compositions, and deep shadows. He would later shoot many of Universal’s most memorable horror classics, including all the Dracula follow-ups, from Dracula’s Daughter through House of Dracula.

Kohner, Melford, and Robinson worked as a closely knit team, Tovar recalled, each taking turns peering through the viewfinder. She remembered Kohner as a meticulous perfectionist during Dracula, “determined to improve everything.” Indeed, the degree to which the team felt it necessary to rework the American film bordered on the obsessive. If Browning and Freund composed a shot from right to left, the Spanish film would reverse it, as if by reflex. The American compositions are remarkably flat, like a play performed on a narrow stage apron. Robinson’s camera work is distinguished by its use of multiple planes of focus and action. Foreground objects create tension and depth, while middle-ground devices (cobwebs, windows, branches, bars, etc.) further split and define the visual field.

His work is especially flattering to Charles D. Hall’s sets; the angles use the decor for inspiration rather than cropping it arbitrarily. Much of the traditional criticism of Dracula has blamed the American film’s deficiencies on the presumed technical limitations imposed by the early talkies. But even a cursory viewing of the Spanish film (a stunning, though incomplete archival print at the Library of Congress was struck from the original nitrate negative in 1977) demonstrates without question that there was no dearth of capabilities on the Universal lot, only a misuse of them.

For the title role, Kohner and Melford selected a thirty-eight-year-old stage actor from Cordoba, Carlos Villarias Llano, who worked under the name Carlos Villarias (for some inexplicable reason, probably a mistake, his name on the opening credits of the film itself would be further shortened, to “Carlos Villar”). Villarias would later be seen occasionally in English language roles during the thirties and early forties, including the part of the headwaiter in Bordertown with Paul Muni and Bette Davis in 1935.

For “Juan Harker” the choice was Barry Norton, a multilingual juvenile whose publicity painted him as the truant son of a wealthy Argentine family. Norton, the former Alfredo Biraben, had been directed by F. W Murnau in the circus drama Four Devils for Fox and was also seen in What Price Glory. Dr. Van Helsing was played by Eduardo Arozamena, a popular Mexican character actor whose career would last until the early 1950s. The role of Renfield went to Pablo Alvarez Rubio, a prizewinning actor, journalist, and orator from Spain who began his work in films in 1927. As the raven-haired Lucia, Carmen Guerrero was beginning a film career that would bring her a popularity among Spanish-speaking audiences rivaling Lupita Tovar’s.

The Spanish version of Dracula follows the original shooting script far more carefully than the American film, enhancing its visual suggestions rather than undermining them. The independent mood of the two films is established with the main titles. Instead of the static art deco bat of the Browning version, the Spanish film superimposes its credits over a guttering candle that is quickly extinguished, transporting us from the illuminated world into a realm of darkness.

The film opens with outtake footage of the same glass shot that opens the American film, with a coach rumbling up a desolate mountain pass. Contrary to some accounts, the two versions of the film actually

have no footage in common, though the Spanish film does employ unused negative from the Browning film. The scenes with the Transylvanian peasants are rather flatly played, but by the time Renfield (for some reason, the name is spelled in publicity materials and pronounced in the film as “Rendfield”) is on his way to Castle Dracula, the film comes into its own. We are shown the king vampire rising from his earth-box in a glowing cloud of mist—a flawlessly executed double exposure, and a grand effect. (Instead of dealing with such technical challenges, Browning and Freund simply averted their camera’s gaze at the first hint of a trembling coffin lid.)

