9

OF PLANS DEFERRED

The years 1864 to 1867. Family events and tragedies. Political and sectarian strife in New South Wales. The flood of ’64. Marriage of John Costello and Mary Scanlan and their departure for the north. Depression in Queensland. Patsy Durack makes preparations for the northward trek.

Incredible as it may sound after the experience they had just survived, both Grandfather and John Costello were resolved before they got back to Goulburn not only to return as soon as possible but to bring their families. Their heavy losses of stock and equipment were a bitter blow to family resources but they were somehow confident that when the current drought had broken they could soon retrieve their losses. Grandfather, for his part, was convinced that had they been able to continue in the direction of the flying birds they would have come upon good permanent water. Most of the surviving horses they had been forced to leave, running wild, below the border. Here, provided the blacks left them alone, it was thought they should do well enough until their return when they could have a grand horse muster and dispose of the increase for a small fortune.

Still, they had not reckoned on the barrage of family opposition that met their plan. Mrs Costello avowed that she and her husband would advance not a penny more on their son’s wildcat schemes. Tea-tree was a good property and there he must settle down. The three Scanlan brothers were behind her at this stage and refused to sanction young John’s marriage to their cherished only sister while he entertained the idea of returning with her to the desolate and lonely north. Grandfather’s position was complicated too, for the little daughter, Mary, born shortly before his return did not seem robust enough to survive an expedition of this kind. Family troubles crowded in on all sides. One of the little Skeahan boys had been fatally injured by a horse and another died of ‘a fever’ within a few weeks. Poor Mary had come home with her grief and her remaining two sons while Dinny, weary of battling on the drought-stricken selection he had been persuaded to take up near Lambing Flat, talked of defying the family and trying his luck in a deep shaft on the Adelong River.

About the same time news came from Sydney that the second sister, Margaret Bennet, had taken ill of ‘a chest complaint’ that had haunted the family since the famine years and Grandfather, in a frenzy of worry, went post-haste to fetch her home with her baby Mary Anne. As her husband’s work had kept him so much away, Margaret had lived with his relatives in the formal atmosphere of an English household where both her religion and her friendly, outspoken Irish ways were little understood. She had pined badly for the boisterous hugger-mugger of family life, for the riding, romping and banter, the bluster of Irish argument, and the intoxication of her brother Patsy’s quick enthusiasm for new schemes. It was thought that the dry inland air would soon restore her strength but she continued to decline as the weeks went by and the dress she had started to make for the Christmas races became her shroud when they crossed her hands on her rosary and braided her long fair hair for the last time.

There could be no prolonged wake in an Australian summer, but Irish families, determined to wring every ounce of emotion from ‘the tragedy’, came flocking from miles around with offerings of food and drink and blessed candles to burn beside the bier. The keening and the praying went on for a day and a night while the distracted husband pleaded with the family to turn ‘the barbarians’ away.

‘But it is as she would have expected it,’ Grandfather told him, ‘for if these are barbarians then so was she.’

Anxious to remove his child from this environment, John Bennet announced that he would take her to his own family, but Great-grandmother Bridget would have none of it.

‘And have her reared a Protestant!’ she exclaimed. ‘Over me own dead body!’

The Irishwoman, entrenched in her stronghold, won the first round of this classic and long-to-be-disputed issue, in which neither party could in conscience give way to the other. A host of well-meaning busybodies took up the cause on either side and Grandfather found himself embroiled in the only type of argument that was really anathema to him.

Already religion was at the bottom of most personal and political issues in the colony, the cause of frequent riots and fights. With every shipload of immigrants came a further influx of southern Irish, with a mingling of derelict and weak-willed falling easy prey to the temptations of the Free Selection Act. The prevalence of blackmail and perjury, the number of poor and disillusioned Irish now ‘dummying’ for big holders and turning farm-houses into grog shanties were used by political zealots in sweeping generalisations on the degeneracy of the Irish race and the iniquities of ‘papism’. The fine radical spirit of Ireland found itself in the ironical position of supporting the more moderately conservative leaders since the left-wing elements led by Henry Parkes and Dr John Dunmore Lang embodied a bitter hatred of their faith.

Parkes had emigrated from Birmingham a few years before the discovery of gold in New South Wales and through his support of the anti-transportation movement had won a reputation for vigorous leadership. Unfortunately for the Irish, however, he had grown up in an overcrowded industrial area where labour problems had been aggravated by an influx of hungry and dispossessed from across the channel. British workers in the inevitable fight for self-preservation stirred an ancient anti-papism into a living fire which many, like Parkes himself, carried with them to vent upon the Irish in the new land.

