CHAPTER 7

The long, fascinating and magnificent Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis ends at the Place de la Chapelle: a halt as at the threshold to another world. You are facing what was one of the great gates in the Wall of the Farmers-General, today traced by the overhead Métro. (The engineers for the Métro line chose the space freed by the destruction of the wall in the 1860s as suitable for this great project.)

At the start of my journey, I crossed the Wall of the Farmers-General to enter the city at the Barrière d’Italie, but there is no symmetry here. The wall was more substantial to the north than to the south, where in some places it had not yet been completed on the eve of the Revolution, the gaps being closed by palisades or simply wooden boards. This was because goods subject to excise duty at the gates – wine, wheat and wood – arrived more from the north and east of the city than from the south. There are still signs of this in present-day Paris, where, in the bourgeois quarters and on the Left Bank, the roads that follow the line of the old wall, like the Avenue Kléber or the Boulevard Raspail, have two symmetrical sides, whereas in the north and east the inner and outer sides often remain different, creating a persisting border effect.

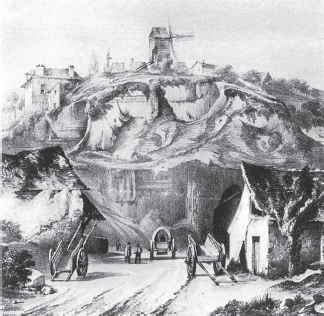

What would you find beyond this gate before the destruction of the wall, before the Paris boundary extended to the fortifications (the present-day Boulevards des Maréchaux)? One commune, La Chapelle-Saint-Denis, was arranged on a north-south axis along the ‘La Chapelle highway’ – today the Rue Marx-Dormoy then the Rue de la Chapelle. Until the 1840s this was still countryside, with vineyards (La Goutte d’Or was a white wine whose reputation went back to Henri IV), windmills, gypsum quarries and highway bars.1 The main market for dairy cattle in the Paris region was held here.

But far more than its neighbours – Montmartre on one side, La Villette on the other – La Chapelle-Saint-Denis would be transformed by the railway. The northern and eastern railways were built on its territory, occupying large expanses and chasing the vineyards and game a long way away. In ten years the commune became industrial, with workshops and warehouses, locomotive and steam-engine works, cloth printing, chemical plants, salt and sugar refineries. The population was then working-class. After the revolution of February 1848, the great works on the railway became National Workshops, with the result that in the course of the June Days (which were triggered by the closing of these workshops) the national guard of La Chapelle-Saint-Denis went over to the side of the insurrection – one of its lieutenants, Legénissel, an industrial designer, commanding the barricades on the Rue La Fayette at the corner with the Rue d’Abbeville, and giving Lamoricière’s troops a great deal of trouble.2

Railway tracks still mark the landscape of the 18th arrondissement, but those from the Gare du Nord and the Gare de l’Est are not embedded in the urban fabric the same way. The latter are bordered by streets – the Rue d’Alsace, the Rue Philippe-de-Girard, the Rue d’Aubervilliers – which include them in the landscape. The former, in contrast, are bordered by buildings that turn their backs to them, standing almost vertically above the rails. It is only possible to see the tracks, therefore, from the bridges that span them – provided that these open skies and vistas of the banlieue are preserved, and the town-planners and developers do not get the idea into their heads of gaining new space by covering over the tracks as at the Gare d’Austerlitz.

In contrast to Barbès, the Place de la Chapelle is not a crossroads dislocated and crushed by the overhead Métro. Here, the two sides of the Boulevard de la Chapelle diverge, and the space between them forms a little park. Its corners are occupied by three cafés (one of these a ‘Danton’, which must date from the centenary of 1789, like the statue at the Odéon crossroads), and the fine theatre of Les Bouffes-du-Nord. The Métro station is not located in the middle of the intersection as at Barbès – the parallel between these two neighbours, both crossed by the railway, is evident – but shifted some twenty metres further east (towards Stalingrad), allowing us to see the impeccable design of the external stairway, the care taken to connect it to the glass panels of the platform, and the bridge with its high stone pillars that support the ensemble.