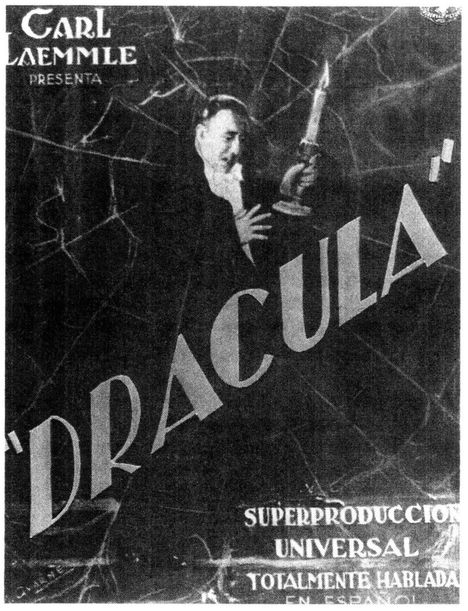

“Totalmente hablada en Espanol”: advertising art for the Spanish Dracula (Author’s collection)

The mysterious driver who meets the traveler at the Borgo Pass is muffled with a black scarf (unlike the American film, in which Lugosi’s face is inexplicably uncovered and completely recognizable as Dracula). The ride to the castle is longer and bumpier than in the American film, and Pablo Alvarez Rubio as Renfield is considerably more frightened than his American counterpart, Dwight Frye. All doors, even coach doors, creak as though they weigh a ton. Renfield finds the great hall of the castle empty—and devoid of armadillos. As he approaches the base of the huge staircase, a bat swoops down at him again and again. He waves it off with his cane, turns—and then, in one of the film’s supreme visual moments, the camera pulls back to reveal Dracula, who has appeared out of nowhere, holding a candle at the top of the stairs and framed by the giant, backlit spiderweb. Without a cut (the camera was mounted on a moving crane13) our field of vision rushes forward up the steps, until the full-length figure of the vampire fills the screen. A familiar exchange of dialogue ensues (adapted in Spanish by B. Fernandez Cue), including the reminder that “la sangre es la vida” and praise for the night-music of “los hijos de la noche.” The scene in Dracula’s chambers is marked by more fluid camera work and enhanced lighting. Robinson’s camera pulls back into an arched alcove for a Nosferatu-like composition. A tall, ornate chair that was featured in both The Cat and the Canary and The Cat Creeps is placed centrally in the room, and the dead branches outside the looming windows are lit in ghostly relief. Robinson also makes dramatic use of firelight and candles as Dracula and Renfield discuss the terms of the Carfax Abbey lease. Instead of a paper clip, Renfield cuts his hand on a knife he is using to demolish a roasted chicken. As he does so, Dracula’s eyes fill the screen in an intense, quivering close-up.

The third reel of the Spanish Dracula has been a matter of some speculation in American film circles for a number of years. The negative had fallen prey to nitrate decomposition by the time the American Film Institute made an archival print for the Universal retrospective at

the Museum of Modern Art in 1977. Sadly, this reel contained some of the most interesting material, including Dracula’s vampire wives, the scene aboard the doomed ship, and the scene at the London concert hall where Dracula first encounters the main characters.

Promotional herald for the Spanish Dracula (Author’s collection)

A complete print, however, had been long rumored to be in the possession of the Cuban Film Archives in Havana. With the generous cooperation of the Cinemateca de Cuba and the permission of the U.S. Treasury Department (whose regulations restrict the travel of United States citizens to Cuba) this author was able to visit Havana in June 1989 to study in detail the only complete print of the Spanish Dracula in existence. It had, coincidentally, just enjoyed a brief public revival at the Cinemateca’s theatre, the Rampas, in downtown Havana. And it was no disappointment.

Following Dracula’s exit (dramatically framed in an arched door—a distinct homage to Nosferatu), Renfield begins to feel the effects of the drugged wine. He pulls at his collar, and the crucifix falls away from his neck (Browning never explained how Dracula was able to attack Renfield when the cross that had just repelled him was still so snugly in place). Renfield staggers toward the window. Robinson then sets his camera outside the window, shooting in as Renfield struggles

with the latch. He doesn’t see the three vampire women who have suddenly materialized, approaching him from behind. He opens the window, only to encounter a flapping bat in the foreground. (This shot is one of the best, and most nightmarish, uses of Robinson’s three-field technique, involving the viewer in a complicated, participatory conspiracy. The audience can see what the focal character cannot, its attention being pulled in three directions simultaneously.)

