When a Wal-Mart moves into a small town, the environment changes for every retailer in that town. A “10X” factor has arrived. When the technology for sound in movies became popular, every silent actor and actress personally experienced the “10X” factor of technological change. When container shipping revolutionized sea transportation, a “10X” factor reordered the major ports around the world.

Reading the daily newspapers through a “10X” lens constantly exposes potential strategic inflection points. Does the wave of bank mergers that is sweeping the United States today have anything to do with a “10X” change? Does the acquisition of ABC by Disney or Time Warner’s proposed merger with Turner Broadcasting System have anything to do with one? Does the self-imposed breakup of AT&T?

In subsequent chapters, I will discuss common reactions and behavior that occur when strategic inflection points arise, as well as approaches and techniques for dealing with them. My purpose in this chapter is to sweep through a variety of examples of strategic inflection points drawn from different industries. By learning from the painful experience of others, we can improve our ability to recognize a strategic inflection point that’s about to affect us. And that’s half the battle.

I’ll largely use the framework of Porter’s competitive analysis model, as most strategic inflection points originate with a large “10X” change in one of the forces affecting the business. I will describe examples that are triggered by a “10X” change in the force of the competition, a “10X” change in the technology, a “10X” change in the power of customers, a “10X” change in the power of suppliers and complementors, and a “10X” change that is due to the imposition or the removal of regulations. The pervasiveness of the “10X” factor raises the question, “Is every strategic inflection point characterized by a ‘10X’ change? And does every ‘10X’ change lead to a strategic inflection point?” I think for all practical purposes the answer to both of these questions is yes.

There’s competition and there’s megacompetition, and when there’s megacompetition—a “10X” force—the business landscape changes. Sometimes the nature of the megacompetition is obvious, and the story of Wal-Mart that follows will give an example of that. Sometimes the megacompetition sneaks up on you. It doesn’t do business the way you are used to having business done, but it will lure your customers away just the same. The story of Next will give an example of that.

From the standpoint of a general store in a small town, a Wal-Mart store is competition. So were the other general stores that it previously had to compete with. But Wal-Mart comes to town with a superior “just-in-time” logistics system, with inventory management based on modern scanners and satellite communications; with trucks that go from store to hub to store continuously replenishing inventories; with large-volume-based purchase costs, systematic companywide training programs, and a finely tuned store location system designed to pinpoint areas where competition is generally weak. All this adds up to a “10X” factor compared to the other competition the store previously had to face. For a small-town general store, once Wal-Mart moves to town, things will have changed in a big way.

A far superior competitor appearing on the scene is a mandate for you to change. Continuing to do what worked before doesn’t work anymore.

What would work against a Wal-Mart? Specialization has a good chance. In-depth stocking, serving a particular market segment, as Home Depot, Office Depot, Toys “я” Us and similar “category killers” are doing, can work to offset the overall imbalance of scale. So can customized service, as Staples is implementing through an in-depth computerized customer database. Alternatively, so might redefining your business to provide an environment, rather than a product, that people value, like the example of an independent bookstore that became a coffeehouse with books to compete with the chain bookstores that brought Wal-Mart-style competitive advantages to their business.

When Steve Jobs cofounded Apple, he created an immensely successful, fully vertical personal computer company. Apple made their own hardware, designed their own operating system software, and created their own graphical user interface (what the customer sees on the computer screen when he or she starts working with the computer). They even attempted to develop their own applications.

When Jobs left Apple in 1985, he set out, for all intents and purposes, to recreate the same success story. He just wanted to do it better. As even the name of his new company implied, he wanted to create the “Next” generation of superbly engineered hardware, a graphical user interface that was even better than Apple’s Macintosh interface and an operating system that was capable of more advanced tasks than the Mac. The software would be built in such a way that customers could tailor applications to their own uses by rearranging chunks of existing software rather than having to write it from the ground up.

Jobs wanted to tie all of this—the hardware, the basic software and the graphical user interface—together to create a computer system that would be in a class by itself. It took a few years, but he did something close to that. The Next computer and operating system delivered on basically all of these objectives.

