When I think about what it’s like to get through a strategic inflection point, I’m reminded of a classic scene in old western movies in which a bedraggled group of riders is traveling through a hostile landscape. They don’t know exactly where they are going; they only know that they can’t turn back and must trust that they will eventually reach a place where things are better.

Taking an organization through a strategic inflection point is a march through unknown territory. The rules of business are unfamiliar or have not yet been formed. Consequently, you and your associates lack a mental map of the new environment, and even the shape of your desired goal is not completely clear.

Things are tense. Often in the course of traversing a strategic inflection point your people lose confidence in you and in each other, and what’s worse, you lose confidence in yourself. Members of management are likely to blame one another for the tough times the company is experiencing. Infighting ensues, arguments as to what direction to take bubble up and proliferate.

Then, at some point, you, the leader, begin to sense a vague outline of the new direction. By this time, however, your company is dispirited, demoralized or just plain tired. Getting this far took a lot of energy from you; you must now reach into whatever reservoir of energy you have left to motivate yourself and, most importantly, the people who depend on you so you can become healthy again.

I think of this hostile landscape through which you and your company must struggle—or else perish—as the valley of death. It is an inevitable part of every strategic inflection point. You can’t avoid it, nor can you make it less perilous, but you can do a better job of dealing with it.

To make it through the valley of death successfully, your first task is to form a mental image of what the company should look like when you get to the other side. This image not only needs to be clear enough for you to visualize but it also has to be crisp enough so you can communicate it simply to your tired, demoralized and confused staff. Will Intel be a broad-based semiconductor company, a memory company or a microprocessor company? Will Next be a computer company or a software company? What exactly is your bookstore going to be about—will it be a pleasant place to drink coffee and read or a place where you go to buy books at a discount?

You need to answer these questions in a single phrase that everybody can remember and, over time, can understand to mean exactly what you intended. In 1986, when we came up with the slogan “Intel, the microcomputer company,” that was exactly what we were trying to achieve. The phrase didn’t say anything about semiconductors, it didn’t say anything about memories. It was meant to project our mental image of the company as we would emerge from the valley of death that the 1985–86 memory debacle/strategic inflection point represented for us.

Management writers use the word “vision” for this. That’s too lofty for my taste. What you’re trying to do is capture the essence of the company and the focus of its business. You are trying to define what the company will be, yet that can only be done if you also undertake to define what the company will not be.

Doing this should actually be a little easier at this point because, as you’re coming out of a very bad period, you’re likely to have extremely strong feelings about what you don’t want to be. By 1986 we knew we did not want to be in the memory business any longer. We knew it with a passion that only comes after struggling with a business and finding that we were no better off for those struggles.

There are dangers in this approach: the danger of oversimplifying the identity of the company, of narrowing its strategic focus too much, so that some people will say, “But what about my part of the business … does this mean that we are no longer interested in that?” After all, Intel continued to do things other than microprocessors. We even continued to maintain a substantial business in a different type of semiconductor memories.

But the danger of oversimplification pales in comparison with the danger of catering to the desire of every manager to be included in the simple description of the refocused business, therefore making that description so lofty and so inclusive as to be meaningless.

Consider the following example that shows the value of a strong strategic focus. Lotus’s identity for its first ten years was as a supplier of personal computer software, specifically spreadsheets. Owing to some missteps of their own but, most importantly, because of a “10X” increase in the forces of competition (what the Japanese memory producers were to us, Microsoft’s presence in applications software was to them), Lotus’s core business weakened over time. But while this was happening, Lotus had developed a new generation of software, embodied in their product Notes, that promised to bring the same kind of productivity gains to groups that spreadsheets had brought to individuals. Even as Lotus was struggling with spreadsheets and its related software business, its management committed itself to group computing to the extent of deemphasizing their spreadsheet business. It continued to invest in developing Notes throughout these difficult years and it mounted a major marketing and development program that suffused all the corporate statements.

To be sure, the story is still evolving. But from the standpoint of giving the company an unequivocal future, Lotus’s management did exactly the right thing. It was Lotus’s strength in Notes that ultimately motivated IBM to purchase the company for $3.5 billion.

Now consider an opposite example—of a company floundering to define itself. Recently, I met with a senior manager of a company with whom we were trying to collaborate to ensure that their product and our product worked together. To make this deal click, they needed to make some clear decisions about which technologies they were devoted to and which they weren’t. I was dealing with a man at the second-highest level of his company, yet I found him torn and indecisive. On the one hand, he seemed convinced that we should work together; on the other hand, he seemed almost paralyzed when he needed to commit to the necessary actions to make this collaboration happen.