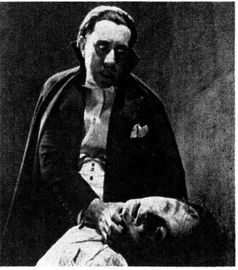

Carlos Villarias re-creates Bela Lugosi’s classic pose on the castle staircase. (Author’s collection)

Unlike the actresses in the American film (zombie schoolmarms with tight braids and robotic demeanor) the Spanish vampiras are

wild, exotic creatures with flowing hair and low-cut gowns. As they slither forth, there is one dramatic close-up of their faces—one with teeth bared, and another, the center of the image, backlit in such a way that her nimbus of blonde hair frames not a face but a shadow. It is, without question, one of the great, if hitherto unheralded, images from the horror films of the 1930s, and a marvelous evocation of Stoker’s original vision: “Two were dark, and had high aquiline noses, like the Count’s, and great dark, piercing eyes … . The other was fair, as fair as can be, with great wavy masses of hair and eyes like pale sapphires. I seemed to know her face, and to know it in connection with some dreamy fear, but I could not recollect at the moment how or where: All three had brilliant white teeth, that shone like pearls against the ruby of their voluptuous lips.”

Renfield looks into the courtyard and sees the Count watching an earth-box as it is lowered onto a wagon. The scene is shot from a low angle, through a stylized clutch of dead branches echoing the art direction of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Renfield falls in a faint and the vampire women swirl around him, swooping for his throat as the scene fades out.

In contrast to the American film, the Spanish Dracula establishes the ship scene en route to England without the formality of a title card, and without dialogue. Both films intercut separate storm-at-sea clips from the same silent maritime drama. Although this sequence is composed of almost the identical number of shots in both versions, the Spanish is by far the more chilling and evocative, and is quite obviously influenced by the analogous scene in Nosferatu. Neither version achieves quite the effect of the screenplay’s ambitious concept (sailors being stalked, one by one, and leaping into the sea; a triumphant Dracula on the bow of the ship, his cape open to the storm like a billowing black sail) but the Spanish film provides the superior treatment. While we don’t see the sailors’ watery death-leaps, we do see their terrified faces in close-up. A snarling Dracula emerges from the ship’s hold in another Nosferatu-inspired image, while Renfield’s face is glimpsed in a porthole, laughing maniacally. Real rats add to the occasion, crawling on Dracula’s coffin lid and swarming around Renfield when he is discovered in the ship’s hold. When the hatch is opened, he screams as if scalded by the sunlight.

Ensconced at Carfax Abbey, Dracula once more emerges from his

earth-box in a halo of glowing mist. A brief outtake of Bela Lugosi in the American film is intercut, showing Dracula’s arrival at the London concert hall. Robinson makes a striking triangular composition of actors, curtains, and an overhead light fixture as the vampire peers into the box where the principal characters are seated. His fateful lines to Lucy (Lucia here), “There are far … worse things … awaiting man … than … death,” are delivered as the houselights dim, leaving Dracula almost completely in shadow and Lucia’s face isolated in darkness by a tight, oval spot. The third reel ends with an outtake from The Phantom of the Opera (1925), showing the curtain rising on a corps de ballet.

