Netscape went public as I was working on this book. I knew of the company, and I thought that they had a lot of promise. But the way the stock skyrocketed on the first day it was available for public purchase and its continuing growth just blew me away. I could find no obvious rational explanation for this incredibly rapid stock appreciation. Something was going on, beyond merely a promising new company being discovered by a growing number of investors.

Netscape’s business premise was completely intertwined with the evolving Internet. And as the stocks of other Internet-based companies also soared in Netscape’s wake, it became clear that the investment community’s excitement had as much to do with the Internet as with Netscape.

The press was not far behind. An avalanche of long feature articles followed, generally creating a dramatized confrontation between software companies that based their activities on the Internet—typified by Netscape, or sometimes Sun—and the established order, as exemplified by Microsoft.

Something was going on, something was changing.…

For those of you who are not sure what the Internet is but perhaps were afraid to ask, let’s backtrack a bit. Simply put, the Internet is networks of computers connected to each other. If you have a personal computer in California and you’re connected to the Internet, you can exchange data with other computers connected to the Internet in California, in New York, in Germany or in Hong Kong, sort of like what’s shown in the sketch below.

The work leading to the Internet started in the late sixties with government-initiated—and -funded—connections between various big research computers. The idea was to provide a means of communication that could survive a nuclear explosion that might take down the country’s ordinary telephone infrastructure. Then other computers started joining in. The Internet kept growing and multiplying as people developed more university networks, corporate networks and government networks, and connected them to all the other previously linked networks. They were motivated by the premise that the more computers are connected to each other, the more useful it is to be connected. I like to think of the interlinked networks of all the computers on the Internet as forming a “connection co-op.”

An important element in establishing this “connection co-op” was defining a set of connection rules, so that any network that followed these rules could readily plug into the existing network. I imagine that the evolution of railroad networks in the last century must have followed a similar course. The myriad railroad companies needed to agree on common track gauges. Once they did that, every loop and spur could be connected to the rail networks that spanned the entire United States, and a boxcar could go from California to Kansas, crossing sections of track owned by different companies without a hitch. Similarly, today, a pile of data can originate in California, travel over a number of lines, cross the boundaries of many different networks and arrive at its destination, say, a computer in Kansas. In other words, the Internet provides a universal gauge for computer data.

The growth of this setup of interconnected computer networks has been under way for decades. At first the network served as the means for government and university researchers to communicate with one another. It grew at a moderate pace. Later, the Internet intersected another phenomenon: the mushrooming of personal computers connected to local area networks (LANs).

LANs were a phenomenon unrelated to the Internet. They were a consequence of the proliferation of PCs in corporations and other institutions. At first, PCs were used for individual tasks alone. Increasingly, however, they were connected to each other, first so that they could share an expensive printer, later so that they could exchange data, files and mail. Once large numbers of personal computers at each organization were interconnected through their own local area network, people got the idea that their LAN could be connected to the Internet. When that happened, that corporation’s network became part of the “connection co-op.” At this time, two phenomena—the growth of the original Internet and the growth of networked PCs—converged, and with the inclusion of corporate LANs, the Internet’s growth accelerated enormously.

Not only did the growth rate accelerate but the nature of participants in the Internet also changed. They originally consisted of university researchers sending their studies, papers and data to each other. But as millions of networked personal computers joined the “connection co-op,” the Internet became the means for every PC user to become connected to every other PC user.

How could such a complex network keep up with such unbridled growth? It could precisely because of the fact that is a “connection co-op.” As each corporation strengthens its own network, it contributes to the strength of the overall network. As in any good co-op, people acting in their own self-interest act in the interests of the whole.

Then there is also a major boost to the carrying capacity from the way the Internet operates. When it was first created, the idea was to provide many alternate routes by which to send data over long-distance telephone lines, so that if one route was blocked or didn’t work the system automatically found another one. This is done by large strings of data being broken down into smaller chunks, or packets, which are more easily absorbed into the stream of bits already flowing by. This approach expands the capacity of a network without additional investment. As a rough analogy, consider sending a group of passengers on a trip at the last minute. While it may be impossible for a large group to find a block of airline seats, individual passengers can generally get on board because there are usually a few random, empty places. The airline may even be willing to sell those tickets at a lower price because it doesn’t want to fly with empty seats. On the Internet, the packets of data are like passengers sitting in the otherwise empty seats of long-distance telephone networks. They fill the gaps between packets from other users. This method of transmission makes extremely efficient use of the existing telephone networks.