A couple of days later his boss, the chief executive officer, was quoted making statements about the company’s intentions that unequivocally supported the direction I thought my visitor was leaning toward. I tore the article out of the newspaper, waved it in the face of my associates and announced, “I think we are in business.” My euphoria lasted twenty-four hours. The next day’s newspaper brought a retraction, described as a “clarification.” It was all a big misunderstanding.

Now think for a moment of what it must be like to be a marketing or sales manager being buffeted by such ambiguities coming from your boss. Not only that, imagine what it would feel like to read about his direction du jour when it appears in the newspaper. How can you motivate yourself to continue to follow a leader when he appears to be going around in circles?

I can’t help but wonder why leaders are so often hesitant to lead. I guess it takes a lot of conviction and trusting your gut to get ahead of your peers, your staff and your employees while they are still squabbling about which path to take, and set an unhesitating, unequivocal course whose rightness or wrongness will not be known for years. Such a decision really tests the mettle of the leader. By contrast, it doesn’t take much self-confidence to downsize a company—after all, how can you go wrong by shuttering factories and laying people off if the benefits of such actions are going to show up in tomorrow’s bottom line and will be applauded by the financial community?

Getting through strategic inflection points represents a fundamental transformation of your company from what you were to what you will be. The reason such a transformation is so hard is that all parts of the company were shaped by what you had been in the past. If you and your staff got your experience managing a computer company, how can you even imagine managing a software company? If you got your experience managing a broad-based semiconductor company, how can you even imagine what a microcomputer company might be like? Not surprisingly, the transformation implicit in surviving a strategic inflection point involves changing members of management one way or another.

I remember a meeting of our executive staff in which we were discussing Intel’s new direction as a “microcomputer company.” Our chairman, Gordon Moore, said, “You know, if we’re really serious about this, half of our executive staff had better become software types in five years’ time.” The implication was that either the people in the room needed to change their areas of knowledge and expertise or the people themselves needed to be changed. I remember looking around the room, wondering who might remain and who might not. As it turned out, Gordon Moore was right. In our case, about half the management transformed themselves and were able to move in the new direction. Others ended up leaving the company.

Seeing, imagining and sensing the new shape of things is the first step. Be clear in this but be realistic also. Don’t compromise and don’t kid yourself. If you are describing a purpose that deep down you know you can’t achieve, you are dooming your chances of climbing out of the valley of death.

As Drucker suggests, the key activity that’s required in the course of transforming an organization is a wholesale shifting of resources from what was appropriate for the old idea of the business to what is appropriate for the new. Over the three years that the production planners at Intel gradually cut the allotment of wafer production for memories and moved it to microprocessors, they were shifting rare and valuable resources from an area of lower value to an area of higher value. But raw materials are not your only resource.

Your best people—their knowledge, skills and expertise—are an equally important resource. When we recently assigned a key manager from overseeing our next generation of microprocessors to a brand-new communications product line which is not likely to make us money for several years, we were shifting an extremely valuable resource. While he was very productive in his former area, there were others equally good to take his place there, while the new area badly needed the turbocharging his presence would give it.

A person’s time is an extremely valuable yet manifestly finite resource. When Intel was making its transformation from a “semiconductor company” to a “microcomputer company,” I realized that I needed to learn more about the software world. After all, how we would do our job depended on the plans, thoughts, desires and visions of the software industry. So I deliberately started to spend a significant amount of time getting acquainted with software people. I set out to visit heads of software companies. I called them up one at a time, made appointments, met with them and asked them to talk to me about their business—as it were, to teach me.

This entailed some personal risk. It required swallowing my pride and admitting how little I knew about their business. I had to walk into conversations with important people whom I had never met, not having a clue how they would respond. It also required a measure of diligence; as I sat talking with these people, I took copious notes, some of which I understood and some of which I didn’t. I then took the stuff that I didn’t understand back to our internal experts and asked them to explain what this individual might have meant by it. Basically, I went back to school. (I was aided by the fact that Intel is a schoolish company, where it’s perfectly respectable for a senior person with twenty years of experience to take some time, buckle down and learn a whole new set of skills.)

Admitting that you need to learn something new is always difficult. It is even harder if you are a senior manager who is accustomed to the automatic deference which people accord you owing to your position. But if you don’t fight it, that very deference may become a wall that isolates you from learning new things. It all takes self-discipline.

