Managing, especially managing through a crisis, is an extremely personal affair.

Many years ago, in a management class I attended, the instructor played a scene from the World War II movie Twelve o’Clock High. In this movie, a new commander is called in to straighten out an unruly squadron of fliers who had become undisciplined to the point of self-destruction. On his way to take charge, the new commander stops his car, steps out and smokes a cigarette, while gazing off into the distance. Then he draws one last puff, throws the cigarette down, grinds it out with his heel and turns to his driver and says, “Okay, Sergeant, let’s go.” Our instructor played this scene over and over to illustrate a superbly enacted instance of building up the determination necessary to undertake the hard, unpleasant and treacherous task of leading a group of people through an excruciatingly tough set of changes—the moment when a leader decides to go forward, no matter what.

I always related to this scene and empathized with that officer. Little did I know when I watched that movie that I would have to go through something similar in a few years’ time. But beyond experiencing this crisis personally, the incident that I’m about to describe is how I learned with every fiber of my being what a strategic inflection point is about and what it takes to claw your way through one, inch by excruciating inch. It takes objectivity, the willingness to act on your convictions and the passion to mobilize people into supporting those convictions. This sounds like a tall order, and it is.

The story I’m going to tell you is about how Intel got out of the business it was founded on and how it refocused its efforts on and built a new identity in a totally different business—all in the midst of a crisis of mammoth proportions. I learned an enormous amount about managing through strategic inflection points as a result of this experience, and throughout the rest of this book, I will refer back to these events to illustrate what I learned. I’m afraid I have to drag you through some details. Bear with me. While the story is unique to Intel, the lessons, I believe, are universal.

Some history: Intel started in 1968. Every start-up has some kind of a core idea. Ours was simple. Semiconductor technology had grown capable of being able to put an ever larger number of transistors on a single silicon chip. We saw this as having some promising implications. An increasing transistor count readily translates into two enormous benefits for the customer: lower cost and higher performance. At the risk of some oversimplification, these come about as follows. Roughly speaking, it costs the same to produce a silicon chip with a larger number of transistors as a chip with a smaller number of transistors, so if we put more transistors on a chip, the cost per transistor would be lower. Not only that, smaller transistors are in closer proximity to each other and therefore handle electronic signals faster, which translates into higher performance in whatever finished gadget—calculator, VCR or computer—our chip should be placed into.

When we pondered the question of what we could do with this growing number of transistors, the answer seemed obvious: build chips that would perform the function of memory in computers. In other words, put more and more transistors on a chip and use them to increase the capacity of the computer’s memory. This approach would inevitably be more cost-effective than any other method, we reasoned, and the world would be ours.

We started modestly. Our first product was a 64-bit memory. No, this is not a typo. It could store 64 digits—numbers. Today people are working on chips that can store 64 million digits but this is today and that was then.

It turns out that, around the time Intel started, one of the then major computer companies had called for proposals to build exactly such a device. Six companies, all established in the business, had already bid on the project. We muscled our way in as the seventh bidder. We worked day and night to design the chip and, in parallel, develop the manufacturing process. We worked as if our life depended on it, as in a way it did. From that project emerged the first functional 64-bit memory. As the first to produce a working chip, we won the race. This was a big win for a start-up!

Next we poured our efforts into developing another chip, a 256-bit memory. Again, we worked day and night, and this was an even harder job. Thanks to a great deal of effort, we introduced our second product a short while after the first.

These products were marvels of 1969 technology and it seemed that every engineer in every organization of every computer maker as well as every semiconductor maker bought one of each to marvel over. Very few people, however, bought production volumes of either. Semiconductor memories were not much more than curiosity items at that time. So we continued to burn cash and went on to develop the next chip.

In the tradition of the industry, this chip would contain more transistors than the previous chip. We aimed at a memory chip that was four times more complex, containing 1,024 digits. This required taking some big technological gambles. But we plugged on, memory engineers, technologists, test engineers and others, a hard-working, if not always harmonious, team. As a result of the pressure we felt, we often spent as much time bickering with one another as working on the problems. But work went on. And this time we hit the jackpot.

