Sharecroppers

I haven’t encountered too many pests or diseases during the winter. Slugs, mice, deer and rot are the main exceptions. But for the slow plants, ones that have to grow all summer to produce in the winter, there are indeed some formidable sharecroppers.

When dealing with any pest, I think it’s useful to take the time to understand the organism, its life cycle and its place in the local ecosystem. If you just run for the metaldehyde or the rotenone, you risk breeding resistant pests. Even worse, you never come to understand why you have this pest and if you can change your gardening habits to reduce its predation to an insignificant level.

One way of dealing with pests in a coordinated manner is through a set of procedures referred to as integrated pest management (IPM). What follows is a short outline of this method; for a longer discussion, read Helga Olkowski’s Gardener’s Guide to Common-Sense Pest Control (in print and online).

The first step in IPM is to systematically check out what is happening. What sort of damage is occurring and on which plants? Is it happening at night or in the day? Can you see the culprits or just their effect? (Perhaps a neighbor, your local extension agent or a Master Gardener can aid in identifying the organisms.) Will your yield be decreased? How much? This observation is called monitoring.

Once you have zeroed in on the pest organism, look at your yard and garden and figure out where the pest is hiding and if any of your gardening habits — or your ornamental vegetation — encourage or discourage the pest. Neatness and cleanliness are often next to pestlessness. Steps you take to change any of these factors to discourage the pest are habitat manipulation.

Sometimes when you plant a crop or how you take care of it will increase or decrease the damage. So changes in your gardening patterns — cultural controls — are a possibility. An example is waiting to transplant sensitive brassicas until most of the cabbage flies have stopped laying eggs.

Encouraging pest predators — biological controls — is helpful, too, though this is often difficult and expensive for home gardeners. In the maritime Northwest, we have many imported pests whose original habitats and predators were left behind. There may be useful local predators, though, and you can spend some time observing them. Birds and syrphid flies belong in this category. Importing predators is often useless, as they often migrate out of your garden. But you should learn to recognize your local ones. With reading and observation, you can learn to create habitats for the native predators you want to have around. See Appendix D for some useful titles.

You can also try barriers to keep the pest organism from getting to the crop. What method you use depends upon whether it flies, crawls, burrows or slimes. Setting traps is often effective.

Finally, there is the use of poisons, whether organic botanicals, such as rotenone, pyrethrum and derris, or the numerous and usually (though not always) more toxic chemical ones.

The IPM method takes a little extra time and attention on your part. It is not an instant solution. But then, instant solutions often have side effects which are nasty and long lasting. Better to observe carefully and continually, gather information, generate solutions and implement them thoughtfully — and only to the extent necessary.

I should add here that there are people who believe that pests do not attack healthy plants. They say that if the soil is in good tilth or balance, garden conditions are right and the gardener is not guilty of mismanagement, a clean, productive garden will result with few, if any, problems. I myself think that’s a complex set of ifs.

Certainly healthy, living soil and healthy plants are the best defense against disease and perhaps even predation, but often as not one inherits a garden site that is way out of balance. And we have little control over the practices of our neighbors, let alone those in adjacent sections of the county or city. Further, it takes some time and a lot of work to develop garden patterns that work well in a given site. So don’t despair or feel guilty or inadequate if you have some problems in your garden.

The nomenclature I use in the following descriptions follows Whitney Cranshaw, Garden Insects of North America the Ultimate Guide to Back Yard Bugs. This book has excellent photos and a good section on management principles for selected garden pests.

Cabbage Aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae)

Cabbage aphids are gray, mealy-looking critters that overwinter in colonies on the underside of leaves of mature brassica plants. In May, right after you’ve set out your transplants, the mature ones fly around looking for hosts. If they land on the young brassicas, they crawl down into the center of the plants and start feeding and hatching new aphids. This causes the leaves to warp and curl around them so they are hard to eradicate. If not stopped, they can permanently dwarf the plants.

Cabbage aphids are parasitized by tiny braconid wasps, whose offspring feed within the bodies of the young, turning them into little golden mummies. If you see a high proportion of mummies to feeding aphids, you can assume that control is under way. Then you need only give the seedlings or plants a boost with seaweed or manure teas or a mulch of aged manure. Other helpful predators of aphids are yellow jackets, lacewing larvae, lady beetles and their larvae and syrphid fly larvae. As the adults of the last of these prefer to feed on flowers of the Umbelliferae, or carrot family, I make sure to let some umbels, such as parsley, dill and coriander, go to flower for them. Flowers of the Composite family (asters, goldenrod) are also supportive in the end of the summer.

