Which Vegetables and Herbs to Grow

Introduction

I’ve tried to make this list as comprehensive as possible so that you will learn about the full range of vegetables and herbs suitable for cool season cropping. I don’t suggest you grow all or even most of them in your first years. There are some I haven’t grown myself; information on these comes from others or from books.

I usually don’t give general cultural requirements unless they are uncommon or not available elsewhere. Not only am I trying to keep this book short, but I think that you’ll benefit from reading many gardening books and seed catalogs. No one book says it all. Once you realize there is no single “right” way to make a garden, then you are free to experiment on your own.

Using This Guide

The vegetables are arranged in four sections. First are the members of the Cruciferae family — the important brassicas, including cabbage, kale, broccoli and so on. Next come onions and other vegetables that will survive and even thrive over the maritime Northwest winter. The final group includes herbs suitable for winter cropping. The entries in each section are listed alphabetically; if you’re not sure where to look for a particular species, please refer to the index.

Terminology

“Sow” refers to putting seed in the ground (or pot, plug flat, etc.). The term “plant” refers to putting a plant in the ground (transplanting).

Taxonomy comes from:

Suzanne Ashworth, Seed to Seed: Seed Saving and Growing Techniques for Vegetable Gardeners, The Seed Savers Exchange, 2002.

S.G. Harrison, G.B. Masefield, and Michael Wallis, The Oxford Book of Food Plants, Oxford University Press, 1973.

C. Leo Hitchcock and Arthur Cronquist, Flora of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington Press, 1973.

Hardiness

I have designated each vegetable as very hardy, hardy or half-hardy. Very hardy plants include leeks, kale, salsify and corn salad, which may live through temperatures as low as 0°F (–18°C). Hardy plants such as cabbages and onions will usually survive frosts of 10°F (–12°C). Half-hardy plants die at freezing or a little below (18°F [–8°C] at the most). These designations are for the purposes of this book only; most of the plants mentioned are hardy compared to other garden vegetables. Freeze-out data are from maximum/minimum thermometers in my own and other gardens in the northwestern part of Washington State. At the present writing, the Washington State Extension service has given some actual freeze-out numbers that some varieties will live down to. I have included them here for your interest, but as there are many factors relating to a plant’s winter survival, I would not take them as gospel. Remember that these numbers are approximate. A temperature of 10°F will cause greater damage if it lasts for three days than if it lasts for three hours. Several hard freezes during the winter will cause greater damage to your plants than one. A strong wind along with a low temperature will cause even greater damage. If it snows and then plunges to 10°F, you will get less damage to the covered plants than if it freezes to the same degree without snow cover.

Sowing Dates

When discussing the time to sow certain varieties I often say something like “June in the north, July in the south.” By north I am referring to northern Washington and southern British Columbia; by south, the Willamette Valley. There is about a month’s difference in sowing and planting dates between these two locations, which are approximately 300 miles apart. You will have to adjust these dates for your particular site.

Varieties

Many garden books don’t even list varieties because they change so rapidly. The authors feel there is no point in recommending varieties that may be gone from the market in another five years. They have a good point. Nevertheless, in several places I have broken with this convention for several reasons.

First, it helps gardeners distinguish between summer and cool-season versions of the same vegetable. Second, many breeders have switched over to producing hybrids for industry and therefore so have wholesalers and retailers. If you know the names of the best open-pollinated winter varieties, it will help you recognize them in catalogs, especially in the Garden Seed Inventory published by the Seed Savers Exchange. If you purchase these varieties now, you have some chance of getting to know them and learning how to save their seed before they disappear from the market. Although hybrids are not necessarily bad per se (in fact, many are very superior), they are usually expensive to produce and tightly controlled by the company that produces them and therefore expensive to buy. Third, the name of an old variety can give clues to the nature of present or future ones. If you read in a catalog that a certain cabbage, carrot or kale, hybrid or open-pollinated, has been developed from one you know, you will have some idea of how this new one might perform in your garden.

Unfortunately, in the last few years the seed business has changed dramatically, and many of the old European varieties that work so well in the maritime Northwest are being dropped by commercial seed vendors. Also, the quality of the seed stock of those that have been kept is declining due to lack of breeder attention, improper roguing and other factors. Briefly, companies stand to make far more money from hybrids that they themselves have developed and patented than they do from open-pollinated varieties, which most growers can produce at will. And breeders, as Carol Deppe points out in her excellent book, Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties, are now working to perfect commercial varieties that are grown on vast scales and are usually unsuitable for the home gardener or even the small producer.

All is not totally bleak, however; many alternative small seed companies have started up to deal with this issue. See Appendix A for a list of recommended companies, keeping in mind that both varietal offerings and the companies themselves come and go over the years. To quickly find a source for a specific variety, try an Internet search for a variety name and the word “catalog.” Seed companies will pop up like weeds after a late summer rain.

If you are a beginner, it will help you to begin by trying some of the recommended varieties — though if you are reading this book ten years from now, you may find that catalogs offer entirely different stock. The important thing is to find the equivalent variety for the job, whether it’s an overwintering cabbage or a good cold-frame lettuce. And the second important thing is to become a seed saver. Choose some of the old varieties that do well in your garden and help save them. Read Suzanne Ashworth’s Seed to Seed and the Seed Saving Guide, available free from the Organic Seed Alliance. Join the Seed Savers Exchange and trade seeds.

Since we probably can’t save everything, we should concentrate on whatever we can do best in each of our areas. In the maritime Northwest, our biennials should take high priority. Among these are the cabbages (the fall and winter greens, reds and the Savoys), the late Brussels sprouts, the overwintering cauliflowers. But those are also the more difficult varieties to save, and are better left to a very methodical and experienced professional person. Easier are the kales and the leeks. Annuals such as the Asian cruciferous greens and the winter lettuces can best be selected in winter areas that present a challenge to the varieties but don’t kill them outright. If seed savers in any given area coordinate, they can parcel out endangered varieties to adopt and save. (The Seed Savers Exchange considers a variety endangered when only one company is carrying it.) Also, some people organize Seed Exchange meetings in the late winter; they are lots of fun and educational.

Get to know the people at seed companies in your area that are involved in this process. In short, do what our ancestors had to do in order to have vegetables on their tables.

Crucifers

The Cruciferae family is so large and important to the year-round gardener that it merits its own section. Included in the group are Brassica oleracea (cabbages, broccolis, cauliflowers, Brussels sprouts and some kales), B. rapa (Pe-Tai, Napa, Chihili), the closely related radishes (Raphanus sativus), horseradish (Armoracia rusticana), watercress (Nasturtium officinale) and American winter cress (Barbarea verna).

These species form a horticultural group with similar needs, pests and diseases. When you practice crop rotation, they should, with a few exceptions, be considered as a group and rotated together.

The exceptions are watercress (which belongs in water or moist soil), horseradish and winter cress (which can go in permanent herb beds) and rocket (which is best grown as a catch crop).

Since our most important brassicas evolved in northwest Europe’s maritime climate, they adapt well to our maritime climate and have special pertinence to this region.

Most of the European brassicas are heavy nitrogen feeders, do well with lime and are susceptible to attack by clubroot, cabbage loopers, cabbage maggots and gray aphids. These brassicas usually benefit from transplanting, as it aids their root system. For individual preferences and cultural tips, see the books by Hills, Simons and Shewell-Cooper listed in Appendix D.

The Asian brassicas are a little harder to work with, because their sensitivity to day length makes it necessary to plan their planting times carefully. But they are flavorful and extremely useful for cold-frame work in more severe climates. Hills, Simons, Solomon, Chan and Larkcom have some cultural suggestions, as do the catalogs from Kitazawa, Johnny’s Selected Seeds, West Coast Seeds and Territorial. Rodale Press has put out a good pamphlet, Summary of Cool Weather Crops for Solar Structures, that discusses the use of frames and includes seed sources and recipes.

Note that the crucifers contain goitrogenic substances (they lower the activity of your thyroid, your body’s thermostat), so I’d go slow on them if I were you, or eat seaweed to balance them out. On the other hand, crucifers are now also believed to play an important role in the prevention of cancer, so that’s a plus.

Broccoli (Brassica oleracea)

Broccoli is one of America’s favorite vegetables, and in milder areas it can be harvested almost year round. Gardeners in colder sites will have to do without from early winter until spring. There are good varieties for each season, and you would do well to use each when it grows best.

Broccolis come in green, white and purple (which turns green when cooked). Their leaf shape and resprouting ability are their distinguishing characteristics. In England, winter cauliflowers were popularly called broccoli, kale was known as borecole, and what we usually buy as broccoli in the store was known as Calabrese after the Calabrian region of Italy, where those varieties originated. This, of course, led to a certain amount of confusion in nomenclature, and seed catalogs on different sides of the Atlantic would list the same variety under different headings. Since the establishment of variety legislation by the European Economic Community (EEC), though, this seems to have been straightened out. Cauliflowers are sold as such, and broccoli usually includes Calabrese types as well as the overwintering sprouting broccolis of both colors.

Summer and fall varieties Hardy 18°F (–8°C)

Italian Green Sprouting

DeCicco

Umpqua

These belong to the Calabrese type we are all familiar with. In very mild locations such as Seattle they can not only crop in midsummer, but produce side shoots well into the fall and, in some years, even to Christmas. Temperatures much below 18°F do them in, and their heads are very susceptible to rot from rain. You can also sow in late January or early February in heated frames for an early spring crop. Some of the new commercial varieties have excellent hardiness.

Overwintering varieties Very hardy 10°F (–12°C)

Purple Sprouting

Nine Star Perennial

These are sown in late May to June in the north, later in the south and overwinter in the immature state to form heads in early spring. They are very hardy and have survived 6°F (–14°C) in my garden, withstanding northeasters with much gallantry. They are large plants, taking up a good 30 inches each way, especially in March when they start to produce their small purple or white heads. The heads keep coming for a month or so but get progressively smaller as time goes on. By the time they get as thin as asparagus, the little florets are good in salads. After that, you can pull them up and chop into the compost.

The main problem, other than size, with over-wintering broccolis is that they harbor the gray aphid, which will then have ready access to your young spring transplants. The chance of these colonies overwintering is reduced if you spray the plants with soap solution or other organic treatments in the fall or early spring (see Chapter 4: Sharecroppers).

I have not kept Nine Star Perennial over to see if it really lasts several years as the catalogs say. I don’t know if it would be worth it, as it would interfere with crop rotation and general garden organization. And, of course, it would harbor pests.

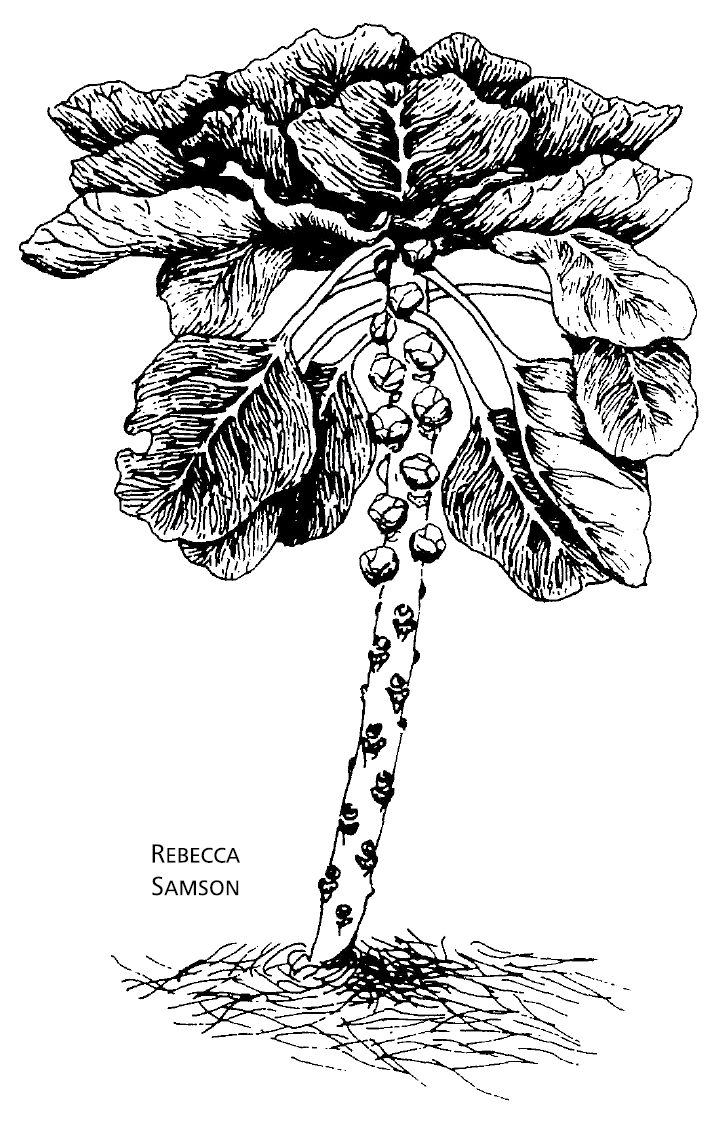

Brussels Sprouts (B. oleracea)

Brussels sprouts, along with kale, parsnips and leeks, are the epitome of winter-hardy vegetables. They are available from October till March. In April you can eat the sprouts as they start to flower; they taste much like broccoli then and are good in stir-fries and salads. I think Brussels sprouts are better sautéed than steamed. They are a superior roasting vegetable and are also excellent in soups as long as you don’t overcook them. Lane Morgan’s Winter Harvest Cookbook has a dynamite recipe for a Brussels sprout curry.

Early varieties Half hardy 10°F (–12°C)

If you like to have a continuous supply of Brussels sprouts from September on, you can start off the season with some of the American types, such as Jade Cross, Long Island or whatever is currently offered.