The two scraggy parks between the Métro and the left side of the street have plane trees that provide shade in summer. (At the time I passed here, the one on the left – looking outward – served as an encampment for refugees, who had settled or resettled here after the police violence on the Rue Pajol.) The newspaper kiosk, against the park on the right, was formerly run by a young woman who was Arab, Trotskyist, and veiled, which is not so common. In brief, if the Place de la Chapelle can be seen, and is often seen, as a site of noise, dirt and giant traffic jams, you can also – as I do – find poetry here, and even a certain gentleness. (This is my only use of the word ‘poetry’ in this book, I promise.)

The major road that crosses the Place de la Chapelle in an almost straight line initially bears the name of Marx Dormoy, the socialist interior minister in 1937 following the suicide of Roger Salengro. (Dormoy was himself murdered in 1941 by the Cagoule, which he had not succeeded in eradicating.) This is bordered by bourgeois buildings from the late nineteenth century, by the cheap housing of a working-class banlieue, much of which is walled off, and by 1960s constructions set considerably back, which emphasizes their ugliness. (It is scarcely conceivable that we had to wait until 1977 for new buildings to be no longer set back in this way. The law that prescribed alignment dated from the Empire, and had the aim – though not the effect – of leading in time to a widening of the roads.) The population here are Arab and black (there are very few Tamils in the 18th arrondissement), poor as are the shops and cafés, not to mention the people who ask you for a cigarette. The Rue Marx-Dormoy, and still more so the Rue de la Chapelle that continues it, is a proletarian street, similar to the Rue d’Avron in the 20th arrondissement – which also runs between a former gate in the Wall of the Farmers-General (the Barrière de Montreuil) and the shambles of the Porte de Montreuil.

Soon after crossing the Rue Ordener and the Rue Riquet, the church of Saint-Denis-de-la-Chapelle and the basilica of Sainte-Jeanne-d’Arc form on the right-hand pavement a massive Catholic presence that is unexpected in such a place. These two elements, different in all respects, are united by the figure of Jeanne d’Arc, a bronze statue of whom gives life to façades that are not very welcoming. In front of this statue, a Belgian tourist who collects photos of his heroine asks me if I know of any others in Paris, apart from the one on the Rue des Pyramides that he has just visited. I tell him of those on the Rue Jeanne-d’Arc, on the esplanade of the Sacré-Coeur and the parvis of Saint-Augustin, as well as the helmeted one on the Rue Saint-Honoré, which recalls how Jeanne was wounded there by an English arrow. It was just before she led a charge against the English that she is said to have meditated here, in the church of Saint-Denis – of which almost nothing medieval remains, apart from a few capitals of the right-hand span.

The history of the adjoining basilica is a curious one. In September 1914, when Paris was threatened by the German advance, the archbishop solemnly pronounced in front of Notre-Dame the vow to erect a basilica consecrated to Jeanne d’Arc if the city was saved. After the war, the project was put into execution. Sadly, the municipal authorities rejected a design by Auguste Perre for a concrete tower 200 metres tall, which he would construct thirty years later at Le Havre. The actual construction, finished in the 1950s, has a fortress-like exterior and the interior of a concrete icebox. To see any quantity of white people in this quarter, you need to come here on Sunday at the time of mass.

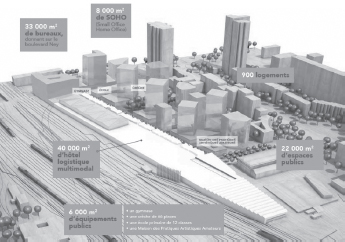

The urban fabric then steadily unravels until you reach the Porte de la Chapelle, where it gives way to an inextricable jumble of slip roads to the motorways and the Périphérique, railways in every direction, and the inaccessible tiny green spaces that I mentioned at the start of this journey. Just before this, to the left, an enormous construction site alongside the railway from the Gare du Nord is named ‘Chapelle International’. On the corner with the Boulevard Ney, a billboard gives the details of a ‘programme unprecedented in France’, christened SOHO (Small Office, Home Office): ‘To bring together activity spaces and residential spaces in a single project’, establishing ‘a lasting cohabitation between city and railway’. The images of this synthesis are frightening.

