PEOPLE, PLACES, AND ENVIRONMENTS

WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP OF NATIVE AMERICANS TO THE ENVIRONMENT?

In the 1970s, America’s imagination was captured by the “Keep America Beautiful” television ad, which featured a purported Native American dressed in traditional regalia with a tear running down his cheek at the site of polluted land and water. While that vivid image has some basis in traditional values, it is overly simplistic.

Traditional Native American sensibilities regarding the earth and the human relationship with it are elucidated in these words of the writer, actor, and chief Luther Standing Bear from his book, Land of the Spotted Eagle (1978): “The Lakota was a true naturist— a lover of Nature. He loved the earth and all things from the earth….From Wakan Tanka there came a great unifying life force that flowed in and through all things— the flowers of the plains, blowing winds, rocks, trees, birds, animals— and that was the same force that had been breathed into the first man. Thus all things were kindred and brought together by the same Great Mystery.”

As people who see themselves as part of the natural world— not separate from it— Native Americans come from cultures that value balance and strive to live in a way that respects and preserves it. When things become imbalanced, sickness, unhappiness, and confusion are the results. Then it is the human responsibility to take steps, including conducting ceremonies, to restore the balance and harmony necessary for the appropriate functioning, not only of humans but also of all things.

Like all people, Natives have traditionally obtained food, clothing, tools, transportation, homes, and medicines from the environments in which they have lived. Because Native Americans are tied philosophically and spiritually to their resources, however, they treat them with respect. Native Americans express veneration not only in ceremonies but also in the careful management of certain resources.

MPI/Archive Photos/Getty Images

A gathering place for traders and salmon fishers for thousands of years, Celilo Falls, on the Columbia River in Oregon, was submerged by the opening of The Dalles hydroelectric dam on March 10, 1957. Today the Columbia River is broken up by fourteen hydroelectric dams, and the 14 million wild salmon that inhabited the river in 1855 have dwindled to fewer than 100,000. Native fishers spearing salmon from wooden scaffolds at Celilo Falls, ca. 1940.

Before the arrival of Europeans, many Native Americans used their knowledge of the environment in the practice of agriculture. With fire and tools they cleared trees and brush to make room for fields of corn, beans, and squashes. Companion-planting the three crops helped rejuvenate the nitrogen in the soil, keep insect infestations down, and maintain moisture in the soil. According to a USDA Forest Service report issued in 2013, Native Americans across North America also cleared vast tracts of land with fire. “Native Americans used fire for diverse purposes, ranging from cultivation of plants for food, medicine, and basketry to the extensive modification of landscapes for game management or travel.”

Many modern Native Americans feel these traditional connections to the earth. Communities still practice their traditional arts, agriculture, and ceremonies related to the environment. In response to modern challenges, many tribal governments are addressing environmental issues that affect their communities. The Karuk tribe of northern California is one of many that have fought to preserve salmon spawning runs in the rivers of the Northwest. Power-generating dams built on rivers in the mid-twentieth century severely depleted salmon runs. That encroachment not only interrupted the ancient cultural connection to the salmon but also affected the diet of tribal members, such as the Karuks, who believe that epidemics of obesity, heart disease, and early-onset diabetes are related to the dams. In another example, the Colville tribal members of Washington State recently rejected an opportunity to open a molybdenum (a metal used to harden steel and dye plastics) mine on their reservation. While the mine would have offered some economic opportunities, it was rejected on the basis of its impact on the reservation environment and traditional culture.

The late Native American scholar and philosopher Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux) described the difference between Western and Native American understandings of the universe in an interview published in 2000:

I think the primary difference is that Indians experience and relate to a living universe, whereas Western people— especially scientists— reduce all things, living or not, to objects. The implications of this are immense. If you see the world around you as a collection of objects for you to manipulate and exploit, you will inevitably destroy the world while attempting to control it. Not only that, but by perceiving the world as lifeless, you rob yourself of the richness, beauty, and wisdom to be found by participating in its larger design.

— EDWIN SCHUPMAN

WERE THE AMERICAS A VAST, UNTOUCHED WILDERNESS WHEN EUROPEANS ARRIVED?

By the time Europeans arrived in the Americas, Indigenous peoples— thousands of cultures, each with different languages, belief systems, and lifeways— had occupied all regions of the Western Hemisphere for millennia. Far from being a virgin landscape, the Americas were home to an estimated 72 million people who expertly and sustainably managed their environments through agriculture and engineering to produce food, medicine, shelter, tools, and more. Some peoples used the land lightly; others established vast cities, roads, and empires.

All aspects of Native peoples’ lives— food, clothing, architecture, language, social structure, and spirituality— evolved from their local environments, whether that was the icy Arctic, the Southwestern deserts, or expansive plains. Native peoples engineered their homes to suit the landscape: adobe pueblo homes of the Southwest insulated against the intense heat and cold, portable tipis allowed Great Plains tribes to travel to hunt bison, and building homes on stilts allowed people to stay dry in the riverine floodplains of Peru. The environment also determined peoples’ food sources. People in the desert Southwest perfected dry farming, while tribes in what is now California farmed very little because of the abundance of food sources, from river and ocean fish to acorns and animals in the mountains. Lack of large agriculture didn’t mean lack of land use, however. California peoples, for example, regularly managed their environments using controlled burning. One of the main food staples in the region was acorns from oak trees. Seasonal controlled burning removed undergrowth that competed with oaks for water and nutrients, encouraged grasses that attracted game, served as a non-chemical pest control, and reduced the impact of catastrophic wildfires. Native peoples managed their environments using controlled burning, erosion control, fish and waterway management, and other inventive techniques to optimize the resources that were already there.

Several factors contribute to the myth of the American wilderness. It was in the interest of European colonists to justify taking land by asserting that the Indigenous people weren’t using or improving it, in spite of the evidence of extensive Native occupation and wide-scale farming. The fact that disease was wiping American Indians out via trade routes before some Native communities even came into contact with Europeans was proof to colonists that God was making way for their settlement. As scholar David E. Stannard observed, according to English colonists, “God was making a place for his Christian children in this wilderness by slaying the Indians with plagues of such destructive power that only in the Bible could precedents for them be found. His divine message was too plain for misinterpretation.” Instead of the garden that Indigenous people meticulously cultivated, the landscape was used as a backdrop for manifest destiny.

Indigenous peoples and Europeans thought about nature in drastically different ways. While the Native peoples had been using the environment in ways that would sustain their communities, the Europeans who arrived sought to exploit the Americas for wealth. Journals written by early observers— including Columbus himself— included few descriptions of nature beyond how it could be commodified and sold in Europe. As scholar Kirkpatrick Sale observed, English colonists wrote of their fear of nature: “To this terror of the wild the European mind opposed the serenity of the garden: nature tamed, nature subdued, nature, as it were, denatured.” Once settlements were established, settlers began to clear cut forests and overhunt game (such as the beaver) to the point of near extinction. Elimination of nature and game led to widespread degradation of the environment, including erosion and pollution. Defining nature by commodities— how much wood can be cut down, how many beaver pelts can be sold, etc.— was a very different world view from that of the Native peoples and was a fundamental reason why Europeans saw the Americas as uninhabited, despite the civilizations that already occupied the continents. Rather than the mythical wilderness that settlers imagined occupying, the Americas were home to millions of people who had been conserving, cultivating, and managing the landscape for millennia.