Personally, I don't want to bother with picking sprouts in the early fall when there is such an abundance of other crops. Also, for some reason I haven't been able to get many of these types to form well for me. The sprouts grow loose heads and, since they are close to the ground and jam-packed together, maggots can come up from the root system in wet falls and tunnel into them. Their tight spacing also makes the sprouts vulnerable to rot, and they are not really hardy. Two more reasons not to grow them for the winter

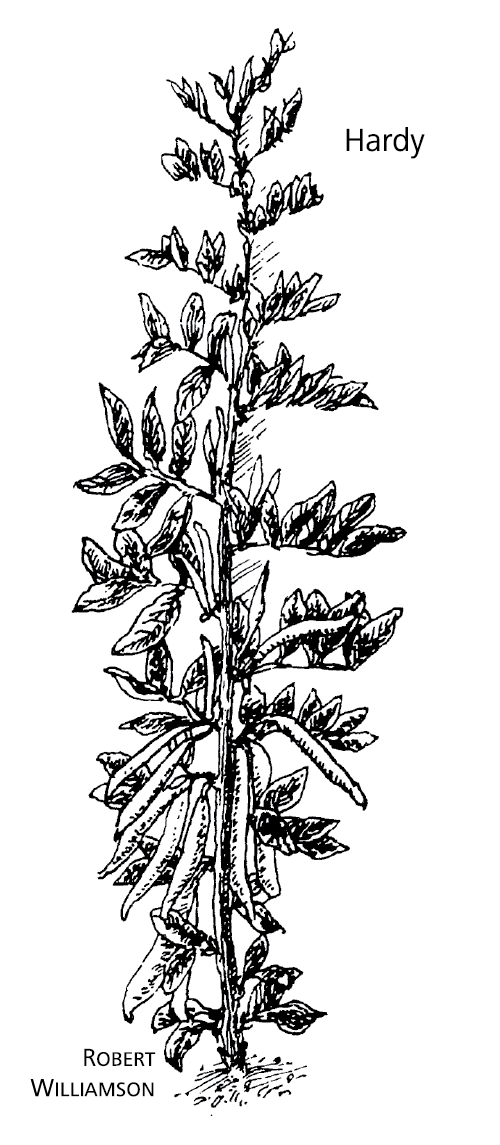

Midseason and late varieties Hardy

Long Island Improved

Roodnerf series

Rubine or Red Ball

A great deal of breeding work has been done with Brussels sprouts. Midseason and late types grow medium to tall in height: 24 to 42 inches. This allows the sprouts to be well spaced along the stems and helps prevent rot. The sprouts are generally small and very tight. The older English varieties tended to have bigger, elongated sprouts with more of that disagreeable, hot “cabbagey” taste.

I was happier with the Dutch-bred Roodnerfs. They are medium tall and less inclined to lean over in the wind than the real giants. They have good-sized, hard, round sprouts with a very sweet flavor. The Roodnerfs also seem more tolerant of imperfect growing conditions. Brussels sprouts in general respond strongly to environmental influences.

Brussels sprouts ... show very wide variation that is caused partly by the environment and partly by genetic differences. This renders selection difficult, and in the past quite numerous commercial strains have failed to meet the requirements of all growers. As a consequence this crop, more than other cole crops, has been subjected to extensive selection by the growers themselves. The resulting growers’ strains are sometimes adapted to the growing conditions in a certain locality. For instance, types selected on a heavy soil may show rank growth and produce loose sprouts when grown on light soils, and strains from a light soil may remain too short stemmed on a heavy soil.

Variety trials have shown that there are also strains that can be satisfactorily grown almost anywhere, and these are attractive to the trade.

— M. Nieuwhof, Cole Crops 1969, p. 79.

Cabbage (B. oleracea)

It is possible to harvest cabbage most of the year if you match varieties with planting dates. Whether you want to eat that much cabbage is another question! I lose interest in them during the summer when there is so much else. But they are useful, very easy to grow, and taste so much better from the garden.

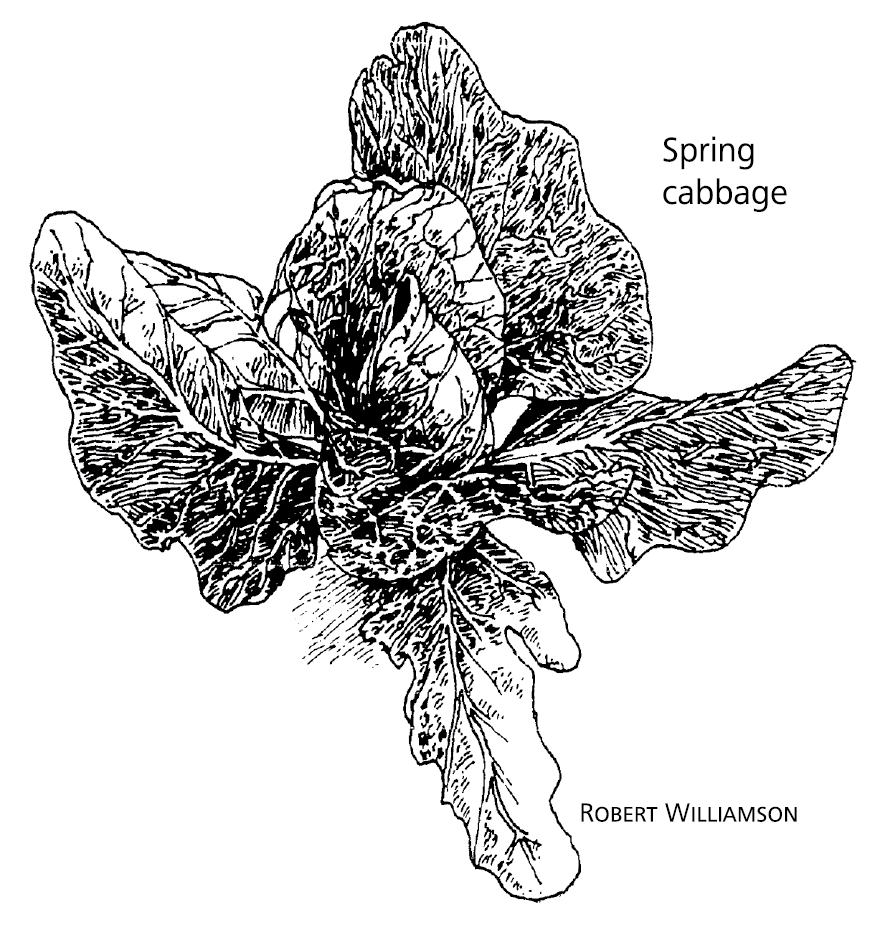

Early Spring Cabbages Hardy

These are quick little cabbages, often with pointed heads, that are sown September and early October and overwintered in cold frames until they can be planted out in February or March. In some very mild districts, you can overwinter them outside. If you don’t grow them well, they tend to be loose and often bolt before they form much of a head, but they are tender, and because April to June is a period rather bereft of greens, I find them worth the effort. Jersey Wakefield is the classic variety currently available in American catalogs. One of the best things about these autumn-sown types is that they are too big and well-established to be much affected by cabbage maggots in the spring — a great bonus!

Green cabbages for standing and storage Hardy 10°F (–12°C)

Sow these, and the Savoys and the reds, in plugs from late April to early May (later in the south) for main-crop cabbages. In the past I used a seed bed (i.e., I grew the seedlings for transplanting in the actual garden on a spare bed) because it was easier to keep them together for watering, feeding and weeding. But plugs in flats are even easier, as long as you have super-good potting soil, and the risk of transplanting shock is far less in the hot days of late June and early July. The trick is to use a plug that is big enough that the young brassica won’t be crowded at the end of the four to six weeks it needs to become big enough to plant out. Crowding young brassicas causes stopping; they become dwarfed, reddish around the edges of the leaves and look gray-green and tough instead of a lovely succulent green as they should (unless, of course, they are red cabbages, but you know what I mean). It’s a waste of time to set stopped brassicas out, and don’t ever waste your money buying them. It’s very common to see them in this state at supermarket nurseries.

I also sow Brussels sprouts, late broccoli, fall purple cauliflower, kale or Purple Sprouting broccoli in these plugs. I sow the overwintering cauliflowers a month later.

A month after sowing, I choose the best plants and put them out in their permanent beds. If you are using the seed-bed method, soak the seedlings well the day before and then do your transplanting on a gray, misty day; if the weather doesn’t oblige, transplant in the evening and keep a fine spray on the seedlings during the hottest hours. The idea is not so much to make water available to their roots (which you’re doing anyhow) but to keep the atmosphere around their leaves cool and moist. This way they are growing again in a couple of days.

The cabbage heads are ready to eat by September or October but will stand in the garden until March in more or less good condition depending on weather and variety. I leave the better looking ones for last; the healthier the plants, the better they will hold up.

If you live in northeaster-territory, you can pull a few cabbages out by their roots and store them in a box or a heap in damp wood shavings or sawdust. They keep fine this way in a shed, and even if they freeze somewhat, they’ll thaw out with little or no damage. You can also use them to make kraut and/or kimchee in gallon jars and store them in the refrigerator when they have finished fermenting.

I used to have many non-hybrid favorites among the winter cabbages, but their seed is hard to get now due to EU variety regulations. Some of these were Glory of Enkhuizen, Christmas Drumhead and the Langedijker series. So you’ll have to try the rather expensive hybrids (admittedly often very good), search among the more conservative catalogs or try the Seed Savers Exchange.

Red cabbages Hardy 10°F (–12°C)

If you live in the USA, you can no longer get seeds from William Dam, which is too bad as the Langedijker Winterkeepers were good fall and winter sorts. Canadians still have access to these varieties. Rodynda, a medium storage red bred in Germany, is available from Turtle Tree.

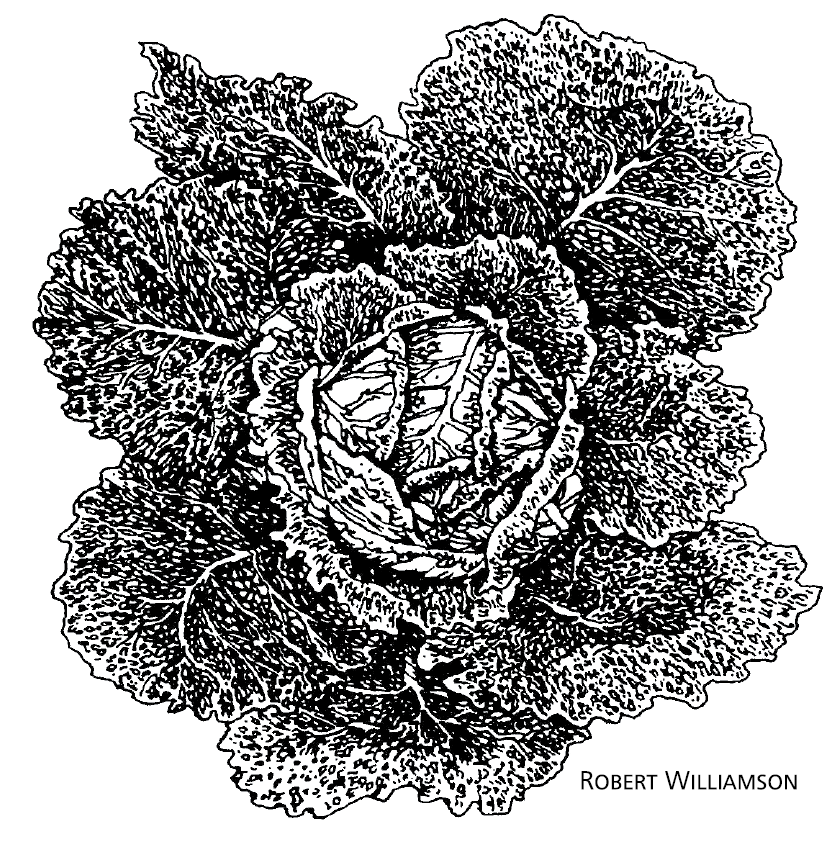

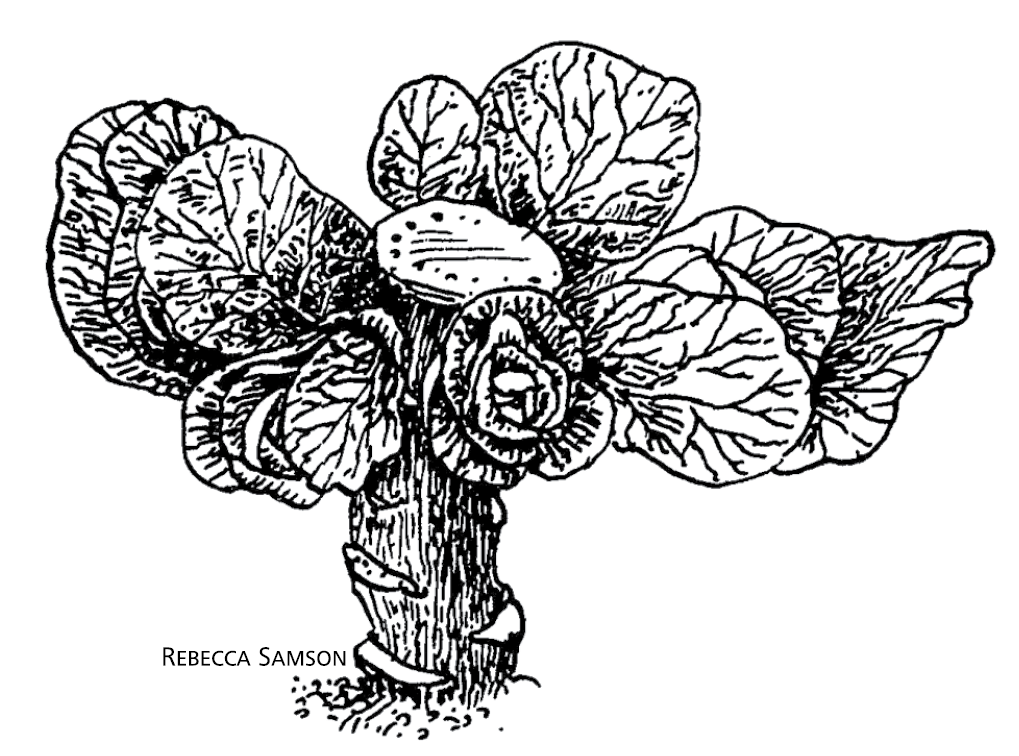

Savoy cabbage Very hardy 8-10°F (–13- –12°C)

Savoy cabbages are still not too well known in America. They are loose, open cabbages and don’t have a very long shelf life, which probably contributes to their lack of popularity. But they taste good, have more green inner leaves than other cabbages, and are certainly worthy of attention by the winter gardener and cook. They are also very beautiful. The old varieties are the hardiest of the cabbages and stand well in the rain and snow.

Their name comes from an area in southeast France and is also used as an adjective to describe the intense crinkling of their leaves. This is thought to impart some extra hardiness to plants that have it (for instance, Cold Resistant Savoy Spinach).

My favorite early Savoys were Kappertjes, which are small (hence, probably, the name Kappertjes, which means capers in Dutch), very early ones for eating in September and October, and Ormskirk, a standard English type that comes in autumn and winter forms. Ormskirk was super hardy and stands until March, or later in a wet, cold spring.

January King is an old standard, a well-deserved favorite, and now one of the few open-pollinated savoys left. Before the EEC rulings, it was just as often listed with the green cabbages, but now it has been settled as a Savoy. It has beautiful red tinges, and it’s tough! (It stands the weather and takes longer cooking to soften up.) January King is also really delicious. It has several hybrid descendants. At this writing, West Coast Seeds carries the original.

Cauliflower (B. oleracea)

Growing summer cauliflower has always been an arduous undertaking for me, but fall and overwintering ones are easier and rewarding. Sow the fall cauliflowers with the main crop cabbages and the overwintering ones a month later in June. Transplant them after a month and keep them good and moist until they start growing again.

If you are a beginning gardener, you might want to avoid cauliflowers in the first years and devote your space to a more productive and reliable crop. Cauliflowers are low in Vitamin A in comparison with other crucifers (though fair in other nutrients) and the winter varieties take up lots of space — three feet each way. If you do decide to grow them, make sure that any manures you add are well composted, that you keep the plants well watered in dry spells and that you transplant them before they get crowded. Hills has an interesting section on cauliflowers in his book Organic gardening. Territorial and West Coast Seeds also have information on growing them.