La Chapelle is divided in two both by its major north-south axis and by the railway from the Gare du Nord. On the Boulevard Barbès side, as far as the very old Rue des Poissonniers, which is where seafood arrived in Paris from Boulogne before the building of the railway, you have La Goutte-d’Or. This extends beyond the Rue Myrha (named after the daughter of a mayor of Montmartre, rather than Myrrha, daughter of the king of Cyprus whose tribulations Ovid relates in his Metamorphoses) up to the Porte des Poissonniers, a quarter that is nameless but not without character. On the other side, to the east as far as the Rue d’Aubervilliers, is a zone now rapidly changing, where on each visit you find new depredations. Communication between these two halves of La Chapelle is reduced, as there are only three bridges where the railway can be crossed, on the Rue de Jessaint, the Rue Doudeauville and the Rue Ordener. The two regions thus remain different in every respect, and even foreign to one another.

© A.U.C.

Boulevard Ney, billboard for the Chapelle International project.

For a long time, La Goutte d’Or was a foothill of Montmartre, a hill where gypsum was extracted, partly open-cast and partly in quarries such as the one Nerval evokes in October Nights, which ‘resembled a Druidic temple with its tall pillars supporting square-shaped vaults. You looked down into its depths, almost afraid that the awesome gods of our ancestors – Esus, Thoth or Cernunnos – would emerge into view.’3 On the surface, between the vines, five windmills used to turn at the mouths of the ovens to mill plaster, an indispensable material in ‘this illustrious valley of rubble constantly close to falling, and of streams black with mud’, as Balzac writes at the start of Old Goriot.

As far as the present Goutte-d’Or is concerned, a kind of confusion or superposition is often made between it and Barbès. It is true that La Goutte-d’Or is bordered on two of its sides by the Boulevard Barbès and the Boulevard de la Chapelle, but these are borders that might be called external. Barbès is a bazaar in the original sense of the term: everything can be found here, which is not the case with La Goutte-d’Or. At the start of the present century, I lived on the Rue de Sofia, a small side street that comes out into the Boulevard Barbès opposite the Rue de la Goutte-d’Or. In the dozen or so years since then, the things sold in the bazaar have changed a bit: suitcases are slower to move, mobile phones much quicker, while jewellery and cut-price goods go much the same. The most striking development is the gentrification of Barbès, which is far more marked than that of La Goutte-d’Or. Its most obvious signs are the renovation of the Le Louxor cinema (which it would be foolish to complain about), and above all the establishment of a luxury brasserie on the corner of Boulevard Barbès and Boulevard de la Chapelle. Implanted on the site of a cut-price goods store that burned down – its ruins were used as a platform at the time of the banned demonstration against Israeli intervention in Gaza in July 2014 – this establishment is not only an offence to the spirit of the place, but also a kind of test: how far can you go before ‘those people’ start to break everything?

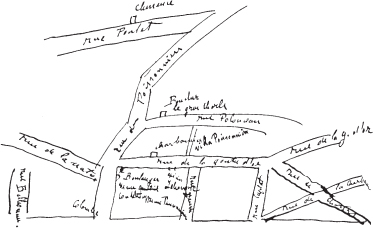

I do not know when La Goutte-d’Or became the quarter of Paris’s Arab wholesalers, and Barbès a bazaar for suitcases and contraband cigarettes. What is certain is that the Algerians who settled here made a bad choice, the district having now been for a long time one of the poorest and most neglected in the city. It was so even before the cutting of the Boulevard Barbès and the Boulevard Magenta shifted the old crossroads, in the days when the Rue des Poissonniers and the Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière met at the barrière, when, at the start of Zola’s L’Assommoir, Gervaise’s eyes ‘persistently returned to the Barrière Poissonnière, watching dully the uninterrupted flow of men and cattle, wagons and sheep, which came down from Montmartre and from La Chapelle’. From her window in the Hôtel Boncoeur (‘on the Boulevard de la Chapelle, at the left of the Barrière Poissonnière, a two-storey building, painted a deep red up to the first floor, with disjointed weather-stained blinds’), she looks out into the night for the return of her lover, Lantier:

She looked to the right toward the Boulevard de Rochechouart, where groups of butchers stood with their bloody frocks before their establishments, and the fresh breeze brought in whiffs, a strong animal smell – the smell of slaughtered cattle. She looked to the left, following the ribbon-like avenue, past the Lariboisière hospital, then being built. Slowly, from one end to the other of the horizon, did she follow the wall, from behind which in the night-time she had heard strange groans and cries, as if some fell murder were being perpetrated. She looked at it with horror, as if in some dark corner – dark with dampness and filth – she should distinguish Lantier – Lantier lying dead with his throat cut.

