CHAPTER 3

For a long while, I would make a detour in order to avoid the Luxembourg garden, too marked in my memory by Sunday afternoons when I was sent out to ‘get some fresh air’ – my mother had the hygienic ideas of her time. Once cured, I learned to love this garden, its two parts separated by a virtual line that follows the Paris meridian, across the fountain in the central pond and past the Senate clock. To the east, the Saint-Michel side, is the young Luxembourg: students and schoolchildren, young foreigners enjoying themselves, sandwiches on the benches and limbs bronzing in the first spring sun. To the west, the Montparnasse side, around the tennis courts, the children’s play area and the beekeeping pavilion, is a calmer and less busy Luxembourg: bourgeois from the Rue Guynemer, psychoanalysts and foreign diplomats, swarthy nursemaids in charge of blond children. On this side, along a path with immense plane trees surrounded by water, Dalou’s monument to Delacroix shows how, starting from an agreed programme (allegorical figures around a plinth supporting a bust), constraint can give rise to a masterpiece.

It was on a deserted path in the Luxembourg garden that Marius met Cosette and Jean Valjean for the first time, ‘a man and a quite young girl sitting almost side by side on the same bench, at the most solitary end of the path, by the Rue de l’Ouest [now d’Assas]’. Nerval depicts a similar meeting in his Odellete, titled ‘An Alley in the Luxembourg’:

Verlaine, Cendras, Rilke, Léautaud, Sartre, Faulkner, Echenoz… Few places in Paris have inspired so many writers and poets, not to mention cineastes – Jean-Luc Godard’s joyous All the Boys are Named Patrick, or Louis Malle’s darker The Fire Within.

Emerging from the Luxembourg, I pass behind the Odéon theatre. I believe there were still booksellers under these arcades in the early postwar years, but nothing comparable with the time when Courteline, Marcel Schwob, Catulle Mendès or Barrès hung about here to see how their books were selling, according to Léon Daudet in Paris vécu.1

The corner of Rue de Condé and Rue de Tournon is broken off, creating a space badly filled by a little garden and a newspaper kiosk. At one time this was the site of Foyot, a famous restaurant, popular with the members of the nearby Senate. In 1893, at the time of ‘propaganda of the deed’, an anarchist bomb blew up the restaurant – though this was hardly a success, as not only was no senator present, but a sympathizer with their cause, Laurent Tailhade, happened to be dining there and lost an eye. Some believe that the bomb was planted by Félix Fénéon himself, the best critic of his time (so said Mallarmé), and later editorial secretary of La Revue blanche. This is by no means certain, but Fénéon was among the accused in the famous ‘trial of the Thirty’ in August 1894: detonators had been found in the office of the war ministry where he was chief clerk. The charge here was ‘association with malefactors’, but the lois scél&teau. The central pavilions#x00E9;rates of 1893, though making defence of terrorism a criminal offence, had not provided for special anti-terrorist courts, and the jury found all the defendants not guilty.

The Rue de Tournon is for me one of the loveliest in Paris, for the buildings it contains but above all for its bell shape, the way that its two sides diverge after the Rue Saint-Sulpice to frame the central pavilion of the Luxembourg palace in a proud scenic arrangement. This was in no way accidental. When the Comte de Provence, brother of Louis XVI and future Louis XVIII, divided up the land that he owned here, the men who designed this quarter in the 1780s paid the site great attention. Proof of this is the two opposing triangles, one with its point at the Odéon theatre and its sides on Rue Crébillion and Rue Casimir-Delavigne, the other with its point at the Odéon crossroads and its sides on Rue Monsieur-le-Prince and Rue de Condé. The common side of these triangles is Rue d’Odéon, the first street in Paris to have been bordered with sidewalks. The ensemble is drawn with a flexible asymmetry that tempers its rigour and makes walking a joy.

For the Luxembourg palace, the Florentine Marie de Médicis wanted a building inspired by the Palazzo Pitti. She entrusted its execution to Salomon de Brosse, who, as a good Protestant, had his own ideas. While reproducing formal details of the Florentine palace – the bosses and the ringed Tuscan columns – he built a French-style château. The central pavilion has a grace due largely to its imperfections, the hesitations perceptible in its details, its transgressions of the rules. Just as the awkwardness of adolescents may be more touching than full-blown beauty, so architectural gaucheness is often more attractive than classical constructions. The time when the Luxembourg was built, around 1610, was an uncertain period in architectural terms, when Gothic had not yet completely disappeared in Paris (the Gothic church of Saint-Eustache was completed under Louis XVIII), when the Renaissance still remained discrete, and the Baroque had not successfully established itself. Hence the imperfect and charming architecture of the façade of Saint-Gervais, by the same Salomon de Brosse, or the dome of Saint-Paul seen from the Rue Charlemagne.