If you regularly overwinter kale, Purple Sprouting broccoli, and hardy cauliflowers, the chances are strong that the plants are sheltering overwintering colonies of mature aphids or their eggs. You should either clear out these plants by the middle of May or spray them with a solution of Safer’s Insecticidal Soap, which has worked well for me. Safer’s Insecticidal Soap is registered as an insecticide and is available in garden centers and greenhouse supply stores. Basic H, liquid Joy, liquid Ivory and vegetable soaps that are often found in co-ops and health food stores are not registered; however, they do work. Agencies just aren’t allowed by law to recommend them. Most detergents are phytotoxic (bad for plants), and it’s best not to use anything with fragrances in them.

If your young plants become infested with aphids during the summer months, you can wipe them off with your fingers and just spray a little soap solution down into the center right around the growing tip. Protecting young cabbage plants by this method takes some persistence, but it’s worth it. Some hot, dry summers encourage aphids and you have to guard even the older plants. Leaves and stalks damaged by aphids are susceptible to mold in later rainy weather.

Cabbage Looper (Trichoplusia ni) and Imported Cabbageworms (Pieris rapae)

The larvae of a white butterfly, the imported cabbageworm; and of a brownish moth, the cabbage looper, both eat holes in the leaves of cabbages and sometimes broccoli. They are frequently a problem in western Washington.

There are at least two and sometimes three generations of butterflies each year. The first generation, in the spring, is not as intense as the late summer ones. Though the moth goes through several generations, I have observed its larvae only in the late summer. Both kinds of larvae can be picked off by hand, although because they hide down in the inner leaves they are hard to find. Holes in the leaves and little mounds of green droppings are signs that they are about. If you have more than a few plants and not much time, Thuricide or other Bacillus thuringiensis preparations are useful. Bt is a bacterium largely specific to butterfly and moth larvae; they eat it, and it paralyzes them.

As with most pests, it’s best to treat for them when you can see that the problem is going to be serious. A few stray caterpillars won’t hurt a well-developed plant much, but they can ravage a young one. If they are bad in the late summer you can have many stunted winter cabbages.

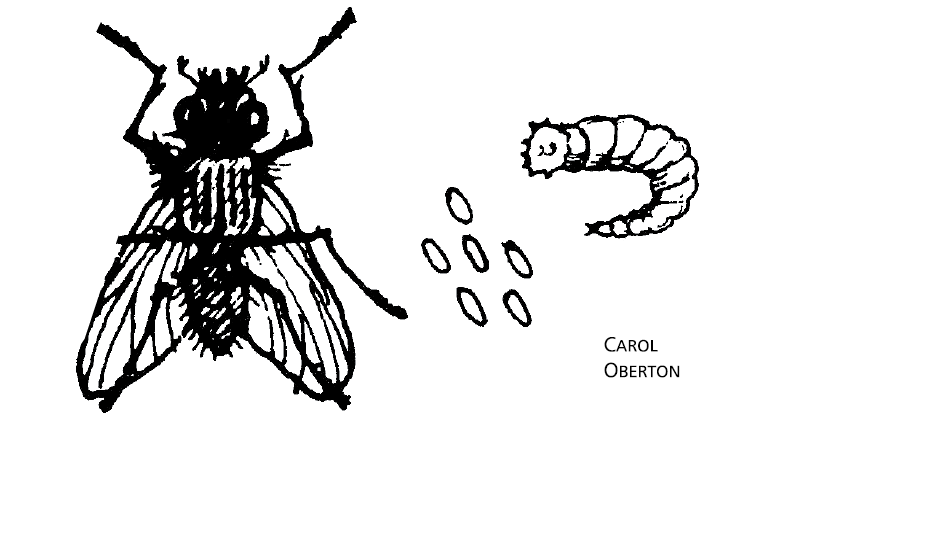

Cabbage maggot (Delia radicum)

The cabbage maggot is a real impediment to the year-round gardener, as the crucifers, which it attacks, represent some of the hardiest and best of the winter crops.

The fall generation of the fly, whose maggots devastate your Chinese cabbages, turnips and radishes, overwinters as small brown pupae in the soil not too far from the host plants. They are usually about three inches below the surface, but can be as deep as five or six.