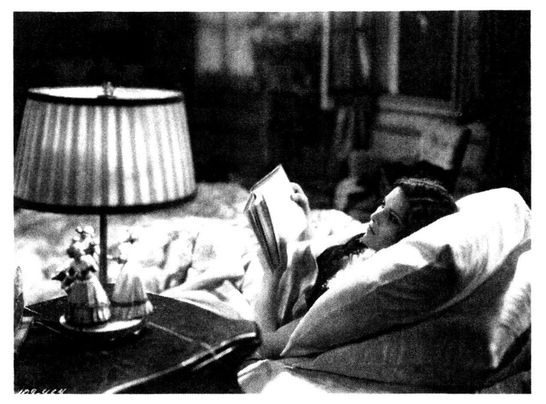

The film does suffer from the same stage-bound sluggishness as the American film, but Melford, Robinson, and Kohner are consistently resourceful in enhancing the mood and action. The women’s costumes are startlingly sheer and revealing for a film of the period (To-var recalled, “My negligee was very low-cut. When my grandson saw the film, he said, ‘Now I know why Grandpapa married you!”’). The sexual aspects of the story are accentuated rather than minimized: when Dracula attacks Lucy in her bedroom, he covers her with his cape like a huge crawling bat, an image both ugly and erotic. The American film settles for a discreet fade-out. Tovar’s Eva—once more, the heroine has undergone a change of name—becomes sexually animated as the vampire’s spell overtakes her. Helen Chandler, by contrast, seems merely dazed. There is a rather more generous use of fog and mist, and shots are framed to take full advantage of the high, detailed interiors. Issues left dangling in the American film are resolved: Renfield’s attack on the fainting maid is merely a bit of comic relief (he’s only after a fly that has alighted on her), and the vampire Lucy is tracked to her crypt and properly dispatched (Browning leaves her wandering in the night, as if looking for a sequel). A glass shot of Carfax by the rolling sea is seen twice in the film; the huge upstairs staircase that Browning wasted is used, though briefly.

Charles D. Hall’s impressive Castle Dracula set was re-dressed and relit for the Spanish production. (Author’s collection)

The death of Renfield is handled particularly well. Browning stages a rather inept stunt with Renfield’s body flopping down a flight of stone steps, the “stone” thumping hollowly as he does; in the Spanish film, Dracula hurls his unfortunate slave over the side of the steps in a completely unexpected and violent coup de théâtre.

The Spanish Dracula began shooting the night of October 10, 1930. “The American crew left at six and we were ready,” Tovar recollected. “We started shooting at eight. At midnight, they would call for dinner.” Kohner had wisely seen that he could save a great deal of time by shooting out of sequence, and scheduled scenes and sets accordingly. Tovar recalled that a Movieola was kept on the set, on which footage shot for the American film could be viewed by the creative team. The actors, with the single exception of Carlos Villarias, were not permitted to view the English-language dailies. Villarias was encouraged to be as Lugosi-like as possible. The actor even wore Lugosi’s hairpiece, and in several scenes the resemblance is uncanny. There were differences, however. Villarias was notably lacking one of Lugosi’s most distinctive physical characteristics: the long, expressive Henry Irving–like hands. Villarias had small hands and short fingers, more like paws than talons.

The casts of both films were introduced. The Americans, Tovar remembered, “were very nice, but condescending. We were the children

and they were the grown-ups, you see.” And unlike The Cat Creeps, Kohner was not welcome as an artistic consultant to Browning. The obvious joint photo opportunities never happened, and the productions proceeded on their separate tracks and levels. The Spanish film was moving so quickly that many of the sets were not completely finished when Kohner was ready for them—Carfax Abbey, for instance, was completely devoid of cobwebs and dust. Nonetheless, Kohner’s crew barreled ahead, and compensated with atmospheric lighting. The cast and crew were remarkably free of temperament. “They didn’t pay us much, but we didn’t complain,” said Tovar. “We were happy to have some money—most actors were starving. So it was manna from heaven. We had tremendous respect for George Melford—the director of Valentino was, to us, like a god. We did everything that was required of us, worked twenty-four hours a day, did publicity. We were the most obedient crew. And there was no union then.”

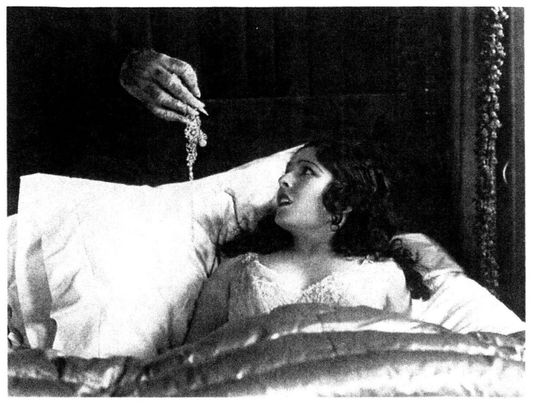

Unaware that Dracula stands below her bedroom window, Lucia (Carmen Guerrero) prepares for her ultimate sleep. The composition of the shot is typical of cameraman George Robinson’s consistent use of foreground elements to convey depth and visual interest. The same lamp, incidentally, appears next to the heroine’s bed in Karl Freund’s The Mummy (1933)—one of several set pieces borrowed from Dracula, along with the title music and most of the plot. (Author’s collection)

