Defending the West, 1840–1890

Apache Resistance, 1849–1886

Ramon Resendiz and Rosalva Resendiz

Chronology

1835 |

Bounties for Indian scalps are made by the government of Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico. |

|

1845–1848 |

Mexican American War dispute over the U.S.–Mexico boundaries. |

|

1848 |

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is signed. The Rio Grande River becomes the U.S.–Mexico boundary, and the United States becomes responsible for protecting Mexicans from Indian raids. |

|

1848–1849 |

Apaches raid and kill Sonorans. |

|

1850 |

Massacre at Ramos. |

|

1851 |

Massacre at Esqueda. |

|

1851 |

The Carrasco Massacre: Geronimo’s family are killed. |

|

1852 |

Mangas Coloradas and other Apache chiefs make a treaty with Major John Greiner and Colonel E.V. Sumner. |

|

1853 |

Fort Atkinson Treaty is signed by Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Indians to secure the Santa Fe Trail for white settlers. |

|

1861–1865 |

Civil War between the Union and Confederate states. |

|

1861 |

The discovery of silver and gold in Apacheria leads to more intruders and more conflict. |

|

1861 |

Mangas Coloradas goes to war against Americans and Mexicans. |

|

1861 |

Bascom Affair: Chief Cochise is wrongly accused of kidnapping a child. |

|

Mangas Coloradas and Cochise attack Union soldiers in the Apache Pass Battle. |

||

1863 |

Mangas Coloradas is killed. |

|

1866 |

Commanding General Sherman argues for the removal of all tribes in order to provide an Indian-free corridor across the United States to be used by white settlers. |

|

1866 |

Congress passes a resolution that would take away land from the Indians in order to complete the railroads. |

|

1866 |

Army Reorganization Act of 1866 allows for Indians to enlist in the army or become scouts. |

|

1866 |

The 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry units are created by Congress. The Cavalry and Infantry units are composed of black soldiers (Buffalo soldiers) with white officers. |

|

1867 |

Medicine Lodge Treaties are made with Native Americans for their relocation to reservations. |

|

1868 |

The Fourteenth Amendment is ratified. Citizenship is to be granted to every person born in the United States and guaranteeing equal protection under the law. |

|

1869–1877 |

President Ulysses S. Grant institutes a peace policy toward Indians but also oversees military actions against the Apaches. |

|

1870s |

Bison are slaughtered to starve the Apaches and force them onto reservations. It is estimated that almost three million are killed. |

|

1871 |

Camp Grant Massacre. |

|

1871 |

Indian Appropriations Act ends the recognition of Indian tribes as sovereign nations. New treaties would treat Indians as individuals and wards of the government. |

|

1872 |

Cochise-Howard Treaty. |

|

1873 |

Lipan Apaches are killed in the Mackenzie Raid/Massacre or “Dia de los Gritos/Day of the Screams.” |

|

1874–1877 |

Black Hills Gold rush brings miners and settlers, which further increases conflict in Apacheria. |

|

1874 |

Texas Rangers are recommissioned in order to fight the Comanche, Apache, and Kiowa Indians. |

|

1874 |

The U.S. Army is authorized to enter Indian reservation land in pursuit of resisting bands of Indians. |

|

Camp Verde Reservation is closed, and the Apaches are moved to San Carlos Reservation. |

||

1879 |

The Women’s National Indian Association is founded by white reformers to promote assimilation and Christianization of Indians. |

|

1879 |

Victorio declares war. |

|

1880 |

Victorio is killed in Mexico, and his lieutenant Nana seeks revenge. |

|

1881 |

The last of the Lipan Apache warriors are captured in Texas under the false promises of food. Over 200 Apaches are taken, and their chiefs are killed. |

|

1881 |

Nana goes on a warpath from Mexico to New Mexico in vengeance. |

|

1881 |

Nakaidolini, an Apache medicine man, advocating resistance to white settlers’ encroachment, is killed by U.S. soldiers. |

|

1881 |

Helen Hunt Jackson writes and publishes A Century of Dishonor, in an attempt to call attention to the inhumane treatment of Indians. |

|

1882 |

Indian Rights Association is founded by white male reformers advocating assimilation and citizenship. |

|

1882 |

Battle of the Big Dry Wash: White Mountain Apaches take their last stand in Arizona and fail in their ambush of the 3rd and 6th Cavalry. |

|

1882 |

Casas Grande Massacre. |

|

1882 |

Geronimo breaks into San Carlos, killing two law enforcement officers and breaking out Apaches. |

|

1883 |

Geronimo, Naiche, and Nana surrender to General Crooks. |

|

1885 |

Geronimo and Naiche escape from San Carlos. |

|

1886 |

Geronimo and Naiche surrender to General Crooks and then change their minds and finally surrender to Lieutenant Gatewood. |

|

1887 |

The Dawes Act is passed. This act allows for reservation land to be given to individuals, for the subsequent sale of that property. |

|

1913 |

Prisoners of war are released. |

The Apaches

The Apaches lived in the land known today as Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, down to Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico, and the Sierra Madre mountains. They lived and hunted from the Colorado River, to the Pecos River, and the Texas hill country, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, crossing over the Rio Grande River and into Mexico. From 1849 to 1865, the Apaches fought off a series of invasions by settlers on their ancestral lands. Apacheria, the land of the Apaches, belonged to tribes who were composed of bands related by the Athabascan language. The Apaches include the Plains Apaches, Lipan Apaches, Mescalero Apaches, Western Apaches, Jicarillas, Chiricahuas, and Navajos. They have been given many names, but they call themselves the Dine or the N’de (Induh), “the people.” With the conquest of the Americas, imperialism and expansionist policies which sought to acquire Apacheria at any cost, for the Apaches, who resisted, that meant they would be faced with their attempted extermination and genocide at the hands of various colonial powers.

The Apache wars were led by the Chiricahuas. While most of the Apaches had settled onto reservations, the Chiricahuas fought the Mexicans, the U.S. military, and white settlers. The Apaches were persecuted by both the Mexican government and the U.S. government. In 1848, Mexico lost the war to the United States and signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. As part of the terms, the United States was charged with protecting the Mexican people from Apache raids, as well as placing the Apaches on reservations to live a life of farming. In the beginning, some of the Apaches made peace treaties with the U.S. government, however, racist policies, treachery, and corruption by U.S. agents resulted in conflict and vengeance.

Some of the Apache tribes agreed to move into reservations, as long as they were allowed to stay in their homeland, but the United States broke their treaties when white settlers wanted those lands. The peaceful Apaches were displaced once again and relocated to land that could not provide a living for them. Apaches were not war-like, but they did believe in vengeance and therefore, for every act of treachery that they received at the hands of the Mexican people, white settlers and/or the U.S. government, the Apaches declared war. Again and again, Apaches who sought peace were continuously faced with betrayal.

The Apaches were a matrilocal and matrilineal culture. When a man married a woman, he moved to her family’s tribal band. As a result of this type of marriage, the Apaches had strong bonds and alliances with many of their fellow tribes and bands, which were called upon during times of war and when seeking to hide from the U.S. government. Gender roles in the Apache culture were interdependent and both were valued. There was a sexual division of labor, but a female was allowed to become a warrior, as was the case with Lozen, Chief Victorio’s sister. Their sexual division of labor did not place women in a subordinate position. Instead, both roles were considered as complementary, with women managing economic activities, wealth, food preparation, child rearing, and house building. Men hunted, raided, waged war, and dealt with external relations. As conflict and war grew in Apacheria, the tribes and bands were forced to take their families on raids and war expeditions. This led to the increased participation of wives as warriors, fighting alongside their husbands. And if their husband was killed, the widow took his place as a warrior. Regardless of the gender-role training that girls underwent, all Apaches were prepared for war and were trained as such.

Treachery and Massacres

Although the Apaches had encountered the Spanish explorers, Apache conflicts began with the Mexicans and the United States in the 1830s. In 1835, the Sonoran government established the scalp bounty law, offering 100 pesos for a warrior’s scalp. Two years later, the Chihuahan government further offered 50 pesos for an Apache woman’s scalp, and 25 for a child’s. This became a genocidal enterprise in which U.S. citizens began to engage as well. Scalp hunters such as James Kirker incited revenge war parties from chiefs such as Mangas Coloradas and Cochise. The more that Apaches were killed and scalped, the more retaliatory killings from the Apaches.

Sidebar 1: Warriors

At the age of 15 or 16, young men were initiated into the ways of the warrior. The boy underwent physical training and learned the skills of war. He became an apprentice before becoming a warrior by serving on four raids or war parties. As an apprentice, he was responsible for helping his mentor prepare his meals and/or his weapons. Apprentices were trained for physical endurance, knowledge of their land, and field actions. As an apprentice, the boy did not engage in the raid or war directly. He stayed behind and was protected by the other warriors.

