Gloria Holden as Dracula’s Daughter (1936), the first of many aspirants to the vampire throne (Author’s collection)

THE DRACULA CENTURY

In which fortunes rise and fall, and pretenders to the throne proliferate,

and in which the picture people will not leave an actor to his grave,

and battle for the possession of his immortal soul.

and in which the picture people will not leave an actor to his grave,

and battle for the possession of his immortal soul.

“HIS PECULIARITIES CAUSED HIM TO BE INVITED INTO EVERY HOUSE,” wrote John Polidori of his Dracula prototype Lord Ruthven, and the same could be said of Dracula himself. In the twentieth century, there would be no corner of the world impervious to his invasion, with or without a formal invitation.

The vampire’s first champion, Florence Stoker, may not have been a happy woman, but she had triumphed in one regard. She had wrestled with Count Dracula, the dark spectre of her husband’s problematic unconscious, trained him, domesticated him, sent him out into the world to make money, and she had succeeded. The monster was her main asset, and she protected it furiously. And in the end the demon became her own protective familiar, her guardian angel and salvation. “She was very hard up,” confirmed Stoker biographer Daniel Farson. “The Universal film saved her.” The money from Universal enabled her to make renovations in her mews house in Knightsbridge, amid the zigzagging alleys, in the shadow of grander homes.

Vincent Price, before his career as an actor, was an art student at London’s Courtauld Institute, and one day in 1935 had the chance to meet the woman who had known nearly all, and inspired several, of the major Victorian artistic and theatrical personalities. “Mrs. Stoker invited me to tea in her small, fabulous mews house,” Price told this author. “Among her treasures were portraits by Wilde, Burne-Jones and Rossetti. All her books were signed by the great literati of her lifetime. She was very petite and almost blind, very dear and still very beautiful. I felt I’d stepped into a most romantic past.”

In 1933 Florence Stoker had sold an option on the film rights to the short story “Dracula’s Guest” to David O. Selznick, who was then running his own unit at Metro Goldwyn Mayer. Selznick intended to produce from it a film called Dracula’s Daughter, and his right to use that specific title was part of the option. Stoker was paid five hundred dollars against a five-thousand-dollar purchase price. Selznick hired John L. Balderston to write a treatment, but was unable to persuade MGM to produce it. It wasn’t just that Balderston’s initial concept, depicting Dracula’s daughter as an outrageous dominatrix, complete with whips, chains, and rapturously masochistic male lovers, would cause problems with the censors (the Production Code was then approaching full force). The studio was instead extremely concerned about infringing on Universal’s ownership of the original novel, its title and theme, and regarded its deliberations as so sensitive that they adopted the code name Tarantula for their discussions of the property by cable and letter.

The first Modern Library edition appeared in 1932. (Author’s collection)

Selznick ultimately sold his option to Universal, who at first assigned director James Whale and his screenwriter R. C. Sherriff to make a sardonic black comedy of Dracula’s Daughter, in the manner of Whale’s 1935 sensation The Bride of Frankenstein. Though killed at the end of the 1931 film, Bela Lugosi would return in a historical prologue depicting his original transformation into a vampire. Sherriff must have listened to Lugosi’s screen work carefully, and wrote pages of plummy dialogue beautifully tailored to Lugosi’s unique delivery style. Another role, conceived for Boris Karloff, was that of a Transylvanian wizard, who rises up against Dracula on behalf of the virgin-pillaged countryfolk, gate-crashes one of Dracula’s bacchanals, and transforms the Count’s debauched guests into pigs, monkeys, and snakes, while condemning Dracula alone to eternal life as a vampire. Sherriff imagined a visual tour de force for the end of the sequence, which remains one of the great unrealized moments from Hollywood’s golden age of horror films. Within a matter of seconds, Dracula’s banquet table, the corpses of his animalized guests, and the tapestries and furnishings of his great hall would all crumble into dust and ruin, representing the passage of five centuries.

Sherriff, however, had loaded his script with the kind of sadistic violence clearly not permitted by the Production Code. The most grotesque was a scene in which Dracula, his face hidden by Arabian robes, tricks one of his nubile abductees into believing he is her husband, come to rescue her. The hand and ring she sees are indeed his. But when she approaches, Dracula throws off his raiment, revealing her beloved’s severed arm.

In all likelihood, it was Whale who encouraged Sherriff to go over the top—he had fought his own major battles over The Bride of Frankenstein, and may have decided to give the censors some distracting raw meat to chew on, the better to maintain control over a film he

really wanted to make in a more subdued key. It was not an unknown tactic, and is still used today. But Production Code officials clamped down especially hard on Dracula’s Daughter and branded Sherriff’s work as unproducible, revision after revision after revision. Among other things, Dracula himself was now considered an insult to public morality, and Lugosi was denied a job. Whale and Sherriff moved on to other projects, and producer Carl Laemmle, Jr., after producing Whale’s extraordinary (and arguably definitive) Showboat (1936) moved on, period, his father having lost financial control of the studio and being forced to sell. Dracula’s Daughter was produced under new Universal management, with a new script by Dracula veteran Garrett Fort, greatly amplifying the homoeroticism he only intimated in the 1931 scenes between Dracula and Renfield. In Dracula’s Daughter, Countess Maria Zaleska (Gloria Holden) was portrayed as a rich, yet “bohemian” artist attracted to both psychoanalysis and nude female models. Directed by Lambert Hillyer, Dracula’s Daughter eliminated the nudity, but the scene in which Zaleska victimizes a streetwalker in her studio remains one of Hollywood’s more memorable coded allusions to lesbianism.

The complicated contract questions raised by Dracula’s Daughter brought new scrutiny to the copyright status of Stoker’s book, and research turned up an astonishing fact: Dracula was—and always had been—in the public domain in the United States. Although Stoker had applied for a copyright certificate in 1899, and his widow had warranted to Universal that she had received a renewal certificate dated April 1, 1924, Stoker had failed to comply with the requirement that two copies of the work be deposited with the American copyright office “on or before the day of publication in this or any foreign country.” The “renewal” had been a copyright office bungle. In fact, Universal had considered doing Dracula as a silent film as early as 1915, but concluded then that the copyright was “clouded.”

All of the Dracula negotiations, then, the effort to suppress Nosferatu in America, even Horace Liveright’s contract for the stage play, had been based on an extraordinary shared delusion. Within the borders of the United States, anyone had been entitled to produce whatever kind of adaptation of Dracula they chose, without considering Florence Stoker at all.

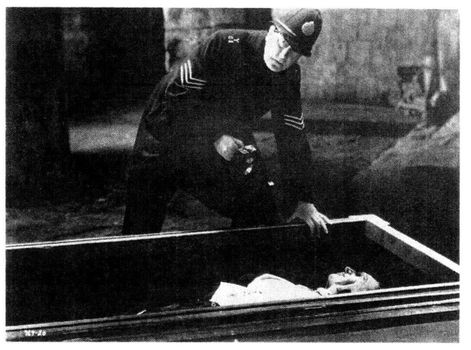

Once the censors were finished with Dracula’s Daughter (1936), all that remained of Bela Lugosi’s proposed role was a wax dummy in a coffin. (Author’s collection)

But she had won in spite of everything, transforming Dracula into a personal allegory of female transformation and empowerment.

The widow’s health deteriorated. Her last act having anything to do with Dracula was the authorization of a British magazine serial called Dracula’s Daughter, which had nothing to do with the Universal film. The end came in May 1937, from colon cancer. Her will, published two months later, revealed that she had left £6,913, with net personalty valued at £5,921. She made three specific bequests. To the Victoria and Albert Museum, “All her Nailsea glass, including a window stop in the form of an animal and a blue Bristol glass roller, and also her Sheffield toastrack in the form of a lyre.” To the London Library was left her collection of Maria Edgeworth books, and to the London Museum a statuette of Henry Irving in aluminum and his hand in bronze, both by Onslow Ford, as well as a pastel portrait of Irving by Sir Bernard Partridge (which Bram Stoker had been forced to buy from the Irving estate, Stoker himself having been forgotten in Irving’s will).

F. W Murnau, who had invented the vampire movie with Nosferatu , was working in Hollywood at the time Dracula was filmed, and gave numerous interviews on his many films, but never commented publicly on Nosferatu and its debacle. His opinion of the authorized Dracula would never be known; he was killed in an auto accident near Santa Barbara shortly before the film’s West Coast release.

Director Tod Browning returned to MGM after Dracula, but never recovered the standing he had achieved through his professional link to Lon Chaney. His most celebrated film, Freaks, proved an embarrassment to Metro, which withdrew the picture from circulation. An anomaly itself, Freaks was exhibited by independent exploitation outfits under such titles as The Monster Show and Nature’s Mistakes. In Great Britain, it was banned outright for thirty years. It enjoyed a theatrical revival in the ’60s and ’70s, a cult following in France, and was shown on American television for the first time in 1990. Browning is said to have wanted to direct a film adaptation of Horace McCoy’s scathing Depression-era novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? but, lacking political leverage, was unable to interest Metro. Browning made his last film in 1939, and retired comfortably on his real estate investments. Until his death in 1962, he is not known to have given a single substantive interview on his career. The critical mystique surrounding Browning’s work is probably fueled by the overwhelming sense of enigma surrounding the man and the private obsessions that drove him.

Karl Freund, the legendary cinematographer, similarly left no accounts of his work on Dracula, and in his later years contented himself with supervising photography for television’s I Love Lucy and pursuing technical research. Freund died in Hollywood in 1969.

Horace Liveright, who understood the enormous money-making potential in both Dracula and Frankenstein, was cut out of the Hollywood largesse from both properties, the victim of his own demons. His stay in Hollywood had been an unhappy one. At Paramount Publix he had been unable to negotiate the film rights for even a single property, least of all Dracula. Returning to New York, with fruitless schemes for books and Broadway plays that would recapture his former celebrity, he found himself in much the same position as Florence Stoker after the passing of the Lyceum’s golden age. Bennett Cerf, one of his few loyal former employees, wrote after his death, “A

poseur to the last, he could be found tapping his long cigarette holder nervously at a table at the Algonquin, a mere shadow of his former jaunty self, announcing ambitious theatrical projects to all the critics … although everybody knew he was playing through a heartbreaking farce.” Penniless and alone, he died of pneumonia on September 24, 1933.