Each pupa hatches out a dark gray fly, a bit smaller than a house fly, sometime in March or April, depending on locale and the weather that year. According to Bleasdale et al. (see Appendix D), in England egg laying coincides with the blooming of keck, or cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris), a member of the Umbelliferae family and a food source for the adult fly. As far as I can find out, no one has done studies to see what the flies live on locally. Dandelion is the only commonly blooming low plant around here at this time, and it is from a different family. Early yellow mustard? Cherry blossoms, or forsythia perhaps? There must be some flower, as the flies need to feed before they lay eggs.

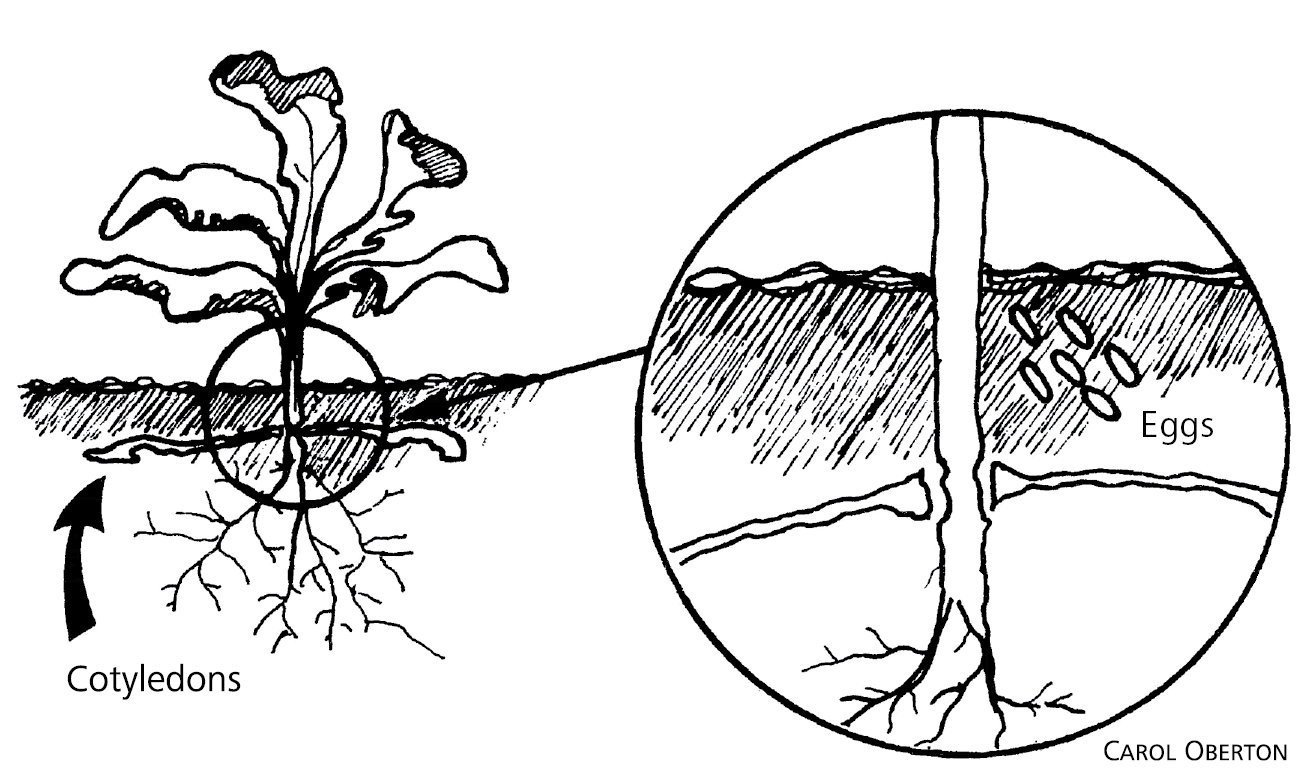

For the first day or so after the flies emerge, they are a bit slow and sit on the soil a lot, but after that you rarely see them unless you catch them in the act of laying eggs by your plants. After mating, the female seeks out cauliflowers, broccolis, radishes and other brassicas and lays her eggs in the earth by the stems. The eggs hatch into maggots, which burrow down to the fine root hairs and commence feeding. After about a month, they pupate and hatch into the midsummer generation of flies. In most places and seasons, this generation is quite light, and little damage occurs to June and July transplants. The fall generation, which usually starts laying right after the mid-August rains in Washington, can be heavier, and a very high percentage of a young crop can be affected.

