RACHEL WILLIAMS

Photo: S. Mizelle

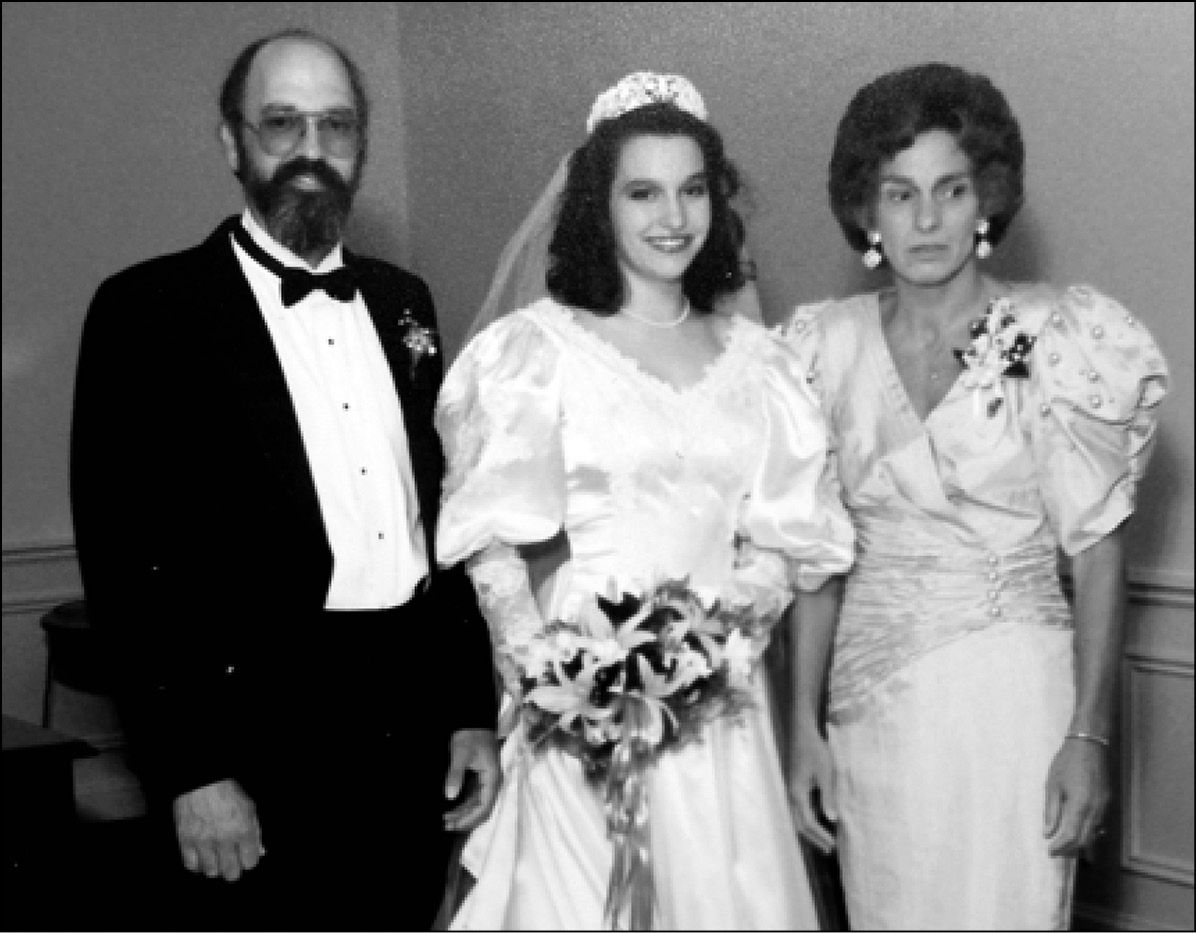

The picture of my mother, father, and I was taken in the heart of the South at my first wedding in June 1990. I am nineteen and my mother is forty-six — only four years older than I am today. My mother is wearing a peach taffeta cocktail dress and I look like an upside down muffin made of white Italian silk covered in seed pearl sprinkles. We are over-made, over-sprayed extras from Designing Women.

My father, present and relaxed, is oblivious to the undercurrent of feminine turmoil and wears a crooked, confident smile. My mother frowns and looks beyond the lens of the camera. Clearly, she would rather be doing something other than posing for Mr. Mizelle who is the only photographer in our tiny town of ten thousand. Mr. Mizelle wears slacks and white socks with his black shoes, and he still wears a pompadour. His son Mike was the first boy I ever French-kissed. He is not the boy I am marrying, but he is at the wedding like everyone else I have ever dated or known.

My face is plastered with a smile that does not engage the muscles around my eyes. I didn’t want to get married. In February, I had tried to call it off. We were in the car and my fiancé was nonplussed as he stopped and started on the jammed freeway. He told me to keep the ring and think about it. I looked out the window and counted the orange traffic drums in the stifling silence. My finger felt like it was swelling around the white and gold filigree engagement ring, a treasured antique in his family. No amount of soapy water would ever help me get it off again. He knew that I would give in and marry him if he waited me out. He knew my resistance would pass. He was right. In the end, my need to make everyone happy overruled my gut-wrenching, sweaty-sheets-in-the-middle-of-the-night fear that I was doing the wrong thing. He was a nice guy after all. What more did I want?

