CHAPTER 8

I do not know of any other capital city where the transition from inside to outside is as marked as it is in Paris. In London, Tokyo or Berlin – not to speak of Cairo or Mexico City – it is none too clear where the boundary falls, and the very distinction between the city and its surroundings is vague. There are two main reasons, I believe, for the sharpness of the boundary in Paris. The first is the existence of the portes. In earlier times these had an evident material existence, when they were openings in the fortified wall. But even after the destruction of the fortifs in the 1920s, even without gates and officials, these are not places that you cross without being aware of it. They are dislocated spaces where you can expect to find the starting points of bus routes (with three digits instead of the two for those inside Paris), petrol stations and car washes, trams, signs indicating nearby destinations – Drancy, La Courneuve, Enghien – or distant ones, Melun or Lille. The original meaning of porte has not been eradicated.

The second element that makes the limits of Paris so clear-cut is the Boulevard Périphérique, far more so than the Boulevards des Maréchaux, which without the Périphérique would eventually have been digested, including their thin belt of social housing from the 1920s, built as the city continued its centrifugal growth. The Périphérique, with its wide footprint, its anti-noise barriers, its slip roads, and the new buildings that reinforce it with an almost uninterrupted strip of corporate ugliness, is something else again. At the time of its construction, there were not many people who predicted that this road, mawkishly christened a ‘boulevard’, would constitute a terrible barrier between the old Paris and what might become the new. Louis Chevalier, one of the clearest minds of the time, describes a number of urban catastrophes in L’Assassinat de Paris – Maine-Montparnasse, the Italie quarter, La Défense, the massacre of Belleville, and of course Les Halles1 – but if I am not mistaken, he has nothing to say about the Périphérique. Nor does Guy Debord mention it in Panegyric, published twenty years after its inauguration by the happily forgotten Pierre Messmer; according to Debord, ‘this city was ravaged a little before all the others because its ever-renewed revolutions had so worried and shocked the world’.2 The only person, I believe, who understood what was happening, was Jean-Luc Godard. In 1967, in Two or Three Things That I Know About Her, his description of the Paris in which Marina Vlady wanders – juke-boxes and pinball machines in the cafés, dark green cups with gold bands, Citroën Ami 6’s and Peugeot 404’s, France-Soir and the Vietnam war – is shown in a clashing counterpoint with shots of the works on the Périphérique, where the movements of cranes, concrete mixers and bulldozers are emphasized by sudden loud and almost painful sounds, bringing home the seriousness of the threat.

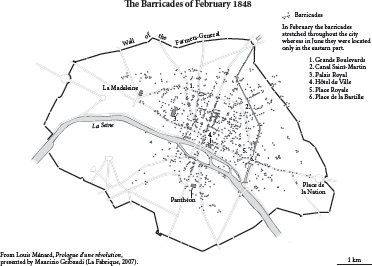

The barrier imposed by the Périphérique is not only physical, it also affects the representation of the city. By confining Paris to the twenty arrondissements, it contributes to the image of a city that is mummified and museum-ified, in which working-class life is reduced to a more or less narrow sector, confined to the north-east between Montmartre and Charonne. But as this walk has confirmed to me, such an image is completely false. From Châtelet to the Porte de la Chapelle, in the heart of the historic city, the quarters I have crossed remain largely working-class. It is true that the pockets of gentrification are tending to expand, but this phenomenon still remains limited, even marginal. Whether in the Saint-Denis quarter, around the railway stations, along the faubourg and in the long valley of La Chapelle, the city I have walked through is a working-class one. Perhaps I more or less consciously chose my itinerary for this reason, and maybe my view would have been different had I started from the Rue Montmartre or the Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière. But the fact that central and eastern Paris are largely working-class districts is not a recent phenomenon, as is well shown by the map of the barricades erected in the time of the June Days of 1848.

To classify quarters as ‘working class’ or not is a dichotomy that may fail to recognize the grey zones, encroachments, advances and retreats that shift from week to week. In the extreme case – the Rue des Francs-Bourgeois or the Rue de Verneuil on the one hand, the Rue d’Avron or the Avenue de Flandre on the other – the diagnosis is clear. But is the Place de la République, for example, working class? Yes and no. No, since almost all the cafés, shops and restaurants belong to chains, and what goes on there no longer has anything in common with the working-class life in which people meet their friends in such places or can chat with the owner. And yes, as the women and men who cross the square on foot, on bicycle or on a skateboard are a representative sample, varying according to the time of day, of the people of Paris. (Compared for example with the Place Saint-Germain-des-Près or the Place des Vosges, where, apart from tourists, the population represents a homogeneous and minority share of the human beings living in Paris.)

