CHAPTER 1

In The Trip Across Paris, a film by Claude Autant-Lara from 1956, Jean Gabin and Bourvil walk through the night of the Occupation, made darker than usual by air-raid precautions that have put out the street lamps and covered the windows with blackout paper. The two rogues, carrying heavy suitcases filled with pork, proceed from the Rue Poliveau to the Rue Lepic – from the Jardin des Plantes to Montmartre. This was a very famous film in my youth, and even today Gabin’s ‘Poor bastards!’ has the ring of a popular phrase. The story may well have inspired my title for this book, and perhaps the entire project, even if it has nothing in common with the adventures of Gabin and Bourvil, in which encounters with policemen in cycle capes, black-market traffickers, German patrols and ladies of the night, all to the sound of sirens, are comic episodes whose backdrops make Paris the setting of a night-time dream.

My own path is rather a daytime one, with a different orientation: from Ivry to Saint-Denis, more or less following the dividing line between the east and west of Paris, or what you could call the Paris meridian. I chose this itinerary without much consideration, but later on it became clear to me that it was no accident, that this line followed the meanders of an existence begun close to the Luxembourg garden, led for a long time opposite the Observatoire, and continued further to the east, in Belleville, at the time I am writing, but with long spells in the meantime in Barbès and on the north side of the Montmartre hill. And in fact, under the effect of the peerless mental exercise that is walking, memories have risen to the surface street by street, even very distant fragments of the past on the border of forgetfulness.

If this journey begins at Ivry it is because of a bookstore. Envie de Lire is not simply a shop that sells books, it is also a place of browsing and discovery. The piles of books, often unstable, are not arranged by chance, but linked by a thread that takes a moment to discern. Perhaps you won’t find the title you’ve come to look for, but no matter, you will leave carrying a book of photography or philosophy, a Mexican novel or the memoirs of a forgotten revolutionary. These small premises on the Rue Gabriel-Péri are propitious for discussion, even argument. Readings from new books finish late, and groups on the pavement are in no hurry to disperse as the staff finally bring in the boxes of books open to all under the arcade. The business is a cooperative, so does not have an owner; but R., solidly built as Spaniards can be, is both the soul of the place and the representative of an endangered species, that of poetic communists.

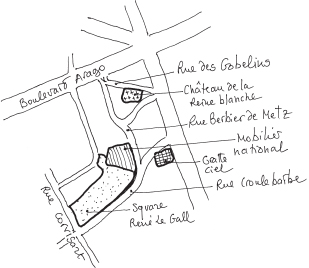

Another reason for choosing Ivry as my starting point is its remarkable town centre, in which Envie de Lire is a lively presence. This is an architectural ensemble unlike anything familiar. Emerging from the Métro and looking upward, you are struck by a tangle of points, sharp corners, irregular polygons, gangways and planted terraces, all in raw concrete. Small apartment blocks, all designed to be slightly different, are linked by direct contact or by a network of stairways and overhead passages, creating a three-dimensional labyrinth. Enclosed in the general tangle, half a dozen small towers punctuate a landscape whose grey concrete is softened by the overflowing green of the planted terraces.

The architects, Renée Gailhoustet and Jean Renaudie, took thirty years to build this ensemble, from the early 1960s to the late 1980s, at a time when, in the name of town-planning, the banlieue was falling victim both to ‘zoning’ – different activities pigeonholed into distinct zones – and to high-rise blocks and concrete slabs. Their aim, on the contrary, was to superimpose functions, mixing together shops, services, artists’ studios, crèches, schools, offices and housing, in an attempt at collective living made possible by the support of the communist municipality. Renée Gailhoustet herself lives in the quarter that she built. From her terrace planted with fruit trees, she shows me how, by way of these staggered spaces, superimposed and almost attached, connections are established between the tenants. She tells me how she designed the tower apartments to create duplexes with two aspects, and all the tricks she came up with to make this social housing as pleasant as that of the rich.

The exit from the Mairie-d’Ivry station opens onto a noisy avenue widened into a square. This does not continue eastward, towards the Paris cemetery and Villejuif, being blocked by a hill with a small medieval church on its summit and, behind it, a rural cemetery just a hundred metres from the flow of cars. Traffic is routed towards Paris on a road that bears the name of Ivry’s great man, Maurice Thorez. This is bordered with shacks, workshops, garages, small factories, low-rise apartment blocks – a landscape you cross without really looking at it, though not lacking in charm. From time to time, you have a view of lower Ivry and the Seine, marked out by the smoke from urban chimneys and the concrete spire indicating the red high-rise of the Cité Maurice-Thorez.

