When I ask people why old places are important, a frequent answer is that old places provide people with a sense of continuity. But this idea of a sense of continuity, which so many people obviously feel, is not often explained. What does this sense of continuity mean, how does it tie to old places, and why is it good for people?

Based on my conversations and the research I’ve done at the American Academy in Rome, the idea of continuity is that, in a world that is constantly changing, old places provide people with a sense of being part of a continuum, which is necessary for them to be psychologically and emotionally healthy. This is an idea that people have long recognized as an underlying value of historic preservation, though it is not often explained. In the influential 1966 book With Heritage So Rich, the idea of continuity is captured in the phrase “sense of orientation,” the idea that preservation gives “a sense of orientation to our society, using structures and objects of the past to establish values of time and place.”1 Juhani Pallasmaa, the internationally known architect and architectural theorist, was a resident at the American Academy during my time there, and I’ve been privileged to talk with him about old places. Juhani puts it this way in an essay he wrote: “we have a mental need to experience that we are rooted in the continuity of time. We do not only inhabit space, we also dwell in time.” He continues: “Buildings and cities are museums of time. They emancipate us from the hurried time of the present and help us to experience the slow, healing time of the past. Architecture enables us to see and understand the slow processes of history and to participate in time cycles that surpass the scope of an individual life.”2

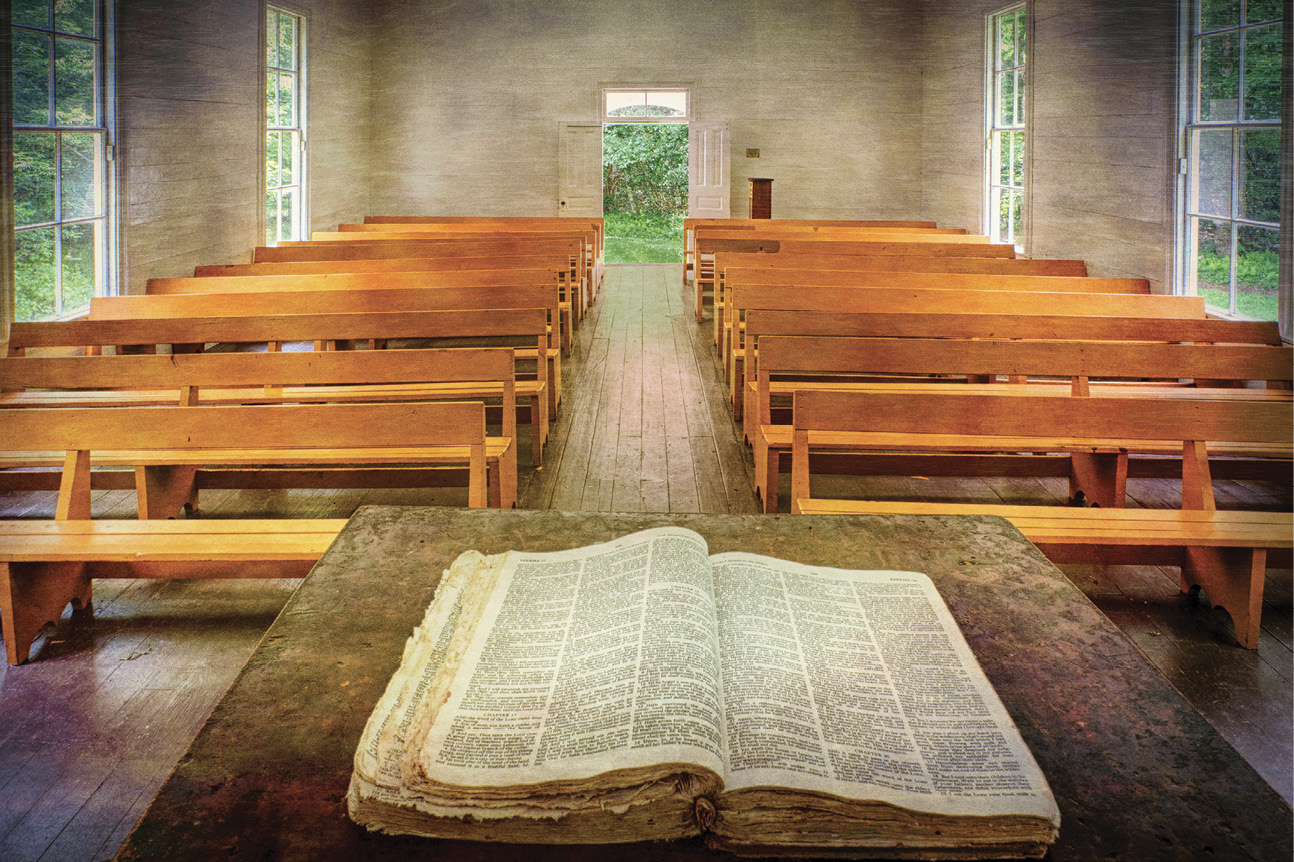

The interior of Palmer Chapel

Jeffrey Stoner Photography

Palmer Chapel, in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where generations of former residents return for an annual reunion, providing descendants with a sense of continuity between the past and the present

Jeff Clark/Internet Brothers

We see and hear this idea in the way people talk about the places they care about—in blogs, public hearings, newspaper articles, and anywhere people talk about threats to places they love. Discussing the potential loss of his one-hundred-year-old elementary school, for example, a resident says, “It’s been a part of my life as long as I can remember. . . . My great-grandmother graduated in 1917. . . . It’s the heart of the community.”