Despite all legitimate qualifications, there are certain markers to the working-class quarters. The Métro stations are dilapidated, the passages dirty, the escalators often broken and the exits equipped with anti-fraud systems that are unknown at La Muette or Franklin-Roosevelt. The police presence is constant and visible, showing that the object is to keep the poor quiet rather than to protect the rich. Bank branches are few and far between – just one, if I am not mistaken, along the long axis of La Chapelle, a Crédit Lyonnais so old that you can still see on its façade the date ‘1863’ when the bank was founded. On the other hand, there are many shops where you can send money to what used to be called the Third World. Others offer phone calls at unbeatable prices, or offer to ‘unlock’ your mobile. The supermarkets are ‘super-discount’, Leader Price or Dia rather than Monoprix. The cafés are Kabyl, the tabacs are Chinese, and the PMU betting shops always packed. On Wednesdays, groups of children set out on excursions, and whites are a minority in their multi-coloured ranks. And you can see in these quarters something that is for me the very symbol of sadness – an old Algerian worker alone on a bench with his imitation fur cap, his moustache and walking stick, or an elderly woman with swollen ankles, hobbling while she carries her shopping with difficulty in plastic bags.

The Boulevard Ney is so long that it borders on three adjacent communes – Saint-Denis in the centre, Saint-Ouen to the west and Aubervilliers to the east. To reach Saint-Denis, the end of this walk, several routes are therefore possible. You can follow the banks of the Canal Saint-Denis, in a dilapidated industrial landscape that crosses Aubervilliers, becoming residential when you pass into Saint-Denis, and even fashionable in the sector after the Pont du Landy: small white houses, clean surroundings, a well-kept landscape. Those living here are likely to be managers working close by in the newly built office blocks of the Plaine Saint-Denis.

Crédit Lyonnais façade, Rue Marx-Dormoy.

Another possible path is to leave Paris by the Porte de Montmartre or the Porte de Clignancourt, cross the Foire aux Puces and then old Saint-Ouen obliquely towards the mairie. By avoiding major roads, this itinerary is full of charm, the streets are calm, bordered by low buildings with ‘villas’ here and there, cul-de-sacs in which each house has a garden. The Paris banlieue has dozens of quarters like this, from Clichy to Montreuil, Vanves to Gentilly. If the ‘Grand Paris’ project ceased to be a subject of political gestures, these pleasant enclaves could be taken as the starting point, instead of which they become islands in a sea of brutal ugliness.

After the mairie, you cross the Rue du Landy, a long transversal stretching from the Pont Saint-Ouen to Aubervilliers, whose name recalls that in the Middle Ages it was in these surroundings that the largest fair in the Île de France, the fair of Le Lendit, was held. A little further along is the Carrefour Pleyel, named in memory of Ignace Pleyel, a pianist and composer, pupil of Joseph Haydn, who founded a piano factory here in the early nineteenth century – both Chopin and Liszt used his instruments. Despite this noble origin, the crossroads has been dislocated by new constructions that seem thrown down at random – the central roundabout, moreover, is not round, and has no definable shape to respond vaguely to its surroundings. The ensemble is dominated by the Tour Pleyel. I belong to the probably rather small group of those who like this tower, its slight tapering, its rigorous metal curtain wall, its empty floor below the top and even the enormous and more or less elliptical advertising sign that rotates on top and at the moment vaunts the merits of Kia, the Korean car manufacturer. Today the metal is painted white, faded slightly grey by the weather, and is fine like that.

To reach Saint-Denis, I have chosen the simplest itinerary, the straight line along the A1 motorway starting from the Porte de la Chapelle. The first few metres are rough going, and only a few pedestrians chance to take the narrow path misguidedly named the ‘Avenue de la Porte-de-la-Chapelle’. On the right is ‘the bowling alley that occupies the ground floor of the multi-level car park wedged between the Périphérique, the motorway junction, the Boulevard Ney and the railway tracks cutting this diagonally’, a passage from La Clôture that well evokes the crushing of walkers beneath a series of bridges between which the view of the sky and the open air are so narrow that they advance in a tunnel of concrete and metal.3 To the left, I can see what used to be called the La Chapelle rubbish tip, now adorned with the sign CVAE (Centre de Valorisation et d’Apport des Encombrants): pyramids of debris, green lorries, black workers.

