CHAPTER 6

Leaving the monumental gates for the region of the railway stations, you enter the faubourgs. As applied to Paris, this is an odd word, since if fau comes from the Latin fors, the characteristic of a faubourg is to be outside the city, whereas the Paris streets that bear this name are, if not central, at least well within the urban perimeter. This is of course a question of history. In the early eighteenth century, after crossing the tree-planted boulevard that marked the limit of Paris, you were in the country, where the major Paris streets continued along paths of beaten earth bordered by market gardens, vines and windmills. But Paris was very close, so much so that in the course of that century these earthen paths were paved and served as markers for an urbanization that advanced steadily from the centre despite royal decrees. It was these routes that would form the faubourgs, outside the official limits of the city until the end of Louis XVI’s reign – hence their name – then included in Paris when the Wall of the Farmers-General shifted the boundary. Previously Paris had come to an end at the Bastille, the Porte Saint-Martin and the Tuileries, but it now extended via the Faubourg Saint-Antoine to the Barrière du Trône (now Place de la Nation), via the Faubourg Saint-Martin to the Barrière de La Villette (now Stalingrad), and via the Champs-Élysées to Étoile. The next leap, the annexation of the ‘crown villages’ in 1860 (Vaugirard, Passy, Les Batignolles, Montmartre, Belleville, etc.), ended up making the old faubourgs almost central. Yet in literature the ambiguity remained: the faubourgs are very present in Baudelaire (‘Le faubourg secoué par les lourds tombereaux’ in ‘The Seven Old Men’, ‘Au coeur d’un vieux faubourg, labyrinth fangeux’ in ‘The Rag-Pickers’ Wine’, examples abound1), without our ever knowing their precise location. Much later, when Eugène Dabit wrote Faubourgs de Paris in 1933, he included the Rue de Ménilmontant, the Rue de Choisy-le-Roi and even the Rue de Montlhéry.

From the Porte Saint-Denis and the Porte Saint-Martin, the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis, the Boulevard de Strasbourg and the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin run almost parallel – ‘almost’, as the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis bends a little towards the Gare du Nord, while the other two make a straight line towards the Gare de l’Est. Despite the short distance between them, each of these streets has its specific identity, population and beauty.

The Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin is open, airy, almost peaceful despite the traffic. As Thomas Clerc wrote in his book on the 10th arrondissement, ‘all the buildings in this fine street, which escaped Haussmann, are different from one another – it is a faubourg, with its irregular curve and its rebel spirit’.2 This book is almost ten years old and the street has changed: fewer ready-to-wear wholesalers, more boarded-up shops, more couscous and Chinese restaurants, and an increasing number of African hairdressers as you continue. On the right-hand pavement, Le Splendid, whose hour of glory goes back to the 1970s, now leads a discreet existence. Further along, the Passage du Marché opens onto a Haussmannian building that welcomes you with its sculpted décor, and leads to a pleasant coin (a coin being less than a quartier but more than a crossroads), a small open space bordered by the Saint-Martin market, an ugly building from the 1960s, a fire station and, on the corner with the Rue du Château-d’Eau, a good-quality brasserie, Le Réveil du 10e.

Between the barracks and the mairie of the 10th arrondissement, the little street called after Pierre Bullet is as chaste as that of his colleague Blondel, on the other side of the Porte Saint-Martin, is light, devoted as it is to tariffed love. The Rue Pierre-Bullet runs into the Rue Hittorff, tiny and ending in a kind of cul-de-sac. The Paris municipal counsellors did not do Hittorff proud, perhaps because he was ‘Prussian’. The architect who renovated the Place de la Concorde, with the idea of centring it on the obelisk, who built the Cirque d’Hiver, the Théâtre du Rond-Pont des Champs-Élysées, the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul on the Rue La Fayette, the mairie of the 5th arrondissement as a pendant to Soufflot’s Faculté de Droit, and such a masterpiece as the façade of the Gare du Nord, deserves better than this wretched little street.

The mairie of the 10th arrondissement, built in the 1890s, is a good culmination of nineteenth-century eclecticism. The objective is clear: a large building in French neo-Renaissance style, neo-Chambord if you like, more coherent and in my view more successful than the majority of Parisian mairies, which are indecisive and often lazy in style. Opposite it is the start of the Passage du Désir, with its almost monastic silence, low and regular buildings alternately in brick and white stone, which despite its name is a kind of Parisian convent. But its closed windows and its many boarded-up shop fronts lead us rather to fear the intentions of some developer or a semi-public company.