Warriors engaged in raiding and war parties. Raiding was done as an economic necessity for survival, while going to war was a result of an injury done to the them. For each act of treachery and death to the Apaches, war vengeance was the outcome. Vengeance was called upon by the women and would lead to a war dance in which warriors were invited to join. Joining a war party was voluntary, but not joining was considered an act of cowardice.

Before contact with the Europeans, their weapons consisted of bows, arrows, spears, clubs, stone knives, wrist-guards, and shields. The arrows were made from hard wood, and the sharpened tips were hardened by fire. Poison, made from deer’s blood and mixed with poisonous plants, was also sometimes used on arrows. After contact with the Europeans, Apache warriors traded with settlers and became extremely proficient in the use of firearms. Apaches adapted and learned to use the rifles most effectively in warfare. They noted that for shorter ranges, Henrys or Winchester repeating rifles were more effective, while single-shot rifles such as Springfields or Remingtons were better for longer ranges (Watt 2011a). Not only were they excellent marksmen, they also were great riders. All Apache women and men were great horse riders and tamers. They could ride their horses on the side, so as to not be noticed when retreating from a raid or war party.

In the summer of 1850, friendly Apaches were tricked by Mexicans from the city of Ramos. For many years, the Apaches had traded with these villagers, and when invited to join in the festivities and drink as much as they wanted, they went trustfully. When the Apaches had drunk too much and fallen asleep in the camp, they were brutally killed by soldiers and villagers with clubs. Their scalps were sold for money. The women and children were captured were sold into slavery. Apaches were always seeking peace, but this type of treachery resulted in their continuous seeking of vengeance. A war expedition was planned by Cuchillo Negro several months later, in which Chief Mangas Coloradas and Cochise led vengeance with 175 warriors (Betzinez 1987).

A year later, after the Battle of Ramos, Apaches were betrayed by the town of Esqueda. The Apaches visited the town for trading, and the Mexican people welcomed them. As in the case of the town of Ramos, they enticed the Apaches with mescal or aguardiente (liquor) until they were “dead drunk.” The men were slaughtered, and the women and children were sold into slavery. Most of the Apaches who were kidnapped died in captivity in California, except for one woman, Dilchthe, who was able to escape and walk back to her people (Betzinez 1987).

On March 5, 1851, Mexican General Carrasco massacred women and children while their warriors were away. The Chiricahua Apache bands living near Janos, Chihuahua, Mexico had made a peace agreement (June 24, 1850) with officials from Chihuahua, but not with the Sonora state, which blamed the Apaches for recent attacks. By the end of 1850, it was estimated that Apaches had killed 111 citizens from Sonora. In retaliation, General Carrasco’s army surprised two rancherias (villages), killing 21 Indians and capturing 62 women and children, who were sold into slavery. In this massacre, Geronimo’s family were killed, and it was this event that led to Geronimo’s hatred of Mexicans, which resulted in much vengeance by the future chief.

On April 30, 1871, innocent women and children were slaughtered while they slept near Camp Grant. Aravaipa and Pinal Apaches surrendered and placed themselves under the protection of Captain Whitman. Citizens from Tucson, Arizona, Mexicans, and white Americans planned the murder of the Apaches, along with the Papago Indians, who were enemies of the Apache people. They slipped into the camp and killed approximately 108 women and children, including babies and two boys. When the bodies were found, sexual violence was evident, as some women had been raped before being murdered. President Grant was outraged by the actions of civilians and demanded that the killers be arrested and put on trial. The defendants were pronounced not guilty, although they had admitted to such atrocities. The 29 children taken captive were either sold, enslaved, gifted, or adopted. In 1875, the survivors under Chief Eskeminzin were attacked again, resulting in more violence.

On May 18, 1873, Captain Mackenzie rode into Mexico, without permission from the Mexican government, to ambush and slaughter Kickapoos, Lipans, and Mescalero Apaches. The Kickapoo village was first destroyed, and from there the army went from the Lipans to the Mescalero village, where both male and females fought. Many Apaches escaped to the mountains and reconvened at other camps. The Apaches remembered Mackenzie’s raid as “Dia de los Gritos” (the Day of the Screams). Women, men, and children were killed by gunshots or bayonets. The villages were destroyed and burned. Many Apaches hid in holes, covered by weeds, which was a technique they used to hide from enemies. Forty women and children were taken captive. Seventy-five Lipan and Mescalero warriors regrouped near a creek. On October 6, 1873, Lipan Apaches set out on a warpath, seeking revenge from all frontier towns.

Chiefs of the Resistance

The Apache chiefs had tried to find peace with the Mexican and U.S. governments, but due to continuous treachery, broken treaties and corrupt agents who starved the Apaches on the reservations, the chiefs rose against the U.S. government, the Mexicans and the white settlers. The situation became worse when they were again displaced from the reservations that were in their homelands. Gold was found, and settlers wanted the Apache lands. Railroads wanted to set up their tracks. Ranchers wanted to fence cattle in. Apaches were dispossessed of their homeland and forced to fight against the Mexican government, the U.S. government, and all the settlers encroaching on their territories.

Warriors became chiefs by demonstrating bravery and skill, as well as possessing a power or spiritual gift. Most chiefs were medicine men, and because of their spiritual power, they inspired loyalty. There were many chiefs who created alliances and fought, beginning with Pisago Cabezon to Geronimo’s and Naiche’s final surrender in 1886.

Resistance at the Turn of the Century

In 1881, Apaches left the San Carlos reservation, led by Geronimo, who went to join Chief Juh, Nana and Naiche (Cochise’s son) in the Sierra Madre. As a young man, Geronimo (Goyakla) fought under Mangas Coloradas in the late 1840s and 1850s. While away on a raid, he lost his family in the Carrasco Massacre of 1851. In this massacre, Geronimo lost his mother, wife, and children. That initial betrayal fired Geronimo’s hate for the Mexican people for the rest of his life. Although Naiche, Cochises’s son, was the hereditary leader of the tribe, Geronimo was considered the true leader. Geronimo was a shaman with the power to foretell the outcome of a battle, and the ability to control men.

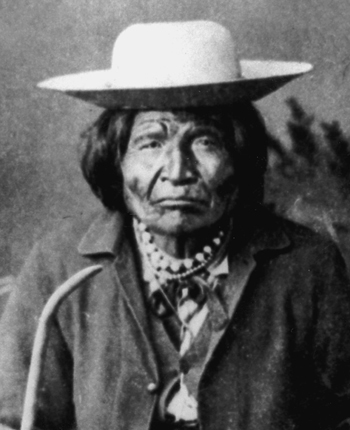

Chiricahua Apache leader Nana fought alongside Mangas Coloradas and was married to a sister of Geronimo. After defeat in 1886, the Chiricahuas were prisoners of war in Florida and Alabama. They were not allowed to return to their homelands but in 1894 were relocated to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, part of Indian Territory, where Nana died two years later in 1896. (National Archives)

In 1875, the Apaches were moved from Ojo Caliente and forced to relocate in the San Carlos reservation. Victorio, Nana, Loco and Geronimo were among this group. The men were placed in shackles and loaded into wagons. Escorting the Apaches were the Buffalo soldiers of the 9th and 10 Cavalry. The cavalry was composed of newly freed blacks, under the command of white officers. At San Carlos, many feuding tribes and bands were placed together, causing further conflict. San Carlos was inhospitable and plagued with disease.

In 1882, Geronimo attacked San Carlos, killing two law enforcement officers. Over 100 Apaches joined him and followed Geronimo to Mexico to Juh’s (Long Neck) camp in the Sierra Madre. Another story said that Chief Loco and his people were forced to leave with Geronimo. Chief Loco had been living on the San Carlos Reservation peacefully since the days of Victorio. Chief Loco and his people became “hostiles” and were forced to join the war.

That same year, Geronimo and Juh attempted to make peace with the Mexicans from Casas Grandes. A third of their people made camp outside of Casas Grandes and sent a woman to request peace talks. The Apaches and Mexicans met and were told that all previous hostilities would be forgiven. The Mexicans provided liquor, and while the Apaches rested in their camp, they attacked them and killed them. Geronimo and Juh were able to escape from the Casas Grande massacre.

