CHAPTER 6

Women at Work

Before the 1830s, nearly all women worked from home. They cooked and cleaned and cared for children. But in the nineteenth century, factories and mills began springing up in New England towns to turn cotton into cloth. Mill owners hired young women from nearby farms.

A bell woke the “mill girls” at four in the morning for a fourteen-hour day on the job. It was hard work, but there were some benefits. Young women could earn their own money and be more independent.

In 1844, female mill workers in Lowell, Massachusetts, formed one of the first US labor groups for women. They fought for better working conditions and a ten-hour workday.

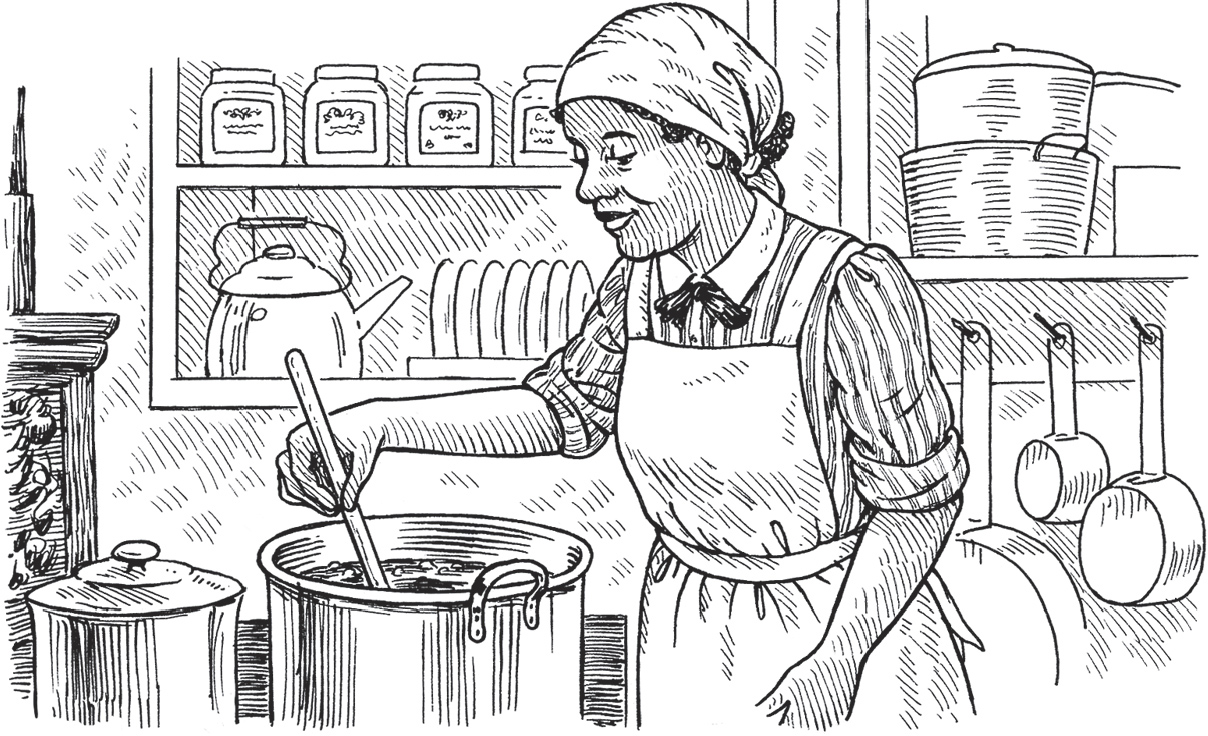

By the end of the century, women made up about 20 percent of the total workforce in the country. More African American women worked than white women. In 1900, about 43 percent of black women worked, compared to about 18 percent of white women. Many black women could not afford to stop working after they got married. In 1900, only 3 percent of married white women worked.

There were many reasons for this. African American women had fewer chances to go to school. They were forced to take low-paid, unskilled jobs such as cooks, servants, and seamstresses.

The nineteenth century was also a time of immigration. Twelve million immigrants arrived in New York City between 1880 and 1930. About 70 percent of foreign-born single women worked to help support their families.

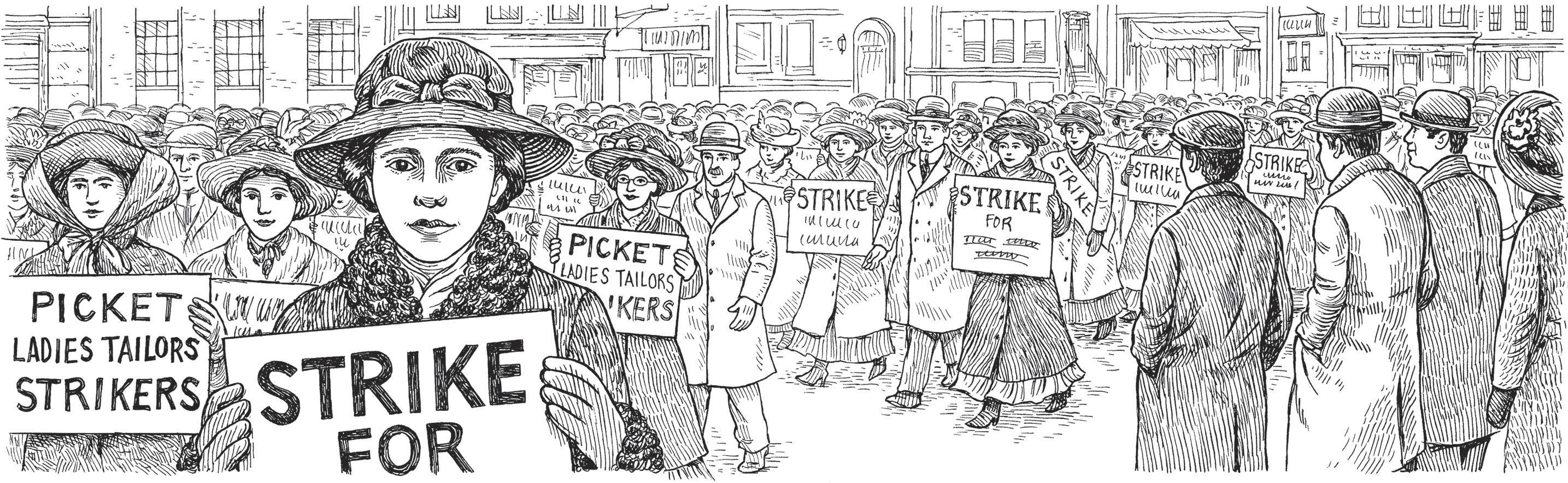

One was Pauline Newman, who was born in Lithuania in 1888. Schools there weren’t open to her. Why? She was Jewish. When her family moved to New York City, she began working at about age nine. Girls and women worked long hours for low pay in unsafe factories. Pauline wanted to help women improve their working conditions. In 1909, she helped organize thousands of women into the largest strike, or work stoppage, of American women to date. She continued fighting for fair treatment for employees as the first female organizer for the ILGWU (International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union).

Pauline had a long career bringing together women of all races and backgrounds. She believed they deserved a voice—and a vote—in making their workplaces and communities better.

Jane Addams (1860–1935)