This device became a big hit. Our new challenge became how to satisfy demand for it. To put this in perspective, we were a company composed of a handful of people with a new type of design and a fragile technology, housed in a little rented building, and we were trying to supply the seemingly insatiable appetite of large computer companies for memory chips. The incredibly tough task of development segued into the nightmare of producing a device that was held together with the silicon equivalent of baling wire and chewing gum. The name of this device was the 1103. To this day, when a digital watch shows that number, I and other survivors of that era still take note.

Through our struggle with the first two technological curiosities that didn’t sell and with the third one that sold but that we had such a hard time producing, Intel became a business and memory chips became an industry. As I think back, it’s clear to me that struggling with this tough technology and the accompanying manufacturing problems left an indelible imprint on Intel’s psyche. We became good at solving problems. We became highly focused on tangible results (our word for it is “output”). And from all the early bickering, we developed a style of ferociously arguing with one another while remaining friends (we call this “constructive confrontation”).

As the first mover, we had practically 100 percent share of the memory chip market segment. Then, in the early seventies, other companies entered and they won some business. They were small American companies, similar to us in size and makeup. They had names like Unisem, Advanced Memory Systems and Mostek. If you don’t recognize the names, it’s because these companies are long gone.

By the end of the seventies there were maybe a dozen players in the business, each of us competing to beat the others with the latest technological innovations. With each succeeding generation of memory chips, somebody, not necessarily the same company, got it right and it certainly wasn’t always us. A prominent financial analyst of the day used to report his observations of the memory business using boxing-match analogies: “Round Two goes to Intel, Round Three goes to Mostek, Round Four to Texas Instruments, we’re gearing up to fight Round Five” … and so on. We won our share. Even ten years into this business, we were one of the key participants. Intel still stood for memories; conversely, memories meant (usually) Intel.

Then, in the early eighties, the Japanese memory producers appeared on the scene. Actually, they had first shown up in the late seventies to fill the product shortages we had created when during a recession we pulled back our investments in production capacity. The Japanese were helpful then. They took the pressure off us. But in the early eighties they appeared in force—in overwhelming force.

Things started to feel different now. People who came back from visits to Japan told scary stories. At one big Japanese company, for instance, it was said that memory development activities occupied a whole huge building. Each floor housed designers working on a different memory generation, all at the same time: On one floor were the 16K people (where “K” stands for 1,024 bits), on the floor above were the 64K people and on the floor above that people were working on 256K-bit memories. There were even rumors that in secret projects people were working on a million-bit memory. All this was very scary from the point of view of what we still thought of as a little company in Santa Clara, California.

Then we were hit by the quality issue. Managers from Hewlett-Packard reported that quality levels of Japanese memories were consistently and substantially better than those produced by the American companies. In fact, the quality levels attributed to Japanese memories were beyond what we thought were possible. Our first reaction was denial. This had to be wrong. As people often do in this kind of situation, we vigorously attacked the ominous data. Only when we confirmed for ourselves that the claims were roughly right did we start to go to work on the quality of our product. But we were clearly behind.

As if this weren’t enough, the Japanese companies had capital advantages. They had (or were said to have) limitless access to funds—from the government? from the parent company through cross subsidies? or through the mysterious workings of the Japanese capital markets that provided nearly infinite low-cost capital to export-oriented producers? We didn’t know exactly how it all worked but the facts were incontrovertible: As the eighties went on, the Japanese producers were building large and modern factories, amassing a capacity base that was awesome from our perspective.

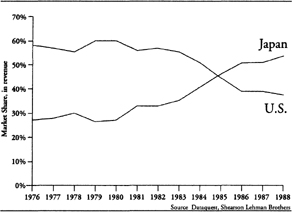

Riding the memory wave, the Japanese producers were taking over the world semiconductor market in front of our eyes. This penetration into the world markets didn’t happen overnight; as shown in the figure below, it took place over a decade.