After its intersection with the Boulevard Magenta, the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin widens, flaring to envelop the apse of the Saint-Laurent church on the left and the former convent of the Récollets, now the Maison de l’Architecture, on the right. From the large triangular square to the east side of the Gare de l’Est, it heads towards the rotunda of La Villette.

The Boulevard de Strasbourg is far from being merely a corridor for motor vehicles. We have to admit that it begins badly: of its four corners with the Boulevard Saint-Denis, two are occupied by banks, the third by a KFC (whose founder, as depicted on the logo, looks rather like Trotsky), and the fourth, presently a construction site, leads us to fear the worst. But very soon you encounter the pretty Théâtre Antoine, below whose triangular pediment are mosaics in lively colours that illustrate Comedy, Music and Drama. Opposite, on the corner with the Rue de Metz, is one of the finest Art Deco buildings in Paris, ornamented with golden peacock wings that sparkle in the sunshine.

The boulevard then bisects a roadway that that was built as a unity: on the right the Rue Gustave-Goublier and on the left the Passage de l’Industrie, entirely devoted to hair products, from wigs and hairpieces to perfumery. It ends with a Palladian window (three bays, with the centre one higher than the other two and topped by a semi-circular arch) before coming out on the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis. A few metres further, also on both sides of the boulevard, is the famous Passage Brady. The left-hand section houses Pakistani and Indian restaurants beneath a glass roof with two continuous rows of panels. To the right is the famous costumier Sommier, who since 1922 has hired out every kind of uniform or disguise. You can emerge equally as a traditional policeman in a cape, a tango dancer or a Napoleonic general. When I was an intern in the 1960s, we would go there before parties. (Is there still this custom? To be sure, its disappearance would be no great loss, being as it was a mixture of machismo, crude humour and caste spirit.)

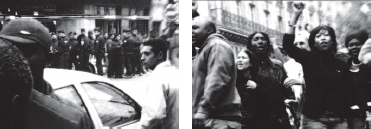

From the Passage Brady to the Rue du Château-d’Eau and beyond is the exclusive and unchallenged domain of African coiffure, a little bit of Africa in Paris, where touts practise their eloquence leaning against the Métro railings, where hairstylists work in shops of all colours, under names you might find in Cotonou or Lagos: ‘Saint-Esprit Cosmétique’ or ‘God’s Rock’. The whole African continent is represented, English-speakers as well as French – even Jamaicans. The ambience is noisy and friendly, even if there are times when you can no longer laugh: a fine short film by Sylvain George, N’entre pas sans violence dans la nuit, captures a moment of revolt when the whole quarter confronted the police and even repelled them for a while, showing that African inventiveness can find applications in many fields.

N’entre pas sans violence dans la nuit, film by Sylvain George.

Like the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin, the Boulevard de Strasbourg widens into a large square in front of the Gare de l’Est, from which you can see several kilometres away the dome of the Tribunal de Commerce. This is the terminus for buses whose numbers start with ‘3’: the 30 that runs to the Trocadéro, the 31 to the Étoile, the 32 to the Porte d’Auteuil, the 35 to the Mairie d’Aubervilliers, the 38 to the Porte d’Orléans. George Perec, in Species of Spaces, explains how to know where Paris bus lines start from their numbers (those beginning with ‘2’ from the Gare Saint-Lazare, with ‘4’ from the Gare du Nord, etc.). He even claims that the second digit also has a meaning, but here I think he exaggerates a little.

The Gare de l’Est, with its long colonnade, its glass canopy overlooked by statues of Verdun (on the right, with helmet) and Strasbourg (on the left), its low buildings, its pedestrianized paved court, is the most welcoming of the major Paris stations. It was almost provincially calm even, until the TGV de l’Est came into service. True, you can not complain that it no longer takes five hours to reach Strasbourg, but the station’s east wing now houses a commercial centre in which ‘brands’ offer their usual displays. Let us remain in the hall of the ‘Strasbourg departure’, where a gigantic painting recalls less peaceful moments.