In the Rue de Tournon, several plaques remind us of illustrious former residents. One plaque, above the Café Tournon, informs us of the final years spent there by Joseph Roth, who drowned the chagrin of exile in alcohol. The two sides of the street are symmetrical in line, but different in physiognomy. On the right, as you go downhill, you have a homogeneous set of buildings from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with the majority of shops now devoted to luxury clothing. The left side is a succession of noble neoclassical hôtels. One of these, at no. 10, was transformed into a barracks and served as a major slaughterhouse for prisoners during the June Days of 1848. Leibniz stayed in an annex to this hôtel when he lived in Paris in the 1670s and invented the infinitesimal calculus.

A dog’s-leg via the Rue Saint-Sulpice leads to the start of the Rue de l’Odéon, where nothing, no plaque or souvenir, recalls that these few metres were a great centre of world literature in the interwar years. At no. 7, Adrienne Monnier opened a lending library in 1915 under the sign La Maison des Amis des Livres. Almost opposite, at no. 12, her partner Sylvia Beach founded a bookshop on the same principles in 1921, Shakespeare and Company.2 The list of women and men who frequented these enchanted premises is too long to be given completely here. We may just mention, for Adrienne Monnier’s shop, André Gide and Paul Valéry, Henri Michaux, Aragon, Michel Leiris, Valéry Larbaud, Léon-Paul Fargue, Saint-John Perse, Walter Benjamin, Italo Svevo… While on the other side, at Sylvia Beach’s, you could come across Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Djuna Barnes, Ezra Pound or James Joyce, whose Ulysses Sylvia published in 1922, at a time when the book had been banned in the United States, Great Britain and Ireland. This short stretch of street bears the memory of an unexampled adventure in literary history, and all book-lovers should make a little mental salute when they pass by.

To find the Paris of the Great Revolution in today’s city takes a good deal of imagination. The most famous sites have been destroyed, and the most glorious names are largely absent. The noisy Odéon crossroads, for example, offers only few vestiges to remind us that it was the main centre of the Revolution on the Left Bank.

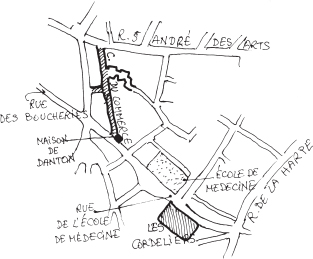

The topography here was greatly transformed by the cutting of the Boulevard Saint-Germain. At the time of the Revolution, a narrow roadway, Rue des Boucheries, closely followed the line of the present boulevard before continuing directly via the Rue de l’École-de-Médicine. The Cour du Commerce, today amputated by the boulevard, was much longer, extending from the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts as far as the Rue de l’École-de-Médicine.

Just as the Société des Amis de la Constitution took its name from its premises in the Jacobins monastery, so the Société des Amis des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen became the Cordeliers club once it had settled in the monastery of that order, almost opposite the colonnade of the École de Médicine. But the symmetry stops there. At the Cordeliers, recruitment, attendance and operation were more plebeian than at the Jacobins. The entrance fee was symbolic, anyone wishing to join could do so, women were allowed to speak, and the main orators were neither advocates nor any kind of lawyer, but laymen who came from the theatre (Hébert), printing (Momoro) or medicine (Chaumette). Danton often came to the Cordeliers, but the club’s hero was Marat. After his assassination, his heart, placed in an urn, was suspended from the ceiling of the meeting room at a solemn ceremony.

The Cordeliers are rather poorly viewed by historians of all stripes: vulgar bawlers with no clear political vision, always ready for untimely insurrections. Yet they were the first to demand the dismissal of the king after the flight to Varennes, to organize the revolution of 10 August 1792 that put an end to the monarchy, and to launch the great campaign of de-Christianization in the autumn of year II, which saw all Paris churches closed for worship. This was where the sans-culottes of the faubourgs and popular quarters came to discuss and debate. The only writer to do them justice was Gustave Tridon, Blanqui’s right arm:

Hail to you, Hébert and Pache, pure and noble citizens; Chaumette, whom the people loved as a father; Momoro, an ardent pen and generous spirit; Ronsin, intrepid general; and you, Anacharsis Cloots – gentle and melancholy figure through whom German pantheism linked hands with French naturalism! Pride and ambition concealed by hypocritical formulas sacrificed these men, and the Revolution perished with them.3

The Cour du Commerce was also an important site in the years of Revolution, but today it is so densely packed with eateries as to inhibit the imagination. This was not yet the case when I started publishing in the 1980s; the trade counter of Éditions du Seuil was at no. 4. A prominent position was occupied by a tower from the wall of Philippe Auguste, today submerged in an immense patisserie occupying nos. 4, 6 and 8, where Marat established his printing press in 1793 after several more temporary premises. Opposite at no. 9, Dr Guillotin perfected his celebrated machine in the workshop of a carpenter, and is said to have experimented with it on sheep.