Yet while Jobs was focusing on an ambitious and complex development task, he ignored a key development that was to render most of his efforts futile. While he and his employees were spending days and nights developing the superb sleek computer, a mass-produced, broadly available graphical user interface, Microsoft Windows, had come on the market. Windows wasn’t even as good as the Mac, let alone the Next interface, and it wasn’t seamlessly integrated with computers or applications. But it was cheap, it worked and, most importantly, it worked on the inexpensive and increasingly powerful personal computers that by the late eighties were available from hundreds of PC manufacturers.

While Jobs was burning the midnight oil inside Next, in the outside world something changed.

When Jobs started developing Next, the competition he had in mind was the Mac. PCs were not even a blip on his competitive radar screen. After all, at that time PCs didn’t even have an easy-to-use graphical interface.

But by the time the Next computer system emerged three years later, Microsoft’s persistent efforts with Windows were about to change the PC environment. The world of Windows would share some of the characteristics of the Mac world in that it provided a graphical user interface, but it also retained the fundamental characteristics of the PC world, i.e., Windows worked on computers that were available anywhere in the world from hundreds of sources. As a result of fierce competition by the hundreds of Computer manufacturers supplying them, these computers became far more affordable than the Mac.

It was as if Steve Jobs and his company had gone into a time capsule when they started Next. They worked hard for years, competing against what they thought was the competition, but by the time they emerged, the competition turned out to be something completely different and much more powerful. Although they were oblivious to it, Next found itself in the midst of a strategic inflection point.

The Next machine never took off. In fact, despite ongoing infusions of investors’ cash, Next was hemorrhaging money. They were trying to maintain an expensive computer development operation, in addition to a state-of-the-art software development operation, plus a fully automated factory built to produce a large volume of Next computers—a large volume that never materialized. By 1991, about six years after its founding, Next was in financial difficulties.

Some managers inside the company had advocated throwing in the towel in hardware and porting their crown jewel to mass-produced PCs. Jobs resisted this for a long time. He didn’t like PCs. He thought they were inelegant and poorly engineered, and the many players in the industry made any kind of uniformity hard to achieve. In short, Jobs thought PCs were a mess. The thing is, he was right. But what Jobs missed at the time was that the very messiness of the PC industry that he despised was the result of its power: many companies competing to offer better value to ever larger numbers of customers.

Some of his managers got frustrated and quit, yet their idea continued to ferment. As Next’s funds grew lower and lower, Jobs finally accepted the inevitability of the inelegant, messy PC industry as his environment. He threw his weight behind the proposal he had fought. He shut down all hardware development and the spanking new automated factory, and laid off half of his staff. Bowing to the “10X” force of the PC industry, Next, the software company, was born.

Steve Jobs is arguably the founding genius of the personal computer industry, the person who at age twenty saw what in the next decade would become a $100 billion worldwide industry. Yet ten years later, at thirty, Jobs was stuck in his own past. In his past, “insanely great computers,” a favorite phrase of his, won in the market. Graphical interfaces were powerful differentiators because PC software was clunky. As things changed, although many of his managers knew better, Jobs did not easily give up the conviction that had made him such a passionate and effective pioneer. It took facing a business survival situation for reality to win over long-held dogmas.

Technology changes all the time. Typewriters get better, cars get better, computers get better. Most of this change is gradual: Competitors deliver the next improvement, we respond, they respond in turn and so it goes. However, every once in a while, technology changes in a dramatic way. Something can be done that could not be done before, or something can be done “10X” better, faster or cheaper than it would have been done before.

We’ll look at a few examples that are clear because they are in the past. But even as I write this, technological developments are brewing that are likely to bring changes of the same magnitude—or bigger—in the years ahead. Will digital entertainment replace movies as we know them? Will digital information replace newspapers and magazines? Will remote banking render conventional banks relics of the past? Will the wider availability of interconnected computers bring wholesale changes to the practice of medicine?

To be sure, not all technological possibilities have a major impact. Electric cars haven’t, nor has commercial nuclear power generation. But some have and others will.

“Something changed” when The Jazz Singer debuted on October 6, 1927. Movies didn’t used to have sound; now they did. With that single qualitative change, the lives of many stars and many directors of the silent movies were affected in a profound way. Some made the change, while some tried to adapt and failed. Others still clung to their old trade, simply adopting an attitude of denial in the face of a major environmental change and rationalizing their actions by questioning why anyone would want talking movies.

