13.4. ISO 14001: A Brief Literature Review

In this section, the main research topics of ISO 14001 literature are discussed. The steady rise in adoption of ISO 14001 has attracted the attention of many researchers, who have studied a wide set of topics: the motivations that induce companies to seek this certification (e.g., Bansal & Bogner 2002; Vastag, 2004), the problems encountered during its adoption and management (e.g., Alberti, Caini, Calabrese, & Rossi, 2000; Vastag & Melnyk, 2002), and the effects on firm performance (e.g., De Jong, Paulraj, & Blome, 2014; Paulraj & de Jong, 2011).

Adopting a literature review approach, contributions published in peer-reviewed English-language scientific journals were studied to present the main trends and results about ISO 14001. Reviewed papers were published in a wide set of journals belonging to different disciplines, including operations management, business ethics, economics, innovation, strategic management, and general management. From a geographical point of view, the majority of articles refer to the American continent, followed by Asia and Europe. This distribution partially reflects the global spread of the standard (ISO, 2015). Despite the international dimension of ISO 14001 and the possible influence of country-specific and socioenvironmental factors, only a few papers adopted a cross-country approach (e.g., Johnstone & Labonne, 2008).

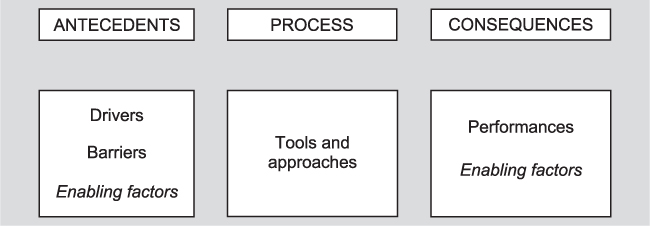

Using the antecedents–process–consequences framework from Narayanan, Zane, and Kemmerer (2011), it is possible to organize the ISO 14001 research topics: the antecedents box consists of drivers/barriers/enabling factors related to the adoption of ISO 14001; the process box summarizes the tools and approaches related to the certification process; and the consequences box focuses on the effects of ISO 14001 on firm performances and their enabling factors (Fig. 13.1).

13.4.1. Antecedents

Many drivers may encourage ISO 14001 adoption. The certification is adopted:

To improve a company’s image. The certification is seen as a tool to gain competitive advantage, improve the company’s external perception (e.g., King, Lenox, & Terlaak, 2005; Viadiu, Fa, & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2006), and exert a positive effect on public opinion (Orsato, 2006).

For ethical reasons. Sometimes companies see the certification as “the right thing to do,” and do not expect an economic return in the short term (Melnyk, Sroufe, & Calantone, 2003b). These ethical reasons seem to prevail at the beginning of the certification process (González-Benito & González-Benito, 2005).

Fig. 13.1: Literature Review Framework.

In response to pressure by customers. The pressure usually comes from larger business clients that play an important role in the supply chain (González, Sarkis, & Adenso-Diaz, 2008). For instance, corporations like Ford, General Motors, and Toyota asked their key suppliers to adopt the certification (Orsato, 2006).

In response to environmental legal requirements. Companies are frequently pushed by regulatory bodies or governments toward the adoption of management practices that ensure a sustainable exploitation of the environment. This is particularly true in some industries (e.g., chemical sector) in which environmental issues are critical (Alberti et al., 2000; Delmas & Montiel, 2009). However, according to Johnstone and Labonne (2008), the use of ISO 14001 certification as a tool for compliance with rules and regulations is useful mainly for larger companies (over 250 employees), which usually are more exposed to inspections.

To benefit from green incentives.

To increase efficiency.

To reduce information asymmetries between suppliers and buyer.

To reduce toxics release.

It is also important to mention that the motivation to adopt ISO 14001 differs during the diffusion period (Baek, 2017). Early adopters mostly use ISO 14001 as a competitive resource, while later adopters are more influenced by institutional pressure. As ISO 14001 spreads, it may be “taken for granted.” Additionally, the importance of motives seems to differ between business sectors and between different countries.

The most important barriers that discourage ISO 14001 adoption are the following:

The risk of spreading confidential information. In many cases, because the certification process is outsourced to consultants (Boiral, 2011), there might be risk of sharing sensitive information (Boiral, 2011). To mitigate this issue, long-term relationships with consultants and legal measures might be adopted (Zutshi & Sohal, 2004a). However, the involvement of unchanging external consultants can create some dependencies (Boiral, 2011).

