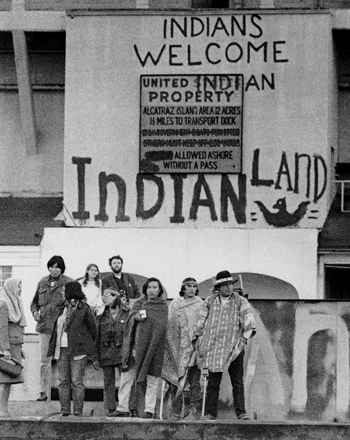

From the Great Depression to Alcatraz, 1929–1969

National Congress of American Indians, 1944

Katie Kirakosian

Chronology

Introduction

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) is an intertribal, activist, non-profit organization that seeks to provide a space for its members to voice their concerns about, and offer solutions to, the complex issues in Indian country and, more broadly, faced by American Indians and Alaska Natives. Although not the first organization of its kind, today the NCAI is the “oldest, largest, and most representative American Indian and Alaska Native organization” (National Congress of American Indians). Since its founding in 1944, the NCAI’s mission has been focused on protecting treaties and sovereign rights, ensuring continued access to traditional culture for future generations, historicizing tribal governments and their right to nation-to-nation relations with other governments, and improving the overall quality of life for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Five key policy areas help structure the NCAI’s efforts: Community & Culture; Economic Development & Commerce; Education, Health, & Human Services; Land & Natural Resources; and Tribal Governance (National Congress of American Indians).

The 1940s

Cornell (1988) paints the 1940s and the decades that followed as a time when “Indians not only have demanded a voice in decision making but they have appropriated such a voice for themselves” (Cornell 1988, 5). The founding of the NCAI came at a crucial time because many politicians and Americans wanted full integration of American Indians and Alaska Natives. For example, in 1943 Congressman Karl Mundt questioned the need for an Indian Bureau at all, arguing that was “not more necessary than a bureau to handle problems for Italians, French, Irish, Negroes, or any other racial group” (Mundt 1943 as cited in Bernstein 1999, 114). Here the argument for American Indian integration into dominant society fueled others who felt tribal sovereignty was unnecessary and even contradictory.

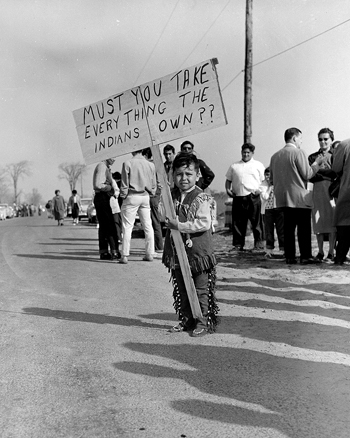

Representatives of various tribes attending an organizational meeting of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), 1944. Their founding conference occurred in Denver, Colorado, due to its central location to the majority of reservations. It stood against federal termination and relocation policies that sought to end the legal status of all tribes. The NCAI remains active on various issues and is the oldest American Indian national organization in the United States. (nsf/Alamy Stock Photo)

Despite varied dissent, on November 15, 1944, nearly 80 delegates representing 50 tribes met at the Metropolitan Hotel in Denver, Colorado (National Congress of American Indians). This was an unprecedented gathering of intertribal leaders and included a diverse group of tribal councilors, religious leaders, and members of the BIA. By the time the group dispersed on November 18, 1944, the NCAI was officially formed.

Sidebar 1: The Road to the NCAI’s Founding

The founding of the NCAI must be contextualized within a wave of pan-Indianism or supratribalism that emerged in the 20th century, in “response to [the United States government’s] termination and assimilation policies” (National Congress of American Indians). In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt tapped John Collier to serve as the commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a position that he held until 1945. Collier was vehemently opposed to forced assimilation and set four new objectives for the BIA, which were “rebuilding Indian tribal societies, enlarging and rehabilitating Indian landholdings, fostering Indian self-government, and preserving and promoting Indian culture” (Blackman 2013, 54). He argued against boarding schools that took children away from their families and communities, which was also a concern noted in the Meriam Report. Instead, he pushed for local reservation-based schools that fostered traditional teachings and cultural pride. During his tenure as Indian Commissioner, Collier worked to ensure that the BIA’s monopoly on “Indian lives and affairs by the BIA was curbed, at least for a while, and the powers of the agents were checked; cultural preservation was encouraged and the suppression of indigenous religion reduced” (Cornell 1988, 93).

One key piece of legislation during Collier’s tenure that helped pave the way for the NCAI was the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. This act set a new course for American Indians and Alaska Natives (Cornell 1988), and the initiative was meant to facilitate Collier’s “dream of reviving Indian tribes and customs, thus restoring to Indians a sense of pride in their communities and themselves” (Taylor 1980, 17). Specifically, through this act, Collier and his staff worked to combat many of the devastating effects of colonization while also promoting self-governance, economic stability, and tribal rights. The spirit of the IRA led many to call Collier a communist, while he repeatedly had to dodge congressional attacks that relentlessly pushed for termination and assimilation following the IRA’s passage (Wilkinson 2006). None of this deterred Collier and his determination to see his vision realized, although he is still seen of as a controversial figure in Indian country today.

The founding of the NCAI was “a turning point in Indian affairs as Indians emerged as skilled political organizers and lobbyists for their interests at the national level” (Bernstein 1999, 112). Things like the Indian Reorganization Act “convinced a new generation of Indian that they could determine their own destiny” (Bernstein 1999, 112). While the NCAI changed the political landscape, concerns over tribal and BIA factionalism were a real threat during these early years.