Fall varieties Hardy

These include such types as Purple Sicilian and Veitch Autumn Giant. They are sown with the main crop cabbages and later transplanted at the same time. They are ready to eat by September and usually done by late November, depending on your locale. In a very mild location, a slightly later sowing will give plants that crop on into December (I harvested Veitch Autumn Giant in January in my Seattle garden), and in English catalogs you could find varieties specifically for this time. I currently garden in the path of the Northeasters so I don’t experiment with them. (That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t!)

The older open-pollinated fall cauliflower varieties are also slipping away from us, though maybe not as fast as the cabbages. West Coast Seeds and Territorial have some as of this writing.

Overwintering types Very hardy

These are sown very late. I used to sow overwintering varieties in June, but the British Columbia research station starts them later and so do the farmers in the Skagit Valley — there must have been something peculiar about my varieties, site or soil. If you want to try them, make some successive sowings through the summer to find the best dates for you. If I sow them much later than June and transplant in July, they are not only hit by drought, but also devastated by cabbage maggots. Commercial growers usually direct-sow and use insecticides and don’t have to worry about this.

There are many varieties of these overwintering cauliflowers: the English Winters, the very fine Walcherins, the Armado series and others. Unfortunately, they are not available in American catalogs. Adaptive Seeds of Oregon has retrieved Leaming English Winter, one heritage variety, from the jaws of death, so you can try it if you wish.

If you have a large family, you will want to put overwintering cauliflowers on 36-inch centers in beds; if you have a small family, try 24 inches or else you won’t be able to eat the monsters at one meal. In a good year, the late April/early May ones are 18 inches across — and if you have even two or three of those ripening at once, you’ve got to trade or give them away. By June they are overwhelming. Planting at later dates also reduces the final size.

Chinese cabbage (B. rapa) Hardy fall types

Chinese cabbage, the big heading Napas, respond best to decreasing day length and temperatures. That makes it a good fall crop and, in mild locales, a winter one.

The Chinese stored their mature cylindrical cabbages through the winter in unheated cold frames made of mud bricks, or in pits covered with mats. This keeps them blanched and in good condition.

Since they are sown in late summer, the plants are seriously bothered by the cabbage maggot, and it pays to make an effort to protect them one way or another. My neighbor Chong (from Korea) has finally found out the correct date for sowing them in my neighborhood: July 15. She and her husband are trying out four different varieties this summer, and they are looking beautiful. She also sows her fall spinaches at this time, and when they turn their soil, the fallen coriander seeds sprout, and so she gets three for the price of one, so to speak.

Collards (B. oleracea acephala) Very hardy 0°F (–18°C)

Vates/Champion

Georgia

Cabbage Collards (US gardeners may have trouble getting seeds for these. William Dam carries them in Canada.)

These small, open cabbages, very popular in the southern US and in black communities, are useful greens in the late winter. They were known as coleworts in England. I suspect they were brought over by the Scots immigrants to Appalachia and selected to survive in the South. There are very interesting varieties from Portugal and Italy, too. Collards can be thought of as transitional varieties between the curly-leaved kales and the "primitive" wild cabbage of Europe. They are naturally hardy, with much variation, and if you grow 20 or so plants of a not overly selected strain, you will see this diversity.

Breeders in the Southeast, where collards are a winter staple, have worked with them more than anyone else. They are grown commercially over much of the Piedmont area, and though often not harvestable in the depths of winter, they are good late fall and early spring crops. According to Lane Morgan, who gardens in Bellingham, Washington, they start pumping out new growth once day length reaches about ten hours. In the Northwest, a mid-July sowing will produce a good crop. They will go down to at least 15° F (–9°C), and in most Northwest winters can be harvested continuously, like kale. They have a similar high vitamin content.

Cress

American Winter Cress, Barbarea verna (common weed) Very hardy

Garden Cress, Lepidium stivum Half hardy

You will often find Barbarea verna (known as American winter cress or upland cress) growing wild. In fact, it thoroughly naturalized itself in my old Seattle garden, where I started it from seed one fall and then ignored it because I found I didn’t like it much. It tastes like a hot watercress. A small, innocuous but weedy plant, it is called shot weed around here. The British sometimes grow it in pots, cut the tops and then throw it on the compost before it goes to seed.

Lepidium sativum, the other cress, is more succulent and is often grown as sprouts (as well as in the garden) in Europe. Hills has a good description of how to do this under a cardboard box. In Europe cress is grown for the market in little plastic trays. Customers take it home, put it on the windowsill or in the fridge, and snip off sections for their salads. It is quite high in nutrients (see Appendix C).

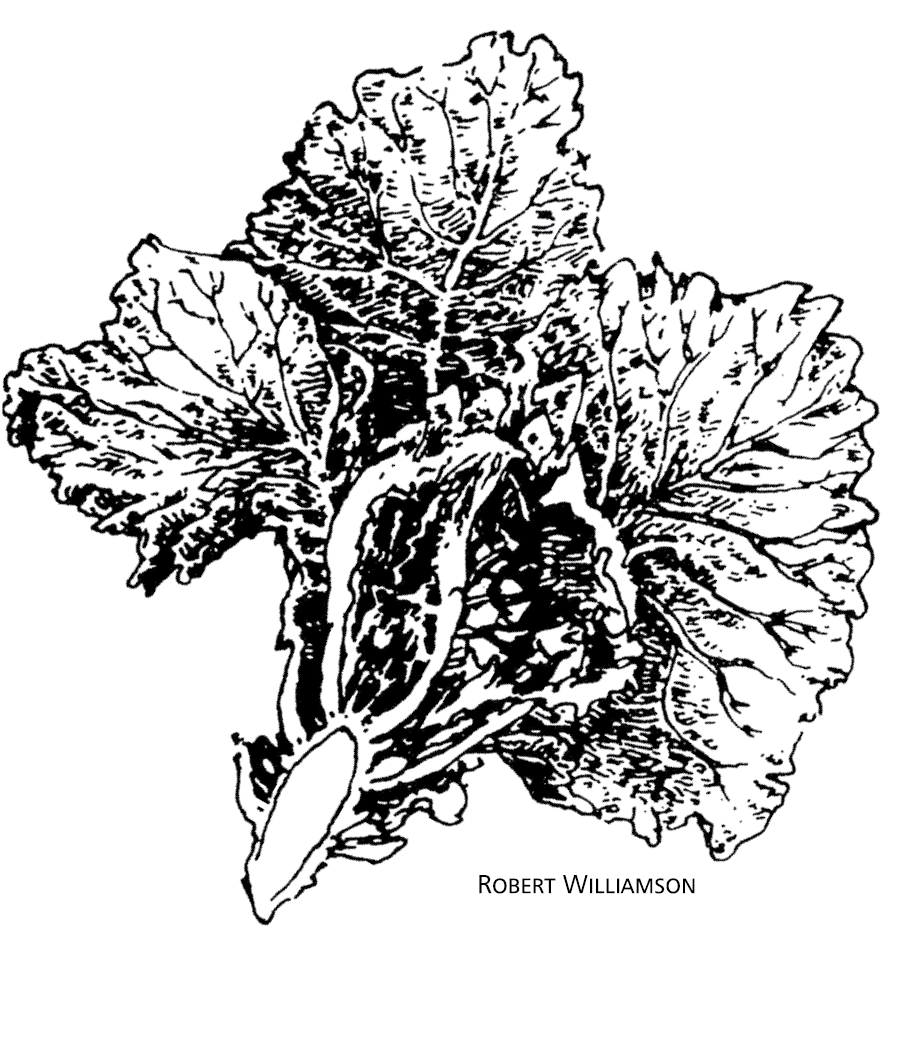

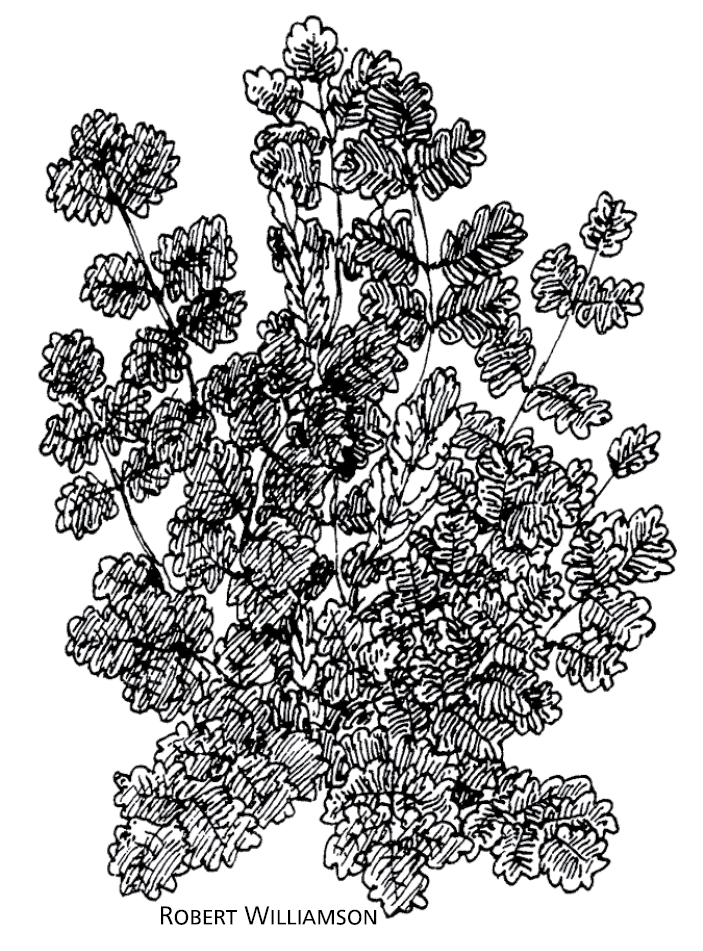

Kale (B. oleracea acephala and B. napus pabularia)

Very hardy 0°F (–18°C)

Kales, along with leeks, rutabagas, parsnips and the hardiest cabbages, formed the mainstay of later-winter vegetable eating for Northern Europeans for many centuries. Gardens in Scotland were known as "kailyards" (since Scotland runs from about 56°N to 59°N, this has interesting implications for southeast Alaskans).

There are many varieties of kale that I have read about but not seen listed in catalogs: old standards of self-sufficient gardeners and farmers that have disappeared along with so many other varieties since the Industrial Revolution with its freezers, trucking and changes in eating patterns. Being so hardy, and so packed with vitamins, it merits your attention (if not midwinter devotion) and a place in your garden. The spring sprouts, tender and broccoli-like, are superb. And the flowering kales, as well as being highly ornamental, are quite palatable.

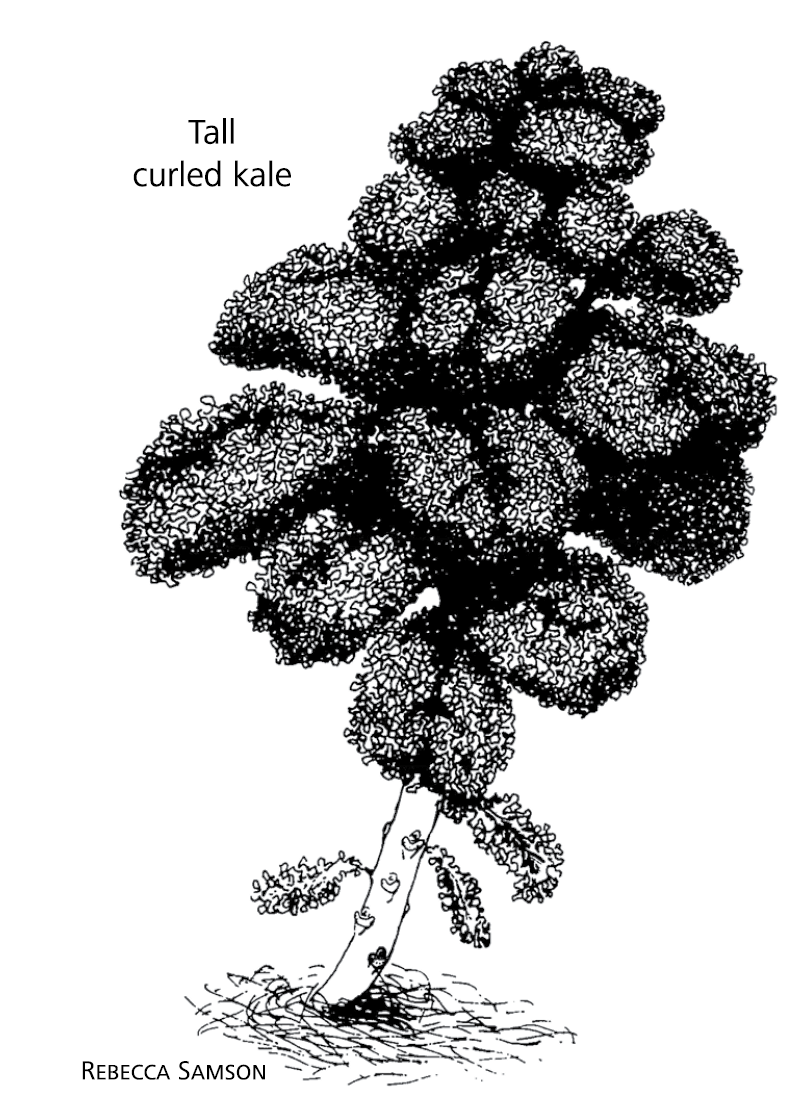

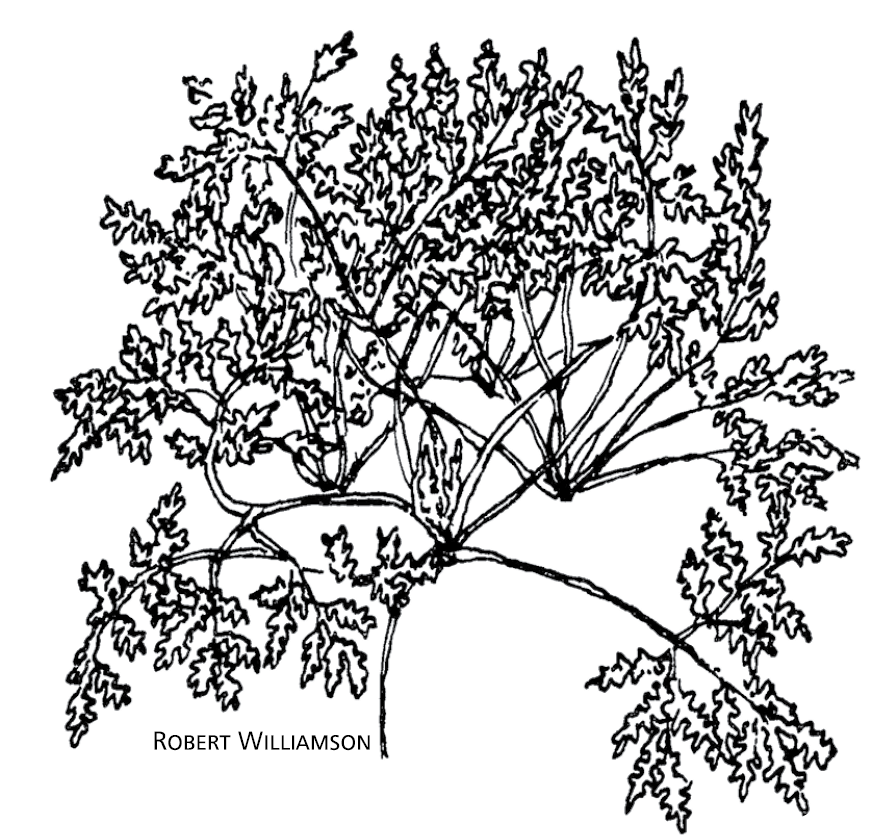

There are two forms of kale. The first stems from B. oleracea and includes Dwarf and Tall Scotch, Semi-dwarf and Tall Curled, Cottager’s, Thousand-head, and now, Tuscan or Dinosaur. Thousand-head is huge and used for stock. Cottager’s was pretty big, too, with lots of red tints to it. Very hardy , it went down to 4°F (–15°C) in my garden with no damage. I didn't think much of the taste, but it was good for the chickens. The others (which are very similar except in height) can be started in May or June in flats or in the cabbage seed bed. They can then be set out at their normal spacing (24 inches between plants) a month later. There are Fl hybrids of curled kale around today, but I don’t see any reason to go that route, especially since it’s so easy to save kale seed (just make sure there aren’t any other B. oleracea relatives flowering at the same time). Adaptive Seeds has rescued a kale from Sutherland (the northern part of Scotland), so that should be worth trying. Turtle Tree Seeds has some German varieties that I am trying this year.

