[The Richmond Fire Bell] always produces a very great alarm in this Country . . . on account of the apprehension that it may be the Signal for, or Commencement of, a rising of the Negroes.

—ALEXANDER DICK, MAY 21, 18081

But this momentous question [of Missouri], like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. . . . But as it is, we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.

—THOMAS JEFFERSON, APRIL 22, 18202

DURING THE WAR of 1812, Virginians asserted their patriotic superiority over the New England Federalists, who had soured on the national government as they continued to lose elections and shrank into political insignificance except in the Northeast. When James Madison succeeded Jefferson to the presidency in 1809, the “Virginia Dynasty” seemed alarmingly perpetual to the Federalists of New England. Despairing of national power, they tried to consolidate their regional base by persuading local voters that the powerful Virginians meant to ruin New England’s mercantile economy, by imposing Jefferson’s embargo and Madison’s war.3

The Federalists denounced the Virginians as arrogant bullies corrupted by their power over abject slaves. In a letter to President Madison, a New Englander blasted, “[You] daily complain of G. Britain for pressing and enslaving a few thousands of your seamen, & yet you southern Nabobs, to glut your av[a]rise for sorded gain, make no scruple of enslaving some millions of the sons and daughters of Africa.” Trained to dominate, the slaveholders allegedly also sought to master the people of New England. In Congress, Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts hyperbolically warned that the next generation of New Englanders were “destined to be slaves, and yoked in with negroes, chained to the car of a Southern master.” The Federalists developed this critique to score political points in New England rather than to free slaves in Virginia. Quincy conceded, “My heart has always been much more affected by the slavery to which the Free States have been subjected, than that of the Negro.” By applying the term slavery to the political marginalization of New England, Quincy cast the leading Virginians as the indiscriminate tyrants of white as well as black people.4

During the war, northern Federalists predicted military disaster for a South weakened by the need to guard slaves as well as a long coast. In Connecticut, a Federalist newspaper warned southerners, “We do not know what you would do, between an external invasion on the one hand, and the internal dread of your slaves on the other.” Federalists insisted that the southern states needed the protection of northern troops, which they threatened to withhold to punish the Republicans for declaring an unjust war. In Massachusetts a minister preached, “Let the southern Heroes fight their own battles, and guard their slumbering pillows against the just vengeance of their lacerated slaves.”5

Honor

Prickly about their honor, southerners resented attacks on their character and hated the insinuation that they depended on northern protection. They also claimed an exclusive right to discuss the internal enemy—and only among themselves. The Richmond Enquirer warned that northerners gave slaves “false ideas of their strength and prompts them to an attempt, which, with whatever horrors its progress might be attended, must inevitably terminate in their ruin.”6

Virginians privately obsessed about their danger from the “internal enemy,” but they wrote very differently when publicly refuting their northern critics. In April 1813, the National Intelligencer denied that the South risked a serious slave revolt: “The slaves in general are well-disposed. . . . We believe the negroes themselves, on the approach of an invading force, would, if permitted, gladly advance to repel it. The slaves in the South are, in general, a peaceable, inoffensive race content to do the duty to which they were born, and attached to the families from whom they respectively receive protection and support.” During the war and under the pressure of northern criticism, the South’s spokesmen developed the pro-slavery case that would blossom in future decades. Deemphasizing the threat of an internal enemy, the emerging pro-slavery ideology dwelled instead on the alleged stupidity, docility, and happiness of slaves protected by their paternalistic and superior owners. But the war did not allow the southern press to stay on that slippery message, for the next day the same newspaper warned that the British had just landed on Kent Island, Maryland, where “Several negroes had deserted to them and become pilots for them in plundering.”7

Proud of their sacrifices in fighting the empire, the Virginians despised the many New Englanders who sympathized and traded with the enemy. Making much of their own honor, the Virginians denounced the Yankees as corrupted by greed. A Virginian boasted that the war would “prove to our Yankee brethren that Southern patriotism is not to be estimated by Dollars and Cents.” Rigorously blockaded by the British, the Virginians seethed when the enemy initially exempted the New Englanders, who profited by trading with the foe. Compelled to rally thousands of militiamen for service, the Virginians also resented that New England’s Federalist governors refused to mobilize their militia for federal service. Virginians blamed the American defeats in Canada on New England’s failure to assist the war effort. “If the New England men wou’d now do their duty, Canada to the works of Quebec wou’d be ours,” insisted Wilson Cary Nicholas. While the British spared New England from raids and invasion until 1814, when they seized eastern Maine, Virginia bore the brunt of British animus. Governor James Barbour claimed that the British targeted Virginia for destruction from “a deadly and implacable hate, the result of the magnanimous and distinguished part acted by Virginia in resisting at all times British aggressions.”8

The Virginians regarded the New England Federalists as insidious traitors. St. George Tucker concluded that the Yankees were “determined to rule or to dissolve the union.” Britain “is promised civil war by our Northern Traitors,” agreed Dr. Philip Barraud. A Virginia veteran of the revolution, Colonel John Minor, recalled, “It was my lot . . . in the last war to see in the Southern States the Horrors of a Civil War, at the recollection of which I now shudder and feel an indignation against those bad men, who by attempting to divide the nation, threaten us with a Civil War.”9

By fighting the British, the Virginians meant to vindicate their military prowess and save the republic. Barbour vowed to defend “the ark of our political salvation—the Union of these States” from “all the horrors of civil war.” John Campbell assured the Yankees, “If you raise the standard of rebellion, your green fields will be wash’d with the blood of your people and your country laid desolate by the flames of civil discord! If you attempt to pull down the pillars of the Republic, you shall be crush’d into atoms.” In late 1814, Thomas Jefferson predicted that Virginians would rather fight New Englanders than the British: “we can get ten men to go to Massachusetts for one who will go to Canada.” During the War of 1812, Virginians opposed secession, in contrast to the stand they would take fifty years later.10