As late as 1931, Charlie Chaplin was still fighting the move to sound. In an interview that year, he proclaimed, “I give the talkies six months more.” Chaplin’s powerful audience appeal and craftsmanship were such that he was able to make successful silent movies throughout the 1930s. However, even Charlie Chaplin couldn’t hold out forever. Chaplin finally surrendered to spoken dialogue with The Great Dictator in 1940.

Others adjusted with great agility. Greta Garbo was a superstar of silent movies. With the advent of sound, in 1930 her studio introduced her to speaking roles in Anna Christie. Billboards proclaiming “Garbo speaks!” advertised the movie across the country. The movie was both a critical and a commercial success and Garbo went on to establish herself as a star of silent films who made a successful transition to talkies. What company would not be envious of getting through a strategic inflection point with such alacrity?

Yet is this industry going to be equally successful in navigating another strategic inflection point that’s caused by the advent of digital technology, by which actors can be replaced by lifelike-looking, live-sounding digital creations? Pixar’s movie Toy Story is an example of what could be done in this fashion. It’s the first feature-length result of a new technology. What will this technology be able to do three years from now, five years from now, ten years from now? I suspect this technology will bring with it another strategic inflection point. It never ends.

Technology transformed the worldwide shipping industry as dramatically and decisively as sound transformed the movie industry. In the span of a decade, a virtual instant in the history of shipping, the standardization of shipbuilding designs, the creation of refrigerated transport ships and, most importantly, the evolution of containerization—a technology that permitted the easy transfer of cargo on and off ships—introduced a “10X” change in the productivity of shipping, reversing an inexorably rising trend in costs. The situation was ripe for a technological breakthrough in the way ports handled cargo—and it came.

As with the movie industry, some ports made the change, others tried but couldn’t, and many resolutely fought this trend. Consequently, the new technologies led to a worldwide reordering of shipping ports. As of the time of this writing, Singapore, its skyline filled with the silhouettes of modern port equipment, has emerged as a major shipping center in Southeast Asia and Seattle has become one of the foremost ports for containerized cargo ships on the West Coast. Without the room to accommodate modern equipment, New York City, once a major magnet for shipping, has been steadily losing money. Ports that didn’t adopt the new technologies have become candidates for redevelopment into shopping malls, recreation areas and waterfront apartment complexes.

After each strategic inflection point, there are winners and there are losers. Whether a port won or lost clearly depended on how it responded to the “10X” force in technology that engulfed it.

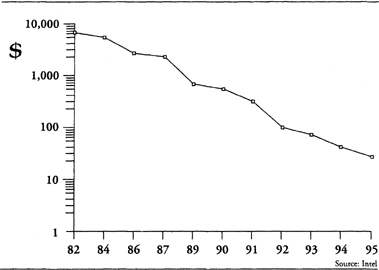

A fundamental rule in technology says that whatever can be done will be done. Consequently, once the PC brought a “10X” lower cost for a given performance, it was only a matter of time before its impact would spread through the entire computing world and transform it. This change didn’t happen from one day to the next. It came gradually, as the graph below indicates with price/performance trends.

Computer Economics: Cost Per MIPS

(a Measure of Computing Power)

Based on Fully Configured System Prices for Current Year

There were people in the industry who could surmise the appearance of this trend and who concluded that the price/performance characteristics of microprocessor-based PCs would win out in time. Some companies—NCR and Hewlett-Packard come to mind—modified their strategies to take advantage of the power of microprocessors. Other companies were in denial, much as Chaplin was with talkies.

Denial took different forms. In 1984 the then head of Digital Equipment Corporation, the largest mini-computer maker at the time, sounding a lot like Chaplin, described PCs as “cheap, shortlived and not-very-accurate machines.” This attitude was especially ironic when you consider Digital’s past. Digital broke into the world of computers, then dominated by mainframes, in the 1960s with simply designed and inexpensive mini-computers, and grew to become a very large company with that strategy. Yet when they were faced with a new technological change in their environment, Digital—once the revolutionary that attacked the mainframe world—now resisted this change along with the incumbents of the mainframe era.

In another example of denial, IBM’s management steadfastly blamed weakness in the worldwide economy as the cause of trouble at IBM in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and continued to do that year after year as PCs progressively transformed the face of computing.