People share stories of the experiences that they, their parents, and other people have had at theaters, restaurants, parks, and houses—as well as events that happened long before their parents were alive. They not only feel the need to be part of a time line of history, both personal and beyond themselves, but their connection to these old places makes them aware that they are part of the continuum, connected to people of the past, the present, and, hopefully, the future.

Caldwell Station School, in Huntersville, North Carolina, where earlier generations of my family attended school

Stewart Gray

Environmental psychologists have explored many aspects of peoples’ attachment to place, including the idea of continuity. Maria Lewicka, in her review of studies on “place attachment,” says, “the majority of authors agree that development of emotional bonds with places is a prerequisite of psychological balance and good adjustment and that it helps to overcome identity crises and gives people the sense of stability they need in the everchanging world.”

Although studies relating specifically to old places are limited, Lewicka summarizes the studies this way: “Research in environmental aesthetics shows that people generally prefer historical places to modern architecture. Historical sites create a sense of continuity with the past, embody the group traditions, and facilitate place attachment.”

Lewicka’s summary of one study captures a key idea: “The important part . . . is the emphasis placed on the link between sense of place, developed through rootedness in place, and individual self-continuity. Rootedness, that is, the person-place bond, is considered a prerequisite of an ability to integrate various life experiences into a coherent life story, and thus it enables smooth transition from one identity stage to another in the life course.”3

Life story. This phrase captures the way people create a narrative out of their lives and make their lives meaningful and coherent. Old places help people to create meaningful life stories. This may sound a bit touchy-feely for our American sense of practicality and hard-nosed realism. But the point is that people need this sense of continuity, this capacity to develop coherent life stories, in order to be psychologically healthy.

We can see the importance of continuity in the places where continuity has been intentionally or unintentionally broken. People who have been forcibly removed from their homes, such as those who lived on the land that became Great Smoky Mountains National Park and were removed in the 1930s, described themselves as heartbroken by the forced removal. These former residents continue to visit the sites of their former homes—the remains of an old chimney, the foundation of an apple cellar, and the family graveyard—and to participate in homecomings, such as at the one at an old church named Palmer Chapel. Although they had been forcibly removed, the attachment to the place continued and has continued through later generations who never lived on the land but feel a sense of connection to the place.4

On a trip to Puglia, the fellows of the American Academy visited a World Heritage site, Matera, where the residents had been removed from their community during the mid-twentieth century. Our guide at one of the churches, a descendant of one of the families removed from the site, said that her grandmother hated moving and felt that the community never recovered from the forced removal. Studies have shown that the loss of the sense of continuity from uncontrollable change in the physical environment may even cause a grief reaction.5 Put simply, people need the continuity of old places.

Residents of Matera, Italy, were displaced for supposedly better housing but many say their community was never the same

Tom Mayes/National Trust for Historic Preservation

Continuity is not, however, only about the past, but also about the present and the future. That’s what continuity means—bringing the relevance of the past to give meaning to the present and the future. Paul Goldberger, the architectural critic, says about preservation,

Perhaps the most important thing to say about preservation when it is really working as it should is that it uses the past not to make us nostalgic, but to make us feel that we live in a better present, a present that has a broad reach and a great, sweeping arc, and that is not narrowly defined, but broadly defined by its connections to other eras, and its ability to embrace them in a larger, cumulative whole. Successful preservation makes time a continuum, not a series of disjointed, disconnected eras.6

Old places help people place themselves in that “great, sweeping arc” of time. The continued presence of old places—of the schools and playgrounds, parks and public squares, churches and houses and farms and fields that people value—contributes to people’s sense of being on a continuum with the past. That awareness gives meaning to the present and enhances the human capacity to envision the future. All of this contributes to people’s sense of well-being—to their psychological health.

Schools, such as Mt. Zion Rosenwald School in Mars Bluff, South Carolina, provide continuity between generations

Jason Clement/National Trust for Historic Preservation

Notes

1. Special Committee on Historic Preservation United States Conference of Mayors, With Heritage So Rich (Washington, DC: Preservation Books, 1999).

2. Juhani Pallasmaa, Encounters 1: Architectural Essays, ed. Peter MacKeith (Helsinki, Finland: Rakennustieto Oy Publishing, 2012), 309, 312.

3. Maria Lewicka, “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (2011): 211, 225 and “Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28 (2008): 211.

4. Michael Ann Williams, “Vernacular Architecture and the Park Removals: Traditionalization As Justification and Resistance,” TDSR 13, no. 1 (2001): 38.

5. Clare L. Twigger-Ross and David L. Uzzell, “Place and Identity Processes,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 16 (1996): 205–20.

6. Paul Goldberger, “Preservation Is Not Just about the Past,” speech, Salt Lake City, April 26, 2007.