Dracula has attracted a number of self-destructive personalities in its career, and has had a destructive effect on the careers of others. Actress Helen Chandler is a case in point. Highly successful as a New York stage performer—from her extravagant press clippings, it would certainly be safe to call her a toast of Broadway in the late 1920s—Chandler today is remembered for not much else than her appearance in Universal’s Dracula. As with Liveright, her onetime employer, Chandler’s personal vampire was alcohol, compounded by an affinity for sleeping pills. The shadow of chemical dependency was offset by her wistful, childlike manner; even as a young adult, she told interviewers she dreamed of producing and starring in a film version of Alice in Wonderland. By the mid-1930s she was unemployable in films, and returned to the stage, where she often costarred with her second husband, Bramwell Fletcher, the actor who had gone so memorably mad in The Mummy. In 1940 she was committed to a sanitarium. In 1950, she was severely burned on the face, arms, and upper body, the result of drinking and smoking in bed. Her third husband, a merchant seaman, had shipped out a few days earlier.

Chandler’s father gave the Associated Press a peculiar account of her years in obscurity: Chandler, he said, had been stricken years before by a mysterious fever malady, and had impoverished herself by traveling the world over in search of a cure. She died in 1965, following surgery. Her paid death notice in the Los Angeles Times—there was no editorial obituary—listed only a brother as a survivor. Her ashes have never been claimed.

Like Chandler, Dwight Frye had been an enormously popular stage actor in New York before coming to Hollywood and making Dracula. Unlike Chandler, it would not be personal problems but his association with the role of Renfield that would cruelly limit his career. Once prized for his range and versatility, Frye was typecast as the prototypical monster’s assistant. Wild-eyed, hunchbacked, or zoophagous, Dwight Frye became a subgenre unto himself. (He is the

only other performer in the Universal film, besides Bela Lugosi, who would later repeat his role on stage—in Frye’s case, a 1941 production in Los Angeles opposite actor Frederick Pymm.) During World War II, Frye supplemented his income by working as a machinist. His first chance at a major mainstream role was tragically cut short—on November 7, 1944, shortly after being cast as the Secretary of War in the biographical drama Wilson, Frye was stricken with a heart attack on a hot Los Angeles bus as he was returning from a movie matinee with his young son, Dwight, Jr. He died a few hours later. A devout Christian Scientist, Frye had concealed earlier mild coronaries from his family and had never sought medical treatment. The actor’s death certificate, in a final irony, listed his occupation as “tool designer.” Nearly sixty years after the release of Dracula, Frye’s son reported that the name was still frequently recognized when he used his credit cards, and that waiters and shop clerks could be quite willing to give him an impromptu impression of his father’s famous, maniacal laugh from the Universal film.

Among the writers, Garrett Fort’s career took a turn into mysticism, depression, and suicide following his work on several Universal horror classics. His death by sleeping pills was reported in Variety on Halloween, 1945.

Other Dracula alumni fared much better. Actor David Manners appeared in a series of horror and mystery films including The Mummy (1932), Edgar G. Ulmer’s stylized masterpiece The Black Cat (1934), and in the title role of The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1935). Manners intensely disliked Hollywood, although it paid him very well. As a gay man under studio contract, his public life was under constant surveillance, though his private behavior found its own level. “It was a good thing we didn’t have AIDS in those days,” he said in 1991, “because I would have been among the first to get it. I hopped from bed to bed.” After a particularly nasty clash with an obscenity-spouting Joan Crawford (he had turned down the chance to be her leading man), he angrily sped off the Metro lot and didn’t stop driving until he had reached the mountains overlooking the desert. He decided then and there to pursue a private life away from Hollywood. Manners moved to the desert and ran a guest ranch, his discreet clientele sometimes including publicity-averse guests like Greta Garbo and Albert Einstein. He returned to Broadway in the late 1940s for an all-gay

production (a fact not publicized) of Lady Windermere’s Fan, and never acted again. He published two well-reviewed novels in the 1940s, and eventually dedicated his energies to esoteric philosophy and reflection. He occasionally published collections of his thoughts on life’s deeper meanings and mysteries, the last of which was Awakening from the Dream of Me in 1987. He died in Santa Barbara in 1999, five months short of his one hundredth birthday. He always claimed never to have seen Dracula.

John L. Balderston continued to supplement his journalistic and political activities with screenwriting. He collaborated with John Hurlbut on the script of Universal’s most extravagant horror exercise, Bride of Frankenstein, in 1935. In the early 1950s, in poor health and financial need, he sued Universal, claiming that the conception of Frankenstein’s monster he had originated (based on the play by Peggy Webling produced in England by Hamilton Deane) had been unfairly exploited in subsequent Universal films. Balderston and Webling (who died in 1947) had sold Frankenstein to Universal in 1931 for twenty thousand dollars plus 1 percent of gross earnings. Their earnings were considerably compounded when the case was settled in May 1953; Universal reportedly paid Balderston and the Webling estate more than one hundred thousand dollars in exchange for all rights to the character. Balderston maintained his good humor about Dracula, and in 1944 shared a brainstorm with his agent, Harold Freedman: “Sell Dracula as a musical! Get that DeMille girl to do a ballet of the vampires in the middle of the tombs and go to town on the thing as the first ‘horror musical.’ It should of course be played and sung straight,” Balderston wrote, adding that “the audience would howl and tear up the chairs and everybody concerned would make a great deal of money.” Freedman doesn’t seemed to have taken him seriously at the time, but eventually the outlandish-sounding idea came to pass: Dracula has been reproduced more than once as both musical and ballet. Balderston, however, never saw them; he died in Beverly Hills in 1954.

Disenchanted with Hollywood, actor David Manners claimed to have never seen his most famous film. (Author’s collection)

Following the death of Florence Stoker, Hamilton Deane was finally able to enter into a standard and equitable stage contract with the widow’s son, Noel, for the Balderston adaptation (which Stoker had never permitted Deane to play in England). He brought his own version back to London in 1936, and in 1939 Deane finally essayed the title role himself in a West End production of the Balderston adaptation, directed by (and costarring) Bernard Jukes. Jukes (who was to Renfield what Yul Brynner was to the King of Siam, having played the role almost nonstop from 1926 through 1929, though not the four thousand performances claimed in his publicity) died on December 31, 1939, at the age of forty-one. Deane continued to play Dracula in stock until 1941, before hanging up the cloak forever. He could never have imagined the degree to which Dracula, which had begun as just another play in his traveling repertory, would succeed in dominating his professional life. He died in 1958.

Carl Laemmle, Jr., remained at Universal’s helm over several financially rocky years until the sale of the studio in 1936. Though often criticized for his inexperience and impetuousness, Junior Laemmle managed to keep Universal’s losses well below those of other major studios during the Depression. In establishing the American horror film as a distinct genre, Laemmle almost single-handedly inspired one of the most consistently profitable categories in film history. His at-tempts

to set himself up as an independent producer failed, and he withdrew from the Hollywood scene. A legendary hypochondriac, who avoided physical contact and feared he might die if he slept in a bed other than his own, Laemmle did, ironically, meet up with serious illness. Crippled by multiple sclerosis in the early 1960s, he lived in seclusion as a wealthy invalid until his death. In an eerie coincidence that underscored the lifelong influence of the father to whom he had relinquished his name, Carl Laemmle, Jr., died of a stroke on September 24, 1979←precisely forty years to the day after the death of Carl Laemmle, Sr.

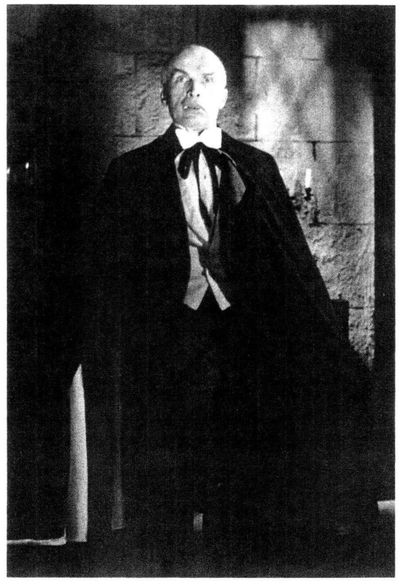

The only known photograph of stage impresario Hamilton Deane in the role of Dracula (Courtesy of Frank Dello Stritto)

But the saddest, most dramatic casualty of all those who crossed the path of Dracula is without question Bela Lugosi, whose overwhelming identification with the role blurs meaningful distinctions between illusion and reality, vampire and victim, even between life and death. Lugosi’s tragedy is second, perhaps, only to that of Marilyn Monroe as a story of the complete entrapment of a performer by an archetypal screen persona. (Indeed, curators of research collections

across the country reported to the author that Bela Lugosi memorabilia ran a close second only to Monroe’s in its probability of being stolen. These twin icons of sex and death have the equal ability, it seems, to incite monomaniacal possessiveness and desire. In Dracula worship, there is death-in-sex; in postmortem Monroe worship there is sex-in-death. In Monroe’s case, there is more than metaphor. Her crypt, in a memorial park coincidentally adjacent to the author’s hotel in Westwood during a research trip for this book, was observed to be smeared with lipstick bearing the fresh imprint of a human mouth. The vault’s marble slab had settled, or been forced, sufficiently to allow, if the visitor desired, the insertion of a finger into the cavity.)