A magnificent passage, which sets the date of the narrative. The Hôpital du Nord acquired its present name when the Comtesse Lariboisière financed the completion of the works, around 1850. The last shots of the June Days of 1848 were fired on the construction site, where Coupeau, Gervaise’s new lover, worked as a plumber. I think of all this in seeing the landscape pass between La Chapelle and Barbès, against the characteristic metallic scraping sound of the overhead Métro. It seemed to me at one time that Zola exaggerated, that from a second storey on the Boulevard de la Chapelle you could not see at the same time both the hospital and the slaughterhouses (where the park on the Place d’Anvers is now). But checking from the discount store, Tati, he was right.

Some more here about those June Days. The street outside the façade of the Saint-Bernard church in La Goutte-d’Or is the Rue Affre, after the archbishop of Paris killed at this time. The street adjacent to the Saint-Joseph church, on the Rue Saint-Maur, is named after Monsignor Darboy, another archbishop, shot during the first week of the Commune. The first of these streets is close to Lariboisière and the second to Père-Lachaise, both places where insurgents were massacred in the final hours of these events. By remembering these dignitaries of the church in such working-class districts, the notables of the Third Republic probably sought to bring home to the survivors and their descendants the full horror of these crimes, and to spell out what would await them in the case of recidivism.

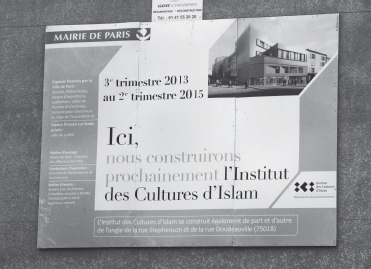

I owe my knowledge of La Goutte-d’Or to the last authentic representative of Belgian surrealism, Maurice Culot. It was he who introduced me to this quarter in 1984, when he was working on his great book on the subject.4 He showed me the traces of streets in a St Andrew’s cross (a flattened ‘X’), creating gentle slopes, dispensing with steps, and giving buildings on street corners a bevelled edge – particularly noticeable at the corner of Rue de Chartres and Rue de la Charbonnière. He took me around all the sites of L’Assommoir, which were already demolished or in the process of demolition – the café of Old Colombe that gave its name to the book, the Rue des Islettes where Zola located both Gervaise’s home and the washhouse where she worked. Above all, he explained to me the absurdity of the development now under way, the thin concrete colonnades, the unnatural levelling of the hill, the faults of alignment, the amputation of acute angles. Nothing has been settled since that time. A police station has been implanted in the middle of the Rue de la Goutte-d’Or, reputedly one of the most brutal in Paris. The Rue des Islettes has been ravaged, and is now bordered on one side by a hideous primary school above an underground car park, and on the other by a post office in front of which is a wasteland that, with consummate if involuntary irony, has been given the name ‘Place de l’Assomoir’. The mosque, on the corner of Rue Polonceau and Rue des Poissonniers, was demolished in 2013. There is a plan to build on this site an Institut des Cultures d’Islam, which will probably be as deserted as the one that already exists on the Rue Stephenson. Between the Rue de la Goutte-d’Or and the Rue Polonceau, a gloomy stairway has been constructed and named after Boris Vian. Poor Boris; what sins did he have to expiate to be given this place out of thousands of others? On the Rue des Gardes, the Paris municipality has implanted a row of fashion shops, ‘creators’ for whom the term ‘out of place’ would be insufficient; ‘obscene’ is a better term. Not that the poor are not entitled to dress themselves nicely – but to exhibit dresses worth a fortune in such a place!

So, is there still any reason to visit La Goutte-d’Or? Yes indeed, as it has, like the Noailles market in Marseille, the atmosphere of an Arab city with its liveliness, the smell of spices, the warm reception, the gentleness – regarding this word, which goes against everything that is said and written at the moment, I recall an event that dates from the time when I lived on the Rue de Sofia. One Sunday morning, I was walking with my daughter Cléo, then two years old in a pushchair, when an old Algerian came up to me on the Rue de Chartres, leaned down and kissed her hand. That sums up the whole charm of La Goutte-d’Or.