For those wishing to reach the Gare du Nord from here, the best route is the Rue d’Alsace. Above the twin flights of steps that make a fine oval, the street becomes a balcony over the railway. There has been here for a long time a bookshop very properly called La Balustrade, which was still orthodox communist until a few years ago. Since the death of its owner – whom I used regularly to see selling L’Humanité Dimanche when I lived on the Rue de Sofia – the window instead displays scientific books. On the corner of the Rue des Deux-Gares that leads towards the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis, a café bears another well-found name: Au Train de Vie. Here you are already very close to the concrete lattices bordering the bridge on the Rue Gayette, from which Gilles Quéant jumped into thin air at the end of Jean Rouch’s Gare du Nord.3

But let us return to the Porte Saint-Denis. On the corner between the Faubourg and the Boulevard Saint-Denis is a building from the 1880s. Beneath the second-storey balcony is the sculpture of a standing hooded figure, with the inscription ‘Au grand Saint-Antoine’. He holds a book under his right arm, and his left hand is caressing a pig, which suggests that there used to be a charcuterie in the premises now occupied by an optician’s. (There are several representations of St Anthony accompanied by a tame pig – or boar?) What is certain is that the good old Paris charcuteries, with their mountains of celeriac remoulade, their breaded pig feet, their lobster halves and vol-au-vents, are in the process of disappearing, often replaced by their Chinese counterparts.

Stairway, Rue d’Alsace.

A few metres further is the entrance to the Passage du Prado, an L-shaped arcade whose other branch exits onto the Boulevard Saint-Denis. Some twenty years ago this was the domain of the sewing machine: new and second-hand, repairs, spare parts for all makes, threads, bobbins. No trace of this remains, perhaps because the more or less clandestine sewing workshops of eastern Paris that employed Chinese or Turkish workers have also gone. From two apartments in which I have lived, on the Rue du Faubourg-du-Temple and now on Rue Ramponeau, I have seen the disappearance of these nearby workshops, where the click of sewing machines echoed from morning to night. They have given way to the offices of architects, designers or photographers. The couture of the Sentier is very likely carried out today in what used to be called the Third World, and the Passage du Prado is rather decrepit, several of its shop fronts being closed, its activity reduced to a few African or Pakistani hairdressers.

After this passage, the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis is the centre of a small Turkish quarter, or more accurately Turkish-Kurd. In the cafés and restaurants, the vegetable stores and even the pharmacy, you find the same welcome as in the Istanbul bazaar: a whiff of the Orient just a few steps from the Porte Saint-Denis, where Louis XIV is triumphantly crossing the Rhine. The Julien restaurant, on the right-hand side, was formerly a Parisian bouillon, like the Bouillon Chartier on the Rue du Faubourg-Montmartre, or the Bouillon Racine on the Rue Racine, where you could enjoy a bouillon of meat and vegetables. In the 1970s, it was still possible to eat very well here for next to nothing, but entrepreneurs who noticed its splendid Art Nouveau décor bought the building and have developed it into a fancy restaurant. Advertisements claim that you might meet Angelina Jolie or the French actor Fabrice Luchini here.

The Faubourg then crosses two parallel streets begun under Louis XVI and continued under Louis-Philippe, the Rue de l’Échiquier and the Rue d’Enghien. No. 10 on the Rue de l’Échiquier was the site of the Concert Layol, displaying the talents of Paulus, Yvette Gilbert and Dranem, then in later generations Lucienne Boyer, Marie Dubas, and even Raimu and Fernandel. On the same side, but in a different world, a Turkish-Kurdish bookstore bears the name Mevlana, who the owner tells me was a thirteenth-century mystic. As well as many religious works, you can also find here books on the Montessori method (in Turkish) or Che Guevara.

The crossroads of the Rue de l’Échiquier and the Rue d’Hauteville has a fine outlook, in one direction towards the monumental post office on the Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière and the minaret of the Comptoir d’Escompte, in the other towards the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, which encloses the Rue d’Hauteville and what remains of its Ashkenazi furriers in an impeccable stage set.

On the corner of the Rue d’Enghien and the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis, the café Chez Jeannette has kept its fine 1950s décor almost intact. I frequented it when I used to train in a nearby boxing hall, whose décor and accessories had not changed since the era of Charles Rigoulot, the strongest man in the world, and the great Marcel Cerdan. Jeannette peeled vegetables for the evening meal with a nobility that I found very Parisian, without being entirely sure that she was not Breton or Picard. The young people who run the café today do not remember her.

