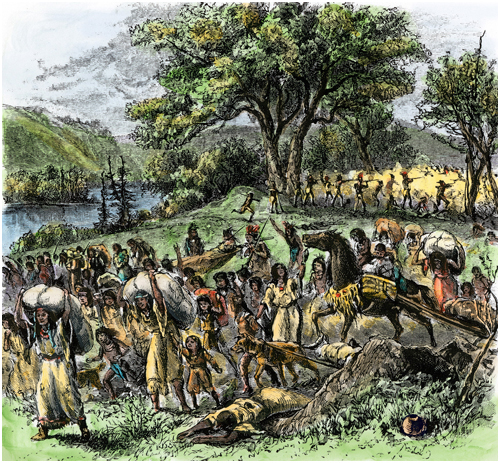

Western Removals, 1800–1840

Iroquois Influence on the U.S. Constitution, 1789

Rhianna C. Rogers and Menoukha R. Case

Chronology

1142 |

August 31. Iroquois Confederacy’s body of law is adopted. |

|

1490s |

Columbus brings back reports of egalitarian indigenous cultures. |

|

1500s |

Montaigne and other writers cite sixteenth-century Iroquois visitors to Europe as pointing out injustices of class inequality, something Europeans had taken as natural. |

|

1754 |

The 1754 Albany Congress, or “The Conference of Albany,” held between June 19 and July 11, 1754, illustrates Haudenosaunee/Iroquois influence on colonial U.S. government. |

|

1775 |

When the 1775 Continental Congress debates independence, Haudenosaunee/Iroquois chiefs are formally invited. |

|

1787 |

John Rutledge, a Constitutional Convention member and the drafting committee chair, uses the Iroquois Confederacy’s structure to argue that political power works best with joint rule. |

|

1788 |

June 21. New Hampshire becomes the last necessary state to ratify the U.S. Constitution. |

|

1988 |

October. The Haudenosaunee contribution is officially recognized as the 100th U.S. Congress passes a resolution that acknowledges “the historical debt which this Republic of the United States of America owes to the Iroquois Confederacy and other Indian Nations for their demonstration of enlightened, democratic principles of government and their example of a free association of independent Indian Nations” (H.R. Res. 311, 100th Cong. 1988). |

European thinking has had a major impact on mainstream American understanding of Native Peoples in general, and United States and Native history in particular. Therefore, understanding of Iroquoian influences on the United States government is extremely limited. Yet, the Haudenosaunees, the Native name for the Iroquois, played a profound historical role in European liberation from monarchy, culminating in creation of the U.S. Constitution and its associated governmental systems. Their influence has continued to shape American history.

Although the U.S. Congress acknowledged the influence of the Haudenosaunee Constitution on the U.S. Constitution in 1988, for the better part of U.S. history very few outside of Indian country, academia, and the federal government were aware of the Haudenosaunees’ influence on the development of American governmental systems. In fact, much foundational work in the field of American government has, consciously or unconsciously, excluded references to Haudenosaunee contributions (Payne 1996, 605–06). Noted scholars and respected Native American leaders have argued for the revision of current historical narratives to include a broader spectrum of non-European influences on the development of the U.S. government (Deloria, ed. 1992, 1–12). Despite ongoing conversations, this knowledge still remains obscured from public consciousness. Seneca scholar John Mohawk suggests people seek clues as to why this is still the case within the development of Euro-American worldviews expressed in histories, media, and ideologies of the American Indian:

Historians have been powerfully influenced by the ideas and attitudes the West has constructed to explain who the Indian was/is in relation to the European. Most of the history has been created to tell a story, not of the Indian, but of the European … There has been a strong tendency among historians to examine the record and, where the evidence is inconsistent with the story they wish to tell, to construct motives, to omit inconvenient facts, and to draw conclusions based more on their constructions than on the available evidence. (quoted in Deloria, ed. 1992, 44, 47)

Due to Western history’s reliance on written words, oral histories long remained outliers within mainstream historical discourse, but awareness of them is growing. J. Frederick Fausz notes in his article “Patterns of Anglo-Indian aggression and accommodation along the mid-Atlantic coast, 1584–1634”: “Since 1975 a virtual revolution in scholarship has transformed and informed the interpretation of Anglo-Indian relations in colonial North America … The historian’s unflagging fascination with the origins and evolution of English colonial institutions and societies produced two mature ‘schools,’ or broad overviews, for interpreting the period. But while both the England-focused Frontier school increased our knowledge of Whites in the colonial era, each approach ignored or distorted the considerable contributions of Native Americans who had strongly influenced London policy-makers and New World frontiersmen alike over the centuries” (quoted in Deloria, ed.1992, 62). Such gaps and distortions can be addressed through studying the period and process through Haudenosaunee eyes. Therefore, several sections below contain oral histories; please refer to them as you read.

Through Their Own Eyes: The Haudenosaunee/ Iroquois Confederacy

By the time Europeans made contact with the Haudenosaunee/Iroquois, their Confederacy was a long established, sophisticated political and social system that united the territories of six nations in a symbolic longhouse that stretched across what is now the state of New York.

From its inception, political activity within the Confederacy reflected a true democracy of multiple local councils with assigned representatives to the Confederacy’s council. However, proceedings and the policies at which the Confederacy arrived were recorded in non-Western ways. Unlike Western political documents, Haudenosaunee/Iroquois political narratives are rich with folktales, origin stories, legends, and rituals. Many of the Confederacy’s foundational narratives were recorded in wampum and conveyed orally from person to person as a way to encourage camaraderie, teach morals, impart wisdom and respect, and promote proper societal behaviors.

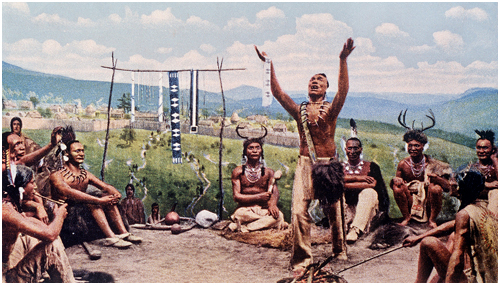

In 1988, the United States passed a resolution to recognize the influence of the Iroquois on the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights. This scene depicts Hiawatha speaking during the founding of the “League of Iroquois tribes” or “Confederation of Five Nations” c. 1570. (Fototeca Gilardi/Getty Images)

The Haudenosaunee people’s principal governing authority is the Grand Council of Chiefs appointed by the Clan Mothers, which operates under the tenets of the Great Law of Peace. Each nation has its own representative governments to govern daily activities; the Grand Council oversees issues that apply to the Confederacy as a whole. The Grand Council is composed of members of the Six Nations. As Bruce Johansen states, “[The Grand Council’s] decision-making process somewhat resemble[s] that of a two-house congress in one body, with the ‘older brothers’ and ‘younger brothers’ each comprising a side of the house. [The Onondaga occupy] an executive role, with a veto that could be overridden by the older and younger brothers in concert” (1982, 23). In essence, each tribe retains autonomy to deal with its internal affairs; simultaneously, the Grand Council deals with the problems that may affect all the nations within the Confederacy, meeting to discuss matters of common concern, such as war, peace, and making treaties. Though the Grand Council cannot interfere with each tribe’s internal affairs, unity for mutual defense, represented by a bundle of five arrows tied together, is central to the unbroken strength that such unity implies.

Sidebar 1: Wampum and Oral History

Wampum belts are composed of long cylindrical beads made from quahog clamshell (purple) and Atlantic whelk (white). The Europeans called this wampum, from wampumpeag, an Alogonquin word. Kanatiyosh (1991) explains that the Iroquois used them as memory aids. For example, if a problem arose, a tribe would introduce it to the Confederacy for consideration. The Council would reach a decision and report to the Onondaga Council leader; if he agreed, the decision became unanimous and would be recorded in a wampum belt.

The Hiawatha Belt, consisting of four squares with a tree in the middle, represents the unity of the original Five Nations. The first square represents the Mohawk Nation; the second the Oneida Nation; the central heart or the tree represents the Onondaga Nation; the square left of the tree represents the Cayuga Nation; and the last square represents the Seneca Nation. White lines leading away from the Seneca and Mohawk Nations represent paths welcoming new tribes who agree to follow the Great Law of Peace.