The Virginia officers in the national army worked up a great dislike for their northern colleagues as inept, corrupt, and sorely lacking in southern honor. Colonel S. B. Archer declared, “I have my doubts whether even now the Northern and Eastern section of this Country are not too far gone in depravity ever by themselves to be regenerated.” After denouncing one cowardly scoundrel, Colonel Isaac A. Coles noted, “I need not tell you that this man was not a Virginian.” Returning home from national service, Nathaniel Beverley Tucker assured his father, “I have come back into old Virginia, more of a Virginian than ever, and as to Messrs. the Yankees, I love them not.”11

In early 1813, James Madison appointed an ambitious New Yorker, John Armstrong, as the secretary of war. Armstrong quickly offended the army’s southern officers, who felt slighted and passed over for promotion in favor of northern men. Southerners suspected that Armstrong used patronage to build a political following that could elevate him to the presidency in 1816 at the expense of his great rival, James Monroe of Virginia. Southern officers felt especially miffed when the northern politicians William Duane and Jacob Brown gained powerful roles in Armstrong’s army. Several Virginia officers resigned in a huff, denouncing Armstrong as “an unfeeling & unprincipled Scoundrel.” Brigadier General Thomas Parker explained that he would never “Submit to the degradation of being Commanded by Mr. Brown.”12

Armstrong also offended Virginia’s leaders by failing to repair and garrison Fort Powhatan, which guarded the approach to Richmond via the James River. Located at Hood’s Point on a high bluff thirty-five miles south of the city, the fort could block the ascent of British barges. But the secretary of war delayed for months any reply to Governor Barbour’s urgent request to rebuild the fort. Then Armstrong unwittingly added insult to injury by forwarding a discouraging report by Colonel John Swift, a military engineer, who declared the fort “worthless” for “any other purpose than that of affording a point of security to the inhabitants in the vicinity of the Fort in case of the insurrection of negroes.”13

In private appeals to their state government, Virginians obsessed about an impending slave revolt. Indeed, Armstrong and Swift were far less explicit than the Richmond Committee of Vigilance, chaired by the mayor, which privately warned the state government that if the British captured the fort, “A Saint Domingo Scene will be exhibited.” But Virginians felt insulted when a northerner made the same point in a public and official statement, for they had grown especially sensitive to northern charges that slavery weakened the South’s capacity for self-defense. When the nation failed to protect Virginia against British raids during the war, the state leaders felt doubly offended by any suggestion of southern weakness and dependence on the North. Worse still, the legislators considered Armstrong’s letter and Swift’s report at the same time that they heard, in February 1814, that the War Department balked at compensating the state for the heavy costs of the militia force posted at Norfolk.14

In a pointed retort, the House of Delegates insisted that Virginia had long defended the nation and “has never found it necessary to call on the U[nited] States to secure her repose against an interior enemy nor does she at present urge any such claim for protection.” Joseph C. Cabell, a state senator, explained, “The style of Genl. Armstrong’s & Col. Swift’s letters have given offence to all parties here . . . and that, as they had not been consulted as to the utility of Fort Powhatan as a position of defence against an insurrection of slaves, they might have abstained from any intimations of a nature calculated to wound the feelings & degrade the character of the state.” The episode shook the confidence of Virginia’s leaders in the president for retaining the despised Armstrong as a counterweight to Monroe in the cabinet. Cabell attested that Barbour felt “treated with great neglect if not contempt by the Secretary of War.”15

Nationalisms

During the crisis of 1814, Virginia’s leaders rallied men to defend the state rather than the nation, appealing to their pride as Virginians rather than to their patriotism as Americans. Noting the nation’s failure to defend the state, the Richmond Enquirer exhorted:

Virginians! Brave Virginians! You have every motive to rouse you. Remember Hampton! Remember the Northern Neck! Call to mind the wrongs you have suffered, the slanders which have been heaped upon you by the mercenary prints of the enemy! . . . Virginia is now thrown upon her own resources. Her sons must show that they are equal to her defence. The eyes of the Union are upon us: shall we draw upon us their scorn? The bones of our fathers sleep in our soil; shall we suffer a foreign enemy to trample on them?

Knowing his readers well, the author cited only atrocities and insults directed against Virginians, and he invoked the Union only as an external audience eager to scorn them.16

In 1788 Virginia had narrowly and reluctantly ratified the Federal Constitution in response to Madison’s hopeful promise that a stronger union would amplify the state’s power on a continental scale. The War of 1812 put that promise to the test, and Virginians concluded that the nation had failed them by neglecting their defense and insulting them with Armstrong’s response regarding Fort Powhatan. The nation also proved impotent to compel cooperation from the New England states, which escaped the brunt of a war borne by Virginia. In addition, the Madison administration sought to buy northern support by reserving key positions in the War Department and the army for men of suspect principles and abilities.

If the Union could not fulfill Madison’s promise to Virginia with Madison as president, what could the state expect from a northern leader in the future? The hated Armstrong crashed and burned politically in August 1814, when he became the scapegoat for the British capture of the capital, but perhaps some other New Yorker—DeWitt Clinton or Daniel D. Tompkins—might succeed in building a national coalition to govern the nation without Virginia. While Virginians began the war as champions of the Union, they ended it with powerful new doubts. Feeling betrayed for their wartime nationalism, the Virginians sought support from the other southern states against the distrusted northerners, who seemed poised to seize control of the Union. The South began to become Virginia’s nation during the War of 1812, but this was a slow process that did not fully mature until the secession of 1861.17

Historians often note the surge in American nationalism that immediately followed the War of 1812. As never before, newspapers and orators celebrated patriotism, while displays of the flag and the eagle proliferated in engravings, paintings, and taverns. But that effusive nationalism was, ironically, highly sectional: strongest in the Middle Atlantic and western states and weaker in Virginia and other southern states. In fact, the war generated competing nationalisms, for the southern states developed a far stronger bond and shared identity with one another. As a consequence of the war, southerners felt suspicious of the Middle Atlantic version of patriotism, which we often mistake for the sentiment of the entire nation. Rather than promoting a unifying nationalism, the experiences of war bred distinct regional variants.18