‘Fine 1950s décor’ – since when did people start appreciating this style? When I was in my first year of medicine, in the frosty faculty on the Rue des Saints-Pères – this was 1955 – an old bistro on the corner of the Boulevard Saint-German was being refurbished, and we all found the new décor horrible. Today, Le Rouquet prides itself on its neon lights and Formica tops, its well-preserved ‘50s style’. We preferred at that time a café nearby, in a shack with a pointed roof on the corner of the Rue des Saint-Pères and the Rue Perronet. It was run by ‘Père Mathieu’, an old Auvergnat, who fed for free his student friends who came like him from the Massif Central, even paying for their books – which did not at all please his much younger wife, who saw her husband’s consumption of alcohol and tobacco make away with their capital. Solidarity between Auvergnats was also expressed in higher realms: places as interns or externs were always found for natives of that province in the two major neurology departments of the Salpêtrière, headed by eminences who, with a background in Action Française or its like, compensated by not accepting blacks or Jews.

The ‘30s style’ that is also much admired today (even if little represented in Paris outside of the 16th arrondissement) was despised by my parents and their friends. They could not find words critical enough for the building on the Rue Cassini where we lived – today a listed building, and quite rightly so. It is as if each generation hates the architecture and design in which it spent its youth. This fluctuation in taste is not specifically French. In Warsaw today, young people enthuse over the Palace of Culture and Science, the immense skyscraper from the 1950s that was a present from the Soviet Union, and in comparison with which the Empire State Building is a model of sobriety. Their parents detested it as a symbol of both oppression and bad taste. Éditions Hazan had a stand there at the book fair of 1990, when it was expected that the post-communist countries would become a big market. I remember old Poles who spent hours browsing through our books, each of which probably cost a month’s salary for them, in sad contrast to the luxurious interior of the building.

Will people one day find charm in Bofill’s colonnades on the Place de Catalogne, the bay windows in the Horloge quarter, or the winds of the Avenue de France? We cannot be sure. Each age has its good and its less good architecture. Bernini found the dome of Val-de-Grâce ‘a smallish skullcap for a big head’, and Ledoux made fun of the spindly columns of Gabriel’s palaces on Place Louis-XV (today Place de la Concorde).

A little after the Rue d’Enghien, the Cour des Petites-Écuries opens onto the left-hand side of the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis. Fifty years ago this was the headquarters of the leather merchants who lunched at the Brasserie Flo, where service closed at nine o’clock in the evening. The cashier had a large wolfhound, and the place smelled of the black soap used to wash the wood floor. Flo and the whole court have changed a good deal, even becoming a kind of foreign island. Elegant young people sit at the terrace tables, and the pretty young girls in their entourage have nothing in common with the motley proletarian population around them.

At the far end of the court, a narrow passage leads to the Rue des Petites-Écuries, where a cultural centre run by Turkish Maoists is adorned with posters demanding the liberation of political prisoners in several Asian countries. A few metres away, the celebrity of the street is New Morning, a great spot for jazz in Paris since the 1980s, where such glories of the trumpet and saxophone as Chet Baker, Dizzy Gillespie, Archie Shepp and many others played.

Returning to the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis, you cross the Rue de Paradis, the domain of porcelain and luxury glassware: Baccarat, Saint-Louis, Daum and Lalique have shops here, while the ancient Boulenger pottery even has a superb 1900 building whose front wall and column are topped by the curve of an immense glazed bay.

Before reaching the Boulevard Magenta, the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis widens and opens to the left onto a rectangular park that serves to provide a little chlorophyll in this mineral quarter. Behind it, the façade of a chapel built under the Restoration by Louis-Pierre Baltard (the father of the ‘Les Halles’ Baltard) is the only remaining vestige of the immense hospital-prison of Saint-Lazare. In the 1630s, Vincent-de-Paul was given a former leper colony here to train missionaries, and the mission subsequently occupied an immense enclosure between the Faubourg-Saint-Denis and the Faubourg Poissonnière. Its main building served for various purposes over the centuries, all aimed at the repression of deviants: a house of correction under the Ancien Régime, where rebellious children were locked away; a prison for sexual criminals; a political prison at the time of the Revolution (André Chénier was sent to the scaffold from here); and still a prison in the nineteenth century, for loose women as well as for many Communards, including Louise Michel. In the 1930s, the building returned to its original role as a hospital: prostitutes affected with venereal disease were treated here; pox and clap were cared for before AIDS relegated them to second place in pathology. After being closed for a long while, the hospital was recently demolished to make way for the Françoise Sagan mediathèque. The new buildings, all white and echoing the arcades of the old hospital, have an almost Mediterranean aspect, unexpected but rather agreeable, and emphasized by the palm trees swaying in the courtyard.