Danton lived in a large building at no. 20 on the Cour du Commerce, in the section now displaced by the Boulevard Saint-Germain. This was just where his statue now stands, which is rather exceptional. How is it that Danton has a monument, a street and cafés that bear his name, while Robespierre has nothing in Paris that evokes his memory? After all, it was Danton who established the revolutionary tribunal, Danton who said: ‘They want to terrorize us, let us be terrible!’ But at the start of the Third Republic it was he whom the Radicals chose as an emblematic figure, doubtless more presentable to their eyes than Robespierre.

The Cour de Rohan opens off the Cour du Commerce, a succession of three small courtyards, calm and aristocratic, where Virginia creepers and climbing roses festoon seventeenth-century buildings. In this haven protected by money, often the only people you meet are a few students from the Lycée Fénelon with their sandwiches.

Through the Rue du Jardinet and the Rue Serpente, I enter one of the oldest streets on the Left Bank, the Rue Hautefeuille, where Baudelaire was born and where Courbet had his studio. On the corner of a small cul-de-sac, a bartizan or hanging turret dating from the sixteenth century ornaments the hôtel of the abbots of Fécamp. Its conical trunk is made of a knotwork series in decreasing diameter, each ring bearing a different decoration – a masterpiece of masonry. There are few bartizans left in Paris. On the Left Bank there is another on the same Rue Hautefeuille, on a fine hôtel between the Rue Pierre-Sarrazin and the Rue de l’École-de-Médicine. On the Right Bank, if I am not mistaken, they are all in the Marais: a square one, almost rustic, on the corner of Rue Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie and Rue du Temple; one on the corner of Rue Saint-Paul and Rue des Lions-Saint-Paul (there used to be lions in the great menagerie of the Hôtel Saint-Pol, a royal residence under the Valois); another on the flamboyant Gothic turret of the Hôtel Hérouet, on the corner of Rue Vieille-du-Temple and Rue des Quatre-Fils; one on the turrets that frame the gateway of the Hôtel de Clisson on the Rue des Archives, and that of the Hôtel de Sens on the Rue du Figuier; and finally, at the corner of Rue Pavée and Rue des Francs-Bourgeois, one that decorates the corner of the Hôtel Lamoignon, one of the few Renaissance buildings in Paris. All these are friends of mine, some on habitual routes, others that I make a little detour in order to greet. Each person has their punctuation marks in the city.

The most remarkable thing on the Place Saint-André-des-Arts is not the most apparent. 1 rue Danton could pass as one of the Art Nouveau ‘lite’ buildings that are so common in Paris. Yet this was exceptionally innovative in its time, even serving as a show building for its constructor, François Hennebique. At first sight, you would think it made of stone, but it is built entirely in concrete, including all of its sculptures and cornices. Around 1900, the Hennebique company constructed light and elegant buildings across the world, all in reinforced concrete.

By both day and night, the ensemble formed by Place Saint-André-des-Arts and Place Saint-Michel is lively and noisy, peopled with tourists, students and often also black and Arab youth, which is not so common on the Left Bank, where the Malians are mainly on building sites and the Algerians in delivery vehicles. The Saint-Michel fountain is the meeting point, where the archangel flooring the dragon symbolizes, in Dolf Oehler’s words, ‘the victory of the imperial and bourgeois order over the revolution, the triumph of Good over the bad people of June 1848’.4

The buildings arranged around the Place Saint-Michel are another representation of ‘the imperial and bourgeois order’. With their high mezzanine arcades, their colossal pilasters, their balustrade balconies, they are examples of a monumental and almost neoclassical version of Haussmannism. To the east side you have the Rue de la Huchette and the Rue Saint-Séverin, linked for me and many others with the memory of La Joie de Lire. As this bookshop used to remain open very late, I would go there in the evenings after work. You met friends there, discussed with strangers and joked with the booksellers, pretty girls who liked to guess what book each entering customer would buy. And you sometimes saw, silently passing, the thin and elegant figure of François Maspero, whom I never dared speak to at that time.

It was thanks to Éditions Maspero and La Joie de Lire that I made the acquaintance of Frantz Fanon, Louis Althusser, Paul Nizan, Jean-Pierre Vernant, Fernand Deligny, John Reed, Alexandra Kollontai, Rosa Luxemburg – later than others did, but the surgeon’s trade sadly demands a certain narrowness of focus. Maspero books were magnificent in their typography, their colours, the quality of their paper and printing. I had dozens of them, since lost in successive moves, or lent and not returned, but that is no serious matter – they existed and they nourished me. I buy them again when I find them.