Two additional phenomena further accelerated the growth of the Internet. The first was the fact that personal computers were being improved and upgraded to become multimedia PCs, meaning that they were able to deal with colorful images, photos, sound and even video. The second was that a researcher at CERN (a European nuclear research organization) named Tim Berners-Lee developed a means of linking the data on one computer to the data on any other computer in a way that made it extremely simple for a computer user to perform such a feat. When you clicked on a highlighted key word, such as the name of a company, the connection would automatically be made throughout the entire Internet network, and the computer that contained information about that company would be opened up for your examination. The portion of the Internet that combines colorful graphics with Berners-Lee’s search method is the World Wide Web.

To a computer user, the fact that any PC on any person’s desk could become a window into millions of computers all over the world was like a miracle. And the fact that the material in those computers could be enhanced with colorful graphics, photographic images and even rudimentary sound and video made it a very seductive miracle.

To sum up, this miracle owed its existence to the confluence of four forces: the ongoing evolution of interconnected networks, the presence of large numbers of personal computers on local area networks that could be connected to the bigger network via a “universal gauge,” the spread of multimedia to personal computers and the Berners-Lee search method. Just as a mixture of chemicals consisting of just the right ingredients can undergo spontaneous combustion, this confluence brought about an explosion of public interest in the Internet. But is that explosion a flash in the pan or does it signal the start of a more lasting change?

It so happens that as I was writing this book Intel’s semiannual strategic gathering was coming up. My role at these occasions is to describe our business environment as I see it, and to call attention to significant changes. I felt that the Internet was the biggest change in our environment over the last year.

But that feeling was not enough. I needed to deal with the question, Could it be a “10X” force for Intel? If it is, what must we do?

After thinking about it quite a while, I felt that the phenomenon of connecting all the computers in the world has such a wide reach that it would affect a number of industries.

Because it is a communications technology, the Internet is, of course, likely to impact the telecommunications industry. Could it have a “10X” impact? Consider the cost of sending a certain amount of information over the telephone lines. The technology by which data packets are sent through the Internet uses the existing infrastructure so much more efficiently that it is rapidly delivering connection services that can be substantially less expensive than ordinary telephone connections. In other words, the data traffic on the Internet represents a more cost-effective, commodity-like method of connection than a traditional telephone call.

But beyond this it has further efficiencies as people translate an increasing portion of information previously sent by conventional telephony into data. It is a little bit like the way sending a fax compares to reading a document over the telephone; it is more cost-efficient because you can send a lot more information in a shorter period of time. All this suggests the potential to decrease telephone companies’ revenues.

But the Internet traffic also represents an extra business opportunity for telephone companies. It can be an opportunity to utilize the monumental investments they have made in building their connectivity infrastructure. This puts the long-distance carriers into a dilemma: Do they embrace the Internet or do they hide from it?

In other words, the Internet has pluses and minuses for the telecommunications industry. In the near term, growth of the use of the Internet may appear to be more of a threat. But in the long term, data rich in pictures, voice and video promise an even larger use of the Internet and therefore new business opportunities. If we put together a balance sheet of the impact of the Internet on the telecommunications industry, it would look something like the following table.

Pros and Cons of the Internet for the Telecommunications Industry

| Positives | Negatives |

| Additional data communications business | Conventional telephony can be replaced by data communications (it takes less traffic) |

| Utilizes investment made in infrastructure | Telecommunications could be commoditized |

| Pictures, voice and video mean lots of data (more traffic) | |

The Internet has potentially just as much impact on the software industry. It can provide a much, much more efficient way to distribute software. Think about it. Everything that flows on the Internet is a bunch of bits. And software is a bunch of bits. Software is distributed today by the manufacturers to people like you and me by putting those bits on a floppy disk or a CD-ROM, enclosing the disk or CD in a colorful cardboard box and stashing it on the shelf of retail stores much as if it were detergent or cereal.