Dracula marked both the beginning and the end of Lugosi’s Hollywood career. Carl Laemmle, Jr., had wanted to groom him as “the new Lon Chaney,” and some advertisements for the 1931 film actually included the tagline. But Lugosi’s fortunes at Universal began to dwindle after he refused to play the monster in Frankenstein. Test footage was shot on the Dracula set, with Lugosi unrecognizably padded and made up. He objected to the makeup, and to dialogue which consisted of nothing but grunts. Lugosi’s objections to the part were quite legitimate—as written, it was indeed the “scarecrow” he famously complained about—but instead of rewriting the part for him, Universal ejected both Lugosi and his planned director, Robert Florey, and input Boris Karloff, a relative unknown, who shot to stardom with the role. He was a more versatile actor than Lugosi, who had stepped directly into the trap Conrad Veidt had fled Hollywood to escape. Karloff could affect a range of accents, for instance, while Lugosi had only one: the Dracula voice. Karloff sat still for heavy makeup; Lugosi didn’t want his features hidden. And yet he fumed and raged at Karloff’s ascending star (according to one account, in the middle of the night a few days before his death, Lugosi’s wife would find him awake and confused, convinced that Boris Karloff was outside, waiting for him). With the Dracula contract, Lugosi had proved he could be had cheaply. One of his next films, White Zombie, was an independent quickie shot on the Universal lot, making use of some re-dressed Dracula sets and properties. The atmospheric film, now regarded as a classic, re-created his Dracula contract on a

poverty-row level as well. His total payment for a week’s work on the film, which made a million dollars for the Halperin Brothers, was reputed to be between seven hundred and nine hundred dollars, and was possibly even less.

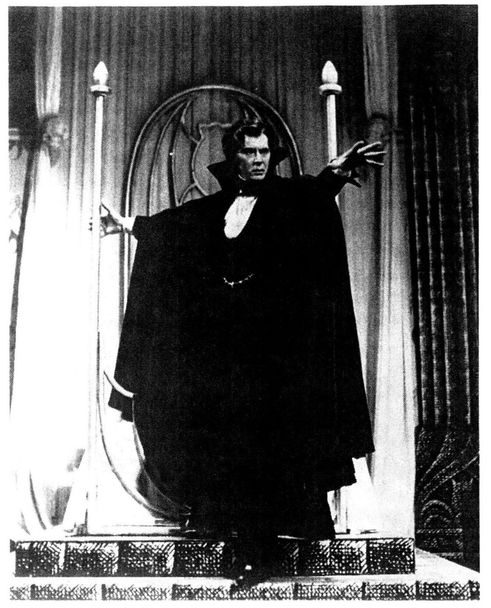

Prestige roles eluded Lugosi. He was rumored to be a contender for Rasputin in Rasputin and the Empress, but the part went to Lionel Barrymore in a casting coup that brought all three Barrymore siblings together (John and Ethel played the royals). Max Reinhardt grandly announced that he intended to make a film of Faust starring Fredric March, Greta Garbo, and Bela Lugosi as Mephistopheles. It never happened. Lugosi’s appearance in Tod Browning’s Mark of the Vampire for Metro could hardly have endeared him to Universal, which (it is rumored) tried unsuccessfully to block the picture as an infringement of Dracula.

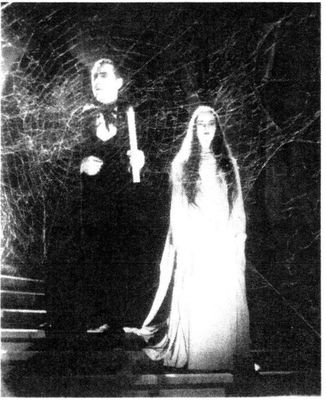

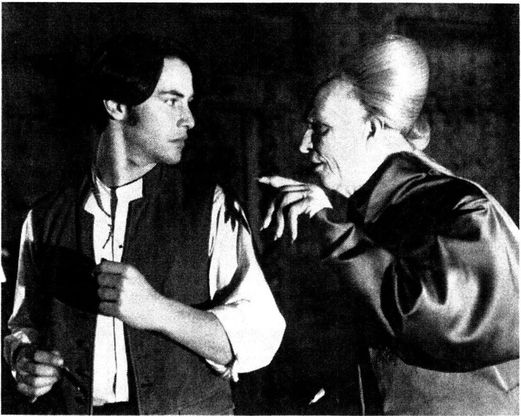

Bela Lugosi and Carroll Borland in Tod Browning’s Mark of the Vampire (1935), a film which drew equally upon Browning’s Dracula (1931) and London after Midnight (1927) (Author’s collection)

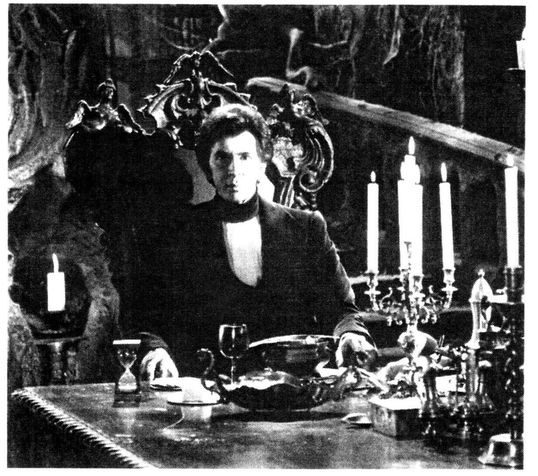

Lugosi was an undeniably talented performer, who shone especially in ethnic or lowlife characterizations. His work as the demented Ygor in Son of Frankenstein is a splendid example of the actor at the height of his powers. After the mid-1930s, Lugosi struck less and less of a figure in evening wear, but fish-and-soup was part of the old Dracula formula and the look was insisted upon in film after film. Universal overlooked him for three Dracula films in the 1940s: Son of Dracula (1943) put Lon Chaney, Jr., in the role, and John Carradine donned the cape for House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945). The latter presents vampirism as an addiction the Count unsuccessfully tries to shake; had Lugosi played the role, it would have been underscored by the irony of his own growing dependency on prescription painkillers. During this period, Columbia Pictures hired him for Return of the Vampire (1943), in which he played Dracula in everything but name; for copyright purposes, the vampire’s name was Armand Tesla. Although it may have seemed to the filmgoing public that Lugosi played nothing but Dracula, in reality he officially portrayed the part only twice on the screen, first in 1931 and finally in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein in 1948.

Frustrated by studio typecasting, Lugosi looked vainly for a stage role that might undo the Dracula curse, but producers resisted offering him anything but the Deane and Balderston script, often on insulting terms. He was once given the chance to play the part in Bermuda, for example, but only if he would pay for his own transportation. Lugosi changed agents frequently, frustrating them with his periodic refusals to accept any engagements in Dracula at any price. But soon reality would set in and the agents would be sending out their feeler letters. Yes, they would write almost penitently, Mr. Lugosi is available again for Dracula, and yes, on almost any terms … .

Veteran Broadway actress Elaine Stritch played opposite Lugosi in a 1947 stock production of Dracula at the John Drew Theatre in East Hampton. (In addition to Stritch’s Lucy, the cast included Ray Walston as Renfield.) In a 1990 interview with this author, Stritch recalled Lugosi as an actor who took his work seriously, to the point of wearing full costume from the first day of rehearsals. After work, Stritch related, “he’d take us out to knock back a Scotch, and told some wonderful stories. He was a very good actor, you know, but he wasn’t lucky professionally. I remember him telling me, ‘You know,

Elaine, if it wasn’t for Boris Karloff I could have had a corner on the horror market.’” It was no doubt a further irritant to Lugosi that the only other stage part he could successfully tour was the Karloff role in Arsenic and Old Lace.

Poster for Son of Dracula (1943) (Photofest)

Stritch’s most vivid memory of the Dracula revival was its opening night. The actor who played Jonathan Harker was having more than a bit of trouble with his climactic line in the crypt: “Let me drive it in deep!” had given him the giggles all through rehearsals and had caused some concern among the company. By the end of the first performance, however, he managed to deliver the line perfectly. He placed the wooden stake over the Dracula dummy’s heart while Lugosi crouched behind a curtain, prepared to give a frightening cry. He raised the hammer, swung it down … and missed. The rubber hammer bounced off the dummy, Lugosi gave his yell on cue as if nothing was amiss, and the audience and company just froze, in silence. Finally the actor who played Van Helsing blurted out an unforgettable, exasperated ad lib:

“Hit him again, Harker!”

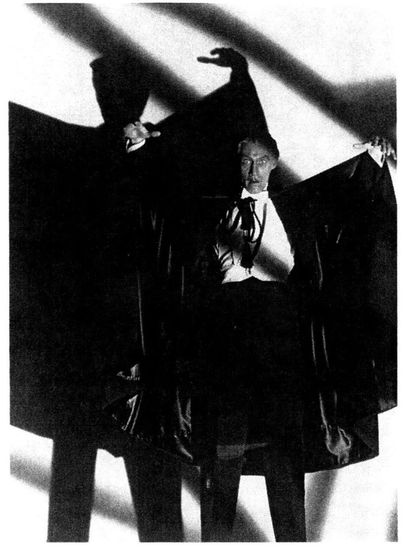

John Carradine in House of Frankenstein (1944) (Author’s collection)

The audience went to pieces, stopping the show for a full two minutes.

Lugosi’s career declined irretrievably after his second film appearance as Dracula. After Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, he would never again have a speaking role for a major studio nor was he able to interest Universal, or any other studio, in a remake of Dracula . Gothic horror had grown passe after the war in a Hollywood now obsessed with giant, radioactive insects. The only straight-faced adaptation of Dracula made anywhere in the world after 1931 was a 1953 Turkish oddity called Drakula Instanbul’da (Dracula in Istanbul), in which Dracula (Atif Kaptan) sported evening clothes like

Lugosi, and a bald head and fangs like Nosferatu. (The fangs were the first in a talking Dracula film.) The opening scenes at Dracula’s castle were fairly faithful to Stoker, including the inaugural screen depiction of Dracula crawling down his fortress wall, as well as Harker’s dramatic attempt to kill the sleeping vampire with a shovel. But when the Count travels to modern Istanbul, the story leaves Stoker in the dust as Dracula fixates on an exotic dancer who keeps his teeth firmly en pointe.