Why would computer executives who had proven themselves to be brilliant and entrepreneurial managers throughout their careers have such a hard time facing the reality of a technologically driven strategic inflection point? Was it because they were sheltered from news from the periphery? Or was it because they had such enormous confidence that the skills that had helped them succeed in the past would help them succeed in the face of whatever the new technology should bring? Or was it because the objectively calculable consequence of facing up to the new world of computing, like the monumental cutbacks in staff that would be necessary, were so painful as to be inconceivable? It’s hard to know but the reaction is all too common. I think all these factors played a part, but the last one—the resistance to facing a painful new world—was the most important.

Perhaps the best analogy to Charlie Chaplin’s late conversion to the new medium is recent reports that Steve Chen, the former key designer of the immensely succesful Cray supercomputers, started a company of his own based on high-performance, industry-standard microprocessor chips. Chen’s previous company, which attempted to create the world’s fastest supercomputer, was one of the last holdouts of the old computing paradigm. But as Chen described his switch to a technological approach he once eschewed, he did so with a slight understatement: “I took a different approach this time.”

Customers drifting away from their former buying habits may provide the most subtle and insidious cause of a strategic inflection point—subtle and insidious because it takes place slowly. In an analysis of the history of business failures, Harvard Business School Professor Richard Tedlow came to the conclusion that businesses fail either because they leave their customers, i.e., they arbitrarily change a strategy that worked for them in the past (the obvious change), or because their customers leave them (the subtle one).

Think about it: Right now, a whole generation of young people in the United States has been brought up to take computers for granted. Pointing with a mouse is no more mysterious to them than hitting the “on” button on the television is to their parents. They feel utterly comfortable with using computers and are no more affected by their computer crashing than their parents are when their car stalls on a cold morning: They just shrug, mumble something and start up again. When they go to college, these young people get their homework assignments on the college’s networked computers, do their research on the Internet and arrange their weekend activities by e-mail.

Consumer companies that are counting on these young people as future customers need to be concerned with the pervasive change in how they get and generate information, transact their business and live their lives, or else those companies may lose their customers’ attention. Doesn’t this represent a demographic time bomb that is ticking away?

None of this is new. During the 1920s the market for automobiles changed slowly and subtly. Henry Ford’s slogan for the Model T—”It takes you there and brings you back”—epitomized the original attraction of the car as a mode of basic transportation. In 1921, more than half of all cars sold in the United States were Fords. But in a post-World War I world in which style and leisure had become important considerations in people’s lives, Alfred Sloan at General Motors saw a market for “a car for every purse and purpose.” Thanks to GM’s introduction of a varied product line and annual model changes, by the end of the decade General Motors had taken the lead in both profits and market share, and would continue to outperform Ford in profit for more than sixty years. General Motors saw the market changing and went with the change.

Sometimes a change in the customer base represents a subtle change of attitude, yet one so inexorable that it can have a “10X” force. In hindsight, the consumer reaction to the Pentium processor’s floating point flaw in 1994 represented such a change. The center of gravity of Intel’s customer base shifted over time from the computer manufacturers to the computer users. The “Intel Inside” program begun in 1991 established a mindset in computer users that they were, in fact, Intel’s customers, even though they didn’t actually buy anything from us. It was an attitude change, a change we actually stimulated, but one whose impact we at Intel did not fully comprehend.

Is the Pentium processor floating point incident a stand-alone incident, a bump in the road or, to use electronic parlance, “noise”? Or is it a “signal,” a fundamental change in whom we sell to and whom we service? I think it is the latter. The computer industry has largely become one that services consumers who use their own discretionary spending to purchase a product, and who apply the same expectations to those products that they have for other household goods. Intel has had to start adjusting to this new reality, and so have other players in this industry. The environment has changed for all of us. The good news is, we all have a much larger market. The bad news is, it is a much tougher market than we were accustomed to servicing.

The point is, what is a demographic time bomb for consumer companies represents good news for us in the computer business. Millions of young people grow up computer-sawy, taking our products for granted as a part of their lives. But (and there is always a but!) they’re going to be a lot more demanding of a product, a lot more discerning of weaknesses in it. Are all of us in this industry getting ready for this subtle shift? I’m not so sure.