However, the bits that make up a word processor or a computer game could just as readily be shipped by the manufacturer to your and my computers through the cost-effective method of the Internet. After all, if bits can flow freely from one computer to another, then someone can take pieces of software—even sizable pieces of software—and move them from one computer to another, or from one computer to a million others. No cardboard box and no shelf space are necessary. And no middleman. The whole sales process would clearly be more effective, not to mention how much easier it would be to upgrade or modify the software.

Look at this phenomenon from the standpoint of retailers, who have made a large business out of stocking and selling bits wrapped in those eye-catching boxes. Won’t the Internet have the same impact on these stores as the arrival of a Wal-Mart store would on a small-town retailer? This surely feels like a “10X” force.

Another phenomenon affecting the software business is that the Internet provides a brand-new foundation on which software can be designed. This foundation doesn’t care about the specific nature of any of the computers connected to the Internet—it works with all kinds of computers. If software—maybe lots of software—can be generated for this new target, won’t that siphon off business from Intel and from those computer manufacturers and software developers who have built their businesses around our products? Could it have a “10X” impact on them—and on us?

But again, this is not all. All the media companies are getting caught up in this swirl too. In the past several years practically every media organization—the Viacoms, the Time Warners—has founded “a new media” division for experimentation, much of which is now focused on the World Wide Web. Start-up companies are springing up on both coasts of the United States to service those companies who want to create their own Web site and to measure how many people look at their information as such. Even advertisers are joining in.

This could be an even bigger deal than what is happening to the telecommunications and the personal computing industries. By some estimates, worldwide spending on advertising is some $345 billion dollars. Right now, all of this money is spent on advertising in newspapers, magazines, radio and television. The money flows from advertisers like GM, Coca-Cola and Nike through the conventional media industry without any of it ending up in the pockets of the personal computing or telecommunications industries. That may be about to change.

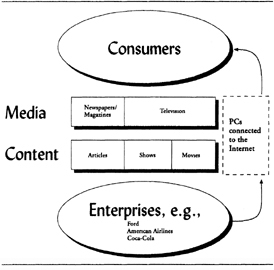

If I sketch a “before and after” map of the industry, it might look like the figures on the next page.

What this map suggests is that the Internet, or, to be precise, the World Wide Web, is another way for advertisers—the GMs, the Coca-Colas, the Nikes—to reach their consumers with their messages. To do that on a big scale, you have to “steal the eyeballs,” so to say, of the consumer audience from where they get those messages today (i.e., newspapers, magazines, radio and television) to displays on the World Wide Web. If this happens to any great extent, it would obviously be a big deal for both the old industries—the newspapers, magazines, radio and television networks—who would lose some of the funds, and also for the new industries—the connection providers, the people involved in generating the World Wide Web, the people who make the computers—who would gain some of those funds. What would be a boon to the latter would clearly be a loss to the former.

The Media Industry—Before the Internet

The Media Industry—After the Internet

But for this to happen in any big way, lots of eyeballs would have to be lured away from the traditional media. The information on the Internet would need to be made as appealing as the programming on traditional media today. There’s a lot of experimentation going on to make computer screens come alive: technology to make objects appear to be three-dimensional, to allow the viewer to move among them as if he were navigating in a room, to enrich the content with good-quality audio and video. All of these improvements could be brought to bear to jazz up the information found on the World Wide Web, so that it would match or even exceed the richness we are already accustomed to on the television screen. And the probability that PC production rates are likely to surpass combined black-and-white and color television production rates in the next year or two lends support to the plausibility that PCs connected by the Internet could, in fact, become a significant alternative to televisions.

Given the size of the media industry, the rewards to the new players would be enormous. Of course, so would be the loss to the traditional media industry—unless, that is, the market expands, reaches more people and therefore benefits all players. We may be witnessing the birth of a new media industry. If that is so, it surely represents a “10X” change!

As I began to prepare my assessment of Intel’s business environment for the upcoming meeting, I had lots of things to consider. Clearly, if interconnected computers represented the basis for a new media industry, that could have an enormous positive impact on our business. Much as improved personal productivity in offices drove the growth of our industry in the eighties, sharing data among working individuals continues to propel this growth in the nineties. Becoming a medium for the delivery of commercial messages could continue this growth into the next decade. For this to happen, content has to come to life, objects need to become three-dimensional and sound and video need to become ubiquitous. Processing the large number of bits that make these up requires higher and higher power microprocessors. This has wonderful promise for our business.