Atif Kaptan in Drakula Instanbul’da (1953) (Courtesy of Ronald V. Borst / Hollywood Movie Posters)

It is perhaps a blessing that Lugosi never remade Dracula, for it is

difficult to know what kind of up-to-date “improvements” 1950s Hollywood would have demanded. A 1951 English stage tour of Dracula was a failure, leaving the actor stranded abroad without enough money for return passage. To raise the cash, he accepted a Dracula-spoofing role in Vampire over London, also known as Mother Riley Meets the Vampire. Mother Riley was the drag persona of actor Arthur Lucan, who had honed the characterization in music halls, on radio and the screen.

The film never found a real audience outside of provincial England, but transvestite associations would follow Lugosi on his return to California. His professional nadir was a three-film involvement with cross-dressing producer/director Edward D. Wood, Jr., often cited as the worst filmmaker of all time for pictures like Glen or Glenda (1954), a transvestite’s bizarre plea for tolerance featuring Wood in the title role with Lugosi providing a demented narration. Next came Bride of the Atom, released as Bride of the Monster (1955), in which the actor is devoured by a rubber octopus which he jiggles himself to provide a threadbare illusion of animation. As the film’s mad scientist, Dr. Eric Vornoff, he delivers a monologue about the inequities that have driven him to the “godforsaken jungle hell” where he cultivates demonic resentment and plots a monomaniacal revenge. It is a quintessential Lugosi moment. Like Joan Crawford, whose rags-to-riches roles mirrored her actual life struggle, Lugosi often played roles that offer a thinly veiled version of his own circumstances. Lugosi’s mad scientists, often double-crossed in business and driven into desperate straits, take on a poignant resonance when viewed as unintentional allegories. The ultimate Bela Lugosi movie would probably center on a blackballed actor who finds a macabre means to wreak his revenge on Hollywood producers.

In April 1955, Lugosi committed himself to a state hospital for the treatment of a decades-long drug addiction that had grown from the use of prescription painkillers. He was seventy-two years old. The public was shocked to see the formerly commanding actor now a drained human shell in a hospital gown, the images of vampire and victim now in disturbing and paradoxical juxtaposition. Was Lugosi the bat … or the bitten? The image of Dracula had become a picture of Dorian Gray.

Lugosi was successfully treated and released, but public sympathy and goodwill did not translate into work. The actor was several decades ahead of his time; drug rehabilitation was not the chic, career-reviving Hollywood ritual it has become today. Lugosi made his last appearance in Ed Wood’s execrable Plan 9 from Outer Space (finally released in 1958). The silent test footage of the actor that is cut into the finished film looks more like outtakes from a home movie than a professional effort. On August 16, 1956, during the making of Plan 9 from Outer Space, Bela Lugosi died of heart failure in Hollywood. Wood finished Plan 9 using his wife’s chiropractor as a stand-in, with a cape covering his face.

An apocryphal story circulated that when Lugosi was found dead, he was holding a copy of the script for a proposed Ed Wood film called The Final Curtain. But it was Dracula’s cape itself that would be Lugosi’s final drapery. Visitors to the funeral home where Lugosi’s corpse was on view found him laid out in full Dracula regalia—cape, tuxedo, medallion. Makeup was applied, the eyebrows darkened, and the hair was dyed to an approximation of its 1931 sheen. Like Dracula himself, who grew younger as he drank more blood, so Bela Lugosi was rejuvenated in death. (Stoker: “There lay the Count, but looking as if his youth had been half renewed, for the white hair and moustache were changed to dark iron-grey; the cheeks were fuller, and the white skin seemed ruby-red underneath; the mouth was redder than ever … .”) Some souvenir photos were taken of the body, and copies of the bereavement card were later offered for sale by mail order by one of Lugosi’s former associates. Interment took place at a Catholic cemetery, which apparently made no objection to the demonic burial vestments.

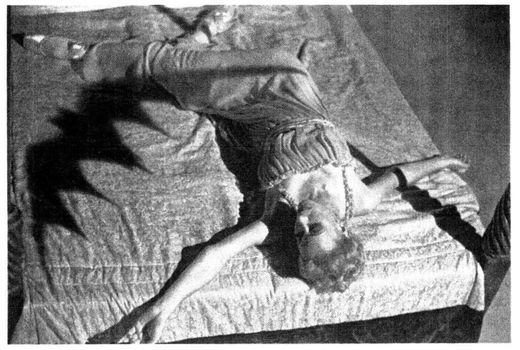

The bat or the bitten? A shockingly emaciated Bela Lugosi was one of the first Hollywood stars to publicize his treatment for substance abuse. (Author’s collection)

Questions of taste aside, it was perhaps the only time in theatrical history in which an actor had been so thoroughly identified with a part that he took it to the grave. (Next to Hamlet, it is probably the role most associated with funereal iconography.) The Dracula mystique was one of Lugosi’s few remaining, if intangible assets; his estate was reported to have been just twenty-nine hundred dollars. Thirty-eight years after his death, he would receive a poignant, if long overdue tribute from the industry that had so little use for him at the end of his life. Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994) earned a best supporting actor Academy Award for Martin Landau, who portrayed Lugosi opposite Johnny Depp as Wood. Although factually inaccurate on many levels, Ed Wood nonetheless sent a bittersweet postmortem valentine to the actor, and Landau’s performance was deservedly honored.

Lugosi died just as Hollywood’s interest in horror and science fiction films was beginning to enjoy a revival. Dracula had already been resurrected a number of times during Lugosi’s lifetime. The film was issued again in 1938 on a double bill with Frankenstein, rereleased by Universal in 1947, and then again by Realart in the early 1950s, and finally to television in 1957 as part of Screen Gems’ immensely popular “Shock Theatre” package of vintage horror films.

The fifties revival was accompanied by the rise of a fascinating fan culture of adolescent and preadolescent males, revolving around the television screenings of old horror films by “horror hosts” in major cities (“Zacherley” in New York, “Vampira” in Los Angeles, and so on) and the rabid consumption of illustrated magazines like Famous Monsters of Filmland, Castle of Frankenstein, and many others. Several

of today’s prominent filmmakers were weaned on these magazines and the activities they generated, including Steven Spielberg, John Landis, John Carpenter, and Joe Dante. Monster culture provided a rite of passage recognizable in anthropological terms, a classic initiation into the mysteries of sex, death, and metaphysics. At the center of monster culture were Dracula and Frankenstein, low-calorie Christ substitutes for the Populuxe age. Both creatures could die and be resurrected, and were inextricably linked with Christian iconography and themes. Both characters reflected aspects of adolescent sexual anxiety. Frankenstein’s fumbling inability to find a mate found its flip side in Dracula’s instantaneous control of women—especially maids, nurses, and mother stand-ins. The sex was symbolic, and, for the moment, safe. As James Warren, publisher of Famous Monsters, told Look magazine, “After us, there’s nothing but Playboy.”

In a suburbanized, plasticized America, monster culture answered a need among male baby boomers for haunted houses instead of tract houses, an ancient, Europeanized structure of meaning. The need would find its most popular apotheosis in two television series, The Munsters and The Addams Family, in which the nightmarish undercurrents of the American nuclear family would be playfully exorcised.

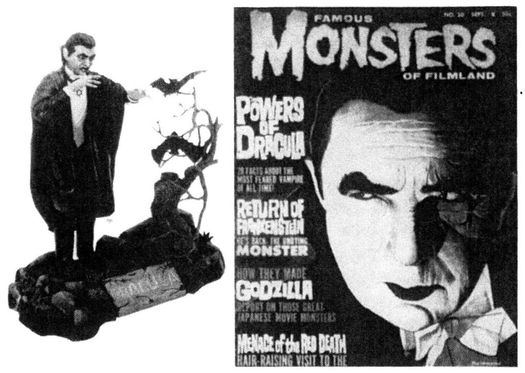

In 1963, Bela Lugosi, Jr., an attorney in Los Angeles, noticed a plastic model kit for sale in toy and drugstores, the package bearing his father’s image, eyes blazing, beckoning children to come forward and buy. The model kit, manufactured by Aurora Plastics, contained component parts that could be assembled into a miniature statue of Count Dracula in a “hypnotic” stance that could be displayed and admired in the bedrooms of young boys. Model planes, then model dinosaurs … why not, then, model blood-sucking vampires?

Lugosi soon learned that the model kit was not the only place his father was making a postmortem appearance as Dracula. When he discovered a paint-by-number kit on sale at a local drugstore, he requested to see copies of his father’s contracts at Universal. After studying the documents, he retained the Los Angeles attorney Irwin O. Spiegel, to represent himself and Hope Lininger Lugosi (the actor’s fifth wife and widow) in an action against Universal. Their complaint alleged that Bela Lugosi’s 1930 contract with Universal for Dracula had granted the studio the use of the actor’s likeness only to advertise and publicize the film, reserving all other commercial uses

of Lugosi’s likeness to the actor himself. The rights to his likeness were held by the plaintiffs to be tangible property to which they were entitled as Lugosi’s heirs. In entering into commercial licensing arrangements, Universal had, the Lugosis claimed, “damaged, diluted, and impaired” the value of their own implied rights. They sought minimum damages of twenty-five thousand dollars. Universal’s licensing activities had been rather extensive. Henry Irving—presumably at Bram Stoker’s insistence—had imprinted his likeness as Mephistopheles on crackers to drum up business in the towns he toured. But Irving’s character was a pale commercial spectre indeed compared to its descendent, Count Dracula. There was, apparently, almost no kind of consumer product or novelty that could not be enhanced by Lugosi’s presence as the vampire. Among the licensed items featuring Lugosi’s screen image as Dracula were children’s phonograph records, plastic toy pencil sharpeners, greeting cards and talking greeting cards, plastic model figures, T-shirts, sweatshirts and patches, rings and pins, monster old-maid card games, soap and detergent products, Halloween costumes and masks, enlargograph sets and kits, target games, picture puzzles, mechanical walking toys, ink-on transfers, trading cards, Halloween candy and gum, comic books, self-erasing magic slates, cutout paper dolls and books, “monster mansion” vehicles, wax figurines, candy dispensers, transparencies, kites, calendars and prints, sliding-square puzzle games, children’s and ladies’ jewelry, belts and belt buckles, wall plaques, wallets, juvenile luggage, “bike buddies” (a novelty in the shape of a monster head on a spring device, to be attached to a bicycle handlebar), animated flip books, lapel buttons, photo printing kits, advertising campaigns, stirring rods and spoons, toy horoscope viewers, junior high school English textbooks, five-cent candy, two-for-one-cent taffy candy, hard-candy cigarettes, tattoo transfers used on inner wrappers of bubble gum, decals, printed vending machine gumballs, filmstrips, and hors d’oeuvres accessories.