Fined, confiscated, bombed – neither the publishing house nor the Maspero bookshop ever gave in. There is only one other house whose courage and inventiveness could stand comparison: Éditions de Minuit. The others are old maids. Maspero and Jérôme Lindon are heroes from the days of my youth. A street has been named after Gaston Gallimard. Saint Séverin would not complain if one day half of his street was renamed after François Maspero.

To reach the Châtelet from the Place Saint-Michel, the simplest route would be to go straight ahead, but that would force me to walk between the Palais de Justice, the Préfecture de Police and the Tribunal de Commerce – a sorry prospect. A dog’s-leg via the Petit-Pont would involve crossing the queue of tourists in front of Notre-Dame and then walking between the bare wall of the Hôtel-Dieu and the T-shirt stands of the Rue d’Arcole, which is hardly more attractive. In other words, there is no pleasant trajectory to cross the middle of the Île de la Cité.

After the victory of the coming revolution, the sequels of Haussmann’s town-planning assault on this place will have to be cleared. I would happily propose destroying the Hôtel-Dieu and the Préfecture de Police, which would liberate a great space between the two arms of the Seine, from the Palais de Justice (to be transformed into rehearsal and concert halls) to the façade of Notre-Dame. The dismantled stones would be carefully preserved, as building workers from Seine-Saint-Denis would then be entrusted with constructing housing and community facilities on this site. Wouldn’t that be a great idea? Some might fear a shantytown, but I rather think that people would come from across the world to admire this marvel of a new style. It would be the start of a reconquest of Paris.

In the meantime, my choice is to cross the Seine by the Pont-Neuf. To avoid the chaos of the Quai des Grands-Augustins and the kebab joints of the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts, I can zigzag between the two. (On the quai, at least, I have a friendly stopover, L’Écluse, today a restaurant offering a fine selection of Bordeaux wines, but which was in the 1950s a cabaret where I heard for the first time Georges Brassens, and later Barbara.)

The Rue de l’Hirondelle, which starts beneath an arcade on the Place Saint-Michel, is today almost deserted. Francis Carco tells that before the First World War this was the site of La Bolée, a replica of the Lapin Agile in the Latin Quarter, where ‘the clientele, made up of anarchists, prowlers, students, singers, comics, errand girls and poor wretches, feasted cheaply, not at all like a first-class waiting room but rather a third-class one, among dirty wrapping paper, charcuterie and pitchers of cider’.5 There is no longer any trace of the time when the Latin Quarter was dirty and wretched, and the surroundings of the Collège de France the domain of rag-pickers. During the first half of the twentieth century the quarter was gradually disinfected, and the landscape of the 1920s that Léautaud describes in his Journal, Daudet in Paris vécu and Gide in The Counterfeiters was already very different from that of Carco.

With hardly any traffic, and neither shops nor cafés, the Rues Gît-le-Coeur, Séguier and de Savoie are white, calm and silent at any time of day or year. It is not easy to know who lives here, as you do not meet many people. The Rue des Grands-Augustins is more lively (before the Revolution, the Grands-Augustins was an immense monastery on the bank of the Seine, between the Tour de Nesle and the street that today bears its name; the Rue Dauphine was cut through its gardens). At no. 7, a plaque indicates that Picasso painted Guernica here, and that this was where Balzac located the action of The Unknown Masterpiece.

The crossroads where the Rue du Pont-de-Lodi comes out into the Rue Dauphine almost opposite the Rue de Nesle is the domain of the cut-price book dealers. This activity is both discrete and considerable: thousands of volumes leave here for the bargain bookshops that can be found all across France. When I started in publishing, I knew four of the five characters who reigned over this place. By dint of seeing whole swathes of publishers come here over the years, they came to possess a predictive skill, an acute sense of what makes for the success or failure of a book. For the neophyte that I was, this was a precious experience, which often enabled me to jettison doubtful projects. One of their number, René Beaudoin, founded the shop Mona Lisait, where you could find in the basement rare titles that he had republished himself. A great cyclist – he trained the youth team at Gennevilliers – he was run over and killed by a lorry on the Quai de la Mégisserie. The others are still there with their wide range of books behind dark windows that in no way attract the attention of the passer-by.