At war’s end in early 1815, Virginians exulted in Andrew Jackson’s great victory at New Orleans as a vindication of the South rather than of the nation. As a Tennessee slaveholder and Anglophobe, Jackson appealed to the South far more than did any northern-born commander. The Norfolk doctor Philip Barraud assured St. George Tucker that Jackson’s triumph

established the claims & reputation of the Southern portion of this Empire. The people of the East shall hence forth no longer dare to charge on this section of the States the foul calumny of seeking wars without the spirit to maintain them with valor or with their Blood. . . . It fixes the power & ability of these states to protect their Firesides & to punish their Enemies without Yankee aid. . . . It teaches England that we are not weak, altho we have Slaves & rich Lands. It establishes beyond all doubt that the South is the soil for Generous, Loyal & valorous men.

By contrast, Barraud recalled “the never-to-be-forgotten turpitude & traitorous conduct of the Eastern portion of our Nation.” Tucker agreed that the “Explosion of Joy for Jackson’s Victory” exceeded anything he had ever experienced in Virginia.19

To celebrate the peace, Richmond staged a grand illumination with candles in the windows, bonfires on the hills, rockets in the air, and patriotic paintings on the public buildings. Everywhere Jackson’s image stole the show. “The favorite figures of the evening were ‘Jackson’ and ‘Peace,’” reported the Richmond Enquirer. The “Wax-work Museum” displayed “a transparent scroll with the name of Jackson,” while the state capitol presented “a large transparent painting” featuring “a triumphal crown surrounded by Cornucopias and encircling the name of ‘Jackson’ with that never-dying day, ‘The 8th of January 1815.’” Next to Jackson, the displays honored the leading Virginians, Madison and Monroe, with a couple of naval heroes thrown in—but it was revealing that no generals from the North appeared. Of course, northerners also claimed Jackson for their nationalism, but they linked him with their own heroes in a bigger cast, while Virginians detached and elevated Jackson as the one great champion of southern nationalism.20

In addition to its geopolitical significance in discouraging the British from again waging war in North America, the Battle of New Orleans reshaped America’s political culture. Southerners interpreted the battle as proof of their superior honor and fighting ability in stark contrast to the selfish and corrupt northerners. By claiming martial superiority, southerners refuted northerners who charged that slavery rendered their region weak and dependent on the North. After the war, when some Virginians proposed establishing a national committee to raise subscriptions to aid the families of dead or disabled militiamen, St. George Tucker responded, “We are not enough one nation for such a plan to succeed.” He expected that only state initiatives could raise the funds.21

Colonization

The War of 1812 gave Virginians a great scare, revealing the military potential of black troops deployed against them. Long a specter, the internal enemy had become real in the red coats of British troops rather than as the anticipated murderous massacre at midnight. But the Virginians persuaded themselves that the black troops had brought their state to the verge of a “Saint Domingo Scene.”

Fears of insurrection surged in February 1816, when the magistrates in the Piedmont counties of Spotsylvania and Louisa discovered a plot organized by George Boxley. A storekeeper, farmer, and militia officer, Boxley owned a few slaves, which made him an unusual leader for a slave uprising. But he became embittered after the leading men of Spotsylvania blocked his ambitions to gain promotion in the militia and win a seat in the legislature. Frustrated by his wartime militia service at Norfolk, Boxley longed to smite Virginia’s leaders on behalf of a just and vengeful God. Addressing slaves at his store, Boxley declared that God had charged him “with the holy purpose of delivering his fellow creatures from bondage; that a little white bird had perched upon his shoulder and revealed it to him.” He recruited about thirty young men for a plot to steal arms and horses for a mass escape (after robbing the Fredericksburg banks) northward to a free state. A local writer noted, “The negroes were mostly actuated by an irresistible idea of freedom.”22

In late February, however, an anxious female slave tipped off the magistrates, who began to make arrests and increase slave patrols. Driven to act prematurely, Boxley could rally only about a dozen followers, and they quickly lost confidence in the scheme and slipped home to resume their slavery. Although the plot collapsed far short of any violent acts, the terrified magistrates arrested, tried, and convicted eleven slaves, sending five to the gallows and six into exile by sale and transportation. Convicting Boxley proved harder because all of the witnesses to his treason were black and therefore barred by Virginia law from testifying against a white man. Uncertain what to do with Boxley, the authorities kept him in jail until May 14, when he escaped after breaking his irons and cutting a passage through the ceiling of his cell. His visiting wife had smuggled in a file, perhaps with the complicity of the jailer. Suspicions arose that some powerful local people wanted Boxley gone rather than risk an embarrassing trial that would acquit for lack of evidence. He fled north, eventually settling in Indiana, where he became a prominent preacher and radical abolitionist. He left behind a Virginia more troubled than ever by its growing black population.23

Once again, Virginians blamed free blacks for resistance among the slaves. In an 1817 petition to the state legislature, the citizens in Isle of Wight County argued that free blacks tended “to promote insubordination & a spirit of disobedience among the slaves, & finally to lead to insurrection & blood.” In fact, during the war, while hundreds of slaves fled to the British, almost all the free blacks had remained loyal to Virginia. But they made tempting scapegoats because getting rid of them would deprive no white man of his property. By reiterating that their greatest danger came from free blacks, Virginians ensured that they would lament but never end slavery.24

Although still modest in number (30,570 in 1810), the state’s free black population was growing at a faster rate (22 percent from 1810 to 1820) than either the free white (9 percent over that decade) or the slave populations (11 percent). Because the state barred the import of slaves or the advent of free blacks, the growth in the black population derived entirely from their natural increase. By comparison, Virginia’s white population grew more slowly because diminished by outmigration to the southern and western frontiers during the 1810s. Poor whites without slaves dominated that free migration, so their departure tended to reduce the white proportion of Virginia’s population. At the same time, masters did sell thousands of slaves to the Deep South. During the 1810s, that coerced migration cut the growth in the slave population to half that of the free blacks in Virginia. Reluctant to move elsewhere because other family members remained enslaved nearby, free blacks proved the most loyal to Virginia as measured by persistence. White Virginians, however, felt threatened by that persistence.25