Dracula toys and model kits were popular pastimes for baby boomers in the early 1960s. Famous Monsters of Filmland was the house organ of youthful monster culture. (Author’s collection)

In the initial case heard by the Superior Court of Los Angeles County, the Lugosis argued that Universal had not licensed a generic Dracula character. The studio had cast other actors of distinctive appearance as Dracula, notably John Carradine and Lon Chaney, Jr., but had made no attempt to merchandise their images. “The essence of the thing that Universal licensed … was the uniquely individual likeness and appearance of Bela Lugosi,” the suit maintained. Lugosi’s 1930 agreement with Universal had contained the following clause: “The producer shall have the right to photograph and/or otherwise produce, reproduce, transmit, exhibit and exploit in connection with the said photoplay all of the artist’s acts, poses, plays and appearances of any and all kinds hereunder … . The producer shall likewise have the right to use and give publicity to the artist’s name and likeness, photographic or otherwise … in connection with the advertising and exploitation of said photoplay.”

The Lugosis argued that the clause clearly retained all rights of exploitation except for the direct promotion of the film Dracula, and cited the repetition of the phrase “in connection with.” Cocktail accessories could hardly be considered advertising “in connection with” a film not even in general release. Universal maintained the opposite: since there had been no specific limitation expressly stated, Universal’s

right of exploitation was, therefore, limitless. Furthermore, they argued, Lugosi’s right of likeness ended upon his death. Likeness was not a transmissible asset.

The issues raised by both sides were compelling, and many without precedent.

The public records of the court proceedings make for interesting reading, both for the legal issues at hand, as well as for their subtext. Like the actors in the play, wrestling with the empty cape, the legal players were finding the vampire to be, once more, maddeningly elusive. Who—or what—was the essence of Dracula? Where was Dracula? In the costume, in the contract, in the fraction of a millimeter of greasepaint that the actor wore in the role?

Lugosi, in fact, wore almost no makeup at all in Dracula, his stage appearance being naturalized for the film. Nonetheless, one witness for Universal went so far as to state that even though he recognized Bela Lugosi, the actor, he found Lugosi unrecognizable in the role of Dracula (the vampire, one might add, has always had the power to cloud men’s minds). Universal’s other horror characters—the Frankenstein monster, the Wolf Man, and the Mummy, for instance—were totally original creations of the studio that buried the actors beneath grotesque makeup concocted by their resident makeup artist, Jack Pierce. Dracula was also unique in having originated in another medium. Universal acquired the film rights to Dracula, but not the theatrical rights. (The play is still frequently produced, with the character described and costumed in the same cape, costume, makeup, and accent that Lugosi popularized on stage and screen. When Frank Langella played the role on Broadway in 1977, Universal was not a partner to the production, and when the studio remade the film with Langella, the stage producers were similarly not involved in the movie.)

The Lugosi lawsuit was groundbreaking in its claim that, while the late actor never commercially licensed his likeness during his lifetime, the unused potential was a form of real property, descendible to his heirs. In a January 31, 1972, memorandum opinion, superior court judge Bernard S. Jefferson concurred, and ruled for the plaintiffs. Lugosi’s contract, Jefferson wrote, “by express language, limits the producer’s right.” The defendant’s contention that “the possibility that the photoplay might be exhibited on television” rendered its merchandising activities a form of advertising was “untenable and

unacceptable.” Jefferson made special note of the fact that Universal had obtained Lugosi’s written consent to use a wax dummy of the character in the 1936 film Dracula’s Daughter, in which Lugosi himself did not appear. Wrote Jefferson, “If plaintiff’s employment by defendant as Count Dracula in the movie, Dracula, had conveyed to defendant the right to portray Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula apart from his appearance in the movie, Dracula, it would not have been necessary for defendant to obtain Bela Lugosi’s written consent … .”

Oddly, in a point never raised in the trial, the wax dummy in Dracula’s Daughter was a generic prop bearing no resemblance to Lugosi at all. Universal had, in effect, obtained Lugosi’s permission to use the character, and didn’t bother to re-create his likeness.

Jefferson ruled that the Lugosis were entitled to recover damages arising out of each of the licensing agreements within two years of February 3, 1966, due to the applicable statute of limitations. The interlocutory judgment was filed on April 21, 1972, calling for an accounting of damages. A final judgment by the superior court came more than two years later, on July 9, 1974. The Lugosis were awarded the sum of $53,023.23, plus accumulated interest for a total award of $72,993.86.

Lugosi v. Universal Pictures had by that time lasted longer than Florence Stoker’s campaign against Nosferatu. And, like all things both legal and Draculean, the final word had yet to be heard.

Universal appealed the superior court ruling, restating its assertion that Lugosi had portrayed Dracula only as an actor for hire and retained no rights in the character as presented to the public by Universal. “It is adroit juggling indeed to transpose Lugosi from hired actor to exclusive owner-in-perpetuity of the character portrayed by him in another’s copyrighted photoplay,” the defendant claimed. Universal also found fault with many of the trial court’s conclusions in regard to its accounting of Dracula-related merchandising.

The district court of appeals agreed, and overruled the trial court’s decision. Since Lugosi had created no tangible property or merchandising contracts, no rights could be transmitted to his family. Upon his death, his personality entered into the public domain and could be exploited by anyone for any legitimate commercial purpose. Given the long history of Dracula in the courts, preceding even Lugosi, or Universal, the case could not be over. And it wasn’t.

The Lugosis petitioned the California Supreme Court, citing the numerous larger issues at stake, in addition to their own claims. The effects of the district court opinion, they held, “unfairly discriminate in favor of the motion picture producers as an entrepreneurial class to the detriment of the surviving families of actors and other creators of artistic and intellectual property.” An actor like Bela Lugosi, they maintained, had protectable rights with a clear basis in common law. The plaintiffs noted the disparity between the parties to a contract: the studio’s rights were automatic and did not need to be exercised in order to be enforced; an artist was required to actively exploit retained subsidiary rights in order to perpetuate them. The producer’s rights were (by metaphorical implication) almost undead, “of potentially infinite duration not limited or measured by the life of the actor, whereas the artist’s retained subsidiary rights cannot endure beyond his lifetime.”

On December 3, 1979, the California Supreme Court upheld the appeals court decision. “Lugosi’s right to create a business, product or service of value is embraced in the law of privacy and is protectable during one’s lifetime but it does not survive the death of Lugosi,” the court ruled.

A concurring opinion was filed by Justice Mosk: “Factually, not unlike the horror films that brought him fame, Bela Lugosi rises from the grave 20 years after death to haunt his former employer. Legally: his vehicle is a strained adaptation of a common law cause of action unknown either in a statute or case law in California.” It was clear, wrote Mosk, “that Bela Lugosi did not portray himself and did not create Dracula, he merely acted out a popular role that had been garnished with the patina of age … his performance gave him no more claim on Dracula than that of countless actors on Hamlet who have portrayed the Dane in a unique matter.” Mosk added, rather bizarrely, given the facts in the case, that Lugosi had been paid “handsomely” in 1931 terms, and that any limitations the actor wished to place on his employer needed to be specified in the contract, not interpreted after the fact. He raised the spectre of the descendents of George Washington suing the secretary of the treasury for placing Washington’s likeness on the dollar bill, and similar legalistic nightmares.

Chief Justice Rose Bird (who would later lose her position for not being sufficiently bloodthirsty on the issue of capital punishment to suit Californians) filed a lengthy dissenting opinion. She argued that the issue at stake was not solely one of privacy, but publicity, and the fair recognition of an individual’s labor and energy in creating a recognizable public persona. “White this product is concededly intangible, it is not illusory.” The majority opinion, Bird reasoned, insisted on a double standard: the actor’s right of publicity was fragile and would die with him if not exploited, but the same right, if assigned to the undying corporation, could remain dormant indefinitely until circumstances were favorable for exploitation. In Dracula’s words, torn from the stage play: “I go to sleep in my box for a hundred years … .” Time, indeed, was on Dracula’s side when he assumed a corporate mantle.

Lugosi v. Universal Pictures can be read as a kind of postmodernist gothic text as much as a legal document. The horror themes are implicit, but not illusory. We have an actor, his career itself a Faustian parable, his fame dependent on perpetuating a certain contemporary image of the devil. The image drains the actor in a Dracula/Dorian Gray/doppelganger fashion, he dies and is resurrected, his ghost employed to attract and fascinate children for purposes of economic exploitation. Vampirism and consumerism blur; one begets the other. By the 1970s, the corporate entity that controls the actor’s demonic alter ego resides in a black tower risen on the very site that once impersonated Transylvania—a fictive, filmic ritual that both saved and prolonged its corporate life. Conflict arises over the possession and control of the dead actor’s valuable essence. Rituals are performed, dealing with themes of identity, materiality, blood ties, possession, and things that survive death. Obsession ensues.