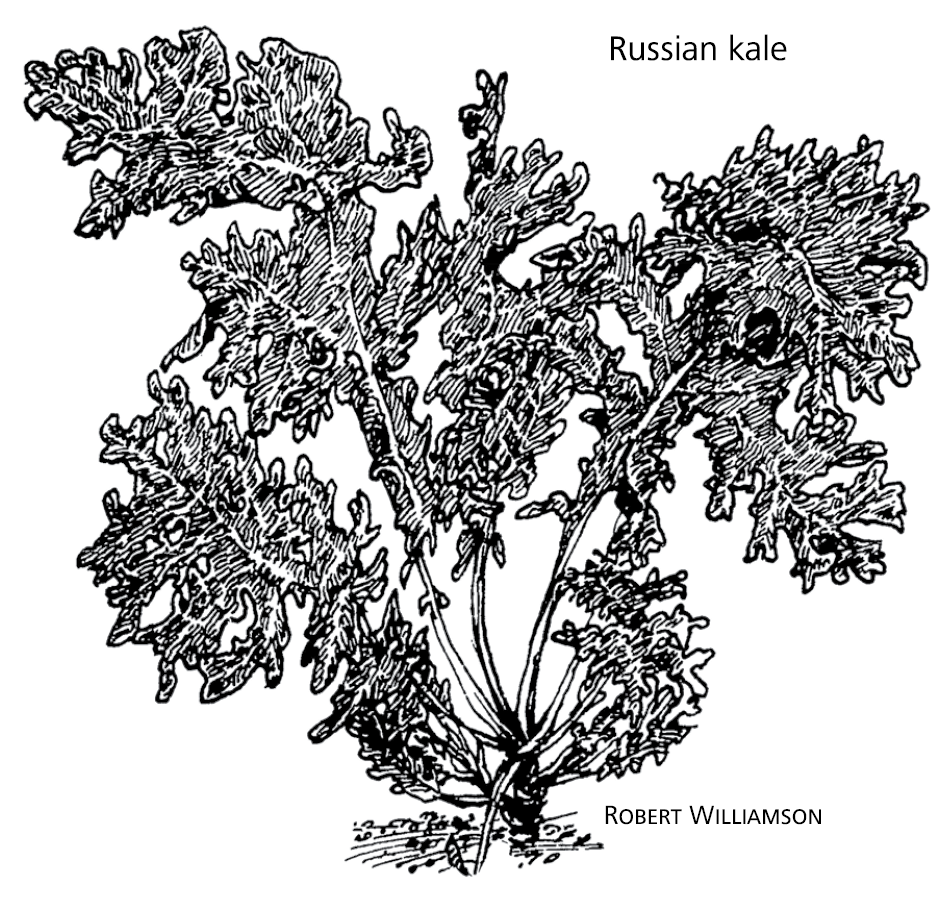

The other kinds of kale do not transplant well. They stem from B. napus and include Siberian, Ragged Jack, Russian, Hanover and Asparagus Kale. These forms are related to the rapes and rutabagas (they have a different number of chromosomes than the B. oleracea types) and include some of the superior salad kales.

T

hese types can be sown directly in July or August on 18-inch centers. If you are worried about germination, sow a few extra seeds and then thin (feed thinnings to the livestock in September or eat them yourself). Unless your soil is awful, don’t manure or fertilize before you sow; the plants will grow too fast and won’t be as hardy.

I used to have three to six plants of the tall curly kale, and two to three of the Siberian, which feeds a two-person family plus five to seven chickens that have partial free range. You can use the curled through March, when it starts to flower and you’ve cut all the sprouts of any size. Then pull it up, turn in the soil, and turn your attention to the Siberian. It will last approximately another month in a cool spring. The flowers of these or any other brassica are delicious in salads, so I usually leave one plant of some type somewhere in the garden. I like dwarf Siberian for eating raw, especially in spring when the new sprouts and leaves are very tender. Some folks I know eat Scotch and the green curled varieties raw too, but I find them tough and strong-flavored (except in the spring), even though they do improve after a few frosts. I prefer them in soups, stews and frittatas, where they are delicious. Russian is a tender, very attractive kale, striking in salads at all times of the year. But it is not terribly hardy and will die out around 25°F (–4°C). Its best quality is that you can start it all through the summer and it won't bolt on you or turn bitter (except perhaps in a very hot July or August).

Many years ago, in a fit of careless abandon, I let the best of the kales and Asian brassicas in my garden go to flower together. Miscegenation! Then I let the seed ripen and fall about. That autumn I had various forms of kale all over the place; it was very interesting. I left them alone, except for thinning them a bit, especially in the beds. A year or so later, I caught on and let it happen every year. I had been doing the same with corn salad for a while. I couldn't see much difference in the varieties that companies offered, and since corn salad is a "weed of cultivation," I figured it wouldn't make much difference. I did the same and had similar results with dill, coriander and amaranth, although with amaranth, the wonderful colored varieties died out, and it all reverted to the plain green weed. I suppose that was because of the shadiness of that particular garden. But since amaranth is high in protein and calcium, and is such a great cooked green, I am happy to have whatever will grow.

In 1996 I met Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seed, Philomath, Oregon. He told me that he does this on purpose for his salad and seed business, only nudging different groups back and forth to produce the blends he wants. "A hybrid swarm," he calls it. "Chaos and evolution in the garden.

Kohlrabi (B. oleracea caulorapa) Half-hardy 15°F (–9°C)

Purple Vienna

Vienna

Superschmeltz

Kohlrabi, or Hungarian turnip as it was sometimes called, is a stem engorgement, not a root, and is mainly a quick summer crop. You can sow as early as the beginning of March under frames and a little later outside. For the fall crop, sow during the end of July and the first bit of August. Apparently, “Superschmeltz,” the current OP favorite, lives up to its name and stores well. The Europeans are always churning out new, less woody versions of kohlrabi, so they will probably be different next year, like new cars.

I have been criticized for my lack of enthusiasm for this crop. So you should look at the catalogs and cookbooks for real descriptions. I don’t need any more crunchy water!

Mustards Hardy 20°F (–7°C)

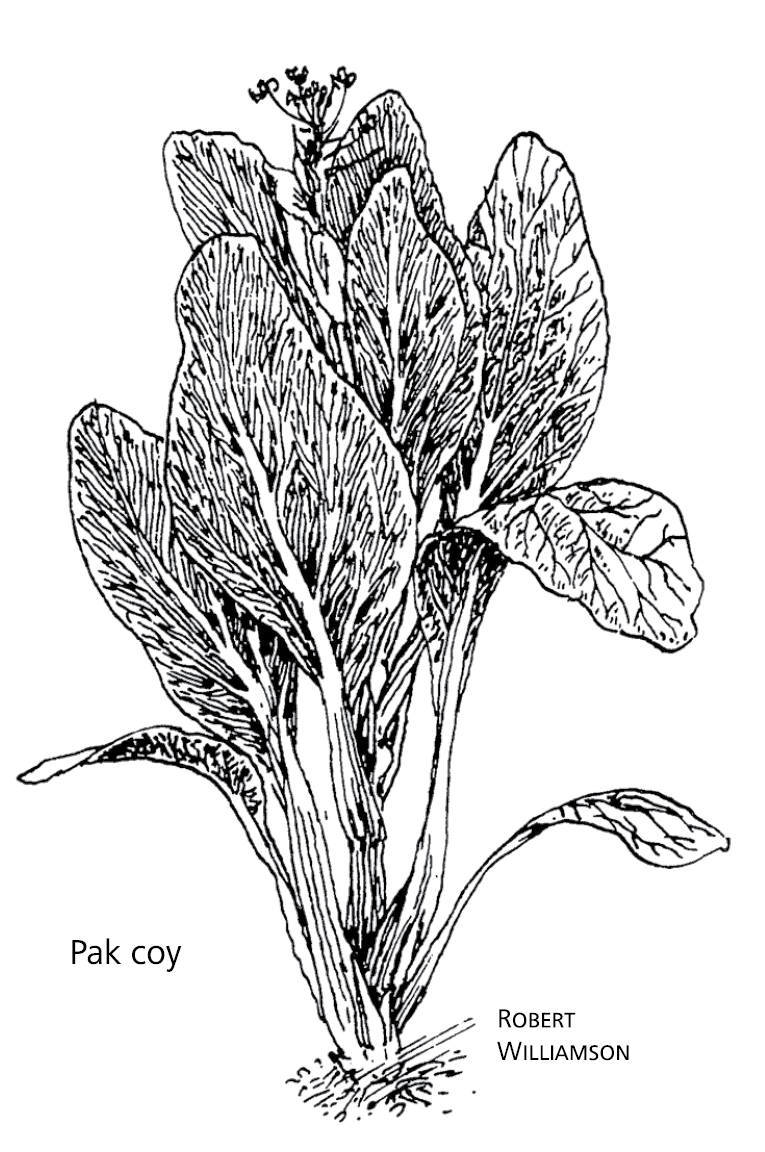

Various forms of Brassica rapa, B. juncea, B. alba, B. japonica and B. pekmensis (Pak Choy, Bok Choy, Green Wave, Tai Tsai, Mizuna, Tendergreen, Santoh Frilled, Price Choy, etc.)

Technically, some of the varieties I list above are not mustards, but Chinese cabbages. So many of them grow in a leafy form rather than a heading form that I’ve lumped them together here. Some seed catalogs list them under “Asian greens,” which is perhaps a clearer designation.

There are many good mustards for early spring greens. The Japanese are doing a lot of breeding work with them, so you can expect to see plenty of new ones in the years to come. I used to sow them at the same time as the turnips under cold frames at the end of February. When the frames came off in April, I would cover the small plants with mosquito netting or Reemay to deter pests. This also shades them a bit, and they grow much leafier than they would out in the open.

Mustards are also good for fall solar frame work in the colder climates. I don’t bother with them in the fall, when there are the Chinese cabbages and so many other bulky brassicas. But they are very useful for small city gardens where the climate is mild. They last well down to 18°F (–8°C). If you do grow them for fall use, you can start in late August and sow till October. The August sowing needs to be protected from the cabbage maggot. Adaptive Seeds and Wild Garden Seed have interesting sounding varieties.

Raab/Rapa (B. rapa) Hardy

This is a small, mustard-like brassica that is sown in late August/early September for an early-spring crop. It’s not terribly hardy. Nor is it very interesting to me. Italians like it, though, so maybe I’m missing something.

Raab is like the Asian brassicas in that it’s quick growing and bred for the greens, buds and flowers. There are quite a few varieties still available that can be tried in the Northwest. A friend says it’s great for stir-fries, and fits into small garden plots well.

Radish (Raphanus sativus) Hardy

China Rose

Black Spanish

Daikon types

European radishes are well known as one of the earliest spring crops. A trip to a farmers market in April or May will overwhelm you with radishes and turnips. They can also be sown under row covers if you are anxious to have them for the fall.

The daikon types, which are often longer and larger than carrots, can be sown in July and early August. (These sowings must also be protected against cabbage maggots.) They can be stored in the ground until Thanksgiving and in areas with mild falls till Christmas. You can also lift and store radishes in damp sand like carrots. I haven’t tried this because I’m not fond of them. But they are essential for kimchee, which gives them a use beyond salads and garnish.

Straddling over the daikon

I pulled it up with all my might: Its root was small.

— Ginko

Rocket/Arugula (Eruca vesicaria satiz) Half-hardy

Rocket is a small, unselected brassica with a nutty taste reminiscent of watercress but even better. It will grow almost anywhere. It is not especially hardy to frost but will germinate in the wettest and coldest of spring soils. Rocket comes charging out of the ground in a couple of days (hence, I suppose, its name) and shows an admirable ability to obtain phosphorus from cold soils. Weather that makes turnip seedlings look sick is nothing to this brassica. I have taken to sowing a few plants among the overwintering cold-frame lettuces, and then again in mid-spring. But it is pretty intense in the summer.

Below is a response from a friend who read the unenthusiastic comments about rocket in my first manuscript. It is a perfect example of the individuality of tastes and gardens.

[Rocket was] my first crop and absolutely delicious despite your disdain! Try it in pocket bread with hummus or in salad with feta cheese and you’ll become a convert. The slugs didn’t touch it, which I suppose is why it was my first crop. (It has beautiful flowers, too!)

— Judy Munger

I must admit that I have become rather more fond of it (a good example of how your tastes can change when you have something available in the garden “off season”). The flowers are just as edible and make a big hit in salads.

Rutabaga/Swede (Brassica napus) Hardy 15°F (–9°C)

Laurentian is the old favorite, at this writing still at West Coast Seeds. Adaptive Seeds think they are the “next big thing” and have several OP varieties. Big yes, but tasty? I found only a limited use for rutabagas because there are so many other winter roots I prefer. But they are fairly hardy, can be left, well mulched, in that big outdoor refrigerator called the garden, and can be grated raw into salads, steamed, mashed and put in soups and stews. They are also a good crunchy surprise in kimchee.