Each of the Nations has a special role, with responsibilities particular to their situations. As Barbara Barnes (1984) recounts in Tuscarora oral history:

The “Twenty-Second Wampum” illustrates that after all of the Chiefs have debated, there is one Onondaga Chief, Hononwiretonh, whose duty it is to sit and listen to all of the debate; the matter is then turned over to him for final approval, if all are in consensus. If he refuses to sanction the solution, then no other chief has the authority to pass the legislation. Hononwiretonh is not allowed to refuse sanctioning the matter unless there is a strong basis for his refusal. As can be seen, the Great Law provides for numerous checks and balances of power and depends on consensus of all fifty chiefs for its decision making. (quoted in Kanatiyosh 1991)

The Haudenosaunee/Iroquois Confederacy is a direct reflection of the integration of oral traditions, morals, culture, and religion in government. Unlike European systems of government, which attempt to make a distinction between laws and culture, the Haudenosaunee system encompasses a holistic approach to life and society. (See “The Haudenosaunee Confederacy: Natural Law, Clan Mothers & Elders” in Sidebar 2.) As the Haudenosaunees describe it, “What makes [the Confederacy] stand out as unique to other systems around the world is its blending of law and values” (Haudenosaunee Confederacy 2014c).

Settlers and Indians: Crafting a Nation

As described in the Chronology, democracy was not an entirely new idea to the colonists, since shocked and amazed stories about egalitarian Native cultures had been drifting across the ocean to Europe since Columbus’s time. As the British settled into the hills of New England and the southern east coast, actions such as convening the Albany Congress indicated their respect for Haudenosaunee agency and power (see “Colonial Era Haudenosaunee Figures” in Biographies of Notable Figures):

The founding fathers of the United States had ample opportunity to study and learn from the Haudenosaunee. During the 1730s and 1740s English allegiance with the Haudenosaunee was essential if the English hoped to prevent the French from encroaching on the territory. During this time colonists intermingled with the Haudenosaunee in an attempt to build trust and establish treaties that would ensure their alliance. (Haudenosaunee Confederacy 2014c)

Sidebar 2: The Haudenosaunee Confederacy: Natural Law, Clan Mothers & Elders

For the Haudenosaunee/Iroquois, “law, society and nature are equal partners and each plays an important role” (Haudenosaunee Confederacy 2014a). Since they are intertwined, concepts about nature affect political decisions, wisdom, faith keeping, and customs. Thus, governance is based on the principle of mutual reciprocity, a respect and alignment between human law and natural law expressed in all decisions and behaviors. As such, each individual plays a unique role in the ultimate fulfillment of collective spiritual and political goals. This moral integration is exemplified through religious ceremonies enumerated under the Haudenosaunee Constitution’s Articles 99–104, which state, “freedom of religion is also simultaneously protected by allowing each Nation to keep its own rituals” (Ibid.). This clause is a strong indication of spirituality’s integral nature in Haudenosaunee life and politics.

The Great Law proposes that all life is interconnected spiritually, environmentally, and communally. In essence, the system cannot work well if all aspects are not kept in balance autonomously, and that includes resource and gender balance. Haudenosaunee administration relies heavily on women in matrilineal political positions, known as Clan Mothers, who appoint male delegates to speak for each clan. The Great Law bans bloodshed and ensures peace as a way of life. Peace is reliant on equity, and the Clan Mothers are also responsible for the equitable distribution of corn.

The original Five Nations were divided into elders (Mohawk, Onondaga, and Seneca) and youngers (Oneida and Cayuga). Despite the deference owed to elders, all Council decisions had to be unanimous. A sixth tribe, the Tuscaroras, migrated to the area in approximately 1714. They are known as Iroquois (externally) and Haudenosaunees (internally). Today, the Six tribal nations of the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee Confederacy is still a matriarchy, still defends natural law, and still holds Council.

The settlers also turned to the Haudenosaunees to find inspiration for the American Revolution, using Native Americans as their model for freedom. (See “Colonial American Figures” in Biographies of Notable Figures.) As exemplified by their dressing as Mohawks during the Boston Tea Party, the colonists “adopted the Indian as their symbol … Popular engravings showed colonists—portrayed as Indians—being oppressed by British … [They declared they] could live without England, surviving on ‘Indian corn’ ” (Hurst Thomas 2000, xxvii, 11–3, 199). The Haudenosaunee/Iroquois Confederacy’s influence on the United States goes beyond inspiration to key aspects of governance. As the Chronology describes, it is well documented that the Haudenosaunee Great Law served as a blueprint for the U.S. democracy, the Constitution, and American governmental structure (Johansen 1982; Payne 1996).

The 1789 U.S. Constitution arose from a long process of intercultural exchange marked by tenets that were at odds from the outset. American exposure to indigenous peoples began through quests for wealth, power, and cultural expansionism. The indigenous peoples’ impressively egalitarian lifestyle captured European imagination and initiated thirst for broader powers than monarchy and feudalism permitted. Still, American settlers resisted true egalitarianism, which would have required them to eschew the patriarchy and racialism that allowed them to accumulate the wealth for which they had ventured forth. To negotiate the quandary of how to gain power without giving it away to everyone, and having no other model of broader governance, they adapted a Haudenosaunee/Iroquois governmental structure designed for inclusiveness. Drafting and re-drafting the Constitution to accommodate vested interests culminated in a paradoxical document that, on the one hand, limited privilege to select groups and, on the other hand, carried egalitarian sensibilities that would lay the groundwork for the U.S. Constitution.

Ratification Struggles: Shifting Identity

There are key similarities between Haudenosaunee and U.S. governance structures. Parts of the U.S. Constitution contain word-for-word replication of concepts from the Great Law (Kanatiyosh 1991). Along with the very idea of freedom, the United States adopted the retention of rights by member units (Six Nations or U.S. states) and a tripartite separation of powers. For example, the Clan Mothers form a Council of Matrons, an executive branch that assigns many other roles and determines general policy. Village, tribal, and confederacy councils are legislative branches, implementing those general policies. A joint matrons’ council and men’s council oversees the judicial branch of governance. As the Haudenosaunees note, there are a variety of similarities between these documents:

Both models stress the importance of unity and peace and provide freedom to seek out one’s success. Similarities can also be seen in the symbols of each nation. While the Great Law features five arrows bound together as a symbol signifying the unity and strength of the five nations, the seal of the United States uses an eagle clutching a bundle of thirteen arrows signifying the thirteen original colonies.

The way the US Congress operates is also similar to the actions made by the Grand Council as outlined by the Peacemaker. Within [the] Grand Council meet the Chiefs of each nation which then divide into sections of Elder Brothers and Younger Brothers. This model is very similar to the US Constitution’s two-house congress. (Haudenosaunee Confederacy 2014c)

There are also clear differences between the Haudenosaunee and U.S. Constitutions. Three main differences are: (1) while both provide for freedom of religion, the Haudenosaunee constitution remains spirit-based, and the U.S. Constitution separates the spiritual from the secular; (2) the Haudenosaunee constitution is matriarchal, while the U.S. Constitution is patriarchal; and (3) assignment of roles by the Council of Matrons follows clan lines and, therefore, matrilineal bloodlines. The Haudenosaunee constitution states that “the body of our mother, the woman, [is] of great worth and honor … [S]he shall have the care of all that is planted by which life is sustained and supported and the power to breathe is fortified: and moreover that the warriors shall be her assistants” (Gunn Allen 1986); whereas the original U.S. Constitution followed patrilineal lines of power and only extended the right to govern to men. Interestingly enough, the Matron’s Council has economic power equivalent to redistributing taxes for sustaining the populace, and also carries responsibility similar to that of the U.S. role of commander in chief. Some could say, therefore, that the Iroquois Confederacy influenced not only the U.S. Constitution, but also early feminist movements to counter that constitution’s patriarchal nature (Gunn Allen 1992).

