6

Benchmarking

Patrizia Garengo

6.1. Introduction

Benchmarking emerges as a structured comparison, based on the continuous research and application of the most advanced methodologies, aimed at achieving superior competitive results (Watson, 1993). It is recognized as a particularly relevant approach in quality management, both as a tool that can facilitate the improvement of management practices and as a management technique that can help define the strategic positioning of an organization (Pham, Tisak & Williamson, 2012).

The term benchmark (or comparison parameter) is originally used in land surveying to indicate a reference sign to compare differences in level height or direction to. In the 1980s, the term benchmark was used in the industry to indicate excellent performances and managerial practices organizations can compare with in order to identify possible improvement actions. Thus, benchmarking is identified as the set of observation and comparison activities between benchmark and current practices and/or performances undertaken by organizations to encourage improvements. It is worth noting that this is not a comparison bound to imitate market leaders’ strategies or practices, but a research used to identify those elements characterizing the success of excellent organizations; these can be later converted into strategic and/or operating improvements for other companies, even in different sectors.

A project of effective and comprehensive benchmarking is developed following a structured process that allows the continuous research, analysis and adoption of excellent practices, a concept often summarized with the Japanese term “dantotsu” (which literally means the search for the “best of the best”).

6.2. Origins and Evolution of the Benchmarking Concept

Benchmarking, intended as the process that facilitates the improvement of management practices, began to spread in the first half of the 1980s, in response to a greater competition, a more dynamic context and to the crisis that significantly struck large Western companies in those years. To face the rapid increase in the performance gap compared to some competitors, it became essential to introduce innovative practices capable of improving business processes quickly, reducing costs, and increasing both performance and products and services quality. Many of the US multinationals, such as Xerox, IBM, Ford, Compaq and Digital, started important innovation processes based on the observation of the managerial practices of excellent organizations.

Xerox Corporation acted as pioneer and quickly became a symbol for benchmarking. To contrast the gradual decrease in profitability and market share caused by the strong Japanese competition, the company started several benchmarking projects. In 1979, it started to analyze the costs of the various production units; a careful comparison between the copiers produced by the Japanese affiliate Fuji-Xerox and those produced by other Japanese companies, highlighted that competitors were selling machines at a price that matched Xerox manufacturing price. David Kearns and Robert Camp, CEO and Logistics Manager of the company, respectively, following the observation of organizational structures adopted by some successful enterprises, introduced radical changes in critical process handling procedures, modified some manufacturing components and managed to reduce production costs. After a few years, the company management decided to extend benchmarking to all business units and all cost centers. The benchmarking process was soon recognized as one of the key components toward the achievement of a higher quality in all processes and products. With the introduction of benchmarking, Xerox changed its business model and redefined its mission and organizational structure, moving from a functional logic to a process logic. The experience of Xerox was published by Robert Camp (1989), in the text Benchmarking. The search for Industry Best Practices that lead to superior Performance, which soon became a best seller worldwide and from which a rich body of literature and interesting managerial experiences emerged.

As documented by Camp (1989), in the light of Xerox experience and its subsequent applications, it is possible to identify an evolutionary path of the benchmarking concept comprising five generations (Watson, 2007).

The first generation, called Reverse Engineering and product competitive analysis, compares the features, functionality and performance of a company’s products and services with similar products and services produced by competitors. The characterizing aspects of this methodology, such as the dismantling of a product, the assessment and comparison of its technical features, act as an important incentive for improvement and even today, they are used by many organizations as a learning resource.

The second generation, competitive benchmarking, reaches maturity in the 1976–1986 decade and acts as an extension of competitive analysis and market research. Competitive benchmarking aims at identifying the actions taken by competitors to gain competitive advantage and carefully analyzes strategic decisions and investments in products and services that define the superior performance of some leading companies. Its analysis goes beyond comparisons only focused on products to include comparisons between internal and competitors’ processes, soon becoming one of the tools used in strategic planning process.

The third generation, called process benchmarking, spread over the period 1982–1988, thanks to the start of some major improvement projects promoted by a group of companies’ leaders in quality management. Process comparison spread quickly because of its highlighting interesting learning opportunities and the possibility of involving companies operating in different sectors, thus gaining a greater information sharing compared to projects involving only competitors. For example, to optimize the order fulfillment process, Xerox analyzed the process handling procedure in organizations operating in different sectors and found an analogy between the shipment of copiers and the shipping process of boots and other fishing equipment developed by L.L. Bean. A thorough study of the fulfillment of L.L. Bean order process allowed Xerox to identify important improvements in its order fulfillment process.