The discipline of redeployment is needed in spades when it comes to your personal time. When I started on this software study, I had to take the time I spent on it away from other things. In other words, I had to be the “production planner” of my own time and had to reallocate the way I spent time at work. This brought with it its own difficulties because people who were accustomed to seeing me periodically no longer saw me as often as they used to. They started asking questions like, “Does this mean you no longer care about what we do?” I placated them as best I could, I reassigned tasks among other managers and, after a while, people accepted this as well as many other changes as being part of Intel’s new direction. But it wasn’t easy for them or me.

The point is that redeploying resources sounds like such an innocuous term: it implies that you’re putting more attention and energy into something, which is wonderful, positive and encouraging. But the inevitable counterpart is that you’re subtracting from someplace else. You’re taking something away: production resources, managerial resources or your own time. A strategic transformation requires discipline and redeployment of all resources; without them, it turns out to be nothing more than an empty cliché.

One more word about your own time: if you’re in a leadership position, how you spend your time has enormous symbolic value. It will communicate what’s important or what isn’t far more powerfully than all the speeches you can give.

Strategic change doesn’t just start at the top. It starts with your calendar.

Assigning or reassigning resources in order to pursue a strategic goal is an example of what I call strategic action. I’m convinced that corporate strategy is formulated by a series of such actions, far more so than through conventional top-down strategic planning. In my experience, the latter always turns into sterile statements, rarely gaining traction in the real work of the corporation. Strategic actions, on the other hand, always have real impact.

What’s the difference? Strategic plans are statements of what we intend to do. Strategic actions are steps we have already taken or are taking which suggest our longer-term intent. Strategic plans sound like a political speech. Strategic actions are concrete steps. They vary: They can be the assignment of an up-and-coming player to a new area of responsibility; they can be the opening of sales offices in a portion of the world where we haven’t done business before; they can be a cutback in the development effort that deals with a long-pursued area of our business. All of these are real and suggest directional changes.

While strategic plans are abstract and are usually couched in language that has no concrete meaning except to the company’s management, strategic actions matter because they immediately affect people’s lives. They change people’s work, as was the case when we shifted capacity from memory production to microprocessor production and our sales force had a different product mix. They cause consternation and raise eyebrows, as did the transfer of the Intel manager from the tried-and-true microprocessor business to an ambiguous new area.

Strategic plans deal with events that are so far in the future that they have little relevance to what you actually have to do today. So they don’t command true attention.

Strategic actions, however, take place in the present. Consequently, they command immediate attention. Their power comes from this very aspect. Even if any one strategic action changes the trajectory on which the corporation moves by only a few degrees, if those actions are consistent with the image of what the company should look like when it gets to the other side of the inflection point, every one of them will reinforce every other. That’s why I think the most effective way to transform a company is through a series of incremental changes that are consistent with a clearly articulated end result.

Yet strategic inflection points are times that can also benefit from more drastic and higher-profile strategic actions. By higher profile, I mean that they are seen, heard and questioned by many people. Take the example I described earlier when the statement by the chief executive of the company we were trying to do business with was quoted in the newspaper. It caused a large number of raised eyebrows and scores of “Does this mean that …?” questions. It afforded a perfect opportunity to reinforce a new strategic direction on a broad scale. Unfortunately, the next day’s retraction laid waste to this opportunity.

But while it is good for strategic actions during an inflection point to raise eyebrows, they must also be timed just right. Strategic actions, especially those involving redeployment, are like the actions of runners in a relay race. Runners need to pass the baton at precisely the right moment; being even a little bit early or a little bit late will slow down the team.

The timing of the transfer of resources from the old to the new has to be done with this crucial balance in mind. If you move resources from the old business, the old task, the old product too early, you may leave a task only 80 percent finished. With a little bit more effort, you could have reaped the full benefit. On the other hand, if you hang on to the old business too long, the opportunity for grabbing a new business opportunity, to add momentum to a new product area, to get aligned with the new order of things, may be lost. There is a period in between that provides the best compromise, when you have invested enough in the old business that it has momentum to get you through the period of transition while you deploy your resources to the new target area. This timing dilemma is illustrated below.

Resource Shift Dilemma

| RESOURCE SHIFT IS PREMATURE: previous task is not completed |

TIMING IS RIGHT: momentum of existing strategy is still positive; new threat or opportunity has been verified |

RESOURCE SHIFT IS LATE: opportunity for transformation is lost; decline may be irreversible |

When is the time right? When the momentum of your existing strategy is still positive, your business is still growing, your customers and complementors still think highly of you yet there’s enough evidence of blips on your radar screen to warrant, at a minimum, exploring their significance. If your exploration confirms that they are real and are gaining, shift more resources on to them.