But (and there is always a but) if software developed for the Internet will run on anybody’s microprocessors, that would open our business to competition by a number of players who today are not really players because their chips don’t run the software that personal computer users predominantly use. Our product could be commoditized. And that’s not the only threat on the horizon.

A few industry figures have been going around touting the emergence of inexpensive “Internet appliances.” These simplified computers would rely on other larger centralized computers someplace on the Internet to store their data and to do much of their number crunching, and would just transmit to the computer users whatever software and data they needed, whenever they needed it. The argument goes that, this way, users would not have to know as much about computing as they do now because all of their tasks would be performed behind the scenes by the network of larger computers. Such an Internet appliance could be built around a simpler and less expensive microchip. Clearly, this would be detrimental to our business.

But there are a number of questions associated with this proposition. The most important is, Is such a computing device even technically feasible? It probably is, but it probably wouldn’t do much. Fundamentally, you can’t fool Mother Nature in computing, either. Inexpensive microprocessors are usually slow. A simple and cheap microprocessor would not do a wonderful job of creating content that is appealing enough to steal eyeballs. Surely one could make the sort of television sets that prevailed and functioned quite effectively twenty-five years ago for a lot less money than today’s TVs cost. But consumers don’t want yesterday’s capabilities in TVs—or in computers. And consumers may want lower prices but not at the risk of going back technically.

And there is an even more important issue involved. In 1995, some 60 million PCs were bought by consumers. What motivated these purchases? I think most of them were bought for two types of use: first, use that involves the individual user’s own data and own applications; and second, use that involves sending and sharing data to and with others, either within a corporate network or through the telephone system. The Internet fosters the emergence of a third class of use: applications and data that are stored at some other computer someplace, prepared and owned by unrelated individuals or organizations, that anyone can access through this pervasive, inexpensive set of connections, the “connection co-op.”

While this last category is amazing even as it is today, and probably has great promise going into the future, can it really effectively replace the first two classes of use? I don’t think so. I think a triad of categories of applications will prevail indefinitely. The beauty and allure of personal computers is the very flexibility with which they can deal with all three categories. A computing device that is useful for only one of these categories would not be attractive in comparison with a computing device that can deal with all three.

As I continued to work up my presentation, I realized it was time to draw up another balance sheet and take stock of all of these applications. I show this balance sheet on the next page.

Before we ask what this balance sheet adds up to, let’s ask a more basic question. Is the Internet that big a deal? Or is it an overhyped fad?

I think it is that big a deal. I think anything that can affect industries whose total revenue base is many hundreds of billions of dollars is a big deal.

Pros and Cons of the Internet for Intel

| Positives | Negatives |

| More applications | Microprocessors could be commoditized |

| Cheaper connectivity | More intelligence resides on centralized computer |

| Cheaper software distribution | Internet appliance might make do with a cheap microprocessor |

| Media business opens up; needs powerful microprocessors | |

Does it represent a strategic inflection point for Intel? Does it change any of the forces affecting our business, including our complementors, by a “10X” factor?

As I look at the above balance sheet, I don’t see that either our customers or our suppliers would be affected in a major way. What about our competition? Let’s apply the silver bullet test. Does the Internet bring on the scene players that would be more attractive targets for our silver bullet than the targets we have now? My gut says no. There will be new players on the scene to be sure, but they are just as likely to play the role of complementors as competitors. I certainly wouldn’t want to use a silver bullet to take out a complementor that might bring new capabilities to us.

Does my list of fellow travelers change? It does, because companies that used to be complementors to our competitors are now generating software that works as well on computers based on our microchips as on computers based on others. That makes them our complementors too. Also new companies are being created almost daily to take advantage of the opportunity provided by the Internet. Creative energy and funds are pouring in, much of which is going to bring new applications for our chips. So my fellow travelers are likely to grow in number, whereas I don’t see that we are about to lose any.

What about our people? Will they be out of it and not “get it?” I don’t think that’s very likely. A lot of our people have followed the evolution of the Internet from research to mass market both in their capacities as researchers and in their capacities as users of the mass-market version. Their presence ensures that we have the genetic mixture that represents this technology in our midst.