In the late fifties open conflict had broken out on the education issue, with Parkes espousing the State school system divorced from sectarian influence and the Irish keenly supporting a policy of education combined with religious instruction. For a few years all sects came in behind the vigorous campaign of Catholic and Anglican Churches, but in the face of bitter opposition Parkes, then Premier of New South Wales, established his first secular public schools in 1866.

Still the fight raged on, complicated by inter-sectarian prejudice and strife, disrupting the harmony of every community. It was now no mere land hunger that pulled Grandfather and Costello to the empty north but a wish to start afresh where they could find wholesome expression of true Irish life and personality.

The drought years broke in the winter of ’64 and the Mulwarrie came down in a mighty flood, drowning stock, sweeping through the settlements right into the streets of Goulburn. Life over the entire district was disorganised while families more fortunately situated took in the straggling bands of refugees. The house at Dixon’s Creek was filled to overflowing with friends and relations whose homes were temporarily under water.

Grandfather’s sister Bridget Scanlan had been giving birth to her third child while the water level rose steadily up the walls of their shack and big Pat stood by urging his wife to get up and swim for it.

‘I tell ye it’s drowned we’ll be, woman, if we stop here another mortal minute.’

Poor Bridget, helpless in her extremity, expostulated: ‘It’s not so much that I won’t get up as that I can’t, but if it’s scared you are there’s nothing to keep yourself.’

No sooner was the child born than Pat wrapped it in a blanket with its mother and swam them all to safety.

After the confusion and excitement of the flood came the marriage early in 1865 of Pat Scanlan’s sister Mary to John Costello, with Father MacAlroy, who had presided at so many of the family weddings, again officiating.

Mary Scanlan, the serene-looking girl from County Clare who had pioneered a selection with her brothers, was a fine rider, an efficient hand with stock and a crack shot with a rifle. She had besides the reputation of being ‘an authority’ on world affairs and local politics and contended that it was more important to know what was going on outside than to keep one’s eyes constantly bent on household tasks. Before the marriage Great-grandmother Costello thought such views unwomanly, and the bright, wide-spaced gaze and confidence with which Mary Scanlan would discuss the affairs of the day a sign of unseemly boldness. Later on, when Mary became her daughter-in-law and the mother of her grandchildren it was a different story and Mary’s virtues and intelligence were lauded to the skies.

No sooner were the couple married than the subject of the north country again raised its ugly head and the bride, far from shrinking from the prospect of such a pioneering adventure, urged it wholeheartedly. They were eager to make a start at their previous depot below the border and later expand into the new colony which was said still to be flourishing, albeit on borrowed money. It seemed a good sign that private investors were now following the example of the government which, with finance from London, continued its programme of public works and its wooing of immigration with glowing promises and advertisements in striking capitals:

WANTED: YOUNG MEN FOR QUEENSLAND!

For a time old Mr Michael Costello had done no more than vaguely shake his head over the ‘beautiful, lovely horses’ abandoned to their fate up north, but at last, no doubt under pressure from the young people, he quietly took action at the Lands Office. For a down-payment of £25 he obtained title to the lease of 32,000 acres between the Warrego and Paroo Rivers at that time occupied by a tribe of wild natives and a mob of near-brumby horses. He then wrote out a cheque for £3,000 to see his son on the road north with two hundred head of cattle, fifteen horses, two waggons, a dray, a bride, brother-in-law Jim Scanlan, two extra stockmen and a cook. Grandmother Costello was beside herself, berating in turns her husband, her son and any other relatives within earshot:

‘It’s soft in the head ye are, ye silly old man, and young John here with a heart of stone to be taking a young girl where there’s niver a white woman in a thousand miles and lucky to have a black gin attend her in her time of trouble. Well, ye can be off the lot of ye and good riddance and I’ll carry on at Tea-tree with a manager.’

Still when the time came for departure there was the senior Mrs Costello beside her husband in the family buggy, grim-faced under poke bonnet, the goose’s-head umbrella from which she was inseparable at hand to ward off the sun over the long, hot miles. Meanwhile Tea-tree had been put under lease, for the old people loved their home and could not bring themselves to dispose of it.

‘The day may come when you’ll be glad of our “little cocky run”, as ye call it,’ Mrs Costello said. ‘It will always be a roof over yere heads if ye’ve nowhere else to turn.’

John Costello and his wife would remember her words when, forty years later, an ageing couple with a big family, they would return to set up the neglected homestead and clear the land again of the encroaching scrub.

Eager as Grandfather was to follow them, family problems and financial difficulties tied him to the Goulburn district for a further two years. In July 1865 my father, Michael Patrick, was born but the joy of a son and heir was overshadowed by the sickness of the two-year-old girl. Grandfather, carrying her everywhere in his arms, crooning to her, willing her to life, scorned the women’s forebodings.