My view of Thorez is mixed. A docile executor of Stalin’s policy, champion of productivism in the wake of Liberation, organizer of Moscow trials in Paris, and a thoroughly detestable character. But despite everything, despite himself, his name remains bound to the memory of a time when, for masses of young people of whom I was one, communism had nothing to do with the terrible system that repressed Eastern Europe. It was a world in which fraternal relations were forged by way of meetings, demonstrations, actions conducted joyfully in common, not to mention holidays. I owe a great debt to my communist comrades at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand and then the PCB (physics, chemistry, biology) preparatory year for medical studies, held in a brick building opposite the entrance to the Jardin des Plantes alongside Cuvier’s house. It was due to them that I broke with the world for which, as the son of a good bourgeois family of assimilated Jews, everything marked me out – broke definitively, even if the professions I went on to practise, surgery and publishing, do not count among the most proletarian. Despite the likes of Garaudy, Kanapa and Thorez, I do not believe it right to treat everything concerning the communism of those years as ‘Stalinist’, nor to deny my own part in this. If truth be told, I am even rather proud of it.

Ivry, Avenue Maurice-Thorez.

At the Porte d’Ivry as elsewhere, the meeting point between banlieue and city is neither gentle nor pleasant. In 1860, when Paris annexed the immediately surrounding communes to complete its twenty arrondissements, the connection was formed quite naturally. Passing today from the Rue du Faubourg-du-Temple to the Rue de Belleville, you do not have the impression of crossing an obstacle, despite passing the site of a former city gate, the Belleville barrière in the Wall of the Farmers-General. Sometimes the transition is a little more awkward, as between the Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière and the Rue des Poissonniers across the complicated Barbès intersection, or between the Avenue des Gobelins and the Avenue d’Italie across the Place d’Italie, but there is no real problem here.

Between the city of Paris and the outlying communes, however, things are quite different, particularly to the north and east, where crossing from Paris to the banlieue on foot may be quite an adventure. At the Porte des Lilas, despite the Périphérique being underground, you have to cross a great void between the last social housing blocks of the Boulevard Mortier and the first old houses of the Rue de Paris in Les Lilas, with a tiny green space to the left (the Serge-Gainsbourg garden which, according to a notice, is an example of ‘urban continuity’ – a fine denial of reality) and a cinema on the right – a gigantic black blockhouse next to a bus station. At the Porte de Pantin, after having left the Avenue Jean-Jaurès bordered on one side by a Hôtel Mercure and on the other by Jean Nouvel’s frightful Philharmonie, you find yourself in a no man’s land, passing beneath the Périphérique, crossing the slip roads and tram lines, bypassing an inaccessible green space planted with grass and little Christmas trees. This path is still possible without danger, but further on, at the Porte de la Chapelle, the landscape is indescribable: the Périphérique, the bridge where the railway from the Gare de l’Est meets that from the Gare du Nord, and the ramps of the A1 and A3 motorways together form such an obstacle that it is a rare bird who risks crossing on foot from the Rue de la Chapelle to Saint-Denis.

At the Porte d’Ivry where I stopped for a moment, the traffic flow is much weaker, and the dominant impression is not chaos but concrete housing. The poor but dignified buildings of the Avenue Maurice-Thorez open onto the Place Jean-Ferrat, a large square whose centre is marked by a tired larch tree (according to the notice, a liberty tree planted for the centenary of 1789). The right-hand side of the place still contains down-market shops – halal butcher, pizzeria, Lycamobile – while on the left, at the foot of the twenty-storey towers, life insurance and white goods are signs of modernity. To the Paris side, the place is bordered by the Périphérique. On the corner, a large building of concrete and faux brick triumphantly bears the omnipresent syntagm ‘BNP Paribas’. It is not enough for this banking establishment to have disfigured the Maison Dorée on the Boulevard des Italiens, a masterpiece of romantic architecture, or to have made countless Paris crossroads ugly with its greenish premises – it also has to impose itself in the banlieue, as here or at the Grands Moulins de Pantin, where it subjects a landscape worthy of Doisneau to its icy profitability.

Between the Périphérique and the Boulevard des Maréchaux, which bears here the name of Masséna, you cross the ZAC Bédier.1 How did the respected medievalist Joseph Bédier come to be enlisted for this purpose? His name only appears on a tiny street, off the Place du Docteur-Yersin – the disciple of Pasteur who discovered the plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis – another trace of medieval Paris. The pride of the ZAC is an immense office building on the Avenue de la Porte-d’Ivry. The signboard indicates that its architects are J.-M. Ibos and M. Vitart, former students and associates of Nouvel, known for creations that bear the same mark as their teacher, a concern for the façade. In this case, as represented on the signboard, the façade will have a uniform repetition of tall and narrow openings. This ZAC once again misses the opportunity for a harmonious junction between centre and periphery by way of a carefully woven urban fabric.

