It was now that the slaves began to desert to us, and by their local knowledge we were afterwards enabled to carry on a system of harassing warfare which, in the end, obliged the inhabitants to throw themselves upon our mercy, instead of the protection of their militiamen.

—LIEUTENANT JAMES SCOTT, MAY 18131

IN JULY 1807 a fourteen-year-old slave named Willis fled from his master in Princess Anne County by stealing a boat and rowing out to a British warship anchored in nearby Lynnhaven Bay. Willis expected a warm welcome, for war seemed imminent after the recent British attack on the USS Chesapeake. Initially, the British took in, fed, and clothed Willis and four other fugitives, but in early August the Royal Navy Commodore sent them back to their masters in a bid to defuse tensions with the Virginians. Instead of dwelling on that betrayal, Willis later recalled that “he had been to the British once & that they treated him well & he wished his master had let him remain.” In 1814, Willis escaped again to a British ship along with “many other negroes in the neighbourhood.”2

Willis’s persistence demonstrated the allure of the British as potential liberators among the restive slaves of the Tidewater. In March 1813 in Mathews County, the slaves who broke into John Ripley’s store called themselves “Englishmen.” In July 1814 in Calvert County, Maryland, a white farmer sought water by visiting a spring. Noting the slaves gathered there, he hid behind a tree and overheard “the negroes belonging to the said John J. Brooke huzzaing for the different British admirals.” Two days later, three of those cheering slaves fled to the warships. A later Chesapeake slave, Frederick Douglass, recalled looking longingly at sailing ships scudding along the bay as “freedom’s swift-winged angels” and vowing, “This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom.” Willis had felt the same way.3

By their enthusiasm for the British as liberators, the Chesapeake slaves made it so, flocking to them in unanticipated numbers that would compel a major rethinking of British strategy. At the start of their first Chesapeake campaign in 1813, the British officers were reluctant to take on more than a few black men as pilots and guides. During their second campaign in 1814, the British would seek and welcome hundreds of runaways, including women and children. Willis and other runaways would not take no for an answer.

Admirals

During 1812 the British proved slow in mustering their naval might against the Americans. Committed to a massive conflict against the mighty Napoléon, the Royal Navy was stretched thin around the globe. To command the undermanned North American squadron, based at Halifax, the Admiralty assigned Vice Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, who was better known for his lavish style of life than for his devotion to active service. Thomas Grenville of the Admiralty considered Warren “good for nothing but fine weather and easy sailing.” But Warren had some experience as a diplomat, and the imperial government empowered him to negotiate peace with the Americans. Keen to concentrate on fighting the French, the British wanted promptly to stop the distracting American war. In June, the empire suspended the Orders in Council, which had restricted American trade with Europe, hoping thereby to mollify the Americans enough to restore peace. Instead, they continued to fight to break up the British alliance with Indians and to seek an end to the impressment of sailors.4 In sum, Warren held two conflicting assignments: as a diplomat charged with seeking peace and as an admiral obliged to inflict the pain of war.

The Admiralty expected too much from Warren, who had too few warships to blockade the long American coast and protect the vulnerable British trade with the West Indies against American privateers. Warren’s squadron also suffered from a shortage of skilled seamen, which reflected the strain of a prolonged global war on the limited manpower of Great Britain. His standing with his superiors in the Admiralty eroded when some of the powerful American frigates slipped out to sea, where they captured or destroyed three British frigates. Used to defeating the French and Spanish, no matter the odds, the British felt shocked at their losses to the Americans. The defeats threatened British morale far beyond their paltry strategic significance. Rather than take the blame, the Admiralty heaped it on Warren.5

In December 1812 the British leaders decided to escalate the war against the Americans, to punish them for rejecting a quick peace. Napoléon’s recent crushing defeats in Russia also persuaded the imperial government that it could afford to divert additional ships and men from Europe to fight the Americans. By the summer of 1813 the Royal Navy had doubled the number of warships in American waters to 129: five times the strength of the American navy. The Admiralty directed Warren to take his warships into Chesapeake Bay to smite Maryland and Virginia, deemed the heart of American resources and the political base for the pro-war Republicans. By blockading trade capturing merchant ships and privateers and by raiding farms and villages, the British hoped to compel the Americans to pull back their troops invading Canada to defend the Chesapeake country instead. After a year’s restraint, the British meant to teach the Americans a bloody, burning lesson: that they should never provoke the empire.6

To promote greater aggression, the Admiralty sent Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn to serve as Warren’s second-in-command. Forty years old, Cockburn was in the prime of his health and nautical career, in contrast to Warren, who had seen his best days. As the son of a wealthy merchant, Cockburn had learned the self-righteous values of self-discipline and hard work, which distinguished his character from the aristocratic Warren. Cockburn entered the Royal Navy as a teenage midshipman. Zealous, able, and courageous, he won the esteem of his superiors, particularly Britain’s greatest admiral, Lord Horatio Nelson, who became his patron. In 1795, at the precocious age of twenty-three, Cockburn took command of a frigate posted in the Mediterranean. In later operations along the Dutch coast, Cockburn developed an expertise in amphibious operations, experience which subsequently served him well in the Chesapeake.7

Supremely self-confident, he was a flamboyant performer of command who delighted in military pageantry. Another officer described Cockburn as “very fond of Parade & shew, 60 men therefore to parade every morning” with “the Band playing ‘God Save the King.’” A great wit and remarkably calm under fire, he inculcated an esprit among his subordinate officers, who found his dash and activity contagious. Cockburn also encouraged and promoted talented young officers, who became deeply devoted to their patron. One midshipman fondly recalled “that undaunted seaman, Rear-Admiral George Cockburn, with his sun-burned visage, and his rusty gold-laced hat—an officer who never spared himself, either night or day, but shared on every occasion, the same toil, danger, and privation” as the petty officers.8

Devoted to his king and empire, Cockburn disdained the Americans, for indirectly helping the French and for harboring British deserters. He shared the contempt of all British officers for the American declaration of war as cowardly and treacherous because made at a critical moment in the empire’s desperate struggle against Napoléon. One officer complained that the Americans “snarled at us like curs, when a bull is being baited; for while we were tossing the [French] dogs in front, they took the opportunity of biting our heels.” The British officers longed to punish the Americans for their temerity. Once humbled by defeat, surely they would reject the Republicans, restore the Federalists to power, and accept British leadership in commerce and diplomacy.9

Raids

While ravaging the Chesapeake shores and shipping, admirals Cockburn and Warren were supposed to avoid great risks, for the empire could ill afford any losses of men or ships. Instead of mounting mass assaults on strongly fortified positions, the admirals were supposed to make smaller and safer raids on poorly defended places. British leaders remembered the catastrophic defeats on land that had cost them Burgoyne’s and Cornwallis’s armies during the last unhappy war in America. To avoid repeating the humiliations of the American Revolution, the British avoided major battles and probes deep inland where their precious men might get ambushed in the woods, picked off by riflemen, and surrounded by superior numbers. One officer concluded, “To penetrate up the country amidst pathless forests and boundless deserts, and to aim at permanent conquest is out of the question.” The British came to harass rather than to conquer America.10

The British perceived the vast American landscape as an unconquerable foe. Coming from a mild, rainy, compact, and cultivated island, they felt awed by the bigger, wilder land and volatile climate of the Chesapeake. “Low, flat, sandy banks covered with pines is all we see,” Rear Admiral Edward Codrington reported from his warship. The naval officers regarded the riverside farms and plantations as pleasant oases in the midst of “the boundless forests” of massive trees that stretched around and behind them. And the British suffered from the blistering summer sun and clouds of mosquitoes. Lieutenant James Scott recalled faces “bloated, swelled, and disfigured by the smarting, itching incisions of . . . these bloodthirsty devils. The heat was suffocating.” And the sudden, violent storms of summer sometimes capsized barges and smaller warships. After one storm of thunder, rain, and wind, a naval captain reported, “we saw immense trees torn up by the roots, [and] barns blown down like the card houses of children.” Codrington concluded, “This Chesapeake is like a new world.” It was a strange and frightful new world for men of the sea from a distant island.11