To reduce the black population, many Virginians promoted the postwar African colonization movement. A prominent Virginia politician, Charles Fenton Mercer, took the lead after finding inspiration in his discovery of the previous effort, in the wake of Gabriel’s rebellion, by the state government to seek a foreign colony for free blacks and perhaps emancipated slaves. In 1801–1802, Governor Monroe and President Jefferson had tried but failed to find an overseas haven. In 1816, however, Mercer felt a new urgency and sensed a new opportunity. The urgency came from the threats of violent upheaval demonstrated by the British invasion, the Colonial Marines, and Boxley’s plot. The opportunity came from the postwar burst of enthusiasm for ambitious new measures to improve the republic. In December 1816 in Washington, D.C., Mercer assembled elite men to organize a national society to promote African colonization. Drawn from both the North and the upper South, and from both political parties, the founders included such prominent Virginians as James Madison, John Marshall, James Monroe, John Randolph, John Tyler, and Bushrod Washington (a Supreme Court justice and the nephew of the late president).26

Disdaining blacks as well as slavery, the colonizationists wanted to whiten America. Madison sought to remove “from our country the calamity of its black population.” Mercer deemed slavery “the blackest of all blots, and foulest of all deformities” on American society, but he regarded free blacks as even worse: a motley set of prostitutes and thieves. An opponent, William Branch Giles, charged the colonizationists with exaggerating the immorality of free blacks for popular effect: “It would be unjust to put down the whole colored population as dissolute and burdensome, but the free people of colour are despised, and there is a rage about getting rid of them. . . . This being the most seductive inducement, it is accordingly the most used by the friends of the project, and to produce its greatest effect, it is greatly exaggerated.” Giles described most of the free blacks as “honest labourers, whose labour adds to the wealth of the State.”27

Protective of private property, the colonizationists insisted that slaves could be freed only with the consent of their masters; that whites could not coexist peacefully with any large number of free blacks; and that white prejudice was so deep and immutable that free blacks would never escape from poverty and degradation within America. Therefore, the colonizationists reasoned, everyone would benefit from shipping free blacks away to Africa—perhaps to be followed later by the more numerous slaves. Claiming that the republic needed a purely white population, the colonizationists refused to consider the alternative of a multiracial republic of equal citizens. John Randolph declared that the races could never “occupy the same territory, under one government, but in the relation of master and vassal.”28

The colonizationists spoke and wrote softly about slavery lest they alarm the southern majority averse to any public discussion. One member conceded “that Slavery must be touched with great delicacy and that any attempt to unsettle the state of the Slaves would be considered as kindling a fire of destruction.” Although dread of the internal enemy motivated the colonizationists, that dread also starkly limited what they could say or do, for slaveholders in the Deep South distrusted colonization as a covert abolitionist plot against their property.29

Most members vaguely hoped that an African colony would encourage more masters to manumit and deport their slaves, but many southern members, including Randolph, supported colonization only as a means to protect slavery by deporting free blacks. And many members continued to own, buy, and sell slaves. In 1821 the president of the national society, Bushrod Washington, sold fifty-four slaves to the Deep South, for he needed the money to pay his debts more than his conscience needed consistency. This younger Washington showed far less principle than his late, great uncle, who had emancipated all of his slaves while providing funds to care for the elderly and train the young. But George Washington had lived and died before the great decay of Virginia’s economy, a downturn that accelerated after 1816, compounding the debts and sapping the scruples of his heirs.30

The more daring colonizationists sought a government program, either federal or by the states, to emancipate the slaves gradually by compensating their masters and deporting the freed. The reverence for private property ruled out any immediate and uncompensated abolition of slavery. But that solicitude for property also meant that few Americans would tax themselves to raise the massive compensation required to free and transport over a million slaves. And most slaveowners preferred to retain the labor of their slaves and profit from selling their offspring rather than accept any compensation.

Given the prohibitive cost of deporting the most expensive slaves—those in the prime of their working lives—the gradual emancipation proposals focused on buying infants, particularly girls, as the most cost-effective way to shrink the slave population. The chief proponent of this scheme, Thomas Jefferson, dismissed the suffering that losing children would cause to black families as inconsequential compared to the good of the republic and the superior “happiness” of their children once free in Africa.31

In fact, Virginia could never afford to purchase and export enough slave children to make a difference. In early 1820, Thomas Mann Randolph Jr., Jefferson’s son-in-law and the governor of Virginia, urged the legislature to appropriate a third of the state’s revenues to buy and deport slave children, but the legislators balked at spending the taxpayers’ money to get rid of their valuable property. While far too expensive for the legislators, the governor’s program would have bought a mere tenth of the annual increase in the state’s slave population. Even if dedicated entirely to buying and deporting slaves, Virginia’s annual budget could not stop the increase in slave numbers—much less fulfill the fantasy of eliminating black people in America while respecting the property of whites.32

In addition, very few free blacks wanted to go to Africa: a distant continent that they had never known, for most were third- or fourth-generation Americans. Seeking equal rights in America, they preferred to stay and tough it out rather than take a dangerous leap into the unknown of West Africa. Indeed, the new American colony there, Liberia, was a malarial deathtrap and war zone for the 12,000 who did emigrate. Madison conceded that his slaves had a “horror of going to Liberia.”33

