CHAPTER 4

Return to earth: Place du Châtelet, the geographic centre of present-day Paris. One might almost believe it has always been here, at the intersection of the north-south and east-west axes, yet it is purely a creation of Haussmann. At the time when Nerval, Balzac, Eugène Sue and the young Victor Hugo were writing, the quarter between the Hôtel de Ville and the Louvre colonnade was a tangle of medieval alleys, the densest in the whole city. At the start of A Second Home, Balzac describes the Rue du Tourniquet-Saint-Jean, ‘formerly one of the most tortuous and gloomy streets in the old quarter that surrounds the Hôtel de Ville’. Even at its widest part it was no more than six feet across, and ‘in rainy weather the gutter water was soon deep at the foot of the old houses, sweeping down with it the dust and refuse deposited at the corner-stones by the residents’.

As the dustcarts could not pass through, the inhabitants trusted to storms to wash their always miry alley; for how could it be clean? When the summer sun shed its perpendicular rays on Paris like a sheet of gold, but as piercing as the point of a sword, it lighted up the blackness of this street for a few minutes without drying the permanent damp that rose from the ground-floor to the first storey of these dark and silent tenements. The residents, who lighted their lamps at five o’clock in the month of June, in winter never put them out. To this day the enterprising wayfarer who should approach the Marais along the quays, past the end of the Rue du Chaume, the Rues de l’Homme Armé, des Billettes and des Deux-Portes, all leading to the Rue du Tourniquet, might think he had passed through cellars all the way.

All that remains of this are a few street names, Rue de la Tâcherie, Rue de la Coutellerie, Rue de la Verrerie. The Rue de la Vieille-Laterne, which Nerval chose to die in, ran from the Rue de la Vieille-Place-aux-Veaux to the Place du Châtelet of the time, and it is said that the spot where he hanged himself corresponds to the centre of the curtain of the Théâtre de la Ville. At that time, the Place du Châtelet was quite small, centred on the Victoire column built under the Empire. This was further east than the centre of the square designed by Haussmann, so that when he reconfigured the quarter, the column had to be shifted some ten metres further west.

Of the four sides of today’s Châtelet, there are three that fulfil their role very well. To the south, the Seine and the view of the towers of the Palais de Justice; to the east and west, the two theatres built by Davioud, almost symmetrical but not quite, with an eclecticism that is correct without being boring. It is the fourth side that doesn’t work, making the Place du Châtelet a great traffic intersection rather than a place for strolling and meeting people. The Haussmann cuttings – Rue des Halles, Boulevard Sébastopol and the unfortunate Avenue Victoria – open gaps that the thin façade of the Chambre des Notaires fails to fill. As for the central reservation, walled off by an almost continuous metal balustrade, this is neglected indeed: a newspaper kiosk, a Métro entrance, a taxi rank, a cylindrical advertising column, some lines of sickly trees. Only the coping of the fountain around the column offers tourists anything to sit on, and in hot weather the sphinxes that spout water bring some freshness amid the heavy traffic.

© Charles Marville/Musée Carnavelet/Roger Viollet

The moving of Châtelet column.

The axis of the Boulevards Sébastopol and Strasbourg is a paradigm of Haussmann’s cuttings, and a successful one, integrated both into language (‘le Sébasto’) and into the quarters that it runs through and connects. The extremities of the perspective are marked by the dome of the Tribunal de Commerce to the south and the glass panels of the Gare de l’Est to the north – François Loyer noted that this dome, oddly off-centre on a flat roof, has no function other than a visual one.1 The great merit of this Haussmann cutting is that it did not destroy the quarters it opened up, except for the short section between Châtelet and the Rue de Rivoli, devastated as we have just seen. True, the boulevard did involve destruction, but this was limited in width. Neither the Rue Saint-Martin, nor the Rue Saint-Denis, nor the many small side streets, suffered significant damage; they keep the same lines and almost the same buildings as at the time of Balzac and the young Baudelaire.

Not all of Haussmann’s grand projects show the same design. Some were tantamount to murder in the name of town-planning: wholesale clearing, massive and systematic destruction, displacement of population. These ravages particularly affected two zones towards which the Second Empire felt a mixture of fear and contempt: the Île de la Cité and the Hôtel de Ville quarter on the one hand, and then the region around the Place du Château-d’Eau, which would become the Place de la République.