In the fourth generation, strategic benchmarking is introduced as a systematic process to evaluate alternatives, implement strategies, and improve performance through the understanding and adapting of other organizations’ successful strategies. Strategic benchmarking differs from process benchmarking especially for the entity and depth of companies’ commitment; together the two kinds of benchmarking represent the heart of scientific studies on the subject.

The latest generation, global benchmarking, extends the geographic boundaries of the analysis and implies the overcoming of existing distinctions between companies in terms of international trade, culture and processes. It includes the comparison of generic processes, the use of the Net to view and gather information or to find benchmarking partners and the global sharing of study results to maximize learning.

In the current competitive environment, all illustrated types coexist and are adopted by organizations to meet the different needs. However, a prevailing application of process benchmarking is clear, while the number of companies using it systematically in strategic planning is still limited. Benchmarking is used as a management tool whose importance in the pursuit of managerial excellence is formally recognized not only by companies that have experimented its use but also by the institutions chairing the main Quality Award. A particularly positive boost is linked to the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, which specifically includes the use of benchmarking and makes explicit reference to it more than 200 times, already in the 1994 criteria.

6.3. Characteristics of the Benchmarking Process

The benchmarking process is characterized by three key aspects: comparison with the external context, learning and improvement.

The launch of a benchmarking project requires the understanding that internal resources alone cannot always offer excellent solutions, but a constant and systematic assessment of external solutions toward best business practices is required. The comparison with the external context can be used to find excellent alternatives to establish internal procedures, through the study of competitor companies but also engaging different types of businesses whether large or small, public, or private, within a national or international context.

It is widely recognized that encouraging individuals to look outside and start analyses and comparisons with internal procedures and/or strategies facilitates individual and organizational learning as well as the generation of new ideas. All activities of planning and analysis characterizing the benchmarking experience help improve the processes of target setting and the analysis of results. In the benchmarking process, goals are not set following an incremental logic compared to the past but looking at excellent references; the selected reference itself (the benchmark) is not unchangeable, but must be continually updated to adapt to the rapid changes in the economic environment. Thanks to the analysis, understanding, and comparison, the benchmarking process, if properly conducted, is considered capable of promoting both operational and strategic improvements with a consequent increase in performance.

The effectiveness of a benchmarking project implies the adoption of a default method, which must be chosen according to the objectives of the project itself and the available resources. The different types of benchmarking, some of which anticipated in the description of the concept evolution, will be analyzed below. In general terms, it is important to highlight that the general benchmarking process can be divided into two major subprocesses: performance benchmarking which allows identifying critical processes open to improvement and best practice benchmarking aimed at defining the path to improve the corresponding management practices.

A comprehensive benchmarking project is not limited to the measurement of performance gaps; this measurement is only a starting point for the identification of best practices that make the pursuit of excellence possible (Bititci Firat Garengo, 2013). The determiners at the origin of higher performances are then sought by measuring, comparing and analyzing the activities of different organizations, or by adopting reference operating models showing good management practices valid for a number of companies (Mi Dahlgaard-Park & Cocks, 2012). The synergistic, positive and integration-promoting relationship between practice benchmarking and performance measurement is also openly contemplated by the Quality Awards, which, for example, follow the EFQM model, such as the Italian Quality Award.

6.4. The Approaches to Benchmarking

The description of the benchmarking concept evolution has highlighted different classifications. Worth noting is the famous taxonomy proposed by Camp (1989) which identifies four types of benchmarking based on the source of data: internal, competitive, functional and generic.