After the Casas Grande incident, Juh and Geronimo split the band. Juh went into hiding in the Sierra Madre, while Geronimo headed west to raid and attack Sonora and then proceeded to raid into the United States to acquire ammunition. After the successful attacks, Juh and Geronimo rejoined and camped together for a few weeks. Juh then returned to the Sierra Madre and Geronimo continued onwards to raid Sonora. After a few months, Juh rejoined Geronimo again. Juh had been attacked by the Mexicans and had lost his wife and many of his people. Geronimo, along with other chiefs, continued to fight. In the Battle of the Canyon, they ambushed Mexican soldiers and then retreated into the Sierra Madre. Soon after, they planned to attack Chihuahua and take prisoners, which they could exchange for Apaches which had been captured at Casas Grande and in the attack against Juh. They were unable to exchange the prisoners, as Geronimo foretold that their base camp had been captured by General Crook and therefore left to the aid of their people.

Nana, Loco, Geronimo, and Naiche surrendered to General Crook, and 300 Apaches returned to San Carlos in 1883. According to their oral history, the female warriors Lozen and Dahteste negotiated their return to San Carlos’s Turkey Creek area (Perdue 2001). Juh did not go to the reservation, but his people did. Juh had died. One version says that he had gotten drunk and fallen off a cliff with his horse (Betzinez 1987), while another story simply states that he drowned, after advising his people to fight to the death (Ball 1988).

In 1885, it was rumored that the leaders of the Apaches were going to be sent to Alcatraz, a prison in California. Geronimo and Naiche left the reservation with 140 followers and 40 warriors, including Lozen and Dahteste. On March 25, 1886, Lozen was sent to negotiate peace with General Crook and requested that their people be allowed to return to San Carlos to be with their families. General Crook agreed to those terms, and Geronimo’s band surrendered. Geronimo and Naiche did not trust that the U.S. government would abide by those conditions and left with Lozen and a few followers.

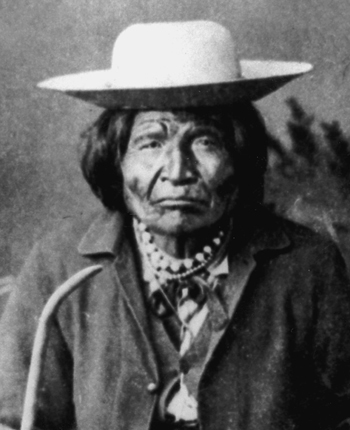

Chiricahua Apache prisoners, including Geronimo (first row, third from right), sit on an embankment in Arizona outside their railroad car in 1886. Before Geronimo’s surrender on September 4, 1886, he and his forces were the last independent Native American warriors to refuse to acknowledge the presence of the U.S. government in the West. In 1875 the Apache faced forced removals. (National Archives)

Geronimo had been correct in those assumptions. General Philip Sheridan and President Grover Cleveland did not approve of the terms. The Apache leaders and their people were to be imprisoned. General Crook was then replaced by General George Miles, who sent 5,000 soldiers to capture 36 Apaches. By August 1886, Lozen and Dahteste were sent to open up negotiations for surrender and met with Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood. There were no negotiations. All of the Apaches at San Carlos, along with all the Apache scouts who had worked for the U.S. government, were sent to Florida. Since the Apaches wanted to be with their families, on September 3, 1886, Geronimo’s and Naiche’s band surrendered. Loco, Geronimo, Naiche, Lozen, and Nana became prisoners of war. By 1890, over 100 of the 500 Apaches sent to Florida had died due to disease. By 1913, they were finally allowed to return to their people, but by that time, many more had died of disease.

Guerrilla Warfare

Guerrilla warfare tactics made it extremely difficult for the U.S. military to truly defeat the Apache people. In order to capture them, the U.S. government had to employ and rely on Apache scouts. It is noted that one of the best warriors and leaders of guerrilla warfare was Victorio, who knew how to strategize effectively. Victorio’s success is credited to the tactical flexibility, adaptation, and close-knit relationships of his people. Individuals were always prepared to act decisively.

Sidebar 2: Principles of War

For Native Americans and the Apaches, the goal in warfare was to inflict the most damage while suffering minimum loss. In order to achieve this, Apaches rigorously trained both males and females. Although there was a division of labor by gender, both women and men were expected to undergo training in physical endurance, hunting, fighting, and weaponry. But in order to ensure their survival, intimate knowledge of their land and environment was necessary. Apaches learned where to find water and food in places where others could not. They also learned the art of concealment. Apaches protected their families by hiding in mountains in difficult-to-reach terrain.

One integral aspect of Apache culture was raiding, an economic activity that provided sustenance and wealth. Raiding involved the seizing of property from enemies, but the goal was never to kill unless provoked. The goal of warfare was to kill the enemy, and this was to avenge the death or treachery inflicted on their people. Both males and females participated in raiding and warring.

The wisdom of the elders was respected, but to become a leader, warriors had to prove themselves. Leaders with spiritual power became the chiefs and gained a following, as it was believed that they were favored by the spirit world.

The Apaches had two main principles that helped them in guerrilla warfare: tactics and strategy. Apaches strategized and planned their targets so as to avoid any casualties, always ensuring that there were various exit strategies. Their tactics in warfare involved the use of decoys as well as ambushes with a quick retreat.

Warfare Techniques

The three main techniques used by the Apaches were evasion, ambush, and attack. Evading the enemy was crucial to survival when being pursued. Apaches were always prepared to scatter and regroup in case of an emergency, with a prearranged location determined. This gave the Apaches a higher chance of survival. Knowledge of the environment was necessary in order to conceal themselves from the enemy, as well as to find food and supplies. Decoys were also used to help Apaches escape, sending groups of warriors in an opposite direction or leaving false trails for the scouts. False trails were left by cutting the telegraph lines and hiding the damage to make it difficult for the enemy to find the problem or doing the opposite and making it evident that the line had been destroyed. In order to slow down the pursuit, the army horses and mules were killed or crippled. When moving, the main group travelled with guards around them. There were guards on the left and right, as well as flanks of guards in the front and rear. The guards were located many miles away in order to be able to maneuver the main group into hiding in case of a threat.

Biographies

Pisago Cabezon, Mangas Coloradas and Cochise

Pisago Cabezon, Mangas Coloradas, and Cochise and were some of the most notable chiefs who were part of the beginning of the Apache Wars. Pisago Cabezon was a prominent leader, and Cochise’s father, Mangas Coloradas (“Red Sleeves”), was known as a fierce warrior. It was said that he earned that name because his sleeves dripped with blood, while another version says that it was his fondness for wearing the enemy’s colorful clothing and uniforms.

In 1838, Pisago Cabezon sought peace with the government of Chihuahua and moved his people near Janos. For Pisago Cabezon, as well as for Mangas Coloradas and Cochise, that meant that they could not attack the people of Chihuahua, but they could still conduct their raids in Sonora. These attacks provoked much indignation from the Sonorans and led to a military campaign. Elias Gonzalez led an army and attacked the Apaches near Janos, killing 80 women and children. Their hair and ears, and the women’s genitals were cut off as trophies. This attack on innocent women and children led to another revenge war. Mangas Coloradas made a call for a war party and resumed the war with Mexico, killing people from Chihuahua and Sonora.

In 1846, after much more revenge killing had occurred, Pisago Cabezon sought peace from Chihuahua. Pisago Cabezon was approached by James Kirker, an old friend turned scalp-hunter, who volunteered to help Pisago Cabezon make peace with Chihuahua again. Cochise, his son, was wary of the white man and warned his father that it was rumored that James Kirker had become a scalp hunter, killing Apache and Mexican women and children. Pisago Cabezon, wanting peace, met with James Kirker outside Galeana, where they held festivities for three days. While Pisago Cabezon and his people slept drunk, they were clubbed to death. One-hundred-thirty Apaches were killed and scalped.

From this treachery, Cochise learned, “… the People had no friends … the White Eyes were just as false as the Mexicans … peace may be more deadly than war.… Power cannot save you, if you drink enough whiskey” (Aleshire 2001, 62). With the death of his father, Cochise turned to vengeance and rose as a leader in his tribe. Mangas Coloradas, Cochise, and Cuchillo Negro gathered 175 warriors and attacked Galeana, killing anyone in their path.

When Mangas Coloradas found out that there was a war between the United States and Mexico (1846–1848), the warriors of the Chiricahua continued their war on the Mexican people. Mangas Coloradas, Cochise, and Narbonna, a Mexican who had been adopted by the Apache and had risen to chief, continued their war with Mexico. By the late 1840s, the Apaches had forced many Mexicans to leave. In the State of Sonora, “twenty-six mines, thirty-nine haciendas and ninety-eight ranches” were abandoned (Sonnichsen 1990, 37).

Eventually, Cochise married Dos-teh-seh, “Something Already Cooked by the Fire,” who was Mangas Coloradas’s daughter. She had been trained in the arts of the woman, but also as a warrior. It was said that she also had the power, as her father, which included war strategy. Dos-teh-seh accompanied Cochise on raids until she became a mother but continued to provide counsel and guidance to him.