— ALEXANDRA HARRIS

© John Carter Brown Library, Box 1894, Brown University, Providence, R.I. 02912

The Tovvne of Secota in A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia by Thomas Hariot (1560–1621). This engraving by Theodor de Bry (1528–1598) depicts Secoton village, possibly in North Carolina. Buildings of pole-and-mat construction are dispersed in the landscape and surrounded by fields of corn, tobacco, sunflowers, and pumpkins. Also shown are people hunting deer, guarding a field, tending a fire, and eating and dancing.

DID NATIVE PEOPLES AND EUROPEAN COLONISTS HAVE DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES ABOUT LAND?

During initial encounters with each other, Native peoples and Europeans had very different ways of thinking about land. Europeans viewed land ownership as an expression of personal independence and economic self-sufficiency, which wasn’t possible to attain in Europe at the time. They based their property rights on deeds, surveys, and written documents. The young colonies, their towns, and individual colonists all purchased land from Native peoples and recognized the Indian ownership of land. At the same time, they saw Native people and their land as wild, savage, and chaotic. Their European definitions of land imposed order on what they saw as a wilderness.

Native peoples had a deeper relationship to the land. The land was the foundation of their existence and at the center of their creation stories. It was the origin of their sovereignty, identity, spiritual practices, and cultures. For many tribes, the plants, animals, and forces of nature were all equally important actors in the living universe. Tribes had territories that they defended against invaders; families and individual tribal members owned rights to certain tracts of land for hunting, farming, and fishing. They didn’t sell these rights to each other, but asked permission for use or to cross another tribe’s territory. Villages relocated periodically for different reasons, so land rights were inherently temporary. When fields were depleted, for example, a village might temporarily rotate off that land or move location entirely, changing a tribe’s territorial boundaries. Ecologist M. Kat Anderson described a California Indian concept of ownership as usufruct, meaning to use but not possess. “Under the usufruct system,” she wrote, “each family had a combination of exclusive rights to certain resources and communal rights to other resources.” Individual oak trees might be privately owned, while another area of oaks might be owned by the tribe in common. Additionally, Native people didn’t accumulate wealth in the same way Europeans did, so there was no reason— or need— to buy and sell land.

Early agreements between colonists and Eastern Native Americans show evidence that these differences led to misunderstandings, the most famous being the sale of Manahatta, or Manhattan Island. When approached by Europeans to sell land, Native peoples likely viewed these transactions as the purchase of rights to use the resources in a specific area, just as fellow members of the tribe would do. In this way, the same plot of land might be sold repeatedly to different buyers, a tendency that colonists complained about frequently.

Native people learned quickly, however, that land sales meant something very different to the colonists and that the newcomers did not share traditional Native conceptions of land. After initial encounters (and the clashes that resulted from misunderstandings), Indians began to reserve rights, such as the right to fish, hunt, or gather wood, from the sale of territory. The fact that these rights are named and included in land sales documents implies that Indians well understood the necessity to negotiate continued rights; without them, the English would think they had the authority to evict Indians from the land.

Notably, Northeastern Native peoples who achieved literacy with their languages began conveying land to one another via written contracts as early as the fifteenth century. Nantucket people began writing their own deeds in the 1660s, separate from the English deed-title system. Indians who spoke the Massachusett language, who may have been more literate than nearby colonists in the eighteenth century, confirmed oral agreements between tribal members with written contracts.

Today many tribes still recognize family and tribal territories, formally and informally. During powwows and formal gatherings, organizers invite a local tribal leader to welcome visitors to their territory. In many cases on the tribal level, family territories are still recognized and custom requires that other families ask permission to use that parcel of land.

— ALEXANDRA HARRIS

DO ALASKA NATIVES REALLY HAVE HUNDREDS OF WORDS FOR SNOW?

It is true that the Yup’ik and Iñupiaq peoples of northern Alaska and the Inuit people of northern Canada have a seemingly unlimited number of words and phrases that describe types, textures, and amounts of snowfall. Many other words describe different conditions that exist when snow is on the ground. Yup’ik and Iñupiaq are only two of Alaska’s eleven culture groups, but in those languages single words can often express detailed descriptions.

The vast array of snow descriptions in Yup’ik and Iñupiaq is possible largely because the languages are polysynthetic, meaning that entire sentences can be formed by a single word. Many different suffixes also can be added to a root word, such as snow, making it possible for the Yup’ik and Iñupiaq to say in one word what an English speaker would need several words— perhaps even an entire sentence— to say.

Types of snowfall include such simple conditions as lightly falling snow, heavy wet snow, blowing snow, and others. Because Native peoples have always had to understand the land on which they live with an eye toward communal survival, it makes sense that weather would be closely monitored by Indigenous peoples, particularly those in climates where changes in weather can be extreme. Describing a weather condition in detailed language— and adapting one’s behavior to more easily live with it— is a practice common to many other Native peoples, including Native Hawaiians, who have countless words to describe rain (for example, rain that sweeps over the ocean to the islands; misty, cool rains of the valley regions; torrential downpours in the rain forests), an important feature of their tropical environment. Because snow is an important part of many Native Alaskan people’s environment (in northern Alaska, snow covers the ground for most of each year), the ability to describe the various kinds of snow was— and continues to be— crucial to their survival on the land.

Here is a list of a few of the different types of snow that have been described by Inuit people, in just one dialect, the Copper Inuit: aniu (good snow to make drinking water); apiqqun (first snow in autumn); apun (fallen snow); aqilluqaq (fresh soft snow); mahak (melting snow); minguliq (falling powdered snow); natiruvik (snow blowing along a surface); patuqun (frosty sparkling snow); pukka (sugar snow); pukaraq (fine sugar snow); qaniaq (light soft snow); qanik (snowflake); qanniq (falling snow in general); qayuqhak (snowdrift shaped by the wind, resembling a duck’s head); and ukharyuk, qimuyuk, aputtaaq (snowbank).

— LIZ HILL AND NEMA MAGOVERN

DID INDIANS REALLY USE SMOKE SIGNALS? DO THEY TODAY?

Yes. Some Native peoples living on the Great Plains and in the Southwest used smoke signals hundreds of years ago. For example, the Navajo and Apache transmitted smoke signals as a military tactic to warn of the approach of enemies. But the use of smoke to convey messages has been greatly exaggerated— and even ridiculed— in twentieth- and twenty-first-century mainstream popular culture, particularly in Hollywood movies, advertisements, and cartoons.