Mercer and Monroe overplayed their hand by obtaining financial and naval assistance from the federal government to subsidize and protect the shipment of blacks to Liberia. The federal involvement horrified southern conservatives, such as Randolph, who dreaded any intervention by the United States in slavery as setting a precedent dangerous to the South. They feared any expansion of federal power as a slippery slope that could lead to enforced emancipation by the Union. Consequently, the conservatives bolted from the colonization movement during the mid-1820s. Randolph explained, “I am against all colonization, etc. societies—[I] am for the good old plan of making the negroes work, and thereby enabling the master to feed and clothe them well, and take care of them in sickness and old age.” The defection by the states’ rights men reduced the colonization movement to a hollow, pointless shell even before the northern abolitionists renounced it as a fraud during the next decade. There could be, and would be, no consensus solution to the problem of slavery in America.34

Diffusion

In 1819 Virginia remained the preeminent slave state, home to nearly a third of the nation’s one and a half million slaves. Virginia’s leaders believed they had too many slaves for their own safety and more than their economy demanded. Rather than free slaves and deport them, Virginians preferred to sell them or to move away with them. By “diffusing” slaves to the new states of the Deep South and the West, Virginians could reduce the annual increase in the number enslaved more effectively and profitably than could any program of overseas colonization. Diffusion cost taxpayers nothing and precluded any role for the federal government. And the proponents could still claim that they opposed slavery in principle because diffusion allegedly benefited the enslaved. They would leave a crowded and depleted country for the western land of milk and honey, where they could be better fed, clothed, and housed by more prosperous owners. In the West, slaves supposedly could live with fewer constraints because the whites there felt more secure in their great majority. Some Virginians even argued that diffusion might prepare white people to embrace emancipation once slaves became small minorities spread evenly across a vast land. “An uncontrouled dispersion of the slaves now in the U.S. was not only best for the nation, but most favorable for the slaves,” concluded Madison.35

After the War of 1812, southern settlers and their slaves surged westward into the vast and fertile watershed of the Mississippi River. By 1820, the enslaved population west of the Appalachians had doubled during the preceding decade. In 1818, Randolph lamented: “Alibama is at present the loadstone of attraction: Cotton, Money, Whiskey & as the means of obtaining all those blessings, Slaves—the road is thronged with droves of these wretches & the human carcase-butchers, who drive them on the hoof to market.” A romantic traditionalist, Randolph rued the outmigration of slaves as a failure of paternalism in Virginia. He wanted Virginians and their slaves to stay put, but Randolph fiercely opposed any government interference with the rights of masters to buy, sell, or move their human property at will. If the alternative was restriction by federal power, Randolph preferred diffusion.36

The Virginians in Congress got a rude shock on February 13, 1819, when James Tallmadge Jr. of New York proposed amendments to a bill to admit Missouri as a new state in the Union. Tallmadge wanted to require Missouri to adopt a constitution barring further slave imports and committed gradually to emancipate slaves born after 1819. Most northern congressmen, Republicans as well as Federalists, supported Tallmadge’s amendments, for they believed that slavery contradicted and, therefore, threatened free government. Jonathan Roberts of Pennsylvania insisted that slave states were “marred as if the finger of Lucifer had been drawn over them.” By restricting the expansion of slavery, the “retrictionists” sought to preserve the West for free white settlers, who alone could sustain a true republic (so they argued).37

Restrictionists denounced diffusion as a fraud. John Sergeant of Pennsylvania demanded, “Has any one seriously considered the scope of this doctrine? It leads directly to the establishment of slavery throughout the world.” Restrictionists argued that diffusion thrust slaves into the greater hardships of the frontier and ruptured their families. And far from promoting antislavery sentiment, expansion swelled the western demand for slaves, inflating their value in the Chesapeake states. An abolitionist, Robert J. Evans, asked, “Should this odious privilege of enslaving fellow creatures be extended to the immense region beyond the Mississippi, will there not be a never failing market open for the commerce in human flesh[?]” If so, Virginia would “furnish to this great mart of men, a never ending supply.” If diffused, slaveholding would become predominant and perpetual in the nation.38

In response, southern congressmen denied that Congress had any legitimate authority to impose restrictions on a new state. Southerners claimed to defend the Federal Constitution and the rights of the states, rather than slavery, by opposing restriction. They denounced restriction as a cunning ploy meant to reduce the South to poverty and dependence within a nation dominated by the North. Rather than any sympathy for slaves or solicitude for free government, the restrictionists manifested, in the words of Spencer Roane (Virginia’s leading judge), “their lust of dominion and power.” Roane insisted that the controversy was “forced upon us by the cruelty and injustice of northern intriguers.” Opposing any restriction on slavery’s expansion, Nathaniel Beverley Tucker declared, “Let this precedent be once established and the power of the southern states is gone forever.” Southern congressmen feared the political implications of the more rapid population growth in the North, which already had 20 percent more free people than the South.39

The South could ill afford to become a minority region defined by slavery and confined within a geographic line. Restriction would dishonor the South as insufficiently republican because tainted by slavery. National power would accrue to the region that gave shape to western expansion. “It is indeed not a question of freedom or slavery, but a question [of] who shall inherit our rich possession to the west,” Isaac A. Coles explained. The North could claim the nation’s future by preempting that vast and promising region for its own people and institutions. Dabney Carr warned that once empowered by the West, the national North could “draw a cordon round us & when they had cooped us up on every side . . . then should we feel the full weight of their tender mercies!” If restricted, the South would become a claustrophobic corner of growing poverty and weakness in the Union.40

Virginia already was reeling from a great economic decline. In 1819 the entire nation endured its first massive economic depression, and no state suffered more than Virginia. The depression derived from a sharp downturn in foreign demand for America’s agricultural exports, especially Virginia’s tobacco, flour, and wheat. From 1818 to 1821, Virginia’s exports fell by 56 percent, compared to 42 percent for the nation as a whole. As foreign demand dried up, the price paid for farm produce in Richmond declined by 48 percent between November 1818 and February 1821. Virginians struggled to pay their debts when they could no longer sell their crops for a decent price. Bankruptcies and land sales surged. From Richmond in early 1820, Francis Walker Gilmer mourned, “Things here grow worse & worse—the merchants all failed—the town ruined—the banks broke—the Treasury empty—commerce gone, confidence gone, character gone.”41