Once the last bridge is passed – the connecting slip road from the motorway to the westbound Périphérique – I continue parallel with the autoroute, covered after the first kilometre by a landscape improvement that was entrusted in the 1990s to Michel Corajoud, who also created the pleasant Jardin d’Éole that borders the Rue d’Aubervilliers. The plantations and street furniture manage to liven up a bit this endless straight line that bears the name Avenue du Président-Wilson, interspersed with car parks and ventilation shafts for the autoroute beneath. The gardeners have left room for vegetation, with a mixture of nettles and weeds. In short, the worst has been avoided, which is certainly not easy. On both sides of this ‘avenue’ is a sad and dilapidated banlieue, with a multi-coloured but mainly black population.

All this suddenly changes once you cross the Rue du Landy. With the Stade de France, new office blocks housing the headquarters of big companies, SFR and SNCF, Bouygues and Matmut, a good part of the stock-exchange top forty installed in steel and tinted glass, this is the most striking architecture of the moment. The population are no longer the same, they are well dressed and you even hear English spoken. In the adjacent streets, instead of kebab shops and ruined warehouses, a line of luxury apartments stretches as far as the eye can see – an amazing transformation of the Plaine Saint-Denis which, after long having been the domain of heavy industry, was the very symbol of misery in this department only a short while ago. Be reassured, it has simply been pushed a bit further out.

At the end of the Avenue du Président-Wilson, the horizon suddenly widens. With the elevated curve of the A1 autoroute which turns eastward, the saucer on spikes of the Stade de France, the Canal Saint-Denis below forming a wide basin and the old town of Saint-Denis just close, this little hill creates a kind of frontier effect. To emphasize this, the apartment block that disfigures it should be pulled down and a monument erected in its place, for which Alexandre Vesnin or Erich Mendelsohn could be resurrected. This would emit invisible waves directed at the Tour Pleyel in one direction and the Saint-Denis basilica on the other, which has the only tower in the old town centre.

In reality, to get from Paris to Saint-Denis, almost everyone takes the Métro – line 13, the most neglected, the most irregular, always packed in its proletarian sector between Saint-Lazare and its northern destinations, Aubervilliers and Gennevilliers. Emerging from the Basilique station, the quarter resembles the centre of Ivry, which is understandable as it was built by the same architect, Renée Gailhoustet. The result here is a little less convincing, even if we find the same raw concrete, acute angles, planted terraces and overhead passageways that give its Ivry counterpart its charm – most likely because this development is smaller and more dense, and the choice to build everything on stilts creates dark corners that are scarcely welcoming.

© Artedia/Leemage

Einsteinturm, Potsdam (Erich Mendelsohn 1917–1921).

I had intended this walk to lead from one bookshop – Envie de Lire in Ivry – to another, and this other is here at the heart of this quarter, on the Place du Caquet. Folie d’Encre is both the opposite of and the equivalent to Envie de Lire. It is larger, lighter, more orderly, with no unstable piles or outside bins, but it is for Saint-Denis what Envie de Lire is for Ivry: a centre, a meeting point, a place of political animation. The owner, a woman whom we shall call S. and whose children come from East and West Africa, has been able to establish ties with the neighbouring cinema, the Gérard-Philipe theatre and even with the basilica, where she organizes lectures. Children come and do their homework among the books, voluntary organizations hold their meetings here, and the local people speak of ‘their’ bookshop. Gatherings for which mothers prepare African dishes take place not to discuss successful titles but rather questions facing a population who are in great majority Arab or black. ‘Public hearings’ are envisaged, which will not be debates where boredom is on the agenda.

The mairie, still communist today, supported the establishment of this bookshop in the town centre. On the Place Jean-Jaurès, its ‘Third Republic’ architecture sits next to the façade of the neighbouring basilica without too much discomfort. Nothing recalls the serious events that took place here between the wars, which is understandable since such disagreeable memories cannot help anyone. Yet it was Saint-Denis, and particularly its mairie, that saw the spectacular rise of Jacques Doriot: an engineering worker demobbed in 1918, leader of the Young Communists after the Tours congress, at the front of anti-militarist and anti-colonial struggle against the war in the Rif, deputy for Saint-Denis at the age of twenty-five when he came out of prison, and, as mayor of the town when he was thirty, the most popular member of the PCF leadership. But his opposition to the ‘class against class’ line would lead him first to a break with Thorez, followed by a drift into fascism that culminated in his alignment with the Nazis under the Occupation. A terrible story, of which I imagine many present-day inhabitants know nothing.