‘Wamen! It’s a flock of ravens they are. The same they were saying of Sarah—“Ah, the little angel not long for this world” and all. God Almighty, look at her now, with her brood of giants!’

Sarah Tully felt no less cramped than himself under the conditions of close settlement. At twenty-five, a small, lean, brown-skinned woman, she had a forceful, almost terrible vitality and sometimes out of frustration or Irish indignation at some local incident, she would saddle up and ride like the devil across country to fling herself off, breathless and excited, at the gate of Dixon’s Creek some fifteen miles away. Great-grandmother Bridget would come panting, full of joy and anxiety:

‘Sarah child, ye’ll have the bairn born dead if ye ride like that!’ (There was mostly a babe in arms and another on the way.)

‘Nonsense, Mother! Haven’t I ridden with them all, and aren’t they the finest children in the colony?’

The fierce devotion that Sarah lavished on all her family was almost fanatic with her offspring whom, following the example of her Grandmother Mammie Amy Forde in Ireland, she placed, soon after birth, on the fresh tilled soil to receive the goodness and strength of their mother earth. For all this two of her little ones already lay near her father and Poor Mary’s two sons in the Goulburn cemetery.

‘Please God we can all be going north soon,’ she would say. ‘Even Dinny Skeahan should be doing all right up there away from the gold and the pubs.’

By ’66, however, Grandfather could no longer close his eyes to the fact that Queensland’s rosy promise had grown somewhat pale. That the colony’s debentures had become a drag on the London market by the middle of ’65 had been considered of little account. ‘Only to be expected,’ men said, ‘a temporary fluctuation’, and in this frame of mind the government had plunged on with its ambitious schemes of development. But British investors had become wary of what they now knew from bitter experience in the defeated American Confederacy, in South American republics, in Spain and the Middle East, to be dangerous over-borrowing. The failure, in the middle of ’66, of London banks that had made big advances to the new colony reflected at once on its affairs. There was chaos within a day of the news reaching Queensland. Unemployed and disillusioned rioted in the streets of Brisbane and bankruptcy spread like a bushfire through the Land of Promise.

Meanwhile, in the north of New South Wales, always at least three months out of touch with current affairs, the Costellos were fighting for foothold in an inhospitable land. Their station, which they had named Warroo Springs, gave little sense of security for the country was patchy from a pastoral point of view, and the blacks who had soon discovered the superiority of horseflesh to their native lizards and kangaroos were a constant menace to stock. John Costello had decided on a policy of killing beasts for them at regular intervals and of trying to explain the white man’s views on personal property, but one of their young stockmen made a game of firing over the natives’ heads for the fun of seeing their terrified retreat. One day he had been found speared in his swag some miles from the homestead, since when no natives had shown up for their beef ration but had increased their killing and chasing of stock on the run. Nonetheless, a few natives had attached themselves to the white settlers and were proving faithful helpers.

Not long after the family’s arrival at Warroo Springs a son, John, had been delivered to the young couple by the capable hands of Great-grandmother Costello, and the infant’s sturdy build seemed a good advertisement for the district. In letters to his relatives John Costello was careful always to temper news of their hardships and misfortunes with a note of optimism for the future and reports of ‘the better country farther out’ to which they would move as soon as other members of the family had joined them.

Early in ’67, soon after the birth of a second son to my grandparents, their little girl’s frail life ended. Consumed with grief—for how could there ever be such another angel child?—Grandfather determined to delay his departure no longer than it might take him to ‘raise the wind’. The sale of their three Argyle district properties, about 900 acres in all for which they had paid £1 an acre, would not realise much more than twice the purchase price, even allowing for improvements, since their stock had been depleted since the ’63 debacle and the best they had left was to go on the road with them. Grandfather estimated that he must have at least £4,000 behind him for this project, about £2,000 to see them on the road and as much again to tide over the first two or three years when little would be coming in and a good deal going out.

Bankers, hitherto fairly co-operative in advancing money to settlers, hesitated to finance a venture to a still unknown destination in an already depressed colony where the settlers had, moreover, only a flimsy lease title to the land. The problem was overcome at last by a deal of Irish juggling and the advice and assistance of the bankers Samuel Emanuel and his son Solomon who had recently joined his father in Goulburn. So, after fourteen years in Australia, Grandfather started on his thousand-mile trek north with a load of debt that would have bowed the shoulders of any but an incurable optimist.