The reduction in productivity due to administrative tasks required. Certified companies have to archive and manage all the documentation related to environmental impacts and to past actions taken to improve performances (e.g., Bansal & Bogner, 2002). This can lead to a high level of bureaucratization and to the need for dedicated resources (Boiral, 2011). In many cases, companies underestimate the efforts for administrative actions necessary for the ongoing management of the certification (Zutshi & Sohal, 2004b).

Performing a formal (ineffective) implementation of ISO 14001. This is the case of companies that implement the certification mainly for its potential commercial value, rather than for improving business practices. Such a focus limits the efficacy of the ISO 14001.

The cost of certification, defined by some authors as the “cost to be green” (e.g., Orsato, 2006). This cost includes the work of the certification bodies, and the time spent by the company for analyzing their processes, modifying them, developing the necessary documentation, and training the employees (Zutshi & Sohal, 2004b). Besides the initial certification cost, there is also an annual cost for maintaining the certification (e.g., auditing and documentation management) (Bansal & Bogner, 2002). These costs may represent a further obstacle to ISO 14001, especially for small and medium enterprises (e.g., Orsato, 2006).

The difficult outcome evaluation. In particular, the lack of quantifiable benefits is a significant obstacle to actively pursue the certification (Vastag & Melnyk, 2002). Companies driven mainly by economic motivations can see the benefits of ISO 14001 as particularly uncertain (Melnyk, Sroufe, & Calantone, 2003b).

Risk of underestimating the required resources.

Time spent for frequent control visits.

Inadequate technical competence of auditors.

Low employees’ commitment.

Many authors have also studied the variables that may facilitate the adoption of ISO 14001. The role of these variables is to reinforce the drivers’ effect and/or to reduce the barriers’ effect. Among the most important findings, literature shows that

the presence of a previous EMS tends to increase the likelihood to implement the certification. The adoption of a standard/management system could simplify the implementation of another thanks to the experience gained and the possibility to share common activities (King & Lenox, 2001). While most authors agree with this finding, Melnyk et al. (2003b) present a conflicting result. These authors argue that while the new development of an EMS can be seen as an opportunity to become ISO 14001 certified, companies with consolidated EMS are more reluctant to get the certification because they are already internally aligned with environmental requirements.

large companies are more likely to adopt the ISO 14001 certification. The adoption of ISO 14001 requires investments in time and financial resources, and SMEs may have greater difficulties in finding these resources (e.g., Montiel & Husted, 2009). SMEs prefer to use simple formal management tools in order to raise the quality of environmental management, without incurring in high bureaucratic costs. Furthermore, larger companies can obtain the certification more quickly due to higher competences on average. Finally, large firms tend to emphasize more the customers’ requests for the certification, since their corporate marketing division can be more influential (Delmas & Toffel, 2008).

strategic proactivity – defined as the tendency to implement the most advanced and modern practices – encourage companies to adopt ISO 14001. Under this perspective, the adoption of the certification might be seen as a proactive way of managing regulatory changes, community relations, and public opinion (Jiang & Bansal, 2003).

the economic development of headquarters’ region increases the chances to get certified due to a higher availability of skills and resources. However, the certification could be better accepted in emerging economies (e.g., China and Brazil) than in industrialized countries, as the last ones have reached their performance frontier (or are very close to it) and improvements are therefore more difficult to obtain.

the local density of certifications among geographically proximate firms increases the likelihood of obtaining ISO 14001 certification. In particular, the local density of certified companies has a larger effect on domestic firm’s certification decisions and a smaller effect on multinational enterprise subsidiaries.

the ISO 9001 diffusion level in the country affects the adoption of ISO 14001. Because of the similarities between the two standards (also in their implementation paths), positive experiences with ISO 9001 facilitate the adoption of ISO 14001. However, Melnyk et al. (2003b) show that ISO 9001 certified plants are less likely to welcome the ISO 14001 certification. The authors provide two possible explanations for this result: (1) firms having difficulties with ISO 9001 or a bad experience with the certification process are reluctant to start another audit and certification process; and (2) ISO 9001 certified firms often have also an EMS, so they don’t need to be ISO 14001 certified.