In the Victorian context, Dracula’s meanings are distinctly sexual. A century later, the metaphors are economic. But Bram Stoker is already ahead of us. Late in his novel, with the Count trapped in commercial Piccadilly, Jonathan Harker takes a literal stab at his peculiar alter ego: “The blow was a powerful one; only the diabolical quickness of the Count’s leap back saved him. A second less and the trenchant blade had shorn through his heart. As it was, the point just cut the cloth of his coat, making a wide gap whence a bundle of

bank-notes and a stream of gold fell out.” Dracula escapes with a handful of money, smashing through a window. And amid the crash and glitter of the falling glass, Dr. Seward discerns an unmistakable sound: gold sovereigns, tinkling musically on the flagstones.

Blood money, if there ever was.

By the late 1950s, the lucrative Dracula franchise had expanded considerably beyond Lugosi’s shadow. In 1956, Hammer Film Productions, a British company founded in the 1930s, proposed a seven-part television serial based on Dracula, but found the issue of rights to the property, and the complicated multiparty agreements between Universal, Florence Stoker, John Balderston, Hamilton Deane, and Charles Morrell to be a tangled, nearly incomprehensible legal web. The studio had no interest in the stage plays and wanted to base its production on the novel alone, but finally was forced to acquire production rights to the whole Universal contract package. Hammer was simultaneously preparing a theatrical feature called The Curse of Frankenstein for Warner Bros., but ran into legal challenges from Universal over the use of the name “Frankenstein.” Hammer, however, held the high hand; Mary Shelley’s 1819 novel and the surname of her antihero were in the public domain throughout the world. Anyone could base a film on it.

Copyright technicalities allowed American-International Pictures, an energetic independent studio specializing in the teen and drive-in market, to legitimately exploit the Dracula name without incurring litigation. Since Stoker’s novel (and, by extension, the name of its title character) were in the public domain in the United States, for stateside release, any film could freely use the name.14 Herman Cohen’s Blood of Dracula had nothing to do with Stoker’s book and didn’t even feature Dracula (just a Transylvanian amulet that might have had something to do with him). It established a winning formula: take a troubled teen with a lot of pent-up rage; stir in an unscrupulous authority figure and a dash of mad science; and, presto, all hell breaks loose. Sandra Harrison stars as a girl whose widowed dad has taken up with an expensive floozie. They ditch her in a private

girls’ academy where a power-crazed science teacher (Louise Lewis) plans, somehow, to upset the male-dominated scientific establishment with a Mr. Wizard—style chemistry set and the spooky amulet. She only succeeds in turning the impressionable Harrison into a small-time serial killer with really big teeth. Blood of Dracula set the template for Cohen’s iconic cult classics I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957). A.I.P. circumvented international copyright issues by calling the film Blood Is My Heritage in England and Blood of the Demon in Canada. In 1958, United Artists released The Return of Dracula, wherein a communist bloc vampire (Francis Lederer) invades the home of a California family in a story that owed more to Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt than to Bram Stoker. To skirt copyright infringement in England, the film was released there as The Incredible Disappearing Man.

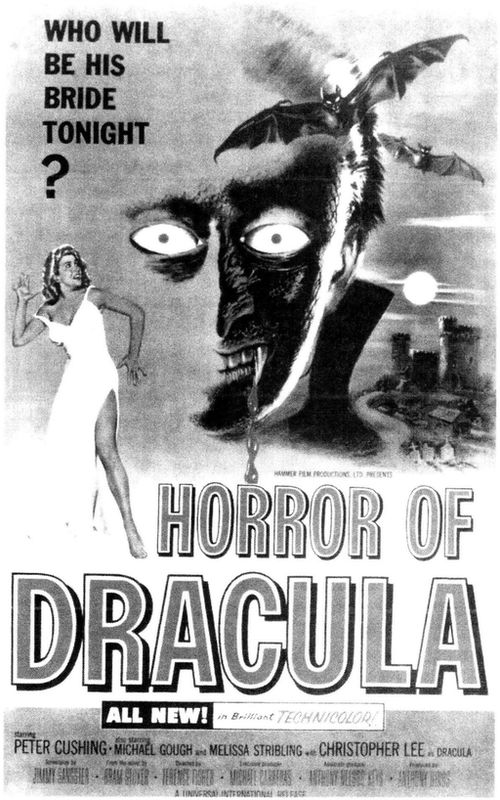

In the meantime, Hammer’s plans for a live television production of Dracula were abandoned. Universal’s final contract terms (agreed upon in early 1958, after a year and a half of wrangling) called for “a first class motion picture, as such term is commonly understood in the motion picture industry, and of first class quality.” Universal financed the production, as Warner had with The Curse of Frankenstein . Directed by Terence Fisher, who would soon become Hammer’s leading avatar of the uncanny, the film would be released as Horror of Dracula in the United States, but retain the title Dracula in the U.K.

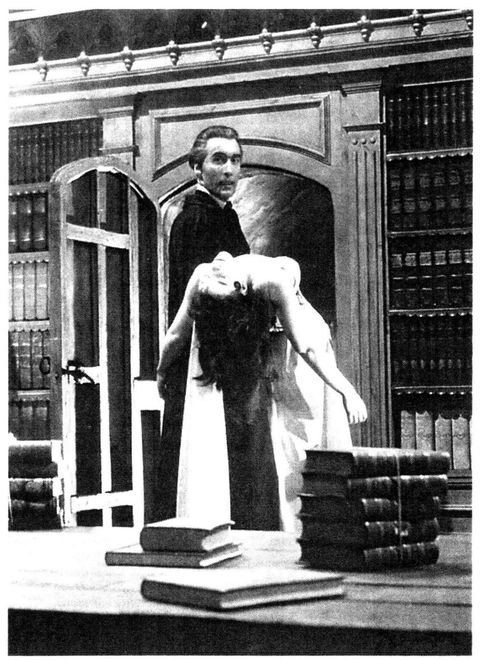

In Curse, the role of Mary Shelley’s stitched-together creature had been played by Christopher Lee, a tall and broodingly handsome actor of Anglo-Italian ancestry who had made one of his first film appearances (however briefly) in Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948).15 In the best tradition of the nineteenth-century actor Thomas Potter Cooke, who played both Frankenstein’s monster and Polidori’s vampire on the stage, Lee was chosen to play the first major screen Dracula of the postwar era. “I had never seen Bela Lugosi’s ‘Dracula,’” recalled Lee. “It was with some understandable doubts that I entered upon this role. Lugosi had made the part his own over a period of many years, his performance was a classic, his name was indelibly associated

with the name of Dracula. I was determined that I would copy nothing that had been done previously … .” Lee maintained that “have always tried to include in my performances what I term the ‘loneliness of evil.’ Despite his actions, there is to me a sadness about Dracula, a brooding, withdrawn unhappiness. He is in this world, but he is not of this world. He is a demon, but above all he is a man.” The screenplay, by Jimmy Sangster, studiously avoided material from the stage versions, but, in its own way, jettisoned as much of Stoker’s novel as Hamilton Deane had. Renfield was eliminated, as was Dr. Seward. The supernatural attributes of vampires were sharply curtailed—bat transformations, for instance, were dismissed as mere superstition, and a quasi-medical rationale for vampirism was proposed. For the first time, Van Helsing utilized Stoker’s device of a recording phonograph to keep his notes. The geographical sweep of the book was entirely dispensed with. Instead of Transylvania and England, the story was now completely set in an unnamed European principality, a bit like the European never-neverlands concocted by Universal for its 1940s monster-fests. Part of the reason was budgetary. Stock costumes could be eclectically mixed and matched, as could stock scenery. But Sangster also shrewdly found ways to circumvent problematic issues in Stoker’s book. In the novel, Jonathan Harker is the protagonist for the first few chapters, but fades into an ensemble of characters as the story progresses. In the Deane and Balderston play, as well as in the 1931 film, he became increasingly ineffectual. Sangster posited that Harker was not the Count’s consulting librarian (given the total collapse of geography, the real estate angle was moot), but instead a vampire hunter already secretly working with Van Helsing (Peter Cushing, who would make this part his own in this and three subsequent films) to defeat Dracula. The three vampire wives are condensed into one, memorably played by the (wonderfully named) Valerie Gaunt, who pretends to ask for Harker’s help in escaping Dracula’s clutches, but only to get a good angle at his jugular.

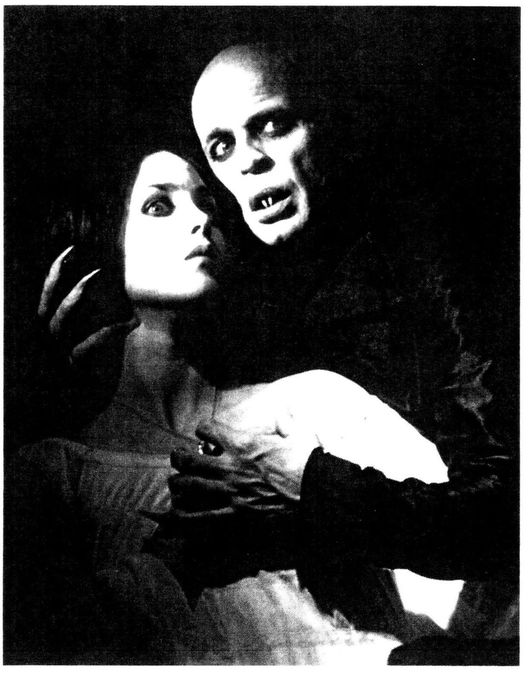

The next scene is one of the great entrances in the history of horror films, as Dracula suddenly appears to wrest his bride from Harker. He thrusts his enraged face into the camera for a full close-up, his eyes insanely bloodshot (the first use of red contact lenses in a Drac-ula

film), his canine fangs fully extended and practically throbbing, his mouth dripping with great gouts of Technicolor blood. Nothing like this had ever been seen before on-screen. Audiences had always been told about blood-sucking, and bite marks, and other habits and signs of vampires, but the visual treatment had always been fairly reserved. In the 1931 film, for instance, the only representation of blood had been a single drop on Renfield’s finger. The actual bite was discreet, traditionally hidden by an enveloping cape. But Hammer had thrown down a gauntlet, ushering in a new age of visceral bluntness on-screen.