Rather than invade the daunting land, the British usually kept close to the security of their warships during the campaign of 1813. Cockburn insisted that the Americans’ “Rifles & the thickness of their Woods . . . constitute their principal, if not their only, Strength.” When the British did venture inland, their operations often went badly awry owing to faulty information. “We have [a] nasty sort of fighting here amongst creeks and bushes, and lose men without show. . . . It is an inglorious warfare,” lamented a British officer. In August, Sir Sidney Beckwith sadly reported that his troops became confused when fired upon while “moving thro’ the thick wood” about four miles from the bay. After his spooked men shot three of their own by mistake, Beckwith decried “the extreme imprudence of risking such Troops” in the American woods. A Tidewater man happily noted, “The enemy does not like to put his feet on our shores, as many parts thereof are covered with pine & they know not what force we may have.”12

Instead, the admirals exploited the superior mobility of their ships to mount hit-and-run raids before the land-bound American militia respond in force. To maximize impact and minimize risk, the warships roamed up and down the bay, alarming all shores and making, in Warren’s words, “sudden & secret attacks at those points in which the Enemy is most vulnerable.” The American secretary of the navy aptly attributed the British strategy to “our extensive and navigable waters and their great naval superiority.”13

By targeting shipping and exposed villages, the British took many prizes while suffering few casualties. “Never was there a finer opportunity to make our fortunes,” one officer exulted. While the big ships of the line and frigates kept to the deeper waters in the middle of the bay, the shallower-draft sloops and schooners probed up the rivers, “searching out, capturing, and destroying every vessel or craft floating on the waters,” as Lieutenant Scott put it. The British burned the older ships but loaded the better ones with loot and sent them off to Bermuda and Halifax for sale, with the prize money divided among the capturing officers and crews.14

Barges filled with armed sailors and marines also landed to plunder exposed farms, plantations, and villages, but the British fled to their ships as soon as the local militia assembled in threatening numbers. In a game of cat and mouse, the British warships and barges would approach a point, attracting a concentration of alarmed militia, before sailing away to an unguarded point to raid. Scott exulted, “Our business was generally achieved before they could possibly reach us, from the circuitous track they were obliged to pursue. . . . The poor militiamen were fairly worried out of their lives, [for] they knew no repose by night or by day” as the British raiders “were here, and there, and everywhere.” One British officer aptly called the strategy a “species of milito-nautico-guerilla-plundering warfare.”15

Civil War

The dirty secret of the Chesapeake operation was that the Royal Navy depended on local help to sustain the blockade, for their crews needed fresh water and provisions from the farms and plantations along the shore. The British also relied on American pilots to guide them around the treacherous shoals and up the shallow rivers. In addition, the naval officers paid informants to reveal the strong and weak points of the American defenses. Deftly deploying flattery, trickery, and money, Cockburn cultivated suppliers, guides, pilots, and spies. He learned much simply by reading the American newspapers, which reported military deployments in surprising detail. A visitor noted that the admiral routinely received “newspapers, smoking from the press, and every other information they could obtain to our strength, dispositions of force, &c.”16

Many Americans readily sold their wares and principles for British gold. Loading their vessels with cattle, poultry, sheep, hogs, and vegetables, they sailed straight for British warships while flying a white flag. By Cockburn’s prearrangement, the British “captured” the ships, took off the cargo, but then generously paid the captains and released their ships to return home with a phony story. One canny captain damaged his sails, “to shew when he went home, that he had been fired at and compelled (sorely against his will!) to go along-side one of the enemy’s ships.” In another trick, the merchant captain hid a cargo of provisions beneath a load of lumber. After buying the food, Cockburn gave the obliging captain a pass to sail unmolested through the British fleet to another American port to sell the lumber, thereby making a double profit.17

On islands and exposed points where resistance was futile, the inhabitants sold livestock and provisions to the raiders. In April 1813 the British landed in force on Spesutie Island, Maryland, and threatened to burn homes. “This had the desired effect & we procured a prodigious quantity of everything,” Major Marmaduke Wybourn reported. In August on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, a militia commander complained that the illicit trade with the enemy “was so great, as to be highly criminal.”18

The British cooperated with the tender consciences and cunning evasions of their new friends, who wanted to keep secret their assistance to the enemy. A British officer explained, “The plan agreed on was this: they were to drive [their cattle] down to a certain point, where we were to land and take possession; for the inhabitants being all militiamen, and having too much patriotism to sell food to ‘King George’s men,’ they used to say, ‘put the money under such a stone or tree, pointing to it, and then we can pick it up, and say we found it.’” Sometimes the raiders left payment in a cupboard for the poultry or livestock of a cooperative farmer.19

The British suffered some stinting periods of short rations but in general, their squadron derived plenty to eat from the shores of the Chesapeake. Lieutenant Scott concluded, “Fish, flesh, and fowl were obtained in abundance on the Chesapeake station.” Warren exulted, “I never saw a country so vulnerable, open to attack, or that affords the means of support to an enemy’s force, as the [United] States.” In late 1813 the official newspaper of the Madison administration, the National Intelligencer, warned that the enemy could not be defeated “while we continue to feed his armies and fleet.” In pursuit of profits, many Americans supplied the national enemy.20

In addition to the slaves, the Americans faced another internal enemy: themselves. A Baltimore newspaper lamented, “Certainly no country was ever cursed with so many traitors as we have.” Because the American law of treason required at least two witnesses to an overt act of war, prosecutors failed to convict any of the accused suppliers of provisions and information to Cockburn. At best, officials could harass the suspected traitors with arrests and brief stints in jail pending trial.21

By driving up the costs of war and ruining those who resisted, the British hoped to promote political divisions and perhaps even a civil war within the United States. Warren predicted, “It is possible that the increasing Demands for cash & consequently Taxes may occasion convulsion & Disorder among the several States.” He reasoned that Americans had to learn harsh lessons before they would renounce their unjust war and oust their bumbling Republican leaders, embracing instead the pro-British Federalists. Another officer explained that the Americans needed to “experience the real handicaps and miseries of warfare. . . . So it is with democracy at war. Burn their houses, plunder their property, block up their harbours, and destroy their shipping,” then but only then “you will be stopped by entreaties for peace.”22

Although waged by distinct governments, the War of 1812 was also a civil war between kindred people sharing the same language and cultural heritage. Indeed, combatants often struggled to tell friend from foe. A British officer of marines recalled that during night attacks on the Chesapeake shores, the British sailors had to wear “white bands round their arms & hats, to distinguish English from Americans.”23

Americans and Britons waged the war with familiar words as well as with weapons. Appealing to similar values of freedom and Christianity, the two sides employed persuasion to weaken their enemy by making converts. Admiral Warren complained that American captors politically seduced their British prisoners: “every art [is] practiced to persuade them to become American Citizens, which, from the peculiar situation of the two Countries speaking the same Language is more easy to accomplish than in any other part of the world.” While the Americans enticed deserters from the Royal Navy, the British worked to divide the Americans by rewarding Federalists and punishing the Republicans. British sailors could become Americans by deserting; Federalists could become British allies by supplying the blockading ships.24