The ratification debate in which these differences were wrangled, and the document containing its outcome, known as the U.S. Constitution, register critical differences between European and Native worldviews. Perhaps it comes down to motivation. Seventeenth-century Puritan narratives about religious freedom notwithstanding, the majority of Europeans came to Turtle Island for opportunity rather than equality; they wanted to ameliorate the feudal system, to displace bloodline birthright with a broader category of “earned” wealth. But this wealth was established at the expense of unpaid labor (that of women and slaves) and land “redeemed” from the very “savages” whose constitutional model allowed the colonists to unite and fight England. The very idea of the kind of equality enjoyed by Native Americans had been unknown to them; they found it exhilarating and inspiring, but only partially adopted it. Thomas Jefferson, one of the “Founding Fathers” of the US, illustrates this:

Jefferson believed that freedom to exercise restraint on their leaders, and an egalitarian distribution of property secured for Indians in general a greater degree of happiness than that to be found among the superintended sheep at the bottom of European class structures. Jefferson thought enough of happiness to make its pursuit a natural right, along with life and liberty. In so doing, he dropped “property,” the third member of the natural rights trilogy generally used by followers of John Locke …

… To place “property” in the same trilogy with life and liberty … would have been a contradiction.… Jefferson composed some of his most trenchant rhetoric in opposition to the erection of a European-like aristocracy on American soil.… [He] often characterized Europe as a place from which to escape—a corrupt place, where wolves consumed sheep regularly, and any uncalled for bleating by the sheep was answered with a firm blow to the head. (Johansen 1982, 103)

Nevertheless, Jefferson built his Virginia estate on Cherokee land and acquired wealth through slavery. He was also known by some as one of “The Fathers of American Archaeology,” a reputation gained in part by measuring African and Native Americans’ skulls to prove Haudenosaunee inferiority. It is not surprising, therefore, that the U.S. Constitution holds an African to be three-fifths of a person and that the Declaration of Independence refers to “merciless Indian savages.”

Before the American Revolution, the term “American” referred only to indigenous peoples; afterwards, the settlers adopted it to express their own identity. The appropriation of “Indianness” in colonial times, therefore, is both hidden in and central to U.S. democracy. Its final expression in the Constitution is a fascinating register of what “Indianness” the colonists accepted and rejected, and why. As Gunn Allen states, “American colonial ideas of self-government came as much from the colonists’ observations of tribal governments as from their Protestant or Greco-Roman heritage. Neither … had the kind of pluralistic democracy that has been understood in the United States since Andrew Jackson, but the tribes, particularly the gynarchical tribal confederacies, did” (1992, 218). Greco-Roman tradition was carried on in oligarchic values, such as restriction of citizenship to white property-owning males over 21years old, and English patriarchal feudalism lingered both through those citizenship parameters and the retention of slavery. One of the most notable changes that the European-Americans made, as Gunn-Allen (1982) indicates, was to reject bloodline aristocracy and monarchy; Gunn purports that all other changes were adopted from Native Americans.

The Arc of U.S. History and Contemporary Questions

In sum, while the Haudenosaunees have encouraged a voice for everyone, the U.S. Constitution originally restricted representation. The seed of egalitarianism, however, has borne fruit. Phrases, words, and the very spirit of liberty embedded in the U.S. Constitution’s rhetoric have become effective tools in a continual quest for equality in America. Highlights from the history of suffrage offer an example:

Faithkeeper Oren Lyons, Chief of the Onondaga Nation, has called the Haudenosaunee influence on the U.S. Constitution “an ember … from [Haudenosaunee] fire.” That ember ignited both suffrage and all kinds of struggles for rights. Still, the original rift is registered in ongoing debates about what, exactly, the American ethos is. What is the American concept of liberty and justice? Is individual liberty paramount, no matter the cost to lands, waters, and society? Just how should Americans apply the concept of “justice” to contemporary issues, from ecological degradation to human rights? For what purpose did Americans unite, and to what ends should U.S. collective taxes be distributed? Should Americans practice the values of equity and reciprocity, caring for all members of society, like the Haudenosaunee Matron Council does in distributing corn? Oren Lyons continues:

So we are now facing another situation. Can we get … this great light to come again? And that’s up to this generation … we’re elders, you and I now. I mean, we can say from our older position, “It looks like a lost cause.” But if you were to speak to the young man, the young person, the young woman, she’d say, “No. This is my life. I shall survive. You can’t tell me that it’s lost. That’s my determination.” She will say, and he will say that, and they are saying it.

So we can say, “Well, it looks bad from here.” And from there they say, “Well, it looks tough, but it isn’t lost.” And that’s the law that they were talking about from Gunyundiyo, when he said, “Don’t let it be your generation.” And the law prevails, what we call the Great Law, the common law, the natural law. (Lyons 1991)

Lyons’s words are reminders of another one of those tenets at odds from the outset: Indigenous constitutions accord rights to nature, while Western constitutions accord “natural rights” to human beings. Indigenous concepts of mutual reciprocity and natural law become ever more relevant as people face the ecological crisis that has developed under the dominance of Western law. Some might suggest that this is the time, when the ember is still lit, to broaden recognition of Native influences and look to indigenous peoples for insights moving forward.

Biographies

Pre-Contact Haudenosaunee Figures

Early Haudenosaunee figures must be addressed collectively to reflect the cultural norms of that time. The stories of Peacemaker, Hiawatha, Tadodaho, and Jigonsaseh are intertwined. That said, two of the Haudenosaunee/Iroquois oral tradition’s most notable figures are the Great Peacemaker (also known as Deganawida or Dekanawida) and the visionary Hiawatha. There is great debate about both men’s origins and their affiliated status within the Six Nations; however, it is universally believed, among Natives and non-Natives alike, that their interactions formed the foundations of the Great Law seen within the Six Nations today. Peacemaker is credited with spreading peace and unity through the Haudenosaunee peoples. He did so by introducing the Great Law of Peace, or Gayanesshagowa, and its three central principles (i.e., righteousness, justice, and health) across the five original nations (National Museum of the American Indian-Education Office 2009, 4). Hiawatha, who may have been either a pupil or contemporary of the Great Peacemaker, continued the unification of tribes and ultimately established the foundations for what would become the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Haudenosaunee traditions describe Hiawatha as residing with either the Onondagas or the Mohawks after having descended from his dwelling in the skies. The Haudenosaunees believe that Hiawatha taught their ancestors the principles that the Great Peacemaker brought with him. Both men helped establish the Confederacy’s core values: the art of good living; the value and strength of mutual friendship and goodwill; the end of cannibalism; the advantages of sedentary living; and the mutual cultivation of the environment.

Either during or shortly after Hiawatha and Peacekeeper’s mission of peace, the people of the Confederacy selected their first leader. They chose Tadodaho, a chief of the Onondagas, for his power, valor, and control over his people. His title, Grand Sachem of the League, was conferred upon him by a delegation of the Mohawks who, as tradition indicates, found him seated in a dark swamp with snakes in his hair, smoking his pipe among drinking vessels made of his enemies’ skulls. Tradition states that after the Mohawks announced their mission, they offered Tadodaho the position; it is said that Tadodaho arose and accepted the office, and some versions indicated that Hiawatha and/or Peacekeeper combed the snakes out of his hair, making him more compassionate and less evil toward others. This act transformed Tadodaho into a compassionate leader, which affirmed the Onondagas’ place as the “firekeepers” of the new Confederacy (Grinde Jr. & Johansen 2001, 89).

Additionally, Jigonsaseh (known as Peace Queen and Mother of Nations, among other titles), who is said to have been a contemporary of Hiawatha and Peacemaker, was also instrumental in the pacifying of Tadodaho. She helped to cofound the Peace Confederacy, unite the Nations, and establish a strong female role within the Haudenosaunee political system (Johansen & Mann 2000, 176–77).

Colonial-Era Haudenosaunee Figures

In 1744, envoys from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia met in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, with delegates, or sachems, from the Six Nations. During their discussions, the Iroquois leader Canassatego advocated the American colonies’ federal union, exhorting the colonists: “Our wise forefathers established a union and amity between the [original] Five Nations. This has made us formidable. This has given us great weight and authority with our neighboring Nations. We are a powerful Confederacy and by your observing the same methods our wise forefathers have taken you will acquire much strength and power; therefore, whatever befalls you, do not fall out with one another” (Ibid). One Haudenosaunee account states, “Canassatego, the then Chief of the Onondaga, impress[ed] upon the colonists the importance of [the settlers also] forming a union of all the colonies. Canassatego expressed the difficulty [the Nations] had faced in dealing with each separate colony and how forming one union could repair the problem. The Haudenosaunee did not want to cement a union [with the settlers] until the colonies were united” (Haudenosaunee Confederacy 2014c).