The image is now deeply ingrained in the public consciousness. Think of it: a Native man, dressed in the style of the Great Plains cultures, long hair in braids with a headband and feather, sits on the edge of a cliff (of course in the “Indian style,” with his legs crossed in front of him). The Indian man is fanning a fire with a blanket, from which smoke billows upward. His smoke “signals” are received and interpreted by another Native man, perhaps miles away.

American popular culture also has distorted the rudimentary character of smoke signals and would have the average person believing that an entire language has been built around their use. Native peoples did not use smoke to spell out entire words, as is often depicted in the media. Neither did all tribes use smoke to communicate. Today, when someone mentions smoke signals, the image of an Indian immediately comes to mind. When asked by Cineaste magazine about the title of his film Smoke Signals (1998), author Sherman Alexie (Spokane/Coeur d’Alene) said, “On the surface, it’s a stereotypical title; you think of Indians in blankets on the plains sending smoke signals, so it brings up a stereotypical image that’s vaguely humorous. But people will also instantly recognize that this is about Indians.”

Indian people no longer use smoke signals as a mode of communication. News and information that travel from one Native American person to another— and to others around the country— are sometimes said jokingly to travel on the “moccasin telegraph” (or, in the case of Native Hawaiians, on the “coconut wireless”), which is a way of acknowledging the speed at which news travels to Native communities no matter how far apart they are located.

Native people today communicate by cell phone, email, social media, telephone, and text.

— LIZ HILL

DID NATIVE AMERICANS USE SIGN LANGUAGE?

Many tribes in North America used sign language from before European contact through the twentieth century. Sign language was common throughout the Americas, although its use has been most frequently documented from northern Mexico all the way into southern Canada.

Although sign language was used in tandem with everyday speech— and still is today in some communities— it is a method of communication completely independent of any one language. It is a fully functional language unto itself and enables an individual to communicate varied and complex ideas just as spoken languages do. All tribes didn’t necessarily use the same signs. Just as speakers of the same language have different dialects, so do practitioners of Indigenous sign language, sometimes referred to as American Indian sign language or Plains Indian sign language. As linguist Jeffrey E. Davis observed, sign language is a “universal linguistic phenomenon,” but that doesn’t necessarily mean that all signs used by different peoples are mutually intelligible. Regional differences in sign language gestures can be compared to regional differences in a spoken language— vocabulary as well as speed and style of delivery may differ depending on the tribe. These differences do not prevent the individuals using sign language from understanding one another. Likewise, American Indian sign language instructor Shawn Ware (Kiowa) recalled what older generations have told him: “As long as there is communication and clear understanding, there is no wrong sign.” While American Indian sign language is still practiced, it is not used as frequently today as it was in previous generations. Nonetheless, new signs continue to be created, especially to address technological advances.

Photo by C. M. (Charles Milton) Bell. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution NAA INV 00866700

Portrait of Tendoi (Shoshone) demonstrating sign language, ca. 1800s.

Historically, sign language has served many different purposes. In addition to providing a means of communication for deaf people, it enabled the exchange of information between those who spoke completely different languages. It was also used in hunting and war situations, where stealth and secrecy were required, and for communication from a distance when speech wasn’t possible. Trade was likely a major factor in its development. The Americas are home to hundreds of Native nations, many of whom have mutually unintelligible languages. Sign language served as a lingua franca, or a common language, that allowed speakers of different languages to communicate.

Sign language was probably also used during treaty negotiations between the United States and American Indian nations and to recount historical events. Treaty scholar and anthropologist Raymond DeMallie observed, “What we don’t see referred to in the record, and I think it’s important to realize, is that traditionally when Plains Indians spoke in council, they said everything that they had to say in speech also simultaneously in sign. The sign language was universal throughout the plains, and it was tremendously valuable….So I think probably the substance of what the white commissioners had to say was very well communicated. The meaning is another question.” Jeffrey Davis further reflected on the capacity for sign language to be used to recount histories. He noted that one of the best-known eyewitness accounts of the Battle of Little Bighorn was originally told by Lakota Chief Red Horse in sign language, then translated into English.

As a lingua franca for many American Indian peoples, sign language was a way to facilitate communication across linguistic and tribal boundaries. Signs were shared between people and communities, and users creatively devised the signs they needed. While English is the present-day common language, sign language endures and is still used inventively in many Native communities.

— ALEXANDRA HARRIS

WHAT KINDS OF FOODS DO INDIANS EAT?

Who hasn’t experienced the enticing smell of popcorn upon entering a movie theater or enjoyed a big bowl of potato chips and guacamole while watching the Super Bowl game? These are just a few of the sumptuous foods that have their origins among Native Americans of the Western Hemisphere. At the top of the long list of plants grown or processed by American Indians are corn, beans, squashes, pumpkins, peppers, potatoes, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, peanuts, wild rice, chocolate, pineapple, avocado, papaya, pecans, strawberries, blueberries, cranberries, and sunflowers. More than half the crops grown worldwide today were initially cultivated in the Americas.

American Indians hunted, herded, cultivated, and gathered a vast variety of species. The sciences of plant cultivation and food preparation were highly developed in the pre-Columbian Americas. By the time of the Spanish invasion in 1492, Indians in the Andes had developed more than a thousand different species of potato, each of which thrived in distinct growing conditions. Native Americans throughout the hemisphere developed at least as many varieties of corn to suit climates ranging from the northern woodland areas to the tropics. Today corn grows over a larger area than does any other cultivated food in the world.

The people of northeastern North America were among those who recognized the symbiotic relationship between corn, beans, and squashes: the bean climbs the natural trellis of the corn stalk, while the squash shades the ground below, discouraging other plants from spreading and choking the corn roots. Each plant also gives and takes different nutrients from the soil. The people of the Iroquois Confederacy called these crops the Three Sisters, or the sustainers, because of their importance to the well-being and survival of the people.

Many foods and food techniques have changed little from those developed by Native people. Modern manufacturers ferment, dry, and roast cacao beans to extract chocolate in much the same way as did Maya and Aztec growers. Along the North Pacific Coast, salmon is dried and smoked using processes that have existed for millennia. On the Great Plains, buffalo was the fundamental food source— entire cultures developed around communal buffalo hunts. Today Native breeding programs are restoring buffalo populations, making the meat available as a healthy alternative to beef.

Since reservations were first established in the late nineteenth century, many American Indians have depended on nontraditional, government-issued food commodities, from which has arisen one of the most delicious and least healthful “Native” foods: fry bread. Made with flour, yeast, and lard, fry bread is served warm with powdered sugar or syrup, or loaded with meat, cheese, shredded lettuce, and tomato to make another familiar treat: the Navajo (or “Indian”) taco.