Christopher Lee and Valerie Gaunt in Horror of Dracula (1958), the film that brought the vampire genre roaring back to life (Photofest)

When Hammer’s Dracula made its debut in Piccadilly, queues reportedly stretched for a quarter mile. The critics were not so enthusiastic. “A sane society cannot stand the posters, let alone the films!” wrote one critic of the Hammer production in the British film magazine Sight and Sound. The Daily Worker echoed the socialist disdain for Nosferatu a quarter of a century earlier. “From the moment Dracula appears, eyes bloodshot, fangs dripping with blood, until his final disintegration into a crumbling, putrescent pile of human dust, this film disgusts the mind and repels the senses,” wrote critic Nina Hibbin, judging the whole thing to be “a degradation of cinema entertainment.” Hammer wasn’t trying to degrade the movies as much as it was searching for a formula to lure young audiences away from the encroaching menace of television, and back into the movie house. Monster movies in the fifties had already succeeded at the box office by providing a sensational novelty unavailable on the small screen. The original Dracula and Frankenstein films were just making their television debuts, and they were pale ghosts indeed compared to Hammer’s lurid new recipe of heaving bosoms, drizzling blood, and erectile fangs. The gambit worked. It has been claimed that Horror of Dracula, produced for about two hundred thousand dollars, ended up having the greatest cost-to-profit ratio of any film ever produced in Great Britain.

Despite the picture’s international success, it would be two years before Universal financed another Hammer Dracula picture. Due to Christopher Lee’s unavailability, it would be a Dracula film in name only. The Brides of Dracula, released in 1960, reveals its bait-and-switch strategem from the outset, as Peter Cushing informs the audience in voiceover: “Count Dracula was dead. But his disciples lived on.”

The film, however, was no cynical rip-off, but rather an inventive detour from the main Dracula storyline that would become a cult favorite. Directed by Terence Fisher from a screenplay by Jimmy Sangster, The Brides of Dracula turns on a Suddenly, Last Summer-like premise: a dragon-lady baroness (the peerless Martita Hunt, who

played Miss Havisham in David Lean’s Great Expectations in 1946) entices young women to her castle to provide nourishment to her beautiful, captive vampire son, Baron Meinster (David Peel). The baroness is guilt-stricken about her son’s predicament. Somehow, she fostered his delicate condition by indulging a taste for decadent friends and discreetly unspecified, but nonetheless “wicked” games. (Whether or not these games were played directly with Count Dracula is never addressed.) The Oedipal tension reaches a climax when the baroness is finally neck-penetrated by her son, then cardio-penetrated by Peter Cushing’s Van Helsing. The thinly veiled Freudian currents were picked up by the reviewer for the London Evening Standard, who noted, disapprovingly, that the golden-haired male vampire “capitalises on current fashion by resembling Oscar Wilde’s Bosie with fangs.” Actor Peel may have had more in common with another Wildean personage; at the age of forty, Peel’s ability to play a role roughly half his age immediately brings to mind The Picture of Dorian Gray. Reviled by many reviewers when it first appeared (the London Observer called it “a ludicrous monstrosity”), The Brides of Dracula is now widely considered a minor classic, prefiguring the themes of sexual ambiguity more recently expanded upon by writers like Anne Rice.

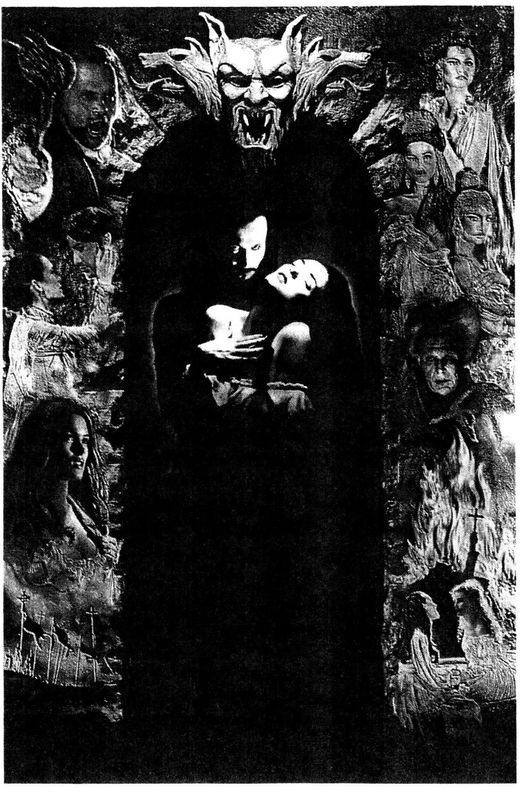

“A sane society cannot stand the posters, let alone the films.” Poster for Horror of Dracula (Author’s collection)

Universal ultimately sold the rights to Horror of Dracula to Warner Bros./Seven Arts, which re-released it on a double bill with Curse of Frankenstein in 1965, but neither studio would participate in Hammer’s next Dracula outing, Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), again directed by Terence Fisher and this time released by Twentieth Century-Fox.

Both the script and first cut of the film created problems with the Motion Picture Association of America and the British Board of Film Censors. To resurrect Dracula, the screenplay by John Sansom (a pseudonym of Jimmy Sangster, who could not have been happy with the scrapping of all his Dracula dialogue) introduced a previously unknown servant to the Count named Klove (played by Philip Latham) who has carefully preserved the master vampire’s ashes. When a pair of young couples foolishly seeks refuge in the castle, he sees a chance to facilitate his master’s comeback. He kills one of the husbands for his blood, which, mixed with the ashes, reconstitutes Dracula like a satanic pot of Sanka.

The MPAA warned Hammer that the resurrection scene as written

was unacceptable in America. “The business of Klove decapitating Alan and the subsequent scene showing the torrents of blood pouring into the coffin, together with Klove’s throwing of Alan’s head aside, is simply too sickening to be approved.” The BBFC had its own issues. “We have always taken the line that we should not see stakes actually going into vampires,” the board told Hammer, evidently forgetting the graphic staking of Lucy in Hammer’s first picture. “Here in Scene 222 we see it in silhouette. We do not mind stakes being hammered provided that the point cannot be seen going into the body, and this applies as much to silhouette as a straight shot.” Hammer made a few concessions, demoting the decapitation to a mere throat slashing. The BBFC twice demanded cuts in the finished film, insisting that the resurrection scene was still too much. “There must be no shot of Alan being slashed … no shot of blood pouring from him and no shot of blood congealing in the sarcophagus.” The board apparently lacked sufficient bite, for the released film contained no less than three separate shots of blood copiously infusing Dracula’s ashes. As for the admonition against a silhouetted staking, Hammer brazenly replaced it with a bloody close-up of a stake insertion. The board objected again: “[T]here must be no shot of the stake being driven into her and of blood spurting from the wound.” But Hammer prevailed, and the stake, and the spurt, remained, at least in the American version.

Hammer’s disdain for authority was reflected in its youthful audiences, coming of age in a particularly rebellious (and gruesome) decade. The Hammer Dracula films reflected and refracted the cultural tensions of both the Vietnam era and the sexual revolution. Their title character, after all, was already a classic symbol of bloody international aggression. But to audiences in the sixties and seventies, he came to represent something else: an anti-authoritarian authority figure, a destabilizing force who could always be depended upon to subvert the stuffy status quo and bring vampire excitement into corseted, middle-class lives. In film after film, Lee’s ever-more ingenious resurrections were typically greeted with wild applause by his fans. In the Hammer films, vampirism amounted to a coded counterculture of sexual liberation and female empowerment. In Dracula: Prince of Darkness, Carol Shelley as Helen, the repressed wife of throat-slashed Alan, is glamorously transformed into an assertive,

self-possessed female vampire, only to find herself pursued by religious patriarchs unwilling to tolerate such a “new woman.”

Hammer followed Dracula, Prince of Darkness with Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968), with a memorably fang-in-cheek poster showing a comely neck sporting two Band-Aids bandages and the comment OBVIOUSLY under the main title. Metaphors of emancipated womanhood began to wane, and Hammer’s heroines and antiheroines took a sharp turn toward the bimbo-esque. In Dracula Has Risen, for instance, the vampire sends a bat emissary to remove a crucifix hanging between his intended victim’s breasts, and the bat lingers, perhaps a bit distracted by all the scenery.

The next year saw Taste the Blood of Dracula, in which overbearing and hypocritical Victorians imbibe the titular fluid. Although Christopher Lee often waxed eloquently about the complexities of the character, aside from the opening scenes of Horror of Dracula, the Hammer scripts treated the character as little more than a lip-curling, fang-revealing, red-eyed menace. In 1970, fans could see Lee’s Dracula gnashing his teeth (no doubt discomfited by those scripts, not to mention the massive contact lenses) in two films: Hammer’s Scars of Dracula, which had no storyline connection to any of the other Hammer efforts; and an ambitious (if woefully underbudgeted) Franco-Spanish production called Count Dracula, which finally allowed Lee to portray the Count in a style Hammer would never allow. The original novel was fairly carefully followed (at least for the Transylvanian scenes). Lee wore a drooping mustache, through which he intoned dialogue that at least approximated Stoker’s. Herbert Lom played Van Helsing and Klaus Kinski (later a Dracula himself) took the part of Renfield. But the threadbare production values sank the film. As Variety noted, “Yelping German shepherd dogs substitute for wolves, scenes are set in Budapest instead of England, and not a string of garlic appears … .”