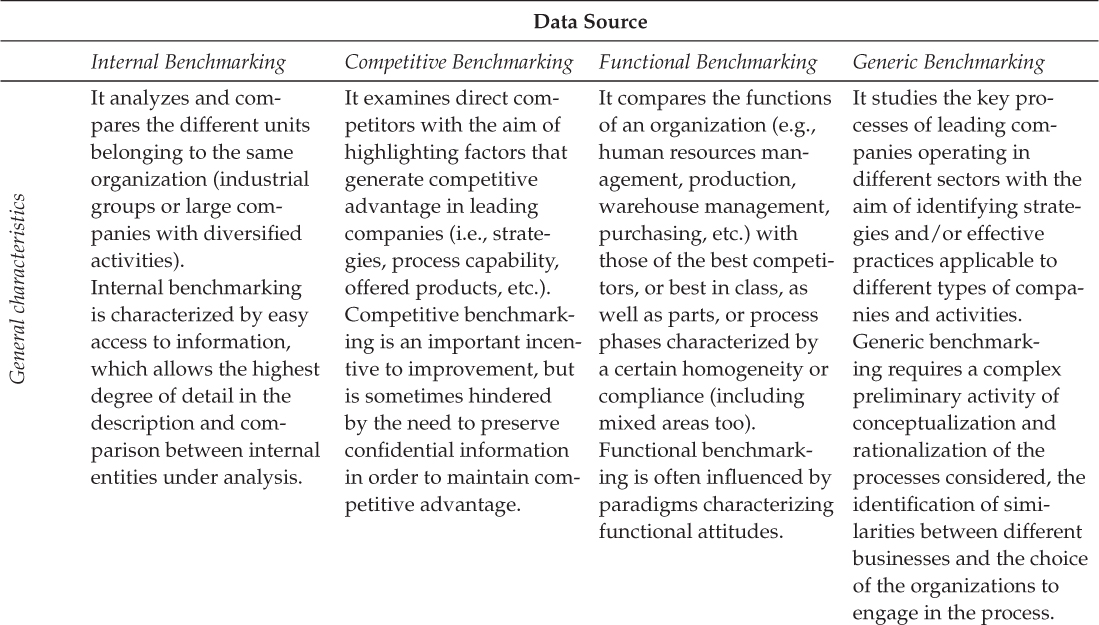

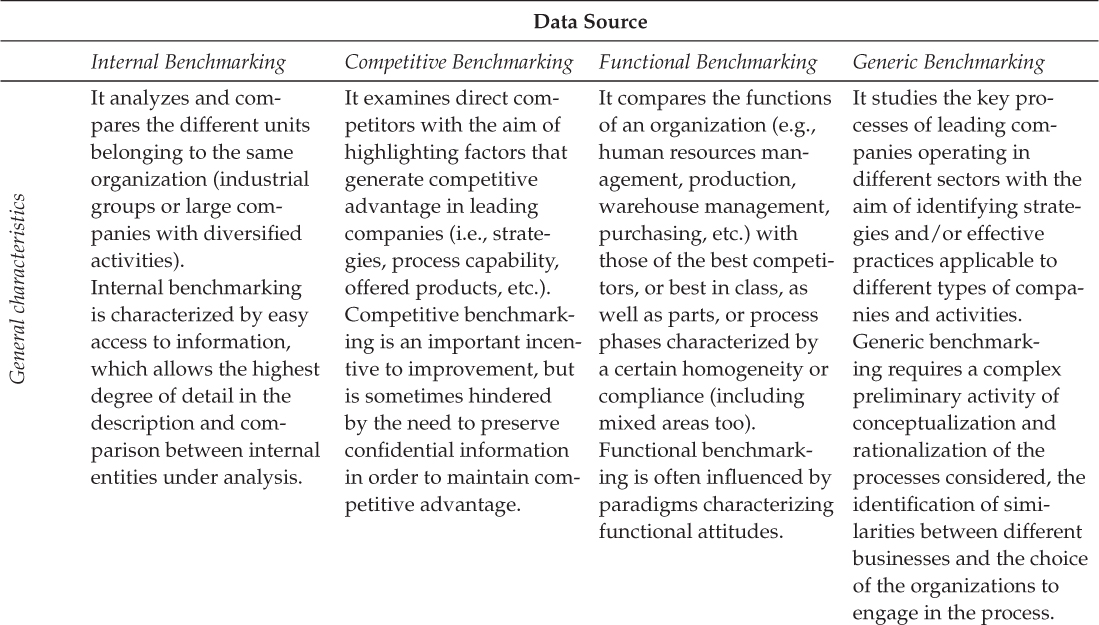

Considering both the level of analysis and data source, Watson (2007) extends Camp’s analysis and identifies eight types of benchmarking, which distinguish between strategic aspects and operational aspects analysis and comparison (Fig. 6.1). In the first case, benchmarking is a tool that can make a valuable contribution in planning, programming and control of results and in the review of the performance measures of the entire company or some of the strategic business areas that ensure a particular competitive advantage. Operational benchmarking concerns instead operational processes or procedures and aims at increasing productivity in terms of routine task effectiveness, efficiency, or cost-effectiveness; it is recognized as a technique useful in the realization of business process reengineering (BPR) tools, whose use often precedes or accompanies BPR interventions. Subject of the analysis are operational procedures, equipment, skills and methodologies leading to improved performances measured in terms of output volumes, defects, unit cost of products, etc. For example, an operational benchmarking may comprise a study and comparison between the different production methods used by a group of leading companies with the goal of identifying the method which minimizes unit costs, ensuring compliance with quality standard and expected production volumes at the same time.