Most Native people today eat the foods that other Americans do, but traditional foods such as salmon, venison, wild strawberries, varieties of beans and chilies, and especially corn remain integral to seasonal ceremonies, dances, and other special occasions throughout Indian Country. Increased nationwide interest in fresh, local foods has led to renewed cultivation of Indigenous ingredients and the creation of nontraditional dishes that bring out their flavor.

So, when you dig into a bowl of chili, a pile of mashed potatoes, or a piece of pumpkin pie, remember that such seemingly modern dishes depend on ingredients that were first cultivated, cooked, and given to the world by Native Americans.

— STEPHANIE BETANCOURT

Painted tribute record of Tepexi de la Seda, 18th c. copy of ca. 16th c. original. Puebla, Mexico. 8/4482

A record of tribute paid by Native people to Spanish overlords. Items pictured include slaves, gold, precious stones, fine feathers, textiles, cacao, chickens, sandals, woven chairs, rattles, gourd vessels, bowls, pots, and pitchers. A detail from the painting shows some of the principal crops grown by Native people in the region: cotton, corn, squash, and peppers.

BEFORE CONTACT WITH EUROPEANS, DID INDIANS MAKE ALL THEIR CLOTHING FROM ANIMAL SKINS?

No, not all clothing was made of animal skins, furs, or other animal parts. Many American Indians made their clothing from plant materials, including cotton and yucca, and from wool. Between 3500 BC and 2300 BC, Native people in Mesoamerica and on the eastern slope of the Peruvian Andes domesticated many varieties of cotton, a plant that is indigenous to the Western Hemisphere. Archaeologists have found seven- to eight-thousand-year-old mummies wrapped in cotton textiles, and it is possible that wild cotton was used for clothing in Peru as early as 10,000 BC. American Indians in southwestern North America began growing cotton shortly after 1500 BC, and the earliest textile found in present-day New Mexico dates back to AD 700. As early as AD 300, ancestral Puebloans were gathering other plant fibers, such as yucca, willow, and juniper bark, processing them, and weaving them into sandals, blankets, leggings, socks, belts, and other articles of clothing.

Today, Native people wear all kinds of modern attire, just like everyone else. Almost all tribes, however, continue to wear traditional and dance clothing, which is customary for social and ceremonial occasions. Ceremonial wear is made of modern textiles in addition to other materials— including animal skins— that predate the arrival of Europeans.

— MARY AHENAKEW

18/946

Nazca poncho (detail) made of camelid fiber and plant fiber, AD 1000.

IS IT TRUE THAT NATIVE PEOPLE USED ALL PARTS OF THE ANIMAL?

Native peoples used as many parts of the animal as they could. Native communities were keenly aware of the resources they needed for survival and the methods they could use to ensure a food source. They were subsistence hunters, as opposed to hunting with the intent to sell or trade, and they knew that overhunting meant less food in the future. As a result, they endeavored to sustainably manage their environments to protect the plants and animals consumed. For example, controlled burning was widely used to regulate animals’ food sources and to corral or flush out game. Native peoples took great pains to nurture and control hunting territories both to attract game and to remove obstacles.

Once game was captured, it only made sense to figure out how different parts of the animal could be used. Having lived in their homelands for hundreds of years, Native peoples became experts in how to derive benefits from the flora and fauna. They tested, experimented, and refined their resources. Animal skins were used for everything— homes, clothing, bags, drums, and more. Sinew was used to sew and tie objects together and for bowstrings. What could you do with a buffalo’s shoulder blade? Attached to a stick, it worked well as a shovel. And its horns? Whole horns could be fashioned into a cup; halved horns could be carved and bent into spoons. Deer toes became rattles or glue while teeth were used as decoration for clothing. Bladders were dried and used to carry water. For the Blackfeet, a northern Plains tribe, the buffalo provided more than one hundred different items of material culture. In short, in a subsistence economy where resources were not always plentiful, inventiveness was essential for survival.

Hand-colored lantern slide of Uliggaq (Ella Pavil, Yup’ik), dressed in a seal-gut parka and standing next to a dip net full of tomcod, 1935. Kwigillingok, Alaska. L02290

At the same time, it was not always possible to use all of an animal and there were undoubtedly situations where resources were wasted. Survival sometimes required people to butcher an animal where it fell and transport what they could to their village or camp. The Great Plains tradition of a buffalo jump is one example of hunting where it may only have been possible to butcher lightly rather than taking everything. A buffalo jump typically occurred when hunters— men and women— encouraged buffalo over a cliff, where they fell to injury or death. Dozens and possibly hundreds could be killed at once. While at times all edible parts of the animal would be taken back to the village for consumption or preservation, at other times the unused buffalo remained where they died. The demand for meat determined how much was used.

It bears mention that wise use of hunted animals was not just for practical purposes. In many tribes, traditions teach and require giving thanks to the animal that has died so that people may eat. Many of those traditions dictate that the animals are relatives. Some Pueblos in the Southwest believe that their ancestors return as deer—a belief that necessitates expressing appreciation during a hunt and discourages waste. This tradition endures today.

So while all parts of the animal may not have been used after every hunt, Native peoples devoted much energy to ensuring the survival of their community by working to sustain wildlife populations. Overhunting may indeed have occurred before European contact, but it was only after European settlement and the introduction of game and fur (mainly buffalo and beaver) to the colonial and European market economy that Natives and non-Natives caused the decimation of species and ecosystems.

— ALEXANDRA HARRIS

IS IT TRUE THAT NATIVE AMERICANS HUNTED A GREAT NUMBER OF LARGE ANIMALS TO EXTINCTION?

There continues to be a debate in scientific circles about whether or not Paleo-Indian peoples living on the American continent during the thousands of years before and during the Pleistocene epoch (1.8 million to about ten thousand years ago— this was also known as the period of the ice ages) contributed to the extinction of the great variety of animals that were known to have inhabited the land. The existence of an incredible array of plant, animal, bird, and other nonhuman life in the Western Hemisphere during the ice ages is not in doubt. What is less certain is exactly how all of these living beings disappeared during a relatively short period about ten thousand years ago. Did the ancestors of today’s Native peoples hunt and kill large numbers to extinction? One theory suggests that they did. Another argues, however, that climatic and environmental changes caused by retreating glaciers wiped out many North American creatures, both large and small.

Most scientists believe that it was also during the Pleistocene, approximately fifteen thousand years ago, that waters receded in the strait that linked Siberia and Alaska, thus creating a “land bridge” that made it possible for people to make their way onto the North American continent. This theory— which is vigorously debated by scientists and Native peoples, many of the latter believing their ancestors have always been on the continent— contends that successive generations of northern nomadic peoples, traveling in small bands, made their way from Alaska to southern South America. Their numbers grew along the way— some scientists believe that the population could have grown relatively quickly into the millions. Certainly, when one looks at the population estimates for the Western Hemisphere just before Columbus’s arrival, with Indigenous peoples perhaps numbering more than 70 million, the idea doesn’t seem farfetched.