Maggots sometimes kill plants outright, but just as often they merely stunt them. Plants will look small but normal to the inexperienced gardener, but during sunny, dry spells they will suddenly wilt and keel over. If you then pull up the plants you will find the little white maggots have almost totally destroyed the roots and stems. The plants have just been sitting in the soil.

In a wet year some damaged plants will manage to send out new roots from the stem above the area that has been damaged. However, if your plants have been too badly set back, they will produce no crop, or at best a tiny one, and it’s best to relegate them to the compost heap and plant something else. Make sure to destroy any living maggots you find (check inside the stems, too), as they are the next generation of flies.

The first element of protection against the fly is to ascertain the timing of the generations in your garden. To do this, monitor egg laying by setting out either cauliflowers or broccolis in early April and leaving a few of them unprotected. Then every day, starting on the second day after planting, carefully brush away the top one-half inch of soil within one to three inches of the stems to look for eggs. If you have transplanted properly — with the first leaves, or cotyledons, below soil level — there will be a lot of stem area above the root zone. The eggs are very small, white, cocoon-shaped things, about one millimeter in length. I simply pinch these out and put them on the path where they will dry out and die. In my experience, the eggs have only been a short distance beneath the soil, so it isn’t necessary to disturb the roots when you do this. You can water afterwards with fish or seaweed emulsion if you think your plants need it.

If you start looking just as the flies start laying, you will see only a few eggs at first. In a week or so there may be as many as 12. These higher numbers continue for about a week, and then there is a sudden drop to two or three again. This tells you that the laying is about to stop.

You can keep track of the laying cycle this way for two or three years and make some effort to correlate it to the rest of the environment — early or late, dry or wet season, which plants are in bloom, etc. This will give you an idea of the egg-laying patterns of the flies in your area, and you can time your main-crop brassica sowings to avoid peak laying. Probably the very best of the cultural control methods, this allows you to get most of your fall and winter brassicas off and growing with a minimum of damage. Another technique that uses timing is to sow brassicas in September after the last of the August egg laying and overwinter them under cold frames or, in mild areas, out in rows or beds. There are specific varieties of cabbage for this purpose.

You will still have to protect your early spring sowings of cabbages, broccolis, turnips and mustards, and your late summer sowings of leaf and root brassica crops. To give you some idea of how to do this, I will run through a list of methods people have developed to deal with the cabbage maggot and discuss their feasibility and success — or lack of it! You can choose the ones best suited to your gardening habits and crops.

Placing ashes around transplants and along seedling rows was perhaps the most common barrier method reported by older gardeners. What’s more, those who used it were convinced it works. My own trials and those at the Washington State University Research Station in Puyallup show that there is a slight effect against maggots, but that the ashes can corrode the stems of tender transplants. Ashes must also be replaced after rains or irrigation. Once a transplant is established and the stem has toughened up, ashes might be very effective as long as the fly has not already laid eggs by the plant. I have not tried ashes on direct-seeded crops such as turnips and radishes; reports from those who have are varied. Probably the best technique for these is using row covers.

Another popular barrier material is sawdust. Although it may be beneficial as a mulch, I have not found it effective as a barrier to the fly’s egg laying; however, others think it is.

Tar-paper barriers are, I think, plain nonsense. They often blow away, and the holes around the stems of the transplants are almost always large enough to allow the fly to insert her ovipositor right into the soil. In my tests I almost always found as many eggs underneath the collars as in the soil around unprotected plants. A similar technique, developed at the National Vegetable Research Station (NVRS) in England, is to surround the plant with a compressible substance such as foam carpet underlay. This fits fairly snugly around the stem of the transplants and also acts as a mulch that keeps the root hairs moist and provides a hiding place for predators. These foam collars should be made at least six inches in diameter. The idea here is that the fly, thwarted in her efforts to lay eggs next to the stem, will lay them farther out. In theory, by the time the roots reach the edge of the foam the plants will be big enough to withstand maggot damage.