In 1972, Boston University historians Raymond T. McNally and Radu R. Florescu published In Search of Dracula, the first detailed account of the life and times of Wallachian prince Vlad Tepes (1431-1476), the historical figure who actually bore the name Dracula and displayed behavior to fit. Tepes’s favorite method of dispatching his enemies was by impalement, which has led many to believe that

vampire-staking has some essential connection to this historical personage. In actuality, Vlad was never linked to vampire superstitions, and his specific technique of impalement—via the rectum, with victims hoisted for long, excruciating, gravitational deaths—was meant to terrify enemies, not to keep the dead in their graves. Though the historical record more than suggests a world-class psychopath, Vlad is commemorated as a Romanian national hero, who effectively warded off incursions by the Turks.

In Search of Dracula annoyed many scholars, who knew that Stoker’s research into Vlad was tissue-thin, and in no way “inspired” the novel. But In Search of Dracula was a bestseller, one that legitimized the subject topic of Dracula and vampires for a media establishment previously disposed to treat the whole topic as a joke. Of the two authors, McNally was a flamboyant, media-savvy showman, who aggressively worked the lecture and talk-show circuit, never hesitating to wear a high-collared cape if it drew audiences and reporters to his work.

American television turned to both the Stoker novel and the discoveries of McNally and Florescu for a 1973 prime-time adaptation starring Jack Palance. The producer was Dan Curtis, whose phenomenally successful soap opera Dark Shadows had already proved there to be an enormous market for vampirism among daytime television viewers. At night, it can be assumed, they would be all the more receptive. Dark Shadows had included a plotline about a New England vampire, Barnabas Collins, who pursues a young woman he believes to be the reincarnation of his lost love. It was a motif already well-established by Boris Karloff’s The Mummy (1933) and its many sequels, but had never before been exploited for a vampire melodrama. Richard Matheson, who scripted Curtis’s production, titled Bram Stoker’s Dracula, cast Lucy as Vlad’s long-lost betrothed, and, for the first time, depicted a lovesick Dracula who actually wept.

In Our Vampires, Ourselves (1995), Nina Auerbach noted that

The 1970s was a halcyon decade for vampires, one in which they not only flourished, but reinvented themselves. Hammer vampires, young and swollen with desire, had teased pompous authorities before retreating into solemnity and the old roles. Vampires in the 1970s become authorities. Hovering between animal and angel, they are paragons of emotional complexity and discernment, stealing from Van Helsing

the role of knower but adding a tenderness and ineffable sorrow human beings have become too monstrous to comprehend.

Not all the seventies Dracula incarnations were emotionally complex, but the new romanticism considerably expanded the market for other kinds of vampire entertainment and exploitation. Hammer Films started a second vampire franchise based on Le Fanu’s Carmilla; the first installment, The Vampire Lovers (1970) introduced topless lesbian vampires, with the favored penetration site located somewhat lower than the jugular. By the end of the decade, Transylvania’s favorite son went hardcore with Dracula Sucks (1979), featuring porn superstars Jamie Gillis, Annette Haven, and John Holmes, which appropriated most of its dialogue from the 1931 Universal film—not that its intended audience was in any way paying attention to the dialogue.

Despite relaxed media constraints, Dracula in the seventies wasn’t always blatantly sexual, and reached out to the prepubescent set in less provocative ways. On television’s Sesame Street, the Count emerged as one of Jim Henson’s most durable Muppet characters, instructing children in numerical literacy (i.e., “counting”) with Transylvanian intonations of “Vun, two, three!” Count Chocula materialized as a breakfast cereal in 1971, eliciting only droll amusement until 1987, when a new box design drew immediate complaints from Jewish groups. In an odd episode inadvertently underscoring the creeping anti-Semitism of Stoker’s original story, General Mills’s redesign rendered Bela Lugosi’s six-pointed medallion as a dead ringer for the Star of David.

Count Chocula was the first coinage of a trademark or title utilizing the suffix “ula” as shorthand for vampire; just as “gate” would become the favored suffix for political scandals after the seventies. Following were Bunnicula (a 1979 children’s book about a vegan-vampire bunny rabbit who sucks the juice and color from carrots); Japula (from Tokyo, 1971); Spermula (soft core erotica from France, 1975); Gayracula (gay porn, 1983); Rockula (set in the music world, 1990), and many others.

The most endearing and enduring of these ula-lations was Blacula, a 1972 film introducing the world’s first vampire of (rather than in) color. Shakespearean actor William Marshall played the African prince Mamuwalde, condemned to undeath by Count Dracula himself

(Charles MacCauley), who, we learn, once dabbled in the slave trade. A pair of gay interior decorators bring Mamuwalde’s coffin to Los Angeles with a shipment of Transylvanian antiques, and Blacula sets upon a bloody quest for his lost but reincarnated African love. The film ends in a sewage treatment plant, the kind of unfortunate script choice that can lead reviewers to say very rude things. A sequel, Scream, Blacula, Scream arrived the following year.

Paul Morrissey’s Blood for Dracula (1973; retitled for American consumption as Andy Warhol’s Dracula) reflected the challenges faced by Dracula in a world of shifting sexual mores. Virgins are no longer readily available in his homeland, and the weakened and starving Count (Udo Kier) migrates to an Italian village in the mistaken belief that a Catholic country will enforce chastity among its young women. Alas, this is not the case, and he ends up vomiting contaminated blood. “My body can’t take it any more!” he wails. “The blood of these whores is killing me!” The febrile, wheelchair-bound vampire must also undergo Marxist rants from Warhol’s working-class “superstar” Joe Dallesandro, delivered in deadpan Brooklynese. The most memorable sequence appears under the opening titles, as the aged Dracula rejuvenates himself with black hair dye, primping before a mirror like a drag queen, fangs discreetly protruding through his lip gloss.

Dracula invaded the world of comic books with Marvel Comics’s Tomb of Dracula, which had a successful run between 1972 and 1979. Since Dracula’s transformative powers overlapped with those of established Marvel superheroes, Dracula dug ever deeper into core popular culture.

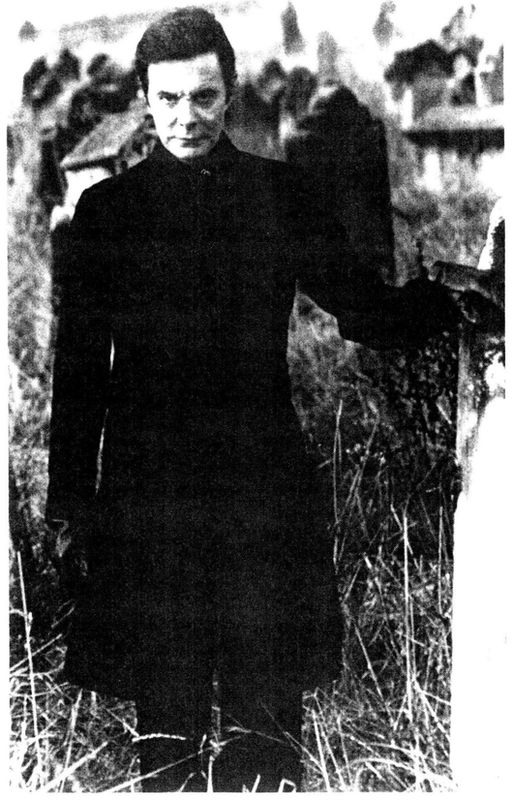

The Deane and Balderston play was successfully revived on Broadway in 1977, in a production with Frank Langella in the lead, briefly replaced by David Dukes, and succeeded by Raul Julia, Jeremy Brett, and Jean Le Clerc. The production was conceived as a three-dimensional Edward Gorey cartoon, with Gorey himself designing the sets and the costumes. It had been tried out as a small-scale summer stock production at the Nantucket Stage Company, near the artist’s home on Cape Cod. Langella had already played Dracula in a more conventional production at the Berkshire Theatre Festival in 1967.

Walter Kerr, writing in the Sunday New York Times, described the effect of Gorey’s sets and costumes:

The curtain rises not on a room but on a cartoon, a massive two-dimensional pen-and-ink sketch carrying us upward like a beehive tomb at Mycenae; and everywhere in its intricate strokes lurk the outline of bats’ wings: bats’ wings worked into the fireplace mantle, bats’ wings worked into the cornices and pediments, bats’ wings worked into the upholstered blue-gray furniture. When heroine Lucy comes on, dancing to an ancient radio and sipping from the blood-red contents of her wineglass, we discover—as she extends her arms—that her gown drapes into bats’ wings, too.

Frank Langella in the 1977 Broadway revival of Dracula (Photofest)

Such aggressive stylization, of course, amounted almost to an extended deconstruction of the play rather than a performance. But under Dennis Rosa’s deft direction, the campy, ironic staging clicked. In the 1927 incarnation, Bela Lugosi broke the “fourth wall” by addressing the end of one line (“I love England and the great London … so different from my own Transylvania where there are so few people and so little opportunity.”) directly to the audience with a knowing smile. In the revival, Langella repeatedly exchanged conspiratorial glances with the audience. Since Dracula’s role as written is fairly slight, additional dialogue and business was added to bolster Langella’s star turn. The line “I never drink … wine” was lifted from the 1931 film (it had never been part of the play), and Dracula’s bloody breastfeeding of his victim (here presented as intensely erotic, performed in a bat-shaped bed swathed in silver lamé) was added to the second-act climax. Once more, Dracula gave the audience a sudden, direct glance, as if aware he was being watched, before completing his bite. Following that scene on opening night, a woman in the audience was reported to have blurted out, “I’d rather spend one night with Dracula dead, than the rest of my life with my husband alive.”

Like the Broadway production fifty years earlier, the 1977 revival received decidedly mixed reviews—all of which did nothing to slow the public’s stampede to the box office. The New York Times daily critic Richard Eder declared the production “elegant” yet “bloodless.” “Mr. Langella is a stunning figure as Dracula,” Eder wrote, “but he notably lacks terror.” Dracula, in Eder’s judgment, “comes to us with a stake in its heart, beyond real revival although capable of useful adornment.”