There is no doubt that the array of animals living on the American continent was at one time significantly more diverse than it is today. In 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus (2005), Charles C. Mann describes the scene as an “impossible bestiary of lumbering mastodon, armored rhinos, great dire wolves, saber tooth cats and ten-foot-long glyptodonts like enormous armadillos.” He continues, “Beavers the size of armchairs; turtles that weighed almost as much as cars; sloths able to reach tree branches twenty feet high; huge, flightless, predatory birds like rapacious ostriches— the tally of Pleistocene monsters is long and alluring.”

Then, suddenly, all of these beasts were gone, rapidly disappearing from the earth around ten thousand years ago. Today’s relatively small Indigenous population may make it difficult to imagine a late-Pleistocene continent teeming with humans, but one theory raises the possibility that the animals could have been killed off by human overhunting. The other argument— equally convincing— is that the end of the last ice age killed off the animals. Lending more weight to the second theory is the simultaneous disappearance of plants and other nonanimal species during that time of great climatic disruption.

Some evidence, however, supports the theory that some Native cultures, such as the Maya of Central America, may have depleted their natural resources— including animal life— thus contributing to their own eventual collapse. But more recently it was Europeans and Americans who nearly exterminated the North American buffalo, and commercial whalers— not Indigenous people— who drove whales to the brink of extinction.

— LIZ HILL

WHY DO INDIANS WEAR FEATHERS? WHY ARE EAGLE FEATHERS SO IMPORTANT TO INDIANS?

Known as the Thunderbird in many Native American cultures, the eagle is said to be the messenger between humans and the Creator, flying higher and seeing farther than any other bird. The feathers of the eagle, which help send messages to the Creator, represent prayers. Eagle feathers are used in ceremonies, worn as part of powwow regalia, or given away as honoring gifts— all to show respect to the eagle and maintain a spiritual and physical connection to this sacred creature.

Greatly prized, eagle feathers are often handed down from one generation to the next, both individually and as part of a person’s regalia. The feathers are either obtained naturally— from eagles that have died or molted— or from the National Eagle Repository in Denver, Colorado, a government facility where members of federally recognized tribes can legally acquire them. Recognizing the ceremonial value of eagles to American Indians, lawmakers granted this important exception to the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940 (amended in 1962 to include golden eagles), which makes it illegal for anyone to possess eagle feathers or eagle parts.

Powwow dancers consider eagle feathers to be the most important item of their dress, and any part of an eagle used by a dancer— the beak, talons, and bones, for example— are treated with respect and honor. Eagle feathers are treated with great care throughout the powwow in many ways. If an eagle feather accidentally falls off a dancer’s clothing during a powwow dance, a war veteran or the Arena Director will stand next to the feather to protect it. At the end of the dance, the powwow arena is cleared and a ceremony is held to retrieve the feather. In addition, feathers are often given away to dancers formally entering the arena for the first time, or to celebrate an individual achievement.

William H. Rau. Portrait of a Sioux man, entitled Chief Iron Tail—Sinte Maza, ca. 1901. North or South Dakota. P27530

In the past, tribal warriors earned eagle feathers when they demonstrated bravery, either in battle or on the hunt. Sometimes a feather would be painted or cut in a certain way to tell the story of how the feather was earned. For many non-Native people, the image of an elder or tribal leader wearing a long eagle-feather war bonnet is powerful and familiar. Plains Indian leaders and warriors did wear these beautiful headdresses— and still do today for ceremonial purposes. Wearing eagle feathers in such a way indicates rank or personal achievement.

Today as in centuries past, Native people use feathers of all kinds to decorate their dance wear, stabilize arrow shafts, weave elaborate robes and cloaks, and adorn baskets or jewelry. Tribes in certain regions honor hawks, kingfishers, ravens, woodpeckers, and hummingbirds. For many, these unique creatures of the air have great spiritual significance; by using and wearing the feathers of these birds, one can access their powers and honor them.

— TANYA THRASHER

HOW DID NATIVE AMERICANS ACQUIRE HORSES?

Scholars generally agree that Native Americans initially acquired horses from the colonial Spanish herds brought to present-day New Mexico. Some horses were captured in raids, but most were apprehended during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. In August 1680 the Pueblo Indians of northern New Mexico mounted an uprising against Spanish colonizers and drove them from Native lands. The strategic move to steal the Spaniards’ horses guaranteed the success of the revolt and introduced the horse as a permanent fixture in Native life and culture. This horse population of Spanish origin then expanded rapidly across North America, moving north and east along established Native trading networks. The horse quickly gained popularity and prominence throughout Native society, particularly with Western tribes, such as the Nez Perce and Blackfeet of the far Northwest, the Kiowa and Comanche of the southern Plains, and the Arapaho, Crow, Cheyenne, and Sioux of the northern Plains.

The introduction of horses to Native peoples opened up new possibilities. Tribes could hunt more efficiently, travel farther, and transport items from camp to camp with ease. Horses became such a central component of Native culture that definitions and ideas about what constituted wealth began to shift. Mass herds increased Native peoples’ leverage and power in trade networks, territorial expansion, and warfare. While horse culture increased mobility and became a symbol of wealth, prestige, and honor, it also introduced new problems. Intertribal warfare, conflicts with white settlers, and the overharvesting of buffalo were negative aspects of the horse revolution in Native society.

Horses changed life most profoundly on the Great Plains and became integral to Plains cultures. Horses allowed these tribes to better defend themselves as settlers and soldiers encroached on tribal lands. Attacks carried out by the U.S. military and vigilante groups forced Plains tribes to adapt and transform their approach to warfare, placing horses at the center of Plains peoples’ survival. Horses made fighters swift in battle and were considered comrades in arms. Horses became so prized that many Plains tribes began the practice of painting and decorating their horses. Horse masks made of buffalo skin and then painted with pigment were decorated with pony beads, brass buttons, and a mixture of horse and human hair. These elaborate masks signaled strong spiritual overtones and intimidated enemies.

Pretty Beads, a Crow girl, carries her doll and cradleboard fastened to the pommel of her horse’s saddle. N41420

Today the horse remains extremely important to Plains Indian life. The Crow Fair, for instance, held during mid-August at Crow Agency, Montana, speaks to the continued centrality of the horse to Native life and culture. The event attracts skilled Native horsemen and horsewomen from as far away as Pine Ridge in South Dakota to Fort Hall in Idaho and includes competitions in sprint races, team roping, and women’s calf roping. Without a doubt, however, the horses are the main attraction at Crow Fair. They debut with great pageantry in finest dress, adorned with elaborately beaded masks and accoutrements. Plains tribes continue to manage their own herds today and also help to protect wild horses, symbols of Native pride, healing, and spiritual wealth.