Colonial British-American Figures

Among the Founding Fathers, Franklin may best illustrate the influence the Haudenosaunee/Iroquois had on newly formed American mindset. As the Haudenosaunees tell it,

In 1744 Benjamin Franklin ran a successful printing company in Pennsylvania running newspapers, money, and legal documents. It was during this period he began to become immersed in the treaty councils which were brought to him by Conrad Weiser, a man who had gained the respect of the Haudenosaunee and had even been adopted into the Mohawk nation. The treaty council proceedings were of high interest in Europe making them a profitable venture for Franklin. (Haudenosaunee Confederacy, 2014c)

The colonists’ need for alliance with the Haudenosaunee to further their revolution thus initiated consideration of the very idea of uniting states. For this reason, “the colonists’ ideals were beginning to diverge from those of Europe and Franklin began to look at a new system of government” (Ibid.).

Franklin also became the historian of this process:

Franklin, who owned a thriving printing business in Philadelphia, started printing small books containing proceedings of Indian treaty councils in 1736 … the books, the first distinctive forms of indigenous American literature, sold quite well, and he continued publishing such accounts until 1762. [Based on his interests in Native teachings,] in 1754, Franklin carried the Iroquois concept of unity to the critical Albany Congress, where he presented his plan of union loosely patterned after the Iroquois Confederation. An aging Mohawk sachem called Hendrick had received a special invitation from the acting governor of New York, James DeLancey, to attend the Albany Congress and provide information on the Iroquois government’s structure. After Hendrick spoke at the Albany Congress, DeLancey responded, “I hope that by this present Union, we shall grow up to a great height and be as powerful and famous as you were of old.” (Feathers & Feathers, 2007)

During the debates over the plan for the newly formed union, Franklin noted the Iroquois Confederacy’s strength and stressed the fact that the Nations maintained internal sovereignty, managing their own affairs quite effectively, without interference from the Grand Council. The Haudenosaunees supported this narrative, stating:

Following the Albany Congress Franklin drew up a plan that had all the British American colonies federated under a single legislature with a president-general who would be appointed by the Crown, a very similar model to the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Like the confederacy all states had to agree on a course of action before it could be implemented. Unfortunately at the time the colonies were not ready to unite and the crown disapproved of the freedom it provided and the plan failed. (Haudenosaunee Confederacy 2014c)

The Albany Congress–1794, a mural located in the U.S. Capitol building, depicts some of the meeting’s delegates (from left to right, excluding the blacksmith and farmer): William Franklin and his father Benjamin (Pennsylvania); Governor Thomas Hutchinson (Massachusetts); Governor William Delancey (New York); Sir William Johnson (Massachusetts); and Colonel Benjamin Tasker (Maryland). The blacksmith, on the left, symbolizes the importance of ironworking in the mid-eighteenth century, and the farmer with his scythe, on the right, represents the growth of agriculture in the colonies. Significantly, there are no Natives portrayed in this painting, though Franklin discussed them in his writing. Some might argue that this omission further perpetuates the dismissal of Native contributions to the formation of the United States and its Constitution.

DOCUMENT EXCERPTS

Oral History of Hiawatha’s Speech

You (Mohawks) who are sitting under the shadow of The Great Tree whose roots sink deep into the earth, and whose branches spread wide around, shall be the First Nation, nearest the rising of the sun, because you are warlike and mighty. You (Oneidas) who recline your bodies against The Everlasting Stone, emblem of wisdom, that cannot be moved, shall be the second nation, because you always give wise counsel. You (Onondagas) who have your habitation at the foot of The Great Hills, and are overshadowed by their crags, shall be the third nation, because you are all greatly gifted in speech. You (Cayugas) the people who live in The Open Country, and possess much wisdom, shall be the fourth nation, because you understand better the art of raising corn and beans, and making houses. You (Senecas) whose dwelling is in The Dark Forest nearer the setting sun, and whose home is everywhere, shall be the fifth nation, because of your superior cunning in hunting. Unite, you five nations, and have one common interest, and no foe shall disturb or subdue you. You, the people, who are as the feeble bushes, and you, who are a fishing people (addressing some who had come from the Delawares, and from the sea-shore), may place yourselves under our protection, and we will defend you. And you of the South and West may do the same—we will protect. We earnestly desire the alliance and friendship of you all. Brothers, if we unite in this great bond, the Great Spirit will smile upon us, and we shall be free, prosperous, and happy. But if we remain as we are we shall be subject to his frown. We shall be enslaved, ruined, perhaps annihilated. We may perish under the war-storm, and our names be no longer remembered by good men, nor repeated in the dance and song. Brothers, these are the words of Hi-a-wat-ha. I have said it. I am done.

Tradition continues that Hiawatha then ascended into the heavens in a mysterious canoe and vanished. The five original Nations established the Confederacy the following day.

Source: Henry R. Schoolcraft. Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Volume 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1853, 317.

A Congressional Resolution Affirming Haudenosaunee Influence on the United States Constitution

In 1988, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution acknowledging that the ideas and principles expressed by the Iroquois Confederacy of Nations influenced the men who had developed the U.S. Constitution, nearly 200 years earlier.

Resolution, 311, 100th Congress, 1988

To acknowledge the contribution of the Iroquois Confederacy of Nations to the development of the United States Constitution and to reaffirm the continuing government-to-government relationship between Indian tribes and the United States established in the Constitution.

Whereas, the original framers of the constitution, including, most notably, George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, are known to have greatly admired the concepts of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy;

Whereas, the Confederation of the original Thirteen colonies into one republic was influenced by the political system developed by the Iroquois Confederacy as were many of the democratic principles which were incorporated into the Constitution itself . . Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the House of Representatives (the Senate concurring), That—

Source: H.R. Res. 311, 100th Cong. 1988.

Further Reading

Deloria, Vine, ed. Exiled in the Land of the Free. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 1992.

Feathers, Cynthia and Susan Feathers. “Franklin and the Iroquois Foundations of the Constitution.” The Pennsylvania Gazette, 2007. http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0107/gaz09.html

Feathers, Cynthia and Susan Feathers. Two Tracts: Information to Those Who Would Remove to America, and Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America. J. Stockdale, 1784. http://mith.umd.edu/eada/html/display.php?docs=franklin_bagatelle3.xml

Grindle Jr., Donald A. and Bruce E. Johansen. “Perceptions of America’s Native Democracies: The Societies Colonial Americans Observed,” in Native American Voices, 3rd ed. Edited by Susan Lobo, Steven Talbot, and Traci L. Morris.; 62–69, 2010. http://faculty.ithaca.edu/kbhansen/docs/namindians/grindejohansen.pdf

Gunn Allen, Paula. “Who Is Your Mother?: Red Roots of White Feminism,” 1986. http://spot.colorado.edu/~wehr/491R9.TXT

Haudenosaunee Confederacy. “About the Haudenosaunee Confederacy,” 2014a, internal links http://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/aboutus.html

Johansen, Bruce E. “Native American Political Systems and the Evolution of Democracy: An Annotated Bibliography.” The Six Nations: The Oldest Living Participatory Government on Earth, 1997. http://www.ratical.org/many_worlds/6Nations/NAPSnEoD.html

Johansen, Bruce E. Forgotten Founders: Benjamin Franklin, the Iroquois, and the Rationale for the American Revolution. Boston: Harvard Common Press, 1982. http://www.ratical.org/many_worlds/6Nations/FFchp2.html

Johansen, Bruce E. “Native American Ideas of Governance and U.S. Constitution,” 2009. http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/publication/2009/06/20090617110824wrybakcuh0.5986096.html#ixzz3Zv0CWsZQ

Johansen, Bruce Elliott, and Barbara Alice Mann, eds. Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000.