Fig. 6.1: Data Sources and Analysis Level. Source: Adapted from Watson (2007).

Besides data sources and analysis level, a benchmarking study requires an accurate definition of two key dimensions: the object of analysis and the methodology to be adopted when undertaking a benchmarking project (Garengo, Biazzo, Simonetti, & Bernardil, 2005). The joint use of these two dimensions, which will be analyzed in the Sections 6.5 and 6.6, allows to identify four additional types of benchmarking: performance benchmarking, practice benchmarking, synthetic benchmarking and analytical benchmarking.

6.5. The Benchmarking Object

Benchmarking object can be performances, intended as the results (or outcomes) of a process, or practices defined as organizational solutions structured to manage or link activities.

Performance benchmarking focuses on quantitative results, also intended in organizational sense. It is used not only to compare the performance of different companies (Bititci, Firat, & Garengo, 2013) but also to study key areas within the same organization; in the latter case, it is particularly useful if data collected are used as a diagnostic tool aimed at highlighting those areas where action is needed.

The outcome measures that are considered particularly significant target the entire spectrum of critical business processes, the characteristics and the efficiency and effectiveness level achieved (i.e., time, cost, quality, productivity, flexibility, customer satisfaction, etc.). The reference used as a benchmark can be a goal identified during planning, the best performance of an internal procedure or a leader company. The information used may be collected using sector performance indicators in the public domain or participating in benchmarking projects involving a group of companies willing to share information on the achieved results. In both cases, performance benchmarking responds to the widespread desire to collect information on the positioning within a sector or a competitive context in a simple and fast way.

However, as illustrated in Section 6.4, performance benchmarking is just the beginning of a true comprehensive benchmarking process; highlighting the existence of gaps in the current and expected performance allows to locate problems and difficulties, but it does not bring to light the causes of these gaps, nor suggests actions on how to fill them. Performance comparison quantitatively detects phenomena and captures the attention of the interested parties, but becomes an effective tool only if it is recognized that the work starts right from the results of this analysis. The weakness of this approach appears therefore in the difficulty of representing a basis for learning and change. The improvement action suggested by an effective benchmarking process only becomes possible if processes that generate performance are investigated.

Practice benchmarking is recognized as a key tool in change management since it encourages the identification of practices behind the best performances, suggesting them as a reference for improvement actions (De Castro & Frazzon, 2017; Garengo et al., 2005).

The analysis units are practices, intended as “organizational solutions structured so as to manage individual assets or link different activities, whether sequential or reciprocal” (Beretta, Dossi, & Grove, 1998). Such practices determine the method for managing processes defined as “a set of activities, typically belonging to different professions skills, linked by significant flows of information, whose combination leads to a significant output for the whole enterprise” (Dossi, 2001). Practices can be analyzed within processes belonging to specific organizational units, cross-functional processes and inter-organizational processes (Bititci, Garengo, Ates, & Nudurupati, 2015).

The development of a benchmarking project on practices lends itself to be used by an organization to increase the knowledge on its own processes and compare its way of acting with that of other organizations or other similar processes within the same organization. Companies that have a well-defined mission, a set of clear objectives and, most importantly, a clear priority scale, feel the need to implement a systematic comparison that allows to locate and refine business processes contributing to the achievement of the objectives. The analysis can consider both primary and support processes such as, the order collection and fulfillment, billing, debt collection, etc. Learning and improvement may also occur when comparing processes of companies operating in different sectors. For example, in any organization, there are procedures and practices for credit recovery that can be detected and measured. An organization interested in the improvement of this process could analyze practices of companies with an excellent reputation in the management of debt collection methods, or specialized in the provision of this service, compare its own practices with those from the surveyed firms and then identify necessary actions to improve the management under analysis.

6.6. Methodology for the Implementation of the Benchmarking Process

General benchmarking approaches may in some cases generate positive changes, but the real learning develops only by following a well-defined and consistently applied process. The realization of a benchmarking project requires the implementation of a structured comparison based on a predefined methodology suitable in driving the collection and analysis of the necessary information. Data collection should be handled accurately, according to the project guidelines and objectives; results arising from the comparison and analysis will then be evaluated taking into account the specific features of each organization involved, to identify improvement actions that are realistic and consistent with the company reality. As pointed out earlier, the launch of a benchmarking project does not mean collecting information to imitate excellent companies, with the consequent risk of reproducing, when slavishly replicating objectives, practices, or procedures adopted by others without considering the strategic and operational coherence of the proposed changes.