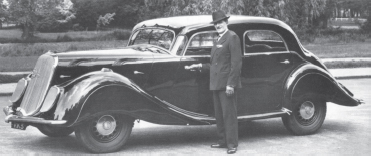

On the Boulevard Masséna, at the corner between the Avenue d’Ivry and the Rue Nationale, I discover a kind of relic, the former Panhard & Levassor works. The essentials of this three-level structure have been preserved, solid stone below and brick on the two upper floors. A plaque indicates: ‘Here the automobile industry was born in 1891.’ These are the walls from which so many marvels emerged, such as the large Dynamic saloon of 1937, with its headlights protected by a grille, three seats in front and the steering wheel in the middle. Or the little Dyna whose engine made a strange noise like a saucepan cooking, but which won the prize at Le Mans each year for its ‘performance’. During the First World War, Panhard & Levassor, like Citroën and Renault, employed workers brought from Indochina, or recruited in China, to replace Frenchmen sent to the front. This is said to be the origin of the Chinese quarter in the 13th arrondissement, which grew in the 1970s with the arrival of the ‘boat people’.

La Dynamic Panhard-Levassor, 1937.

The Avenue d’Ivry runs along the eastern side of this Chinatown, which continues across the Dalle des Olympiades. It is less busy than the neighbouring Avenue de Choisy, but there are several red and gold restaurants, and Chinese supermarkets in front of which old women sell bunches of aromatic herbs on upturned crates. It ends at the junction with the Rue de Tolbiac, the segment of a long ring road which leaves the Seine at the Pont de Tolbiac and returns at the Pont Mirabeau – or, if you prefer, from Léo Malet to Guillaume Apollinaire. Its aim was to link and open up the communes annexed in 1860 – Ivry, Gentilly, Montrouge, Vanves, Vaugirard and Grenelle. It bears the names of forgotten battles, not all of which are reliably attested: Tolbiac (victory of Clovis over the Alamans), Alésia (Vercingetorix’s defence against Caesar’s siege), Vouillé (victory of the Franks over the Visigoths). The municipal authorities of the 1860s probably intended to assert the Gallic and Frank origins of the country (only later, under the Third Republic, was the final segment of the road named Rue de la Convention). If it works perfectly well for traffic, it has not encouraged notable urban developments: along these streets there is little life, little that is picturesque; you just drive. Which is also true for its counterpart on the Right Bank: the Avenue Simon-Bolivar, the Rue des Pyrénées, the Avenue du Général-Michel-Bizot.

On the Rue de Tolbiac, a few metres from the crossroads with the Avenue d’Ivry and the Avenue de Choisy, a building in 1950s style houses the Archives d’Architecture du XXe Siècle. Fifty years ago this was the Marie-Lannelongue surgical unit, where I conducted experimental work on coronary arteries in a laboratory headed by the gruff but charming Michel Weiss, the only person to have trusted me when I maintained that it was possible to operate on blood vessels no thicker than a matchstick or two. I have a pleasant memory of nights spent watching the laboratory dogs, and discussing the state of the world with Weiss and the lab assistant, who was also named Michel. No one, or hardly anyone, believed that this experimental work could have clinical applications, but today operations of this kind are carried out every day at dozens of centres in France, and thousands across the world.

A little way on from this crossroads, the Avenue de Choisy opens to the right onto a haven: the large Square de Choisy, almost a real park, which dates from the Exposition Internationale of 1937. A fine brick building from the same period stands on one side of the garden: the Fondation Eastman, a dental care centre founded by George Eastman, the American philanthropist who invented both celluloid photographic film and the first portable camera, the Kodak (‘press the button, we do the rest’). The fact that Kodak could go bankrupt and end up being bought out by a Taiwanese businessman is as amazing as the collapse of General Motors.

The garden is designed in the French style, with a grace created by a harmony of proportions between a body of water, wide lawns, and double rows of linden trees. In the 1980s it was home to a sculpture by Richard Serra, ‘Clara Clara’, consisting of two large curved plates of weathering steel that the spectator could walk between. It seems that this is to be brought out of storage and placed near Nouvel’s Philharmonie, where a little beauty would not go amiss.