After the death of Pisago Cabezon, Cochise became a chief at a young age, by demonstrating his skills as a warrior and by providing food for his people. Cochise, as other chiefs, was a medicine man and gifted with spiritual power. It was said that bullets could not touch him. Therefore, many warriors aligned themselves with him.

While Mangas Coloradas and Cochise continued to attack the Mexicans, another chief sought peace and settled near Janos. Mangas Coloradas, and Cochise, honoring the peace treaty of Chief Yrigollen, focused their attacks on Sonora. Sonorans grew angry about the continuous raids and lashed out and attacked the peaceful Apaches at Janos. Twenty-one people were killed, as well as chief Yrigollen, and 62 Indians were captured and sold as slaves.

When the United States won the Mexican American War, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, the U.S. army approached Mangas Coloradas and informed the Apaches that their land was now American land. Mangas Coloradas was tactful and agreed to respect the Americans, but continued to wage war against the Mexican people in Sonora and Chihuahua. In January of 1850, 200 Apaches under Mangas Coloradas won a battle at Pozo Hediondo (“Stinky Well”), where they killed 26 soldiers and wounded 46 under the command of Sonoran Captain Pesqueira.

As white settlers came to Apacheria, conflict intensified, and the Apache fought Mexicans and Americans, at the same time trying to make peace. In 1861, Cochise was accused of kidnapping a child, Mickey Free. Cochise and some of his men were invited to speak with Lieutenant Bascom, who prepared an ambush and arrested them. They were invited to visit, and when Cochise’s party was inside the tent, soldiers surrounded it. Cochise escaped by cutting the tent, but his companions were kept as prisoners and eventually killed. Cochise began a war of revenge, for he had lost relatives at the hands of Bascom. Within two months, Cochise had killed 150 whites.

From 1861 to 1865, the United States was involved in a Civil War between the North and the South. During this period, Apaches had a respite from invaders. On July 15, 1862, Mangas Coloradas and Cochise confronted Union soldiers moving through the Apache Pass. Five hundred Apaches ambushed General James H. Carleton’s California Volunteers. Although the Apaches did not defeat the Union soldiers, it was an important battle as it was the largest gathering for the Apaches, with 500 warriors.

In 1863, Mangas Coloradas was captured by treacherous means and taken to Fort McLane, where he was placed under arrest and killed by two guards. The murder of Mangas Coloradas further exacerbated the hostilities against the military and the settlers in Arizona and northern Mexico. At the loss of his father-in-law, Cochise’s anger resulted in the loss of 5,000 American lives.

On October 13, 1872, Cochise made peace with the U.S. government and settled into reservation life in San Carlos. By June 1873, Cochise was dead. He had contracted malaria.

Victorio, Nana and Lozen

In 1870, Chief Loco and Chief Victorio (Bi-du-ya) agreed to enter a reservation in their homeland Ojo Caliente. By 1875, they were removed from their ancestral lands to the San Carlos reservation in Arizona, where conditions were intolerable. There was no grass and no game to hunt. The water was bad, and only cacti grew there. The area was infested with mosquitoes, which killed many Apaches through disease. Living in San Carlos became intolerable, and by 1877, Victorio left the reservation and returned to Ojo Caliente, while Nana (Kas Tziden), his second in command, went to the Mescalero reservation in New Mexico.

Victorio escaped from the San Carlos reservation in Arizona was due, in part, to a corrupt agent. Agent Godfroy was starving and freezing the Apaches to death. Victorio and Nana left for a Mescalero reservation, where the agent allowed them to stay, but feeling unsafe when law enforcement appeared, Victorio left for Ojo Caliente. With 60 warriors, Victorio attacked the army outside of Ojo Caliente to avenge the death of his kin, as well as to pressure the United States. Victorio hoped to pressure the U.S. government into honoring its promise to let his people reside in their ancestral lands. At the Mescalero reservation, Lipan Apaches were arrested, but eventually released by mistake, and when they had the chance they left and joined Victorio. General Edward Hatch suspected that Victorio was getting supplies from the reservation and ordered the Indians to be disarmed. He placed 250 men, women, and children under arrest. Other Apaches were able to escape, while the army shot at them. Those who survived joined Victorio as well.

On August 21, 1879, Chief Victorio declared war against the U.S. government. In his fight against the United States, he was accompanied by his sister Lozen, who was a respected female warrior and considered to be Victorio’s right hand. Victorio was believed to have the power of strategy, which his sister also possessed, while Nana was said to have power over rattlesnakes and ammunition.

Victorio was noted as one of the best warriors for being highly skilled in the art of guerrilla warfare. Apaches strategized and chose their targets carefully, always considering the safety of their families. They would ambush and quickly disappear, knowing quite well how to erase their trails. The military would pursue them, but catching up to them was difficult, since Apaches would hide in the mountains, where it was difficult for the army to enter. For the Apaches, success was determined by how much damage they did, and how many casualties of their people were avoided. From September 1879 to October 1880, Victorio was engaged in five campaigns against the United States, and in three against the Mexicans, where he defeated and outmaneuvered his enemies (Watt 2011b).

After winning many battles against the U.S. military, on May 23, 1880, Victorio had a skirmish with U.S. troops, losing warriors and horses. He retreated to Mexico, where he was ambushed on October 14, 1880, by Colonel Joaquin Terrazas at Tres Castillos. All of the warriors were killed. According to Apache tradition, Victorio killed himself with his own knife rather than be killed by the enemy. Not only did male warriors fight at this last battle, females died fighting as well. Some Apaches escaped, but nearly 100 women and children were taken captive as slaves.

Lozen was not by Victorio’s side, as she had stayed behind to assist in a pregnancy. After the delivery of the child, Lozen killed a longhorn, stole a horse, and avoided the enemy as she tried to help the woman and infant return to the Mescalero reservation. At her arrival, she was told of her brother’s death and went south to rejoin Nana, who had survived as well. It is said that many believed that if Lozen had been by Victorio’s side, such ambush would have never happened. Lozen was gifted with the ability to find the enemy. She would summon the power through a ritual in which she extended her arms with her palms up, and prayed. It is said that a tingle in her palms indicated the direction of the enemy, or if that her hands turned purple, it signaled that the enemy was extremely near. Lozen and Nana later joined Juh, Naiche, and Geronimo in the last Apache fights.

When Victorio was killed, Nana was away on a mission to acquire ammunition. Upon his return, he found survivors and headed for safety to the Sierra Madre. When they returned to bury the dead, he found Victorio with the knife in his chest. Nana then prepared to go on a revenge expedition. Nana was one of the oldest warriors, and although he was in his seventies, he was respected as one of the fiercest warriors. He was half-blind and walked with a limp, but he was reputed as a great rider and fighter. He had been born under Spanish rule and fought under Mangas Coloradas.

A campaign of revenge began weeks after the death of Victorio. Small parties of warriors trailed and killed some of Colonel Terraza’s men. Nana’s warriors continued to strike as they moved from Mexico to New Mexico and back to Mexico, killing at a mining town and later near Fort Cummings. As the band kept moving, they found more survivors who joined the group. From July to August 1881, Nana took revenge on the people of New Mexico and Mexico. Nana’s raid covered over 1,000 miles. It was considered legendary, and with a small band of 15 to 40 warriors, Nana killed, wounded, and stole. Nana’s band fought soldiers and civilians and managed to win most of their battles, while avoiding capture by 1,000 soldiers in pursuit (Thrapp 1967). Eventually, they settled briefly in the Sierra Madre Mountains.

DOCUMENT EXCERPTS

General George R. Crook (1830–1890), who was considered one of the leading fighters against the Native Americans, wrote in admiration of his enemy. General Crook recognized that

“In fighting them we must of necessity be the pursuers, and unless we can surprise them by sudden and unexpected attack, the advantage is all in their favor. In Indian combats it must be remembered that you rarely see an Indian; you see the puff of smoke and hear the whiz of his bullets, but the Indian is thoroughly hidden in the rocks, and even his exact hiding place can only be conjecture.”

Source: Crook, George R. “The Apache Problem.” Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States. Vol. 7, p. 262. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1886.

Ambushes were a technique used to cause the maximum damage to the enemy while avoiding losses. Decoys were subtle and used to lure the enemy. Ambushes were used “to drive the enemy off and take plunder, to end a pursuit, or to kill as many of their opponents as possible” (Watt 2011b, 476). Preparing an ambush required strategizing. A location had to be selected that would allow the Apaches to retreat unharmed. Ambushes targeted the horses and the mules first and then the soldiers. When ambushes were successful, the Apaches proceeded to attack and kill off their enemy, but if at any point they felt that they might have major losses, the Apaches were always ready to retreat. Direct attacks were also done, but careful consideration was always taken in weighing the likelihood of success.