Both sides regarded the war as a second act in a drama launched by the American Revolution. During the new war, some British officers called the Americans “rebels,” as if they had not truly won their independence and the revolution was not yet lost to the empire. Because of the cultural overlap between Americans and Britons, similar people fought on both sides. British immigrants lived throughout the United States, and British forces included many sons of the Loyalist refugees from the revolution. “It is quite shocking to have men who speak our own language brought in wounded; one feels as if they were English peasants, and that we are killing our own people,” declared one British officer posted in the Chesapeake. He added, “There are numbers of officers, of the navy in particular, whose families are American, and their fathers in one or two instances are absolutely living in the very towns we are trying to burn.” For example, the British general Sir Sidney Beckwith had cousins in Virginia.25

Although a fierce supporter of the war, St. George Tucker had relatives from Bermuda holding high commands in the British military. His nephew John G. P. Tucker became a colonel in the British army and fought against the Americans on the Niagara front. During the war, Colonel Tucker wrote to his uncle, “Altho we are politically the most determined Enemies, yet our private feelings can never cease to impel us to acts of friendship & kindness” provided they did not contradict “the first duty which we owe to our Country.” He signed, “Your affectionate nephew.” Another Tucker nephew commanded HMS Cherub, which helped to capture a powerful American frigate, but he suffered severe wounds in the battle. St. George Tucker and his brother Thomas felt tormented by the tension between their intense family ties and their equally fervid patriotism. Thomas consoled St. George: “How lamentable, how distressing, my beloved brother, that friends so truly dear to us shou’d be engaged in the service of the enemy. I have always depreciated the consequences of a war in which the nearest & dearest relatives are engaged on opposite sides, & liable to become the murderers of each other.”26

Irish-born Americans particularly experienced the conflict as a civil war. Although they had immigrated to the United States to escape British rule, the Irish faced impressment when found on board American merchant ships. Worse still, once the war began, British officers threatened to hang as traitors any former subjects captured bearing arms against their king. British officers perceived the American navy as filled with “traitors to their country [who] were supposed to be more than half the force opposed to us”—in the words of Major Wybourn. In sum, the British officers treated Irish Americans as rebels in a civil war between the empire of their birth and the republic of their choice.27

A naturalized American citizen, John O’Neill hated the British as “the oppressors of the human race, and particularly of my native country, Ireland.” O’Neill fought fiercely to defend his home on May 3, 1813, when the British raided Havre de Grace, Maryland. The rest of the local militia quickly fled, leaving O’Neill alone to resist 150 Britons until they wounded and captured him. After burning his house, the victors threatened to hang O’Neill as a traitor, although he had resided in the United States for fifteen years. Three days later the British relented, releasing him on parole rather than make a popular martyr of a respectable man. Admiral Warren subsequently (and implausibly) insisted, “I was not informed of this man being an Irishman, or he would certainly have been detained, to account to his sovereign and country for being in arms against the British colors.” Warren could not admit that he had compromised his empire’s policy of punishing any former subject captured in the enemy’s service.28

The conflict also verged on a civil war within America because of the bitter partisanship pitting Federalists against Republicans. Each party denounced the other as betraying the republic to assist a foreign enemy. Republicans cast the Federalists as latter-day Tories who served the British, while the Federalists denounced the Republicans as stooges for the French dictator. By frustrating the war effort, the Federalists sought to expose the Republicans as fools for declaring war. By winning the war, the Republicans hoped to discredit the Federalists and cast them into political oblivion. The Baltimore American explained that in time of war “there are but two parties, Citizen Soldiers and Enemies—Americans and Tories.” Recalling the revolution’s brutal suppression of the Loyalists, Thomas Jefferson boasted that Republican mobs would silence the Federalists. In Norfolk, a mob fulfilled Jefferson’s prophecy by tarring and feathering a Federalist before dumping him in a creek.29

The Conspiracy Against Baltimore, or the War Dance at Montgomery Court House. Crafted in 1812 by an unknown Maryland Republican, the cartoon lampoons the state’s Federalists including the newspaper editor and publisher Alexander Contee Hanson, Jr. depicted with the devil’s horns at center. He looms over Robert Goodloe Harper shown playing a harp, as a pun. In the group to the left, the dancing man with a distinctive hat, a military chapeau de bras, is General Henry Lee, a former governor of Virginia, who suffered crippling wounds in the Baltimore riot. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society).

The partisan fury peaked in Baltimore, a booming seaport of 41,000 people, most of them Republicans. In late June, Republican mobs tore down the Federalist newspaper office of Alexander Contee Hanson Jr., dismantled ships suspected of trading with the enemy, and destroyed the homes of free blacks accused of British sympathies. A defiant Hanson fortified a new office with armed guards, including the former revolutionary war generals James Lingan and Henry Lee (also a past governor of Virginia). In late July, the Federalists fired into an attacking mob of enraged Republicans, killing one and wounding others. The city magistrates jailed the Federalists, but the rioters broke in the next day to batter their foes. Watching women cried, “Kill the tories!” and the rioters sang:

We’ll feather and tar ev’ry d[amne]d British tory,

And that is the way for American glory.

Stabbed in the chest, Lingan died. Eleven others, including Lee and Hanson, suffered crippling injuries. A few token prosecutions convicted only one rioter, and he merely paid a small fine. A juror explained “that the affray originated with them tories, and that they all ought to have been killed, and that he would rather starve than find a verdict of guilty against any of the rioters.”30

Pride

British naval officers considered pride the worst of American sins. Adhering to a hierarchical code of strict discipline, the officers disdained the pushy and boastful Americans, who seemed to recognize no superior. When compelled to postpone an attack, Warren lamented that “any Delay on our side in attacking them has only added to their pride & presumption”: a most distasteful development. But Lieutenant Scott warned the Americans that “severer trials awaited their pride.” Rather than simply defeat the Americans, the officers longed to humble them.31

By ravaging the Chesapeake shores, Cockburn hoped to disgrace the Americans and discredit their republic. In March 1813 he assured Warren that “the whole of the Shores and Towns within this Vast Bay, not excepting the Capital itself will be wholly at your mercy, and subject, if not to be permanently occupied, certainly to be successively insulted or destroyed at your Pleasure.” The British raids would, Lieutenant Scott explained, expose the inability of the Madison administration “to afford the necessary degree of protection, justly expected by the inhabitants of every country whose government ventures to decide upon a state of warfare.” After plundering one Virginia farm, a witty officer left a note written in sheep’s blood to pledge that President Madison would pay the owner for the stolen livestock taken “for the use of the British navy.”32

British officers detested most Americans as greedy cheats, long on cunning but short on scruples. “They will do anything for money,” a captain concluded. According to Rear Admiral Codrington, after the British occupied an American town, a resident boasted, “I’m as brave as Julius Caesar” and “I’ve as fine a house in this city, and shan’t quit it for you or anybody.” A British officer replied, “Oh, ho! You’ve a fine house here have you? Well, I’ll soon rid you of that encumbrance, for I’ll burn it directly.” Falling to his knees, the American “rascal” begged, “Mister if you won’t burn my house, I’ll do what ever you please.” Codrington concluded, “This is the picture of the people in general. They are meanly inquisitive, arrogantly impertinent & cruelly tyrannical where their power is uncontrouled, and yet they bend the neck to the yoke of coercion as if nature formed them for slaves.”33

Hardened by war and proud of their discipline, the British officers mocked the Americans as dishonorable amateurs full of false bravado and real cowardice. Major Wybourn dismissed the United States as “a country of Infants in War.” Used to fighting in the open, the British disdained the American preference for long-distance sniping from behind cover as cowardly and effeminate. In one battle report, Cockburn derided his foes: “no longer feeling themselves equal to a manly and open Resistance, they commenced a teasing and irritating fire from behind their Houses, Walls, Trees, &c.” The British denounced as cheating the expedients of untrained and poorly equipped American militiamen. A British officer declared, “They fight unfairly, firing jagged pieces of iron and every sort of devilment—nails, broken pokers, old locks of guns, gun-barrels—everything that will do mischief.”34