To promote the effective realization of a benchmarking project, over the years literature and managerial practice have developed several guidelines and methodologies highlighting the presence of two possible approaches. The entire process can be carried out using simple tools, generating a process of synthetic benchmarking, or more complex methods which anticipate an analytic benchmarking. The two types are described subsequent paragraphs.

Synthetic benchmarking is characterized by a marked simplicity and recognized efficacy determined by the use of scorecards, which synthesize knowledge and simplify analysis and comparison activities. Its application, on the one hand, supports the identification of problem areas, highlighting gaps between the current and expected performance and, on the other hand, provides useful information for the development of action plans designed to improve performance. The use of scorecards allows the company involved to assess its position (in relation to practices codified within the instrument), highlights the possible gap with excellent practices in a specific context and identifies, if necessary, a possible improvement path (Bititci et al., 2015).

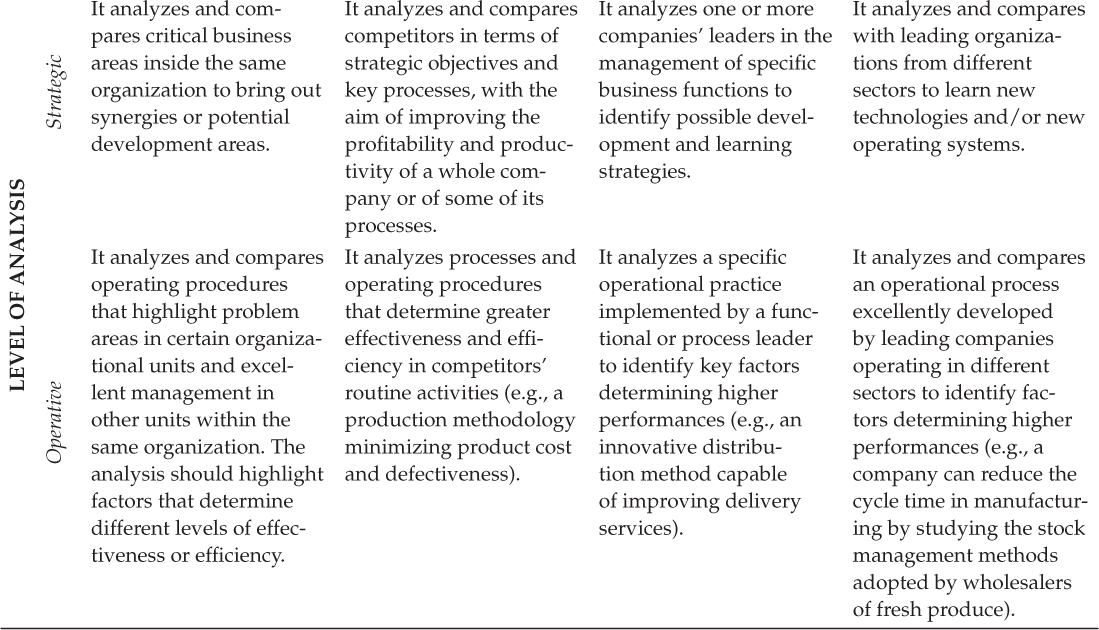

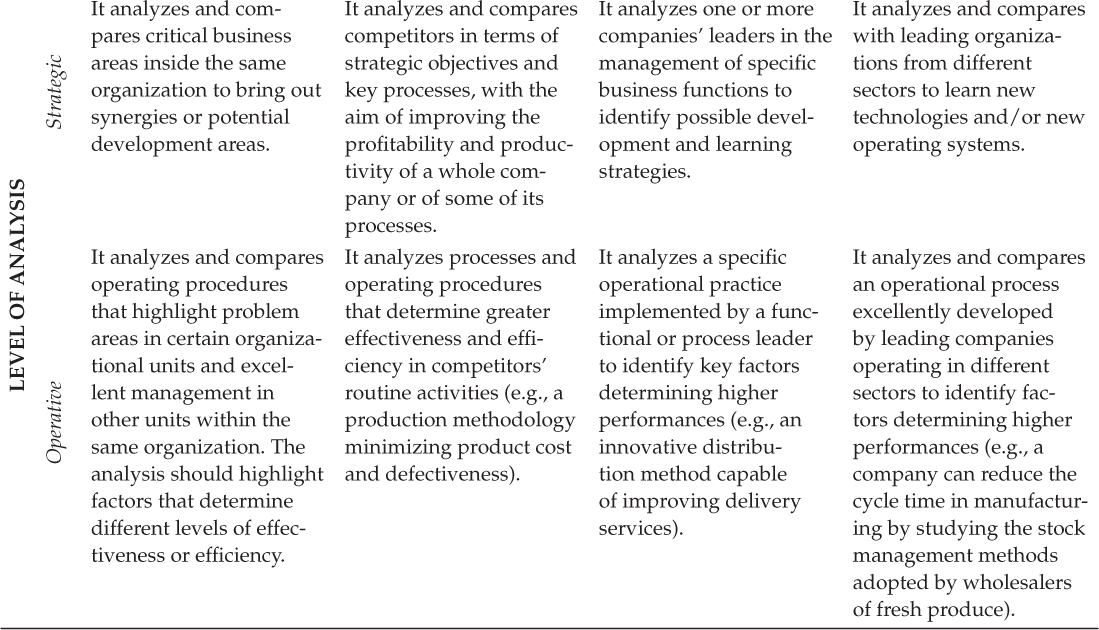

Fig. 6.2 shows an example of a scorecard drawn from an assessment tool for management practices (Garengo et al., 2005); the reported score card refers to the Price evaluation area of the Marketing process and it highlights four levels of possible practices also indicating the excellent practice (Level 4 – Best Practices). The use of the scorecard allows the company to evaluate the current practice, identify its position, and implicitly suggests the path to bridge the gap between current practice and best practice, which becomes immediately clear when filling out the questionnaire. On completion of the analysis, it will be possible to compare the results with other companies’ and identify suitable action plans with appropriate improvement activities.

Synthetic benchmarking is a simple methodology which can be used for a deep self-analysis of the majority of processes, even without specific internal competence and the support of external evaluators. Particular attention deserves the numerous models proposed for the evaluation of product innovation management; these models support in a simple and efficient way the diagnostic needs of enterprises through the use of mechanisms which stimulate critical reflection on current management practices. Furthermore, they are recognized as a useful tool to support improvement planning in the management of the innovation process.

Synthetic benchmarking is also recognized as a particularly useful approach in analyzing key processes or to support the analysis of the main management areas of small and medium-sized enterprises. With synthetic benchmarking these will have a clear, simple and exhaustive instrument to identify areas to focus on, avoiding resources being wasted in the want to improve everything indiscriminately, and also promoting the achievement of superior results.