It was with L’Assommoir that Zola made his entry as one of the great writers of Paris, all of whom were in their way walkers. Zola himself walked with pencil and notebook in his hand, taking notes and making sketches. Balzac ran right across Paris, between his printers, his coffee dealers, his visits to houses to find a dwelling for ‘the Foreigner’, Madame Hanska. Sometimes he walked at random, scrutinizing shop signs in search of the name for a character (I have quoted elsewhere the passage in which Gozlan tells how he was dragged, exhausted, through the ‘Rues du Mail, de Cléry, du Cardan, du Faubourg-Montmartre … and the Place des Victoires’, until on the Rue du Bouloi, Balzac finally found what he was looking for: ‘Marcas! What do you think? Marcas! What a name! Marcas!’5). Was this also how, by walking, he found names so fitting that they became types: Nucingen, Rastignac, Gobseck, Birotteau? As for Baudelaire, who had nothing at home – when he did have a home – it was in the street that he worked. He says as much at the start of his poem ‘Sun’:

I go alone to try my fanciful fencing,

Scenting in every corner the chance of a rhyme,

Stumbling over words as over paving stones,

Colliding at times with lines dreamed of long ago.

In the twentieth century, those for whom Paris is not a back-cloth but a theme, from Carco to Breton, Calet to Debord, have also been great walkers. Proust is a special case: he did not stroll through the city, perhaps on account of his ‘suffocations’, perhaps because it was not his subject. Apart from the gardens of the Champs-Élysées and the Bois, he describes it only rarely. The passages from The Captive, when he gives us notes on the city as precious as on some Norman church, are drawn from the moment of awakening, in the bedroom where the shutters are still closed. There are sounds which make it possible to divine what the weather will be (‘according to whether they came to my ears deadened and distorted by the moisture of the atmosphere or quivering like arrows in the resonant, empty expanses of a spacious, frosty, pure morning; as soon as I heard the rumble of the first tramcar, I could tell whether it was sodden with rain or setting forth into the blue’); or else the cries of street sellers, such as the snail merchant:

For after having almost ‘spoken’ the refrain: ‘Who’ll buy my snails, fine, fresh snails?’ it was with the vague sadness of Maeterlinck, transposed into music by Debussy, that the snail vendor, in one of those mournful cadences in which the composer of Pelléas shows his kinship with Rameau: ‘If vanquished I must be, is it for thee to be my vanquisher?’ added with a singsong melancholy: ‘Only tuppence a dozen.’6

After this passage, all the more digressive in that Proust had probably never heard anyone mention La Goutte-d’Or, unless he had read L’Assommoir, I cross the Rue Myrha and enter a different quarter. Rue Doudeauville, Rue de Panama, Rue de Suez, the colours of fabrics, the hairdressers, the restaurants, the wholesalers offering fresh produce from Congo-Kinshasa, the market on the Rue Dejean where you can find all the fish of the Gulf of Guinea (Nile perch, tilapia, thiof, sompate, plas-plas). This is a corner of Africa, different from the Rue du Château-d’Eau and its hairdressers, but just as animated and joyful. Crossing from one world into another, at the corner of the Rue Labat, my thoughts turned to Sarah Kofman, a philosopher who wrote the finest book on the life of Jews in Paris under the Occupation, Rue Ordener, rue Labat – the finest along with Quoi de neuf sur la guerre? by Robert Bober, which takes place around the Cirque d’Hiver.7

Continuing on the Rue des Poissonniers after the Rue Ordener and the Marcadet-Poissonniers Métro station, I pass into a ‘normal’ and rather unpleasant quarter. In the past it was saved by the view over the roofs of the repair workshops of the railways from the Gare du Nord, humped like the backs of prehistoric animals. These workshops have disappeared. Where are sick locomotives repaired today? Perhaps the very idea of repair as we used to understand it is obsolete, and a technician with a computer notes a defective sensor which is replaced in two minutes. And with something more serious, such as an axle, a problem with the suspension, the engine is just left to rot in a corner. On the site of these workshops, in any case, there are now large buildings that block the view, storage spaces and food wholesalers. This side of the Rue des Poissonniers is a place where one day students of architecture will be shown how far commercial vulgarity and tack could go in our age.