Twenty minutes before the photograph was taken, my mother had been having a meltdown over hatpins and some ham biscuits that had not arrived at the reception on time. The annoyance is still on her face. Little did we know, she was in her first month of full-blown menopause. Now, twenty-three years later, I am perimenopausal and I recognize my mother’s struggle.

The women on my maternal side start their periods late and stop bleeding early. My aunt was in menopause at thirty-eight. Our hair greys prematurely and we all get a “cute” little bulge right below our belly buttons. The only upside is that we become voluptuous. We finally grow the bosoms we had always tried to fake with padding and underwire. Our hips begin to resemble pumpkins. We look for undergarments with Lycra panels stitched in the front and support hose with built-in girdles. The extra weight that comes with menopause gives us a swagger that looks best in low heels and belted full skirts with low cut tops, the kind of outfit that square dancers on Hee Haw wear.

My mother’s worst moment with me happened the previous September before my wedding. I had called her from my crappy apartment during my freshman year to explain that I might not return home from college until Thanksgiving. There was a long pause. I listened to the static as I twisted the telephone cord waiting for her response. I examined the peeling plaster ceiling. I could feel her rage building through the receiver. She drew in a long breath and then unleashed a blast of hysteria the likes of which I had never witnessed while I was living under her roof. It culminated in, “You are never coming home again, are you?” This shrill, guilt-laden, grief-stricken accusation was my mother’s way of saying she missed me. It was her way of saying I was ungrateful.

Looking back, I realize my mother had been slowly unraveling since my first year of high school. She never slept. She was a bundle of nervous energy. She developed acne. She dismissively attributed her symptoms to too much caffeine or red wine. During these years, my father would do anything to avoid the passive-aggressive torrent of anguish and anxiety that had become my mother. He initiated a new tradition of month-long camping trips, and when he was home, he spent his Saturdays sailing his little boat up and down the river and working in the garden. My brother, the good child, had already fled to college. And I made my parents’ life hell. I took some pleasure in heightening my mother’s emotional state on a daily basis by letting her know, with the mouth of a sailor, that I felt tortured by her constant maternal scrutiny.

I know now that at the wedding, there was more bothering my mother than hatpins and ham. There were the usual crushing pressures of hosting a wedding, but added to this was our “mixed” marriage. We were from St. Peter’s, the Episcopal church that was opened in 1822 and remained active thanks to old money and the pecking order that is pervasive in small towns. But I was marrying into Baptists — the old-fashioned kind of Baptists who do not drink and expect their wives to obey them. And I had not finished college yet.

But there was still one more issue, one I didn’t learn about until years later, when my mother confessed that on the day of my wedding, she thought she was pregnant. I don’t know when her period actually stopped. But I do know that on the day I got married she had chosen the implausible idea of pregnancy at forty-six over the plausible idea she had finally entered menopause. Magical thinking was one of my mother’s special skills.

My conception in 1972 had been an accident. My mother, a trained nurse, mistook breastfeeding for birth control. I can’t believe that she trusted this bit of family planning folklore. Her first baby, my brother, was only nine months old when I was conceived. Then or now, she would have had one choice. My father was pro-life. Only a year before, he had tried to convince her to join his empty-nest scheme of adopting a child from Korea. He would have welcomed another child.

Perhaps she was so angry after my wedding and after learning the truth, because she felt her uterus had betrayed her. Once again, she’d fallen victim to her body’s deception. She was no longer fertile. Her children had left. She had finally crossed over.

The summer following my wedding she began hormone replacement therapy. This improved her mood and her skin. If she was honest, she would say her life became easier once her nest was empty. She reverted back to the sweet woman I knew from my childhood. Post-menopause, she grew deeply engaged in her job, received a promotion and took her hobbies of sunbathing and basketball watching to new levels. She stopped cooking from scratch and began to serve my father meals made with boxed and frozen ingredients. A year later, she discontinued HRT when studies appeared that made her fearful of its effects. Meanwhile, my interest in my mother’s emotional state waned and she and my father receded into the background of my self-centred twenty-something life. At some point, menopause was just a private fact of her new identity.

Now that I am perimenopausal, I too am sometimes anxious and can’t sleep. Sometimes I feel manic. I have irrational bouts of quiet hysteria triggered by insignificant incidents like unfolded laundry and annoying calls from my ex-husband. I yell at my children. I have night sweats and hot flashes and my period comes and goes without any regard for the calendar, my sex life, or my schedule. Slowly, my body is transforming. Like my mother, I have a deep crease between my eyebrows. My eyelids look like fine crepe paper. There is a growing bulge beneath my belly button.

And I await my voluptuous curves.