Kanatiyosh. “The Structure of the Great Law of Peace,” Me and U, Mother Earth and Us: A Haudenosaunee Perspective, 1999. http://tuscaroras.com/graydeer/influenc/page2.htm

Lyon, Oren. “Oren Lyons—The Faithkeeper: Interview with Bill Moyers.” In Bill Moyers, A World of Ideas, Public Affairs Television, July 3, 1991. Transcript. http://www.ratical.org/many_worlds/6Nations/OL070391.html

Murphy, Gerald. Haudenosaunee Constitution. Portland State University, 2001. http://www.iroquoisdemocracy.pdx.edu/html/greatlaw.html

Payne, Samuel B., Jr. “The Iroquois League, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution.” Special issue: “Indians and Others in Early America,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 53 (3]): 605–620, 1996. http://www2.hawaii.edu/~rrath/hist460/IroqInf-Payne.pdf

Wallace, Paul A.W. and Ka-Hon-Hes. White Roots of Peace: The Iroquois Book of Life. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 1994.

American Indian Health Services, 1802–1924

Alexis Kopkowski

Chronology

1802 |

Smallpox, a contagious disease, reaches epidemic levels for many American Indians. Originating in the central United States, it continued to spread along the Missouri River to the Pacific Northwest. It is estimated that as many as 80 percent of the total population of some tribes was lost to the disease. |

|

1802 |

Army physicians provide a limited number of smallpox vaccines to a small number of American Indians who are considered to be frontier Indians. These American Indians lived near Army forts where the physicians were located. |

|

1810 |

Smallpox spreads to the Great Lakes and northern plains. |

|

1819 |

An appropriation of $10,000 by Congress is made for American Indians living east of the Mississippi River to be taught “the habits and arts of civilization.” Missionaries also perform some very basic nursing and health care to American Indians. |

|

1820–1830 |

Through a series of U.S. Supreme Court cases known as the “Marshall Trilogy,” the United States’ trust relationship with American Indians is established and solidified legally. |

|

1832 |

Congress appropriates $12,000 to provide American Indians with smallpox vaccines. |

|

1831 |

In the latter part of the year, a smallpox outbreak greatly impacts the Pawnee tribes of the United States. |

|

1836 |

Health services and physicians are provided to both the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes by the federal government. |

|

1837–1838 |

The smallpox epidemic reaches its height as it continues to decimate the American Indian population, and it once again follows along the Missouri River. |

|

The Department of War is no longer the agency in charge on Indian Affairs. The department that would then oversee Indian matters is the Department of Interior. |

||

1880 |

An increase in government responsibility and American Indian health care occurs as the federal government then operates four hospitals that employ 77 physicians. The hospital’s sole purpose is to provide health care to American Indians. These hospitals almost exclusively serve American Indian boarding school students. Funding for the hospitals and physicians is made possible through education funds. It is then further emphasized that the health of American Indian students is important to educators and policymakers alike. |

|

1908 |

The Chief Medical Supervisor position is created and marks the beginning of professional medical supervision of American Indian health. |

|

1911 |

Congress appropriates $40,000, which is earmarked for American Indian health services through an appropriation act. The appropriation explicitly calls for “the relief of distress and prevention of diseases” for American Indians. |

|

1911 |

Three health outcomes that negatively impact American Indians are acknowledged. The contagious diseases trachoma and tuberculosis, as well as infant mortality, are all declared to be national health tragedies by the Indian Medical Service. |

|

1912 |

President William Howard Taft delivers a message to Congress, calling for more funding. He notes that the conditions for American Indians are “very unsatisfactory.” At the time, the death rate for American Indians is more double that of the general U.S. population. Taft also calls for an increase in the salary of physicians who are employed by the government to care for American Indians, as their salary is half of what the majority of government employees make at the time. |

|

1913 |

Dental services are added to the provision of American Indian health care. Five travelling dentists are employed to visit and deliver dental care to Indian boarding schools and American Indian reservations. |

|

1919 |

The House Committee on Indian Affairs recommends that the provision of Indian health care be taken out of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and transferred to the United States Public Health Service (USPHS). |

|

Congress passes the Snyder Act (42 Stat. 208) on November 2, 1921. This act continues federal authority over many American Indian services. It is one of the first times that the provision of health care to American Indians by the federal government is made explicit. The act calls for the “relief of distress and conservation of health of Indians.” It is the first authorization for the Indian Health Service (IHS). Adequate funding, healthcare staffing, and training are never achieved, and thus the health outcomes for American Indians during this time period remained poor. This leads to the health outcomes of American Indians to remain poor. |

||

1924 |

A medical division is established and housed in the Office of Indian Affairs. The new division becomes responsible for the administration of the growing number of federal programs and funds that are appropriated for improving and maintaining the health of American Indians. Overall, the health status of American Indians remains poor as epidemics continue to impact American Indian populations, and tribes look to the division to provide for health care in the form of medicines and physicians on their reservations. |

The Development of Health Care for American Indians and Alaskan Natives

The development, deployment, and administration of health care for federally recognized American Indians and Alaskan Natives underwent many different iterations during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is a common misconception held by the American public that American Indians and Alaska Natives enjoy “free” health care. Healthcare services and provisions provided for the American Indian and Alaskan Native populations by the federal government are essentially by contract fulfillment by the federal government. The provision of health care and services is both a moral and a legal obligation that the United States government must fulfill. Historically, the provision and organization of American Indian health care have been heavily influenced by the federal American Indian policy era of the time.

As found in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution (adopted in 1789), treaties, numerous court cases, executive orders, and legislation, the health care of American Indians and Alaskan Natives has been upheld as a responsibility of the United States government through the acknowledgement of a special government-to-government relationship between two sovereign nations (Rainie, Jorgensen, Cornell, and Arsenault 2015). In essence, the federal Indian Health Service (IHS) is America’s first prepaid health plan, paid by the cession of millions of acres of American Indian land. Many treaties explicitly stated that in exchange for land, services such as education and health care would be provided to the American Indians and Alaskan Natives by the federal government. It must be recognized that American Indians and Alaskan Natives—America’s original peoples—hold a unique position that has been shaped and influenced by their legal, social, and cultural standing. Large populations of American Indians and Alaskan Natives are entitled to services provided by the federal government. These services are available to members of federally recognized tribes, or sovereign Indian nations. Unfortunately, both historically and currently the provision of Indian health care has been largely missing from Congressional and political debate.

Sidebar 1: Timeline of Federal American Indian Policy Eras

1492–1600s: Doctrine of Discovery

The Pope issues a series of papal bulls (laws), which enforce the belief that the European, Christian explorers held dominion and power over any non-Christians and the land they occupied.

1600s–1871: Treaty-Making Era

This era pre-dates the United States and overlaps the reservation- and removal-policy eras because the U.S. government continued to make treaties with tribal nations throughout those eras. A treaty is an official agreement made between sovereigns. The United States can only enter into treaties with other nations. The U.S. Constitution declares that treaties, as well as the Constitution, are the “supreme law of the land.”

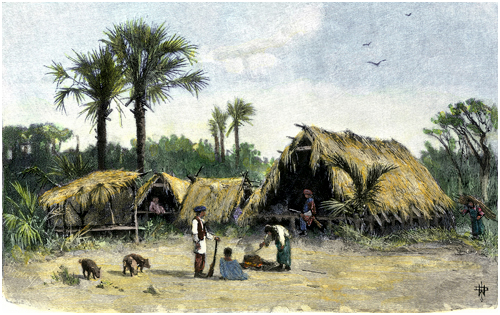

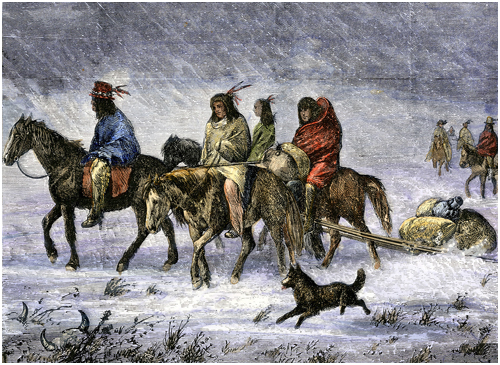

1830–1850: Indian-Removal Era

Congress is advised by President Andrew Jackson to remove American Indians who lived on the east coast and in the southeast and northeast of the United States and to relocate them to west of the Mississippi River to allow for the expansion of the United States. In turn, Congress passes the federal Indian Removal Act.