I tried two kinds of foam collars in the spring of 1982 on broccolis, cauliflowers and cabbages (about 30 plants in all). While the egg laying was heavy, I found large numbers of eggs around the stems of the protected plants (as well as around the controls) and under the foam on the surface of the soil. These were easier to remove than the other eggs because I didn’t have to hunt through the soil for them. Perhaps they might be easier for the helpful rove and carabid beetles to find, too.

At the very end of the laying period, a large percentage of the eggs apparently hatched out; within two weeks, most of the cauliflowers and some of the broccolis were either dwarfed or dead. Most of the remaining broccolis (which had been good, strong plants 15 inches in height) produced only small heads. I wonder how the National Vegetable Research Station had such good luck with this technique. Maybe it used different foam? Perhaps the cool, clear, dry spring of the year I did the trial was an important factor. Plant development had been generally retarded, and the fly activity was a good two weeks later than usual in my garden.

Both the Henry Doubleday Research Association and the NVRS report success with the cottage cheese carton technique, where the plant grows up through a hole made in an upside down carton. Apparently it works by creating a dark space around the base of the plant in which the flies will not lay their eggs.

Most of the above techniques are suitable only for transplants and don’t work for rows of seeded radishes or turnips. Screened beds are a more suitable solution for these and any seedlings, and for transplants. Screening works well if there was no immediately previous crop of infested brassicas in the soil. There shouldn’t be if you are rotating your crops!

Fly screening from the hardware store, tent netting, cheesecloth (at least 16 threads per inch) and commercial row covers all work well. These should be placed over frames, which you can make of wood, wire or PVC pipe. If you use the caterpillar type of cold frame, you can simply take off the plastic at the right time and replace it with screening. Row covers are light enough to just “float” on the plants.

You must make sure there are no holes or gaps through which the flies can crawl. I place boards or rocks on the covers all around the edge of the bed and then cover the edges with soil. The plants usually do better under the covers; protected from the wind and getting extra shade, they produce a leafier and more succulent crop.

Tent netting and row covers have been my favorite and most successful barrier controls against cabbage maggots. In 1981 (and following years), my spring mustards were absolutely maggot-free. They grew luxuriantly under the screening in spite of drought. Watering, weeding and picking them were not problems. The years I have used screening on broccoli, I have had excellent results as long as I was careful to leave no gaps at ground level.

In the area of biological controls, there are several things to try. The first is to encourage the presence of whatever predaceous beetles you happen to have in your environment. Particularly helpful are the Carabidae, or ground beetles, which hide as adults under stones, clods, boards and other garden debris, and whose soil-dwelling larvae can be recognized by their large pincer jaws. This family includes ground beetles in the Calos0ma genus. Most are black or iridescent, but have no special common name. Other beneficial beetle families are the Cicindelidae, or tiger beetles, which I have only seen around here in particularly hot summers and the Staphylinidae, or rove beetles, which are funny little flat guys with cut-off elytra or wing covers. These last are a very large family and can be seen quite early in the year in Northwest gardens. There are good pictures of these in Rodale’s Color Handbook of Garden Insects (see Appendix B) or online. You should learn to recognize them, as they eat all but the adult stages of this pest. The roves are especially useful in this job, eating many maggots, eggs and pupae. Unfortunately, like many predators, beetles often emerge later in the season than the fly and thus are better at handling the latter part of the infestations. They are encouraged by ample organic matter, but then so apparently are the flies. They are sensitive to metaldehyde (Deadline) so don’t use it. Try iron phosphate instead.

In March when the robins and other ground-feeding birds return, you can dig up the soil in all the areas where you had brassicas the preceding summer, fall and winter. Leave it like this for a while. The birds will feed on the worms and pupae and any other grubs they can find.

Several companies sell predatory nematodes. Though some species of nematodes are harmful in the garden, others parasitize soil larvae, apparently those of the fly family as well as the beetles and moths. Many gardeners are starting to try them in this area. Some local gardeners have reported good results; others are not as impressed. I tried them on my Chinese cabbage and fall broccoli several times and the results were not fantastic. But at that time I had a fairly heavy clay soil, and apparently the nematodes don’t migrate as well in clay and heavy silt loams. It seems that at best the control is a question of percentages. You get fewer maggots and therefore less damage, but you do still get some.

Carrot Rust Flies (Psila rosae)

This small fly is a relative of the cabbage root fly and has a similar life cycle. During the early spring (usually April) the adult female lays her eggs in the soil next to young carrots. The maggots hatch out and burrow down to the tap root and eat it and the root hairs off. These damaged carrots either don’t develop or are stunted.