Seakale (Crambe maritima) Very hardy

Lily White

This rather exotic and bitter perennial crucifer grows wild on the seacoasts of Britain. Crowns of it are grown in British gardens or kept in cellars for forcing in the early spring. This produces long white stalks that are used like asparagus or chard (which is often called seakale beet). There are good descriptions of how to do this forcing in current books and online. Seakale is definitely not one of your frontline staples, but a luxury item. I found my plant at a perennial sale, and this rainy season I’m going to spread it about a bit. The blossoms smell great.

Turnip (B. rapa) Very hardy 10°F (–12°C)

There are three main uses for turnips: early spring sowings for roots and tops; late summer sowings for storage roots; and late summer and fall sowings for tops or "greens."

The catalogs list many varieties for February sowings under frames, which you should try if you like turnips.

The yellow varieties, including Golden Ball, Orange Jelly and Golden Perfection (the last two are English), are good for fall roots. They store well and are hardy if left in the ground through the winter. Southerners, who prefer turnip tops for fall and overwintering crops, plant such varieties as Crawford, Purple Top and All Top. Nutritionally speaking they get the better deal, as there are more vitamins and minerals in the tops than the bottoms. The tops are nutritionally superior to spinach also, and the roots have far more calcium and vitamin A than potatoes. Most catalogs offer some form of turnip.

Watercress (Watercress nasturtium) Hardy

This is found in ditches and streams even in such cold areas as the Midwest. Watercress is easy to start from either seed or cuttings. If you can get a bunch of it from a farmer at a local market, try rooting it in water or very moist sand. It will produce well in any spot with rich soil that you can keep moist through the summer.

Watercress is not particularly hardy, though when it grows in running water it is protected from light frosts. It crops best in the early spring and fall. It will self-sow like mad if allowed to go to seed in the summer.

In fact, it is so weedy and vigorous and moves downstream at such an alarming rate that I question the wisdom of allowing it in your favorite stream. Sure is good in salads and soups, though and makes fine sandwiches!

Onions

Onions are such a wonderful and staple vegetable that it’s comforting to know that you can have them all year round — green or bulb, as you prefer.

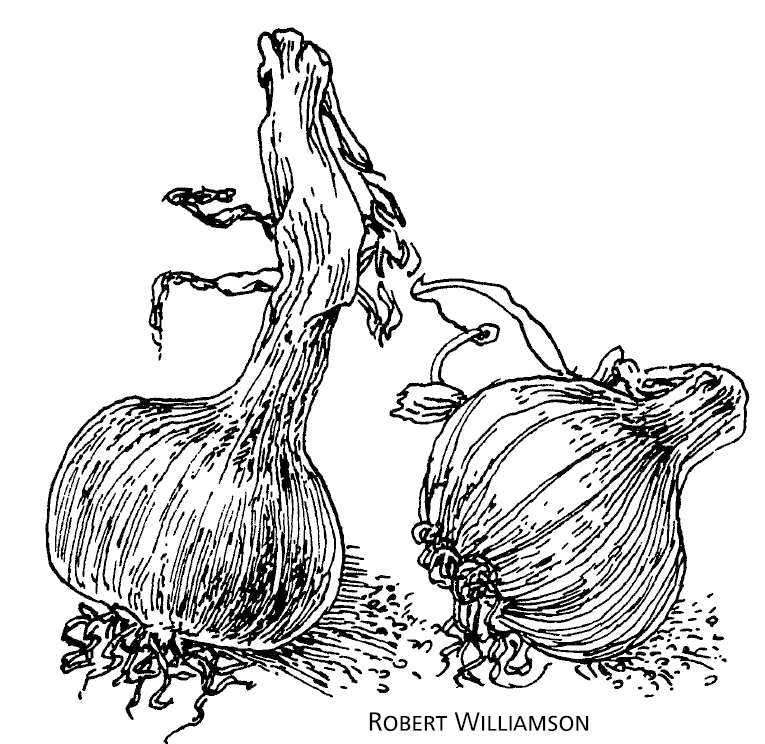

Garlic (Allium sativum) Very hardy 0°F (–18°C)

If you plant garlic cloves in October or November, they will put up green shoots just like onions. These are milder than the cloves and go well in salads, sauces, omelets and so on. Separate the ones for cutting from your main garlic crop, as cutting robs the new cloves that are forming. There are two main types of garlic, the soft stem and the hard neck which sends up a seed stalk or scape in the early summer. These need to be removed and are good to eat.

In the last ten years there has been a welcome proliferation of varieties from all over Europe and Asia: Bogatyr, Chesnook Red, Siberian, German Extra Hardy, etc. Find a local grower and listen to their recommendations.

Unfortunately, garlic on our side of the mountains is quite susceptible to onion rust, which attacks all members of this family. Crop rotation, adequate levels of potassium, not too much nitrogen and spraying with an organic fungicide as a preventative will help. But cool temperatures and high humidity induce the disease and cold springs bring it on. An early harvested hard-neck variety may escape damage.

Leeks (Allium ampeloprasum) Very hardy

I have come to treasure leeks in the last few years. They are so hardy, so tasty, so attractive and, in our area, not bothered by much. They fill the gap if you run out of bulb onions, and make welcome gifts and trade items. They also have a unique flavor and texture and are good stir-fried, baked, pickled, in soups and in many other dishes. I never seem to grow enough.

They are slow growing and, like onions, delicate and small for the first two months. It is a good idea to start them in seed beds or flats in April. In June, lift them, trim the tops and roots, and plant them at six to eight inches apart. I can get three or four rows in my 36-inch beds. This gives me slightly smaller leeks, but I prefer them that way. Garden books will tell you to hill up around the growing plants to blanch more of the shaft. Unless your soil is very soggy, it’s easier to transplant them into a trench and then fill it in as they grow, keeping the dirt below the point where the leaves branch out to reduce cleaning time at harvest.

Like the cabbages and several other winter vegetables, leeks come in fall and deep-winter varieties. As might be expected, the fall varieties are less hardy, but they emphasize height, bulk and tenderness. They are also often a paler green. The winter ones are stockier, with that dark blue-green color I have come to associate with the hardiest of winter crops. They have a higher dry matter content and higher mineral and vitamin levels. Today most seed catalogs will help you differentiate between the fall and winter leeks, but 20 years ago this was not always the case.

Nowadays I don’t have the space for fall leeks, so I can’t recommend any new varieties — you’ll have to do your own experiments. Among the winter ones, Carentan was my personal favorite for a long time. This started in the fierce winter of 1978–79, when it had an 80 percent survival rate in the trials. It has a nice flavor and is tender enough for salads, though it doesn’t get very large. It also has no bulge at the base of the shaft, and so is easier to lift from the soil and to clean. Now I grow more Blue de Solaise, a very sturdy variety that goes back to the 19th century. Wild Garden Seed offers a Winter Mix of open pollinated varieties that Frank Morton got from a breeder in Belgium, so if you have room, you could select favorites for yourself.

Overwintering Onions (A. cepa) Very hardy

If you are in a hurry and haven’t got starts of any of the other types, you can plant onion sets, garlic cloves or shallots for a supply of greens through the winter. They can be planted any time from early September through October and pulled for greens as desired.

In the northern part of our range, Walla Walla Sweet, a hardy type, is sown in a seed bed at the very end of July or in the first week of August. Once they are large enough (the end of September, usually), you can plant them out at a normal spacing to overwinter. In the spring they are commonly sold as bundles of transplants, and also in pots. Pull them as green onions from about April on. They begin to bulb up in May and are usually ready for harvest as dried bulbs by mid- to late June. It is important to observe the correct sowing date so that they are large enough to make it through the winter but not so large that they bolt the following spring. These are not super keepers, but they are so sweet in the summer that they are hard to do without. They should last until your regular bulb onions are ready.

Japanese Onions (Scallions) (A. fistulosum, A. cepa)

Very hardy

The true scallions, Allium fistulosum, are non-bulbing perennials, called Welsh onions in England. This misnomer comes from the Old English Welisc, meaning “foreign” or “strange,” and of course it is also the root of the Anglo-Saxons’ name for Wales. An ethnocentric slur, but in the case of the onions, appropriate enough, as they came from Asia. In their original form, they grow in clumps with small, slightly swollen bottoms and multiply like chives. Known as cong bai, they were for centuries the common garden onion of China and Japan, and are considered therapeutic against colds. The Japanese have done a lot of varietal work on them. Some other forms of scallions are actually Allium cepa, and in the main these are not hardy. Some are, and you can use them if you want, but they are not perennial, so you will have to buy seed and sow every year. Unless there is a disease problem, it’s much easier to just maintain a bed of A. fistulosum.

To start off a scallion patch, sow seed any time in spring or early summer. They flower in midsummer and then die down. With the September-October rains, they start growing and are usable again. Growth slows around winter solstice, but they are available again until June or sometimes July following a rainy spring. Their flowers, which come on in June, are good for salads.

There are several commercial permutations of the scallion emphasizing different traits. Some aren’t hardy, but Evergreen Hardy White (aka Nabuka) has made it through even New England winters.

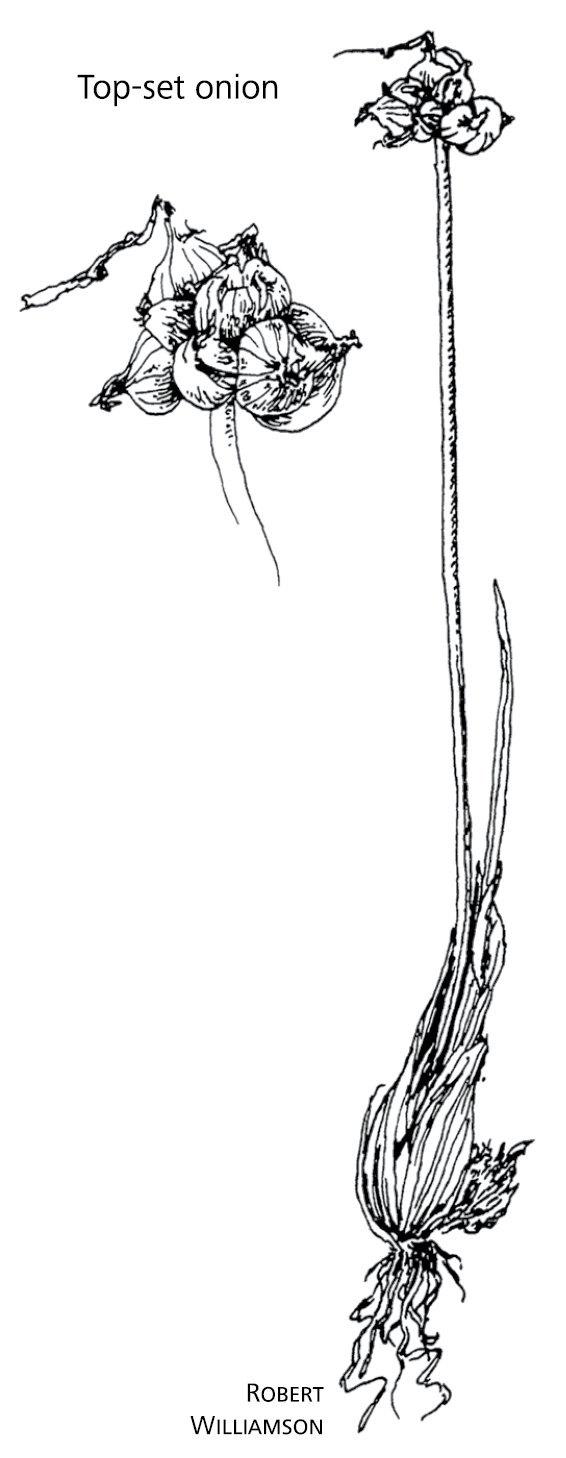

Top-Set Onions (A. cepa proliferum) Very hardy

Egyptian onions, tree onions, multipliers

Although these onions are very hardy and tasty, I have given up growing them. I didn’t find them very prolific compared to the hardy scallions. But if you want to, you can propagate them two ways:

1) Buy top sets, or bulblets (little bulbs that form at the top of the stalk where the flowers should be, or sometimes in coexistence with them). You can harvest these in midsummer when they are ripe and plant them for greens in the fall. They will then turn into next year’s mature onions. The stalks die down, leaving the big bulbs in the soil.

2) Harvest three or four of the big bottom bulbs, leaving one in place to multiply, or harvest them all and select the best to replant for reproduction. These bulbs are strong flavored and at their best when dug from the soil in midwinter.

Once you have these growing in your garden, you should have them for a long time, as they are very hardy and persistent and don’t require much attention, not even weeding. I had top onions in Wisconsin under an old apple tree, where they propagated themselves happily, year after year, surviving temperatures of –30°F (–34°C) and three feet of snow.

Other Vegetables

Beets (Beta vulgaris) Hardy 15°F (–9°F)

Winterkeeper and Lutz are two standard winter beets and are still available. I haven't found much difference between them. Robuschka is also an excellent sweet keeper. Any of the small beet varieties will also work, if mulched. Beets for keeping should be sown in late June or early July so they have time to mature their big, tender, sweet roots. Both Lutz and Winterkeeper have pale green leaves that taste rather like chard. If you have frosts that go much below 15°F, you should mulch or else lift and store them in a cool place.

Broad Bean/Fava (Vicia faba) 15°F (–9°F)

Windsor

As you can see from the Latin name, favas are vetches and were, along with peas, the hardy legume of choice in Mediterranean areas. Some people, most commonly those of Mediterranean, African, Asian and Middle Eastern descent, lack an enzyme required to digest fava beans, a disorder known as favism. Symptoms can be severe, including ruptured red blood cells, leading to jaundice and anemia that in rare cases can be fatal. The effects can also be triggered by inhaling the pollen, so individuals with favism should avoid the plants in bloom as well as the beans themselves.

Favas should be sown as early as possible in the new year. In mild areas a November sowing will also work, though rot and mice can be problems. A sowing in March or April is fine if you don’t have bean aphid (sometimes erroneously called black fly) in your area.

Bean aphids can overwinter on bigleaf maples; if you have those and they are infested, you should try for a November or January sowing so that you will have well-grown plants by the time the aphids make their appearance in the spring. Then you can just cut back the tender tops which the aphids attack. In hard-frost areas, where November and January sowings may not survive, try a February sowing and aphid patrols in infested areas (see Sharecroppers).

In either case, favas are ready before the snap beans (Phaseolus vu1garis) and sometimes before the peas. I think they’re best when the seeds are the size of a large thumbnail; later the skin gets tough (though the seed inside still tastes good). Some books recommend eating the pods too when they are the size of small snap beans, but I find them bitter even when that small. The big dried beans are good in soups and stews but need long cooking. At any size, they are a good protein source and the small-seeded ones make a good cover crop.

Burdock (Arctium minus) Very hardy

I used to collect burdock wild in the Midwest. The roots and young, tender shoots are strange tasting but good. The Italians, Chinese, Japanese and Juliette de Bairacli-Levy place great store in its medicinal qualities. It’s good in soups, stews and stir-fries.

Sow in the spring (it’s a slow grower) and gather from fall onwards. However, don’t let it go to seed and escape to your land, especially if you keep sheep; it’s a pernicious weed and the burrs will make the wool unusable. Pulling cockleburs out of your own hair and clothes is no fun either.