In 1886, General Crook wrote “The Apache Problem” and noted that the Apache warriors were formidable foes. He understood that the Apaches were fighting for their land. Because of their great skills, he also knew that the only way to find and capture the Apaches would be to employ their same tactics, which led to the employment of Apache scouts.

These Indians recognized at once the inferiority of their bows and arrows to the firearms of the European colonist, and for this reason, if no other, as a rule were almost uniformly friendly in their first encounters with the white settlers, and it was not until they became convinced that their country would soon be overrun by the new race that they ventured, as a last resort, to engage in hostilities …

“We have before us the tiger of the human species. To no tribe in American can these remarks apply with more force than to the Apaches of Arizona … It has taken the expenditure of countless treasure and blood to demonstrated that these naked Indians were the most thoroughly individualized soldiers on the globe; that each was an army in himself, waiting for order from no superiors—thoroughly confident in his own judgement and never at a loss to know when to attack or when to retreat.…

Source: Crook, George R. “The Apache Problem.” Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States. Vol. 7, pp. 257, 269. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1886.

Further Reading

Aleshire, Peter. Cochise: The Life and Times of the Great Apache Chief. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2001.

Ball, Eve. An Apache Odyssey: Indeh. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

Barrett, S. M. Geronimo’s Story of His Life. Manchester, UK: Corner House Publishers, 1980.

Betzinez, Jason. I Fought with Geronimo. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Company, 1959.

Colwell-Chanthaponh, Chip. “Western Apache Oral Histories and Traditions of the Camp Grant Massacre.” American Indian Quarterly 27(3&4) 2003, 639–666.

Cozzens, P., ed. Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890: The Struggle for Apacheria. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001.

Guidotti-Hernandez. “Embodied Forms of State Domination: Gender and the Camp Grant Massacre.” Social Text 104 28(3) 2010, 91–117.

Lekson, Stephen H. Nana’s Raid: Apache Warfare in Southern New Mexico. El Paso: Texas Western Press, 1987.

Lockwood, Frank C. The Apache Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1938.

Opler, Morris E. An Apache Life-Way: The Economic, Social & Religious Institutions of the Chiricahua Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1941.

Robinson, Sherry. I Fought a Good Fight: A History of the Lipan Apaches. Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2013.

Shapard, Bud. Chief Loco: Apache Peacemaker. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Sonnichsen, C.L., ed. Geronimo and the End of the Apache Wars. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

Stout, Joseph A. Apache Lightning: The Last Great Battles of the Ojo Calientes. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Thrapp, Dan L. The Conquest of Apacheria. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967.

Watt, Robert N. “Apaches Without and Enemies Within: The U.S. Army in New Mexico, 1879–1881.” War in History 18(2) 2011a, 148–183.

Watt, Robert N. “Victorio’s Military and Political Leadership of the Warm Springs Apaches.” War in History 18(4) 2011b, 457–494.

Angelique EagleWoman (Wambdi A. WasteWin)

Chronology

1803 |

France sells its colonizer rights to mid-North America to the United States in a transaction referred to as the “Louisiana Purchase,” which includes the homelands of the Dakota peoples. |

|

1805 |

Lieutenant Zebulon Pike is commissioned to negotiate the first U.S. treaty with the Dakota leaders to secure a nine-mile-square tract to build the U.S. Fort Snelling; first treaty has an open-ended payment term that the U.S. Senate fills in to set its purchase price. |

|

1825 |

Council for the Treaty of Prairie du Chien called by U.S. representatives to set up territorial boundaries between multiple tribal nations to begin individual treaties for land cessions. |

|

1830 |

The Treaty of 1830 involves a land cession for a tract of land 20 miles wide from three Dakota bands: Mdewakanton, Wahpekute and Wahpeton. |

|

1836 |

The Treaty of 1836 extends the boundary line of the state of Missouri into Dakota lands and involves a further land cession with the Wahpekute, Sisseton, and Upper Mdewakanton. |

|

The Treaty of 1837 contains the land purchase by the United States of all Mdewakanton land east of the Mississippi River and includes the islands in the river. |

||

1849 |

Minnesota Territory established with a plan to remove the Dakota peoples from their lands under governor and ex officio superintendent of Indian Affairs Alexander Ramsey. White settlers are constantly encroaching upon Dakota lands. |

|

1851 |

At the council called by the United States for the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux, alcohol was served, and following the treaty-signing, newspapers report the sale of 21 million acres of the world’s finest land. Tribal leaders are directed to sign their “x” marks on another paper and later discover that the document was for creditors’ claims to be deducted from the land purchase amount. |

|

1853 |

The 1851 Treaty is amended by the U.S. Senate, striking out the provisions for permanent reservations on either side of the Minnesota River, without notification to the Dakota leadership. |

|

1858 |

During a trip to Washington, D.C., Dakota leaders are coerced in an all-night meeting to sign another set of treaties relinquishing the northern lands along the Minnesota River and dividing the southern lands into allotments, or lose all of their lands. |

|

June 1862 |

Treaty food rations are late in arriving, while the Dakota and Nakota peoples suffer starvation conditions. Local traders refused to extend credit for those gathered, numbering over 5,000. |

|

August 17–18, 1862 |

Certain groups of Dakota leadership decide to go to war to reclaim their homelands after the deceptive practices of the U.S. government, local traders, and encroaching white settlers. |

|

September 24, 1862 |

Chief Taoyateduta moves all captives to Camp Release and departed with a number of families to the westward plains for buffalo hunting, ending the war. |

|

November 1862 |

At the conclusion of a military criminal panel put together by General Henry Sibley, condemned and imprisoned Dakota families are marched to Fort Snelling. A total of 303 men are listed for execution by General Sibley. |

|

December 6, 1862 |

U.S. President Lincoln affirms the execution of 39 Dakota men by public hanging (one would be exonerated prior to the hanging), and the authorization is received by General Sibley. |

|

Largest mass execution in the history of the United States when 38 Dakota men are publicly hanged on a specially built scaffold in Mankato, Minnesota. |

||

1863 |

Two federal laws are enacted: one to nullify all treaties with the Dakota, and the second to permanently remove the Dakota from Minnesota and seize their lands. Dakota peoples are scattered to the four directions, including relocating to Canada. |

Dakota Leaders and the U.S. Government, 1850s

As Dakota leaders interacted with the U.S. government, they were frequently deceived into relinquishing their homelands and resources for survival. Through a series of coercive treaties in the 1850s, the United States pushed the Dakota peoples into smaller portions of their homelands that would not sustain the tribal communities. With the largest land swindle of 21 million acres in 1851, the Dakota leaders attempted to continue to provide for their communities and convince U.S. leaders of the hardship imposed on them.

By the early 1860s, white settlers in Minnesota encroached on much of the Dakota homelands and called for the annihilation of the peoples. Against this backdrop in 1862, the treaty-guaranteed food rations were late, and the Dakota peoples were suffering starvation conditions. After the denial of food from storehouses and the inhumanity of the local whites towards their condition, the Dakota leaders decided to go to war. The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 took place for approximately a month, from mid-August to mid-September. Following the end of the War, the majority of those who fought left the area. Those who remained were condemned as prisoners of war. Thirty-eight men were condemned to death by hanging by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. On December 26, 1862, the largest mass execution in the history of the United States took place in Mankato, Minnesota.

The U.S. Plan for Land Dispossession of the Dakota Peoples

The Dakota peoples consisting of the Mdewakantons, Sissetons, Wahpekutes, and Wahpetons lived in a vast area of abundant stewarded lands when Europeans entered mid-North America. As the United States was formed and sought to expand from the eastern seaboard, U.S. officials followed a campaign of land acquisition from the Dakota peoples. From 1805 to 1858, a series of U.S. treaties, written in the English language using legal terms and improperly interpreted to gain consent, were entered into with the Dakota leadership.