Although this time he could afford only a small herd of breeding cattle and comparatively few horses, he had refused to stint on equipment. They had come into the district as penniless immigrants but at least they should move out in the grand manner, and Grandfather proudly displayed to curious droves of friends and relations the wonders of his four covered waggons, built to his own design, two with bunks that could be folded when not in use and complete with everything required for comfort on the road, the others stacked with goods, equipment and livestock. Everything they possessed was to go with them, even their fine Irish linen and lace, bulky feather mattresses, silver and brass, china and glassware, for this time there could be no turning back.

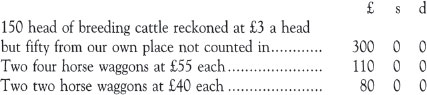

A rough estimate of their requirements and expenses for the expedition ran as follows:

Buggy and buggy horses, furniture, crockery, cutlery, household linen, kitchen sundries, a number of tools, saddling and gear, 6 pigs, 6 milking goats, 14 laying hens, 3 roosters, 12 Muscovy ducks and 3 sows and boar and other sundries, not counted in exes, as already to hand.

Farewells went on amid final preparations for departure, Grandfather extending wholesale invitations to friends and relatives to join them later in Queensland. Already he was picturing a Beulah land of happy community life, roads and townships springing up in the empty wilderness. A simple-hearted man with a passion for ‘fixing’, Grandfather believed that life not only should but could be adjusted so that people were not constantly harassed and frustrated, where families could put down roots and spread thriving branches.

Any dismay Grandmother might have felt for this exodus was tempered by pleasure at the prospect of joining her parents and her brother John. It was true, as her mother maintained, that she was not like her brother’s wife, Mary Costello, by nature or inclination a pioneer. She would have settled down very happily to an ordinary suburban life and if circumstances drew from her qualities of resource and endurance that made her seem born to the role, she at least had no such illusions. Once, when praised by a city friend for her courageous pioneering spirit, she replied simply:

‘I had nothing of the sort, my dear, but when Patsy said we must go pioneering what else was I to do?’

While their relatives were packing up for Queensland, Darby Durack and his family were also moving out from Dixon’s Creek to what they considered superior land near Boorowa, about sixty miles west of Goulburn. Now the parents of seven sons and five daughters, Darby and his wife, anxious that the younger children should have a better education than had been possible for the rest, did not aspire so far afield as their relatives. The two eldest boys, ‘Big Johnnie’ and ‘Black Pat’, as they were usually known for obvious reasons of identification, were now seventeen and fifteen years old and had already been on droving trips with their Uncle Tom Kilfoyle. Already men in size and practical experience, they were now determined to strike out for themselves on the Castlereagh where they had taken up two sheep selections which they called Gidyeagunbine and Muchenba.

‘The old man will get nowhere with his scrub-bashing,’ they declared. ‘The only way to get anywhere in this country is leave the land as it is and run your stock on the natural pasture.’

The Irish farmer who had worked and cherished his land almost as a sacred trust had been unable to influence the outlook of his Australian-born sons.

‘Ye must learn to know the land,’ he had said. ‘Ye must feel for it as a living thing or it will die.’

But his boys had shrugged:

‘Better that than it should kill us first.’

Since Great-grandmother Bridget had promised her son-in-law John Bennet that she would not trail his little girl to Queensland, she now made her home with Darby’s family at Boorowa. Her youngest boy—‘Galway Jerry’ as he was later called—was to remain with her and go to school for another year or two before joining his elder brothers, and the youngest daughter, Anne, to continue teaching in Goulburn where she was being ardently courted by a young Irishman named John Redgrave who gave his occupation as ‘miner, horsebreaker and tutor’.

Sarah Tully had been all for joining the north-bound expedition but here her quiet-spoken husband exerted his authority. Without capital behind them another couple and five children would be nothing but a burden to poor Patsy. They must wait and see how things turned out before giving up their interests in the south. Pat had recently taken up a second free selection block near Adelong, about 150 miles south-west of Goulburn, a haunt of his early mining days where, since there had been fresh rumours of gold in deeper shafts, he dreamed of dropping on a lucky strike while tilling the land. Sarah, always suspicious of mining, said they would move from their place at Hume Creek only to go north, but Dinny Skeahan had happily agreed to fulfil the conditions of occupation by putting up a shanty on the Adelong block and working a shaft

Poor Mary, still vulnerable to the bright plans her husband so eloquently expounded, agreed to carry on the selection at Lambing Flat with her little sons while Dinny dug up enough gold to put them all on the road to Queensland. To these complicated plans Sarah vented her scepticism in the words of a popular song of the time:

So he built him an iligant pigstye

That made all the Munster boys stare,

And he builded likewise many castles

But alas! they were all in the air.