Worldwide Semiconductor Market Share

We fought hard. We improved our quality and brought costs down but the Japanese producers fought back. Their principal weapon was the availability of high-quality product priced astonishingly low. In one instance, we got hold of a memo sent to the sales force of a large Japanese company. The key portion of the memo said, “Win with the 10% rule.… Find AMD [another American company] and Intel sockets.… Quote 10% below their price … If they requote, go 10% AGAIN.… Don’t quit till you WIN!”

This kind of thing was clearly discouraging but we fought on. We tried a lot of things. We tried to focus on a niche of the memory market segment, we tried to invent special-purpose memories called value-added designs, we introduced more advanced technologies and built memories with them. What we were desperately trying to do was to earn a premium for our product in the marketplace as we couldn’t match the Japanese downward pricing spiral. There was a saying at Intel at that time: “If we do well we may get ‘2X’ [twice] the price of Japanese memories, but what good does it do if ‘X’ gets smaller and smaller?”

Most importantly, we continued to spend heavily on R&D. After all, we were a company based on technology and we thought that every problem should have a technological solution. Our R&D was spread among three different technologies. Most of it was spent on memory chips. But at the same time a smaller team worked on technology for another device we had invented in 1970 or so: microprocessors. Microprocessors are the brains of the computer; they calculate while memory chips merely store. Microprocessors and memories are built with a similar silicon chip technology but microprocessors are designed differently than memories. And because they represented a slower-growing, smaller-volume market than memory chips, we didn’t stress their technological development as heavily.

The bulk of the memory chip development took place in a spanking new facility in Oregon. The microprocessor technology developers had to share a production facility—not even a new one at that—with the manufacturing folks at a remote site. Our priorities were formed by our identity; after all, memories were us.

While the situation on the memory front was tough, life was still good. In 1981, our then leading microprocessor was designed into the original IBM PC, and demand for it exploded far ahead of IBM’s expectation. IBM, in turn, looked to us to help them ramp up production of the IBM PC. So did all of IBM’s PC competitors. In 1983 and the early part of 1984 we had a heated-up market. Everything we made was in short supply. People were pleading with us for more parts and we were booking orders further and further out in time to guarantee a supply. We were scrambling to build more capacity, starting factory construction at different locations and hiring people to ramp up our production volumes.

Then in the fall of 1984 all of that changed. Business slowed down. It seemed that nobody wanted to buy chips anymore. Our order backlog evaporated like spring snow. After a period of disbelief, we started cutting back production. But after the long period of buildup, we couldn’t wind down fast enough to match the market slide. We were still building inventory even as our business headed south.

We had been losing money on memories for quite some time while trying to compete with the Japanese producers’ high-quality, low-priced, mass-produced parts. But because business had been so good, we just kept at it, looking for the magical answer that would give us a premium price. We persevered because we could afford to. However, once business slowed down across the board and our other products couldn’t take up the slack, the losses really started to hurt. The need for a different memory strategy, one that would stop the hemorrhage, was growing urgent.

We had meetings and more meetings, bickering and arguments, resulting in nothing but conflicting proposals. There were those who proposed what they called a “go for it” strategy: “Let’s build a gigantic factory dedicated to producing memories and nothing but memories, and let’s take on the Japanese.” Others proposed that we should get really clever and use an avant-garde technology, “go for it” but in a technological rather than a manufacturing sense and build something the Japanese producers couldn’t build. Others were still clinging to the idea that we could come up with special-purpose memories, an increasingly unlikely possibility as memories became a uniform worldwide commodity. Meanwhile, as the debates raged, we just went on losing more and more money. It was a grim and frustrating year. During that time we worked hard without a clear notion of how things were ever going to get better. We had lost our bearings. We were wandering in the valley of death.