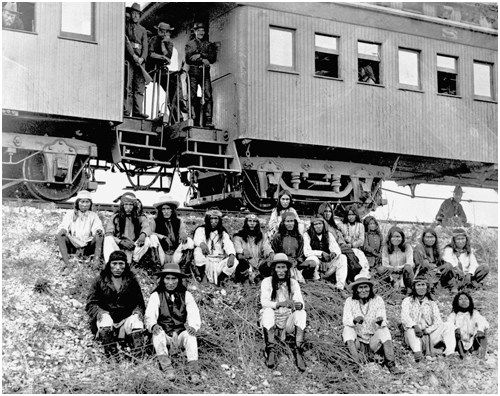

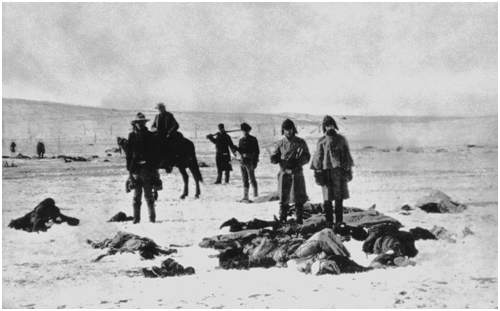

Execution of Dakota Indians in Mankato, Minnesota, on December 26, 1862. This hanging of 38 Dakota remains the largest mass execution in U.S. history. (Photo12/UIG via Getty Images)

On April 30, 1803, France sold its interest in mid-North America to the United States. The claimed interest by France included the homelands of the Dakota peoples. Soon afterward, the United States authorized Lieutenant Zebulon Pike to negotiate a treaty in the Dakota territory to construct a fort. The U.S. treaty document had an open-ended payment term for the purchase of a nine-mile-square land area. When the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty three years later, the payment term was filled in as “two thousand dollars, or deliver the value thereof in such goods and merchandise as they shall choose” (Treaty with the Sioux, Sept. 23, 1805). From this first negotiation for a land purchase, the uneven bargaining of the U.S. government was apparent.

By 1825, U.S. expansion was planned through acquisition of the fertile meadows, forests, and lakes home to many tribal nations in mid-North America. In order to acquire these lands, a plan was followed, beginning with calling a council of tribal leadership for the Prairie du Chien treaty. Representatives of the Dakota, Chippewa, Menominee, Winnebago, Iowa, Sac and Fox, Potawatomi, and Ottawa tribes gathered to meet with U.S. Colonel William Clark and Territorial Governor Lewis Cass. The purpose of the treaty was to designate boundary lines between the tribal territories so that the U.S. officials would enter into individual tribal negotiations for land cessions. Some leaders resisted the boundary lines and tried to explain the shared resources and use by the tribal peoples to Clark and Cass. The leaders were given alcohol, and eventually the treaty council was concluded with the boundaries set.

In the treaties of 1836 and 1837, the Dakota leadership allowed the expansion of the Missouri boundary northward and allowed for U.S. use of the lands east of the Mississippi River and the islands within it. Each successive treaty moved the Dakota people further west within their homelands. The final and largest land purchase was coerced from the Dakota leadership in 1851.

With the treaty of 1851, the United States claimed to acquire 21 million acres from the Dakotas, the largest land purchase by the U.S. government.

Deteriorating Conditions for the Dakota Peoples in the 1850s and 1860s

Through these dealings with the U.S. government, the Dakota peoples became forced to live on smaller and smaller reserved lands in their original homelands. In 1849, the Minnesota Territory was established, and white settlers began to move into the Dakota homelands. By the 1850s, the U.S. plan to dispossess tribal nations of their lands was being routinely implemented. A treaty council was called on July 18, 1851, with the Dakota peoples. In describing what took place, historians have noted the deceptive practices used to garner the “x” marks of the leaders.

All the standard techniques were employed by the commissioners. The carrot and the stick—and at least once the mailed fist—were alternately displayed, as the occasion seemed to demand. If the Indians asked for time to consider the terms offered them, they were chided for behaving like women and children rather than men. If they asked shrewd, businesslike questions, the commissioners uttered cries of injured innocence: surely the Indians did not think the Great Father would deceive them! If they wanted certain provisions changed, they were told it was too late; the treaty had already been written down. (Meyer, 77–78)

Although tribal leaders requested no changes be made upon ratification, the U.S. Senate struck out the provisions of the treaty reserving homelands on the north and south sides of the Minnesota River. The new term added that a home would be designated at some future time. The 1851 Treaty payment terms were misrepresented to the Dakota leaders and the actual land price set by the United States amounted to six cents per acre.

Further, Governor Ramsey tricked the Dakota leaders into signing credit receipts from local traders for the land payments to be first applied to those statements.

Each Indian, as he stepped away from the treaty table, was pulled to a barrel nearby and made to sign a document prepared by the traders. By its terms the signatories to the treaty acknowledged their debts to the traders and half-breeds and pledged themselves, as the representatives of their respective bands, to pay those obligations. No schedule of the sums owed was attached to the document, but after the ceremony was over the traders got together and scaled down their claims (originally estimated at $431,735.78) to the round sum of $210,000; the half-breeds were to get $40,000. (Meyer, 80)

U.S. President Thomas Jefferson masterminded the plan to allow private and public trading posts to hold tribal peoples in debtor/creditor relationships to force land sales. Tribal peoples were known for their integrity in seeking to fulfill and pay off proper debts. By keeping them in a state of indebtedness, the private and U.S. traders worked with the U.S. government to force land sales. In a private letter to Indiana Territorial Governor William Henry Harrison in 1803, Jefferson set forth his plan.

To promote this disposition to exchange lands, which they have to spare and we want, for necessaries, which we have to spare and they want, we shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop off by a cession of lands. (Prucha, 22)

Through this type of trickery at the highest levels of the U.S. government, Dakota leadership was purposefully deceived in their dealings with the U.S. Indian agents, the federally licensed Indian traders, and the entire U.S. leadership.

As white settlers swarmed into the Dakota lands, the hunting and harvesting of traditional resources became difficult to maintain. The Dakota peoples became dependent on the traders’ supplies and the treaty rations. In 1858, a group of the Dakota leaders traveled to Washington, D.C., to seek justice on the treaty payments, stop the encroachment on their homelands, and have their complaints addressed. Instead, federal officials in D.C. imposed two more treaties that purported to purchase the northern lands along the Minnesota River and divide the southern lands into plots. At an all-night session, the tribal leaders were coerced by Commissioner of Indian Affairs Charles Mix to place “x” marks on these treaties or lose all of their lands entirely.

From the 1850s to the 1860s, Indian agents used treaty rations and other items to favor those families adopting Christianity and farming. For those continuing the traditional cultural lifestyle, food was withheld, leading to greater debts with the local traders. Whites entering lands reserved for the Dakota peoples were not repelled by the U.S. officials. These conditions would lead to the final push by the Dakota to reclaim their homelands and way of life along the Minnesota River.

The Dakota Decision to Go to War

In July 1862, the Dakota peoples and the related Yankton/Nakota peoples gathered to receive treaty food rations at the Indian agency. The rations were late, and the people were starving. With storehouses of food locked and surrounded by soldiers, the Indian agent Tom Galbraith meted out the bare minimum to keep the Dakotas and Yanktons alive for another three weeks. The local traders also cut off all credit accounts.

By August 15, Itancan Taoyateduta (Chief His Red Nation, also known as Chief Little Crow) requested provisions to the lower agency and a timeline on when the food would be delivered. He made the statement that “when men are hungry, they help themselves” referring to the food owed under the treaties and the locked storehouses (Meyer, 114). Agent Galbraith asked the local traders to reply. Andrew Myrick gave a reply that was translated by a local reverend as “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass” (Folwell, 232). Those who had gathered left angry at the trader’s words.

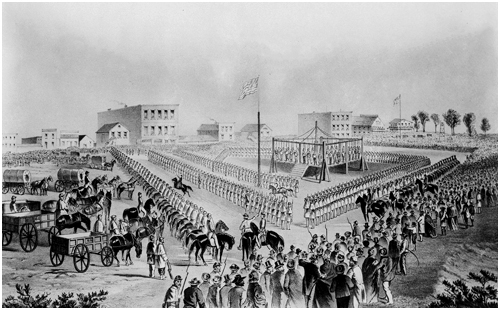

Mdewakanton Santee Dakota chief Little Crow, who had previously been hospitable and accommodating toward white settlers, led an uprising in Minnesota in 1862. Conflict had arisen when food promised in treaties was being withheld in the warehouses of traders, while many Dakota were dying from starvation. (Library of Congress)

Two days later, a few young men fought over stealing eggs from a farmhouse. When the white settlers inside came out, a confrontation ensued, leading to the young men killing three white men and two white women. When the young men returned to their families and informed them of what had taken place, the older men fully expected the U.S. military to retaliate by opening fire on all of the Dakota peoples. Under this pressure, the decision was made to go to war to clear the whites from the homeland, open the storehouses to feed the people, and defend the Dakota families. In reviewing this series of events, one historian has maintained that white settlers and officials had a motive to provoke an Indian war as a pretext for seizing all of the reserved Dakota lands (Meyer, 124).

The decision to go to war was not unanimous, with many adopting the white ways and cautioning against it. From oral history, Itancan Wambdi Tanka’s (Chief Big Eagle’s) statements have been preserved, detailing the human rights violations by the whites towards the Dakota peoples as a reason for the declaration of war.