— BETHANY MONTAGANO

WHERE DID NATIVE PEOPLE GET GLASS BEADS TO DECORATE THEIR CLOTHING?

Before the introduction of glass beads by European colonists in the mid-1700s, Native peoples depended on materials derived from their environment to decorate clothing. Some of the earliest dresses and shirts were painted with natural materials, known as earth paints. Minerals and clays were frequently used and would often be combined with buffalo fat and mixed in bowls made out of turtle shells to make paints. In addition to paints, Native people used other natural materials like porcupine quills, elk teeth, bone, bird or bear claws, and shells that were most often acquired through trade. The glass beads, easier and more flexible to use than unforgiving porcupine quills, quickly replaced other materials.

Not only were the beads more practical to use but the people who introduced them also brought their own influential style of decorative arts, opening new creative outlets for Native artisans. Scholars posit that Ursuline nuns of Italy, who arrived in northeastern Quebec as early as the seventeenth century, introduced silk embroidery and beadwork floral motifs to young Huron and Iroquois girls. From there, European needlework and Indigenous design forms gradually converged into designs that Native artisans fused and embellished.

Trade between and with Native peoples initiated a diffusion of cultures that enriched Native adornment practices. Prior to contact with non-Native peoples, American Indians established vital networks of trade. The evidence of these exchanges often surfaces in material culture. For instance, the Hohokam tribe, centered in present-day Arizona, traded seashells acquired from the Mojave, near the California border, for buffalo hides from various southern Plains tribes. From first contact with Europeans and their abundant trade goods, Native peoples made artistic use of these new materials to ornament their ritual objects and possessions. Examples of nineteenth-century Tlingit body armor, for instance, demonstrate the convergence of Northwest traditions with two other cultures: the crafted armor is covered in Chinese coins the Tlingit received in trade from Boston sea merchants in exchange for sea otter pelts.

16/2518

This lavishly beaded dress would have been worn by a young Sicangu Lakota girl on a very special occasion.

While glass beads from Europe became a prominent fixture in Native life and culture, beadwork grew into a distinctly Native art form, full of meaning. Native artisans developed intricate beaded designs to pass down stories and histories from generation to generation and reinforce tribal identity. It is a cherished practice that continues today. For instance, the elaborately beaded dresses that Plains women made— and still make and wear— became canvases upon which women expressed their creativity, marked significant events (such as marriage or a family member’s military service), and displayed family pride.

— BETHANY MONTAGANO

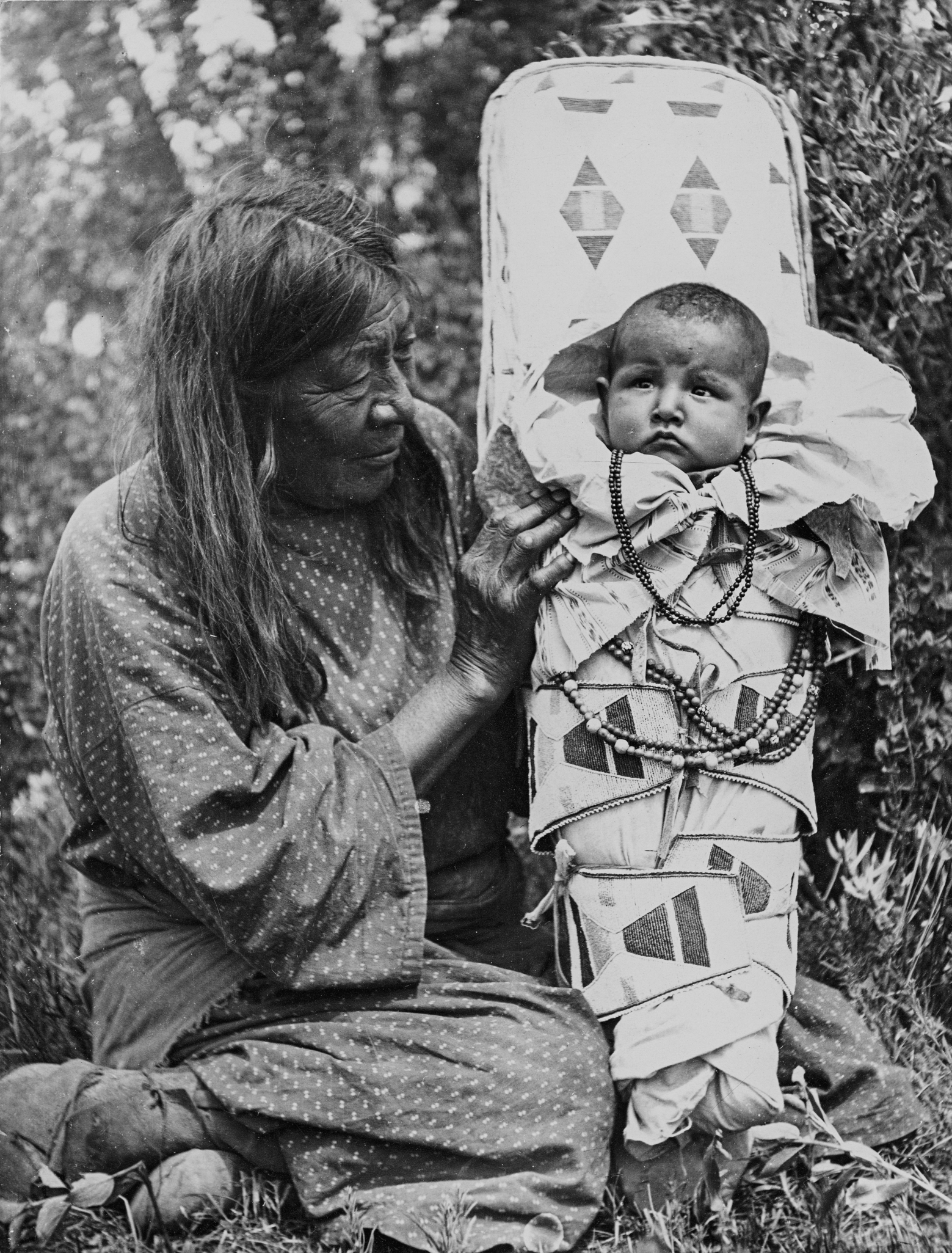

DO NATIVE AMERICAN PARENTS STILL PUT THEIR BABIES IN CRADLEBOARDS? ARE THE CRADLEBOARDS COMFORTABLE?

Yes. Many Native people still use cradleboards to secure their babies. While they may not be as common as they were two hundred years ago, you can still see children all over Indian Country wrapped in blankets and packed in their cradleboards. The cradleboards reflect a wide variety of tribal styles, and the materials used to make them range from wood, hide, and plant fibers to canvas and other fabrics. Most cradleboards have a protective arch made from a willow branch, reeds, or carved wood above the child’s head.