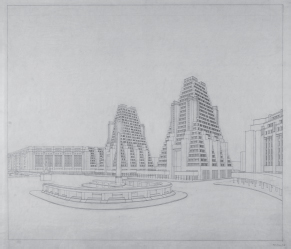

There is however a reason to make the journey to this remote corner, as it contains, almost hidden, one of the finest Paris constructions of the twentieth century: the Henri Sauvage building on the Rue des Amiraux (a name given in homage to the role of the navy in the defence of Paris in 1871). This is more than a building: a rectangular block clad with white tiles, a tall succession of stepped terraces, corners rounded into quasi-towers, openings arranged in a rigorous variety, a perfect symmetry between the two sides, in short, a miracle of invention and grace. To the side is an indoor swimming pool, entered beneath an exquisitely designed glass canopy on which a few touches of blue tiling accentuate the overall whiteness. This masterpiece is as good as the building also designed by Sauvage on the Rue Vavin, which is better known, since Montparnasse is more visited. It is a great shame that Sauvage’s plan for the Porte Maillot was not accepted – two immense stepped pyramids that would have framed the entrance that the west of Paris lacked.

The Rue des Poissonniers ends up at the porte of the same name, which is what Marc Augé – my friend at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand for several years before going on to become a famous ethnologist – would call a non-place.

To head north from the Place de la Chapelle, I could take a different route, zigzagging between the Marx-Dormoy–La Chapelle axis and the railway from the Gare de l’Est through the Rue Pajol, which leads to a micro-quarter centred on the market on the Rue d’Olive (named after the first governor of Mauritius). A few years ago, the covered markets of Paris were the object of an offensive by the municipal authorities that aimed to make them into ‘cultural spaces’, ‘sports spaces’, ‘gastronomic spaces’ or the like. After the Enfants-Rouge – one of the last places where you hear Yiddish spoken in Paris, which has been totally denatured if not destroyed – the Secrétan market, and the ancient Carreau du Temple, which you could believe was forever devoted to leather and velvet, likewise saw their metal and glass structures ravaged, and their activities, so useful and Parisian, become those of the mall of a small American town. The Rue d’Olive market has happily preserved its buildings and its original activity. The streets around it are calm, bordered by the working-class housing of the nineteenth century that is the connective tissue of La Chapelle. In other words, this is ‘an agreeable corner’, and as is usual in such cases, subject to a process of embourgeoisement – a term rather more accurate than ‘gentrification’, as there are no signs that ‘gentry’ have anything to do with this typically petty-bourgeois phenomenon.

© SIAF/Cité de l’architecture et du patrimonie/

Archives d’architecture du XXe siècle

Henri Sauvage’s plan for the Porte Maillot, 1931.

Here this process is still in its beginnings. The context has not changed, just the population. Alongside the Chinese, Arabs, and poor people from all origins who still populated this quarter ten years ago, young white people have now moved in – not that well off, but as sophisticated as in Belleville or Aligre, with their dress codes, pushchairs, trainers, hairstyles and iPads. We know the rest from having seen it appear and spread in Bastille, Oberkampf, Gambetta, Rue Montorgeuil, along the Canal Saint-Martin. Cafés proliferate, become restaurants, and on sunny days their terraces spread together in a seamless tablecloth, hosting young people so uniform that they might be cloned. Organic groceries are opened, delicatessens, Japanese restaurants. Then the old shops, shoe repairers, stationers or Arab patisseries, lower their shutters, and when these reopen, they are transformed into art galleries. Behind the works exhibited, files are stacked on shelves and young people tap on their computers. No one enters or leaves, no one stops to look, it’s a sign of the death throes of a working-class neighbourhood.

As a petit-bourgeois who has lived for over thirty years in quarters that have been gentrified one after the other, I can appreciate the contradiction in describing critically a phenomenon that, whether I willed it or not, I ended up being involved in. You would have to move home periodically, or settle a long way out, to avoid this threat for good and all.

Starting from the Rue d’Olive market, the Rue de l’Évangile leads towards the star of the Place Hébert (after a former mayor, and not the ever unjustly slandered Père Duchesne). It then describes a long curve between the railways from the Gare de l’Est on the right, and on the left the enormous Cap 18, a business park for small companies – photogravure, printing, cabling, carpentry, glass works – under an architecture that has the merit of a low profile. Until the late 1950s, this space was occupied by a tight cluster of gasometers, tall black cylinders often photographed by the big names of the time.