Looking back from the Pont-Neuf, you see the Monnaie, the Institut de France, the corner of the Louvre colonnade and the Apollo gallery, the clock-tower and nave of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, the top of the Saint-Jacques tower and the façade of Saint-Gervais, the towers of the Palais de Justice, and, on the bridge itself, the two twin buildings that frame the entrance to the Place Dauphine. In this panorama I read a kind of unity that is not simply due to habit: these buildings were all constructed in Paris stone (Louis-Sébastien Mercier: ‘These towers, these belfries, these vaults of temples, so many signs that say to the eye: what you see in the air is missing beneath our feet’6). And the common origin of their material gives this diverse range of monuments a common tint, with subtle variations of Parisian grey. All attest to the great art of successive generations of stonemasons.

This landscape, it is true, is now no more than a vast museum. The dog trainers, lightermen and water-carriers who once animated it have long since disappeared, but after all one has a right to be happy in a museum, as indeed a few steps away regarding the lances of Paolo Uccello or Nicolas Poussin’s Rebecca, so gracious in her blue dress by the fountain.

The ensemble formed by the Pont-Neuf, the Place Dauphine and the Rue Dauphine was the first case of concerted improvement in Paris. (‘Dauphine’ in honour of the little Dauphin, the future Louis XIII, born in 1601.) Henri IV launched two other major projects: the Place Royale (now Place de Vosges), which became so much the centre of elegant life in Paris that people simply said ‘the place’; and the Place de France, which was left on the drawing board after Henri’s assassination. This was to be a semi-circle in the Temple marshes, the intended seat of the royal administration. Its diameter would have been along the city wall (on the Boulevard des Filles-du-Calvaire, near the Cirque d’Hiver), and from its centre would have radiated streets bearing the names of French provinces. The names still remain in this quarter: Poitou, Normandie, Franche-Comté, Beauce… That the plans for the Place Dauphine, the Place Royale and the Place de France were drawn according to the three basic geometrical figures, triangle, square and circle, shows that nothing was left to chance in this project of urban improvement.7

The Place Dauphine has undergone a series of assaults that have done it a good deal of harm. Under the Third Republic, the construction of the massive west façade of the Palais de Justice meant the destruction of the base of the triangle, though for André Breton, when he wrote Nadja in the 1920s, this was still ‘one of the most remote places’, ‘one of the worst wastelands’ of Paris. Then, around 1970, an underground car park was dug beneath the place, ravaging it like the Place Vendôme, Place Saint-Sulpice and many others have been. The ground was raised, and the old cobbles replaced by a sandy covering for scrawny chestnut trees. The result seems to be a public garden that they have not ventured to name as such. Finally, from the 1990s, restaurants mushroomed up along two sides of the triangle, quite taking away its charm. Chez Paul, where I sometimes used to invite my medical students (the young ones at the bottom of the hospital hierarchy), still exists, but now lacks the ambiance of an old Parisian bistrot with its check tablecloths, surly waiters, leeks in vinegar and blanquette de veau.

The narrow Rue du Roule runs past the Samaritaine department store, named after a pavilion on piles that was moored to the Pont-Neuf, with a pump and a chiming clock. Mercier notes that ‘this clock face, seen and questioned by so many passers-by, has gone for months without telling the time. The chimes are as defective as the clock itself; they publicly spout nonsense, but at least people are entitled to make fun of them.’8 The great Samaritaine store, for its part, closed its doors some ten years ago, on the pretext of security – a blatant pretext, but since the owner (Bernard Arnault, LVMH) is a major advertising client, the press showed more than its usual prudence on this occasion.

We are right to be concerned about the future of Frantz Jourdain and Henri Sauvage’s masterwork, even if the project has been entrusted to the Japanese agency SANAA, one of the most highly regarded at the moment, whose buildings in France include the Louvre-Lens. The plans envisage shopping galleries in the basement, ground and first floor, above them office space to finance the project, and on top a luxury hotel – eighty suites with a view of the Seine. We must wish the architects good luck, as the building is highly listed and thus impossible to ‘façade’ – in other words, to gut like a chicken and just keep the shell. The stairs, banisters, the whole precious Art Deco ironwork have to be preserved, and it will not be easy to make the new floors coincide with those of the original building. So as not to ruffle the sensitivity of the Paris municipality, always sharp-eyed as we know, permission to modify the town-planning regulations and build higher has been obtained by including social housing and a crèche. In short, while the choice of architects will probably make it possible to avoid disaster, money and luxury will certainly deprive the good people of one of their traditional haunts for browsing and buying, a store in which ‘you could find anything’, climbed by King Kong in a famous advertisement of the 1970s. The Samaritaine terrace, with its viewpoint indicator and its 360-degree view over the roofs of Paris, will remain accessible to the public, but only in groups of twelve escorted by two fire-fighters.9 It is true that in the meantime LVMH will have offered Parisians the Vuitton foundation in the Bois de Boulogne – a building conceived by Frank Gehry, the architect most prominent in the global media, for Bernard Arnault, the richest man in France.