The main difficulty in synthetic benchmarking is design, usually taken care of by external institutions who have the daunting task of synthesizing heterogeneous knowledge in comprehensive and unambiguous scorecards that can be used by multiple organizations at the same time. Particularly critical is the choice of processes to examine and the definition of best practices; on the one hand, these should refer to the concept of universality, and, on the other, there is no practical possibility of including in a benchmarking study all the subjects adopting excellent practices (Beretta et al., 1998). Best practices are those that have demonstrated excellence traits among all those subject to benchmarking according to certain performance assessment criteria. As it is not possible to find the absolute excellence worldwide, a best practice is by nature a relative one. The only way to maximize reliability and the correct use of the instrument is to define evaluation criteria clearly and objectively, referring to a predetermined and limited scope of analysis and widely documenting the reasons leading to the adoption of such criteria.

Fig. 6.2: Scorecard Relative to the “Price Strategy” Which Is Part of the Marketing Process.

A further difficulty in the definition of best practices lies in the nonrealistic possibility of defining absolute best practices; it is in fact very difficult to state that there is an excellent way to carry out a specific operation, since a practice recognized as excellent by one organization is not necessarily so for another. The clarification of situational factors would allow considering the originality of individual cases, would increase the quality of assessments and avoid the occurrence of occasionally inconsistent results. However, despite the acknowledged importance of situational factors, synthetic benchmarking tools often do not provide for their definition and analysis to prevent a heavy evaluation system which, by definition, should be characterized by ease of understanding and use.

Analytical benchmarking requires the adoption of a systematic and continuous process developed following a thorough investigation, based on articulated models and with a well-defined structure. These models do not incorporate the necessary knowledge for comparisons but accurately guide the definition and collection of the necessary information. Analytical benchmarking supports the creation of a constant study, strictly based on the use of regularly updated information to respond to the continuous context changes.

The required diagnostic and evaluation processes are divided into several phases and has a high level of complexity, given the rigor with which the main steps and substeps must be followed. Analytical benchmarking, focused on critical functions or processes, requires a great employment of resources in terms of time, economic resources and professional skills, but allows managers, consultants and employees of a company to clearly grasp both the evolution of the internal context and internal environment changes.