I remember a time in the middle of 1985, after this aimless wandering had been going on for almost a year. I was in my office with Intel’s chairman and CEO, Gordon Moore, and we were discussing our quandary. Our mood was downbeat. I looked out the window at the Ferris wheel of the Great America amusement park revolving in the distance, then I turned back to Gordon and I asked, “If we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO, what do you think he would do?” Gordon answered without hesitation, “He would get us out of memories.” I stared at him, numb, then said, “Why shouldn’t you and I walk out the door, come back and do it ourselves?”

With that comment and with Gordon’s encouragement, we started on a very difficult journey. To be completely honest about it, as I started to discuss the possibility of getting out of the memory chip business with some of my associates, I had a hard time getting the words out of my mouth without equivocation. It was just too difficult a thing to say. Intel equaled memories in all of our minds. How could we give up our identity? How could we exist as a company that was not in the memory business? It was close to being inconceivable. Saying it to Gordon was one thing; talking to other people and implementing it in earnest was another.

Not only was I too tentative as I started discussing this course of action with colleagues, I was also talking to people who didn’t want to hear what I meant. As I got more and more frustrated that people didn’t want to hear what I couldn’t get myself to say, I grew more blunt and more specific in my language. The more blunt and specific I got, the more resistance, both overt and covert, I ran into.

So we debated endlessly. I remember at the end of a discussion asking one of our senior managers to write down what he understood our position to be on the subject; he was waffling as he struggled with the decision and I figured I could trap him with his own written memo. I failed. Months went by as we played these weird games.

In the course of one of my visits to a remote Intel location, I had dinner with the local senior managers, as I usually do. What they wanted to talk about was my attitude toward memories. I wasn’t ready to announce that we were getting out of the business yet because we were still in the early stages of wrestling with the implications of what getting out would mean—among them, what work would we have for this very group of people afterward? Yet I couldn’t get myself to pretend that nothing like this could ever happen. So I gave an ambivalent-to-negative answer, which this group immediately picked up on. One of them attacked me aggressively, asking, “Does it mean that you can conceive of Intel without being in the memory business?” I swallowed hard and said, “Yes, I guess I can.” All hell broke loose.

The company had a couple of beliefs that were as strong as religious dogmas. Both of them had to do with the importance of memories as the backbone of our manufacturing and sales activities. One was that memories were our “technology drivers.” What this phrase meant was that we always developed and refined our technologies on our memory products first because they were easier to test. Once the technology had been debugged on memories, we would apply it to microprocessors and other products. The other belief was the “full-product-line” dogma. According to this, our salesmen needed a full product line to do a good job in front of our customers; if they didn’t have a full product line, the customer would prefer to do business with our competitors who did.

Given the strength of these two beliefs, an open-minded, rational discussion about getting out of memories was practically impossible. What were we going to use for technology drivers? How were our salespeople going to do their jobs when they had an incomplete product family?

So it was on that night at this Intel dinner I described above. The rest of the evening was spent going in circles around these two issues, the management group and I getting increasingly frustrated with each other.

This was typical of discussions on the subject. In fact, the senior manager in charge of our memory business couldn’t get with the program even after months of discussions. Eventually he was offered a different job and accepted it, and I started with his replacement by spelling out exactly what I wanted him to do: Get us out of memories! By this time, having had months of frustrating discussions under my belt, I no longer had any difficulty making myself clear. Still, after the new person got acquainted with the situation, he took only half a step. He announced that we would do no further R&D on new products. However, he convinced me to finish what his group had in the works. In other words, he convinced me to continue to do R&D for a product that he and I both knew we had no plans to sell. I suppose that even though our minds were made up about where we were going our emotions were still holding both of us back from full commitment to the new direction.

I rationalized to myself that such a major change had to be accomplished in a number of smaller steps. But in a few months we came to the inevitable conclusion that this halfway decision was untenable and we finally worked up our determination and clearly decided—not just in the management ranks but throughout the whole organization—that we were getting out of the memory business, once and for all.