The Place Jean-Jaurès is the start of the Rue de la République, the town centre’s pedestrian axis. It is reminiscent of the Rue du Faubourg-du-Temple, yet still more diverse if that is possible – veils, turbans, braids and dreadlocks, baseball caps, beanies – a whole world of young people, amid poor shops selling clothes and perfume, or unlocking mobile phones. The pace is slow and the ambience peaceful, as in an Oriental town. The most penetrating eye would not detect any symptom of embryonic gentrification, yet this is the very opposite of a ghetto, rather a different form of life that has taken root in this street bordered by working-class flats from the nineteenth century, where I feel as much at home as if I had always lived here.

It ends opposite a rather ugly church built by Viollet-le-Duc. Strange that this restorer of so many magnificent monuments – including the basilica at the other end of the street – should have been the author of such mediocre architecture when he turned to original work. Going round the church on the left, following the line of the RER and Transilien railways in a desolate landscape, you end up where the Canal Saint-Denis joins the Seine. A worn-out lawn and a few poplar trees mark the confluence. Let us hope this will remain as simple, and not undergo the fate of another meeting of waters, that of the Marne and the Seine spoiled by an ill-sited hotel in the form of a pagoda.

To return to Paris I walk through a landscape of shacks, recent buildings and construction sites until I reach the Saint-Denis station. Before arriving there, I learn from a hoarding, written in the style particular to this kind of announcement, that ‘a new eco-quarter, a new way of living, an industrial heritage upgraded by the presence of artists, a quarter at the gates of Paris, connected, accessible and alive’ is to be built here. In the overcrowded station, dirty and uncomfortable, you have to be careful not to upset the brutes of the Sécurité Ferroviaire and find yourself up against the wall, hands in the air, and intimately searched. The spectacle is permanent. Such are the two faces of Saint-Denis, one radiant, the other sordid and brutal, between the Californian ‘Marlowe’ of Raymond Chandler and the African ‘Marlow’ of Joseph Conrad.

Images of Paris have always been multiple and contrasting, from Baudelaire’s ‘Paris sombre’ to the Hollywood dream of An American in Paris. And yet, at certain disturbing moments, when the city ceased to be ‘a festival’, a particular picture is constructed whose features are strangely similar in different epochs: a city threatened by the influx of foreign elements, by invasion – Paris was often taken as a metonym for France. Under the Second Empire, the guests of Princesse Mathilde – Taine, Flaubert, the Goncourt brothers – feared the Paris populace and were relieved by the crushing of the Commune, which according to Maxime du Camp was composed three-quarters of foreigners. Seventy years later, under the Occupation, Céline, Brasillach and Rebatet denounced (sometimes in the literal sense) the Jews omnipresent in Paris, claiming that ‘it took the insane dogma of equality between men for them to parade among us once more’.4 Today, another seventy years on, ever more successful authors speak of ‘Islamists’ in the banlieues – especially in Paris – in the same way as Maurras treated the Jews and Dumas fils treated the rebellious workers. The same mixture of contempt and fear appears in their discourse, always with a police component, a more or less explicit appeal for a muscular response to those who trample on our precious ‘values’.

I am confident that Paris will shake itself up and get rid of this miasma once again. I would be tempted to follow the illustrious example of Stendhal, who wanted the words on his tomb to read: ‘Arrigo Beyle, Milanese’, since ‘Parisian’ is indeed what I feel myself to be, far more than French or Jewish – garments that do not suit me at all.

Having always lived in this great city of ten million human beings, I understand and am even sorry for those who live in the ghettos of the rich, and are scared when they emerge and see so many people who do not look like them. They reassure themselves by thinking that all will be well so long as they themselves, their newspapers and their TV channels, ensure the ever-lasting resignation of the Parisian people, of cashiers and waiters, bus drivers and building workers, unemployed, delivery drivers and illegal immigrants – this proletariat who people the streets I have crossed in this short walk across a much wider city. I think they are mistaken. I think that, with new music and words, this multi-coloured proletariat bears the inheritance of the memorable journées whose traces I have shown. Despite its disorganization, and its lack of clear awareness of this inheritance, it is united by the sense of its endless exploitation, and will show one day that the people have not lost the battle of Paris.