The Americans especially infuriated the British by deploying floating, explosive mines, known as “torpedoes,” cast adrift to strike and destroy warships in the night. Although the torpedoes proved ineffective, they offended the British as cowardly and treacherous. Citing the “dastardly” torpedoes, the British felt justified in conducting their punishing and plundering war against the American coast.35

Republicans denounced Cockburn as an indiscriminate plunderer, and some historians have mistaken his strategy as “total war.” In fact, he was highly discriminating in his targets, for Cockburn sought to teach Americans the perils of their pride, and as a paternal teacher he had to reward the deserving as well as punish the stubborn. Cockburn carefully investigated the political allegiances of the leading men dwelling along the shore, for he meant to harass Republicans and spare Federalists. A visitor to Cockburn’s flagship returned to report that the admiral “appears well informed of the political character of many persons and places on the shores of the bay.” In one raid on a Maryland town, Major Wybourn told a woman, “the question they generally asked when they went to any place was, how they voted at the elections, and inquired . . . if her uncle, meaning Mr. Henderson, voted for the war.” Apparently he had voted Republican, for Wybourn had Henderson’s stable and coaches burned. In general, Cockburn’s men plundered and destroyed the buildings of anyone who resisted (usually Republicans) but protected the property of those who submitted.36

In mid-April 1813, Cockburn sailed up Chesapeake Bay to “teach a salutary lesson” to his American students on the shores of Maryland. On April 27 his men raided Frenchtown, near the head of the bay. A brief militia resistance exposed the town’s storehouses to looting and burning, but Cockburn spared the private homes. Turning west, he attacked Havre de Grace after noticing a new battery, whose crew “hoisted the American colours, by way of bravado.” Determined to humble every display of American pride, Cockburn led an assault on May 3. A brief and futile resistance by a few militiamen (including John O’Neill) qualified the village for a thorough plundering (and some burning) of homes as well as stores. Cockburn explained that he sought to bring the people “to understand and feel what they were liable to bring upon themselves by building Batteries and acting towards us with so much useless Rancor.”37

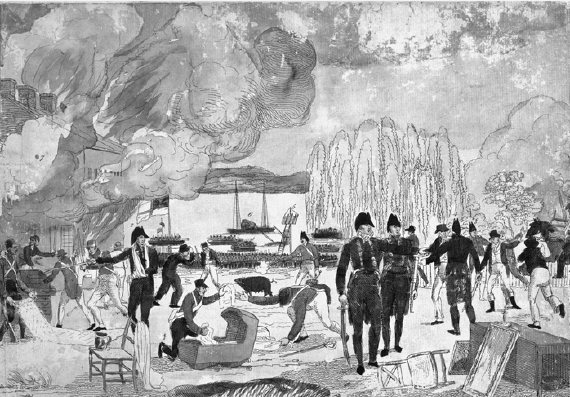

Admiral Cockburn Burning & Plundering Havre de Grace on the 1st of June 1813; done from a Sketch taken on the spot at the time. At the right of center Cockburn leans on his sword while his marines and sailors loot the village. Note the British barges in the background. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society)

Turning east, Cockburn attacked Fredericktown and Georgetown, along the Sassafras River of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. On May 6, Cockburn warned that if the inhabitants “offered any useless or irritating opposition, they must expect the same fate as that which had befallen Havre [de Grace] and Frenchtown; but if they yielded, private property would be respected, the vessels and public property alone seized, and that whatever supplies might be required would be punctually paid for.” The local magistrates wanted to submit, but a fiery militia officer ordered his men to shoot at the British landing party. After routing the militia, the British plundered and burned both towns, sparing only a few houses with especially charming women or with owners who paid a ransom in cattle. A local Federalist blamed the “imprudent & foolish conduct” of the Republican militiamen who fired a few shots and then ran away, exposing the abandoned villages to the raiders.38

Preferring discretion to valor, the people of nearby Charlestown surrendered rather than risk their homes. To prevent militia resistance, the town fathers “buried their cannon & knocked down a little fort,” as a relieved Federalist reported. Lieutenant Scott concluded that the British had opened “the eyes of the whole neighborhood . . . to the folly of irritating resistance.”39

Cockburn played the benign protector when Americans submitted. Later that month a British frigate ran aground near Annapolis, but the militia wisely declined to open fire. Sending a message ashore, Cockburn assured the inhabitants that their “prudence . . . in not firing on the frigate which grounded near their city saved it from destruction.” Similarly, on Kent Island in August, Cockburn compensated the passive inhabitants for some thefts made by rowdy sailors, whom the admiral had flogged. And, “from Motives of Humanity,” he protected a shipment of coal bound by merchant ship from Virginia to New York “for the use of the New York Hospital.”40

On his flagship, HMS Albion, Cockburn delighted in hosting genteel and cooperative Americans. A guest gushed to a newspaper that he had been “treated with great politeness and attention by the commander, Ad[miral] Cockburn, who unites the gentleman with the seaman.” Cockburn entertained grandly, for another visitor recalled “every eating & drinking Vessel was of Silver. The Table lighted by 8 silver Candlesticks which reflected from large Mirrors around his Cabin, made the Scene quite dazzling.” Major Wybourn recalled that Cockburn hosted a “large party of Americans who had been civil to our boats on the Maryland shore.” The officers “shewed them great attention, so much so that after a superb supper they began to find we were nearly all alike, for they had been told strange stories of us; we made them all completely drunk except one Methodist & . . . after breakfast they went on shore highly delighted.”41

Cockburn and his officers played the gallant with the women in captured villages and ships. After reporting the sack of Frenchtown, a Baltimore newspaper conceded, “It is justice to the enemy to say, they treated the women and children with considerable attention and respect.” At Havre de Grace, a sailor robbed a milliner of her dresses but was, in Lieutenant Scott’s words, “deservedly mortified by the Rear-admiral obliging him to return the spoils . . . to the forlorn damsel, with an impressive rebuke.” At Charlestown, Major Wybourn reported finding “a train of boarding school misses with governesses & teachers, about 40. These we shewed great humanity to & spared a village on their account.”42

Britons claimed to be truer men than the cowardly Americans who had failed to protect their families. On the Eastern Shore, Cockburn’s raiders surprised a genteel house “full of joyous girls” celebrating a birthday. Initially terrified, the girls soon felt reassured, Scott wrote, by the “courtly demeanour of the Admiral, and [his] promises of protection restored the roses to their smiling countenances, and they learned that the enemy and the gentleman may be combined.” Scott added, “Every male biped of the household stole off on the first intimation of our arrival, and left the fascinating innocents completely at our mercy.” British officers won a delicious victory every time they obliged American women to praise their humanity and to rue the cowardice of their own men.43

Villain

In June, Warren and Cockburn received reinforcements from Europe: 2,650 soldiers and marines. But they were a motley crew of men deemed expendable from serving with the British army in Spain. At the bottom of the barrel were 300 captured Europeans, mostly French, who agreed to serve the British in America rather than linger in confinement.44

The admirals thought that they had enough men to attack Norfolk’s first line of defense at Craney Island, where the Americans had built a battery and posted their gunboats. On June 22, Cockburn and Warren sent fifty barges laden with troops to land on the muddy island to overwhelm the battery, but the American fire smashed at least two barges and drove the rest away. Suffering heavy casualties, the British accused the Americans of massacring some helpless men. Then Admiral Cockburn and General Sir Sidney Beckwith squabbled over who was to blame. A pox on both, concluded Sir Charles Napier: “Cockburn thinks himself a Wellington, and Beckwith is sure the navy never produced such an admiral as himself—between them we got beaten at Craney.” For once, Cockburn’s impetuous, attacking style had failed, producing casualties that the British could ill afford to replace.45