The maggots pupate through the summer and hatch out in August to go through the process again on the late crops. In some areas, there is an even later hatch in October. Damage from the last two cycles is largely in the form of burrows into the carrot’s main root. These make the carrots taste bad and have a rusty color that is sometimes hard to see on carrots but stands out on parsnip, celery and parsley roots, which the maggots also eat.

Strong efforts should be made to control the first generation of flies, as the number of larvae that hatch out will determine the size of the next generation — the one that is so destructive to your winter storage carrots. Some gardeners have reported that raising the alkalinity of the soil with ashes, limestone or agricultural lime is helpful in protecting the early crops. I can’t see exactly why this would deter the maggots. Diatomaceous earth is said to help, too. I haven’t done any controlled tests with these materials. If you use them, work them into the rows before sowing.

Row covers are the method of choice, and really work. But at the end of August, when the rains come again be sure to protect the carrots from slugs; they love to eat the tops and the first inch or two of the root. The rest of it quickly rots.

Sowings after the end of May are usually free of carrot rust flies until the end of August, although you should check this out for your own site. If you time your winter storage carrots to mature before the fall maggots hatch, then lift and store them in a cool, damp situation, you will have next to no damage. The later you harvest carrots in an infested patch, the more damage you will have. You would do well to keep any damaged carrots separate and eat them first.

Another effective cultural control is to remove the wild umbellifers in your neighborhood. Carrot rust fly larvae eat and overwinter by Queen Anne’s lace, poison hemlock and wild parsnip. Their eradication can have a considerable effect, as the adult flies do not go much more than a mile from where they hatch to seek hosts. Sad to lose those beautiful Queen Anne’s lace flowers, though!

Lettuce Root Aphids (Pemphigus bursarius)

Local entomologists have told me that these are not really a problem in western Washington, but when I have shown slides of these gray, mealy aphids — which attack the roots of lettuce and are only seen when you dig up the plants — to gardeners, they say, “Oh, so that’s what that is.” So they do trouble some gardens. Late summer and fall lettuce crops are affected most.

This kind of aphid lives on poplars that grow along rivers and in low, moist areas. During the summer, adult aphids are blown by the wind into your garden. They then burrow into the soil and live around the roots of the lettuces, as well as beets and some other species, weakening the plants. If you have found them to be a serious problem, try the several resistant lettuce varieties that have been developed in Europe.

Slugs and Snails (Gastropods)

Slugs like cool temperatures and high humidity. They are most active in the fall, when you are trying to get the late plantings of hardy crops up and growing, and in the spring when you’re doing the same with the late spring crops. These are also the times when they lay their little pearl-like eggs under boards, decaying matter and in garden debris.

Most varieties of slugs are scavengers and scroungers, preferring wilted, dying vegetation and young new stuff. The main reason they devastate your seedlings is that there isn’t much else around to eat, especially if you have bare plots of soil with a few tiny plants. There are, unfortunately, a few important exceptions, such as the omnivorous little gray slugs which eat anything, any time. Slugs in general seem to prefer cabbages, pansies, marigolds and young squash and cucumbers. In some bad years they will eat onion starts.

I found that slugs abound in greater numbers in the city than in the country. There are so many dark, damp tangles of ivy, clematis, brambles and garbage-filled trash barrels — slug heaven! Even there, though, I could keep the predation down to a reasonable level by getting discarded outer cabbage and lettuce leaves at my local grocery and spreading them down the rows or on the edges of the beds. At night I went out with a flashlight and picked up slugs before retiring. Same thing at dawn. During the day the slugs hid under the leaves, so I got them then, too. This helped, but I had to keep at it. An interesting pamphlet from the Henry Doubleday Research Association, Slugs and the Gardener, indicates that you could catch slugs in your garden every night for a year and not make a dent in the neighborhood population. These mollusks are migratory, so you would have to organize your whole neighborhood into slug patrols. (Not a bad idea!) If you live in the country but next to a wetland you will get nightly migrations of the dark brown Arion ater. If you go out in the early morning with a spray bottle loaded with 50/50 ammonia and water, you can somewhat reduce the population for a day or two. The ammonia breaks down the slime and shrivels them into nothing. (Thanks to Stephanie Feeney for this idea.)