Where the Rue de l’Évangile comes out into Rue d’Aubervilliers there is a calvaire that gave its name to the ‘Rue du Calvaire-de-l’Évangile’. This street disappeared long ago, but the large bronze Christ is still there, more exotic in the modern landscape than it was against the backdrop of the gasometers. I had stopped in front of the statue when an old man in a djellaba, wearing the flat cap of pious Muslims, deposited on its plinth two candles contained in those small aluminium holders sold in supermarkets and churches, and proceeded to light them. Turning round, he saw my surprise and said to me softly: ‘I believe in all the gods, all the gods are good and just.’ And this polytheist hobbled off on his way.

Reaching the Rue d’Aubervilliers, I was lost for a moment. I no longer knew where I was, unable to recognize the familiar Porte d’Aubervilliers, a little roundabout where, as I remember, the Boulevard Ney continued without a break into the Boulevard Macdonald. Straight ahead, instead of the narrow Avenue de la Porte-d’Aubervilliers was a wide road bordered by recent new buildings. In particular, to my right, what I finally identified as the Boulevard Macdonald was quite new and amazing. Hoardings explained this apparition: the Calberson warehouses, which since had the 1960s stretched between the Porte de la Chapelle and the Porte de la Villette, have been completely transformed in this segment of the boulevard – transfigured and transmuted.

It was the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), the agency of Rem Koolhaas, that took charge of this major project. Its idea was to keep the footprint of the old warehouses, with an interrupted motif for more than 600 metres in the form of a metallic grille between two bands of concrete, at what would normally be the second-floor level. Even at its only break, in the middle of the block, the pattern continues as a bridge above the tramlines. Aligned on this basis are modules designed by each of the project’s fifteen architects. The first level, less high than the others, is set back, so that the modules are slightly cantilevered. They are joined together, aligned and of the same height, but the design, the width and the colour are different. Some of them are offices, others housing, others again storage units. The design was given freer rein at the two ends: facing the Porte d’Aubervilliers, the Portzamparc module is distinguished by its orange colour and the stilts on which it rests; towards the Porte de la Villette, where all the public services are congregated – school, college, sports hall – the Kengo Kuma agency designed opposite the Canal Saint-Denis a large module to which an asymmetrical double-sloped roof, and an oblique salient above windows like two round eyes, give a Japanese touch. This feat of urbanism may lack imagination, but all the same, the ensemble is superior to anything else built today in this sector.

© René-Jacques. Ministère de la Culture–Médiathèque

du Patrimonie/Archives d’architecture du XXe siècle

Gasometers and calvary, Rue d’Aubervilliers.

Opposite, between the Boulevard Macdonald and the Périphérique, on the site where the Claude-Bernard hospital was demolished in the 1990s, a new quarter is being constructed, in which certain buildings are debatable – the cinema and the school in particular – but which as a whole is well articulated and avoids the mistakes committed beside the Bibliothèque de France, where wide avenues are open to the winds. The Périphérique itself, bordered by an anti-noise barrier and a clump of trees, is crossed by a pedestrian bridge leading to Aubervilliers – the gleaming summit of Le Millénaire, a new shopping centre, emerges above the flow of vehicles. This is a lively quarter, the cafés on the boulevard are welcoming, and the population, which is not uniformly white, seems to have properly taken possession. In short, for once, ‘it was not better before’, when the Boulevard Macdonald was a desert crossing between the warehouses and the Claude-Bernard hospital.

This hospital was very familiar to me from my work as a surgeon. It stretched across a long strip of ground, from the Porte d’Aubervilliers to the Canal Saint-Denis. Devoted to the treatment of infectious diseases and tropical pathologies, parasitic and others, it dated from the early twentieth century, when the idea of contagion was prevalent everywhere, so that it was made up of pavilions of a vaguely colonial architecture, each a long way apart from the others so that miasmas could not spread – to stop diphtheria patients from catching malaria, or those with smallpox catching sleeping sickness. Around 1970, a resuscitation unit was established there, staffed by excellent doctors – such as my friend Claude Gibert, whom I knew there as my young senior registrar, capable of laughing at everything while taking everything seriously, to the point of spending his days and nights among the respirators, electric syringes and monitors. In the unit where I worked, at the Laennec hospital, when a patient being operated upon was found to have an infection, we transported them to Claude-Bernard, where they would be better treated with no risk of contaminating the other patients. And I went there – we went there – almost every day to see how the case was developing and discuss the treatment with Gibert and others. Thirty or forty years later, these memories are both good and bad. Good, as the Claude-Bernard team was remarkable, with no swollen heads, no imposed morality, nothing of the subtly distilled contempt that doctors often exhibit towards surgeons. Bad, since often, despite all the care given, the infection won out, and to lose a patient in these conditions was particularly intolerable. My memory as a surgeon, in fact, contains more failures than successes, which is quite normal: simple consequences were by far the most frequent, and there is hardly any reason to remember those patients, whereas among the others there are some that remain as silent reproaches in a corner of my memory.

