CHAPTER 10

The Second Wave

After World War II, there was an economic boom in the United States. Soldiers and sailors came home to attend college and take jobs. They married, bought homes, and started families, leading to a big generation of children called “the baby boomers.”

The ideal woman of the 1950s was no longer Rosie the Riveter but a homemaker devoted to her husband and children. New processed foods like sliced cheese and frozen meals saved her time in the kitchen. Women had dishwashers, vacuums, and other appliances to make cleaning easier.

In 1950, only about 29 percent of women worked outside the home. More single women worked than those who were married. As before, higher percentages of black women, whether single or married, were in the workforce. But all working women shared something: They were paid less than men.

Betty Friedan

The government-sponsored childcare of the war years had ended. Married women had an especially hard time combining work and family. That was true for a woman named Betty Friedan. Betty had grown up in a Jewish family in Illinois. Born in 1921, she graduated from Smith College (another Seven Sisters school) in 1942. Then she got a job as a journalist. But when she became pregnant with her second child, she was fired.

Betty began writing from home, selling articles to magazines. After returning to Smith College for her fifteenth class reunion, she began asking her former classmates some questions about their lives. She found that many had comfortable lives but were unhappy. She said, “American women were frustrated in just the role of housewife.”

Women wanted more freedom to choose their paths in life. They wanted families and careers. No one had been talking about this publicly. Betty called what women were feeling: “The Problem That Has No Name.” In 1963, she turned her ideas into a best-selling book called The Feminine Mystique.

Betty received a flood of letters from readers. She said, “I realized that it was not enough just to write a book. There had to be social change.”

So in 1966, she cofounded the National Organization for Women (NOW). It launched the “second wave” of the women’s rights movement. Like the movement of the nineteenth century, it mostly was driven by white, middle-class, well-educated women. Many of them (and some men, too) began to think of themselves as feminists—people who believe in the equality of the sexes in all aspects of life—public and personal. They wanted to be able to plan their families, and have the chance to pursue careers to become lawyers, surgeons, professors, and scientists.

Alice Walker

Black feminists also became active at this time. Many African American women felt that neither the women’s rights movement nor the civil rights movement addressed important issues that mattered to the experiences of women of color.

Some black feminists at this time included author Angela Davis, who wrote about women, race, and class. Novelist Alice Walker became a leader in exploring the impact of racism and culture on black women. In 1972, lawyer Florynce “Flo” Kennedy helped nominate New York Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm to run for president. Chisholm was the first black woman elected to Congress and also the first African American woman to run for president.

Shirley Chisholm

In the early 1970s, Gloria Steinem was called “the face of feminism” and a trailblazer of the second wave of the women’s movement. She was born in 1934 in Ohio. Like Betty Friedan, she attended Smith College and worked as a journalist. As an editor of New York magazine, she published the first stand-alone issue of Ms. magazine in January 1972. Its feminist motto is “More than a Magazine, A Movement.”

Gloria also helped start the National Women’s Political Caucus, which works to increase women’s participation in politics and provide support for women running for office. In 2017, at age eighty-three, Gloria was still giving speeches.

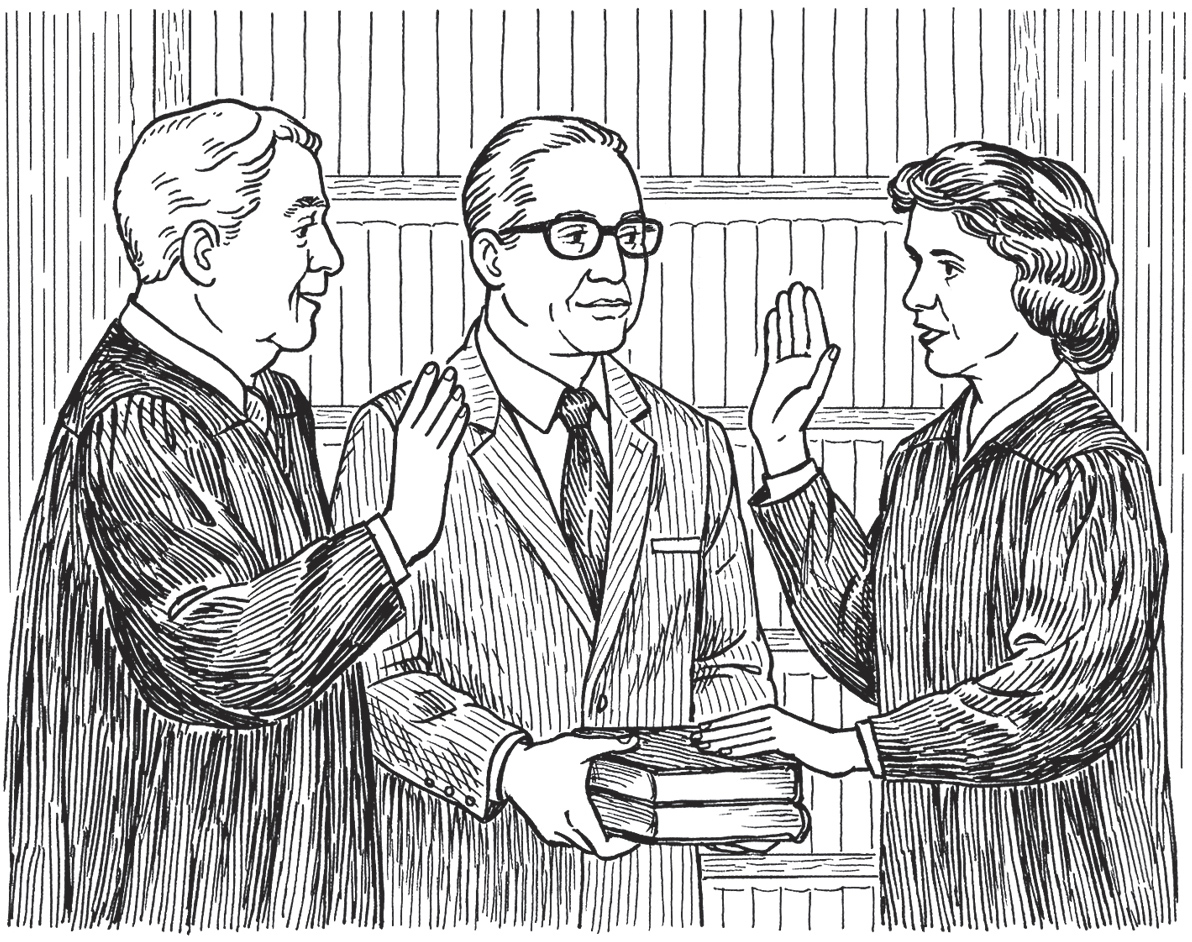

The second wave of feminism helped bring about many changes in society. Many barriers for women were broken. In 1981, Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman to serve as a judge on the Supreme Court. (In 2017, three of the nine judges were women.) Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman to run for vice president on a major party ticket in 1984. In 2007, Nancy Pelosi became the first female Speaker of the House of Representatives in Washington, DC. In 1997, Madeleine Albright became the first woman secretary of state. (By 2009, two other women—Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton—had also held this job.)

In an interview in 1992, when she was seventy-one, Betty Friedan reflected, “The women’s movement is an absolute part of society now.” Betty died on February 4, 2006, her eighty-fifth birthday.