1850–1880s: Reservation Era

The reservation system is created to further relocate American Indians. It is deemed necessary when gold is discovered in many areas of the United States, and the non-American Indian population of the United States continues to increase rapidly.

1887–1930s: Allotment and Assimilation Era

Tribal land holdings are broken up as a way to assimilate American Indians. The goal is to decrease tribal sovereignty, “civilize” the American Indian population, and assimilate American Indians into the mainstream culture.

1930s–1945: Indian-Reorganization Era

Allotment was unsuccessful, and in response the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), a return to American Indian self-governance, is passed.

1945–1961: Termination and Relocation Era

The federal government begins to terminate the trust relationship it has with tribal nations. American Indians are also relocated to many urban areas, including San Francisco, California; Phoenix, Arizona; Chicago, Illinois; and St. Louis, Missouri.

1960s–Present: Indian Self-Determination Era

Following the civil rights era, the U.S. government officially begins to recognize the importance of sovereignty and self-determination. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act and the Indian Child Welfare Act are passed.

Originally, the federal government did not view the provision of health services to American Indians as part of the federal trust responsibility. The earliest episodes of healthcare delivery occurred when it was necessary to protect soldiers from nearby epidemics by inoculating American Indians who lived near the army bases. The Department of War was the first federal agency that was charged with American Indian health, beginning in the 1800s. At the time, this also reflected the nature of the relationship between the federal government and American Indians and Alaskan Natives, which was one of military confinement.

During the 1800s, many of the major health problems that plagued the United States were contagious diseases. Historically, the government was involved minimally in health care. However, as the connection between sanitation and the spread of disease became clearer, the government took on a larger role and interest in the overall prevention of the spread of disease. Following this trend, greater attention was also paid to American Indians and health during this time. As contagious diseases impacted American Indian populations who were living near army posts, army physicians began to administer vaccines (smallpox for the majority) in the hopes of containing the diseases. At this time, limited health care was provided sporadically as a stopgap emergency, and the idea of continued health care and/or prevention was not a policy or a stance that the government was taking.

In 1824, the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), housed within the Department of War, distributed to American Indian populations the funds received from Congress that were to be used for basic health care and vaccine provisions. The contagious disease smallpox continued to ravage American Indian communities. As the population continued to be impacted in great numbers, Congress finally provided funding for vaccines to be administered in larger quantities. In 1832, the goal of the funding was to “provide the means of extending the benefits of vaccination, as a preventative of smallpox, to the Indian tribes” (Rife and Dellapenna 2009, 2). This appropriation was named the Indian Vaccination Act, and the Secretary of War at the time, William Cass, oversaw the program in its entirety. This congressional funding marked the first time that Congress mandated direct healthcare services be provided to American Indian populations. While these vaccines no doubt made an impact in stopping the spread of the newly introduced, highly contagious disease, it did not end the epidemic, and the American Indian population continued to suffer. “No disease which has been introduced among the tribes, has exercised so fatal an influence upon them as smallpox” (Jones and Jones 2009, 76).

What might appear on the surface to be an altruistic act of the federal government was actually a way for the government to promote and leverage President Jackson’s Indian-removal program. This program called for the removal of tribes from east of the Mississippi River to west of the river. One way in which tribes who resisted moving would be forced to do so was through the withholding of these vaccines (Rife and Dellapenna 2009). It was in 1832 as well that federal treaty obligations for the provision of American Indian health care were first honored. During that year, the federal government promised health care to a small band of Winnebago Indians as contract fulfillment of their ceded land rights. At the end of 1841, contract physicians as well as the U.S. Army had vaccinated somewhere between 38,000 and 55,000 American Indians (Rife and Dellapenna 2009). These numbers, however, only represent a small percentage of the overall American Indian population of the time.

In 1849, the Department of the Interior was created to oversee the nation’s resources. As a result, the health care for American Indians and Alaskan Natives was transferred along with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) from the Department of War to the Department of the Interior. This transfer also coincided with the end of military control over American Indians and Alaskan Natives within the organizational entity of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (Bergman et al. 1999). American Indians were being moved to reservations during this time, often against their will. Moving to the reservation meant that many American Indians then had an increased risk of disease, due to the poor living conditions present on the reservations. The OIA was ill-equipped to manage the health care of reservation-dwelling American Indians, and this did not change during the OIA’s tenure in administering American Indian health care.

During the 1850s, health care, mainly in the form of vaccines, was also provided to a small population of American Indians located in the territories of Washington and Oregon because it was a part of their treaties with the federal government. The acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs was Charles E. Mix in 1858. His job involved responding to the myriad of requests from army officers and Indian agents who requested services at military outposts. OIA contract physicians who were given instruction on-site were charged with vaccinating American Indians as well as treating any American Indians who may have been ill at the time, free of charge.

In 1881, George Bushnell, who was placed in charge of Sioux (Lakota) prisoners of war, noted that the tribal members who were not confined to permanent dwellings were less prone to disease epidemics and illnesses than those who were (Dejong 2010). This introduction of “civilized” housing also led to a tuberculosis epidemic in the Red Lake Chippewa tribe. Traditionally, the Chippewas lived in clean housing and moved frequently. However, with the implementation of federal policy, they were moved to small and dark log houses with poor ventilation and light, which led to the stagnation of the air. These houses became breeding grounds for many contagious diseases (Dejong 2010). In 1910, Congress appropriated funds to create a tuberculosis sanitarium to help the Red Lake tribe, while a similar tuberculosis epidemic also occurred on the Rosebud Reservation of South Dakota at the same time.

The OIA’s policies regarding healthcare delivery reflected the thought and policies of the time. It was thought that assimilation of American Indians and Alaskan Natives was the best policy, and healthcare services were often provided off-reservation. This practice was detrimental to many patients who did not wish to be removed from their community. The OIA built the first modern Indian hospital in 1884. It was located in the Oklahoma territory. In 1885, more hospitals were built for the Menominee and Osage Reservations.

As Indian boarding schools became the new policy, many hospitals were built to serve the students. Boarding schools that were established off-reservation were considered by the federal government to be successful tools of assimilation as American Indian children were educated away from their homes and families and could then be “civilized” as their Native traditions were not allowed to be followed in the schools. The Indian school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, had many of its students die or become infected from tuberculosis during its first year of operation. General Richard Pratt, who was head of the school, went on to request “healthy children” for subsequent years. Carlisle Indian School Hospital was then established. The hospital provided health care to the boarding school students and also served as a training facility for American Indian women to become nurses (Dejong 2010).

There was also tension between American Indians who practiced traditional healing. Many tribal members relied upon these healing practices as cures for illnesses. Western medicine and the physicians of the time saw no benefit to such practices. It is not surprising then that when Western medicine was introduced to American Indian communities, it was often met with fear and misunderstanding. The tribal community did not trust many physicians who were charged with providing care to American Indians, and it would often be difficult to provide care. These fractures were exacerbated by the general distrust that remained at the time between American Indian populations and the federal government. A distrust that grew from the shared experience of American Indians who saw firsthand the negative effects of treaties being broken or dishonored, in addition to numerous failed governmental policies as well as forced removal.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the cultural gap continued and at times widened between American Indian healing culture and medicine and Western medicine. This gap was so wide that there was a ban on traditional healers at most federal hospitals and clinics that were established on reservations. The distrust of Native healing practices was also prevalent as American Indian physicians were largely educated in white-dominated medical schools where traditional healing and knowledge were not taught or practiced. Western doctors and scholars of the time wrote many disparaging articles that dismissed traditional healing and healers, known as “medicine men,” as quackery and quacks. It was also quite ironic that during this period, many medicines or cures marketed as “Indian cures” were popular among the general public.