Sometimes more than one of the six competitive forces changes in a big way. The combination of factors results in a strategic inflection point that can be even more dramatic than a strategic inflection point caused by just one force. The supercomputer industry, the part of the computer industry that supplies the most powerful of all computers, provides a good case in point. Supercomputers are used to study everything from nuclear energy to weather patterns. The industry’s approach was similar to the old vertical computer industry. Its customer base was heavily dependent on government spending, defense projects and other types of “Big Research.”

Both changed in approximately the same time frame. Technology moved to a microprocessor base and government spending dried up when the Cold War ended, increasing pressure on defense-spending reduction. The result is that a $1 billion industry that had been the pride and joy of U.S. technology and a mainstay of the defense posture of this country is suddenly in trouble. Nothing signifies this more than the fact that Cray Computer Corporation, a company founded by the icon of the supercomputer age, Seymour Cray, was unable to maintain operations due to lack of funds. It’s yet another example illustrating that the person who is the star of a previous era is often the last one to adapt to change, the last one to yield to the logic of a strategic inflection point and tends to fall harder than most.

Businesses often take their suppliers for granted. They are there to serve us and, if we don’t like what they do, we tend to think we can always replace them with someone who better fills our needs. But sometimes, whether because of a change in technology or a change in industry structure, suppliers can become very powerful—so powerful, in fact, that they can affect the way the rest of the industry does business.

Recently, the supplier base in the travel industry has attempted to flex its muscles. Here, the principal supplier is the airlines, which used to grant travel agents a 10 percent commission on every ticket sold. Even though travel-agent commissions were the airline industry’s third largest cost (after labor and fuel), airlines had avoided changing the commission rates because travel agents sell about 85 percent of all tickets and they did not want to antagonize them. However, rising prices and industry cutbacks finally forced the airlines to place a cap on commissions.

Can travel agencies continue as before in the face of a significant loss of income? Within days of the airlines’ decision, two of the country’s largest agencies instituted a policy of charging customers for low-cost purchases. Will such a charge stick? What should the travel agencies do if the caps on commissions remain a fact of life and if their customers won’t absorb any of their changes? One industry association predicted that 40 percent of all agencies might go out of business. It is possible that this single act by the suppliers can precipitate a strategic inflection point that might in time alter the entire travel industry.

Intel, in its capacity as a supplier of microprocessors, accelerated the morphing of the computer industry when we changed our practice of second sourcing.

Second sourcing, once common in our industry, refers to a practice in which a supplier, in order to make sure that his product is widely accepted, turns to his competitors and offers them technical know-how, so that they, too, can supply this product.

In theory, this unnatural competitive act works out as a win for all parties: the developer of the product benefits by a wider customer acceptance of the product as a result of a broader supplier base; the second-source supplier, who is a recipient of the technology, clearly benefits by getting valuable technology while giving little in return. And the customer for the product in question benefits by having a larger number of suppliers who will compete for his business.

In practice, however, things don’t often work out that well. When the product needs help in the marketplace, the second source usually is not yet producing, so the primary source and the customers don’t have the benefit of the extended supply. Once the product is fully in production and supply catches up with demand, the second source is in production too, so multiple companies now compete for the same business. This may please the customer but certainly hurts the wallet of the prime source. And so it goes.

By the mid-eighties, we found that the disadvantages of this practice outweighed its advantages for us. So we changed. Our resolve hardened by tough business conditions (more about this in the next chapter), we decided to demand tangible compensation for our technology.

Our competitors were reluctant to pay for technology that we used to give away practically for free. Consequently, in the transition to the next microprocessor generation, we ended up with no second source and became the only source of microprocessors to our customers. Eventually our competition stopped waiting for our largesse and developed similar products on their own, but this took a number of years.

The impact this relatively minor change had on the entire PC industry was enormous. A key commodity, the standard microprocessor on which most personal computers were built, became available only from its developer—us. This, in turn, had two consequences. First, our influence on our customers increased. From their standpoint, this might have appeared as a “10X” force. Second, since most PCs increasingly were built on microprocessors from one supplier, they became more alike. This, in turn, had an impact on software developers, who could now concentrate their efforts on developing software for fundamentally similar computers built by many manufacturers. The result of the morphing of the computer industry, i.e., the emergence of computers as a practically interchangeable commodity, has been greatly aided by the common microprocessor on which they were built.