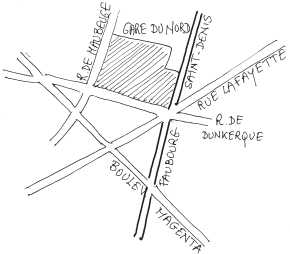

The Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis continues across two major axes, first the Boulevard Magenta and then the Rue La Fayette: two enormous crossroads followed a little further by a third, where the two axes cross one another in front of the Gare du Nord.

À Saint-Lazare, Toulouse-Lautrec.

The Boulevard Magenta and the Rue La Fayette each play the same role in the general design of the Right Bank: to join a central nerve centre – respectively the République and the Opéra – to the first slopes of the northern heights, Montmartre and Les Buttes-Chaumont. But despite this affinity in terms of town planning, the two axes are in no way similar. Any Parisian, whether by birth or adoption, and even any visitor, has the right to prefer whichever of the two they please. For my part, I sense the dynamic of the city by walking up the Rue La Fayette, whereas I avoid when possible the Boulevard Magenta. The former is the older of the two – originally known as Rue Charles X, which dates the start of this cutting. Finished much later – the bridge with concrete lattices that I referred to above dates from the 1930s – it has a great variety in terms of architecture, colour of stone, and the atmosphere of the quarters it crosses. There is nothing boring about the Rue La Fayette, whereas the Boulevard Magenta aligns Haussmann and post-Haussmann buildings with a tiresome regularity. The height is the same from the Place de la République to Barbès: five storeys with a running balcony on the top floor, zinc roofs with skylights, dark grey stone, nothing to attract the eye. The views towards the stations, the Saint-Quentin market, and the porch of the Lariboisière hospital, are not enough to brighten up this long and falsely flat avenue, difficult for the cyclist, where the most numerous shops are agencies for temporary work.

Though many Parisians are unaware of it, the large esplanade in front of the Gare du Nord has been known since 1987 as the Place Napoléon-III. Very logically, the rehabilitation of Badinguet4 began in that decade, when neoliberalism became unquestioned dogma. The shady adventurer, gang leader and author of the December massacre underwent a surreptitious mutation into the Saint-Simonian philanthropist, a pioneer of the modern banking and industrial system. This is why the municipal council, then presided over by Chirac, almost clandestinely gave Louis-Napoléon’s name to a major Paris square. Perhaps there was already enough glorification of his victories in Italy – Magenta, Solférino, Turbigo – and Crimea – Alma, Malakoff, Sébastopol, Eupatoria. (We may note that no street celebrates the disastrous Mexican expedition. Even the battle of Camarón, a great deed of the Légion Étrangère, has no street in Paris.)

I said above that the façade of the Gare du Nord was a masterpiece. It is a shame that no one stops to contemplate it, whereas crowds throng in front of the façade of Notre-Dame, whose statuary is no older than that of the railway station. This façade has three storeys, their décor composed of fluted Doric columns and statues. Metal grilles have been installed between the columns implanted on the pavement, to prevent the homeless from protecting themselves from wind and rain. Higher up, on the middle level, statues of northern cities alternate with columns – at the corners, the effigy of Douai on the Boulevard Magenta side, and that of Dunkirk on the side of the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis. The upper level is a wide pediment supported by a curved arch and framed by colossal pillars. Its ascending stages culminate with a figure of Paris. On the sides, statues represent the northern capitals – Berlin, London, Brussels, Amsterdam. These proud and elegant women, dressed in the antique style, were sculpted by artists now forgotten, but are a match for many exhibited in the Musée d’Orsay.5

Despite its attractions, the Gare du Nord has hardly been an inspiration to writers or artists. In this field, the palm goes without contest to the Gare Saint-Lazare:

those vast, glass-roofed sheds, like that of Saint-Lazare into which I went to find the train for Balbec, and which extended over the eviscerated city one of those bleak and boundless skies, heavy with an accumulation of dramatic menace, like certain skies painted with an almost Parisian modernity by Mantegna or Veronese, beneath which only some terrible and solemn act could be in process, such as a departure by train or the erection of the Cross.6

Claude Monet devoted to these glass-roofed sheds a series of twelve canvases, and one of Édouard Manet’s most famous paintings is often referred to as ‘La Gare Saint-Lazare’, even if this is only by allusion.7 The difference in treatment received by these two stations is not hard to understand: when these painters and writers left Paris to take the air, they went to Normandy, to Balbec, to Giverny, to Honfleur, rather than to Maubeuge or Armentières. Many of them lived and worked close to the Gare Saint-Lazare – Mallarmé between the Lycée Condorcet and the Rue de Rome, Manet on the Rue d’Amsterdam, Caillebotte on the Boulevard Malesherbes.