Let’s test for dissonance. Are we doing things that are different from what we are saying? We are busily involved in communicating Intel messages on the World Wide Web ourselves. We have ongoing contact with most of the key players in this emerging branch of our business. We even talk with the people who are advocating the development of the inexpensive Internet appliance without an Intel chip in it. I don’t see signs of strategic dissonance. But then again, as the CEO, I could very well be the last one to notice.

All this suggests that the Internet is not a strategic inflection point for Intel. But while the classic signs suggest it isn’t, the totality of all the changes is so overwhelming that deep down I think it is.

On balance, I think the promises of the Internet outweigh the threats. Still, we won’t harness the opportunity by simply letting things happen to us. Because this “we” specifically includes me, I have to ask, What do I do differently?

I decide to devote more than half of my environmental assessment to the Internet. While that’s an easy thing to decide, to fill my presentation with things I’m not embarrassed to say to my colleagues is harder. In other words, I have to study.

I read everything I can lay my hands on. I spend many hours searching out computers located on the World Wide Web and looking at their contents, reading the content of both competitors and oddball presences. I visit other companies, including those that at first blush might be regarded as the enemy because they are devoted to diminishing our business by putting an Internet appliance on the market as a substitute for PCs. I ask our own people to show me things we can do with PCs attached to the Internet.

Gradually, my picture gets clearer. I put my presentation together and finally give it to forty or so of our senior management team, some of whom know a whole lot more about my subject than I do and some of whom haven’t given any of it much thought. Comments on my presentation range from “This was the best strategic analysis you’ve ever done” to “Why the hell did you waste so much time on the Internet?” But I succeed with one thing: the center of gravity of our management discussion shifts measurably.

There seems to be a measure of embarrassment surrounding things to do with the Internet. People know a lot less than they let on. Being familiar with the Internet has become a cultural mandate that causes people to be embarrassed to ask basic questions, so my sense is that a lot of the familiarity that exists is extremely superficial. We set up a hands-on course for our senior managers and for our sales force, where they get to experience the current status of the World Wide Web first-hand. The hope is that this course will fill in the background bit by bit without confronting people with their ignorance point-blank.

I have to admit that my own knowledge is too superficial for my taste as well. But as my knowledge deepens, my conviction is growing that the triad of software coming from personal sources, from telephone and network sources and from the Internet will together be what will drive our industry in the years ahead. My conviction is also growing that the media and the advertising industries represent a growing opportunity for us.

We have a few problems in exploiting all this. We need to update our own genetic makeup, to be more in tune with the new environment. We have a whole slew of new fellow travelers that we need to get to know, to cultivate and learn to work with: software companies that we never had anything to do with in the past, telecommunications providers that are in the process of upgrading their networks, advertising and media companies that want to learn about our technology and advertisers who have paid no attention to the computing world until now but suddenly realize that they had better start.

Do we have the time, the attention and the discipline to play this more complex role? We may need to rethink our entire corporate organization structure and modify it to let us play this role with fewer internal complexities. Such a change would touch the lives of thousands of our employees. They would need to understand why we would tinker with what has worked well for us in the past.

Intel operates by following the direction set by three high-level corporate strategic objectives: the first has to do with our microprocessor business; the second with our communications business; the third with our operations and the execution of our plans. We add a fourth objective, encapsulating all the things that are necessary to mobilize our efforts in connection with the Internet. This is preceded by a lot of argument; some think we might just as well fold all the Internet-related things we need to do under the other three objectives. I feel otherwise. Packaging Internet activities separately and elevating them on a par with our other three objectives is a way to communicate their significance to the entire company.

Except for one last thing. What if the people who believe in the cheap Internet appliance turn out to be right?

It is likely that the Internet appliance is a case of turning the clock backward, given that the trend over the last twenty to thirty years has consisted of pulling down intelligence from big computers to little ones. I don’t believe that the Internet is about to reverse this trend. But then again, my genes were formed by those same twenty or thirty years. And I’m likely to be the last one to know.

So I think there is one more step for Intel to take to prepare ourselves for the future. And I think we should take it now while our market momentum is stronger than ever. I think we should put together a group to build the best inexpensive Internet appliance that can be built, around an Intel microchip. Let this group try to derail our strategies themselves. Let them be our own Cassandras. Let them be the first to tell us whether this can be done and whether what I now think is noise is, in fact, a strong signal that, once again, something has changed.