Sidebar 2: A List of All NCAI Presidents and Executive Directors

Term |

President |

|

1944–1952 |

Napoleon B. Johnson (Cherokee) |

|

1953–1959 |

Joseph R. Garry (Coeur D’Alene) |

|

1960–1964 |

Walter Wetzel (Blackfeet) |

|

1965–1966 |

Clarence Wesley (San Carlos Apache) |

|

1967–1968 |

Wendell Chino (Mecalero Apache) |

|

1969–1970 |

Earl Old Person (Blackfeet) |

|

1971–1972 |

Leon F. Cook (Colville) |

|

1973–1976 |

Mel Tonasket (Colville) |

|

1977–1978 |

Veronica L. Murdock (Mohave) |

|

1979–1980 |

Edward Driving Hawk (Sioux) |

|

1981–1984 |

Joseph DeLaCruz (Quinault) |

|

1985–1987 |

Reuben A. Snake, Jr. (Winnebago) |

|

1988–1989 |

John Gonzales (San Ildefonso Pueblo) |

|

1990–1991 |

Wayne L. Ducheneaux (Cheyenne River Sioux) |

|

1992–1995 |

gaiashkibos (Lac Courte Oreilles) |

|

1996–1999 |

W. Ron Allen (Jamestown S’Klallam) |

|

2000–2001 |

Susan Masten (Yurok) |

|

2002–2005 |

Tex Hall (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara) |

|

2006–2009 |

Joe A. Garcia (Ohkay Owingeh) |

|

2010–2013 |

Jefferson Keel (Chickasaw Nation) |

|

2014–Present |

Brian Cladoosby (Swinomish) |

|

Term |

Executive Director |

|

1944–1948 |

Ruth Muskrat Bronson (Cherokee) |

|

1949 |

Louis R. Bruce (Mohawk/Sioux) Edward Rogers (Chippewa) |

|

1950 |

John C. Rainer (Taos Pueblo) |

|

1951 |

Ruth Muskrat Bronson (Cherokee) |

|

1952 |

Frank George (Colville) |

|

1953–1959 |

Helen Peterson (Oglala Sioux) |

|

1960–1963 |

Robert Burnett (Rosebud Sioux) |

|

1964–1967 |

Vine Deloria, Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux) |

|

1968 |

John Belindo (Navajo/Kiowa) |

|

1969 |

Bruce Wilkie (Makah) |

|

1970 |

Franklin Ducheneaux (Cheyenne River Sioux) |

|

1971 |

Leo W. Vocu (Oglala Sioux) |

|

1972–1977 |

Charles Trimble (Oglala Sioux) |

|

1978 |

Andrew E. Ebona (Tlingit) |

|

1979–1982 |

Ronald Andrade (Luiseno-Dieguneo) |

|

1983 |

Silas Whitman (Nez Perce) |

|

1984–1989 |

Susan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne) |

|

1990–1991 |

A. Gay Klingman (Cheyenne River Sioux) |

|

1992 |

Michael J. Anderson (Creek/Choctaw) |

|

1993 |

Rachel A. Joseph (Shoshone/Paiute/Mono) |

|

1994–2000 |

JoAnn K. Chase (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara) |

|

2001–2014 |

Jacqueline Johnson Pata (Tlingit) |

|

The NCAI accomplished a great deal by the close of the decade, such as establishing the Indian Claims Commission (ICC), working against termination legislation, and seeking an end to voting discrimination in states like Arizona and New Mexico (Cowger 2001). The NCAI also directly aided tribes under threat, like the Navajo and Hopi tribes in the late 1940s. To ensure solidarity over these and other issues, the theme of the 1948 convention was “One for All, All for One, United We Endure.” A document entitled “Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Mutual Assistance” was meant to “erase past tribal differences and to unite the tribes in a common future” and was signed by all NCAI member tribes (Cowger 2001). Little did the NCAI know that they would need to be more united then ever on issues soon to come (Cowger 2001,74).

The 1950s

Although this decade was difficult for the NCAI, it did start with a decided victory. In 1950, the NCAI worked to add an anti-reservation clause in the Alaska Statehood bill, which allowed Alaska Natives to form reservations. However, a dire situation took hold of Indian country in this decade because of the efforts of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1950 to 1953, Dillon S. Myer, who relocated and “integrated” thousands of American Indian adults from reservations to nearby cities (Fixico 2000). Myer had experience with relocations, as he was in charge of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which oversaw the forced removal and relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II. In 1952, the federal government started the Urban Indian Relocation Program, which pushed for the assimilation of American Indians into dominant society. This initiative was continued by the next commissioner as well, Glenn Emmons (1953–1960). In 1953, Congress introduced House Concurrence Resolution 108 (HCR 108), which required that “the end of reservations and federal services and protections be completed ‘as rapidly as possible’ ” (Wilkinson 2006, 57). Coupled with this was Public Law 280, which gave states criminal jurisdiction in over half of the Indian reservations (Champagne and Goldberg 2012). The 1953 conference became a critical meeting for the NCAI. Yellowtail spoke at the convention, referring to termination as “a conspiracy.” He was clear that “The job of the Indians everywhere is to arrest and defeat these bills.… There is no time for bickering among tribal leaders; it is instead time for the united action against the common enemy” (Yellowtail as cited by Hoxie 2012). Also during this conference, the membership elected Joseph Garry (Coeur d’Alene) as the group’s third president. A master organizer and politician at heart, he worked tirelessly visiting numerous tribes across the country to explain what termination would mean for them (Fahey 2012). His efforts were also supported by the NCAI’s Executive Director, Helen Peterson (Oglala Sioux), who served alongside Garry. Together they worked to thwart federal assimilation and termination efforts and to ensure that self-determination was just that. Three things supported their vision for self-determination: honoring treaty rights, self-governance, and economic self-sufficiency (Tomblin 2009, 226).

In February 1954, Garry called an emergency conference in Washington, D.C., which was covered by thousands of media outlets (National Congress of American Indians). By the close of the conference, the group had proposed a Point IX program that argued for long-term self-sufficiency and had also approved a “Declaration of Indian Rights.” Although the Point IX program was never implemented, it proved that American Indians could advocate for themselves. Another victory later that year included voting down Public Law 280. Here Yellowtail’s words from the year before had come to fruition as the NCAI membership worked together, more united then ever before, to speak out against termination and relocation.

In 1958, the NCAI put together a 14-member delegation to visit Puerto Rico and learn more about “Operation Bootstrap” (Goldstein 2012). More specifically, they wanted to see how Puerto Rico had successfully positioned itself as “foreign in a domestic sense” while also ensuring “political autonomy” (Goldstein 2012,85). Upon their return, they helped put together a proposal entitled “Operation Bootstrap for the American Indian,” which resulted in congressional hearings starting in 1960 (U.S. Government Printing Office 1960). While this did not become law, the push for termination quieted somewhat.

The 1960s

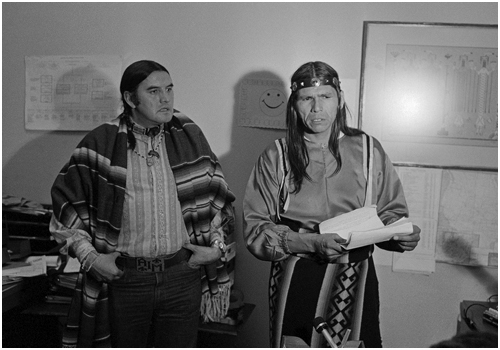

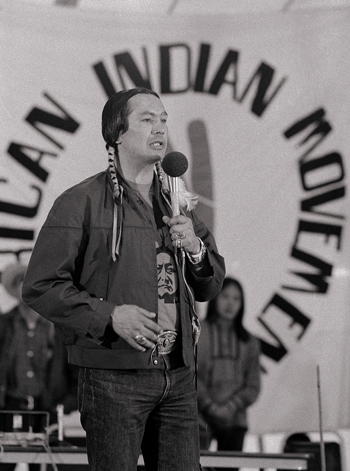

According to Cowger (2001), the NCAI has always been seen as a moderate group. This was in extreme contrast to more militant groups like the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) and the American Indian Movement (AIM), which were both founded in the 1960s and saw the NCAI as a “paper tiger.” While the moderate road forged by the NCAI may have led to its survival, it likely also led to some growing pains during this decade.

The NCAI worked off of the momentum of its earlier “Operation Bootstrap” initiative to write the “Declaration of Indian Purpose: The Voice of the American Indian” in 1961, which focused on the importance of tribal sovereignty and preserving American Indian and Alaska Native identity. Many elements of this declaration were later implemented in President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” (National Congress of American Indians). Later in his administration, Johnson began the Office for Economic Opportunity (OEO), which was often at odds with the BIA, which they saw as “anti-Indian.” OEO’s efforts were focused on “not only economic development but expertise development,” which led to numerous reservations starting programs that were not dependent on the BIA (Tomblin 2009, 229).

This decade saw troubles in Indian country as well. As the executive director of the NCAI from 1964 to 1967, Deloria is credited with returning “the organization back to financial and organizational stability” (Cowger 2001, 4). Unfortunately, these were difficult years internally for the NCAI for other reasons, with issues still boiling over in regard to termination as well as the complex identities and histories of various reservation and urban American Indian groups, who had strong communities in Los Angeles, Oakland, Chicago, and Minneapolis, for example (Deloria, Jr. 2014). In 1964, the NCAI and the Affiliated tribes of Northwest Indians revoked membership from the Menominee Indians of Wisconsin over their internal push for termination, which the NCAI vehemently opposed. By 1968, however, tribal leadership had changed, and termination was off the table, leading the NCAI to reverse several membership decisions (Wilkinson 2006, 182).

As mentioned, early in the decade another Indian organization, the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), was formed and had a rather different vision for American Indians’ future as well as methods to attain this vision. Many leaders in the NIYC had been born on reservations and represented a new group of Indian activists who were tired of the tactics of earlier generations. The NIYC supported various initiatives and protests in the decade, like the 1964 fish-ins in Washington State. The NCAI focused its efforts in different ways. For example, the first Miss NCAI Scholarship Pageant was held in 1968, which was intended to empower and celebrate young Native women for their many gifts. Also in 1968, the Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA) was passed and was aimed at ensuring civil rights in Indian country. When applying the ICRA, the courts have ensured that tribal customs and traditions are considered and that federal courts are only involved after tribal processes and courts have been involved.

The 1970s

During this time, the NCAI continued its moderate path. This lies in contrast to three groups founded in the previous decade: the American Indian Movement (AIM), the Indians of All Tribes (IOAT), and the United Native Americans (UNA). These groups were more militant in focus and took part in numerous occupations throughout the country to bring attention to their cause. Instead, the NCAI focused its efforts on working within Washington to push for change. According to Charles Trimble (Oglala Sioux), who served as executive director from 1972 until 1977, the NCAI almost collapsed in 1970 due to financial mismanagement the year before.