The Gare du Nord is the last station whose surroundings still recall the destination of the trains that leave from here: ‘À la Ville d’Aulnay’, ‘Au Rendez-Vous des Belges’, ‘La Tartine du Nord’, ‘À la Pinte du Nord’ – only fast-food joints and Chinese restaurants escape this spell. The Gare Montparnasse, at the time of the famous photograph of a locomotive suspended in the void, was the centre of a Breton quarter in which Bécassine8 could have felt at home. The construction of the Tour Montparnasse, the commercial centre and the new station has left only a scattering of crêperies. Around the Gare de Lyon there is scarcely any southern touch, though it is perhaps not accidental that the former Auvergnat quarter – the Rue de Lappe, the bottom of the Rue de la Roquette, where a dance hall, ‘Au Massif central’, occupied what are now the premises of the Théâtre de la Bastille – grew up around here.

Among the several brasseries opposite the Gare du Nord, the Terminus Nord used to be one of the most agreeable. It then fell into the same hands and suffered the same fate as the Bouillon Julien I mentioned above, as well as Bofinger, La Coupole and Le Balzar: standardization of menus, impersonal reception, disappearance of those peculiarities that made each of these a meeting place with its regulars, its customs, its particular dishes. Out of all of these, it is the old Balzar that I miss the most – the others, in fact, I rarely went to, least of all La Coupole, too marked by memories of Sunday lunch there with my parents. But Le Balzar’s celeriac remoulade, calf’s head and breaded pig’s feet were peerless, the waiters elegant and friendly, the globe lamps lit women in a radiant light, and sometimes, dining there after an operation that ran late, you might see Delphine Seyrig or Roger Blin coming out of the theatre. The passage of years may have embellished these souvenirs, but I could certainly find witnesses to confirm that Le Balzar was indeed an enchanting place.

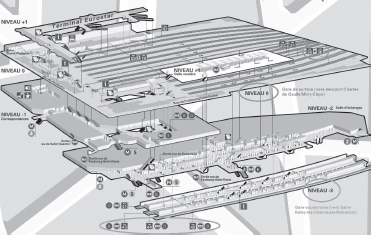

The bulk of the Gare du Nord gives an impression of unity. The recent extension, set back and in a judiciously subdued architecture, does not disturb this. But this external unity is a mask. Throughout its extent, the station is divided into three levels, one the same as the street and the others below. This demarcation is far more than simply spatial, as upper and lower no more communicate with one another than the world of the living and that of the shades did in the time of Ulysses.

Levels of the Gare du Nord, diagram displayed in the station.

The upper level is impeccable. Beneath the great glass roof the signs are clear, the seats are comfortable, a kiosk offers a choice of the foreign press, the cafés are clean and welcoming. This is where the Thalys trains leave for the northern capitals, as well as the Eurostar, protected by a security system like that of an airport. The travellers are executives, businessmen and women, tourists – white, clean, and well-dressed.

Going down, level -1 is no worse than the Châtelet station of the RER. It is the vast level -2 that needs to be seen. The ceiling is low, the colours dark, the lighting dim, the signs incomprehensible and the announcements inaudible. As there are more than forty suburban train lines, the result is a gloomy labyrinth. Those who arrive every morning and leave every evening, from Goussainville, Luzarches, Persan-Beaumont or Villiers-le-Bel, know where they are, but all others wander across the platforms looking for the train to take them to the Châtelet or out to Roissy. The population on this lower level are in great majority black. The videos taken during the station’s periodic riots show angry black crowds, yet only a few Arabs, which illuminates the difference between the two populations. The blacks, more recent arrivals and hence more fragile in status, are pushed out miles from anywhere, whereas the Arabs are well settled in the communes of the inner suburbs, Saint-Denis, Aubervilliers, Gennevilliers, accessible by Métro. As for the whites here, they are haggard tourists trying to decipher announcements as mysterious as ancient oracles, and muscular railway police whose brutality is well known to the ‘users’.

