CHAPTER 9

Women in World War II

In December 1941, the United States entered War World II, and the lives of millions of American women were about to change. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt had said that, during World War II, American women would do all that was asked of them, and much, much more. She was right.

World War II (1939–1945)

Before World War II, women could only join the military as nurses. While no women were in combat in World War II, they were definitely part of the US armed forces. In May 1942, Congress established what became the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). During the war, about 150,000 women were WACs. They served as clerks, typists, and radio operators. They repaired trucks and drove vehicles.

About one hundred thousand women also joined the Navy as WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). In addition to secretarial jobs, WAVES worked as translators and in coding and decoding messages. They were also air traffic controllers and weather forecasters.

More than eleven hundred women pilots volunteered to ferry planes from factories to military bases. They were known as WASPS, which stood for Women Airforce Service Pilots. The women flew every type of army aircraft. They also tested repaired planes to determine whether they were safe to fly.

To win the war, America needed more ships, planes, tanks, trucks, ammunition, and equipment. According to the National WWII museum, more than twelve million Americans served in the military. With so many men in uniform, who would work in the shipyards, plants, and factories?

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson had a solution. Empty jobs would be filled by “the vast reserve of woman power.” Six and a half million women worked outside the home in World War II.

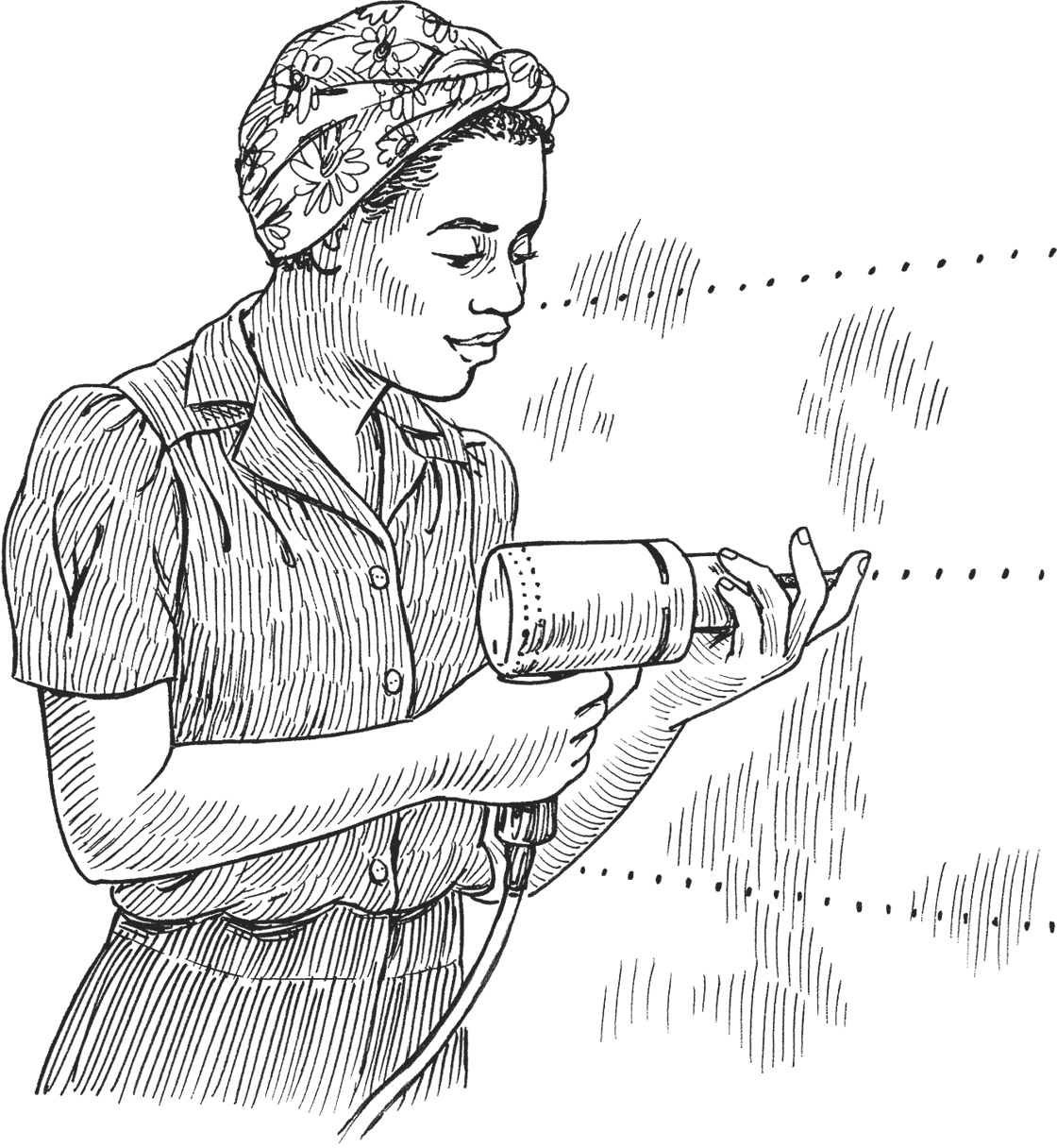

A poster and song celebrated a fictional character called Rosie the Riveter. Rosie was the symbol of American women’s patriotic spirit:

All the day long,

Whether rain or shine,

She’s a part of the assembly line.

She’s making history,

Working for victory,

Rosie the Riveter.

Women made uniforms and boots for soldiers. They worked in factories to make silk parachutes. Women produced ammunition on assembly lines. They welded ships and airplanes.

During the war years, the United States produced three hundred thousand aircraft, eighty-six thousand tanks, and twelve thousand ships, along with millions of guns—all of which couldn’t have happened without women. Women proved they could do jobs that until then had only been done by men. About half of American women held jobs outside the home during the war.

In some factories, day care centers helped young mothers work both day and night shifts. These centers were new to Americans. Between 1942 and 1945, the government funded more than three thousand childcare centers serving six hundred thousand children.

Good factory jobs enabled black women to leave domestic service. As many as six hundred thousand African American women joined the war effort. In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order banning race discrimination in any business related to defense and war production. But this was often ignored.

Though racism still existed in the workplace, Ruth S. Wilson, a black sheet-metal worker and mother, said, “World War II changed my life because I made more money and became independent.”

Like Ruth, millions of American women felt a new sense of independence during this time. They succeeded in new roles and occupations.

But when the war ended, millions of men returned to civilian life. Most people expected life to return to “normal.” And often, especially for white middle-class families, that meant men went to work while women stayed home as wives and mothers. Throughout the 1950s, if they did work, nearly all women took traditional female jobs, becoming secretaries, waitresses, teachers, or nurses.

But would women settle for the way things used to be?

Maya Angelou (1928–2014)