Then many of the white men often abused the Indians and treated them unkindly. Perhaps they had excuse, but the Indians did not think so. Many of the whites always seemed to say by their manner when they saw an Indian, “I am much better than you,” and the Indians did not like this. There was excuse for this, but the Dakotas did not believe there were better men in the world than they. Then some of the white men abused the Indian women in a certain way and disgraced them, and surely there was no excuse for that. (Anderson & Woolworth, 1988)

Against this backdrop of racism, the Dakota leadership debated and finally some settled on war. Itancan Taoyateduta first counseled restraint but accepted his role to lead and the consensus among his men to fight.

The U.S.-Dakota War spanned mid-August to mid-September. Whites panicked, and newspapers added to the frenzy. The trader Andrew Myrick was one of the first shot, and his mouth was stuffed with grass (Folwell, 233). Some of the key events included a charge upon Fort Ridgely on August 20, with as many as 800 Dakota men participating. In describing the military maneuvers of the Dakota, the Dakota style of warfare was directed at competing against the opposing men and taking captives of civilians, women, and children.

While the main body of the Sioux warriors was alternatively attacking Fort Ridgely and New Ulm, smaller parties were carrying out raids all over southwestern Minnesota. Among the places where white casualties were heavy were Milford Township in Brown County, Lake Shetek in Murray County, and portions of Kandiyohi County. In most cases the men were killed, the women and children taken prisoner and held until the final defeat of the Indians at Wood Lake. (Meyer, 120)

On September 12, 1862, Itancan Taoyateduta sent word to General Henry Sibley that he wanted to make peace and end the war. The general sent back a harsh reply that peace was not an option. During the war, all sides lost lives with a final battle at Wood Lake. At this battle, an ambush was planned on the white soldiers encamped in the area. Before the ambush was set, a group of soldiers who were going to dig potatoes disrupted the plan, and the battle ensued with the Dakota scrambling for position. After the battle, with many Dakota killed, white soldiers mutilated and scalped the bodies of the dead (Anderson, 159).

Following that battle, the Dakota leaders set up a temporary camp named Camp Release and brought in all of the captives. Itancan Taoyateduta brought in his people on September 24 and then traveled westward for buffalo hunting, thus ending the war. General Sibley took three days to march to the camp, which was within a day’s journey for his troops. When he arrived, he immediately announced that all of those present were prisoners of war and released the 107 whites and 162 mixed-blood captives (Brown, 58). Most of the Dakota peoples at Camp Release had sheltered or helped the whites during the war and did not expect to be condemned as prisoners of war.

Aftermath and Military Criminal Panels to Execute Dakota Men

General Sibley took matters into his own hands and used his military officers as mock judges on three-man panels to prosecute and determine the fate of each Dakota man at Camp Release. As other units brought in Native men to the camp, they were also tried by the military panels for criminal acts. Under threat of execution, certain English-speaking men of mixed Dakota and white heritage were used as witnesses against those on trial. These sham trials led to the conviction of 303 Dakota men condemned to death, and 16 others sentenced to extended prison terms (Brown, 59). The manner directed to the Dakota peoples following the surrender at Camp Release has been referred to as “one of the blackest pages in the history of white injustice to the Indian” (Meyer, 123–24). Sibley was denied the authority to immediately execute those he had condemned and was ordered to march the Dakota men, women, and children to Fort Snelling.

From November 7 to 13, the men, women, and children were marched in the Minnesota winter with white mobs attacking them outside of towns. “While they were being escorted past New Ulm, a mob of citizens that included women attempted ‘private revenge’ on the prisoners with pitchforks, scalding water, and hurled stones. Fifteen prisoners were injured, one with a broken jaw, before the soldiers could march them beyond the town” (Brown, 60). Upon arrival at Fort Snelling, the Dakota men were separated and placed in Camp Lincoln while U.S. President Lincoln reviewed the list of those to be executed. He authorized Sibley to execute 39 of the 303, though one was later exonerated.

Sidebar 1: Minnesota Settlers’ Racism against the Dakota Peoples

The racial animus aimed at Dakota peoples by Minnesota settlers was evident in the newspaper accounts from the late 1850s and following the 1862 War. In an 1857 Red Wing Minnesota newspaper, an item was printed that stated, “We have plenty of young men who would like no better fun than a good Indian hunt” (Meyer, 101–2). Special agent Kintzing Prichette, from Washington, reported that there appeared to be “one sentiment to inspire almost the entire population, and this was, the total annihilation of the Indian race within their borders” in Minnesota (Meyer, 101–2).

Following the 1862 War, the newspapers published commentary calling for extermination of the Dakota peoples. The public sentiment was reported as bent on vengeance and calling for “Death to the murderous Sioux … Let vengeance swift, sure, complete and unsparing teach the red-skinned demons the power of the white man” (Folwell, 190). The portrayal of Native Peoples in this dehumanized characterization has been adopted in team mascots throughout contemporary Minnesota and the surrounding region in elementary through post-secondary educational institutions.

On December 26, 1862, the largest mass execution in the history of the United States took place in Mankato, Minnesota. A specially built scaffold was used for all 38 men to stand on with nooses around their necks and hoods on their heads. Many sang Dakota hymns and traditional songs as they waited for death. A large white crowd witnessed the executions. The Dakota men sentenced to prison were transported to Davenport, Iowa. Thirteen hundred Dakotas were held captive at Fort Snelling, with 300 dying that winter. White missionaries consistently sought to proselytize among those held prisoner at the fort.

In February of 1863, two federal laws were enacted to nullify the treaties with the Dakota and to remove them from the Minnesota area. Other features of the second federal law included provisions for the U.S. president to establish a reservation outside the borders of any state and have it divided for farming into 80-acre allotments, selling off of all reserved lands of the Dakota in the Minnesota area, and to use Dakota proceeds to buy farming implements with the express limitation that no direct funds would be delivered to the people themselves. Swept up in the anti-Indian sentiment, the Winnebago tribe was also removed by federal law from the Minnesota area.

In the aftermath, the Dakota peoples scattered to the four directions. Some remained in Minnesota, and others fled to Canada, and home reservations were eventually established in what became Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

Commemorating the Forced March of the Dakota Peoples

Since 2002, Dakota peoples have walked together on commemorative marches to Mankato, Minnesota, every two years in November to honor the memories of those who were held as prisoners of war and those who were executed. Chris Mato Nunpa recounted that “[t]he marchers who participated in the Commemorative March 140 years after the 1862 event came from South Dakota, North Dakota, from reserves in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, as well as from Nebraska and Minnesota” (Wilson, 67). Every two years another march is organized for healing and remembering the difficult time the Dakota peoples endured.

A participant in the 2004 march, Mary Beth Faimon, explained how the marches have been conducted. “The Dakota Commemorative Marches are grassroots organized events, initiated and planned by Dakota women who are descendants of those on the 1862 forced march … Decolonizing efforts were made throughout the march. For example, at each mile marker along the route, a flagged stake was placed in the ground bearing the name of an ancestor who was on the original march. Tobacco and prayers were offered. An eagle feather staff was carried high, leading walkers to the next highway mile marker for 150 miles. Each day began and ended with a ceremony” (Wilson 88).

In January 2012, a film was released, entitled Dakota 38. The film documents a spiritual journey of 38 Dakota riders on horseback during the winter of 2008 from Lower Brule, South Dakota, to Mankato, Minnesota, arriving on December 26, 2008. The riders endured blizzard conditions over the 330-mile journey, which has been planned on an annual basis since 2008.

Biography

Itancan Taoyateduta (Chief His Red Nation, referred to as Chief Little Crow by whites) was born in 1810 and was killed on July 3, 1863, in Minnesota. When he was born, his mother, Minio Kadawin (Woman Planting in Water), a chief’s daughter from the Wahpeton, would sit with him in silence in nature to allow him to enjoy solitude (Eastman 44). He was a fourth-generation leader on his father’s side. His grandfather’s name, Cetanwakuwa (Charging Hawk), had been mistranslated by the whites to mean “Crow” which is why they called him “Little Crow” as a misnomer. His father, Wakinyantanka (Big Thunder), was a great leader and died by an accidental gunshot wound. As he grew, he demonstrated great acts of bravery such as saving a friend who had fallen through ice, by tying a line and pulling them both to safety.

When he became the leader of the Eastern Dakota, he was known as a great hunter, had gained a reputation facing danger delivering messages to other Dakota leaders, and tried to compromise between the Indian ways and the white ways. A great orator and man of judgment, he led during some of the most difficult times facing the Dakota peoples. He was a leading spokesman for the treaty councils in 1851 and 1858. Throughout the negotiations, he stated his distrust that the agreements would be carried out. At the signing of the 1858 treaty, he reportedly stated: “That is the way you all do. You use very good language, but we never receive half what is promised or which we ought to get” (Diedrich 2014).