Embarrassed by defeat and angered by the supposed massacre, the British sought a quick and easy victory on a more vulnerable American position at nearby Hampton. At dawn on June 25, the warships bombarded the shore batteries, while barges landed about 900 troops to the west. Fearing capture, the 500 defenders broke and ran into the woods and on to Yorktown, defying their commander’s orders to stand and fight. In their haste to escape, they threw away knapsacks, canteens, tents, and guns.46

The French mercenaries in the British force vented their anger and lust on the hapless civilians who remained in Hampton. Defying their own frightened officers, the mercenaries looted homes, committed a few rapes, and killed one sick old man (named Kirby) in his bed. Then at least thirty mercenaries deserted to join the Americans. The number of rapes remained murky because, one magistrate reported, “women will not publish what they consider their own shame; and the men in Town were carefully watched and guarded.”47

The Virginians converted their small military defeat into a major propaganda victory. In lurid prose, they exaggerated the atrocities and blamed them on the British commanders. In the most provocative version, Governor Barbour announced “that many of the Females had been violated in the most Brutal manner, not only by the troops, but in some instances by the Slaves that had joined them.” A negative fantasy tempting to Virginians, the raping slaves had no basis in evidence from Hampton.48

By dwelling on the perils of women and the duty of men to seek revenge, the Virginians refuted the British claims to superior civility. The Richmond Enquirer exhorted, “Men of Virginia! Will you permit all this? Fathers and Brothers & Husbands, will you fold your Arms in Apathy and only curse your despoilers?” On the Fourth of July in Richmond, the Republicans offered a toast: “That barbarity, which has inspired one sex with terror, has only inflamed the courage of the other.” In the Chesapeake, the propaganda war pivoted on who could best claim to defend America’s women.49

Deeply embarrassed, the British commanders blamed the mercenaries and cited the alleged massacre at Craney Island as the trigger for their rage. Beckwith deemed them “a desperate Banditti, whom it is impossible to control.” Despite their shortage of troops, Beckwith and Warren shipped the mercenaries away to Halifax and then back to Europe. The commanders primarily acted to stem their rampant desertion rather than to punish them for their crimes. But the Virginians also lacked moral consistency, for they welcomed deserting mercenaries despite their atrocities at Hampton. Indeed, the Virginians preferred to blame the mess on the British commanders.50

The Republican press and politicians cast Cockburn as an arch-fiend who ravaged one and all. Describing the sack of Havre de Grace, one writer insisted, “Cockburn stood like Satan in his cloud, when he saw the blood of man from murdered Abel first crimson the earth, exulting at the damning deed, and treating the suppliant females with the rudest curses and most vile appellations—callous, insensible, hellish.” A second writer concluded “that there breathes not in any quarter of the globe a more savage monster.” A third declared, “He should be lashed naked through the world with whips of scorpions.” Some Americans renamed their chamber pots after Cockburn. In Virginia, an Irish American offered a $1,000 reward for Cockburn’s head and $500 for each of his ears. By casting the admiral as a monster, the Republicans denied that he could ever teach them lessons by discriminating in his targets.51

Cockburn felt both amused and outraged by his American reputation. In December he thanked a subordinate for sending him an American pamphlet: “The Book against me which you sent has afforded some amusement to those who have had time to read it & Sir John Warren is now going through it.” The abuse increased Cockburn’s determination to teach more lessons to the Americans. Employing the then-common British name for them as “Jonathans,” Cockburn explained, “My Ideas of managing Jonathan, is by never giving way to him, in spite of his bullying and abuse.”52

In general, the British sought to minimize civilian casualties while seeking out property for destruction. Farms and plantations and villages burned, but the Chesapeake campaign lacked the bloody massacres of civilians and prisoners that characterized the war raging in Europe. Compared to the brutality of the Napoleonic wars, particularly in Spain, the Chesapeake campaign of 1813 was remarkable for claiming the life of only one captured civilian: Mr. Kirby. The only confirmed rapes also occurred at Hampton.53

In July 1813, after plundering and wrecking Hampton for ten days, the British withdrew to their warships and reverted to sailing up and down the bay to harass weak points in both Virginia and Maryland. In late August, Warren sailed away to Halifax with half the squadron and all the soldiers to save them from desertion and malaria, which peaked in late summer. A month later, Cockburn withdrew most of the rest of the squadron to Bermuda to refit through the winter. The admirals left behind Captain Robert Barrie with a rump force: one ship of the line, two frigates, and five smaller vessels. Barrie’s little squadron guarded the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, attacking the merchant ships and privateers that tried to exit or enter. Through the cold, stormy fall and winter, Barrie and his men kept up this hard duty, capturing or destroying eighty-nine ships by February 4, 1814.54

Barrie also harassed the Virginia shores with petty raids. On September 21, he landed seventy marines and eighty armed sailors on the shore of Lynnhaven Bay, to attack an American observation post at the Pleasure House: a popular bayside tavern before the war. Most of the militiamen fled, but Barrie captured nine and then burned the compound. He dared not pursue the fleeing militia because, he explained, “we were extremely ignorant of the nature of the Country . . . interspersed by Swamps and Thickets”: a common British lament in 1813. He assured Cockburn that the fall raids were “a sad annoyance to the Militia as the weather is very severe and the Troops are all sickly.” He delighted in reports that the militiamen “complain bitterly of being kept to such hard duty in harvest time.” Cockburn congratulated Barrie for “keeping my Yankee Friends on the Fret. We ought not to allow them any Peace or Comfort.”55

Despite the miseries inflicted on the Americans, the close of the campaign left the British frustrated with their opening foray in the Chesapeake. Despite capturing many merchant ships and damaging some villages, the British had failed to inflict a crippling blow that would compel the Madison administration to call off the invasion of Canada and sue for peace. Used to victory and proud of their gentility, the British officers also felt embarrassed by their defeat at Craney Island and by the atrocities at Hampton.56

But the British officers expected greater victories in 1814 thanks to the local knowledge gained in 1813. They had mastered the bay by making maps and placing buoys, and they had learned the shores and made valuable contacts with cooperative suppliers. Scott boasted that the British achieved “a better knowledge of the navigation of the Chesapeake than the American pilots themselves; indeed the Americans were fully persuaded that some of their own countrymen had turned traitors and guided us through its intricacies”—as indeed they had. Cockburn insisted that a decisive blow could be struck in the Chesapeake region if the British could deploy more men.57

Deserters

During 1813, desertion weakened the already undermanned British force. In late March, thirty sailors stole three boats to desert to the militia at Hampton. In early August, many more bolted from a camp on Kent Island, Maryland, where a narrow and shallow strait allowed easy access to the mainland. By August 23, nineteen British deserters, including a midshipman, had reached Easton on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. In late August, eighteen British sailors landed to seek some pigs in the bushes near Cape Henry beach, when seven “took to their heels and made off,” reaching the safety of an American militia guard.58

The Republicans celebrated every deserter as a triumph that proved the moral superiority of the republic over the empire. Desertion apparently revealed the prime weakness of the coercive empire: the alienation of its common sailors and soldiers, who longed “to quit their floating dungeons” to embrace the liberty of Americans. “If one hundred men are sent to shore, another hundred must be sent to watch them,” the Richmond Enquirer boasted.59

The Irish in the British service proved especially prone to desert often with the help of Irish Americans. In late April, during the British occupation of Spesutie Island, Major Wybourn discovered that four of his “best men” had deserted, persuaded by “an old Irish rascal who had been a labourer 14 years among the Yankees on this island.” Wybourn led a pursuit party, but the deserters escaped by wading across to the mainland, where “the four villains tossed their hats up, saying they were now Americans & tried to persuade” the pursuers “to join them.” To Wybourn’s relief his men “d[amne]d them for traitors & rascals & came back.”60