Around two dozen treaties were ratified between American Indian tribes and the federal government that explicitly called for health services in exchange for land before the treaty-making period ended with the passage of the Indian Appropriation Act of 1871. While progress was made with the vaccine program, the congressional action regarding preventative medicine ceased until the latter part of the nineteenth century. The healthcare policy of the nation was moving toward a more institutionalized approach during this time as well, and American Indian healthcare services, and in particular, policy, mirrored the national example as large hospitals began to open, and the standards of practice for medical care were also established and enforced (Rife and Dellapenna 2009).

These calls for more resources and funding by many in Indian boarding schools and the OIA went largely unanswered as Congress was preoccupied at the time, breaking up the reservations in order to further advance the assimilation policies of the government. In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, which divided up the reservation and allotted land to American Indians with the goal of the Indians becoming successful farmers. In 1892, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Thomas J. Morgan (1889–1893), called upon Congress, “in the name of humanity,” to provide funding for new hospitals at every agency and boarding school because their absence was “a great evil, which in [his] view amount[ed] to a national disgrace” (Rife and Dellapenna 2009, 5).

In 1908, a national tuberculosis expert, Dr. Joseph Murphy, was appointed to organize and head the newly created Indian Medical Service. This was not the first (and would not be the last) attempt to reorganize health services and delivery to American Indians and Alaskan Natives, though it did mark the beginning of permanent medical services for Indian country being established (Dejong 2010). These services continued to be administered by the Indian Service (which became the modern Bureau of Indian Affairs). Meanwhile, the OIA faced a lack of funding and an overall lack of resources and medicine, which made it difficult to improve the health of American Indians and Alaskan Natives (Dejong 2010). In 1912, the acting chief medical supervisor of the OIA, Robert G. Valentine (1909–1913), requested that Congress provide an additional $253,350 for the purpose of “increasing the efficiency of the medical and sanitary work among the Indians” (Rife and Dellapenna 2009, 6).

Valentine went on to cite studies that confirmed the terrible state of health for American Indians and Alaskan Natives as well as the large deficit of resources the OIA and its physicians were facing. Congress was not convinced of this study. In August of the same year, the United States Public health Service (USPHS) was commissioned to “conduct a thorough examination as to the prevalence of tuberculosis, trachoma, smallpox, and other infectious and contagious disease among the Indians of the United States” (Rife and Dellapenna 2009, 6). The survey was exhaustive, and 39,231 Indians were examined (Rife and Dellapenna 2009). It confirmed the previous OIA findings, and Congress responded with minimal annual increases in OIA funding.

The Spanish Influenza outbreaks of 1918 and 1919 were especially detrimental to American Indian and Alaskan Native populations. The USPHS sent ten of its Commission Corps officers to help stop the outbreak, and their interventions were successful. The House Committee on Indian Affairs then argued that the USPHS should take control over Indian health. The OIA and the U.S. Surgeon General objected to this transfer. In November of 1921, Congress responded to the needs of Indian health care with the passage of the Snyder Act (42 Stat. 208). The Snyder Act was a huge step toward meeting the needs of American Indian and Alaskan Native health care, and although the legislation allowed for the permanent appropriation of Indian health care, no standards were provided in order for progress toward healthcare services and administration to be measured. New hospitals were eventually built, and the number of hospitals expanded from four in 1877 to 73 in 1922. In 1922, there were a total of 200 physicians and 100 “field matrons,” whose purpose was to raise living standards in Indian homes, provide hygiene and sanitation instruction, and provide emergency nursing services (Rife and Dellapenna 2009).

Sidebar 2: The United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps (USPHS)

The United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps is one of the seven branches of uniformed service in the United States. The USPHS was formed in 1798, after Congress created a Marine Hospital fund, which was created for the relief and care of seamen. The USPHS was officially recognized by Congress in 1889. The USPHS Corps officers’ duties were expanded to the prevention of infection diseases. The USPHS was originally open only to physicians, but it has now expanded to many other health professionals encompassing many disciplines. The primary mission of the Corps today is to protect and improve the health and safety of the nation. In order to fulfill this duty, USPHS officers also are deployed overseas to improve and maintain the health of American troops, and they also help to administer health care during natural disasters.

OIA then launched a nationwide anti-trachoma campaign. Although it was nationwide it was specifically targeted toward the American Indian and Alaskan Native populations. However, the campaign was ill-fated as risky medical procedures that involved the scraping of inner eyelids, or at times a procedure that involved the cutting of eyelid tissue, led to injury, infection, and permanent blindness and disability (Rife and Dellapenna 2009).

The OIA strived to become better organized in response to answering the American Indian and Alaskan Native health deficits of the time. Before that point, the OIA had been appointing individuals with little to no experience to be the administrators of its programs. This began with the army sergeants being charged with Indian health care in the 1800s, a pattern that continued into the twentieth century. The large majority of entry-level administrators of the time were American Indians and Alaskan Natives with little to no experience or education, who had risen up in the ranks of the OIA, with some even becoming department heads. These department heads, however, lacked the benefit of experience and training that was necessary to manage such a large program. Thus, when requests from physicians for more (or even adequate) supplies and medicine were made, these requests went up the chain of command, and ultimately untrained administrators who were more concerned with budgets than patients would decline to fulfill many of these requests (Rife and Dellapenna 2009).

In 1924, the secretary of the interior, Hubert Work (1923–1928), called for the appointment of a USPHS officer to serve as the chief medical supervisor as part of the newly formed division of Indian Health (established 1924). The chief medical supervisor’s position then had increased access to the commissioner. While this mandate seemed beneficial in theory, in practice the medical supervisor could only serve in an advisory role. The commissioner could then ignore the advice of the supervisor because the position was not legally bound to heed the supervisor’s advice (Rife and Dellapenna 2009).

Biographies

Dr. Carlos Montezuma (1865–1923)

Dr. Carlos Montezuma, or Wassaja, was a Yavapai (Mohave-Apache) physician, teacher, and author. He was born in Arizona in 1865. He graduated from the University of Illinois in 1884. He attended medical school at Northwestern University’s Chicago Medical College in 1889 and received his medical license during the same year. Dr. Montezuma was not only the first American Indian to graduate from a university, but he was also the first American Indian to graduate from a medical school in the United States. Upon graduation, he became an Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) physician, and he served in mainly western posts. He also worked in the Carlisle Indian Hospital, located in Pennsylvania. During this time, he also taught courses in medicine in Chicago. He then began a private practice in 1896.

Among Dr. Montezuma’s many notable achievements, he was a founding member of the Society of American Indians (SAI), which was the first organization founded by American Indians to advance the American Indian population. He joined the Yavapai in their struggle to establish Fort McDowell Yavapai Reservation in late 1903. In 1905, he received national attention as he openly opposed the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) as well as the government policies regarding American Indians. He opposed assimilation policies and once called for the complete abolition of OIA in the newspaper Wassaja (his name, which is the Yavapai word for “signal”), which he also published and authored from 1916 to 1923. The newspaper continued to call for an end to the BIA and the OIA, and also served as a platform to promote the civil rights and advancement for American Indian peoples. Dr. Carlos Montezuma passed away on January 31, 1923, from tuberculosis. He was buried at the Fort McDowell Indian cemetery in Arizona. In the 1970s, there was a rediscovery of his legacy and his work. In 1996, the Fort McDowell Indian Reservation dedicated its new healthcare facility to Dr. Montezuma. Its official name is the Dr. Carlos Montezuma, Wassaja Memorial Center. The University of Illinois announced in 2015 that its newest residence hall would also be named in his honor.