Or you could turn the patrolling over to ducks. Ducks are very fond of slugs. They have a special technique of bill-probing in grass and other vegetation to ferret out low-lying slugs that is very satisfying to watch. Ducks are also friendly, amusing, tasty egg-layers and they fertilize rather than poison the environment.

In terms of the total picture, ducks don’t consume much, if any, nonrenewable energy (none if you let the hens hatch out their own children), and so you are using one more-or-less self-maintaining creature to control another.

If you have a small yard and your ducks show too much of a liking for your garden vegetables, try feeding them greens before you let them in the garden. If this doesn’t work, put up a fence and then just use them to patrol the rest of the property, and you de-slug the garden itself. The ducks will still be worth it due to that migratory tendency of slugs. If you have been using metaldehyde or other slug poisons on your property, you are in danger of losing your ducks! Metaldehyde is poisonous to them and will, at the very least, give them a severe stomach ache. It also poisons rove beetles, frogs and snakes.

Ducks, of course, are better suited to suburban and rural properties than they are to most city ones, so city dwellers might want to use other forms of control.

Interestingly enough, garter snakes are slug predators, too, though they also consume toads, which are another pest control. The balance is probably in favor of the snakes, so leave them be. Hedgehogs eat slugs, too, but they aren’t native to this country. If you are enterprising, maybe you could rent one from a zoo? Chickens don’t really seem to relish slugs, but they will scratch up and eat their eggs if you let them into the fallow areas of the garden.

One useful technique is to mulch low-lying vegetables such as lettuce with substances slugs don’t like to hide under. Wood shavings are good. Hardwoods are best if you can get them. Many gardeners report that barriers of sawdust or wood-shavings in paths and strips around the whole garden help decrease populations in the garden itself. Recent Washington State University research has not demonstrated the effectiveness of this method, though.

Another old trick for slug control is to lay down boards in the garden paths and turn them over every day and stomp on the slugs. I use pansy plants instead of boards — they’re more aesthetic. Slugs love the flowers and hide in great numbers under the plants. I plant pansies in herb beds and other strategic sites around the garden. Plastic traps filled with fermenting yeast seem to work, but put them away from your seedlings.

The recently developed slug fence seems like a good idea. It’s based on the fact that slugs, like rock climbers, have trouble with overhangs. You can make the fence from flashing, gutters or any thin sheet metal you have about. The original design calls for hardware cloth, but small slugs can get through the spaces. Any sort of vegetation leaning against the fence will serve as a ladder, so clean cultivation is the rule. Unfortunately, the larger your garden, the harder it is to surround it with a fence. But these slug fences might be very useful around cold frames (which unfortunately extend the season for slugs as well as for plants). Quicklime is very effective around cold frames too, though it must be renewed after rain and heavy dews. It is good inside propagation boxes, but should not be used too close to the plants.

I have to admit that I like slugs. I think they are beautiful, useful as scavengers and have a right to live, especially the native ones. But I need my garden produce, and I do protect my plants when necessary. So I put out Sluggo, or some other of the iron phosphate brands. These don’t work as well as metaldehyde, but I haven’t heard that they poison frogs, rove beetles or snakes, either.

A publication from Oregon State University, reprinted widely on the World Wide Web, summarizes the conflict between humans and slugs: “To sum a slug, it is magnificently designed to deconstruct. This can be a little unsettling to those who like to reproduce.”

Flea Beetles (Phyllotreta striolata)

Flea beetles are small, black, striped beetles that leap up like fleas from tomato, potato and cabbage plants when you touch or bend over them. They overwinter in garden trash and weeds and emerge in April or May to chew little round holes in your seedlings. Their eggs are small and so are the larvae, which will eat the roots and stems of crops and weeds. There are one or two generations a year. They are worse in some soils and gardens than in others.

Some sources say they are more abundant in wet years, but several years ago, in one of the driest summers in Whatcom County, they devastated both my early and late brassica seedlings. They start on the cotyledons and then go on to the first true leaves, never giving the plants a chance.

If your potatoes, tomatoes and cabbages follow plants that are not hosts for flea beetles, and the area is large enough to prevent them coming in from the edges, you will have few problems with them.

Derris and pyrethrum are said to work, but it’s hard to find a source for them. Note that pyrethrum kills worms and beneficials. In Grow Your Own Fruit and Vegetables, L.D. Hills has an interesting design for a sticky trolley to roll along the rows. The beetles leap up and get stuck.