While not all tribes use them, those that do have a name for a cradleboard or baby carrier in their own language: pá̱ːjol for the Kiowa, tihkinaakani in the Myaamia language, and xe:q’ay’ for the Hupa. No Native American people call a cradleboard a papoose, however. So how did the word become associated with Native American baby carriers? The word papoose seems to have entered the English language around the 1630s, and comes from the Narragansett word papoos, meaning child, or a similar New England Algonquian word that literally means “very young.” Either way, papoos refers to the baby and not to the baby carrier. In 1643 Roger Williams, a Puritan who interacted with the Narragansett and Wampanoag peoples as a missionary, wrote A Key into the Language of America, which introduced and popularized several Algonquian words that were adopted into English. Among them were papoose, quahog, moccasin, and moose. Today the word papoose is often considered pejorative and stereotypical.

Crow woman and baby in a cradleboard, ca. 1900. P09352

Traditionally, cradleboards were highly utilitarian; a mother could carry a child on her back by a strap attached to the back of the cradleboard. The strap went across the mother’s upper chest and upper arms or across her forehead. This arrangement freed the mother’s hands to work. The mother and other family members could hang or prop up the cradleboard providing visual contact with the baby.

The cradleboard protects the infant physically and emotionally, allowing the baby to feel secure. Some cradleboards have bindings that attach the child directly to the backboard; other styles have a sack attached. The sacks (some tribes call them moss sacks because moss was used as a diapering material years ago) have binding to secure the infant. Some people use only the moss sacks, without a backboard. The flat back of the cradleboard keeps the infant’s spine aligned, and the binding helps strengthen the baby’s muscles by creating resistance when the baby pushes against it. Some types of cradleboard include additional cushions and supports for the crown of the head, neck, and feet. Most babies stay in cradleboards until they can walk and/or work their way out of them.

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people of the Northeast have always made cradleboards from wood and have carved beautiful designs on the backboards and protective wooden arches. They sometimes add paintings to enhance the carvings. Cradleboards made by many of the Plains tribes have wooden frames covered with soft hide and elaborately decorated with glass beads and porcupine quills. Other materials used in decoration are sequins, shells, silk- or cotton-thread embroidery, satin ribbon, metal tacks, and horsehair.

Some designs include sacred symbols and colors to bring the child good fortune and long life. Parents in many tribes saved the child’s umbilical cord and made it into an amulet, which was carried on the cradleboard as a toy, and kept throughout the person’s life. The Western Shoshone had two types of cradleboards made of woven willow reeds: the boat basket, which was used for newborns, and the hoop basket, used once the baby’s neck muscles were strong enough to hold up his or her head. A woven willow shade was added to the basket to protect the baby from the sun and keep the cradle upright if accidentally bumped. Some tribes, such as the Pomo of present-day California, used a sitting-style cradleboard, designed so that the child’s legs hung over the bottom edge. Today many of the woven cradleboards are covered with cloth, which is cool and also washable. A lot of time and effort are put into making a cradleboard, and its aesthetic beauty reflects the deep love parents and families have for their children.

— ALEXANDRA HARRIS AND MARY AHENAKEW

ARE INDIANS MORE PRONE TO CERTAIN DISEASES THAN THE GENERAL POPULATION? WHY?

Statistics show that considerable health disparities exist between American Indians and the general population of the United States. With a life expectancy of 71.1 years of age, Indians live on average 4.7 years less than the rest of the nation. Poverty, unhealthy eating habits, inadequate housing, poor sanitation, uneven quality of and access to medical care, and resistance to seeking treatment all contribute to the current health peril.

Indians face grim statistics for most diseases, with rates that are 4.9 times higher for liver disease and cirrhosis, more than 7 times higher for death due to alcoholism, 3 times higher for accidental deaths, and more than 6 times higher for tuberculosis, a disease often thought to be a plague of the past. Although drastic differences between Indians and the general population are evident for most diseases, the gap narrows for the leading causes of death, which for both groups are cardiovascular disease and malignant tumors. If there is one disease that Native Americans are more prone to than the rest of the population, it is adult-onset diabetes, and it is presently a threat that looms large.

Type 2 diabetes is on the rise for all Americans but significantly so for Native Americans, who have seen a 93 percent increase within their population since 1981 and currently suffer a diabetes death rate that is 3.5 times greater than the rest of the nation. One of the most important factors increasing the risk of diabetes for anyone is unhealthy weight, and, unfortunately, 37 percent of Native Americans are overweight, while 15 percent are obese. Through European contact, federally issued commodity foodstuffs, and poverty, contemporary Indians have developed a diet that is substantially different from that of their ancestors, one that often leads to the weight conditions conducive to diabetes.

The second critical factor that increases diabetes risk is genetics. Over centuries in a harsh and often unreliable land, Native Americans evolved metabolic genes that allowed them to efficiently store fat and survive famine. With the quantity and types of food available today, these genes are no longer beneficial. Nobody knows this better than the Tohono O’odham people of Arizona. Once a desert tribe whose meals were often few and far between, the Tohono O’odham now have the highest rates of diabetes in the world— approximately 50 percent of the tribe is afflicted. Ongoing medical research in the community is now establishing valuable knowledge about the genetic predisposition to diabetes. Meanwhile, the Tohono O’odham are joining tribes from across the country to actively confront the disease through diabetes prevention campaigns. As for all Americans and many other health concerns, regular exercise and a healthy diet are paramount in the battle against diabetes.

— JENNIFER ERDRICH

WHAT ARE THE RATES OF ALCOHOLISM, DRUG ADDICTION, AND SUICIDE AMONG AMERICAN INDIANS?

There is no doubt that alcohol abuse is a significant concern for Native American communities, but many misconceptions obscure the reality of this complicated situation. According to the most recent statistics published by Indian Health Service in Trends in Indian Health, 1998–1999 the alcoholism death rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives is more than seven times the rate for the general population of the United States. In addition, alcohol is implicated in three-fourths of all traumatic American Indian deaths. It is a major factor in the high rates of suicide, homicide, automobile accidents, crime, family abuse, and fetal alcohol syndrome in Native American communities. These numbers, however, do little to explain the history, the present reality, and the confusion over American Indians and alcohol.

Researchers have proposed different theories about why alcoholism is still a scourge to the Native American population. Historical explanations describe how past laws making it illegal for Indians to possess or consume alcohol led to a consumption pattern of binge drinking. For those less inclined to historical arguments, many researchers have sought a genetic explanation for the disease. Some studies have focused on two candidate genes associated with alcohol metabolism that sometimes have a different form in American Indians. To date, no report has conclusively confirmed that the gene variants do indeed cause American Indians to process alcohol any differently than the rest of the population or cause them to be more prone to alcoholism. Scientific literature is careful to state that there may be a link, but that important qualification is often overlooked. Meanwhile, the idea of possible genetic susceptibility can be misconstrued into myths of “genetic weakness” that misled both non-Indians and Indians themselves. Lost in the mythmaking is the fact that individual tolerance levels vary among individuals.