From the Rue du Roule, I can see the rose window of the transept of Saint-Eustache. In October Nights, Nerval wanders into the Halles with a friend:

This magnificent structure, which blends the flamboyance of the Middle Ages with the more severe symmetries of the Renaissance, is beautifully illuminated by the moonlight, which plays on its Gothic armature, its flying buttresses which protrude like the ribs of some prodigious whale and the Roman arches of its windows and doors, whose ornaments seem to belong to its ogival section.

As the two night-time walkers advance,

The floor of Les Halles was beginning to stir to life. The carts of the various wholesale merchants of dairy products, fish, produce and vegetables were arriving in an uninterrupted stream. The carters who had finished their haul were having drinks in the various nearby all-night cafés and taverns. On the Rue Mauconseil, these establishments stretch all the way to the oyster market; they line the Rue Montmartre from the edge of Saint-Eustache to the Rue du Jour. On the right side of this street you find the eel-mongers; the left side is occupied by the Raspail pharmacies and by licensed cider houses – where you can also get yourself excellent oysters and tripe à la mode de Caen … As we made our way to the left of the fish market, where things only begin to liven up around five or six in the morning when the bidding starts, we noticed a bunch of men sprawled on sacks of green beans, wearing smocks, berets and white jackets with black stripes … Some of them were keeping warm like soldiers huddled around their campfires, others were sitting around their portable stoves in the nearby taverns. Still others were standing near the piles of sacks, discussing the price of beans, using such terms as options, extensions, profit margins, consignments, selling up, selling short – as if they were playing the stock market.10

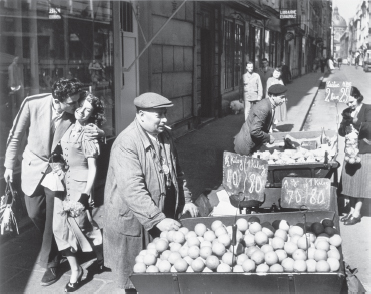

This is clearly Les Halles before Baltard, but what Nerval describes is not too different from the atmosphere I remember from the 1960s, when I came shopping with the Necker hospital cook to prepare for a feast in the staff room. (This was where the interns slept and ate.) The women and men who worked in Les Halles were still like the legends told of them from François Villon to Jean-Pierre Melville. In their clothing, their speech, their very gestures, they had (especially the women) a style, an inventiveness, a humour, a cordiality, that you still find a trace of in certain Paris markets – formerly at the Enfants-Rouges, today at Aligre. Those not old enough to have known Les Halles before their destruction can at least study the photographs that Robert Doisneau took of them over many years: the thousands of crates, the caps, the faces, the overalls, the mist on café windows, the fish and the hams, the flowers and the onions, the lorries, the lights… All that is missing is the smells and the noises. A little further on, the Beaubourg plateau, flat as its name implies and covered with large paving stones, was the lorry park.

In L’Assassinat de Paris, Louis Chevalier recalls the reasons given by those who planned to destroy Les Halles in the late 1950s.11 The main argument was the traffic jams, one of the great complaints of the time – Pompidou’s project was to adapt Paris to the automobile, and the destruction of Les Halles would be the centrepiece of this adaptation.

[Traffic jams] which the interested parties, the lorry-drivers, navigated marvellously, and which they would have been the last to complain about. And the traffic jams throughout the city, and increasingly throughout the conurbation, which the market traffic is held responsible for, although in the early hours of the morning, on an empty and newly washed Boulevard Sébastopol, you can drive very easily, which paradoxically ceases to be the case after Les Halles have closed.

Then there was hygiene:

the legendary dirtiness of Les Halles. Goods left in the open air in every season, exposed to heat, cold, rain, sun, in the dust and mud of the pavements, on the roadway, in the gutter, over drains. It will be understood that I am quoting wholesale the words that I find in this discourse without attempting to put them in order, to arrange them in the way that goods, vegetables for example, are arranged in harmonious constructions that, in the bright light of the lamps, breathe order, beauty, taste and quite obviously cleanliness: so fresh and neat that it would be a shame even to peel them … Curiously, the hygiene argument, brandished by the opponents of Les Halles and the champions of a ‘definitive solution’, was one of the arguments of those shameless people who had the effrontery to defend the destruction of the old port of Marseille: also a miraculous quarter, so like that of Les Halles in many ways, by its fate, by the striking memory that it left right across the world, and above all by the charges made against it, one of these being the danger to public health: enough to make a whale laugh.

To dramatize things yet more, there were the rats, ‘the old medieval fear of rats. “An army of rats”, the word “army” making the danger all the more striking. Despite not having heard the workers at Les Halles talking of their encounters with rats, it made the listeners’ flesh creep, like the fisherman’s famous tale about the octopus.’ And to complete the spectacle, ‘Villon’s fat prostitutes, very far from discreet, some of whom displayed their charms even on the steps of Saint-Eustache’.