Your tendency will almost always be to wait too long. Yet the consequences of being early are less onerous than the consequences of being late. If you act too early, chances are the momentum of your previous business is still healthy. Therefore even if you’re wrong, you’re in a better position to course-correct. For instance, you can even pull back to their old jobs people whom you’ve reassigned to other areas. Since they come from those tasks, they can pick up the pieces again in no time and help out. But management’s tendency is to hang on to the old, so their strategic actions are more likely to happen later rather than earlier. The risk is that if you are late you may already be in an irreversible decline.

Simply put, in times of change, managers almost always know which direction they should go in, but usually act too late and do too little. Correct for this tendency: Advance the pace of your actions and increase their magnitude. You’ll find that you’re more likely to be close to right.

The best moment to act varies from company to company. Some companies recognize that their key strengths are rapid response and fast execution. Such companies may profitably wait for others to test the limits of technological possibilities or market acceptance and then commit to following, catching up and passing them.

I describe such a strategy as a “taillight” approach. When you drive in the fog, it is a lot easier to drive fast if you’re chasing the taillights of the car ahead of you. The danger with a “taillight” strategy is that, once you catch up and pass, you will find yourself without a set of taillights to follow—and without the confidence and competence in setting your own course in a new direction.

Being an early mover involves different risks. The biggest danger facing an early-mover company is that it may have a hard time distinguishing a signal from a noise and start to respond to an inflection point that isn’t one. Moreover, even if it is right in its response, it is likely to be ahead of its market and will run a greater risk of getting caught up in the dangers of the “first instantiation,” as described in Chapter 6.

But offsetting these dangers is the possibility of greater rewards: The early movers are the only companies that have the potential to affect the structure of the industry and to define how the game is played by others. Only by such a strategy can you hope to compete for the future and shape your destiny to your advantage.

In recent years, we at Intel decided that we have a tremendous opportunity to exploit the personal computer as a universal information appliance. This wasn’t always possible; the traditional PC was largely used as a replacement for data entry terminals capable of displaying numbers and text appropriate only for commercial transactions. However, over the last several years, technology has brought appealing visual capabilities to the PC, endowing it with colorful graphics, sound and video, while retaining its important traditional characteristic: interactivity.

But while we saw the possibility of exploiting these capabilities and envisioned the PC as being in the middle of the information and entertainment revolution that was taking place around us, much of the rest of the world thought that all of these developments would take place around the more familiar television set. So we threw ourselves completely behind the concept that the PC would be the center of all these developments (the battle cry was “The PC Is It!”) and launched an industry-wide campaign to proselytize our view. At the same time, we aligned all of our technical developments inside the company to make the PC an even more compelling choice for this task. We were—and still are—trying to shape our future at a time when this idea doesn’t have broad currency. We were—and are—trying to be early movers.

A question that often comes up at times of strategic transformation is, should you pursue a highly focused approach, betting everything on one strategic goal, or should you hedge? The question may come in the form of an employee asking me, “Andy, shouldn’t we be investing in areas other than microprocessors instead of putting all of our eggs in one basket?” or “Andy, shouldn’t we work on enhancing the television set in addition to betting on personal computers?” I tend to believe Mark Twain hit it on the head when he said, “Put all of your eggs in one basket and WATCH THAT BASKET.”

It takes every erg of energy in your organization to do a good job pursuing one strategic aim, especially in the face of aggressive and competent competition.

There are several reasons for this. First, it is very hard to lead an organization out of the valley of death without a clear and simple strategic direction. After all, getting there sapped the energy of your organization; it demoralized your employees and often set them against one another. Demoralized organizations are unlikely to be able to deal with multiple objectives in their actions. It will be hard enough to lead them out with a single one.

If competition is chasing you (and they always are—this is why “only the paranoid survive”), you only get out of the valley of death by outrunning the people who are after you. And you can only outrun them if you commit yourself to a particular direction and go as fast as you can. You could argue that, since they are chasing you, you should give yourself all sorts of alternative directions—in other words, hedge. I say, “No.” Hedging is expensive and dilutes commitment. Without exquisite focus, the resources and energy of the organization will be spread a mile wide—and they will be an inch deep.