Kohner’s courtly attentions continued through the production, prompting Tovar’s costar Barry Norton to kid her about her weight. “If you keep eating Paul Kohner’s candies, Dracula won’t be able to carry you up those stairs,” he told her. “The head electrician was a Mexican named Tommy Valdez,” Tovar remembered. “He used to watch me from the catwalks. Every once in a while when I was sitting between takes, a Hershey bar would drop down.” The crew took to signaling Tovar from above when there was something in her performance they liked.

The Spanish Dracula finally wrapped on November 8, after only twenty-two nights of shooting (compared to seven weeks for the American version) at a final cost of $66,069.35, almost twenty-seven hundred dollars under budget.

Kohner scheduled a preview on the Universal lot for the first week in January 1931, more than a month ahead of the American Dracula’ s release. Retakes were still being shot by Browning as late as January. The January 10 issue of Hollywood Filmograph opined that “If the English version of Dracula, directed by Tod Browning, is as good as the Spanish version, why the Big U haven’t a thing in the world to worry about.” (It would, of course, eventually worry about the Filmograph’ s less-than-warmhearted review of Browning’s effort.)

Paul Kohner (left) and director George Melford (center) give Carlos Villarias tips on the best angle of approach to Carmen Guerrero’s essential erogenous zone. (Author’s collection)

“The other evening before a capacity theatre on the lot there was a screened preview of the Spanish version which was witnessed by Bela Lugosi … and to use his own words the Spanish picture was ‘beautiful, great, splendid.’” The Filmograph complimented all concerned, but saved its best praise for Paul Kohner. The Spanish Dracula was “far above anything he has yet turned out on the lot. Kohner knows the foreign picture desires perfectly.”

Dracula opened to good business in Mexico City on April 4, where it played throughout the month of April. In contrast to the American pattern of release, it opened first at the Cine Mundial, a cine de barrio or neighborhood theatre, building word of mouth for a four-theatre engagement in the primero circuito of the Monumental, Teresa, Odeon, and Granat cinemas. The Mexican papers were full of praise for Tovar (“La Novia de Mexico”) and Villarias. A headline in the Mexico City daily El Universal promised that “Dracula Will Amaze Mexico,” with the article declaring the film to be a “positive triumph.” Another evaluation found Dracula to be “disturbing,” but admitted it was “unlike anything we’ve seen before on the screen.” The film migrated north to Los Angeles, and opened with some fanfare in the Spanish press (considerably more than had greeted the American film) on May 8 at the California Theatre. Bela Lugosi made a guest appearance on stage with Tovar and Villarias as part of the festivities. For one week, it was possible to see both the English and Spanish versions of Dracula at theatres only a few blocks apart—the Spanish version at the California and the American at the Fox Palace. The Spanish Dracula was also well-received in its New York City engagements at Manhattan’s San Jose Teatro Hispano and Brooklyn’s Teatro Gil for several weeks in April and May.

Lupita Tovar remained in Hollywood, and became Mrs. Paul Kohner the following year. The couple was married in Europe, where Paul was trying to handle Universal’s affairs just as Hitler’s shadow had begun to ominously lengthen. “Hitler will be over in three months,” Kohner told her. “Good,” Lupita replied, “we’ll come back in three months.”