This decade bore witness to many positive changes for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Although such policies had waned by this time, in 1970, President Nixon officially ended the federal government’s push for tribal termination. Instead, he endorsed self-determination, which was a huge victory supported by the NCAI. In part, Nixon and his staff argued, “We have concluded that the Indians will get better programs and that public monies will be more effectively expended if the people who are most affected by these programs are responsible for operating them” (Nixon 1970).

Congress passed several key pieces of legislation with the support of groups like the NCAI, including the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975), the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (1976), and finally, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and the Indian Child Welfare Act (1978). Ironically, this also came at a time when there was a “white backlash” from 1976 to 1977 that “saw the rise of state-level anti-tribal groups,” which sent over a dozen pieces of legislation to Congress “calling for reversing Indian hunting and fishing rights court victories, terminating federal-tribal relations, and abrogating the Indian treaties” (Trimble 2009). The NCAI was able to push through, with the help of other groups like the American Indian Law Center, NARF, AIM, and the NTCA under the name “United Effort Trust.”

The early 1980s were difficult years in terms of securing strong NCAI leadership. By 1984, Susan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne) became the executive director. Being well connected in Washington and around the country, Harjo ensured that the NCAI had a strong presence on Capitol Hill. She helped push for the Tribal Government Tax Status Act of 1983, various programs aimed at economic development, and the establishment of the National Museum of the American Indian.

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan issued a statement on Indian Policy, which pushed for local control of tribal affairs. Reagan was clear that he saw the federal government’s role with Indian nations as a government-to-government relationship. Partly in response to this, the NCAI published an extensive report that same year, entitled Tribal Governments at the Crossroads of History. Environmental protection, especially the impacts of nuclear waste, was an increasing concern that led to the 1988 publication of Environmental Protection in Indian Country: A Handbook for Tribal Leaders and Resource Managers. As with each earlier decade, the NCAI continued its work with other groups to ensure the passage of important legislation. The most important piece of legislation to come out of this was the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988, which set the state for economic security for federally recognized tribal nations.

The 1990s

This decade began with the passage of two key pieces of legislation supported by many groups, including the NCAI. These were the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and the Indian Arts and Crafts Act. Since that time, the NCAI has been critical of the actual achievements of both laws by the federal government. In 1990, the Supreme Court also heard Duro v. Reina and ruled that Indian tribes could not prosecute nonmember Indians on their lands. In other words, Indian tribes only have jurisdiction over their own tribal members. This came as a blow to American Indians and Alaska Natives, but it was soon corrected with the Congressional “Duro fix” the following year, which determined that due to the powers of self-government, Indian tribes indeed have jurisdiction over all Indians (both members and non-members). In 1994, President Bill Clinton issued a memorandum to all executive departments, explaining the government’s responsibility to consult with tribal nations. In 1996, Clinton also issued Executive Order 13007, which was aimed at protecting and preserving Indian religious practices and sacred sites located on federal lands. Finally, in 1996, the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act was passed, which sought to address the housing crisis in Indian country. This bill has been amended and reauthorized numerous times since its initial passage. In 1997, the NCAI started the Youth Commission, which brings together youth aged 16 to 23 to consider issues facing their communities, and unique ways to met those challenges.

The New Millennium

The new millennium has seen many new NCAI initiatives and programs. In 2003, the Policy Research Center was formed, which is a “think tank” focused on unique issues faced by tribal communities across the United States. In 2009, the Embassy of tribal nations was opened in Washington, D.C. According to then NCAI president Jefferson Keel, “For the first time since settlement, tribal nations will have a permanent home in Washington, D.C., where they can more effectively assert their sovereign status and facilitate a much stronger nation-to-nation relationship with the federal government” (National Congress of American Indians). Since 2010, the NCAI has worked with other groups to support the passage of the Tribal Law & Order Act (2010), the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (2010), and the Violence Against Women Act (2013) with added provisions to ensure that tribal governments protect Native women.

The NCAI has also focused on larger global issues as well as making connections to other indigenous populations in the new millennium. For example, the NCAI partnered with the Native American Relief Fund (NARF), which now represents the NCAI on matters related to climate change. In 2009, the two groups proposed Tribal Principles for Climate Change legislation, which brought attention to the fact that American Indians and Alaska Natives are incredibly vulnerable when it comes to climate change and should, therefore, be closely consulted about climate change legislation. In 2010, President Barack Obama endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This was a symbolic victory for indigenous groups, as the United States had initially voted against the declaration in 2007 (along with Australia, Canada, and New Zealand). In 2011, the NCAI was invited to give the keynote address at the National Congress of Australia’s First People, and they held the first-ever joint meeting with Canada’s Assembly of First Nations (National Congress of American Indians).

The NCAI has focused its energies on many new initiatives to involve Native youth. Successful programs include the NCAI’s National Native Youth Cabinet (NNYC), which was established to support the growth of tomorrow’s tribal leaders (aged 16 to 25). In 2012, it also formed an online community for Native youth called NDN Spark. The NCAI also offers internships and fellowship, including two specifically focused on tribal policy and governance and health disparities.

In his 2015 State of Indian Nations address, current NCAI president Brian Cladoosby (Swinomish) urged the NCAI to consider its part in a larger story “of pride and resilience book-ended by self-determination on either end” (Cladoosby 2015). Cladoosby is optimistic that today, American Indians and Alaska Natives are living in a time “that our ancestors prayed for” (Cladoosby 2015). If it were not for the determination of groups like the NCAI, the future of American Indians and Alaska Natives would be less certain. Over more than seven decades, the NCAI has served as a voice, although never the voice, for Indian country. The NCAI is keenly aware that its members come from an incredibly diverse group of nations, and it sees the value in bringing various perspectives together to consider issues that affect every corner of Indian country.

Biographies of Notable Figures

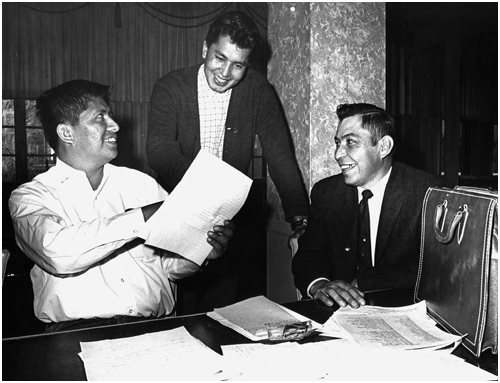

Joseph Garry (Coeur d’Alene) and Helen Peterson (Oglala Sioux)

One notable duo who can be credited with saving the NCAI as well as countless Indian nations are Joseph Garry (Coeur d’Alene) and Helen Peterson (Oglala Sioux), by working together to push against federal assimilation and termination efforts during their tenure. Garry was elected NCAI President in 1953, with Peterson named executive director that same year. They served together through the end of that tumultuous decade. As leaders and organizers, they were able to bring together diverse Native and non-Native groups around issues of mutual concern.

Garry was born in 1910 and grew up on the Coeur d’Alene reservation in Idaho. He served in the U.S. Marines in World War II and the Korean War and was elected to his tribal council. He was also the president of the Affiliated tribes of the Northwest Indians. Garry set his sights on becoming NCAI’s President in 1953 and, according to Peterson, “ran a very dignified and sophisticated campaign to become president” (Peterson as cited in Fahey 2012, 30). Garry ensured the support of many in that year’s elections, especially when Clarence Wesley officially nominated him. Peterson was born in 1915 on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. She grew up in Nebraska, in the house of her Cheyenne grandmother, who was Black Kettle’s niece (Varnell and Hanson 1999). She went to the NCAI after working in Denver’s Department of Health and Welfare, getting minority voters registered.