In his Mémoires, Haussmann expresses his disgust for the vile crowd he was forced to pass through in walking from the Chausée-d’Antin where he lived to the law faculty where he was a student. The brigands, prostitutes and immigrant workers crowded into the sordid streets around the Hôtel de Ville and Notre-Dame had to be got rid of, being the source of both cholera and unpredictable riots. (These immigrant workers, who hailed from the Creuse – where there is still a village called Peintaparis – Corrèze or Brittany were viewed as Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Algerians and Malians would be later on.)

The second region marked for destruction, around the Château-d’Eau, was, along with the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the most turbulent in the city, the quickest to erect barricades and fight to the death. In June 1848 – still a recent memory in Haussmann’s time – it had taken tens of thousands of soldiers, supported by artillery, to supress the insurrection in the Faubourg du Temple. There was therefore no remedy short of wholesale clearance: an enormous hole was cut in the urban fabric, erasing the end of the Boulevard du Temple (the ‘Boulevard du Crime’ with all its theatres) and the start of the Boulevard Saint-Martin. This hole was transformed one way or another into a square whose essential element was the barracks – which still exists. From here, by new roadways (Rue Turbigo, Boulevard Magenta, the Canal Saint-Martin newly covered to make the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir), the cavalry and artillery could set out to every corner of the city. The difficulties subsequently experienced in improving the Place de la République were bound up with this past, as there is a difference in kind between an empty space to be bordered and a space expressly designed as a square.

But it was impossible to remove all the dangerous classes from Paris. Workers were need for the gigantic constructions that would turn the city upside down. Hence the second kind of Haussmann cuttings, which genuinely have more to do with town-planning than with class struggle, fitting into the urban fabric without devastating the quarters affected. Thus, on either side of the Rue Turbigo, the old revolutionary section of the Gravilliers on one side and the pretty Rues Meslay, du Vert-Bois and Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth on the other remain almost unchanged – as likewise, either side of the Rue de Rennes, do the ancient Rues du Vieux-Colombier, du Four, du Sabot and the little Rue Bernard-Palissy which has long been the home of Éditions de Minuit. People have forgotten that these streets were formerly working class. It was only in the course of the twentieth century that they passed into the hands of the well-to-do bourgeoisie, when living in old buildings became a modern fashion. Until the First World War and perhaps even into the 1930s, those with sufficient means lived in the good districts. Proust lived on Boulevard Malesherbes, Rue de Courcelles, Boulevard Haussmann, Rue Hamelin, and his characters dwell in the hôtels of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, or more often in the newer and elegant quarters of the 8th and 17th arrondissements. Only an eccentric like Swann would prefer the Quai d’Orléans on the Île Saint-Louis.

From Châtelet, a few steps are sufficient to reach what remains of the great church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie, the Tour Saint-Jacques. By day, this is a Gothic vestige that was perhaps more beautiful when wrapped in scaffolding (‘the prodigious scaffolding of monuments under repair, applying to the solid body of the architecture their modern architecture of such paradoxical beauty’, as Baudelaire wrote2). But by night it is a different story. The tower is transfigured, standing out against the black background like a fantastic apparition. André Breton mentions it several times, for example in his poem ‘Vigilance’:

The tottering Saint Jacques tower in Paris

In the semblance of a sunflower

Strikes the Seine sometimes with its forehead and its

shadow glides

Imperceptibly among the riverboats…

A poem he revisits in Mad Love: ‘You may well have known that I loved this tower, I still see at this moment a whole violent existence organized around it to understand us, to contain the distraught in its cloudy gallop around us.’ And the final chapter of Arcanum 17 is completely devoted to it:

It is certainly true that my mind has often prowled around that tower, for me very powerfully charged with occult significance, either because it shares in the doubly veiled life (once because it disappeared, leaving behind it this giant trophy, and again because it embodied as nothing else has, the sagacity of the hermeticists) of the Church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie, or because it is endowed with legends about Flamel returning to Paris after his death.3

At the time when the immense church of Saint-Jacques was erected at the heart of the butchery quarter, the roadway on its eastern side was not yet called Rue Saint-Martin, but Rue Planche-Mibray towards the Seine, then Rue des Arcis as far as the Rue de la Verrerie. In June 1848, the barricade on the Rue Planche-Mibray was under the command of a sixty-year-old shoemaker named Voisambert.4