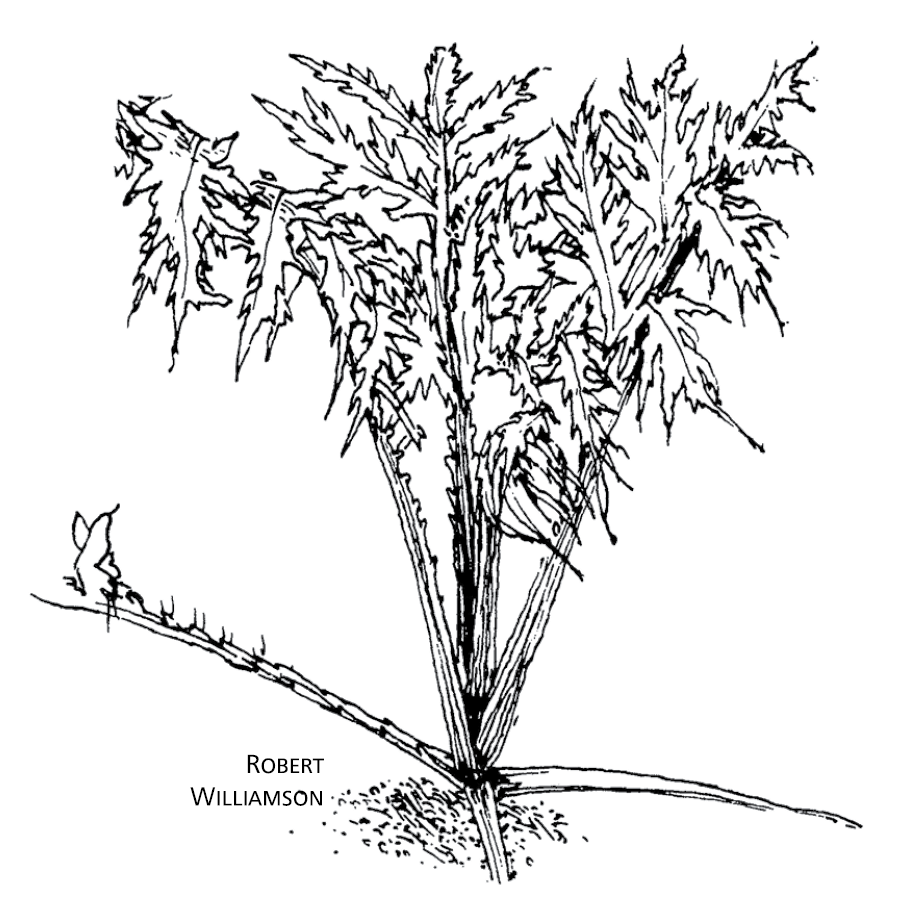

Cardoons (Cynara cardunculus) Half–hardy

Cardoons are a tall relative of the globe artichoke, with a similar flavor. With cardoons you eat the stalks rather than the flower buds, so you get more food per plant. In the fall, their stalks can be blanched by wrapping with paper to reduce bitterness. However, in moist maritime winters the plants last longer without that interference in air circulation. The tradeoff comes in the cooking, when unblanched stalks must be cooked in a couple changes of water to be really palatable. The Oxford Book of Food Plants, and especially Angelo Pellegrini’s The Food Lover’s Garden have good descriptions of how to grow these.

Cardoons are sown in May and harvested in November. After the first harvest in the fall you can let them overwinter for a good final crop in spring. The seeds generally don’t mature as far north as Washington State.

I tried growing cardoons and was rather disappointed in them. They took up a lot of space and I found them fuzzy and bitter; nothing I did seemed to overcome these problems. I was not inspired to try again. If you are, you had better confer with an expert.

Carrots (Daucus carota) Hardy 15°F (–9°C) if mulched

In my first garden in Seattle, I inadvertently left carrots in the ground all winter and they were great till April. Unfortunately, every other place I've gardened in the Northwest has been host to plagues of carrot rust flies, nasty relatives of the cabbage maggot. When their larvae attack, they leave behind long, gray- and rust-colored tunnels that make the carrot bitter as well as ugly. Also, the slugs love to eat the tops off, killing the whole plant. So now if I grow them, I harvest them and store them in damp sand or peat. If you don’t have rust fly (or wireworm) and want to store carrots in the ground, mulch them well, for they are ruined by temperatures lower than 10°F (–12°C).

For several years I tried different varieties of carrots for summer eating and storage. One type I tried kept like mad but was rather tasteless. We ended up not eating it. Then I discovered that my favorite munching carrot, a Nantes type, stored admirably. I just have to time the sowings so that the storage crop is ready at the first hard frost but doesn’t overmature and split. It goes into storage at peak quality and comes out almost the same. By all means, try some of the European storage types, but if you find you don’t like them as well as your favorite summer carrot, try the above technique.

Though carrots are a good source of vitamin A, I prefer to eat squash in the winter; more result for less effort.

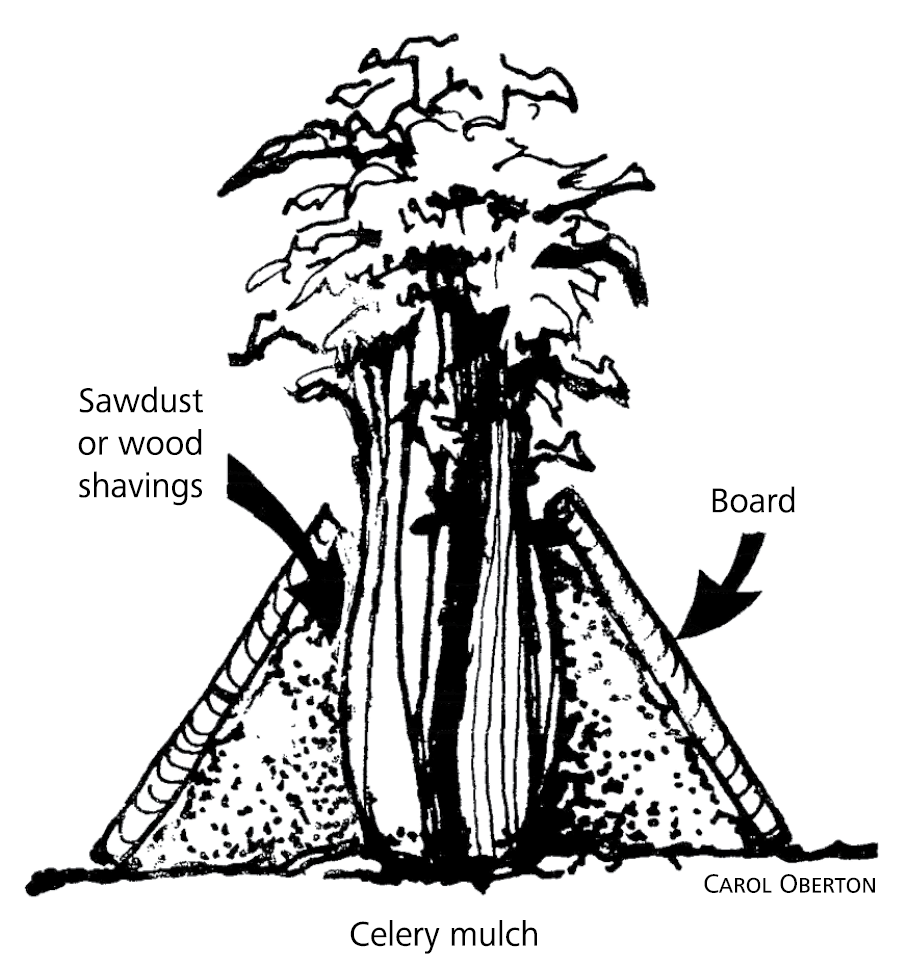

Celery (Apium graveolens) Half-hardy

In my Seattle garden, most Utah type celery plants overwintered without any difficulty, just a few frozen outer leaves. They tasted very strong, though, and were mostly good for soups and stews (but very good for that). A few plants lived three years, which surprised me since they are supposed to be biennial. I suppose it’s because I took the central flower stalk to eat before it bloomed.

At temperatures much below 18°F (–8°C) the centers die out, so if you live in a cold spot and want to carry them over, try a high mulch (or put them in cold frames, cloches or low hoops). If the outer leaves die back before you use them, be sure to take them off. Mushy, rotten stalks will rot the core of the plant. I have not had much luck with mulching regular celery in Whatcom County. I used the hardier leaf celeries (Apium graveolens var. secalinum) instead. They are small and hollow-stemmed, designed for flavoring soups and other cooked dishes, not for munching raw. I started them along with the celeriac and then put the plants in a protected place, such as a cold frame or a bed against a south wall. Here they are quite happy most winters and produce new leaves from the center as I pick the outer ones.

I also tried growing the winter celeries that were available in Suttons and other English catalogs. For the life of me, I can’t see why they bother with them. The ones I tried had tough, bitter leaves like those of celeriac, but no swollen root. They didn’t seem as hardy as the leaf celeries, and they were much more fuss to grow. They are supposed to be for blanching by mulching in a trench. I’m afraid I find that too much work.

Celeriac (Apium graveolens) Hardy

20°F (–7°C); 10°F (–12°C) if mulched

Celeriac is one of my favorite winter roots. It's very versatile: tasty in soups and stews, grated fresh into salads or steamed with a cream sauce. You can use it to replace celery stalk in recipes. It has the same flavor and more bulk, minus the strings and crunchy texture. I never seem to grow enough.

Celeriac needs to be started early in flats and kept in a frame until the weather warms. Up north you can start seedlings in April in flats. Since they need a very rich, moisture-retentive soil, I line the flat with a layer of newspaper and then add two inches of rich compost. Then I put in two inches of potting soil and firm it down. The seeds go on top of this and are kept fairly moist both before and after they germinate. They are quite slow growing, but when they get crowded in the flat, I put them into individual pots. In June, the celeriac is planted out into its permanent home. By using this method I have been able to get mature roots by harvest time, even in hard clay soil. At this writing many garden stores carry starts.

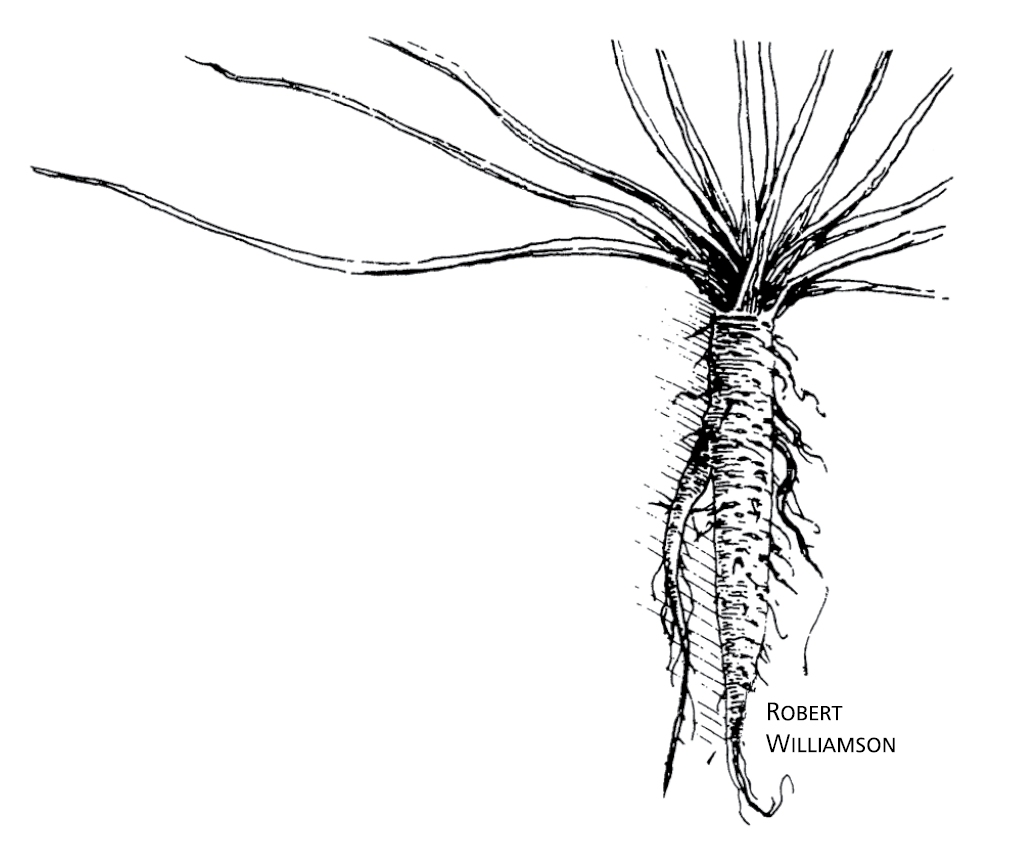

If you like large roots, give them plenty of room, eight to ten inches in the row. At harvest, they come out of the ground looking like Medusa, even Brilliant, the current favorite, and you have to sacrifice lots of side roots to be able to clean the dirt away.

You can store the roots dry in buckets but damp sand is preferable. In milder districts like the islands or cities, they can be left in the ground. They should be mulched if the temperature drops much below 18°F (–8°C).

Chickweed (Stellaria media) Very hardy

Considered a weed in most gardens, chickweed makes an excellent living green mulch for Brussels sprouts and broccolis, though it can overwhelm lettuce and onions if you have good soil. Chickweed is bothersome in the cool seasons of the year, and in a rainy summer it never dies back. It is a serious weed in heavy soils. Regular and frequent cultivation is the only way to keep it under control. If by some chance you don’t have chickweed in your garden, pick it in the fields or from a friend’s garden.

The size of the leaf indicates the fertility of the soil; chickweed grown on rich soils has bigger leaves that are more succulent and have better flavor. I clip the stems with scissors to avoid pulling the lower parts of the runners out of the dirt and use the plant in salads. J. de Bairacli-Levy says it has medicinal qualities, and apparently it is high in iron.

Dear Binda,

Did you know that chickweed was still a real vegetable in medieval times? I once read an old guild statute, where all the different courses of a meal were described, which the wife of a Master Craftsman had to serve to the journeymen, and there was also Mierlein, or chickweed, mentioned. How times change!

Ute Grimlund

Marysville, Washington

Two other less familiar greens for the salad bowl are Buck’s Horn (Plantago coronopus) and Sculpit (Silene inflata). Both are apparently very hardy additions and are offered by Adaptive Seeds. I am looking forward to trying Buck’s Horn, though my wildflower books show it as pretty small. We already have two bigger European plantains here, which some people harvest, and the broad-leaved one is quite a weed in lawns — if you happen to think lawns should only be grass. Sculpit, an aromatic herb from Europe, apparently doubles as a cooked green.