Upon being elected, Garry and Peterson inherited a troubling situation. They were faced with the impending demise of all tribal nations through a series of congressional bills, and the NCAI was nearly bankrupt. There were also a series of congressional committees at that time, focused on the effectiveness of tribal governance and law enforcement on reservations and possible land taxation. Congress also wanted to allow the sale of liquor and firearms to American Indians, explaining that their efforts were aimed at equal rights for all. Garry and Peterson, however, sensed ulterior motives (Fahey 2012). Together they traveled the country asking for donations and soliciting new members to help fund the NCAI’s much-needed presence in Washington, D.C. During that time, Arrow was of little help, although established as a fundraising arm for the NCAI. Garry and Peterson were unimpressed with Arrow’s efforts and urged the closure of its New York office. They also worked tirelessly against McCarthyism during that time, as the NCAI was at times labeled a Communist group.

In early 1954, Garry and Peterson called an emergency conference focused on these issues. In his press release, Garry explained that the meeting was to “develop constructive programs which will serve Indian values and serve the best interests of the nation by protecting its national honor” (Rosier, 175). Amazingly, they were able to organize this meeting in less than three weeks, given the urgency of the situation. In a letter from Peterson to Garry, Peterson was clear that “The convention this year may very well be the most critical for Indians in this century … There can be no doubt that the accumulated bills in the last session were the gravest threat to Indian property and rights since the Allotment Act of 1887 … To consolidate the gains of this year and to plan for the future may never be more important than now” (Peterson as cited in Fahey 2012). Garry and Peterson were careful to enlist the support of other groups as well, including the Association of American Indian Affairs. At the time, this meeting was the largest inter-tribal demonstration, with representatives from 42 tribes. The conference also included individuals from 19 non-Indian organizations who were equally concerned with the current situation (Fahey 2012). Garry and Peterson also worked to show that Indians could solve their own problems, as outlined by Congress.

By 1955, the threat of termination had lessened, as supportive Democrats gained control of Congress, with increased power in 1957 as well. The challenges experiences during these years helped strengthen the NCAI and also made American Indian and Alaska Natives more politically savvy. In 1956, the NCAI helped support a program called “Register, Inform Yourself and Vote.” Politicians took note of these important changes during this time as well and recognized Native Americans and Alaska Natives as viable constituents with unique needs and challenges (Cowger 2001). Peterson collaborated with McNickle to start a summer workshop series for Native American students at Colorado College, which began in 1956 and ended in 1970. These workshops set the stage for countless collegiate ethnic studies departments across the country. Peterson was the NCAI’s first female director, and when she left office, she had been the longest-serving executive director as well.

By the end of Garry’s and Peterson’s tenure, the NCAI “had become a sophisticated organization formulating policies reflecting the opinions and views of Indian Country, as well as organizing lobbying skills that battered the US government’s termination policy, protected Indian land rights and promoted Indian civil rights” (Ryser 2012, 58). Together, they are credited with getting the NCAI back on solid ground during one of the organization’s most challenging times.

Vine Deloria, Jr.

Another important figure in the NCAI in the 1960s was Vine Deloria, Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux). Born in 1933 and raised partly on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, he came of age during a crucial time in American Indian history. Deloria, Jr. came from a prominent family, with his great-grandfather a noted medicine man, his grandfather an Episcopal priest, his aunt an anthropologist and linguist, and his father also an Episcopal priest. After serving in the U.S. Marines, he earned a B.A from Iowa State University and a B.D. in theology from Augustana Lutheran Seminary in 1963. Shortly thereafter, he worked for a time in Denver in the United Scholarship Service, which helped American Indians get scholarships to attend college.

By the time he ran for executive director in 1964, Deloria, Jr. was utterly discouraged with the state of Indian activism. The NCAI had shrunk significantly and only represented 19 tribes, although, by the end of his tenure, membership had swelled to 156 tribes (Lawrence 2010). The group was also yet again in financial straights, which he corrected during his time as executive director. In that role, he often testified before Congress on civil rights and other issues related to American Indians. For example, he testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary on a bill that later became the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Deloria and Wildcat 2006). In that testimony, he argued that tribes would need funding to train Indian trial judges. His suggestion is credited with leading to the establishment of the National American Indian Court Judges Association in 1969 (Deloria, Jr. and Wildcat 2006).

Deloria, Jr. found that American Indians themselves, who were very focused on internal squabbles, stymied many of his efforts. There were also many other American Indian groups forming at the time, and they had visions different from the more moderate NCAI, which required his attention as well. Deloria, Jr. was always careful to downplay the many occupations of key locations across the country by more militant American Indian groups as chance happenings, for fear that it would undue his and the NCAI’s hard work in Washington, D.C. In the end, his vision for activism was much different from that of many at the time. It was more in line with the NCAI’s in that he saw the need for change from within the federal government. He wrote about his NCAI experiences in part in Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (Deloria 1969).

Concerned about the general public’s understanding of Native American history, Deloria, Jr. and the NCAI worked during this period to ensure that American Indians and Alaska Natives were fairly portrayed and equally represented in the media. In 1967, for example, the NCAI learned that ABC was airing a television series on Custer. The group protested the series because of its unbalanced portrayal of Custer, and they sued for equal airtime. Although the general public was largely unaware of the struggles occurring behind the scenes over this series, the NCAI was able to have the series cancelled after only nine episodes when FCC hearings became imminent (Deloria, Jr. 2014).

His time in the NCAI had a profound effect on Deloria, Jr. Most directly, his time as NCAI’s executive director increased his national stature. As he recalls, he began writing during that time because “I wanted to give good briefings before Congress. I got to love old documents and learning how to root around in them” (Deloria, Jr. as cited in Lawrence 2010). Ultimately, Deloria, Jr.’s belief that there needed to be more trained Indian lawyers led to his resignation in 1967 and his enrollment in the University of Colorado Law School (Lawrence 2010). Deloria, Jr. still consulted with the NCAI during that time and also published many short columns in the Sentinel, the NCAI’s quarterly newsletter (Lawrence 2010). Deloria, Jr. was a prolific writer, publishing a book every few years—20 books throughout his life, many of which were bestsellers.

Deloria, Jr. worked to support fishing rights, starting in the 1960s. For most of the 1970s, he served as the chairman of the Institute for the Development of Indian Law and on the board for the National Museum of the American Indian. He also came to the assistance of the Iroquois Six Nations in their wampum belt recovery. In 1974, he was called as a witness for the defense in the Wounded Knee Trials, where he collaborated with attorney John Thorne. In the 1990s, he continued his activism and spoke out against federal acknowledgment. While testifying before Congress, he argued, “It is certainly unjust to require Indian nations to perform documentary acrobatics for a slothful bureaucracy.” For three decades (until his retirement in 2000), he taught at various universities, and he helped to establish a master’s program in American Indian studies at the University of Arizona.

Further Reading

Bernstein, Alison R. American Indians and World War II: Toward a New Era in Indian Affairs. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999.

Champagne, Duane and Carole E. Goldberg. Captured Justice: Native Nations and Public Law 280. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2012.

Cladoosby, Brian. State of Indian Nations address. http://www.ncai.org/about-ncai/state-of-indian-nations (accessed September 24, 2015).

Cornell, Stephen. The Return of the Native: American Indian Political Resurgence. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Cowger, Thomas W. The National Congress of American Indians: The Founding Years. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

Deloria, Vine, Jr. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. Norman: The University of Oklahoma Press, 2014 [1969].

Deloria, Vine, Jr. and Daniel R. Wildcat. Destroying Dogma: Vine Deloria, Jr. and His Influence on American Society. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 2006.

Fahey, John. Saving the Reservation: Joe Garry and the Battle to Be Indian. Seattle: The University of Washington Press, 2012.

Fixico, Donald Lee. The Urban Indian Experience in America. Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, 2000.

Goldstein, Alyosha. Poverty in Common: The Politics of Community Acton During the American Century. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2012.

Hoxie, Frederick E. This Indian Country: American Indian Political Activists and the Place They Made. New York: The Penguin Press. 2012.

Lawrence, Michael Anthony. Radicals in their Own Time: Four Hundred Years of Struggle for Liberty and Equal Justice in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010.

National Congress of American Indians. www.ncai.org (accessed September 24, 2015).

Nixon, Richard. President Nixon, Special Message on Indian Affairs, July 8, 1970. http://www.ncai.org/resources/consultations/nixon-special-message-on-indian-affairs (accessed on September 25, 2015).