The Missouri crisis erupted when the Virginians already feared for their diminished place in the nation. Restriction threatened to limit the western market for slaves and the West as a haven for slaveholders just when Virginians most needed that outlet. Governor William Branch Giles wanted the West to remain “an almost boundless reservoir for the reception of slaves.”42

Nothing terrified Virginians more than the prospect of being trapped within a state with a growing black majority in the Tidewater and Piedmont regions. Spencer Roane bluntly explained that Virginians were “averse to be dammed up in a land of Slaves, by the Eastern people.” Dreading a massive slave revolt, Roane declared that northerners regarded restriction as “an abstract question; but it is, as to us, a question of life or death.” Similarly, John Tyler warned that restriction would increase the “dark cloud” of slavery “over a particular portion of this land until its horrors shall burst.” Only with a vibrant interstate slave trade, and an untrammeled western expansion by slaveholders, could Virginians vent enough slaves annually to release the demographic pressure that, to their minds, threatened an inevitable race war. It was telling that Thomas Jefferson bitterly opposed restriction and declared that the Missouri crisis, “like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror”—for Virginians associated a fire bell’s alarm with a slave revolt.43

During the Missouri debates, congressmen from all regions threatened disunion and civil war, but the southerners showed greater unity and passion, for they felt more imperiled in their property and security. Randolph declared, “God has given us the Missouri and the devil shall not take it from us.” In February 1820, alarmed moderates saved the union by crafting a compromise. Maine (previously part of Massachusetts) became a free state, while Missouri joined without any restriction on slavery, thereby maintaining the balance in the Union, and so in the Senate, of eleven free states and eleven slave states. Congress also imposed a line west of Missouri to the Pacific along the 36°30' latitude (an extension of Missouri’s southern boundary), barring slavery to the north, where most of the remaining federal territory lay. While the South got Missouri, it faced a future of many more free states entering the Union.44

President Monroe and Senator James Barbour (the former governor) supported the compromise as essential to save the Union, but most of Virginia’s congressmen and state leaders angrily opposed any western restriction on slavery. The state legislators voted 142 to 38 to instruct their U.S. senators to reject the compromise. Nineteen of the twenty-two Virginia congressmen voted against the 36º30' restriction line; no state delegation provided more negative votes or more fiercely opposed any compromise.45

Despite their disgust with the Missouri Compromise, most Virginians were not prepared for secession and civil war as the alternative. In the Richmond Enquirer, Thomas Ritchie grumbled, “We submit. . . . We bow to it, though on no occasion with so poor a grace and so bitter a spirit. The South and the West are wronged, they must bear up patiently.” After 1820, Virginians adopted a selective and conditional nationalism. They supported the nation when it served their interests, as it usually did, for the South enjoyed a political clout disproportionate to the region’s declining share of the nation’s population. That power derived from the greater cohesion of the southern congressmen when compared to their northern counterparts. The defense of slavery and its expansion provided a far tighter bond for southern leaders than antislavery did for the more numerous northern congressmen. Southerners cherished a robust national government that enforced the fugitive slave law in northern states, compensated masters for wartime runaways, and pushed expansion southwestward into Texas. Southerners cheered when the nation acted on the racial dread of an alliance by the British with Indians and blacks. But southern leaders scuttled back to a states’ rights sectionalism at the slightest hint that northerners might deploy federal power to tax slaves or limit slavery. By loudly threatening secession, the southerners could alarm enough northerners, solicitous of the Union, into retreating in Congress.46

Fear

While fending off northerners, Virginia’s leaders also faced unrest within the state. Based in the Piedmont and Tidewater, Virginia’s elite confronted discontent from the people living west of the Blue Ridge in the Shenandoah Valley and Allegheny Mountains. The westerners felt trapped in underdevelopment because neglected by a state government dominated by easterners who enjoyed disproportionate power under Virginia’s antiquated state constitution. The old constitution also imposed a property requirement that disenfranchised the poorer half of the state’s white men.47

The westerners demanded a convention to draft a new state constitution. In October 1829 in Richmond, they got such a convention, but most of the delegates came from the Piedmont and Tidewater, so it produced only modest changes in the new constitution. The delegates slightly widened the electorate, reducing the disenfranchised to a third of white men. Legislative representation, however, remained skewed in favor of the eastern elites, who insisted that they could not trust the westerners to protect slavery. Appalled by the prospect of majority rule, John Randolph declared, “I would not live under King Numbers.” Thanks to the power of property in Virginia, he did not have to.48

A recent insurrection alarm had hardened the convictions of the eastern conservatives during the run-up to the convention. In mid-July 1829, panic had rippled through the Tidewater counties, filling the jails with slaves suspected of plotting a bloody rebellion. Once again, the alarm began with the overheard talk of blacks, who had responded to what they heard from whites. During that summer the white folk buzzed with speculation about the fate of slavery under the new state constitution anticipated from the convention scheduled to meet in the fall. In turn, hopeful slaves spoke of gaining freedom from the new order. Then alarmed whites interpreted that wishful thinking as, instead, a plot to seize freedom by bloodshed.49

The scare began in Mathews County, a Tidewater county that had suffered from British raids during the War of 1812. On July 18, 1829, Christopher Tompkins, who figured so prominently in the war, reported to Governor Giles, “About ten days ago information was communicated confidentially by a negro to a widow woman that it was expected generally among the slaves that they were to be free in a few weeks.” Two white apprentices overheard and reported similar chatter by slaves gathered at a blacksmith’s shop. Arrests and interrogations revealed “the general belief among the blacks . . . that the late convention election had exclusively for its object the liberation of the blacks & that the question had been decided by the result of the convention election & that it had been kept secret from them & that their free papers had been withheld improperly but were to be delivered at August court.” The slaves had updated the old myth of emancipation by a liberator king who had been frustrated by selfish masters. In the new version, “King Numbers”—the Virginia voters—had promised freedom. In fact, this American monarch had less substance as a liberator than had the old British king.50