Second, while you’re going through the valley of death, you may think you see the other side, but you can’t be sure whether it’s truly the other side or just a mirage. Yet you have to commit yourself to a certain course and a certain pace, otherwise you will run out of water and energy before long.

If you’re wrong, you will die. But most companies don’t die because they are wrong; most die because they don’t commit themselves. They fritter away their momentum and their valuable resources while attempting to make a decision. The greatest danger is in standing still.

When a company is meandering, its management staff is demoralized. When the management staff is demoralized, nothing works: Every employee feels paralyzed. This is exactly when you need to have a strong leader setting a direction. And it doesn’t even have to be the best direction—just a strong, clear one.

Organizations in the valley of death have a natural tendency to drift back into the morass of confusion. They are very sensitive to obscure or ambiguous signals from their management.

Heads of companies often inadvertently contribute to this confusion. Some time ago a business reporter told me of an encounter with the head of a major Japanese corporation. The reporter was working on a profile of the company. When he asked questions that tried to clarify the strategy of the corporation, the other man angrily retorted, “Why would I tell you our strategy? So I could help our competitors?” I think this man wouldn’t talk about his strategy not because he was afraid of helping his competitors but because he didn’t have one: this company’s public statements have always struck me as extraordinarily ambiguous.

Another way to fuel confusion is to give conflicting messages. At times of transition, pronouncements from the heads of organizations are painstakingly scrutinized and greatly amplified, especially by employees. Earlier I described an executive who retracted a statement about his company’s strategic direction that had already appeared in the newspapers. After that retraction, his credibility had to have been damaged. He will have to work that much harder to impart direction and have people believe it. In other words, screw up once and it will take a lot more work later to communicate the right message to correct your mistake.

The point is this: how can you hope to mobilize a large team of employees to pull together, accept new and different job assignments, work in an uncertain environment and work hard despite the uncertainty of their future, if the leader of the company can’t or won’t articulate the shape of the other side of the valley?

Clarity of direction, which includes describing what we are going after as well as describing what we will not be going after, is exceedingly important at the late stage of a strategic transformation. Much as in the middle of the strategic inflection process you needed to let chaos reign in order to explore your alternatives, to lead your organization out of the resulting ambiguity and to energize your staff toward a new direction, you must rein in chaos.

The time for listening to the Cassandras is over. The time for experimentation is also over. The time to issue marching orders—exquisitely clear marching orders—to the organization is here. And the time to commit the resources of the corporation as well as your own resources—your own time, visibility, speeches, statements in external forums (which are always given more credibility inside the company than what you say directly to your employees)—is upon you. Most of all, you must be a role model of the new strategy. That is the best way to prove that you are committed to it.

How do you role-model a strategy? By showing your interest in the elements that lead to the strategic direction, by getting involved in the details that are appropriate to the new direction and by withdrawing attention, energy and involvement from those things that don’t fit. Overcorrect your actions, recognizing that the symbolic nature of your actions will amplify their impact within the organization.

You can overcorrect by neglecting or overdelegating details in areas that, while still important, do not fit your immediate strategic needs. There’s a danger in deemphasizing some important things but that’s a risk you have to take. If, as a result of your overcorrection and neglect, some of the nuts and bolts of your daily work get dropped, you can always go back and pick them up later. What you can’t correct is failing to make the appropriate high-profile strategic shift: at the right moment.

At times like this, your calendar becomes your most important strategic tool. Most executives’ schedules are shaped by the inertia of prior actions. You are likely to accept appointments, attend meetings and schedule activities that are similar to what you had been doing in the past. Break the mold now. Resist the tacit temptation to accept invitations or make appointments because you have done so in the past. Ask yourself the questions, “Will going to this meeting teach me about the new technology or the new market that I think is very important now? Will it introduce me to people who can help me in the new direction? Will it send a message about the importance of the new direction?” If so, go to it. If not, resist it.

The point is this: you can’t hedge in a choice of direction and you can’t hedge in your commitment to it. If you do, your people will be confused and after a while they will throw up their hands in resignation. Not only will you lose direction, but you will continue to sap the energy of your organization as well.

A difficulty in role-modeling a new strategic action is that leaders of large organizations, by the nature of their jobs, are often distanced from direct contact with many managers and employees. You can’t talk to everybody; you can’t look all of them in the eye and argue your point. So you need to find a way to project your determination, will and vision over a distance, much as the forces of a strong magnet affect iron filings.