Ryser, Rudolph C. Indigenous Nations and Modern States: The Political Emergence of Nations Challenging State Power. New York: Routledge. 2012.

Tomblin, David C. Managing Boundaries, Healing the Homeland: Ecological Restoration and the Revitalization of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, 1933–2000. Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 2009.

Truman, Harry S. 233. Veto of Bill Establishing a Program in Aid of the Navajo and Hopi Indians. http://trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/viewpapers.php?pid=1251 (accessed September 24, 2015).

Varnell, Jeanne and M.L. Hanson. Women of Consequence: The Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame. Boulder: Big Earth Publishing. 1999.

Wilkinson, Charles F. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2006.

The Anti-Discrimination Act, Alaska Natives, 1945

Caskey Russell

Chronology

Alaska Natives and the Fight against Discrimination

The gallant fight that Alaska Natives are waging today for the defense of their rights is a fight against racist principles that threaten all Americans. For the rights of each of us in a democracy can be no stronger that the rights of our weakest minority.

Felix Cohen, 1948

In Juneau, Alaska, on February 8, 1945, the Alaskan Territorial Legislature was in session debating a bill designed to put an end to legalized racial discrimination and segregation in Alaska’s public buildings and privately owned businesses. Sitting in the packed public gallery amid a host of Alaskan Natives during the 1945 legislative session were the architects of the anti-discrimination bill: Elizabeth and Roy Peratrovich, both Tlingit Indians. Roy and Elizabeth had introduced a similar anti-discrimination bill before the legislature two years earlier, in 1943, but it had been defeated, in part because of a clause that would have desegregated public schools. That clause had been removed when the bill came up again before the legislature in 1945. Desegregating public schools would have to wait.

Alaskan legislative procedure at the time allowed for the public to address the legislature during open debate, so both Roy and Elizabeth were able to speak directly to any legislators who opposed their bill. The bill passed the House by a large margin, but was held up in the Senate, culminating in a two-hour debate, where racist senators lashed out against the idea of legally prohibiting segregation. Senator Allen Shattuck represented the feelings of many non-Indians when he told Roy during the debate, “Mr. Peratrovich, as I mentioned to you before, this bill will aggravate, rather than allay, the little feeling that now exists. Our Native cultures have ten centuries of white civilization to encompass in a few decades” (Dauenhauer 1994, 537).

Roy replied, “Only an Indian can know how it feels to be discriminated against. Either you are for discrimination or you are against it, accordingly as you vote on this bill” (Dauenhauer 1994, 537). This was not the first time Senator Shattuck and Roy Peratrovich disputed the myth of white superiority. Several years earlier, in response to comments made by Shattuck regarding Indians’ low level of civilization, Roy had written, “I am wondering just what they [white people] call civilization. Looking over the court record in Alaska, one wonders if the white man is really civilized” (Dauenhauer 1994, 534).

Elizabeth Peratrovich’s debate with Senator Shattuck during the 1945 session is best remembered by history. Elizabeth sat calmly knitting during much of the debate. When her turn to speak came, Elizabeth stood before the all-white male Senate and ripped apart the pro-segregation senators. The following excerpt, taken from the Senate Record, is a small part of that confrontation:

Senator Shattuck: This legislation is wrong. Rather than being brought together, the races should be kept further apart. Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites, with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind us?

Elizabeth Peratrovich: I would not have expected that I, who am barely out of savagery, would have to remind the gentlemen with 5,000 years of recorded history behind them of our Bill of Rights.…

Senator Shattuck: Will this law eliminate discrimination?

Elizabeth Peratrovich: Do your laws against larceny, rape and murder prevent those crimes? No law will eliminate crimes, but at least you, as legislators, can assert to the world that you recognize the evil of the present situation and speak of your intent to help us overcome discrimination.… This super race attitude is wrong and forces our fine Native People to be associated with less than desirable circumstances. (Dauenhauer 1994, 537–38)

After her speech, the gallery exploded with applause. The anti-discrimination bill passed the Senate, eleven to five. The bill became law on February 16, 1945. A famous picture from that day shows a smiling Elizabeth standing next to the Alaskan Territorial Governor Ernest Gruening as he signed the bill into law. Later that evening, Elizabeth and Roy danced the night away at the Baranof Hotel in downtown Juneau. The “No Natives” sign that once adorned the hotel had been taken down. February 16 is now an official state holiday in Alaska in honor of Elizabeth and her civil rights work—in particular, to the memory of her speech in support of her anti-discrimination bill.

To understand how this bill became law nearly 20 years before the civil rights movements of the 1960s and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it is helpful to examine the background of the Peratroviches, the Native political organizations to which they belonged, and the situation that Alaskan Natives found themselves in at the turn of the 20th century. Alaska in the 1800s and early 1900s was seen by non-Natives as a frontier of potential wealth. In American mythology, Alaska symbolized the Horatio Alger narrative writ large onto a new “frontier”: poor, white, American men could travel to the gold fields of the Alaskan interior or to the Alaskan shores and forests, which teemed with fish, furs, and timber, and with enough tenacity, masculinity, and a bit of luck they could become wealthy. In reality, the profits from the vast resources of Alaska, taken from lands, forests, and seas stolen from Alaskan Natives, usually ended up in the coffers of wealthy businessmen, mine owners, cannery owners, and lumber barons who often resided outside Alaska.

In both the mythology and the reality, Alaskan Native communities mattered little. For the Native People who had lived in Alaska from time immemorial, the late 1800s up through 1950s was a prolonged period of colonization, cultural loss and destruction, racism and segregation, and sustained erosion of tribal sovereignty. Jim Crow policies similar to those in the American South were common across Alaska during this era. If one were to walk through the major towns of early 20-century Alaska, one would find signs on restaurants, theaters, businesses, and public buildings that read, “All White Help,” “No Dogs, No Natives,” and “No Natives Allowed.” Alaskan Native families, to this day, share stories of family members of that era being forced out of businesses and buildings, or being refused housing, jobs, or school admission because they were Indian. “We don’t want you stinking siwashes in here,” one Alaskan drugstore owner yelled at the author’s great grandmother when she and young her daughter tried to enter his store in Ketchikan. At the time, the term “siwash, which was derived from the word for savage in Chinook Jargon, was the most opprobrious slur a non-Native could use against an Alaskan Native. Alaskan Native Elders still associate that word with virulent racism.

Alaskan Natives had no legal redress in the courts for such discrimination. The legal status of Alaskan Natives was tenuous. When Russia sold Alaska to the Unites States, Alaskan Natives were not considered American citizens. Moreover, in Alaska until the 1930s, “… with the exception of the Tsimshians on Annette Island, Congress had not formally recognized any tribes” (Metcalfe 2014, 1). Yet, Alaskan Natives were subject to state taxation (including the five-dollar yearly public school tax, even though they were banned from attending public schools), state laws, and, subsequently, the Alaskan criminal justice system. Robbed of their lands and resources, and lacking the legal standing needed for redress within the U.S. legal system, early Alaskan Native leaders focused their efforts on gaining citizenship and voting rights, which would provide the legal footing needed to fight for civil and political rights. Citizenship was conferred to all American Indians in 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, which also secured voting rights for American Indians. Shortly thereafter, in 1925, the Alaskan Territorial Legislature, in a blatant attempt to prevent Alaskan Natives from voting, passed a law making literacy in English a perquisite. This was Alaskan Native reality that Elizabeth and Roy were born into during the early 20th century.

After graduating from Chemawa, an Indian boarding school in Oregon, Roy attended Western College of Education (now Western Washington University). Elizabeth was attending the same college. Though Roy and Elizabeth had known each other before college, their relationship blossomed at Western, and the two married in Bellingham, Washington, in December 1931. Roy and Elizabeth eventually moved to the Tlingit village of Klawock on the west coast of the Prince of Wales Island in the early 1930s. Klawock was a natural choice: Roy had been born in Klawock, and Elizabeth had lived there for a short period of time in her youth. In Klawock, they involved themselves in local politics—Roy served as mayor of the village for four terms—and in the two main political organizations for Alaskan Natives that, at that time, were dedicated to political and social change in Alaska: the Alaskan Native Brotherhood (ANB) and the Alaskan Native Sisterhood (ANS).