An example of analytical benchmarking is well summarized in the five-step model proposed by Camp (1995) beginning with planning and progressing through the analysis, integration and action, ending with maturity.

An analytical benchmarking survey is definitely more complex than its previous one and more costly in terms of required resources. The phases of the adopted model should be strictly followed in the order described, and sometimes they involve the contribution of external professionals to ensure a smooth progress. The successful implementation of this instrument requires not only the involvement of management but also the active participation of staff involved in all activities under consideration, since the contribution of experts in the specific operations is essential. If the analytical benchmarking study is conducted and completed in compliance with the procedures described in the model, a large amount of data and information is made available to the company, which will benefit from its efforts through valuable suggestions or real guidelines to achieve excellence levels in different areas of the organization.

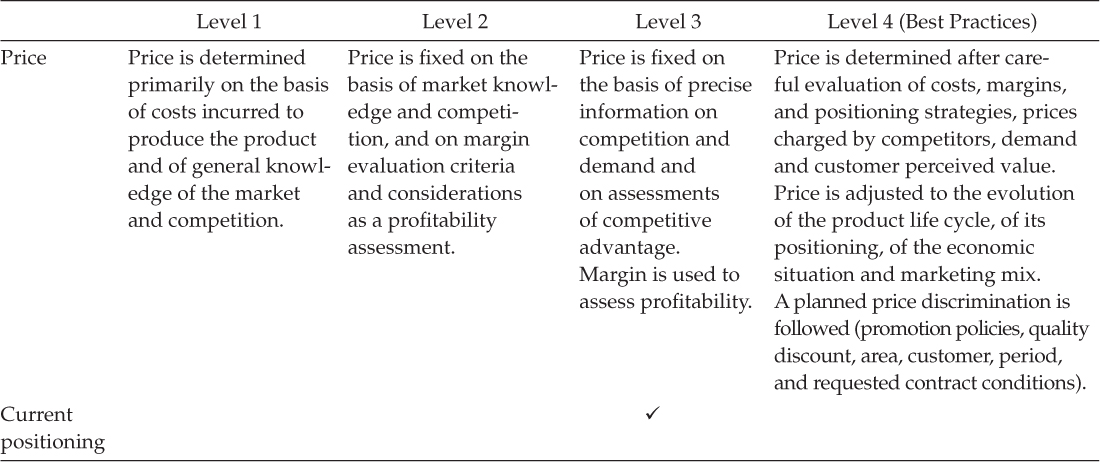

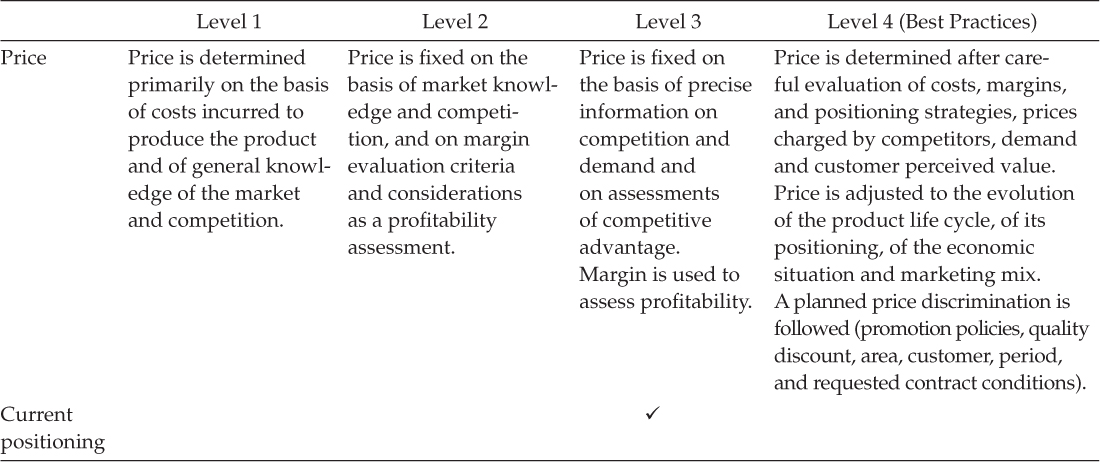

Several authors approached this subject by proposing texts and publications that analyze the steps above and develop alternative solutions to the model developed by Camp (1995). In this literature area, the use of evolutionary-cyclic logics quoted in the Deming wheel and summarized with PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act) becomes relevant. The American Productivity and Quality Center (APQC) and the International Benchmarking Clearinghouse, a subsidiary of APQC, have proposed a parallel between the Deming model and a possible benchmarking approach, highlighting the thematic continuity with Total Quality Management concepts. Benchmarking is therefore a cyclic process resulting from the more famous Deming cycle, where continuous improvement is linked to constant assessment against best-in-class and is divided into planning (Plan), data collection (Do), data control/comparison (Check) and finally a phase of action aimed at improvement and, consequently, recalibration (Act) (see Fig. 6.3).