It is impossible to attempt here what Anna Maria Ortese admirably succeeded in doing in her Silenzio a Milano9 – spend the night on a bench observing the humanity that chooses a railway station as refuge amid the brutality of life. Impossible because there are no benches here.

Once you pass the station, the first remarkable point on the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis is the Fernand-Widal hospital, which until 1959 was known by everyone under the name of Maison Dubois. Antoine Dubois was a great surgeon under the Empire and the Restoration, consultant to Napoleon, obstetrician to Empress Marie-Louise and later to the Duchesse de Berry. He was director of a clinic on the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin, which moved to its present site after his death but kept his name on account of his great popularity in Paris – he also has a street named after him between the Rue de l’École-de-Médicine and the Rue Monsieur-le-Prince. The Maison Dubois was a paying establishment. In a letter to Ancelle, his family’s lawyer, Baudelaire, arranging for his mistress, Jeanne Duval, to be hospitalized there, wrote:

On 3 May [1859] I have to pay 120 francs to the clinic plus 30 francs for care. I cannot go to Paris [he was at Honfleur]. Use the Saturday (tomorrow) to have my mother cash the enclosed bill, and on Sunday send 150 francs (a 100 franc note and a 50) or a money order to M. le Directeur de la Maison municipal de santé, 200 faubourg Saint-Denis. You can say in your letter that you are sending this on behalf of M. Baudelaire for the stay of Mlle Jeanne Duval, that there is 120 francs for her stay and the 30 francs are to be handed to the patient herself for her care.

The Maison Dubois saw many writers and artists pass through its doors, including Nerval, on the occasion of one of his crises towards the end of his life, and Murger, who died there in 1861.

The front side that faces the boulevard is in no way remarkable, but the inner courtyards – designed by Théodore Labrouste, younger brother of Henri Labrouste, the architect of the Sainte-Geneviève library and the reading room of the Bibliothèque Nationale – are pleasant, the first courtyard surrounded by arcades supported by colonnades, the second planted with an avenue of maples. A younger brother’s architecture, modest and well-groomed.

It was in the Maison Dubois that I first joined the working life of a hospital. This was on the lowest rung of the ladder (‘performing an extern’s function’), but this tiny step was a qualitative leap. I found myself admitted into a territory peopled by characters of a different nature, dressed in the white coat provided by the hospital and fastened by toggles, instead of the apprentice’s coat washed at home, as well as the perspective of earning a few francs at the end of the month. It was intoxicating.

The surgical unit where I practised my minuscule functions was presided over by a disciple of Mondor, Professor Olivier: parting in the middle, half-moon glasses, bow tie, unfailing arrogance – the typical surgeon of that time. Fortunately he had assistants who struck me as well-meaning and went so far as to call me by my name, naturally in the polite ‘vous’ – the familiar ‘tu’ would only come when you passed the internship examination, a simple but decisive sign of your admission to their caste. This (and the history of the French Revolution) is very likely why I acquired the habit of calling everyone ‘tu’, except those whom I know will not reply in the same way.

The patients in this hospital were poor people from around the railway stations, French proletarians and immigrants from Italy, Spain, North Africa. The quarter was black and dirty with the smoke of the trains. Electrification had only just begun. This was the time when second-class carriages were decorated with black-and-white photographs of Bagnères-de-Bigorre, Berck-Plage or Autun, when one of the railway staff would strike the carriage wheels with a long-handled hammer to detect possible cracks, and when trains to the south stopped at Laroche-Migennes to ‘take on water’. (Evoking these images, I think of my father likewise relating memories of another time – that his teachers wore frock coats to their lectures, that it took five days to reach France from his native Egypt, and that bets were laid each night on the number of miles travelled that day.)

The faubourg had a ‘bad reputation’, as people would say in those days. I remember an emergency admission of a man with a bullet in his stomach, probably the stomach wall as he could still walk. He asked for the bullet to be removed, but refused to be registered and admitted. When it was explained to him that this was not possible, he left just as he had arrived.