When it was founded in 1912, the ANB encouraged Natives to become educated and assimilated, and to adopt Western customs in order that they might become active members of the larger Alaskan and American community. By the time the Peratroviches became leaders of the ANB in 1940, however, the ANB had become an activist organization involved in protecting Native lands, ending segregation, and pursuing legal action against the U.S. government. The ANB also became a watchdog group that kept an eye on the political machinations of non-Natives. According to Richard and Nora Dauenhauer:

When Indian school children were denied admission to the public school in Juneau, the ANB sued the district and forced the school to integrate. The ANB and ANS monitored federal legislation, assuring that Natives and all minority groups in the territory were treated equitably. (Daunehauer 1994, 532)

The ANB was also instrumental in electing the first Native Alaskan Territorial Legislator, William Paul, in 1923. Paul is one of the most important figures in 20th century Tlingit history. He attended Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, graduated from Whitworth College in Washington State, and worked on a law degree through a correspondence/extension program at LaSalle University. By 1920, he had passed the Alaskan bar exam and become the first Native lawyer in Alaska and shortly thereafter was elected to the Alaskan Territorial Legislature. Paul had joined the ANB soon after its founding. He would become a major figure in the ANB throughout the early 20th century. Paul served as Grand President of the ANB five times between1920 and 1940. As a legislator and attorney familiar with the legal aspects of politics, his influence was immense. Paul must be given credit for turning the ANB into a politically active organization whose concern was protection of Alaskan Native rights and resources. He refocused the ANB toward issues of citizenship, property rights, ending school segregation, and redress for stolen tribal land and resources.

Sidebar 1: The Alaskan Native Brotherhood (ANB): From Assimilation to Activism

The ANB was founded in 1912 by a group of Russian Orthodox and Presbyterian Alaskan Natives who had been educated in western religious institutions. The ANB was derivative of certain groups, or “societies,” founded by Russian Orthodox priests in Alaska, all of whom were assimilationist in nature. Donald Mitchell, in his book Sold American, credits the initial idea of a Native political organization to Joseph McAfee, secretary of the Presbyterian Board of Missions, who suggested the idea after listening to Native grievances regarding turn-of-the-century U.S. policy in Alaska (194). As originally founded, the ANB had overtly assimilationist goals and attempted to promote “civilization” among Alaskan Natives. Two of the ANB’s tenets were an English-only requirement for membership, and a belief in Christian theology. The First Article of ANB’s constitution states, “The purpose of this organization shall be to assist and encourage the Native in his advancement from his Native state to his place among the cultivated races of the world” (Mitchell 1997, 274).

A basis in Christian theology was due to the fact that the ANB founders were all products of Native education programs based on religious models of education (such as missions or boarding schools). Regarding the English-only aims of the ANB, it has been pointed out that, at the founding of the ANB, the Tlingit language was in no apparent danger of being lost. Tlingit was still the first language for most tribal members. The Tlingit people themselves, however, were of a generation that remembered the danger of simply being Indian. At such times, survival is more important than any language concern.

Under the leadership of William Paul, beginning in the 1920s, the ANB became a political organization aimed at promoting voting rights, citizenship for Alaskan Natives, and desegregating public schools. With the leadership of William Paul, and later the Peratroviches (Roy, Elizabeth, and Frank), the ANB turned into an activist organization to attack segregation and discrimination.

In 1920, Paul pushed the ANB to adopt a resolution against school segregation in Alaskan public schools (Dauenhauer 1994, 508). Paul was also a strong advocate for Native suffrage. The Native voting presence in Alaska was considerable—roughly one-quarter of the population of Alaska—and elections could be lost if prospective candidates failed to court the Native vote. If one wanted the Native vote, one had to court the ANB, or more precisely, the leaders of the ANB who could rally Native People behind a candidate. Paul created an ingenious voting device to help Alaskan Natives who could not read English: cardboard templates that could be placed atop voting ballot sheets. Holes were cut out of the cardboard templates that allowed Natives to make a mark next to the ANB-supported candidate (Metcalfe 2014, 102). With Paul’s ability through the authority of the ANB to influence a large voting demographic, Alaskan Natives influenced the outcome of elections during the first half of the 20th century.

The Paul-controlled ANB era eventually came to an end when the Peratroviches wrested the reins of power in the late 1930s, which caused a division within ANB that was devastating and long-lasting. William Paul and the Peratroviches would remain enemies until the end of their lives. Yet, the ANB that the Peratroviches inherited from Paul had become a powerful organization in Alaskan politics with a history of fighting for progressive, pro-Indian causes. Paul’s role in the fight against segregation is often forgotten due to the growing political and tribal recognition of the Peratroviches—Elizabeth in particular. However, Paul should rightly be remembered as an advocate whose struggles on behalf of Alaskan Native rights set an example for the Peratroviches to follow.

In time, the Peratrovich family wielded immense power in Alaskan Native politics: Roy served as Grand President of the ANB; Elizabeth served as Grand President of the ANS; and, Frank Peratrovich, Roy’s older brother, served as an Alaskan Territorial Senator (he would eventually serve as president of the Alaska State Senate after statehood) and ANB Grand President. The ANB, under the Peratroviches, set its sights on land claims, rejecting the imposition of reservations in Alaska, and constant vigilance over the federal government’s various pushes toward termination, statehood, and extinction of aboriginal title. The Peratrovich-led ANB also set its sights on ending Jim Crow segregation in Alaska.

There is no doubt the impetus behind the Peratroviches’ anti-discrimination bill came from Roy and Elizabeth’s lived experiences of segregation and discrimination, which they shared with thousands of Alaskan Natives across the territory. Shortly after Roy became the ANB Grand President in 1940, he took a job with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in Juneau. Upon arrival, the Peratroviches were denied housing in what was considered the “white” part of Juneau. The move from the small, mostly Tlingit village of Klawock, to the large city exposed Roy and Elizabeth to other forms of blatant discrimination and racism:

Signs in businesses and stores read “No Natives Allowed”, “We Cater to white trade only”, or advertised “Meals at all hours—All white help.” Natives in Juneau could only buy a home in certain parts of town, could only attend Indian schools. (CCTHITA 1991, 13)

Faced with such discrimination, Elizabeth organized lobbying efforts with other Tlingit women to confront Alaskan senators about the realities of discrimination and racism in the lives of Alaskan Natives. As Grand Presidents of the ANB and ANS, in December of 1941, Roy and Elizabeth wrote a letter to Governor Gruening, in which they denounced the hypocrisy behind Alaska’s legalized segregation: “In the present emergency [WWII],” they wrote, “our Native boys are being called upon to defend our beloved country, just as White boys. There is no distinction being made there” (CCTHITA 1991, 16). Roy and Elizabeth also attacked the hypocrisy of whites who expressed concern over the Jewish situation in Europe while turning a blind eye to what was happening in their own backyards:

We were shocked when the Jews were discriminated against in Germany. Stories were told of public places having signs, “No Jews Allowed.” All freedom loving people in our country were horrified at these reports yet it is being practiced in our country. We as Indians consider this an outrage because we are the real Natives of Alaska by reason of our ancestors who have guarded these shores and woods for years past. We will still be here to guard our beloved country while hordes of uninterested whites will be fleeing South. (CCTHITA 1991, 16)

That last sentence is especially interesting in that it was written just days after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. Roy and Elizabeth were insinuating that, should an Axis invasion of Alaska take place (as indeed it did when the Japanese captured islands in the Aleutian chain), Alaskan Natives would stay and fight for their country while, in their estimation, “hordes of whites” would make a mass exodus to the lower 48.

Roy and Elizabeth found in Governor Gruening a sympathetic listener who urged them to draft legislation prohibiting such discrimination in Alaska. With sample bills given them by Anthony Dimond (Alaska’s U.S. Congressman at the time), Roy and Elizabeth drafted their first anti-discrimination bill, which outlawed segregation and discrimination in public buildings, schools, housing, and private businesses. The bill was sent before the territorial legislature in 1943 and defeated by a vote of nine to seven after an intense and heated debate on the floor of the legislature. The dissenting legislators particularly disliked the fact that the bill would force local public schools to integrate.