Chicory (Cichorium intybus) Very hardy

Chicories are in the same family as lettuce, and cousins to endives. I often get them mixed up. But you can refer to the seed catalogs to set you straight. They are wilder and slower-growing and, like lettuce, they are at their most useful as cool season crops and are grown in several forms for different purposes. Varieties for all purposes are usually sown in the four weeks directly following the summer solstice.

If you are inspired to try the forcing types, read one of the older English gardening books mentioned in Appendix D for complete instructions. Joy Larkcom has a good section on all the chicories in The Salad Garden. You would do well to read this book anyhow for its complete and beautiful treatment of salads. Johnny’s and Wild Garden Seeds have a lot of good varieties.

Leaf chicories are sown in June in a fairly good soil and kept well weeded. They should be thinned to six inches apart in the row. By late September, they should form heads. You can harvest these as you want until the November rains, or longer if you cover them. They keep for months in the refrigerator in a plastic bag as long as they are free of disease and dry on the outside as they go in. Their bitterness decreases with storage. If you have a mild climate, you could leave them out in the garden. They will take a lot of cold under row covers. I like the leaf chicories in salads mixed with other greens. They have a great texture. The red-streaked types are especially beautiful. They are also good grilled and braised; both treatments modify their bitterness to a tasty counterpoint to other flavors.

The older varieties came in many types — some for big leafy heads, some for small rosette types, some for tight heads with self-blanched centers. Even within a given type there can be a lot of variation (as is true of many open-pollinated vegetables). If you grow ten Red Veronas, you might have three or four that don’t head. These will be more or less a loss, as the outer leaves will be rather tough. But the other good heads will make the effort worthwhile.

The other breeding innovation has been among the red heading varieties, commonly called radicchio in this country. These have been bred to be more tolerant of varying day length, so you can, with care, sow them early in the spring and get red heads. (Formerly, the red came on mostly with cooler weather.) John Navasio of Organic Seed Alliance is testing various chicories for hardiness (see Seeds of Italy, Appendix A).

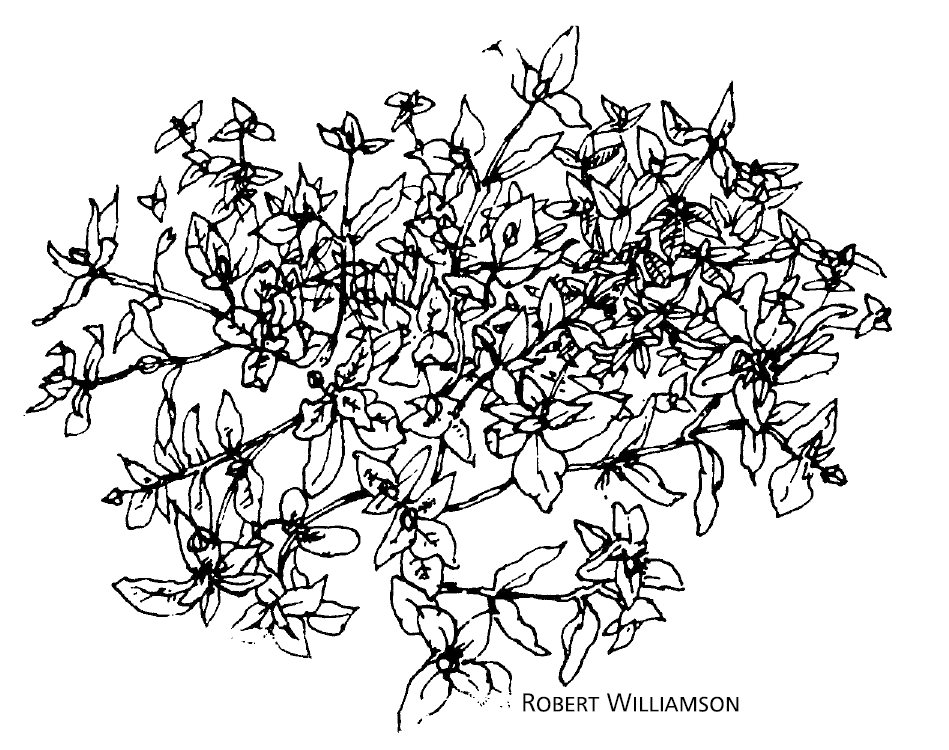

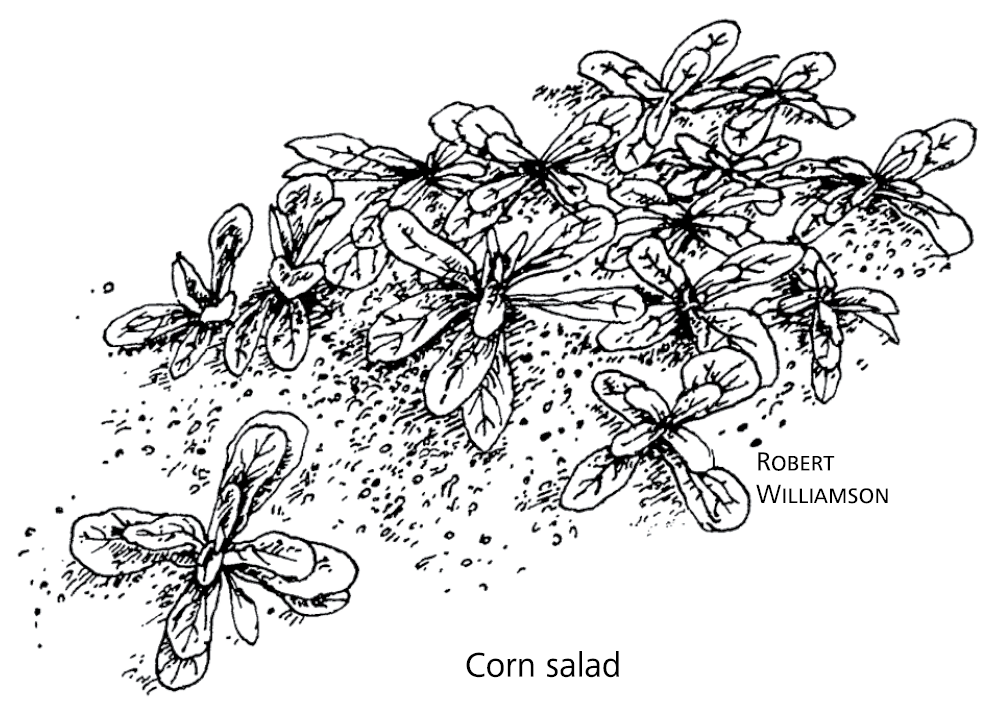

Corn Salad/Máche/Lamb’s Lettuce (Valerienella locusta)

Very hardy

Garden corn salad was derived from a weed in the “corn” (grain) fields of Europe. It is a three-inch-high plant with a very soft, distinctive flavor. As it is a winter annual, it germinates after the late summer or fall rains and overwinters in the rosette form. In spring it puts on a lot of growth, sending out three or four flower stalks from each plant. Although it’s small, I think it is one of the better winter crops. In Holland they have whole greenhouses full of corn salad for market, and consequently there are many Dutch varieties. English and French catalogs also list many types.

I like it in salads from September until the end of April, but it is most useful from January through April when there is a shortage of salad material. Even in its spring growth spurt, corn salad does not get bitter like lettuce. The flowers are a pale blue and just as delicious as the rest of the plant.

If you are growing corn salad for the first time, sow it thinly in late July, or just after the first heavy August rains. You can also make a September sowing in milder or more southern parts. I have clumps of it established in my herb beds and other parts of the garden too. I just let it go to seed on its own. As the soil cools down, the seedlings emerge where they will. It’s very handy not having to worry about sowing it! If you want to save seed, spread newspapers under the plants to catch the seed, as it ripens unevenly and drops to the ground over a month’s time. I just bundle the long, trailing stems together in one spot and let the seed fall. It gets spread around when I clear the bed for the next crop.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Very hardy

Another weed, dandelion is very good for helping your body recover from the midwinter doldrums from February through April. You can dig the young plants and steam the greens, or pick the tiny unopened flower buds and eat them raw in salads. The blanched leaves make a very acceptable salad addition, and a cleansing tea can be made from the roots.

Endive/Escarole (Cichorium endivia) Half-hardy

Curly endive and the flatter-leaved escarole are good fall and early winter crops, especially under frames. I prefer the Batavian varieties, as the hearts blanch well and sweeten as winter progresses. They are not very hardy, though, and should be kept under cover except in mild areas without much winter rain. If you like to eat the whole head at once, rather than picking the outer leaves, you can blanch (whiten) the plants by putting a flower pot over one head at a time. The centers self-blanch to some degree.

Sow endive and escarole in June or early July to get big heads. If you miss these sowings and are going to grow them under cover, you can sow as late as August in the north.

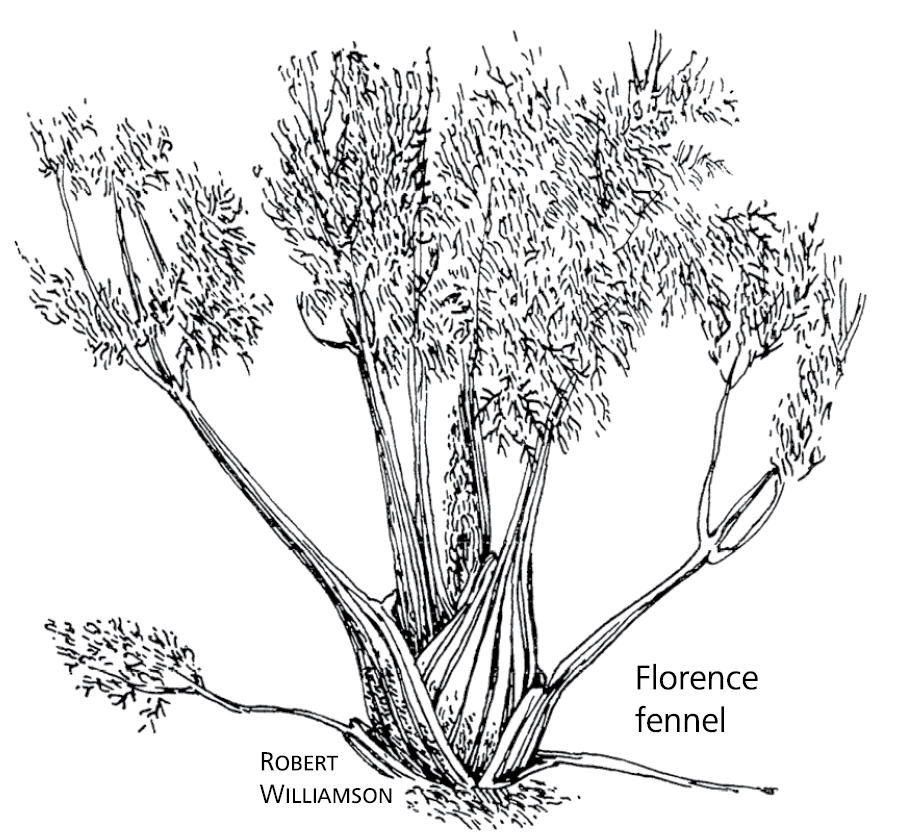

Florence Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) Hardy

Italian in origin and only recently found for sale outside specialty markets, Florence fennel, or finocchio, is now attracting more attention by local gardeners and cooks. Sown in early- to mid-July, it grows somewhat like celery with a funny, swollen base. Cut off the leaves and eat them raw in salads or steam them, or sauté them in a little butter — marvelous and succulent.

I avoided Florence fennel at first because I’m not terribly fond of fennel-seed flavor, but this almost disappears in the cooking. The plants will go through several light frosts and last until November in the north (perhaps later in the south or other milder areas).

For non-bulbing fennel, see the Herbs section.

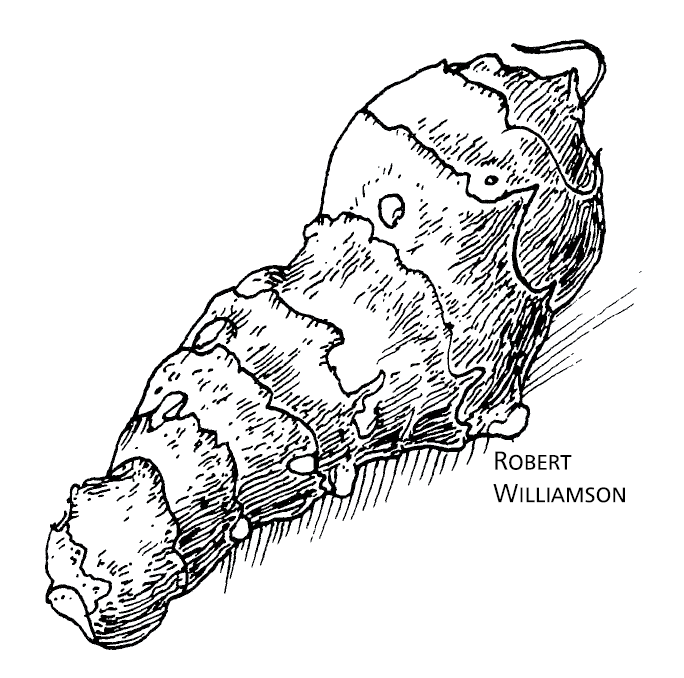

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) Very hardy

This perennial species of sunflower produces a large quantity of tubers that can be left in the ground all winter. The plants are very weedy and tall; keep them well away from, and to the north of, the rest of the garden. The tubers are good raw in salads or lightly sautéed. Boiled, they are even easier to overcook than potatoes. Some people cannot digest the kind of starch they contain, so just eat a smal amount at first.

Get some healthy-looking tubers from a local co-op or supplier. Most seed companies carry them now; some have many interesting varieties. Stampede, the type found in supermarkets, is extremely knobby and a chore to clean and peel. Fuseau varieties, which are beginning to show up at farmers markets and specialty stores, look more like fingerling potatoes and are much easier to deal with in the kitchen. They can be planted in the ground any time from October until May, but they won’t be ready for eating until the following fall. Then they can be dug as wanted from October until April. The tubers store well in plastic bags in the refrigerator but only for about a week. Mice and slugs like them, but the plants almost always produce more tubers than you can possibly eat anyhow.

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) Hardy

Thanks to the general passion for lettuce, breeders produce many different varieties every year, and many of them are suited to fall, winter and early spring production. At this writing, The Cook’s Garden has a good selection of lettuces of all types for every season. It is possible to sow lettuce in any month from February until October, either in cold frames or outside. To have a continuous supply, you only need five or six sowings timed to your situation and microclimate. The Dutch, French, and English breeders did most of the early work with cool-season varieties, and some of the better ones came from them. But several “garden store variety” American ones, such as Oakleaf and Prizehead, also perform well. Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seed has brought lettuces up to date in the Northwest. You would do well to look through their catalog and try those varieties.

Early Spring Varieties

There are many good varieties for sowing under frames in February. I sometimes start the seedlings among the overwintered lettuces and early peas to save on space. Then I move some of them out in April when the frames are getting crowded and it is warm enough for them to do well. Really, this is an easy time to produce lettuce under a frame; the days are getting longer and warmer, boosting vitality so much that disease is usually not a problem.