We have to fear that the Assistance Publique, in its concern for profitability and standardization, will one day close this small hospital, as it has closed Boucicaut, where the nurses were still nuns when I was an intern there, the Vaugirard hospital with its fine gardens, the Saint-Vincent-de-Paul where Gilbert Huault worked, the Broca close to Boulevard Arago which specialized in skin diseases, the Bretonneau that took in poor children from Montmartre, and the Laennec, where I worked for some twenty years. It is true that these establishments were not ‘rational’. At Laennec, for example, there was a heart surgery unit – my own – but not a cardiology department; the technical level (not a phrase used) was rudimentary, and patients had to be sent all over Paris to have their eyes or their knees treated. But these small hospitals could have been improved to meet local needs instead of destroying them, selling their land to developers and replacing them with monsters like the Georges-Pompidou hospital where, as if it was not enough to be ill, you are immersed in an atmosphere that varies over the course of the day between that of an airport and that of a modern prison. Whereas the destroyed hospitals animated their area with the presence of students, nurses, visitors, the surroundings of the Pompidou hospital are more like the downtown of Phoenix, Arizona. One night I actually got lost there, and could not find anyone to show me the way back.

From the Fernand-Widal hospital to the Place de la Chapelle, the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis is the hub of an Asian quarter that grew up a good twenty years ago and today stretches into the adjacent streets – Cail, Louis-Blanc, Perdonnet. In colourful shops, amid the rich smell of spices, you can buy jewellery from junk to fine gold, saris, Bollywood films, ginger, guavas, and many other fruit that I can’t identify. Parisians often call this quarter ‘Indian’ or even ‘Pakistani’, but if there are certainly Hindi-speaking Indians as well as natives of Pakistan or Bangladesh here, the majority are Tamils. Some come from south-east India, the state of Tamil Nadu (‘land of the Tamils’), whose largest city is Madras. Others are Sri Lankan – perhaps they supported the independence war of the Tamil Tigers, preserving this memory after the horrific massacres by the island’s central government.

This fragment of Asia is one of the Parisian quarters sometimes referred to as ‘ethnic’, a word imported from America, where it means something more like exotic (‘ethnic restaurant’, ‘ethnic dress’), whereas in the French version the notion of race is scarcely concealed. Each of these quarters has its history, with highs and lows that may even lead to its complete disappearance, whether by assimilation or repatriation. I remember for example the extinction of the white Russian colony around the Avenue de Versailles. Few still remember that a Russian newspaper used to appear each week in the postwar years, for which M. Dominique, who ran a famous restaurant on the Rue Bréa in Montparnasse, wrote the theatre notes. The Spanish flavour that the Avenue de Wagram had in Franco’s last years – a time when the Parisian bourgeoisie had maids and buildings had concierges – has also disappeared, as well as the Japanese enclave along the Rues Sainte-Anne and Petits-Champs, leaving only a few gastronomic addresses.

But neither Russians nor Spaniards nor Japanese were numerous enough in Paris to form genuine quarters. On the other hand, the old Jewish quarter still exists in and around the Rue des Rosiers, though it is threatened on all sides. The Yiddish-Ashkenazi part of its population, overwhelming in the days when the Rue Ferdinand-Duval was known as the Jewish street, has gradually aged and disappeared. On the site of Goldenberg’s grocery, where I often went on Sunday mornings with my father to buy pickelfleisch and malossols, and where Jo Goldenberg greeted his customers with a broad Parisian accent unlikely in such a place, there is today a Japanese clothes shop. The quarter is experiencing converging and even combined pressures, that of gay bars and that of fashion, which are steadily gaining ground on the Rue des Rosiers and nearby, where the street names – Blancs-Manteaux, Guillemites, Hospitalières-Saint-Gervais – come straight from the Middle Ages and remind us of the religious congregations that at one time shared this region.

The Arab Goutte-d’Or, the African quarter of the Dejean market, is also under a double threat, the omnipresent one of the police and that of a gentrification that is visibly progressing, the two being as closely tied as the fingers of one hand, or as profit and violence if you prefer. By comparison, the two Chinatowns, that of the 13th arrondissement and the smaller though older one of Belleville, are prosperous and peaceful, and steadily expanding on their margins. The Chinese have even managed to create their own Sentier in the old Rues Popincourt and Sedaine, from which any trace of urban life has now disappeared under the implacable monotony of ready-to-wear. This little quarter, which was the centre of Protestantism in Paris at the time of the Reformation, before becoming par excellence the site of barricades in the nineteenth century, is now very sad. On the other hand, we can only rejoice that many tabacs have been taken over by Chinese, far more efficient than their traditional grumpy proprietors.