Fig. 6.3 shows the PDCA cycle as the succession of operational actions describing the evolution of the benchmarking process into the four phases Plan, Do, Check, Act described as follows:

Plan. Any quality improvement process starts with a Plan, which may comprise both a large-scale review of company business, or a departmental project limited to the optimization of a given workflow. Regardless of its scope, the process must undergo constant checks and requires careful selection and definition of the processes to study, the identification of the measures to be used, and the evaluation and choice of companies.

Do. After defining the study project, it is necessary to identify a reference system to assess its effectiveness, thus starting the data collection phase from the different partners, as planned in the previous step. This involves the examination of all the available information on how the chosen process is performed in the target companies. During this phase, it is important to gather all possible information before applying directly to these companies, to facilitate an effective subsequent collection supported by telephone inquiries, written questionnaires and surveys.

Check. Action is followed by the examination of the information, to check if the plan and changes implemented until then have generated the expected improvement. The analysis focuses on the determination of the differences in performance between companies and the identification of process driving factors and practices that determine the best performances of leading companies. Performance quantification is useful to better understand the processes of a company by comparing later the performance gap between internal and external processes, and it should be possible to identify the gap between real and ideal situation.

Act. The last step consists in the adaptation, improvement and implementation of the appropriate driving factors following the logic of continuous improvement. Data may indicate the need to start a second PDCA cycle changing variables, or simply the convenience to stay on the achieved position, standardizing the existing process.

Fig. 6.3: The PDCA Cycle and the Benchmarking Process.

The Deming cycle is not the only possible model; however, one of its main advantages is determined by the use of themes and concepts already known in quality management. On the one hand, the described approach responds to the quality requirement of adopting planned operating mode and resources, as required by the process, and, on the other hand, the need for appropriate feedback and insights as a basis to identify and implement continuous process improvement. It is also worth emphasizing that the proposed approach is a general one and can be used in very different companies. The four phases described above require, in fact, a subsequent separate analysis, which gives rise to the subphases that will become the true operative steps of a benchmarking process capable of responding to the needs of the individual companies involved.

References

Beretta, S., Dossi, A., & Grove, H. (1998). Methodological strategies for benchmarking accounting processes. Benchmarking for Quality Management & Technology, 5(3), 165–183.

Bititci, U. S., Firat, S. U. O., & Garengo, P. (2013). How to compare performances of firms operating in different sectors? Production Planning and Control, 24(12), 1032–1049.

Bititci, U. S., Garengo, P., Ates, A., & Nudurupati, S. S. (2015). Value of maturity models in performance measurement. International Journal of Production Research, 53(10), 3062–3085.

Camp, R. (1989). Benchmarking, the search for industry best Practices that lead to superior performance. Milwaukee, WI: ASQC Quality Press.

Camp, R. (1995). Business process Benchmarking. Finding and implementing best practices. ASQC Quality Press.

De Castro, V. F., & Frazzon, E. M. (2017). Benchmarking of best practices: An overview of the academic literature. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 24(3), 750–774.

Dossi, A. (2001). I processi aziendali: profili di misurazione e controllo. Milan: Egea.

Freytag, V., & Hollensen, S. (2001). The process of benchmarking, benchlearning and benchaction. The TQM Magazine, 13(1), 25–33.

Garengo, P., Biazzo, S., Simonetti, A., & Bernardi, G. (2005). A benchmarking tool for organizational development in SMEs. TQM Magazine, 17(5), 440–455.

Mai T., Pham, E., Tisak, D. J., & Williamson, D. F. (2012). Twenty-first century benchmarking: Searching for the next generation. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 19(6), 760–780.

Mi Dahlgaard-Park, S., & Cocks, G. (2012). Creating benchmarks for high performing organisations. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 4(1), 16–26.

Watson, G. H. (1993). Strategic Benchmarking. How to rate your company’s performance against the world’s best. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. Inc.

Watson, G. H. (2007). Strategic benchmarking reloaded with six sigma. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.