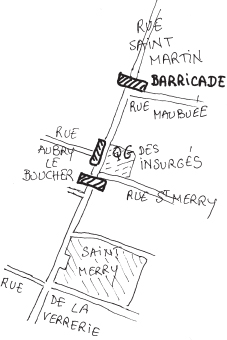

After the Rue de Rivoli, the Rue Saint-Martin leads to another battlefield, where the epilogue to the insurrection of 5–6 June 1832 took place. This uprising, which began with an immense crowd gathered behind the coffin of the republican general Lamarque, had been suppressed in the night of 5 June and the morning of the 6th. The last group of insurgents had retrenched to the Saint-Merri cloister, which became a real fortress. To understand what took place there, one should read the letter that Charles Jeanne, the head of the insurgents, wrote to his sister.5 The centre of their stronghold was a house at no. 30 on the Rue Saint-Martin, with a system of three barricades around it, ‘the first at the corner of the Rue Saint-Merri continued outward and cut the Rue Saint-Martin at a right angle; the second, also at a right angle to the former, blocked the Rue Aubry-le-Boucher; and finally the third, raised at the corner of the Rue Maubuée, brought this latter street within our retrenchments’. On several occasions, the National Guard were repelled, leaving dozens of dead on the roadway (‘Then they were no longer a disciplined body, but a cloud of Cossacks in complete rout’), and it was only the artillery, firing simultaneously through the Rue Aubry-le-Boucher and along the Rue Saint-Martin from Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs, that reduced this stronghold. Jeanne and a dozen of his followers managed to beat a path by means of bayonets across the troop of assailants. It was on this 6 June that cannon were used for the first time against the people of Paris – the Lyon silk weavers had already had experience of this the previous year.

This insurrection aroused both interest and fascination on the part of several contemporary writers, whereas the events of June 1848, though far more threatening to the established system, as well as far more deadly, had no literary echo at the time – the silence of repression.6 The underlying reason for this difference seems clear. While the men of June 1848 were, as we saw, anonymous proletarians who interested no one, the combatants of June 1832 included a number of students, sons of the bourgeoisie, as Stendhal ironically refers to in the opening lines of Lucien Leuwen: ‘He had been expelled from the Polytechnique for having gone for an inappropriate walk, on a day that he and all his fellow students were detained; that was the time of one of the famous days of June, April or February 1832 or 1834.’ Lucien was the favoured son of a big Parisian banker, who ‘gave dinners of the highest distinction, almost perfect, and yet was neither moral, boring, nor ambitious, but simply fanciful; he had a large number of friends’. (A question that arises here is why Stendhal chose ‘Leuwen’, an Alsatian variant of ‘Lévy’, for a family whom nothing in the book signals to be Jewish. Were ‘Jew’ and ‘banker’ so connected in people’s minds at this time?)

Among those who wrote about the insurrection of 1832, Victor Hugo in Les Misérables comes first to mind, with the barricade on the Rue de la Chanverie where Gavroche dies, but this book was written thirty years after the events. At the time, the young Hugo was still the reactionary he would remain until June 1848, the date (and cause) of a political turn that would go so far as to lead him to support the defeated and persecuted Communards of 1871. In Things Seen, under the date 6–7 June 1832, we read:

Riot around Lamarque’s cortege. Madness drowned in blood. One day we shall have a republic, and when this comes of itself it will be fine. But let us not pluck in May the fruit that will not be ready until July; let us know how to wait. The republic proclaimed by France in Europe will be the crown of our white hairs. But we should not let boors stain our flag red.

The juste milieu, to say the least, and a contrast with what Heine wrote in one of his reports for the Augsburger All-gemeine newspaper: ‘It was the best blood of France which ran in the Rue Saint-Martin, and I do not believe that there was better fighting at Thermopylae than at the mouth of the Alley of Saint-Méry and Aubrey-des-Bouchers [sic].’7

The pre-eminent writer of this time, Chateaubriand, wrote in Book 35 of his Mémoires:

General Lamarque’s cortege led to two blood-stained days and the victory of Quasi-Legitimacy over the Republican Party. The latter, fragmented and disunited, carried out a heroic resistance. Paris was placed in a state of siege: it was censure on the largest possible scale, censure in the style of the Convention, with this difference that a military commission replaced the revolutionary tribunal. In June 1832 they shot the men who brought them victory in July 1830; they sacrificed that same École Polytechnique, that same artillery of the National Guard, who had conquered the powers that be, on behalf of those who now struck at them, disavowed them and cast them off!