When you have to reach large numbers of people, you can’t possibly overcommunicate and overclarify. Give a lot of speeches to your employees, go to their workplaces, get them together and explain over and over what you’re trying to achieve. (Take particular care to answer questions of the “Does it mean that …” variety. Those are the ones that offer the best chance of bringing your message home.) Your new thoughts and new arguments will take awhile to sink in. But you will find that repetition sharpens your articulation of the new direction and makes it increasingly clear to your employees. So speak and answer questions as often as possible; while it may seem like you’re repeating yourself, in reality you will be reinforcing a strategic message.

Middle management has a special role to play here. More than anyone, middle management can help you project your message over a distance. By including them in your thinking and doing a particularly good job of enlisting them as sources of amplification of your new direction, you can multiply your presence many times. Take extra time with them because otherwise you risk losing their wholehearted commitment.

The best aspect of this type of exposure is that you will test whether you can pass the gauntlet of your employees’ questions, assuming you have the kind of corporate culture in which they feel comfortable questioning you. Your employees’ questions are usually shrewd, and in a free environment they can question you in a way that no one else can. If there is strategic illogic in your thinking, they will sniff it out and poke at it.

This is not fun. You may want to hide from exposing the holes in your strategic thinking—after all, having them on display in front of a group of your own employees would be embarrassing, wouldn’t it? Yet I think it would be far better to let your employees find them when there’s still time to make corrections than to allow the marketplace to find them later.

Technology can help you here. E-mail gives us a very powerful new way to reach large numbers of people. In most modern organizations, every computer is connected to a corporate network through which it can send messages to every other computer on that network. By spending minutes in front of his computer, a manager can leave his mark on the thoughts of dozens, hundreds or even thousands of people in his organization and do so with the immediacy that only the bounce of electronic communications can generate.

One caveat: if your message is clear, it will provoke questions and responses which will come back to you through the same medium. Answer them. You don’t have to make a lot of time for that; a response of two or three lines can communicate the essence of your position. This is a high-leverage activity; your message will reach not just the individual to whom you are sending it, but is likely to be sent on to other employees of the network, reverberating, as it were, from computer to computer. So consider this as the electronic equivalent of answering a question at an employee forum. Be crisp and to the point, and your response will help move the thinking of employees toward the desired direction.

I spend some two hours a day reading and responding to messages that come to me from all over the world. I don’t generally read them all in one chunk but I almost always make sure that I’m caught up before my day is done. I have found that I can project my thoughts, reactions, biases and preferences very effectively through this means.

Equally important is the opportunity that incoming e-mail gives me to be exposed to the thoughts, reactions, biases and preferences of large numbers of people. More Cassandras bring me news from the periphery this way than through any other means. I witness more arguments, I hear more business gossip, sometimes from people I have never met, than I ever did when I could walk the halls of the one building that housed all Intel employees. What used to be referred to as “managing by walking around” has to a large extent been supplanted by letting your fingers do the walking on your computer keyboard. Given that Intel has now spread all around the world and I couldn’t walk the halls of our sixty-odd buildings even if I spent full time at it, this has become doubly important.

A lot of times, management attempts to communicate a new strategic direction by the medium of closed-circuit television or prerecorded videotape. This may seem like a logical and easy thing to do but it won’t work. The interactive element, the give-and-take, the opportunity to ask the “Does it mean that …” type of question is lost in this one-way medium. If your employees don’t have an opportunity to test your thinking in live sessions or electronically, your message will seem like so much hot air.

Resist the temptation to do what’s easy here. Communicating strategic change in an interactive, exposed fashion is not easy. But it is absolutely necessary.

Gordon Moore’s comment that half our staff would need to become software types in five years’ time was a very valid insight and one that has an equivalent in every company that’s struggling with a “10X” force. Simply put, you can’t change a company without changing its management. I’m not saying they have to pack up their desks and be replaced. I’m saying that they themselves, every one of them, needs to change to be more in tune with the mandates of the new environment. They may need to go back to school, they may need a new assignment, they may need to spend some years in a foreign post. They need to adapt. If they can’t or won’t, however, they will need to be replaced with others who are more in tune with the new world the company is heading to.

In our case, we achieved the changes in our management along the lines Gordon suggested. To be sure, some managers left and were replaced by others from within Intel whose backgrounds were much closer to the new requirements. But most of us learned new tricks. For example, as I described, I invested a fair amount of time in learning about the strategies of the software companies in the personal computer industry and establishing relationships with their managers. Others undertook parallel transitions to new assignments. Some even took a step back to a lower-level assignment—a demotion—and, fortified by experiences from which they learned skills that were more appropriate to our new direction, later rose back again in the management ranks. We do this often enough that it is an accepted way for managers to learn the new skills they need as the company heads in a new direction.