After all manner of gnashing of teeth, we told our sales force to notify our memory customers. This was one of the great bugaboos: How would our customers react? Would they stop doing business with us altogether now that we were letting them down? In fact, the reaction was, for all practical purposes, a big yawn. Our customers knew that we were not a very large factor in the market and they had half figured that we would get out; most of them had already made arrangements with other suppliers.

In fact, when we informed them of the decision, some of them reacted with the comment, “It sure took you a long time.” People who have no emotional stake in a decision can see what needs to be done sooner.

I believe this has a great deal to do with why there is such a high turnover in the ranks of CEOs today. Every day, it seems, leaders who have been with the company for most of their working lives announce their departure, usually as the company is struggling through a period that has the looks of a strategic inflection point. More often than not, these CEOs are replaced by someone from the outside.

I suspect that the people coming in are probably no better managers or leaders than the people they are replacing. They have only one advantage, but it may be crucial: unlike the person who has devoted his entire life to the company and therefore has a history of deep involvement in the sequence of events that led to the present mess, the new managers come unencumbered by such emotional involvement and therefore are capable of applying an impersonal logic to the situation. They can see things much more objectively than their predecessors did.

If existing management want to keep their jobs when the basics of the business are undergoing profound change, they must adopt an outsider’s intellectual objectivity. They must do what they need to do to get through the strategic inflection point unfettered by any emotional attachment to the past. That’s what Gordon and I had to do when we figuratively went out the door, stomped out our cigarettes and returned to do the job.

As we came back in that door, the main question we faced was this: if we are not doing memories, what should our future focus be? Microprocessors were the obvious candidate. We had now been supplying the key microprocessors for IBM-compatible PCs for nearly five years; we were the largest factor in the market. Furthermore, our next mainline microprocessor, the “386,” was ready to go into production. As I mentioned, its development was based on a technology developed in the corner of an old production plant. It would really have done much better in our most modern plant in Oregon but until now that place had been busy doing memory development. Getting out of the memory business gave us the opportunity to assign the group of developers in Oregon, who were arguably the best at Intel at this time, to the task of adapting their manufacturing process to build faster, cheaper, better 386s.

So I went up to Oregon. On the one hand, these developers were worried about their future. On the other hand, they were memory developers whose interest in and attachment to microprocessors was not very strong. I gathered them all in an auditorium and made a speech. The theme of the speech was, “Welcome to the mainstream.” I said that Intel’s mainstream was going to be microprocessors. By signing up to do microprocessor development, they would be bearing the flag for Intel’s mainline business.

It actually went a lot better than I had expected. These people, like our customers, had known what was inevitable before we in senior management faced up to it. There was a measure of relief that they no longer had to work on something that the company wasn’t fully committed to. This group, in fact, threw itself into microprocessor development and they have done a bang-up job ever since.

Elsewhere, however, the story was not so positive. These were very hard times and we were losing a lot of money. We had to lay off thousands of employees. We had no immediate use for the silicon fabrication plant where memories were made and had to shut it down. We also shut down assembly plants and testing plants that were involved with the production of memories. These also happened to be our oldest factories, situated in odd locations and too small for our business at this point anyway, so shutting them down gave us the opportunity to modernize our factory network. But that didn’t make it any less painful.

It was through the memory business crisis—and how we dealt with it—that I learned the meaning of a strategic inflection point. It’s a very personal experience. I learned how small and helpless you feel when facing a force that’s “10X” larger than what you are accustomed to. I experienced the confusion that engulfs you when something fundamental changes in the business, and I felt the frustration that comes when the things that worked for you in the past no longer do any good. I learned how desperately you want to run from dealing with even describing a new reality to close associates. And I experienced the exhilaration that comes from a set-jawed commitment to a new direction, unsure as that may be. Painful as it has all been, it turned me into a better manager. I learned some basic principles, too.