America enticed British deserters as the land of prosperity, liberty, cheap alcohol, and the same mother tongue. Employing “Jack,” the nickname for the common sailor, Lieutenant Scott lamented, “The captivating sounds of liberty and equality . . . have led astray many a clearer head and sounder judgment than falls to the lot of poor Jack.” The “land of freedom and plenty” allured men weary of “the regular and strict discipline absolutely necessary in a man-of-war.” Cockburn ordered his captains to minimize contact between their common sailors and American civilians “in order to avoid Corruption, Seduction, or the Seeds of Sedition being sown” among the crews. The British commanders had the unenviable task of fighting an enemy while closely guarding their own men.61

After a battle, the naval officers screened their new prisoners to cull anyone suspected of British birth or recognized as a deserter from the British service (even if he had been an impressed American). Most of those so detected were Irish by birth and Americans by choice. British captains also raided villages suspected of harboring deserters. At best, retaken deserters could expect a flogging followed by a return to hard duty on a warship. At worst, they were hanged from a ship’s yardarm as a warning to others. The Irishman Patrick Hallidan deserted from Kent Island on the night of August 15 in a stolen boat. Recaptured and convicted by a court-martial, he was hanged on August 28. Most deserters, however, got away into America.62

Already shorthanded when the campaign began, the warships suffered considerable attrition from sickness, a few combat deaths, and many desertions. In September 1812, Cockburn’s captains enumerated the crews for eight of his largest warships: they fell short of their full complement by 198 seamen and 56 marines (who were red-jacketed and musket-armed “sea-soldiers”). The desertions impaired the efficiency of the warships, and the remaining men bore a heavier workload, which increased their temptations to escape.63

The British needed able-bodied men who would resolutely fight the enemy rather than desert to him. A potential, partial solution lay in the hundreds of slaves who fled in stolen boats and canoes to seek refuge on the warships during 1813. Unlike the British sailor and marine, who anticipated a better life in the republic, the former slave would almost never desert. Cockburn sought to replace many of his white marines with black recruits: “They are stronger Men and more trust worthy for we are sure they will not desert whereas I am sorry to say we have Many Instances of our [white] Marines walking over to the Enemy.”64

Promoting slave escapes also seemed the perfect turnabout to punish the Americans for enticing Britons to desert. Codrington explained, “For surely if the Americans whilst at Peace with us encouraged the desertion of our Seamen & paraded them in triumph before our officers who were treated with the grossest insults, it is not unbecoming us to receive deserters from them when in open hostility against us, let their colour be what it may, using those deserters as soldiers or sailors according to the example they themselves set us. I hope, indeed, we shall punish them severely in this way.” British desertion helped to persuade the officers to embrace blacks as essential allies in the Chesapeake war.65

Fugitives

Americans dreaded that the British would promote a slave revolt to massacre white families, but the imperial government had, in fact, ruled that out. The imperial leaders heeded anxious West Indian planters, who bitterly opposed, as a terrifying precedent, any British promotion of a slave revolt in America. Britons also feared that Americans would exploit any slave-committed atrocities for propaganda that might make trouble in Parliament.66

On March 20, 1813, the British secretary of state, Earl Bathurst, codified the official policy in orders to Sir Sidney Beckwith: “You will on no account give encouragement to any disposition which may be manifested by the Negroes to rise against their Masters. The Humanity which ever influences His Royal Highness must make Him anxious to protest against a system of warfare which must be attended by the atrocities inseparable from commotions of such a description.” Bathurst did, however, authorize the Chesapeake commanders to recruit a few guides, enlist them “in any of the Black Corps,” and take them away as free men at the completion of their service. Bathurst emphasized, “You must distinctly understand that you are in no case to take slaves away as slaves, but as free persons whom the public become bound to maintain.” The Chesapeake commanders were supposed to minimize contracting “engagements of this nature, which it may be difficult for you to fulfill.” Leery of costs and complications, Bathurst wanted only a few black men useful as guides and no women and children.67

During 1813 the British naval officers first encountered Tidewater slaves as watermen paddling dugout canoes and small boats for fishing, crabbing, oyster-raking, and transporting goods. Their masters employed them to catch fish and crabs to feed the rest of their slaves. The oysters and better fish could also be marketed for cash in the seaports. Many Chesapeake slaves also worked as sailors on the sloops and schooners that carried cargoes up and down the bay.68

The watermen connected the naval officers to the enslaved communities on shore. On June 25, 1813, a white man saw a slave named Anthony fishing in the James River when a British boat came up and took him on board. Two weeks later, three young men escaped from Anthony’s neighborhood in a stolen dugout known as a “periauger”; two of them shared Anthony’s owner. Evidently Anthony had spread the word that the British would welcome young, male runaways who could help them. In late August on the Eastern Shore, Sam “was fishing on that day & must have seen the British fleet which came down the Bay on that day.” During the following night, “many negroes were missing from the said neighbourhood at the same time as well as canoes & boats.” The runaways included Sam.69

In addition to watermen, “outliers” made early contact with the British. Every Tidewater county had defiant malcontents who had escaped to hide out in makeshift camps in a forest or swamp. The appearance of British warships in the bay invited the outliers to flee to the warships. In March 1813 they included the three James City County runaways—Anthony, Tassy, and Kit—who mistook an American privateer for a British warship.70

Three other outliers, Joshua, Arnold, and Will, came from Northampton County, on the Eastern Shore. In July 1813 they also mistook an American privateer for a British warship. Severely flogged by the crew, they were dumped on the shore, where they resumed hiding out in the woods. Peggy Collins, a free black woman, secretly fed them. She later remembered that Arnold “seemed from the marks on his back to have been dreadfully beaten & that he begged her to ask his master to let him come home, that she did so & his master consented that he should come home & he would not whip him.” Joshua, Arnold, and Will returned to their masters, but neither the whipping nor the apparent pardons remade them into docile slaves. In May 1814 they organized a bigger and better escape, leading away thirteen other slaves, including Joshua’s wife and two children. In a stolen canoe, they paddled away on a night that “was clear & calm” so they “could hear distinctly . . . the drum & fife & fiddle from the shipping then lying opposite in the bay.” They deployed a clever ruse to distract the leading master, for Peggy Collins recalled that they “had a great dance the night they went away & said [if] they would dance & be merry, Master wouldn’t think they were going to the British.”71

In early 1813, the British attracted runaways primarily from the Virginia shores near the mouth of the bay, where the warships initially concentrated: from Princess Anne County to the west and Northampton County on the Eastern Shore. The commander of the Northampton County militia, Lieutenant Colonel Kendall Addison, offered to pay ransom if Warren would restore the runaways to their masters. Warren pointedly replied that the fugitives had become free by taking protection under the British flag on his ships. “At liberty to follow their own inclination,” they could not be sent back for any ransom. By flocking to the warships, the runaways pressured Admiral Warren into making decisions that fudged his restraining orders from Earl Bathurst.72

More runaways came forward on foot when British raiders landed to attack the Maryland villages. In early May, eighteen runaways followed a British foraging party back to HMS Sceptre. Reluctantly taking them on board, Cockburn sought further orders from Warren, who again directed their retention as free people. In late May, Warren reported to the Admiralty that his warships had received about seventy refugees “to whom it was impossible to refuse an asylum.” He added, “The Black population of these Countries evince, upon every occasion, the Strongest predilection for the cause of Great Britain, and a most ardent desire to join any Troops or Seamen acting in the Country, and from information which has reached me, the White Inhabitants have suffered great Alarm from the discovery of Parties of the Negroes having formed themselves into Bodies and especially with Arms in the Night.” In such reports Warren urged a new British policy of encouraging and arming runaways as the best means to intimidate their masters.73