Intel isn’t alone in exhibiting adaptive behavior. A company that has consistently been able to adapt to new directions over fifty years is Hewlett-Packard. I had the opportunity to see how they go about it. In recent years the management of Hewlett-Packard decided to base their future microprocessor needs on Intel’s microprocessor technology. The implication of that was that their computer business, which now uses a microprocessor that they designed themselves, would have to grow to rely on a microprocessor that would be available not just to them but to their competition.

This is a profound change for their business and it had to have been a very hard decision to reach. I witnessed some of the discussions in meetings we had with them, and catching even a glimpse of the process gave me a sense as to why Hewlett-Packard has such a spectacular record of navigating transformations. The discussions were rational, nonthreatening and slow but they steadily moved forward instead of meandering around in circles.

Sometimes management may see the need for a dramatically different new direction but not be able to bring the rest of the company along with them. I have seen a videotape of John Sculley, CEO of Apple Computer from 1983 to 1993, telling a Harvard Business School gathering that two of the biggest mistakes of his career were not adapting Apple’s software to Intel’s microprocessors and not modifying Apple’s then revolutionary laser printer so that it would work with PCs other than those made by Apple. I was stunned when I heard this. Listening to Sculley gave me the impression that he understood the implications of the horizontal industry structure. It appeared that he just wasn’t strong enough to overpower Apple’s inertia of success that existed because of its fifteen-year history as a fully vertical computer company.

Then there is the intriguing case of Wang Laboratories. Under the leadership of the founder, Dr. An Wang, the company had gone through a tremendous transformation, from being a producer of desktop calculators to becoming a pioneer in distributed word processing systems. Dr. Wang understood these technologies and had an extremely strong hold on his company. His vision was law and his vision was generally spot on. But by 1989, when the PC revolution became truly significant, Dr. Wang was very ill. Without his firm hand at the helm and without senior managers who could step in and define the company’s new identity in this time of change, the company lost its strategic direction. This time the company didn’t make it through the transformation and actually ended up in Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Why couldn’t Apple and Wang rein in chaos?

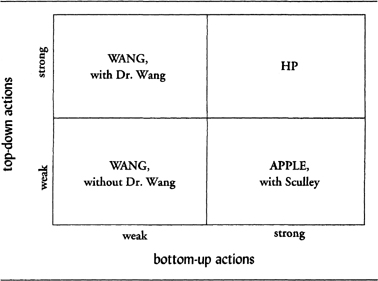

It seems that companies that successfully navigate through strategic inflection points have a good dialectic between bottom-up and top-down actions. Bottom-up actions come from the ranks of middle managers, who by the nature of their jobs are exposed to the first whiffs of the winds of change, who are located at the periphery of the action where change is first perceived (remember, snow melts at the periphery) and who therefore catch on early. But, by the nature of their work, they can only affect things locally: The production planners can affect wafer allocation but they can hardly affect marketing strategy. Their actions must meet halfway the actions generated by senior management. While those managers are isolated from the winds of change, once they commit themselves to a new direction, they can affect the strategy of the entire organization.

The best results seem to prevail when bottom-up and top-down actions are equally strong.

We can display this point in the following two-by-two matrix:

Dynamic Dialectic

The best quadrant to be in is the top right one—strong top-down and strong bottom-up actions roughly balancing.

If the actions are dynamic, if top management is able to alternately let chaos reign and then rein in chaos, such a dialectic can be very productive. When top management lets go a little, the bottom-up actions will drive toward chaos by experimenting, by pursuing different product strategies, by generally pulling the company in a multiplicity of directions. After such creative chaos reigns and a direction becomes clear, it is up to senior management to rein in chaos. A pendulum-like swing between the two types of actions is the best way to work your way through a strategic transformation.

This dynamic dialectic is a must. The wisdom to guide a company through the valley of death cannot as a practical matter reside solely in the heads of top management. If senior management is a product of the legacy of the company, its thinking is molded by the old rules. If they are from the outside, chances are they really don’t understand the evolving subtleties of the new direction. They must rely on middle management. Yet the burden of guidance also cannot rest solely on the judgment of middle management. They may have the detailed knowledge and the hands-on exposure but by necessity their experience is specialized and their outlook is local, not company-wide.