Changes in technology affecting the business of your complementors, companies whose products you depend on, can also have a profound effect on your business. The personal computer industry and Intel have had a mutual dependence on personal computing software companies. Should major technological changes affect the software business, through the complementary relationship these changes might affect our business as well.

For example, there is a school of thought that suggests that software generated for the Internet will grow in importance and eventually prevail in personal computing. If this were to happen, it would indirectly affect our business too. I’ll examine this in more depth in Chapter 9.

Until now, we have followed the possible changes that can take place when one of the six forces affecting the competitive well-being of a business changes by a “10X” factor. That diagram illustrates the workings of a free market—unregulated by any external agency or government. But in real business life, such regulations—their appearance or disappearance—can bring about changes just as profound as any that we have discussed.

The history of the American drug industry provides a dramatic example of how the environment can change with the onset of regulation. At the start of the twentieth century, patent medicines made up of alcohol and narcotics were peddled freely without any labels to warn consumers of the dangerous and addictive nature of their contents. The uncontrolled proliferation of patent medicines finally triggered the government into the business of regulating what was put into the bottles, and led to the passage of a law requiring manufacturers of all medicines to label the ingredients of their elixirs. In 1906, the Food and Drugs Act was passed by Congress.

The drug industry changed overnight. The introduction of the labeling requirement exposed the fact that patent medicines were spiked with everything from alcohol to morphine to cannabis to cocaine, and forced their manufacturers to reformulate their products or take them off the shelves. The competitive landscape changed in the wake of the passage of the Food and Drugs Act. Now a company that wanted to be in the drug business needed to develop knowledge and skills that were substantially different from before. Some companies navigated through this strategic inflection point; many others disappeared.

Regulatory changes have been instrumental in changing the nature of other very large industries. Consider the American telecommunications industry.

Prior to 1968, the U.S. telecommunications industry was practically a nationwide monopoly. AT&T—”the telephone company”—designed and manufactured its own equipment, ranging from telephone handsets to switching systems, and provided all connections between phone calls, both local and long distance. Then, in 1968, the Federal Communications Commission ruled that the phone company could not require the use of its own equipment at the customer’s location.

This decision changed the landscape for telephone handsets and switching systems. It opened the business up to foreign equipment manufacturers, including the major Japanese telecommunications companies. The business that had been the domain of the slow-moving, well-oiled monopoly of the benign “Ma Bell” became rife with competition from the likes of Northern Telecom of Canada, NEC and Fujitsu from Japan, and Silicon Valley startups like ROLM. Telephone handsets, which the customer used to receive as part of the service from the old AT&T, now became commodities to be purchased at the corner electronics store. They were largely made at low labor cost in countries in Asia and they came in all sorts of shapes, sizes and functions, competing aggressively in price. And the familiar ringing of the telephone was supplanted by a cacophony of buzzes.

But all this was only a prelude to even bigger events.

In the early 1970s the U.S. Government, following a private antitrust suit by AT&T competitor MCI, brought suit, demanding the breakup of the Bell system and asking for the separation of long-distance services from local-access services. The story goes that after years of wrangling in the federal courts, a struggle which promised to go on for many more years, Charles Brown, then chairman of AT&T, one morning called his staff one at a time and told them that instead of putting the company through many years of litigation with an uncertain outcome, he would voluntarily go along with the breakup of the company. By 1984 this decision became the basis for what is known as the Modified Final Judgment, supervised by Federal Judge Harold Greene, that prescribed the way long-distance companies were to conduct business with the seven regional telephone companies. The telephone service monopoly crumbled, practically overnight.

I called on AT&T locations in those days to sell Intel microprocessors to their switching systems divisions. I still remember the profound state of bewilderment of AT&T managers. They had been in the same business for most of their professional lives and simply had no clue as to how things would go now that the customary financial, personal and social rules by which they had conducted themselves, division to division, manager to manager, were broken.

The impact of those events on the entire communications industry was equally dramatic. A competitive long-distance industry was created. Over the subsequent decade, AT&T lost 40 percent of the long-distance market to a number of competitors, some of whom, like MCI and Sprint, became multibillion-dollar companies themselves. A new set of independent companies operating regional telephone systems, often called the Baby Bells, were created. Each of these, with revenues in the $10 billion range, was left the task of connecting individuals and companies in their area to each other and to a competitive long-distance network. The Modified Final Judgment let them operate as monopolies in their own areas, subject to a variety of restrictions in terms of the businesses they might or might not participate in.