The number of escapes surged during the summer and fall as word spread that the British officers welcomed runaways. In July, Lieutenant Colonel Addison reported to the governor, “The Negroes are frequently going off to them. Already we have lost from this County about one hundred & twenty Negro Slaves. Thus situated, sir, you can readily conceive our apprehensions.”74

In early November, Captain Barrie’s warships visited the Potomac, attracting many runaways in stolen boats. On Virginia’s Potomac shore, Major John Turberville reported that 100 slaves had fled “owing principally to the neglect of those whose duty it was in securing the boats, canoes, &c.” Walter Jones worried, “The Spirit of defection among the negroes has greatly increased. . . . No doubt remains on our minds that concert and disaffection among the negroes is daily increasing and that we are wholly at the mercy of the Enemy.” Jones feared that “clandestine Elopement” soon would ripen into “open Insurrection.”75

As growing numbers reached the British warships, the officers struggled to feed, clothe, and shelter them. In early September, Warren observed,

It is with great Difficulty that larger numbers have been prevented [from] joining us; 150 have come down in a body near the shore of the Potowmac just after we had left it. I could not refuse those which have got on board the ships in Canoes—men, women & children—amounting to about 300 as they would certainly have been sacrificed if they had been given up to their masters & destroyed our Influence among them, for at present every Slave in the Southern States would join us if they could get away.

In reports sent to London, Warren walked a fine line, insisting that he did nothing to attract the runaways but could not turn them away, although entire families came, including the women and children that Bathurst did not want.76

Captain Barrie also recognized the military potential of “the poor devils (the negroes) that were continually coming along side in canoes.” On November 14, 1813, he added, “The Slaves continue to come off by every opportunity, and I have now upwards of 120 men, women and children on board . . . and, if their assertions be true, there is no doubt but the Blacks of Virginia & Maryland would cheerfully take up Arms & join us against the Americans.” Although many masters had come under flags of truce to speak to their slaves, “not a single black would return to his former owner.” By the end of 1813, at least 600 Chesapeake slaves had escaped to the British, who sent many on to the naval base at Bermuda.77

Bermuda

During the war, Bermuda became the primary support base for the British squadron blockading the American coast. A cluster of low-lying islands about 600 miles southeast of Virginia, Bermuda was fourteen miles long, about a mile wide, and covered with cedar trees. From a distance, it made a delightful first impression on naval officers. Lieutenant Scott reported, “Bermuda assumes the aspect of a paradise when approached on a fine day. . . . The numerous islands reposing on its glassy lakes, and reflected as in a mirror by the clear blue sea, lend a degree of enchantment to the scene scarcely credible.” But first impressions proved deceiving, for the ships had to penetrate a long, twisting channel through rocks and around shoals to reach the harbor of St. George’s. And the town quickly depressed the officers as a grubby den of indolence and greed where the merchants and landlords charged exorbitant rates for their goods, provisions, and lodging. Admiral Cockburn dismissed Bermuda as “a vile Place.” Upon sailing away, Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm declared, “Thank God I am clear of Bermuda.” No naval officer would have predicted that Bermuda had a future as a tourist mecca.78

The refugees saw relatively little of Bermuda because the leading colonists wanted no more blacks, lest they tip the balance in the population, then approximately equal between the races. In August 1813 the legislature’s leaders denounced the “very considerable number of Negroes . . . lately imported into these Islands from the Coast of the United States” by British warships. The legislators feared “the most pernicious effects in this Colony” because “our black population is the principal cause of the Decrease of the white Inhabitants, whose total extinction would be the ultimate consequence.”79

But the colonial law of Bermuda did not apply to one of the islands—called Ireland—which belonged to the Royal Navy and where most of the refugees had to live and work. During the war the British expanded the fortifications and dockyard to service and repair the many ships operating along the American coast. Because white workers were in short supply, the dockyard hired refugees as laborers and carpenters. Each received a bounty, rations, and two shillings in daily pay, but he had to sign an indenture to serve for at least one year. In October 1813 the dockyard employed 100 black men and about 25 women and children. They lived in huts at the dockyard or on board a hulk anchored in the harbor: HMS Ruby.80

Some Chesapeake blacks balked at the hard work of the dockyard, which struck them as differing too little from slavery. A British officer concluded that “they considered work and slavery synonymous terms.” Admiral Cockburn informed the newly liberated that they had “a right to the Wages earned by their Labor, yet that they are not on this account to suppose themselves entitled to be maintained in Idleness and to be fed, cloathed, and Lodged without working . . . and that they are in all respects precisely treated herein as His Majesty’s English born Subjects.” The British officers invited the runaways into the partial freedom of the working class.81

Each dockyard worker received a daily ration which proved inadequate also to feed a wife and children, who demanded their own. A stickler for regulations and hierarchy, the dockyard commander, Andrew Fitzherbert Evans, had scant patience for complaints from blacks. He would provide rations to women and children only if they picked oakum: a tedious task. Work for food without pay seemed too familiar to them as slavery, so the women also demanded $4 a month. Evans nearly burst a blood vessel: “I am sorry to add that they evince a very riotous disposition and appear averse to any kind of Controul, professing as they have been led to believe that they are free men [and women] and subject to no restraint but their own Caprice.” Commiserating with Evans, Cockburn denounced the “riotous and improper Inclinations amongst these foolish and ever discontented People.” But the naval officers eventually compromised, for by April 1814, the women and children were paid as well as fed for picking oakum. The Royal Navy officers had to learn, through trial and error, how to work with the runaways who expected true freedom.82

Scouts

Black scouts improved the daring and performance of shore raids and eased the British dread of probing deeper into the countryside. Experienced at dodging slave patrols, the slaves had an intimate knowledge of the intricate Tidewater landscape of swamps, forests, and waterways. Along the James River in 1813, Lieutenant Scott wisely made friends among the enslaved: “Our means of security were afterwards greatly increased by the assistance of the negroes. Though several snares and ambushes were laid for me during our . . . services in the Chesapeake, I escaped them through the agency of my invisible friends.” Black guides also revealed hidden herds of livestock or storehouses filled with provisions and munitions. Masters struggled to keep secrets when runaways flocked to the invaders.83

With the help of their new guides, the British gained possession of the night. They usually launched their shore raids after dark, while the militia and planters slept and when the slaves were the special masters of the paths. Lieutenant Scott recalled,

The opportunities afforded us of safely traversing the enemy’s country at night, by means of these black guides, placed a powerful weapon in the Rear-Admiral’s hands. . . . The country within ten miles of the shore lay completely at our mercy. We had no reason to doubt the fidelity of our allies. . . . By their assistance we were enabled to pass the enemy’s patroles, make the circuit of their encampments, and cut off the post beyond it. The face of the country (generally thickly wooded) was propitious to these nightly excursions. . . . Before these useful auxiliaries came over to us, our nightly reconnaissance was necessarily circumscribed.