Amid the controversy and confusion, the risks and causes of alcoholism have yet to be clearly identified. Many focus on the critical role that socioeconomic, cultural, and psychological factors play in the disconcerting rates of Native American alcoholism. Poor education, alarming poverty, family and community instability, and low occupational status increase the prevalence of alcoholism in any family. Sadly, these conditions are all too real for many American Indians.

As for drug addiction and suicide, the rates are elevated in the Native American population as well. The drug-related death rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives is 65 percent higher than for the rest of the general population of the United States, while the suicide rate is 72 percent higher. Again, the historical and current causes of these perplexing and difficult situations must be considered just as seriously as the numbers themselves to better understand the existence of the disparities.

— JENNIFER ERDRICH

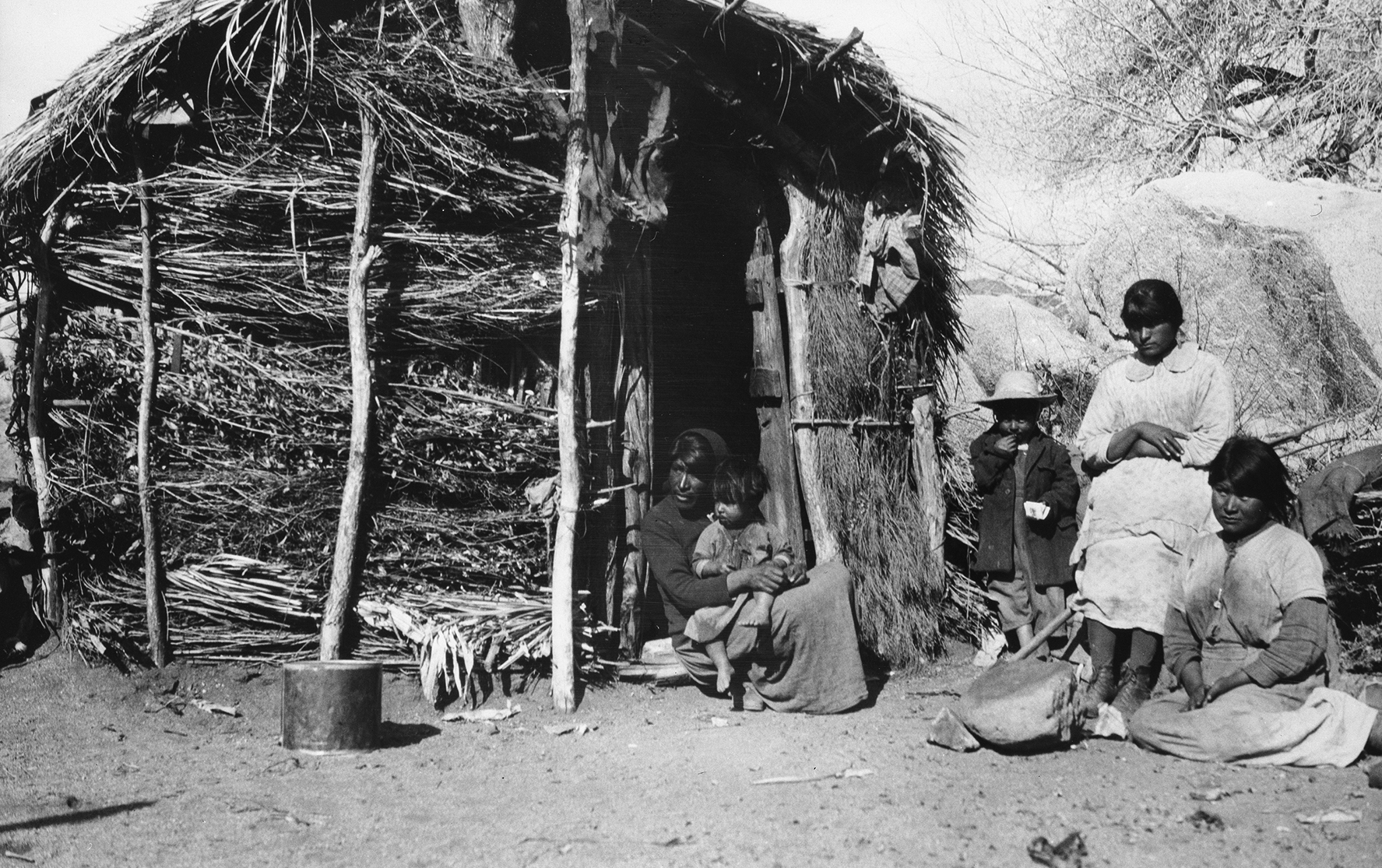

DO ALL INDIANS LIVE IN TIPIS?

Most American Indians live in contemporary homes, apartments, condos, and co-ops, just like every other citizen of the twenty-first century. Some Native people who live in modern homes do erect and use tipis in the summer for ceremonies and other community events. But most Indians in the Americas, even those who live in their community’s traditional dwellings, have never used tipis at all.

Tipis are the traditional homes of Plains Indians, but in other regions of the Western Hemisphere Native people lived in many different kinds of dwellings. Whether a tribe lived in a buffalo-hide tipi, an adobe hogan (dwellings made of adobe and supported by rocks or timbers), a birch-bark wigwam, or an igloo made of ice, the home’s structure and materials were suited to each tribe’s needs and environment. Some Diné (Navajo) people, for example, still live in hogans because the structures are well adapted to the desert, which can be extremely hot during the day and cold at night. During the day the hogan remains cool inside as the adobe absorbs the sun’s heat. At night the structure releases the heat, keeping everyone inside comfortable.

The Great Plains at one time sustained millions of buffalo, and the Plains Indians depended almost entirely on the buffalo for their basic needs— including shelter. Their larger tipis were each made of as many as eighteen buffalo hides. Pueblo people of the Southwest live in homes made of adobe, which were the first apartment-style structures in North America.

American Indians have traditionally lived in structures that took best advantage of their individual resources, environment, and location. Inuit people constructed domed structures called igloos, which were made from blocks of snow. The coastal Inuit used igloos as temporary hunting shelters, but the interior Inuit lived in them year-round. An igloo could be built in about an hour and easily repaired or replaced. They are still used as temporary hunting shelters.

Photo by Edward H. Davis. N24649

A Paipai mother and four children sit outside a house made with brush siding, 1926. Baja, California.

The people of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy built long houses made from logs, saplings, and bark, all of which were abundant in their forested environment. Each long house could shelter several families and, if needed, could be expanded to accommodate more people. During World War II, when U.S. troops needed inexpensive and easily constructed housing, military architects modeled what came to be known as Quonset huts on the long house design. Today not only long houses but also many other traditional Native dwellings are used primarily as places for social and ceremonial gatherings.

— STEPHANIE BETANCOURT