Since the Alaskan Territorial Legislature met every two years, Roy and Elizabeth used the interim between 1943 and 1945 to garner support for their bill, both within and outside the Native community. On February 8, 1945, the anti-discrimination bill was once again before the legislature, but this time without the provision about public school integration. Governor Gruening had encouraged the Peratroviches to leave that out of the bill. He thought school integration too unrealistic a goal at the time and that it could come through later legislation.

Alaskan Natives won the day. The Peratroviches took on and defeated the pro-segregation contingent of senators and garnered enough votes to pass the bill. It became the first comprehensive anti-discrimination law of its kind in America. Governor Gruening would later reminisce, “Had it not been for that beautiful Tlingit woman, Elizabeth Peratrovich, being on hand every day in the hallways, it (the anti-discrimination bill) never would have passed” (CCTHITA 1991, 23). Governor Gruening signed the bill into law on February 16, 1945. Article One states:

All citizens within the jurisdiction of the Territory of Alaska shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of public inns, restaurants, eating houses, hotels, soda fountains, soft drink parlors, taverns, roadhouses, barber shops, beauty parlors, bathrooms, resthouses, theaters, skating rinks, cafes, ice cream parlors, transportation companies, and all other conveyances and amusements, subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law and applicable alike to all citizens.

Article Two of the bill delineates the punishment for those persons or businesses guilty of practicing or inciting discrimination and/or segregation.

In reality, there is large difference between the ideal of a law as expressed in a legal document, and the actual application of that law in everyday life. As Elizabeth stated in her debate with Senator Shattuck, having a law on the books never precludes the crime. Discrimination against Alaskan Natives remains a major problem. However, the anti-discrimination bill was an attempt to demand equality within American society that was not ready for complete equality; as such, the bill was ultimately ahead of its time.

As Alaskan Native leaders actively changing the status quo of Alaska and permanently altering the trajectory of Alaskan Native history, the Peratroviches were an integral part of American Indian history in the 20th century. The seeds of leadership were instilled in Peratroviches by previous Tlingit leaders, including grandmothers and grandfathers and clan leaders and warriors who had always been willing to organize in order to fight for their rights and properties. The Peratroviches, William Paul, and the ANB actively worked to change the future of Alaskan Natives and, in doing so, changed American history.

Biographies of Notable Figures

Elizabeth Peratrovich (née Wanamaker), whose Tlingit name was Kaaxgal.aat, was born on July 4, 1911, in Petersburg, Alaska. Elizabeth was a raven (the Tlingit tribe is divided into two halves or moieties—Raven and Eagle/Wolf—determined by matrilineal descent) of the Lukaax.adi clan. She was adopted when very young by Andrew Wanamaker and his wife Mary, both of whom were Tlingit. Wanamaker was a Presbyterian minister who worked across southeast Alaska. The village of Klawock was one of Andrew’s precincts, and thus the Wanamakers were familiar with the Peratrovich family. Elizabeth graduated from high school in Ketchikan, and attended Sheldon Jackson Junior College, a Native school in Alaska named after a minister who started the Alaskan Native education system. Eventually, Elizabeth would go on to attend Western College of Education (now Western Washington University) in Bellingham, Washington. She married Roy Peratrovich in 1931 and moved to Klawock, where she became actively involved in the Alaskan Native Sisterhood (ANS). Elizabeth would go on to become the Grand President of the ANS and to play an instrumental role in the passage of the 1945 Anti-Discrimination Act, which banned legal segregation in Alaska. Elizabeth also served as the ANB’s liaison to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) in Washington, D.C. Elizabeth passed away on December 1, 1958, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Juneau. In 1988, the Alaskan State Legislature established February 16 as Elizabeth Peratrovich Day, a state holiday in honor of her groundbreaking civil rights work.

Roy Peratrovich, whose Tlingit name was Lk’uteen, was born on May 1, 1908, in Klawock, Alaska. Klawock is a small Tlingit village located on the west side of Prince of Wales Island in Southeast Alaska. Roy was an Eagle whose ancestors were originally from Kuiu Kwaan. Roy had ties to the Flicker House (Kóon Hít) of the Naasteidi clan through his grandmother Kaatxweich (whose English name was Kitty Collins). Kaatxweich was a survivor of the 1860s smallpox epidemic. Originally hailing from Kuiu Island, as a young girl Kaatxweich escaped the utter devastation of her home village (Kuiu Kwaan) and made it to Klawock in one of several canoes laden with a small group of survivors who were mostly children. Eventually, Kaatxweich would become a powerful matriarch in Klawock and would live well beyond 100 years. Roy and his brothers and sisters learned much about leadership from Kaatxweich. Roy was sent to Chemawa Indian School in Oregon and attended Western College of Education (now Western Washington University) in Bellingham, Washington, where he married Elizabeth Wanamaker in 1931. Roy moved back to Klawock and served four terms as mayor of the village and five consecutive terms as Grand President of the Alaskan Native Brotherhood (ANB). He moved to Juneau in 1940 and spent the rest of his life actively involved in Alaskan Native politics. Roy passed away in 1989 and was buried next to Elizabeth in Evergreen Cemetery in Juneau.

William Paul, whose Tlingit name was Shgúndi, was born into the Teeyhittaan clan in 1885 in Tongass Village, Alaska. He was a Raven through his mother. His father disappeared during a canoe trip when he was one year old. William’s mother was left with two young boys (William and his brother Samuel) and pregnant with a third child. The Pauls eventually moved to Sitka, where William’s mother held a variety of jobs at the Sitka Industrial and Training School. When William was 14, he was sent to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. William graduated from Whitworth College, which at the time was a Presbyterian school in Tacoma, Washington. He attended seminary for a year in San Francisco and eventually settled on law for his graduate education. He took a correspondence course from Lesalle University of Philadelphia. He passed the bar exam in 1920, becoming the first Alaskan Native lawyer, and in 1923 he became the first Alaskan Native elected to the Alaska Territorial Legislature. William Paul was a key figure in the Alaskan Native Brotherhood; he was elected President of ANB, served as the organization’s attorney, and was instrumental in the getting the U.S. Court of Claims to hear a lawsuit brought by the Tlingit and Haida tribes against the United States government. After being pushed aside in preparation for that case, Paul took another lawsuit to the Court of Claims and, ultimately, to the U.S. Supreme Court (Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States) in 1955. Though he lost, the case did establish the key fact that Alaskan Natives had aboriginal title to the land, which would give Alaska Natives a basis for later land claims. Alaskan Native land holding might be vastly less today if it had not been for Paul’s Tee-Hit-Ton case. In the 1950s and 1960s, Paul would become a legal and political advisor to younger Alaskan Native leaders. Paul passed away in 1977.

DOCUMENT EXCERPTS

Testimony in the Senate on the Alaska Anti-Discrimination Bill

The Testimony from the Senate floor during the February 8, 1945, debate on the Alaska Anti-Discrimination Bill. Roy and Elizabeth Peratrovich, the architects behind the bill, were the only Indians who spoke during the debate.

Senator Tolber Scott: Mixed breeds are the source of trouble. It is only they who wish to associate with the whites. It would have been better if the Eskimos had put up signs “No Whites Allowed.” This issue is simply an effort to create political capital for some legislators. Certainly white women have done their part in keeping the races distinct. If white men had done as well, there would be no racial feeling in Alaska.

Senator Grenold Collins: I’d like to speak in support of Senator Scott. The Eskimos of St. Lawrence Island have not suffered from the White Man’s evil, and they are well off. Eskimos are not an inferior race, but they are an individual race. The pure Eskimos are proud of their origin and are aware that harm comes to them from mixing with whites. It is the mixed breed who is not accepted by either race who causes trouble. I believe in racial pride and do not think this bill will do other than arouse bitterness. Why, we should prohibit the sale of liquor to these Natives—that’s the real root of our troubles.