At the end of the Avenue de Choisy I reach the Place d’Italie, where the counterpoint to the flat façade of the town hall of the 13th arrondissement is a building by Kenzo Tange, the Grand Écran, today known as Italie Deux. Tange was a good architect in the 1960s; but here, this immense concave curtain wall, topped by a Meccano campanile lift, adds nothing to his fame. The place itself is a major traffic roundabout. Its central reservation is deserted, since only daring sprinters could reach it. It was in crossing the Place d’Italie that Giacometti was knocked down by a car and left with a limp for the rest of his life. The reservation is planted with Paulownias, as Ernst Jünger, a botanist among other things, mentions in his Journal de guerre. On 5 May 1943, Jünger passed here en route for the Eastman centre, to get treatment for his teeth: ‘All these Paulownias on the Place d’Italie: an impression of precious aromatic oil burning on enchanted candelabras.’2 The blue flowers of these candelabras are not enough to add charm to the Place d’Italie, which has even less of it than the Place de la Nation, another great roundabout along the Wall of the Farmers-General, but whose central reservation boasts Dalou’s magnificent ‘Triumph of the Republic’. The municipal authorities preferred the fat lady by the Morice brothers, which contributes to the ugliness of the Place de la République today. At the time Dalou was under a cloud. He had been a member of the artists’ commission during the Commune, still an unpardonable offence in the 1880s. Later on he would sculpt other marvels in Paris, such as the pediment of the Grands Magasins Dufayel on the Rue de Clignancourt, the monument to Delacroix in the Luxembourg, and the recumbent figure on Blanqui’s tomb in Père-Lachaise.

© Cléo Marelli

Dalou’s recumbent figure of Blanqui in Père-Lachaise.

During the June Days of 1848, the site of the present Place d’Italie saw one of the most controversial events in this great insurrection of the Paris proletariat, who took up arms against the threat of being sent to Algeria as agricultural workers, or to the Sologne to drain the marshes. The barrière here was part of the Wall of the Farmers-General, which followed the present course of the Boulevard de l’Hôpital on one side and that of the Boulevard Blanqui on the other. Situated in the middle of the present place, this barrière, designed like the other fifty-two gates in the Wall by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, was made up of two pavilions whose arched façades faced each other in perfect symmetry, with the customs offices between them.

This is where the misfortunes of General Bréa began on 25 June, the third day of the battle. Having seized half of Paris in the first couple of days, the insurgents were now in full retreat, routed even on the Left Bank where they were chased by artillery fire from the Latin Quarter, the Panthéon, the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève and the Faubourg Saint-Marceau. Withdrawing to the barrière, several hundred insurgents took up position behind a barricade erected between the two pavilions. General Bréa reached the barrière at the head of a column of 2,000 men, and proposed to negotiate. The accounts are so discordant that it will never be possible to decide whether this was a ruse of war or came from a real concern not to add to the bloodshed. What is certain is that Bréa entered the insurgent camp and did not come out alive. He was killed along with his aide de camp in a house on the Route de Fontainebleau (today the Avenue d’Italie), on the Maison-Blanche side. Twenty-six supposed authors of this ‘abominable infamy’ were tried by a military court in January 1849. Most were given long prison sentences, and two of them, Daix and Lahr, condemned to death. For their execution, the guillotine was erected close to the Barrière d’Italie, surrounded by thousands of soldiers and twelve cannon.

In the history of 1848 in France, the June Days hold a singular and even paradoxical place. Tocqueville himself, who participated on the side of order, bears witness to the gigantism of the event:

This June insurrection, the greatest and the strangest that had ever taken place in our history, or perhaps in that of any other nation: the greatest because for four days more than a hundred thousand men took part in it, and there were five generals killed; the strangest, because the insurgents were fighting without a battle cry, leaders, or flag, and yet they showed wonderful powers of coordination and a military expertise that astonished the most experienced officers.3

Yet this black moment remains little explored: the last monograph devoted to it dates from 1880. The fact is that no brilliant figure emerges from the crowd of anonymous workers who took up arms on 23 June. Whereas the Commune of 1871 had Vallès and Courbet, Louise Michel, Élisabeth Dmitrieff, Eugène Varlin and so many others, the insurrection of June 1848 offers no individual, nor any narrative, for the imagination to hold on to. We should therefore remember the names, and honour the memory, of those who were brought before the council of war for the Bréa affair: Daix, a day labourer; Guillaume Pierre, known as Barbiche, a thresher; Coutant, a cooper; Beaude, a cobbler; Monis, a sausage-maker; Goué, foreman in a tannery; Paris, a horse dealer; Quintin, a builder’s apprentice; Lebelleguy, a cotton-spinner; Naudin, a day labourer; Luc, an employee of the highways department; Moussel, a dock worker; Vappreaux the elder, a horse dealer; Vappreaux the younger, the same; Lahr, a builder; Nourrit, an upholsterer; Bussière, a jeweller, Chopart, a bookshop employee; and Nuens, a clockmaker.4