Dr. Charles Alexander Eastman (1858–1939)

Dr. Eastman (Santee Sioux) or Ohiyesa was a pioneering American Indian physician and author. He was born on a reservation near Redwood Fall, Minnesota, in 1858 and because of the “Sioux Uprising of 1862,” he was separated from his father, brothers, and sister. He then lived the traditional nomadic life with his grandmother and uncle. He was first educated in a day school, where he was very unhappy and so badly did not want to have a traditional haircut that he attempted to run away. He received a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth College in 1886 and went on to earn his medical degree from Boston University in 1889. While studying back east, he made many connections with prominent and influential individuals and used those to secure his first position as a physician on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

Dr. Eastman soon began working as a physician for the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA). He worked on the Pine Ridge Indian reservation in South Dakota in this capacity and then served the Crow Creek Reservation of South Dakota as a government-employed physician. He treated many of the survivors of the Wounded Knee massacre near Pine Ridge in January 1890. In 1893, he left his position at the PIA and he became politically active. He then gained widespread recognition for his work as an author, a poet, and an activist and reformer. In 1897, he served in Washington, D.C., as the legal representative and lobbyist for the Sioux tribe. During the 1920s, he served as a reservation inspector for the federal government. Like Dr. Montezuma, he also called for the end of the OIA. He was a cofounder of the Boy Scouts of America, and he succeeded his colleague, Dr. Montezuma, as president of the Society of American Indians (SAI). In his later years, he lived in what was described as a “primitive cabin” on the north shore of Lake Huron. He passed away on January 8, 1939, at the age of 80.

Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte (1865–1915)

Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte was the first American Indian woman physician. She was also the first Native, female physician to be employed by the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA). She was born Susan LaFlesche in 1865 on the Omaha Reservation in Omaha, Nebraska, to Chief Joseph La Flesche (Iron Eyes) and his wife, Mary (One Woman). Her desire to work in medicine began when as a young child she saw an older Native woman die because the local doctor, who was white, refused to give them care. She graduated from in 1889 from the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, which she had attended on an OIA scholarship, and the Connecticut Indian Association, which made her the first person male or female to receive federal funding for her education. After only two years in a three-year program, she graduated at the top of her class. She completed an internship in Philadelphia and then returned home to Omaha to serve her tribe as an OIA physician. She helped to serve 1,200 Omaha Indian boarding school students. From 1891 to 1893, she served as a “medical missionary” for her tribe. For this position, she would often have to travel across the reservation in Omaha, where she would make house calls, while also seeing patients in her office.

In 1894, Dr. La Flesche entered private practice and married. In 1906, she led a group to Washington, D.C., where they called for the banning of alcohol on Indian reservations. While raising two sons, she saw and treated both Native and non-Native patients. She opened a hospital in the reservation town of Walthill, Nebraska, in 1913. Her entire career was dedicated to trying to improve the health conditions of the Omaha tribe. She corresponded frequently with the commissioner of Indian affairs to try to achieve that goal. She was very well received by many in her home state of Nebraska, and there were many newspaper articles promoting and describing her work. She passed away on September 18, 1915. The hospital she founded now houses a museum that is dedicated to both her life and the Nebraska Omaha and Winnebago tribal peoples.

DOCUMENT EXCERPTS

Death from Smallpox

Fort Clark’s superintendent, Francis Chardon, recorded the death and despair of the Mandan Indians from smallpox in his journal in 1837. The following is an excerpt from his journal.

Consummation of the Government Policy of Removal. Prevalence of the Small-Pox amongst the Western Indians. 1837. M. Van Buren, President. The Summer of 1837 is rendered memorable in Indian history by the visitation of one of those calamities which have so much reduced the Indian population, viz: the ravages of the small-pox, which then swept through the Missouri valley. The disease was introduced among them from a steamboat, which ascended that river from the city of St. Louis, in July. On the 15th of that month the disease made its appearance in the village of the Mandans, great numbers of whom fell victims to it. Thence it spread rapidly over the entire country, and tribe after tribe was decimated by it.

The Mandans, among whom the pestilence commenced, are stated to have been reduced from an estimated population of 1600 souls to 125. The Minnetarees, or Gros Ventres, out of a population of 1000 persons, lost one-half their number. The Arickarees, numbering 3000, were reduced by this pestilence to 1500. The Crows, or Upsarokas, lost great numbers, and the survivors saved themselves by a rapid retreat to the mountains. The Assinaboins, a people roughly estimated at 9000, were swept off by hundreds. The Crees, living in the same region, and numbering 3000 souls, suffered in an equal degree. The disease appears at length to have exhausted its virulence on the Blackfeet and Bloods, a numerous and powerful genus of tribes. One thousand lodges are reported to have been desolated, and left standing, without a solitary inhabitant, on the tracts and prairies, once the residence of this proud and warlike race: a sad memorial of this dreadful scourge.

Visitors to these regions, during the year when this dread pestilence was raging there, represent the Indian country as being truly desolate. Women and children were met wandering about without protection, or seated near the graves of their husbands and parents, uttering pitiable lamentations. Howling dogs roamed about, seeking their masters. It is reported that some of the Indians, after recovering from the disease, when they saw how it had disfigured their faces, threw themselves into the Missouri river.

Language, however forcible, fails to give an idea of the reality. On every side was desolation, and wrecks of mortality everywhere presented themselves to the view. Prominent among these was the tenantless wigwam: no longer did the curling smoke from its roof betoken a welcome, and its closed door gave sad evidence of the silence and darkness that reigned within. The prairie wolf sent up its dismal howl, as it preyed upon the decaying carcasses; and the lonely traveler, as he rapidly passed through this scene of desolation and death, was frequently startled by the croaking of the raven, or the screams of the vulture and falcon, from trees or crags commanding a view of these funereal scenes.

Source: Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, History of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Their Present Condition and Prospects, and a Sketch of Their Ancient Status, 1857. Report of smallpox in 1837, pp. 486–87.

Health of American Indian Children in Boarding Schools

During the boarding school era, the health needs of the students became a concern, especially as trachoma and tuberculosis ravaged the boarding schools. This report details the health status of one such boarding school in New Mexico.

I have the honor to submit annual report for the fiscal year 1909 on affairs of the Albuquerque Boarding School, nine day schools and the pueblos under my jurisdiction. The school is two miles north of the post office and outside of the city limits. The enrollment for the year was 359 and the average attendance 326. There were about two boys to one girl enrolled. The pupils came from the various pueblos under the control of the Albuquerque school, from the reservation and non-reservation Navahos, three from the Apache reservation and one Miami from Oklahoma.

The health of the pupils has been good. There were no deaths during the year. Trachoma and other eye troubles have been treated by the school physician with excellent results; 52 cases were satisfactorily operated on for trachoma. During the months of December, January and February the school was under strict quarantine against city and surrounding country owing to the the [sic] prevalence of scarlet fever in the city and country. The disease did not reach the school, but one case developed in the pueblo of Isleta. By placing this party and others who had been exposed under strict quarantine, the spreading of the disease was prevented at that place.

Source: United States. Office of Indian Affairs. Annual report of the commissioner of Indian affairs. Reports Concerning Indians in New Mexico. Albuquerque, N. Mex., August 12, 1909, p. 1.

The Congressional Authorization of Health Care for American Indians

The Snyder Act was signed into law in 1921, and for the first time, the basic authorization of health care to American Indians was delegated by Congress. It serves as the basis for broad American Indian healthcare policy. The full text of the act appears below.

Public Law 67–85 The Snyder Act 25 U.S.C. 13. November 2nd, 1921 Section 13.

Expenditure of appropriations by The Bureau of Indian Affairs, under the supervision of the Secretary of the Interior, shall direct, supervise, and expend such moneys as Congress may from time to time appropriate, for the benefit, care, and assistance of the Indians throughout the United States for the following purposes:

General support and civilization, including education. For relief of distress and conservation of health. For industrial assistance and advancement and general administration of Indian property. For extension, improvement, operation, and maintenance of existing Indian irrigation systems and for development of water supplies. For the enlargement, extension, improvement, and repair of the buildings and grounds of existing plants and projects. For the employment of inspectors, supervisors, superintendents, clerks, field matrons, farmers, physicians, Indian police, Indian judges, and other employees. For the suppression of traffic in intoxicating liquor and deleterious drugs. For the purchase of horse-drawn and motor-propelled passenger-carrying vehicles for official use. And for general and incidental expenses in connection with the administration of Indian affairs.

Notwithstanding any other provision of this section or any other law, postsecondary schools administered by the Secretary of the Interior for Indians, and which meet the definition of an ‘‘institution of higher education’’ under section 101 of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. 1001), shall be eligible to participate in and receive appropriated funds under any program authorized by the Higher Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. 1001 et seq.) or any other applicable program for the benefit of institutions of higher education, community colleges, or postsecondary educational institutions.