© Cléo Marelli. Architect: Kengo Kuma & Associates

New buildings on the Boulevard Macdonald.

Returning west along the Boulevard Ney, this long segment of the Boulevards des Maréchaux was Jean Rolin’s theme in La Clôture,8 a book that gives in parallel the story of Maréchal Ney and a precise and often comic description of the boulevard that bears his name and the characters to be found there. At the start, there is the matter of the Bichat hospital:

If you stand with your back to the counter of the Au Maréchal Ney café, at the Porte Saint-Ouen, and look outward from Paris, you can see that the entire northeastern quarter of the crossroads is occupied by the Bichat-Claude-Bernard hospital, whose more modern and taller buildings are located on the edge of the Périphérique, and its older ones along the Boulevard Ney. On this side, the hospital wall, clad with bricks of a dirty yellow colour, and with openings that are scarce and protected by grilles, offers a forbidding spectacle.9

Among these openings, there is one, on the first floor, that was the window of the intern on surgical duty in the 1960s. As it overlooked the exit from the underpass of the Porte de Saint-Ouen, and given the intense night-time lorry traffic of that time (Les Halles!), there was no question of sleeping after night duty, when the inflow of patients finally calmed down.

In 1961, I was an intern here in the unit run by César Nardi. He was a good-looking man, an excellent surgeon, a grand bourgeois though not anti-Semitic, which was rather rare at that time and in that milieu. (When I decided to train as a surgeon, I was told that there was not a single Jew among the hospital surgeons of Paris. But this was not quite correct: José Aboulker, head of the neurosurgery unit at the Beaujon hospital, was not only a Jew but also a communist. His heroic role in the liberation of Algiers in 1942 had brought him such prestige that the caste was forced to accept him.)

© Cléo Marelli

Staff-room window of the Bichat hospital in the 1960s.

César Nardi was an enthusiastic golfer. One day when he was helping me with my first gastrectomy (which consists in removing all or part of the stomach), and having begun late we were still only at the preliminary stage, he said to me at the stroke of midday: ‘Hazan, the Canada Cup has started, I have to leave you.’ So I ended the operation with two young externs. In the post-operative care, I would go and see this patient three times a day, as it seemed to me so miraculous that I had completed the necessary procedure satisfactorily. This man, a local sculptor, was so grateful for this attention that after his discharge he presented me with his two favourite pieces, a deer’s head and a bust of Beethoven.

We were then in the midst of the Algerian war, and the Bichat hospital often received patients with bullet wounds, sometimes from the police and sometimes from shoot-outs between FLN and MLA militants. In the unit, the sister in charge of the daytime team had the Algerian patients brought down to the basement the day before their operation, where the monitoring and care were extremely poor. When I was on duty, I had them taken back upstairs, so that one day Nardi asked me why I gave preference in his unit to North Africans. I asked him to accompany me to the basement, where he would not usually go, and he backed up my decision.

It is not easy to describe what a public hospital was like in a quarter such as Bichat in the early 1960s. In the afternoons, no doctor or qualified surgeon would be present, since they were all at their offices ‘in town’, or in their clinics. Admissions and operations were the responsibility of two interns, one medical and one surgical. For general anaesthetic you had to obtain telephone authorization from one of the two duty surgeons for the whole of Paris, who would be in the process of operating at Passy or Neuilly, and who always gave their blessing – in a friendly and casual manner – except in the case of a minor, when one of them had to be present, most often remaining in plain clothes at the door of the operating theatre. The outdated premises were more than full. In winter, at Bichat, black drapes were hung on the chapel walls and stretchers piled up there for the patients admitted at night – all pathologies and ages mixed together. No one found any cause to complain, they were all poor.