The alarm in Mathews County became contagious, echoing through anxious letters carried across the Tidewater, into the Piedmont, and on to the state government in Richmond. Following the usual script, fearful whites sought to share the news without tipping off the slaves to the panic, but the enslaved could hardly miss the frantic conduct of masters and patrollers. In Hanover County on July 26, Colonel Bowling Starke reported, “The alarms have been of such a character that they could not be concealed from the negroes. They all know it and know our situation,” by which he meant the militia’s lack of guns. The agitation among the whites bred more slave talk, which escalated the alarm. A member of the Council of State noted, “These rumours have been much talk’d of by the slaves themselves & have probably increas’d the spirit of insubordination.”51

The alarm was especially great in Hanover County, where the county court had tried and convicted three slaves of conspiring and killing their master. On June 29, they had ambushed and shot William Boyers after discovering his intent to have “dispersed them over the world by sale or removal.” Virginia slaves did not want to be diffused.52

The more things changed in Virginia, the more they remained the same. After an interlude of security and laxity, Virginians again sprung into agitated alarm and action. In every county, the militia officers rediscovered that their men had neglected, lost, or sold most of their weapons since the last crisis. One colonel observed, “Should this alarm be well founded, we are in a helpless situation for want of arms.” So the local commanders plaintively begged the governor to send new arms and ammunition to their counties.53

The great fear of 1829 derived from the echo chamber of rumors, either wishful or terrifying, exchanged anxiously across the color line. One militia general regarded the talk in Northampton County as the very best proof of an impending race war: “I feel & see; every man here feels and sees that it is absolutely important to place the militia in a state to suppress Insurrection. It is heard from the lips of all. . . . Believe me, sir, the People of this shore are not easily agitated by danger & the present state of the public mind proves that we are in the midst of it.”54

In Virginia, nothing seemed more real and motivating than the fear of an internal enemy, for that dread shaped how delegates spoke and voted in the state convention as well as what militia officers and the governor wrote to one another. The pervasive alarm expressed a fundamental truth: that the exploitation of the slaves made them potential enemies. In Warwick County, Captain William Presson lamented “our Continual exposure to the hatred of those unfortunate & infatuated beings, a hatred existing from & consequent upon their relative situations in society.” Captain Presson did not suffer from the illusion that the slaves loved their masters. After the War of 1812, Virginians did indulge in new notions of happy and docile slaves, but the internal enemy never entirely vanished. Whenever trouble loomed, that haunting fear returned to grip the minds and words of Virginians.55

August 1 passed without the expected revolt, but the nagging dread lingered. In early September, Oliver Cross warned the Council of State, “That Virginia has an internal enemy none will deny I am sure. We have lately been seriously alarmed. We are always more or less alarmed & yet we are without the means of defence. . . . It behooves us all to be on the watch—to put ourselves in a situation to sustain that dreadful calamity. Come it will sooner or later.” The Virginians had woven themselves into a total system of beliefs and behavior enforced by their cultural convictions and material interests. That system sentenced them to a terrible and recurrent fear. Visiting Virginia, the English traveler Morris Birkbeck found that slavery was the “evil uppermost in every man’s thoughts; which all deplore, many were anxious to flee, but for which no man can devise a remedy.” Trapped within a system of their own making, they coped with its terrors by insisting that their greatest danger came from free blacks rather than from slaves.56

Where possible, slaves did conspire, but to escape rather than to murder. And they found their inspiration in the precedents set during the last war, rather than in some fantasy of Saint-Domingue. On the Atlantic side of the Eastern Shore counties of Accomack and Northampton, runaways revived the lessons of the war as learned in the slave quarters. Once again, they organized nocturnal escapes, obtained arms and boats, arranged leadership and sentinels, and fled to freedom. But this time they escaped to the northern states rather than to British warships. Northampton’s leading magistrate, John Eyre, reported that the white people were “much excited by the many evidences of discontent exhibited by our slaves & particularly by the elopement of several boat loads of them well provided with arms for their defence.”57

In adjoining Accomack County, the alarm revived another key player from the war: John G. Joynes. In 1813 and 1814 as a militia captain, Joynes had opposed slave escapes and battled British raiders, with Lieutenant James Scott as his great foil. Fifteen years later, Colonel Joynes commanded the Accomack militia. On August 10, 1829, he reported the “alarming extent to which the elopement of Slaves from this County to the states of New York and Pennsylvania has recently taken place, and the fact of their going off in gangs and armed, bidding defiance to the citizens.” Although a mass slave revolt did not erupt on August 1, there was a big escape from the Eastern Shore: “A boat’s crew eloped from the sea side in this County (which is now the usual mode adopted by them) and after proceeding some distance up the coast, they landed on an Island in the upper part of this county and established a regular camp and placed armed centinels out with orders to shoot down any white man who should approach within 15 yards of them. . . . This is only one of several cases that have taken place.” Seeking new arms from the state, Joynes implied that the runaways were better armed than the local militia, which suggests the destination for some of the lost, stolen, and sold guns from the last war.58

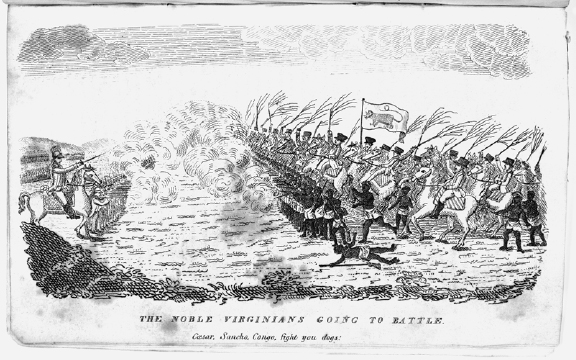

The Noble Virginians Going to Battle. In this crude engraving from 1820, a New England antislavery writer, William Hillhouse, mocks the Virginians as boastful cowards who forced their slaves to fight for them during the recent war. Produced during the peak of the Missouri crisis, the image conveys the New England Federalist attack on Virginia as weakened by slavery—a criticism that especially enraged Virginians. From Pocahontas: A Proclamation (1820). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society)