I learned this lesson the hard way. Intel before the crisis of the mid-1980s had a strategic planning system that was resolutely bottom-up. Middle managers were asked to prepare strategic plans for their areas, then at a detailed and lengthy session they presented their thoughts, strategies, requirements and plans to an assembled group of senior managers. These sessions were very one-way—middle managers did all the work leading to the presentations and they did most of the talking. We senior managers sat on the other side of the table and asked occasional questions, which worked to expose weaknesses of logic and inconsistency in the data. But our questions, which were largely nitpicky, didn’t even hint at strategic directions.

These sessions served their purpose as long as the overarching strategy of the company was simply to produce bigger and better semiconductor memories ahead of the competition. They filled in the details: what technology we needed to develop and how we would develop it, what products we would base on these technologies and so on.

But as we began to drift into the strategic inflection point that I described in Chapter 5, the woeful inability of this system to deal with big-time change became sorely evident. How could the middle managers who were responsible for memory products deal with the larger question of “Do we even have a chance in the memory business in the first place?” How could the head of the microprocessor organization raise the basic question, “Was it right for Intel to continue to put our best technology resources on the troubled memory business while starving the emerging microprocessor business?” Senior management needed to step in and make some very tough moves, and ultimately, under the duress of lots of red ink, we did. But we also realized then that there must be a better way to formulate strategy.

What we needed was a balanced interaction between the middle managers, with their deep knowledge but narrow focus, and senior management, whose larger perspective could set a context. The dialectic between these two would often result in searing intellectual debates. But through such debates the shape of the other side of the valley would become clear earlier, making a determined march in its direction more feasible.

An organization that has a culture that can deal with these two phases—debate (chaos reigns) and a determined march (chaos reined in)—is a powerful, adaptive organization.

Such an organization has two attributes:

1. It tolerates and even encourages debate. These debates are vigorous, devoted to exploring issues, indifferent to rank and include individuals of varied backgrounds.

2. It is capable of making and accepting clear decisions, with the entire organization then supporting the decision.

Organizations that have these characteristics are far more strategic-inflection-point-ready than others.

While the description of such a culture is seductively logical, it’s not a very easy environment in which to operate, particularly if you are a newcomer to it and are not familiar with the subtle transition in the swings of the pendulum. An example comes to mind. Some time ago we hired a very competent senior manager from outside Intel as part of the process of bringing computer expertise into our management ranks. He seemed to land on his feet, seemed to enjoy the give-and-take characteristic of our environment and diligently tried to follow the workings of the company as he understood them. Yet he missed the essence of what made it really work.

At one point he organized a committee and charged it to investigate an issue and come up with a recommendation. It turned out that this manager knew all along what he wanted to do, but instead of giving that direction to the committee, which he could have, he was hoping to engineer a bottom-up decision to the same effect. When the committee came up with the opposite recommendation, he felt cornered. At this late stage, he tried to dictate his solution to people who by now had spent months struggling with an issue and had firmed up their minds. It just couldn’t be done. Coming as it did at this late stage, his dictate seemed utterly arbitrary. The workings of our corporate culture rejected it, and the man had a very hard time understanding where he went wrong.

Many companies have gone through strategic inflection points. They are alive, competing, even winning. They have survived the challenges of their valleys of death and have emerged stronger than when they went in.

Hewlett-Packard grew to become a $30 billion company, largely owing to their success in computers. They are second only to IBM in that business.

Intel became the largest semiconductor producer in the world based on a microprocessor-centered strategy. And Intel coming out of the Pentium processor-flaw crisis is stronger than ever and more in tune with its customers.

Next is alive and contributing to the computer industry as a software company.

AT&T and the regional Bell companies thrive, compete and have a market valuation many times what AT&T had before the breakup.

The ports of Singapore and Seattle are thriving.

The Warner Brothers movie studio rode the sound wave to become a major media company.

The other side of the valley of death represents a new industry order that was hard to visualize before the transition. Management did not have a mental map of the new landscape before they encountered it. Getting through the strategic inflection point required enduring a period of confusion, experimentation and chaos, followed by a period of single-minded determination to pursue a new direction toward an initially nebulous goal. It required listening to Cassandras, deliberately fostering debates and constantly articulating the new direction, at first tentatively but more clearly with each repetition. It required casualties and personal transformation; it required accepting the fact that not all would survive and that those who did would not be the same as they had been before.

Beyond a doubt, going through the valley of death that a strategic inflection point represents is one of the most daunting tasks an organization has to endure. But when “10X” forces are upon us, the choice is taking on these changes or accepting an inevitable decline, which is no choice at all.