Cutworms, Climbing Cutworms and Pill Bugs

These can all be a problem, depending on your garden conditions, and the climbing cutworms, a recent introduction, are the worst as they are cold-hardy. Try doing the flashlight at night routine. Cutworms are sensitive to BT and Spinosad, and pill bugs to pyrethrins.

Diseases

Various forms of rot are hazardous to winter crops. Cultural controls and resistant varieties, when available, are your best defenses.

Root canker attacks parsnips when they grow too big in poorly drained soil during the winter. Canker-resistant varieties are available from Suttons and Chase in England and from West Coast Seeds in Canada. You can also sow parsnips later, or more thickly, to get smaller roots. Most important of all, use raised beds or other well-drained areas for your root crops.

Cabbages and leeks will get slimy exteriors after damage from frosts. This is not serious if the underlying tissue is healthy.

Lettuces, those fragile beings so important to the salad-minded, are perhaps the most susceptible to rot. Downy mildew (yellow blotches on the leaves) and botrytis, or gray mold (gray fungus and slime around the stem and bottom leaves), are two of the most important. Reports from organic gardeners in Europe say that volcanic ash and finely ground basalt are useful if they’re spread on the soil when plants are still in the seedling stage, though where to get them, I couldn’t say.

Powdered garden sulfur has seemed to work the same way for me, but it only reduces the problem; it doesn’t eliminate it. In some places where I have gardened, my lettuces were very healthy, so I suspect that soil chemistry or other factors are also involved. It is a good idea to keep lettuce plants well spaced and to make sure the late summer and fall sowings are in well-drained soil. Cold frames should have constant and adequate ventilation. Sowing the right varieties really helps.

Onions are very susceptible to downy mildew in many soils, and the perennial and overwintering types often suffer. Proper spacing in the seedling stage and prompt transplanting are some help. Maybe compost and balanced soil are, too, but the effect of these is more subtle, and I can’t judge that yet.

Onion Rust (Puccinia allii)

A fairly recent arrival on the Northwest coast, this disease affects garlic, onions and, unfortunately, leeks. It just arrived in my garden last year so I don’t know that much about it. The last few La Niñas seem to have set up the right situation for it. It latched on to my Italian Silverskin garlic which doesn’t come out of the ground till the end of July. It hardly touched the earlier hard neck I was growing. And now I notice that the earlier planted leeks, Carentan and Blau Greuner, are infected, but the later planted Bleu de Solaise is almost free of it. Maybe timing is the solution to avoiding it. All the advice is not to put the infected leaves in the compost.

Clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae)

Clubroot is a slime mold specific to the Cruciferae family. It goes into action in late April, enters the roots of recently germinated or transplanted individuals, and as the plants get older, forms large colonies that look like bubbly cauliflower. Most European brassicas just wilt and die, but kales and Asian types are relatively immune. If you have clubroot in your garden, remember not to give anything with soil attached to friends, or lend tools without first washing them. The reverse also holds!

The basics of clubroot are as follows: 1. Without a host, slime mold spores die out in about five years. 2. The organism prefers an acidic, moist and compacted soil. If you don’t grow crucifers in a given bed for five years, nor allow cruciferous weeds to grow in it, nor work it with tools that have soil on them from other beds, your next crop of broccolis will manage to produce. This is a long rotation, but you won’t get much of a crop if you don’t wait. At the same time you must keep all cruciferous plant waste, including weeds, out of the compost. Learn to recognize this large family.

When the time comes to try cabbages again, raise the pH above 60 percent and aerate your soil. The first is achieved by liming at a rate of about 6 pounds per 100 square feet, depending on existing soil pH and texture. Raised beds will aid in aeration and drainage, and in some soils a little coarse sand will help. But digging in plenty of compost is the best.

Another technique, called solarization, consists of watering the soil, covering it with clear plastic, and letting it steam through a week or two of hot sunny weather. Needless to say, this works better south of Salem, Oregon. Up north, it might work by mid-June, if you leave the plastic on for a month, and then plant overwintering brassicas. For directions, look in Rodale’s Pest and Disease Problem Solver (see Appendix B).

For further study of garden pests and solutions see West Coast Gardening: Natural Insect Weed and Disease Control by Linda Gilkeson. Her Backyard Bounty also has a good short section on pests and a chart of pesticides acceptable for use in organic food gardens.

5