Fall Varieties

Sowings in mid-August will provide lettuces for September through December, and later under frames. These sowings are difficult ones to get going, due to the summer heat and dryness. If you have a rainy break, the soil should be cool enough to germinate the lettuce. Otherwise, make your sowings between two and four in the afternoon and water well. The seed will have the cool night to begin germination. This technique, recommended by Bleasdale and Salter in Know and Grow Vegetables, is based on the particular dormancy response of lettuce seed to heat. You can also shade the soil.

Whichever variety does well for you, keep it well spaced (on nine-inch centers). I find that in the north I have to cover this set of lettuce by mid-October if I want it to last through the winter. More often, because of the rot problem, I just let it freeze and go without lettuce until the October-sown varieties under glass start to produce in March. I guess I enjoy having a break from lettuce. I focus instead on grated carrots, corn salad, celeraic, Chinese cabbage and sprouts for my salads. If you would like lettuce at this time and live in an area with frequent hard freezes, keep some rugs or mats on hand to put over your frames when the temperature drops.

Overwintering Varieties

If you were away in August or too busy to sow fall lettuce then, you can still make a sowing under frames in September and October that will overwinter and begin to produce extra leaves by early March and whole heads by the middle of April. I find this batch very useful, as I begin to enjoy lettuce again just about this time. Good varieties that may be available include Kwiek, Prizehead, Marvel of Four Seasons, Rouge d’hiver, Pirat, Red Montpelier, Royal Oakleaf, Winter Density, Blushed Butter Oak, Crisp Mint, Double Density and Little Gem. It’s very interesting to watch these little lettuce seedlings slowly come up to size through the winter and then race away in February and March to form heads.

New Zealand Spinach (Tetragonia expansa) Hardy

I don’t grow New Zealand spinach because I’m not fond of it, but those who do tell me that it is as cold-hardy as it is heat-resistant. Apparently, in a mild fall it will last until Christmas.

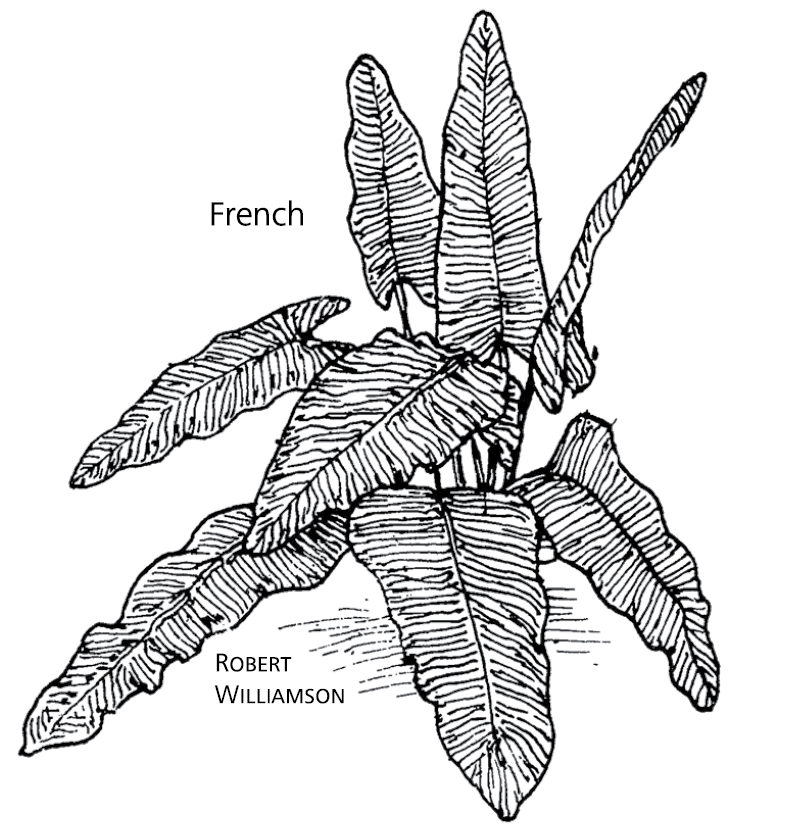

Parsley (Petroselinum crispum) Very hardy

Parsley is a highly nutritious vegetable. I find curled parsley too strong tasting in the heat of summer, but by fall it has sweetened up with the rains and cool nights. The only trouble is that most American varieties are bred for tenderness and won’t stand up to later cold weather. The best I’ve tried are the European varieties Bravour and Darki, which do well all winter. Forest Green seems to be the current favorite in catalogs. You’ll find it listed among the herbs.

I am most fond of plain parsley. Sometimes seed catalogs don’t make a clear distinction between the small, plain parsley and the very large Italian type (perhaps because the commercial growers don’t). The latter grows up to two feet high, almost on the celery level, and has a rather strong flavor. It’s immensely productive. I don’t find it a very good type for the winter herb garden, but if you have a big family, perhaps you could keep up with it. Plain parsley is productive enough as it is, though like most other plants, it slows down around midwinter. In my past gardens it proved hardier than American curled sorts, though it wasn’t much better than the European winter varieties. If you have a strain of plain parsley that you like, try selecting for winter hardiness — you could end up with a good thing. Wild Garden Seed offers “Survivor Italian”.

Sowing dates for winter cropping are the same as those for summer use. You can also sow later in June, but you will get smaller plants. I grow most of my parsley in a well-protected flower bed, where it self-sows. I have both curled and plain, and they look lovely among the blossoms. Occasionally I put in a new plant if there aren’t enough seedlings. Parsley flowers look great in mixed bouquets.

Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) Very hardy 0°F (–18°C)

Parsnips were the potatoes of Europe before Columbus and all that. For awhile they were in disregard, but in fact they have many uses. They are delicious grated in stir-fries, soups, stews and cakes, as well as baked or just plain steamed. They are very hardy, though in heavy, wet soil deficient in lime, they are vulnerable to a form of rot called canker. If your parsnips show signs of this, make raised beds, lime well, sow later and use resistant varieties such as White Gem and Avonresister. Closer sowings, maybe an inch and a half on center, give smaller roots which are easier to deal with and taste better. Cobham Improved works well for me.

In the north, parsnips can be sown in April or May, and in the south until June or July if you want very small ones. Make sure to keep them well weeded. A mulch helps if you have fine enough material. Parsnips should be planted in a bed that was well dug and manured for a previous crop. Some people react to chemicals in the leaves, so be aware.

Peas (Pisum sativum) Not hardy

It is theoretically possible to make a July sowing of pod peas and get a fall crop just before the fall frosts. The problem is that it is hard to keep these moisture-loving, cool-weather plants going through the rigors of the hottest part of the summer. Even if you do manage this, there is a virus in the Northwest, called pea enation, that will cripple most varieties. A few resistant types have been released. I’ve tried some of them, and so far I’d say it’s not worth the trouble if you live in a pea-growing district where the enation is rampant. But if you live in an out-of-the-way corner where there is no enation, or not much, and you love peas, you might try them. Territorial and Nichols have both carried resistant varieties. Also check with your local extension agent.

Austrian peas, which are sold for green manure, turn out to have edible vines. And they are very hardy! You don’t have to make a separate sowing, just add them into your cover crop mix and harvest at will.

Rapunzel (Campanula ranunculus)

A venerable German salad green, with roots that look rather like a small daikon. The greens look much like arugula, whose weedy properties the plants might just possibly share.

Salsify/Oyster Plant (Tragopogon porrifolius) Very hardy 0°F (–18°C)

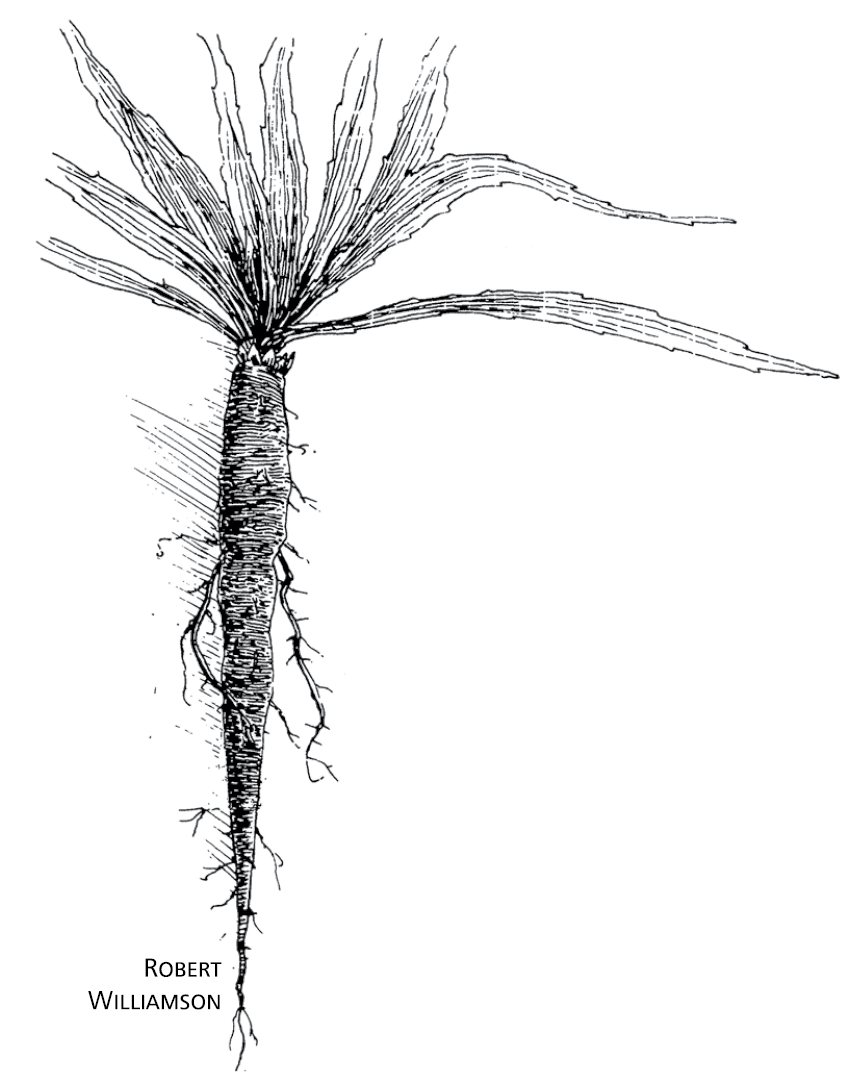

I find that salsify, a member of the daisy family, is a good alternative to parsnip. I like it best sautéed or in soup. It isn’t super sweet like parsnips, and it has a very rich flavor. Sow thickly in April (later sowings germinate poorly), water only during droughts and keep weeded — that’s all there is to it.

In the spring, the new leaves are good cooked or as a salad green. Salsify is a biennial, so if you want to save your own seed, just leave one plant and it will shoot up four to five feet by May and show its purple flowers through June mornings. The seeds come in a ball like dandelions (and are just as weedy), so catch them before they shatter in a wind on dry July days.

Scorzonera (Scorzonera hispanica) Very hardy

Scorzonera, a close relative of salsify, is a perennial with black skin and yellow flowers. The difference in flavor between the two is subtle, and I’m not sure I could tell them apart blindfolded. However, scorzonera does have straighter, longer roots and, in my experience, makes a heavier crop. You can leave it in the ground for two years; the roots just get bigger.

Several people have reported harvesting the leaves and liking them.

The cultural requirements are the same as for salsify, but I think deep digging would really be merited here. The roots can be up to 18 inches long, so unless your soil is very loose, you will often lose the bottom part when you dig the plant On the other hand, if the weather or your time and strength don’t allow you to dig a bed in April, don’t worry. The roots will get down into the subsoil by themselves, drawing up valuable nutrients for you to eat in January and February.

If you also have plantain growing in your garden, it will be hard to distinguish the two at the seedling stage. The differences are that scorzonera leaves have serrated edges and are downy on the inner surface.

Skirret (Sium sisarum) Hardy

Skirret is best started from root divisions, but it will come from seed if you get it fresh. It’s a member of the carrot family, and the German name, Zuckerwurzel, seems to imply some sweetness. Reports are that you can store the roots in the ground over the winter, or in sand like carrots. The Siums as a whole are wetland plants and grow best in wet soil.

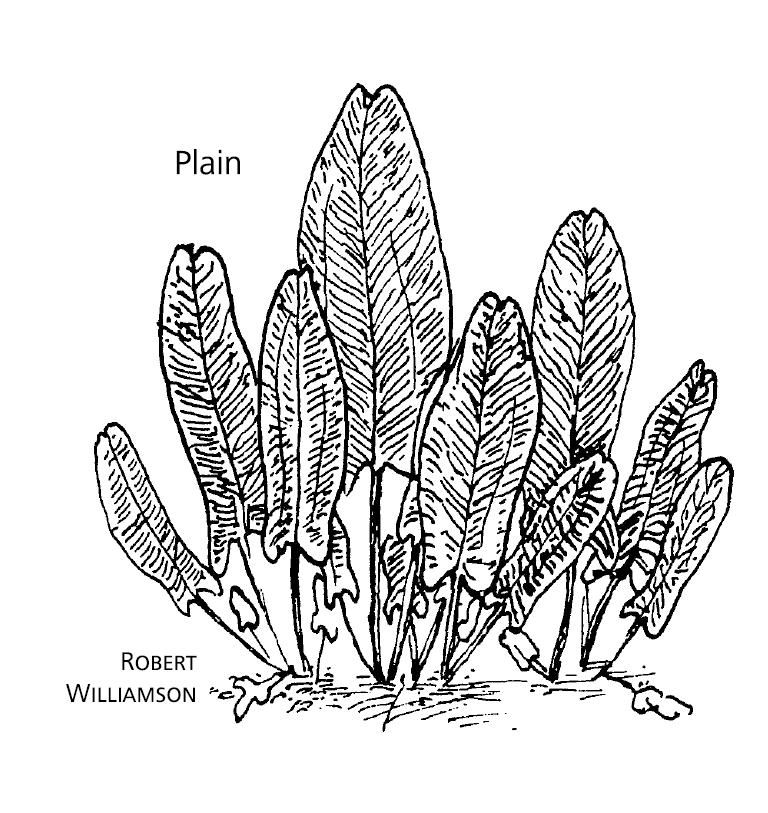

Spinach (Spinacea oleracea) Very hardy 0°F (–18°C)

Cold Resistant Savoy

Tyee (F1)

Giant Winter

Winter Bloomsdale

Spinach is amazingly hardy, but you have to provide rich soil with a fairly high pH and a well-drained bed for it to overwinter in. If sown in late July to mid-August, it will yield a fine fall crop as well as plenty of leaves till about Christmas. Then it rests until March (February in a mild winter) and comes on again. In cold sites, it’s best to cover plants from late November until the end of February if you want good production. In an early winter, you could cover it by late October. In northeaster country, a rug thrown over the frames will give added protection when the temperature goes below 15°F (–9°C). I've had it last to –2°F (–19°C) this way.