I learned that the word “point” in strategic inflection point is something of a misnomer. It’s not a point; it’s a long, torturous struggle.

In this case, the Japanese started beating us in the memory business in the early eighties. Intel’s performance started to slump when the entire industry weakened in mid-1984. The conversation with Gordon Moore that I described occurred in mid-1985. It took until mid-1986 to implement our exit from memories. Then it took another year before we returned to profitability. Going through the whole strategic inflection point took us a total of three years. And while today, ten years later, they now seem compressed to one short and intense period, at the time, those three years were long and arduous—and wasteful. While we were fighting the inevitable, trying out all sorts of clever marketing approaches, looking for a niche that couldn’t possibly exist in a commodity market, we were wasting time, getting deeper into red ink and ultimately forcing ourselves to take harsher actions to right things when we finally got around to taking action at all. While the realization of what we were facing was a flash of insight that took place in a single conversation, the work of implementing the consequences of that conversation went on for years.

I also learned that strategic inflection points, painful as they are for all participants, provide an opportunity to break out of a plateau and catapult to a higher level of achievement. Had we not changed our business strategy, we would have been relegated to an immensely tough economic existence and, for sure, a relatively insignificant role in our industry. By making a forceful move, things turned out far better for us.

What happened subsequently? The 386 became very, very successful, by far our most successful microprocessor to that point. Its success was greatly enhanced by the work of the former memory group in Oregon.

We were no longer a semiconductor memory company. As we started to search for a new identity for the corporation, we realized that all of our efforts now were devoted to the microprocessor business. We decided to characterize ourselves as a “microcomputer company.” This started first in our public statements, literature and advertising but over the years, as the 386 became a phenomenal success, it took hold of the hearts and minds of our management and most of our employees. Eventually the outside world started to look at us that way too.

By 1992, mostly owing to our success with microprocessors, we became the largest semiconductor company in the world, larger even than the Japanese companies that had beaten us in memories. And by now our identification with microprocessors is so strong that it’s difficult for us to get noticed for our nonmicroprocessor products.

Yet had we dithered longer, we could have missed our chance at all this. We might have vacillated between a heroic effort to hang on to our dwindling share of the memory business and an effort that might have been too weak to project us into the exploding microprocessor market. Had we stayed indecisive, we might have lost both.

One last lesson, and this is a key one: while Intel’s business changed and management was looking for clever memory strategies and arguing among themselves, trying to figure out how to fight an unwinnable war, men and women lower in the organization, unbeknownst to us, got us ready to execute the strategic turn that saved our necks and gave us a great future.

Over time, more and more of our production resources were directed to the emerging microprocessor business, not as a result of any specific strategic direction by senior management but as a result of daily decisions by middle managers: the production planners and the finance people who sat around the table at endless production allocation meetings. Bit by bit, they allocated more and more of our silicon wafer production capacities to those lines which were more profitable, like microprocessors, by taking production capacity away from the money-losing memory business. Simply by doing their daily work, these middle managers were adjusting Intel’s strategic posture. By the time we made the decision to exit the memory business, only one out of eight silicon fabrication plants was producing memories. The exit decision had less drastic consequences as a result of the actions of our middle managers.

This is not unusual. People in the trenches are usually in touch with impending changes early. Salespeople understand shifting customer demands before management does; financial analysts are the earliest to know when the fundamentals of a business change.

While management was kept from responding by beliefs that were shaped by our earlier successes, our production planners and financial analysts dealt with allocations and numbers in an objective world. For us senior managers, it took the crisis of an economic cycle and the sight of unrelenting red ink before we could summon up the gumption needed to execute a dramatic departure from our past.

Were we unusual? I don’t think so. I think Intel was a well-managed company with a strong corporate culture, outstanding employees and a good track record. After all, we weren’t quite seventeen years old, and in those seventeen years we had created several major business areas. We were good. But when we were caught up in a strategic inflection point, we almost missed it; we nearly became another Unisem, another Mostek, another Advanced Memory Systems.