Louis Chevalier, who taught the history of Paris at the Collège de France, had been a fellow student of Georges Pompidou at the École Normale Supérieure, and they continued to lunch together from time to time in a small restaurant on the Rue Hautefeuille.

We spoke about everything, our youth, our teachers, our classmates, life, love, poetry, never about philosophy, which neither of us took to, and of course, absolutely never about politics. Also, coming to the point, never about Paris. And yet God knows that on some days the subject imposed itself, burning to be served hot on a plate in the middle of the table. For example, the day after a certain declaration about the Place de la Défense and its towers, published in Le Monde. At the very moment I sat down at the table, it still sat uneasily on my stomach. It seemed to me – perhaps just an illusion – that Pompidou, knowing my ideas on the question were exactly the opposite of his, cast me a smug and inflexible look, which probably meant that with people like me, the people of Paris would still dwell in the huts where Caesar found them.

May ’68 certainly played in favour of the fatal decision. Not that anything much happened at Les Halles during the ‘events’, but the physical and moral clean-up of the capital was in the spirit of the time. Finally, on 27 February 1969, Les Halles were moved out to Rungis.

Should Baltard’s pavilions have been kept? I am unsure. Between the move and their destruction in 1971–2, they were indeed spaces for theatre, dance and music, open for all kinds of events that had no official status, but representing on the contrary a way of defying the authorities and continuing the spirit of May. Had they been given over to commerce and culture, it is likely that they would have experienced the fate of other places preserved after the end of their original activity, sad ‘spaces’ devoted to the sale of T-shirts and souvenirs, to fast food or museums in exile: Covent Garden in London, the Liverpool docks, the Fiat Lingotto in Turin, the port of San Francisco.

But what happened in the 1970s between Saint-Eustache, the Rue Saint-Honoré, the Bourse de Commerce and the Boulevard Sébastopol is truly flabbergasting. In 1974, Giscard became president. This gave him control of Les Halles, along with the prefect of the Seine department, as Paris had not had a mayor since the time of the Revolution and was under the close control of the executive. The Gaullists on the municipal council were sidelined, and the renovation of Les Halles entrusted to a young Catalan architect, Ricardo Bofill. After his project of a great colonnade in Bernini style was rejected, he proposed a more acceptable plan, and his first buildings, more Haussmannian, began to rise from the ground, while the famous hole was dug that was to serve for the Métro station and the future RER.

Everything changed when Chirac became mayor of Paris in 1977. He declared, in a brash rejection of Giscard’s pretentiousness: ‘I shall be the architect in chief of Les Halles, without hang-ups … I want it to smell of chips!’12 Bofill was dismissed (as compensation he was given the renovation of the Vercingétorix quarter), and his buildings, some of which were already three storeys high, were demolished. In the end, the plans adopted were those of Claude Vasconi, and, for the gardens, those of Louis Arretche, known for French-style fine art.

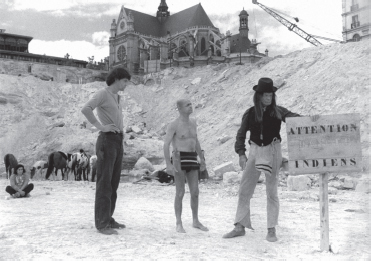

There remained the question of the hole. The digging had to be very deep in order to put the RER station at the same level as the Paris Métro, and the excavation was enormous – to get an idea of this, it is worth seeing Touche pas la femme blanche, an excellent parody Western shot inside the hole by Marco Ferreri, with Marcello Mastroianni and Catherine Deneuve. The station only occupied the bottom of the excavation. What should be done with the rest? After dismissing a number of far-fetched projects (such as a ‘delphinarium’ for dolphins and other cetaceans), the joint public-private company in charge of the operation (SEMAH), concerned for its profitability, decided to give the biggest slice of the cake to the commercial centre that we know today under the name of the Forum. Since that time, the people who decide on the future of Les Halles are the powerful association representing the businesses established there and the developer Espace Expansion, a branch of Unibail. The hundreds of thousands of Parisians and banlieusards who pass through every morning remain underground, well protected from air and light.13

© Film 66/Mara films/Laser production

Touche pas la femme blanche, film by Marco Ferreri. Collection Christophel.

At the time that I visited Les Halles to take notes, the construction of the new ‘canopy’ was still unfinished. As Wittgenstein advises, ‘whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must remain silent’.