Formerly wary of the Chesapeake landscape, the British gained confidence after they recruited runaways for guides.84

As the land became more visible to Britons, it became murkier to slaveholders. In 1814 on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, a militia officer rued that four local blacks led a British raiding party “into an intricate position at or about midnight,” and we “could not ascertain any other mode by which information so accurate as the enemy certainly evinced, could have been obtained.” In addition to guiding Britons, blacks could mislead Americans. Called out to repel a British raid, a Maryland militia patrol got lost and offered a slave $5 to show them the road back to Baltimore. He promised to do so after first completing his errand “for some gentleman.” When the slave returned, he brought British troops, who surrounded and captured the lost militiamen.85

Proclamation

Admiral Warren urged his balky government to permit the recruitment of black troops in the Chesapeake: “The Black force could be augmented to any amount & being organized upon our Modes could be managed & kept within bounds and the Terror of a Revolution in the Southern States increased to produce a good Effect in that Quarter.” While keeping the blacks under military discipline, Warren could intimidate southern whites. With black troops, the British could “penetrate to Washington & Destroy the Dock yard & City.”86

Sir Charles Napier endorsed and expanded on Warren’s proposal. An especially bold army officer who commanded a regiment in the Chesapeake campaign, Napier wanted to recruit and arm thousands of runaways. Slaves, he insisted, would flock to his standard because they regarded the British as “demigods” and their masters as “devils.” Napier requested weapons for 20,000 recruits, a set of white officers, and 100 drill sergeants. After landing on the Eastern Shore, Napier would “strike into the woods with my drill men, my own regiment, and proclamations exciting the blacks to rise for freedom, forbidding them, however, to commit excesses under pain of being given up or hanged.” Napier planned to establish a free-black colony that would attract runaways from throughout the United States. Then his black army would march on Washington, D.C., to dictate a peace that would abolish slavery in America. Lacking Napier’s romantic imagination and bold optimism, the British rulers in London preferred a smaller black force more closely controlled by naval officers.87

In September 1813, Earl Bathurst authorized the Royal Navy to enlist Chesapeake runaways “into H[is] M[ajesty]s’s land or sea service.” Although Warren had proposed the new policy, implementation fell to his more aggressive successor, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, who took command of the North American squadron on April 1, 1814. In operations against the French in the West Indies, he had recruited and armed runaway slaves. Eager to escalate the war in the Chesapeake, Cochrane wanted to vigorously recruit runaways. Recalling a prewar visit to Virginia, he concluded, “From what I saw of its Black Population they are British in their hearts and might be made of great use if War should be prosecuted with Vigor.”88

Cochrane hated the Americans, in part because they had killed his beloved brother in the battle of Yorktown during the revolution. In 1814 that hatred became an asset to a government resolved to punish the Americans for prolonging the war. “I have it much at heart to give them a complete drubbing before peace is made,” Cochrane promised. “They are a whining, canting race, much [like] the Spaniel and require the same treatment—must be drubbed into good manners.” Humbling American pride remained a top priority.89

Vice Admiral Sir Alexander F. I. Cochrane, an oil portrait by Sir William Beechey. (Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England)

A hyperactive schemer, Cochrane suggested bribing some Americans to kidnap Republican congressmen: “A little money well applied will attain almost any object amongst such a corrupt and abandoned race.” He would hold the Republican leaders as hostages until their government released all of their British prisoners. A skeptical Cockburn replied, “I do not think any Yankee Senator or Member of Congress worth half the Money you seem inclined to give for them, but I will try what is to be done in the way you mention.” As with so many of Cochrane’s plans, however, realization lagged far behind his imagination. Sir Pulteney Malcolm complained, “Cochrane is all zeal. His first resolves are generally correct, but . . . his head is so full of schemes that one destroys the other.” Cockburn, however, worked well with a commander who shared his aggressive personality and ambitious goals.90

To obtain black recruits, Cochrane had to commit to their future as free men. On April 2 he addressed a cleverly worded proclamation to “all those who may be disposed to emigrate from the United States . . . with their Families.” He promised to honor “their choice of either entering into His Majesty’s Sea or Land forces, or of being sent as FREE Settlers to the British Possessions in North America or the West Indies, where they will meet with all due encouragement.” To deny the charge that he promoted a slave revolt, his wording avoided explicitly addressing slaves while emphasizing the word FREE as their future state as British friends. In a private report, Cochrane explained that he sought to harass the masters “and bring the consequences of the War home to their own Doors.”91

From his headquarters at Bermuda, Cochrane sent 1,000 printed copies of the proclamation to Cockburn for distribution along the shores of the Chesapeake. Incredibly, many American newspapers, including the Madison administration’s own National Intelligencer, also spread the word by reprinting the proclamation, albeit with hostile commentary. The National Intelligencer insisted that the proclamation was a scam to lure credulous slaves away for British sale “to a bondage more galling than the light servitude they now endure.” Whatever masters read, they talked about, which slaves overheard and interpreted in their own way.92

Cochrane issued the public proclamation on his own authority rather than on behalf of the imperial government: “in it I keep Ministers out of sight and take the odium and responsibility upon myself.” But in January 1814, Henry Goulburn, Bathurst’s undersecretary, privately had authorized Cochrane to welcome runaways “into His Majesty’s Service” or to become “free Settlers in some of His Majesty’s Colonies.” Goulburn sought to entice the many “Negroes and coloured Inhabitants of the United States” who had “expressed a desire to withdraw themselves from their present Situation.”93

In March, Cochrane had sent an advance copy of the proclamation to the Lords of Admiralty, but they carefully avoided taking a public position, pro or con, lest they bear responsibility for the new policy. In May, Bathurst reminded his Chesapeake commanders that the government opposed any effort to promote a slave revolt. Cochrane replied, “I entirely Agree with your Lordship that no steps should be taken to induce the negros to rise Against their Masters. My views go no farther than to afford protection to those that chuse to Join the British Standard.”94

Bathurst had preferred to attract only men, but his officers recognized that few would enlist unless promised a haven for their families. Captain Joseph Nourse explained that most of his refugees were women and children, “but there would be no getting the men without receiving them.” Bowing to that reality, the British government authorized the Royal Navy to “receive on board His Majesty’s Ships the families of such Persons, and in no Case to permit their Separation, the Assistance given to their families in the British Service being understood to be one principal Cause of the desire to emigrate, which had been manifested by the Negro population.”95

In addition to welcoming runaways who reached their ships, the officers aggressively went ashore to entice slaves to come away with them. As a central goal of the 1814 campaign, Cochrane ordered Cockburn to seek out and liberate slaves of both genders and all ages: “Let the Landings you may make be more for the protection of the desertion of the Black Population than with a view to any other advantage. . . . The great point to be attained is the cordial Support of the Black population. With them properly armed & backed with 20,000 British Troops, Mr. Maddison will be hurled from his Throne.” Cockburn promptly directed one captain, “You are to encourage by all possible means the Emigration of Negroes from the United States.”96

The new strategy reflected the lessons learned by British commanders in the Chesapeake during 1813, when they had struggled to keep white men from deserting and had failed to keep hundreds of slaves from fleeing to their ships. Making a virtue of necessity, the commanders recognized that the runaways offered invaluable local knowledge and potential as sailors and marines. Bending their orders from London, the admirals gradually embraced the many black refugees, including women and children. The commanders then persuaded their government to authorize recruiting blacks for war. By their courage, persistence, and numbers, the runaways enabled the British to adopt a new, far more aggressive strategy for 1814. Black initiative transformed the British conduct of the war in the Chesapeake.97

In early 1813 the Royal Navy officers did not intend to emancipate more than a few slaves, but scores of Tidewater slaves acted as if the British were liberators, escaping to them in stolen canoes and boats. Put on the spot, the naval officers took in the runaways: reluctantly at first but with growing zeal over time. The officers warmed to their new role as liberators as a chance to highlight American hypocrisy about liberty. By protecting runaways, the officers claimed moral superiority over the enslaving Americans. By the end of 1813 the naval commanders also realized that the blacks could provide invaluable services to the British campaign. The runaways had made themselves essential to the officers’ self-image and to their drive to humble the Americans along the shores of the Chesapeake.

Lelia Skipwith Carter Tucker, oil painting by an unknown artist, ca. 1815. Lelia Tucker was the second wife of St. George Tucker, the mother of Charles and Mary “Polly” Carter, and the mother-in-law of Joseph Cabell, who married Polly. (Courtesy of the University of Mississippi Museums)