Admirable! Contempt for Louis-Philippe led Chateaubriand to accept the memory of the Convention – some actually said that the June insurgents included supporters of Charles X and the Duchesse de Berry.

In Lost Illusions, Michel Chrestien, the only honest and courageous republican in the whole of Balzac’s Comédie humaine, is killed on the barricade of the Rue Saint-Merri: ‘this gay bohemian of intellectual life, the great statesman who might have changed the face of the world, fell as a private soldier in the cloister of Saint-Merri’. He was buried in Père-Lachaise by his friends of the Cénacle who had taken the risk of coming to find his body on the battlefield.

There is no book by George Sand contemporary with these events (though she alludes to them in novels of the 1840s and in The Story of My Life). But in a letter to her friend Laure Decerfz, on 13 June 1832, she wrote:

To discover by the Seine below the Morgue [she lived on the Quai Saint-Michel] a red furrow, to see the straw that scarcely covers a heavy cart being spread, and to perceive under this crude wrapping twenty, thirty corpses, some in black and others in velvet jackets, all torn, mutilated, blackened by powder, sullied by mud and dried blood. To hear the cries of women who recognize their husbands and children here, all that is horrible.

There are other texts on the insurrection of 5–6 June 1832 besides those of the famous writers of the time. In September of the same year there appeared a novel entitled Le Cloître Saint-Méry, a love story set during the insurrection, and the work of a young author, Marius Rey-Dussueil, who worked for the republican paper La Tribune. The author was charged with provoking civil war and contempt for the royal government. He was acquitted in February 1833 but the book was destroyed by court order.

Agéno Altaroche, who was only twenty and not yet the poet and singer he would become, wrote a poem entitled ‘6 June! Mourning’, which begins:

Dead! Dead! They are no longer here, our brothers!

Decease has closed their bloody eyelids

They died side by side, all struck in the heart!

See, see the great funerals pass …

Here the echo on the fields of battle

The ferocious cry of the conqueror!

Another young man, Hégésippe Moreau, who died of consumption a few years later, wrote a long poem entitled ‘5 and 6 June 1832’, with the repeated refrain:

They are all dead, the death of heroes,

And despair is without weapons;

At least against the executioners

Let us have the courage of tears.

Let us imagine for a moment that the ‘coming insurrection’ goes badly: who will be found to honour those who are shot? A bad question that we should dismiss.

The part of the Rue Saint-Merri that served as a battlefield in 1832 now exists only in memory. It is possible all the same to observe here a rather infrequent phenomenon, two buildings abutting and even interpenetrating, one of which is an honest construction from the 1920s and another that might be called contemporary despite already being fifty years old. These are the municipal baths of the 4th arrondissement and Renzo Piano’s IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique), his first commission after the Beaubourg. I do not know whether the preservation of the baths was an architectural necessity or a deliberate choice. At all events, the way in which the IRCAM encompasses and respects these, the care taken to align the cornices of the one with the ironwork of the other, the intelligent decision to place the more modern façade towards the Stravinsky fountain designed by Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle rather than facing the Beaubourg, the choice of material – all this attests to an understanding modesty. As for the material, the small terracotta blocks that Piano used for the IRCAM (I am not sure whether we can call them ‘bricks’) are almost the same colour and exactly the same thickness as the bricks of the baths:

We took particular care to place the tower in its context. The reminder of the Beaubourg is apparent at the top, the bare steel structure at the top of the lift cage and the network of aluminium supports for the glasswork and cladding. The opaque portion facing the corner of the square is of the same brick-red colour as the adjacent building [the bathhouse]. In any case, there is no question here of a visible wall, but of panels in terracotta. The terracotta element affixed to concealed bars is spaced by aluminium elements that form the only visible part of the fixture. The elements of the façade naturally resemble the neighbouring bricks in terms of their texture and colour. To accentuate the effect, we had them worked, horizontally incised, to give the same perception in terms of their dimensions. A small example of artisanal attention to decoration, which contributes to strengthening the link of the building to its environment.8

Piano went on to use this material on many subsequent occasions, particularly in Paris for the housing ensemble on the Rue de Meaux.