Nat Turner

In 1829, Oliver Cross had warned that a bloody slave revolt would come “sooner or later.” It came sooner, on the night of August 21–22, 1831, in Southampton County. A messianic preacher, Nat Turner, finally fulfilled a measure of the great Virginia nightmare: a midnight massacre of men, women, and children in their beds and cribs. The revolt fell short of the fantasy only in its small scale: Turner began with merely six men, and his force grew to sixty as they visited more farms to slaughter families, steal guns, and rally slaves. The rebels killed about sixty whites, most of them women and children. Turner sought to break through to the county seat, then known aptly enough as Jerusalem, to procure more arms before seeking a maroon haven in the Great Dismal Swamp. But his men were too few, their cohesion too weak, and their training with firearms too limited to resist the militia counterattacks during the next day.59

After routing the rebels, the patrollers massacred them, sometimes after inflicting brutal tortures. In the chaotic aftermath, spooked Virginians killed suspects who, in fact, had never had anything to do with Turner. In all, the Virginians butchered about 100 slaves, more than the total of sixty rebels. Indeed, most of the true rebels survived to stand trial. Turner and twenty-two others died on the gallows and the state sold and transported another twenty-one convicts. In retrospect, Turner’s exceptional revolt has served as a distorting prism for interpreting slave resistance in Virginia, for on no other occasion did that resistance involve indiscriminate murder.60

From Southampton County, the terror spread throughout the Tidewater and Piedmont and lingered into the fall. On October 4 in Nelson County, Joseph C. Cabell noted that “the white females in this neighbourhood can scarcely sleep at all in the night,” owing to the rampant rumors of slave uprisings. Three days later in Fluvanna County, John Hartwell Cocke marveled, “We hear of insurrections in every quarter of the State.” In the Northern Neck, a resident reported, “The blowing of a horn or the sight of a few unknown persons in company was quite sufficient to cause a neighborhood panic and call its undisciplined militia to arms.”61

In January 1832 in Virginia’s House of Delegates, the uprising shocked the representatives into breaking the public code of silence on slavery. Dismayed by the debate, William Goode insisted that violating the code courted disaster, for he deemed slaves “an active and intelligent class, watching and weighing every movement of the Legislature.” Discussion would raise their hopes, which when dashed would produce a massive revolt to “the destruction of the country.” Most of the legislators, however agreed to discuss Thomas Jefferson Randolph’s plan for a very gradual emancipation and deportation of Virginia’s slaves.62

Thirty-nine years old in 1832, Randolph was the son of Thomas Mann Randolph Jr., and the grandson of Thomas Jefferson. Radical only by Virginia standards, Randolph’s plan would free no living slave and, indeed, none save those born after July 3, 1840. Becoming state property, those children would be worked for Virginia’s profit until adulthood and then either sold farther south or shipped to Africa. Fearing for whites rather than feeling for blacks, Randolph primarily sought to whiten Virginia rather than to free slaves.63

After a long and frank debate, the legislators voted 73 to 58 against adopting any plan, no matter how slow, to abolish slavery. While the western delegates favored emancipation, virtually all of the Tidewater and Piedmont delegates wanted no further discussion of the troubling issue. Although “an evil, and a transcendent evil,” slavery had become inextricably woven into their society, economy, and culture. John Thompson Brown urged his fellow legislators to put up and shut up about slavery, which he deemed “our lot, our destiny—and whether, in truth, it be right or wrong—whether it be a blessing or a curse, the moment has never yet been, when it was possible to free ourselves from it.” Instead of acting against slavery, the legislators tightened their restrictions on slaves, making it illegal to teach any to read and write.64

In defeat, Thomas Jefferson Randolph anticipated a grim future for Virginia. Without emancipation, he expected that disunion and civil war “must come, sooner or later; and when it does come, border war follows it, as certain as the night follows the day.” Northern invaders would then rally “black troops, speaking the same language, of the same nation, burning with enthusiasm for the liberation of their race.” In that event, he warned Virginians that nothing could “save your wives and your children from destruction.”65

A veteran of the War of 1812 in Virginia, Randolph recognized the prowess of black troops when trained and organized by an invader with a professional military. A better prophet than a legislator, Randolph aptly predicted that during the next generation, the internal enemy would help to shatter slavery in Virginia, but they would wear the blue coats of the Union rather than the red coats of the British. During the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake, the British had never invested more than 4,000 troops, supplemented by 400 armed runaways, and that for only a few months in 1814. Such a limited force and brief incursion could rattle, but never topple, slavery. During the Civil War, however, the Union would invade the South for more than four years with more than a million men, over 180,000 of them African Americans who helped to destroy the slave system.66

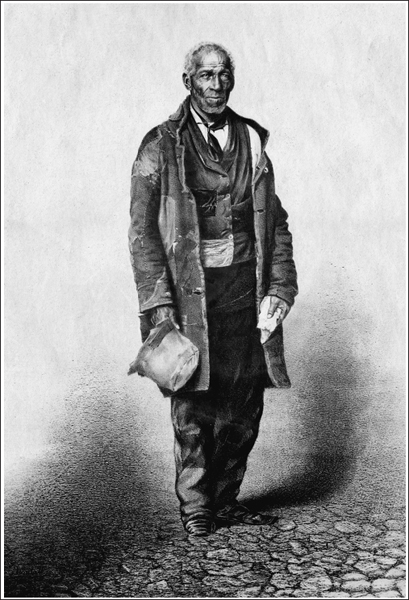

George R. Roberts, an undated photograph. A free black from Baltimore, Roberts served on American privateers during the War of 1812. Slaves sought freedom by escaping to, and fighting for, the British, but free blacks often served the United States by enlisting in the navy or on privateers. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society)