Senator Frank Whaley: I am also against the Equal Rights Bill. I personally would prefer not to have to sit next to these Natives in a theater. Why, they smell bad. As a bush pilot, I believe from my experiences that this legislation is a lawyer’s dream and a “natural” in creating hard feelings between whites and Natives. However, I will vote for this bill if we amend it by striking Section II which reads: “any person who shall violate or aid or incite such violation shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment in jail for not more than one month or fined not more than $50 or both.”

Senator O.D. Cochran: I am personally assailed by Senator Whaley’s remarks. I stand in support of the Equal Rights Bill. Discrimination does exist. In Nome, an Eskimo woman was forcibly removed from a theater when she dared sit in the “white section.” And I have a list of similar occurrences based solely on my own experiences that would occupy the full afternoon to relate.

Senator Walker: I too would like to state my support for the legislation. I know of no instance where a Native died of a broken heart, but I do know of situations where discrimination has forced Indian women into lives “worse than death.”

Roy Peratrovich: I would like to remind the legislature that the Honorable Ernest Gruening, in his report to the Secretary of the Interior, as well as his message to the legislature, has recognized the existence of discrimination. Even the plank adopted by the Democratic Party at its Fairbanks convention favors the Equal Rights Bill. In fact, members of that committee are present in this Senate body.

Senator Allen Shattuck: Mr. Peratrovich, as I mentioned to you before, this bill will aggravate, rather than allay the little feeling that now exists. Our Native cultures have ten centuries of white civilization to encompass in a few decades. I believe that considerable progress has already been made, particularly in the last fifty years, but still much progress needs to be made.

Roy Peratrovich: Only an Indian can know how it feels to be discriminated against. Either you are for discrimination or you are against it, accordingly as you vote on this bill.

Senator Allen Shattuck: This legislation is wrong. Rather than being brought together, the races should be kept further apart. Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites, with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind us?

Elizabeth Peratrovich: I would not have expected that I, who am barely out of savagery, would have to remind the gentlemen with 5,000 years of recorded history behind them of our Bill of Rights. When my husband and I came to Juneau and sought a home in a nice neighborhood where our children could play happily with our neighbor’s children, we found such a house and arranged to lease it. When the owners learned that we were Indians, they said no. Would we be compelled to live in the slums?

Senator Shattuck: Will this law eliminate discrimination?

Elizabeth Peratrovich: Do your laws against larceny, rape and murder prevent those crimes? No law will eliminate crimes, but at least you, as legislators, can assert to the world that you recognize the evil of the present situation and speak of your intent to help us overcome discrimination. There are three kinds of persons who practice discrimination: First, the politician who wants to maintain an inferior minority group so that he can always promise them something; second, the “Mr. and Mrs. Jones” who aren’t quite sure of their social position, and who are nice to you on one occasion and can’t see you on others, depending whom they are with; and third, the great superman, who believes in the superiority of the white race. This super race attitude is wrong and forces our fine Native People to be associated with less than desirable circumstances.

Senator Joe Green: Thank you, Mrs. Peratrovich. You may be seated.

Senator Walker: I move to close debate.

Source: Congressional Record, February 8, 1945.

The Anti-Discrimination Bill

The 1945 Anti-Discrimination Bill drafted and written by Roy and Elizabeth Peratrovich. It passed on February 8 and signed into law on February 16.

To provide for full and equal accommodations, facilities and privileges to all citizens in places of public accommodation within the jurisdiction of the Territory of Alaska; to provide penalties to violations.

Be it enacted by the Legislature of the Territory of Alaska:

Section 1: All citizens within the jurisdiction of the Territory of Alaska shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of public inns, restaurants, eating houses, hotels, soda fountains, soft drink parlors, taverns, roadhouses, barber shops, beauty parlors, bathrooms, resthouses, theaters, skating rinks, cafes, ice cream parlors, transportation companies, and all other conveyances and amusements, subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law and applicable alike to all citizens.

Section 2: Any person who shall violate or aid or incite a violation of said full and equal enjoyment; or any person who shall display any printed or written sign indicating a discrimination on racial grounds of said full and equal enjoyment, for each day for which said sign is displayed shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof shall be punished by imprisonment in jail for not more than thirty (30) days or fined no more than two hundred fifty ($250.00) dollars, or both. Approved February 16, 1945.

Source: Anti-Discrimination Act, House Bill 14. Session Laws of Alaska, 1945, 35–36.

Further Reading

CCTHITA. A Recollection of Civil Rights Leader Elizabeth Peratrovich, 1911–1958. Juneau: Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, 1991.

Cohen, Felix. “Alaska’s Nuremberg Laws/Congress Sanctions Racial Discrimination.” Commentary, 143, 1948.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Richard Dauenhauer, eds. Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors: Tlingit Oral Narratives. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1987.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Richard Dauenhauer. Haa Tuwuunaagu Yís, for Healing Our Spirit: Tlingit Oratory. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1990.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Richard Dauenhauer. Haa Kusteeyí, Our Culture: Tlingit Life Stories. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994.

Dombrowski, Kirk. Against Culture: Development, Politics, and Religion in Indian Alaska. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

For the Rights of All: Ending Jim Crow in Alaska. Directed by Jeffry Silverman. Blueberry Productions, 2009 (DVD).

Haycox, Stephen. Alaska: An American Colony. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Haycox, Stephen. “William Paul, Sr., and the Alaska Voters’ Literacy Act of 1925.” Alaska History 2:1 (Winter 1986/87): 17–38. Accessed 7/14/2015 http://www.alaskool.org/native_ed/articles/literacy_act/LiteracyTxt.html

Hope, Andrew and Thomas Thornton, eds. Will the Time Ever Come?: A Tlingit Source Book. Fairbanks: Alaskan Native Knowledge Network, 2000.

Kan, Sergei Symbolic Immortality: The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Laguna, Frederica de. Under Mt. St. Elias: The History and Culture of the Yakutat Tlingit. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972.

Metcalfe, Peter. A Dangerous Idea: The Alaska Native Brotherhood and the Struggle for Indigenous Rights. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2014.

Mitchell, Donald. Sold American: The Story of Alaska Native and Their Land, 1867–1959. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1997.

Paul, Fred. Then Fight For It! The Largest Peaceful Redistribution of Wealth in the History of Mankind and the Creation of the North Slope Borough. Victoria, Canada: Trafford Publishing, 2003.

Skinner, Ramona Ellen. Alaska Native Policy in the Twentieth Century. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1997.

Williams, Mary Shaa Tlaa, ed. The Alaska Native Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

Termination Policy, Mid-1940s to Mid-1960s

Megan Tusler

Chronology

1934 |

The Indian Reorganization Act (“Indian New Deal”) allows tribes increased management of their own assets. Termination effectively reversed this policy. |

|

1953 |

House Concurrent Resolution 108 calls for the termination of a number of tribes, some of which are designated by tribal affiliation, and others by the state in which the reservation is located. |

|

1953 |

Public Law 280 extends criminal and civil jurisdiction to some states with respect to the Indian nations housed within their borders. |

|

1954 |

Individual termination acts begin application. This ends the trust relationship between the federal government and 110 tribes and bands in eight states. |

|

The final termination act is passed. |

||

1975 |

The passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (Public Law 93–638) ends termination policy by producing relationships between government agencies and tribes. These include the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and the Department of the Interior. |

The Termination of Federal Supervision and Control of American Indians

Termination, as a dynamic of federal American Indian policy, is generally referred to as the “termination era,” because the decisions to end federal trust relationships with American Indian nations spread out over a number of years. The primary act, however, was House Concurrent Resolution 108, passed in 1953. It reads, in part: “That it is declared to be the sense of Congress that, at the earliest possible time, all of the Indian tribes and the individual members thereof located within the states of California, Florida, New York, and Texas, and all of the following named Indian tribes and individual members thereof, should be freed from Federal supervision and control and from all disabilities and limitations specially applicable to Indians: The Flathead tribe of Montana, the Klamath tribe of Oregon, the Menominee tribe of Wisconsin, the Potowatamie tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, and those members of the Chippewa [Ojibwe] tribe who are on the Turtle Mountain Reservation, North Dakota.” “Freed from Federal supervision” is the telling phrase of this act. In practice, this “freedom” meant that the nations named were to be effectively unrecognized by the federal government and the institutions under it that served Indians, particularly the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.