The Baby Bells themselves now face a similar upheaval, as changes in technology prompt further regulatory moves. The evolution of cellular telephony and a cable network that reaches 60 percent of U.S. houses provides alternative ways of connecting to the individual customers. Even as I write this, Congress labors to catch up with the impact of these changes in technology. No matter which way the telecommunications act will be rewritten, no matter how much the Charlie Chaplins and Seymour Crays of telephony fight the changes, they are coming. On the other side of this inflection point there will be a far more competitive business landscape for all aspects of the telecommunications business.

Of course, in retrospect it is easy to see that the creation of pharmaceutical regulations ninety years ago and the events that shaped the current telecommunications industry a decade ago clearly represented strategic inflection points for those industries. It is harder to decide whether the crosscurrents you are experiencing right now represent one.

Much of the world is embroiled in what I want to call the “mother of all regulatory changes,” privatization. Companies that have had a long history of operating as state-owned monopolies, from China to the former Soviet Union to the United Kingdom, at the stroke of a pen are being placed in a competitive environment. They have no experience of how to deal with competition. They never had to market to consumers; after all, why would a monopoly have to court customers?

AT&T, for example, had no experience dealing with competition, so they never had to market their products or services. They had all the customers that there were. Their management grew up in a regulatory environment where their core competencies revolved around their ability to work with the regulators; their work force was accustomed to a paternalistic work environment.

In the ten years of the free-for-all that followed the Modified Final Judgment, AT&T lost 40 percent of the long-distance market. However, they also mastered consumer marketing skills. Now AT&T advertises on television for new customers, makes a point of thanking you for using AT&T every time you connect with them and has even developed a distinctive sound to signal their presence—a sort of warm and fuzzy bong—all examples of world-class consumer marketing by a company where marketing used to be seen as a foreign art.

Deutsche Bundespost Telekom, Germany’s state-owned telecommunications company, is slated to be liberalized by the end of 1997. To steer the renamed Deutsche Telekom through the troubled waters, the company’s supervisory board recently appointed a forty-five-year-old consumer marketing manager from Sony to be its next CEO. This action suggests that the board understands that the future will be very, very different from the past.

When most companies of a previously regulated economy are suddenly thrust into a competitive environment, the changes multiply. Management now has to excel at marketing their services in the midst of a global cacophony of competing products, and every person on the labor force suddenly must compete for his or her job with employees of similar companies on the other side of the globe. This is the greatest strategic inflection point of all. When such fundamental changes hit a whole economy simultaneously, their impact is cataclysmic. They affect an entire country’s political system, its social norms and its way of life. This is what we see in the former Soviet Union and, in a more controlled fashion, in China.

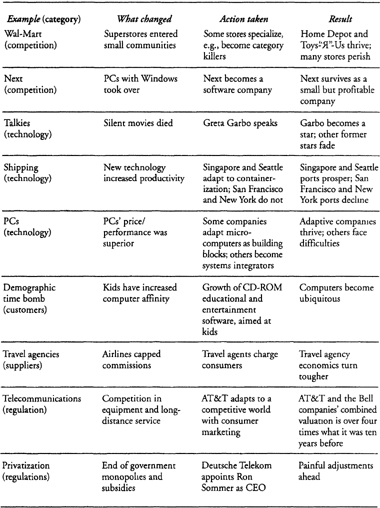

In this chapter I have tried to show that strategic inflection points are common; that they are not just a contemporary phenomenon, that they are not limited to the high-tech industry, nor are they something that only happens to the other guy. They are all different yet all share similar characteristics. The table provides a snapshot of what the examples in this chapter illustrate. As I scan it, I can’t help but be impressed by the variety and pervasiveness of strategic inflection points.

Note that everywhere there are winners and losers. And note also that, to a large extent, whether a company became a winner or a loser was related to its degree of adaptability. Strategic inflection points offer promises as well as threats. It is at such times of fundamental change that the cliché “adapt or die” takes on its true meaning.

Strategic Inflection Points:

Changes and Results