Back in the States, Kohner found himself without a job when Carl

Laemmle, Sr., sold the studio in 1935; he had worked for Universal without a formal contract. Unable to secure a steady post at another studio, he turned to freelance agenting, and eventually established himself as one of the most respected international talent agents in the business. His fifty-year friendship with the late John Huston would also become the longest client-agent relationship in Hollywood history. The Kohner’s children and grandchildren carried on the family’s cinematic legacy. Susan Kohner received an Academy Award nomination as the black daughter passing as white in 1959’s Imitation of Life, and played Montgomery Clift’s wife in John Huston’s Freud (1962). Her brother, Pancho Kohner, became a respected producer, best known for Charles Bronson blockbusters. Susan Kohner married fashion designer John Weitz, and their sons, Paul and Chris Weitz, firmly established themselves as Hollywood players at the helm of American Pie (1999).

A still from the Spanish film and a scene from Nosferatu show a striking similarity of set designs. Nosferatu was studied carefully by Universal’s artistic and technical crew. (Author’s collection)

Paul Kohner never retired, and, ironically, just before his death in 1988, he agreed to be interviewed by American Cinematographer magazine on the making of the Spanish Dracula. It was just another of the countless fascinating tales that could be told only by a cultured and gregarious man whose professional life had virtually encompassed the history of motion pictures.

Sadly, the interview never took place. Paul Kohner died March 16, 1988. No doubt he had many other stories to tell besides the one reconstructed here without his recollections, but simply not the time to tell them.

The Spanish Dracula would be one of the last foreign-language films produced in Hollywood. The Depression had taken firm hold, and most of the large studios were hemorrhaging money and cutting back even on their domestic productions. Talking pictures were beginning to be produced at home by the countries that had previously looked to Hollywood for entertainment. The age of doppelganger cinema was at a close. The Spanish Dracula was shown theatrically in Spanish-speaking countries until the 1950s (the complete version in Havana is a 1950s show print). For obscure reasons, Universal never registered the copyright on the film, nor did it make preservation prints on safety stock. With the demise of foreign-language talkies, the film was considered to have no commercial future and was simply forgotten. The incomplete negative was rediscovered in Universal’s New Jersey storage facility in the late 1970s, and archival copies were struck as a preservation project of the Library of Congress. The film was screened for the public only a handful of times, most notably at the Museum of Modern Art and the Telluride Film Festival, but without the missing third reel had no real prospects for restoration.

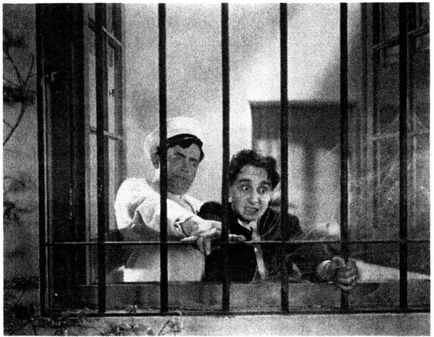

Renfield (Pablo Alvarez Rubio) is restrained by the asylum attendant (Manuel Arbo). Rubio has much more screen time than his American counterpart, Dwight Frye, and gives an independent performance. Of the cast, only Carlos Villarias as Dracula was permitted to watch the American rushes and study the Lugosi performance. (Author’s collection)

The death of Renfield was more violent in the Spanish film. (Courtesy of David Del Valle / The Del Valle Archive)

Following the publicity generated by the original edition of Hollywood Gothic, Universal embarked on a meticulous restoration of the Spanish Dracula with the assistance of the UCLA Film Archive, which obtained the missing reel from Havana. Because of U.S. Treasury restrictions on commercial trade with Cuba, Universal could not directly do business with the Cuban archive. Educational institutions, on the other hand, had considerably more latitude. The restored print was unreeled at the Director’s Guild Theatre in Los Angeles in November 1992, the same day as the premiere of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

In the late 1990s, filmmaker Gregory Nava, director of the pop star biopic Selena (1997) with Jennifer Lopez, proposed a romantic comedy based on the story of Lupita Tovar, Paul Kohner, and the production of the Spanish Dracula. Despite the intriguing possibilities of the concept, Nava was unable to reach an agreement with the Kohner family, and the project was ultimately abandoned. But the Spanish Dracula itself went on to an active afterlife on video and DVD, an object lesson in the importance of historic film preservation, and proof that, while Dracula as a film might be filled with cobwebs, it should never have been condemned to collect them.