The square defined by Rue des Innocents, Rue Saint-Denis and Rue Berger (the fourth side has neither form nor name) more or less corresponds to the space occupied until the end of the eighteenth century by the Innocents cemetery. Jean Goujon’s decorated fountain was not in the middle, as this was where the great pit was located that had received dozens of corpses every day since Philippe le Bel. It abutted the Innocents church, on the corner of Rue Saint-Denis and Rue aux Fers (now Berger), and so had only three sides. The cemetery was decorated with danses macabres such as were frequently painted in the fifteenth century, and we are told by Sauval – a historian of Paris who wrote in the 1650s – of a most marvellous skeleton by Germain Pilon. Jean Goujon, Germain Pilon: if French painting lagged somewhat behind in the fifteenth century, sculpture was at a peak. Those who prefer to see statues in their place of origin may admire in the church of Saint-Paul Germain Pilon’s Vierge de douleur, and by Jean Goujon, besides the adorable nymphs on the Fontaine des Innocents, Les Quatre Saisons in the court of the Carnavelet museum.

The Innocents was no ordinary cemetery. Beneath the arches along its walls (the mass graves where bones were piled up to relieve the overcrowded pits), all kinds of ambulant pedlars, from linen maids to fortune-tellers, made it a centre of Parisian life. It was also one of the only three places illuminated in the deep night of medieval Paris, the two others being the Porte du Grand-Châtelet and the Tour de Nesle, where a lantern signalled to mariners navigating the Seine that they were reaching the city.

Towards the end of the Ancien Régime, however, a new concern for hygiene arose. ‘The knowledge recently acquired on the nature of air cast a very clear light on the danger of this pollution’, wrote Mercier. The result was that in 1780 the cemetery was closed, and the bones transferred to the quarries south of Paris that were henceforth known as the Catacombes. What a removal! ‘Just imagine the flaming torches, this immense pit open for the first time, the fires fuelled with coffin planks, this frightening enclosure suddenly lit up in the silence of night!’14 The church and the mass graves were then demolished, and the ground paved to serve as a marketplace. The fountain was dismantled and rebuilt stone by stone in the centre, but a fourth side was now needed. The task was entrusted to Pajou, a neoclassical sculptor, who acquitted himself honourably – this is today the south-facing side.

The narrow portion of the Rue Saint-Denis that leads to Châtelet crosses or adjoins streets heavy with history. To the right, along the arcades of the Rue de la Ferronnerie, Henri IV was killed with a dagger by Ravaillac while on his way to inaugurate the chapel of the Saint-Louis hospital. To the left, the Rue de La Reynie bears the name of the first lieutenant-general of police, appointed by Colbert in 1667, who set out to suppress seditious writings, close the Courts of Miracles, and expel what remained of the poor and deviant after the ‘grande refermement’ of 1657, when the homeless population – beggars, mad, vagabonds, prostitutes – were collected and locked up in the Salpêtrière or Bicêtre. La Reynie was also responsible for the first public lighting, glass cages containing candles that were hung on ropes outside the first floor of buildings. Further on, the Rue des Lombards evokes the memory of the Italian moneychangers and money-lenders established there from the time of Philippe Auguste.

Along the way, I ponder the fact that I am recounting this walk as if it were done at one go, as if I had completed the trajectory in a single day, without stopping for a coffee or to shelter from the rain, without ever breaking it off to resume the next day. And so there is a share of fiction and even improbability in the account. For justification, I can cite an illustrious precedent, that of Proust’s Time Regained. Alone in the library of the Prince de Guermantes, the narrator explains that after so many years wasted in idleness and indecision, he is going to get to work and finally write a book … the book that we have just read in three thousand pages. Nor is this the only affront to verisimilitude in this final volume of Proust’s magnum opus. Combray, which had previously been situated in the Beauce, in 1916 suddenly becomes a village on the front line of the war, somewhere in Champagne. ‘The battle of Méséglise’, Gilberte writes to the narrator, ‘lasted for more than eight months; the Germans lost in it more than six hundred thousand men, they destroyed Méséglise, but they did not capture it.’15 This is not just one of those inconsequential trivialities scattered throughout the work, where a secondary character mentioned early on becomes a thousand pages later the cousin of someone else instead of being their nephew. Combray is a central place in the book, and its shift in location can only have been intentional. Similarly, after a long nighttime walk with Charlus, ‘descending the boulevards’, the narrator leaves him, continues alone and happens to enter, to quench his thirst, what he believes to be a hotel but is in fact a brothel kept by Jupien, where Charlus has himself chained to the bedstead and whipped – a long passage, closely worked and deliberately improbable. Thus, the end of Time Regained becomes a night-time fairyland (‘the ancient East of the Thousand and One Nights that I used to love so much’), lit by searchlights seeking the skies for German planes.