Throughout the U.S.-Dakota War, Chief His Red Nation masterminded strategic attacks on local forts and continued to fight with honor. For example, he refused to attack General Sibley’s army at Wood Lake during the night and waited for daybreak in an honorable way. He ended the Dakota War by releasing captives and those who had chosen to remain in the area at Camp Release. Returning to the plains, he sought assistance from the British at Fort Garry, but they refused to assist the Dakota peoples against the United States. Returning to Minnesota in July 1863, he was shot while gathering berries with one of his sons. His skull, arm bones, and scalp were displayed at the Minnesota state capitol until finally buried in 1971 at Flandreau, South Dakota.

DOCUMENT EXCERPTS

The largest public execution in the history of the United States was the hanging of the 38 Dakotas in Mankato in 1862. The Ikce Wicasta: The Common People Journal Winter 1999 volume was dedicated to “the 38 Dakotas hung at Mankato, Minnesota in 1862” and listed their names as follows:

Minnesota Adjutant General Oscar Malmros issued General Order No. 41, setting a bounty on the scalps of any Dakota killed.

General Headquarters, State of Minnesota

Adjutant General’s Office

St. Paul, Minnesota, July 4th, 1863

The continued outrages of the Sioux Indians in the Big Woods, and in the rear of the U.S. outposts for the border defence, render it imperatively necessary that extraordinary measures should be adopted for the more complete protection of our frontier and the extirpation of the savage fiends who commit these outrages.

It is therefore ordered that a corps of volunteer scouts be organized immediately for sixty days, unless sooner discharged, to scour the Big Woods from Sauk Centre to the Northern boundary line of Sibley county.

The corps shall be composed of one Captain and from forty to sixty men, who shall be divided into squads of not less than five men under the immediate command of their own chosen leader, subject to the order of the Captain of Scouts.

Persons desiring to enlist in this corps will report immediately, by letter to this office.

As soon as one squad of not less than five men, has been formed, they will at once enter upon active service, without waiting for a mustering officer.

Each squad will be mustered in for pay as of the date when they entered into active service as aforesaid.

The leader of each squad will report frequently his movements and place where letters may reach him, to this office.

Men volunteering for this service will have to arm, equip and subsist themselves at their own expense, and will be paid for their services at the rate of one dollar and fifty cents per day. A compensation of twenty-five dollars will also be given to any body for each scalp of a male Sioux delivered to this office.

None but experienced hunters, scouts or marksmen will be accepted. Every organized squad, and the Captain of Scouts, as soon as the company is fully organized, will communicate and act in concert with the U.S. forces stationed on our frontier.

By order of the Commander-in-Chief

Oscar Malmros, Adjutant General.

Source: Annual Report of the Adjutant General. Minnesota Adjutant General’s Office, 1858, 132–33.

This order was later adjusted by General Order No. 44:

General Headquarters, State of Minnesota

Adjutant General’s Office

St. Paul, Minnesota, July 20th, 1863

General Orders No. 41 … is hereby modified so as to read as follows:

…

A reward of seventy-five dollars will likewise be paid to any person who is not mustered into the service of the State or of the United States for every hostile Sioux warrior killed by such person within the State, upon the production of the proper proofs at this office.

All persons proposing to act as independent scouts for the above reward of seventy-five dollars, and without any other compensation, will report their names and places of residence to this office.

By order of the Commander-in-Chief

Oscar Malmros, Adjutant General.

Source: Annual Report of the Adjutant General. Minnesota Adjutant General’s Office, 1858, 135–36.

A local newspaper responded:

Barbarism.—… Adjutant General Malmros, has issued an order offering a bounty of twenty five dollars for the scalp of any male Sioux. We look upon this proposition as a relic of the dark ages, barbarous, inhumane and unbecoming the enlightened age in which we live.… We have no objection to urge against killing the red devils who are guilty, but let the fair name of our State never be disgraced by paying a bounty to murder innocent children, even if they are Indians. God has made them what they are, and we have no right to take their lives unless forfeited by some act of their own. We hope the new Commander-in-Chief will at once revoke this disgraceful and objectionable portion of Order No. 41.

Source: Chatfield Democrat, July 18, 1863.

See also: The Sioux Bill of 1889

Further Reading

Anderson, Gary C. Little Crow: Spokesman for the Sioux. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1986.

Anderson, Gary C. and Alan R. Woolworth, eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1988.

Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970.

Diedrich, Mark F. 2014. “Little Crow,” American National Biography Online, April 2014. http://www.anb.org/articles/20/20-00593.html

Eastman, Charles A. (Ohiyesa). Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains. Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1918.

Folwell, William W. A History of Minnesota, Vol. II. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1961.

Meyer, Roy W. History of the Santee Sioux: United States Indian Policy on Trial. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1967.

Wilson, Waziyatawin Angela, ed. In the Footsteps of Our Ancestors: The Dakota Commemorative Marches of the 21st Century. St. Paul: Living Justice Press, 2006.

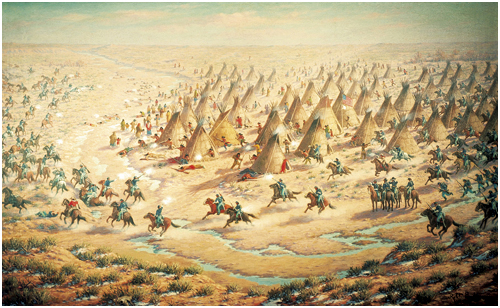

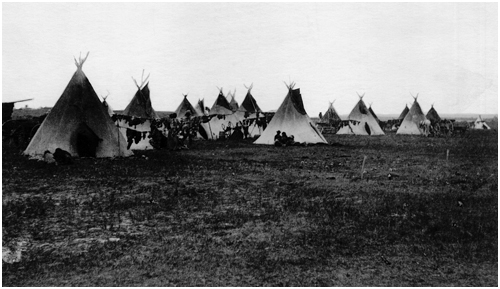

The Sand Creek Massacre, November 29, 1864

Jonathan Byrn

Chronology

1858 |

Gold is discovered in Colorado, and Denver is established. |

|

1859 |

The Pike’s Peak gold rush commences. |

|

February 28, 1861 |

Colorado Territory is established. |

|

September 1861 |

The Treaty of Fort Wise is signed by the Cheyenne and Arapaho, reducing the hunting territory established in the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851) and creating a reservation between the Sand Creek and Arkansas River. |

|

May 16, 1864 |

Chief Lean Bear rides out to greet a column of soldiers approaching his camp with Star, another Cheyenne, displaying his peace medal and document presented to him by President Lincoln in 1863 to demonstrate his peaceful intent. The troop commander orders his men to kill them. Cheyenne Chief White Antelope later states that this murder ignited the later hostilities that year. |

|

June 11, 1864 |

The Hungate family, white settlers, are found murdered on their ranch southeast of Denver. The murders are blamed on Arapaho war parties, and many rural families move closer to towns, inciting further hostilities toward Indians in the region. |

|

June 27, 1864 |

Evans’s “Proclamation to Friendly Indians of the Plains.” Colorado Territory Governor John Evans warns peaceful Indians not to associate with those causing hostilities and to identify themselves and gather at places like Fort Lyon, where provisions and safety would be provided. |

|

Evans’s telegraph to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Evans sends an emergency telegraph to the army, claiming the Plains tribes were banding together for war against the whites. “It will be the largest Indian war this country ever had, extending from Texas to the British lines, involving nearly all the wild tribes of the Plains. Please bring all the force of your department to bear in favor of speedy re-enforcement of our troops, and get me authority to raise a regiment of 100-days’ mounted men” (Hoig 1961, 67). |

||

August 11, 1864 |

Evans’s proclamation to Colorado citizens. Evans encourages and authorizes Coloradans “to kill and destroy, as enemies of the country, wherever they may be found, all such hostile Indians,” promising compensation and loot for those who participate (Hoig 1961, 68). |

|

August 13, 1864 |

Evans’s proclamation authorizing a 100-days regiment. Evans and Col. John Chivington begin recruiting unemployed men in Denver and nearby mining towns after receiving funding authorization from Washington. |

|

September 4, 1864 |

Chief Ochinee brings Black Kettle letter to Fort Lyon. The Cheyenne chief, his wife, and their escort, Eagle Head, run into a patrol, who disobey orders to kill Indians on sight, escorting the three to Fort Lyon to speak with Major Edward “Ned” Wynkoop, convincing him to meet with tribal leaders at Smoky Hill River. Wynkoop then agrees to arrange a meeting with Colonel Chivington and Evans. |

|

September 28, 1864 |