Was it legitimate to name this centre, the Piano and Rogers building, after Pompidou, rather than the expressway on the Right Bank? I would say both yes and no. Yes, as Pompidou championed the creation of a great centre of contemporary art on the site made available by the destruction of Les Halles. He organized a genuine competition – very different from the masquerade mounted by Delanoë in 2002 for the renovation of the site – and accepted the jury’s decision. And no, as the Piano and Rogers project was in no way to his liking. His artistic tastes were those of a provincial bourgeois who read Le Figaro Magazine (his office was decorated by Agam), and the ‘hippy’ character of the two winning contestants, who arrived at the ceremony tie-less, in shorts (Piano) and yellow shirt (Rogers), was equally uncongenial.9 It was Jean Prouvé, the president of the jury, who was responsible for the triumph of these two quite unknown architects more than thirty years ago. There was at least a tacit connivance between them: Piano and Rogers knew and admired Prouvé’s work, and as the pioneer of metal architecture he could not fail to be seduced by their audacious ‘Meccano’ construction, and the great difference this represented from the Beaux-Arts style that was flourishing at the time (and indeed still flourishes today).

The opposition to going ahead with the prize-winning project did not come from Pompidou, but from the prefect. Piano and Rogers had had the idea, as important for them as the architecture itself, of not using the entire space available: ‘We wanted to create a plaza, a kind of clearing, whose life would be complementary to the activities proposed at the Centre … Without bystanders, fire-eaters and street traders the plaza would not be what it is. It is thanks to the plaza that the Centre genuinely belongs to the city.’ Built in a conch shape like the plaza outside the Palazzo Publico in Siena, the slope of the plaza leads gently towards the doors of the Centre. This required the segment corresponding to the Rue Saint-Martin to be pedestrianized, but:

In the early 1970s the car was master of Paris. There were no pedestrian streets, and the public authorities allowed traffic and parking almost everywhere. The Paris prefecture was particularly hostile to a project that would extend a pedestrianized Rue Saint-Martin towards the Centre. The Rue Saint-Martin, continued by the Rue Saint-Jacques, formed the north-south axis of the capital, which there could be no question of interrupting by banning traffic. ‘The Rue Saint-Martin is the longest street in Paris’, the prefect kept saying. ‘You cannot cut off the longest street in Paris, it’s impossible!’

The great building, inaugurated in 1977, was for a long while a place for the people. There was no control on entry, in the hall you met all kinds of characters, sometimes with a can of beer in their hand, and guys from the banlieue could take the escalator to admire the view over Paris from the fifth floor. This was in line with what the creators intended: ‘In the end, it’s not that important for the Centre Pompidou to contain a museum or a library. The main thing is for people to meet here, in a certain everyday way, without having to pass through a gate and being checked like in a factory. It was to promote contact, to mix genres, to mingle different activities, that we imagined a giant Meccano construction overlooking the city.’ When the Centre was renovated in 2010–12, all this was brought to order: the Vigipirate security system helped sort out entrants, the hall was redesigned to discourage loafers, the escalator is now accessible only with a ticket for the exhibitions, and the dishes on offer in the fifth-floor restaurant cost around 30 euros. We’re now with the right class of people.

Perhaps this is not the worst retreat from the Centre’s original design and its functioning in its early years. Like many other people, I can remember the exhibitions in the late 1970s mounted by a Swedish neo-Dadaist named Pontus Hulten. You came out of the Paris–New York, Paris–Berlin and Paris–Moscow exhibitions quite intoxicated, your only regret not still being inside. Since that time the level of exhibitions at the Centre has followed a steadily declining curve, ending up at the time I am writing with a celebration of the work of Jeff Koons, the most costly artist in the world thanks to his inflatable rabbits and little sugar pigs, or a Le Corbusier exhibition whose theme is ‘the measure of man’, carefully avoiding any debate on either the master’s political friendships or his more debatable projects, such as the Voisin plan that envisaged the destruction of Paris.10 Have we touched bottom? Let’s wait and see.