13.4.2. Process: The PDCA Cycle and Other Methods

In this section, the literature devoted to tools and methods used with ISO 14001 is presented. The most used method to implement the ISO 14001 is the PDCA cycle. Mentioned by ISO, the approach is focused on a continuous improvement logic and fixed and challenging (environmental) targets. According to the PDCA cycle, the ISO 14001 requires each organization to

develop environmental policies with a commitment to continuous improvement;

identify all the processes and activities that affect environment, and then focus on the most significant for environmental impact;

establish environmental objectives and targets;

develop procedures to control and measure environmental impacts and performances;

train employees on these procedures;

demonstrate an interest to comply with environmental laws and regulation;

conduct internal audits;

periodically review the management systems.

During the Plan stage, the organization should first establish its environmental situation. A clear view of the situation is fundamental to understand the most dangerous processes for the environment, and where the organization need to focus its attention. After a first review of the current situation, the top management has to improve an environmental policy. This step is focused on the definition of a path to follow, specifying which are the organization’s responsibilities about environmental performances. Having established the policy, the top management can define the plan to implement the EMS: the organization has to set out objectives, to plan strategies for their achievement, and to introduce a performance measurement system that takes into account environmental laws and regulations (ISO, 2015b).

During the Do stage, the organization has to develop specific capabilities and create the organizational structure to implement the Plan. It is important to identify the resources required and the members that will be responsible for the EMS’ implementation. The organization has also to define procedures to control all the processes connected to the environment. In this way, all critic processes are under control and negative environmental impacts are avoided. Additionally, it is also necessary to establish emergency procedures to solve or minimize the impacts of potential accidents. It is also important to have strong internal and external communications; the organization needs to develop a system to share documents, registrations, and data about the EMS.

After having implemented the procedures, the performance should be monitored and measured (Check). The organization should control if the Plan established is effective, and if targets and objective are respected. During this stage, internal audits are conducted in order to ensure the respect of targets.

The PDCA cycle ends with a re-examination (Act), conducted by the top management. The top management analyzes the EMS and evaluates if it is effective enough to reach the objectives established during the Plan stage. This final stage is important in order to define new targets and to restart the cycle again.

Other methods used during the ISO 14001 implementation are the following:

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), used for the evaluation of the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s life. LCA is useful to determine direct environmental impacts but also indirect impacts, that are typically harder to be estimated. The technique allows companies to (re)design their products/processes and to improve their practices.

Total Quality Management (e.g., the “team-based” approach, the cross-functional integration, and the enlargement of the employees’ mansions).

A systematic communication with the stakeholders. A bi-directional communication with the external stakeholders can lead to many opportunities, as focusing on the elements that are relevant for them and informing them about the activities already carried out (Paulraj & De Jong, 2011).

Data Envelopment Analysis used in the evaluation of environmental performances. This method can be used to take into consideration different inputs (e.g., trash quantity, CO2 gas emission) and outputs (e.g., total revenues) in order to calculate the global efficiency.

Environmental technologies and monitoring.

Green purchasing.

13.4.3. Consequences on Performance

The impact of ISO 14001 on performance is the most debated topic in the literature, as it happens for other standards (Orzes, Jia, Sartor, & Nassimbeni, 2017; Orzes et al., 2018; Sartor, Orzes, Di Mauro, Ebrahimpour, & Nassimbeni, 2016; Sartor, Orzes, Touboulic, Culot, & Nassimbeni, 2019). It is possible to analyze the performance with the four perspectives of the Kaplan and Norton’s (1992) balanced scorecard: Business Processes, Financial, Customer, Learning, and Growth.

The adoption of ISO 14001 has the following effects on Business Processes:

Increased process productivity and control. During the implementation, employees working in various corporate functions are called to examine and improve their business processes; this usually leads to the achievement of better operational performance (Melnyket al., 2003a). However, Schoenherr and Talluri (2013) show that the certification has a negative effect on productivity: it requires time and often radical changes within the company, that cause a decrease in productivity (at least) in the short term, until the new procedures are assimilated.

Reduced waste and consumption of resources and optimized use of raw materials. Lo, Yeung, and Cheng (2012) focus on the fashion and textiles industries – which sometimes have a high level of emissions – and argue that the adoption of ISO 14001 allows to reduce the pollution production and the associated costs. Darnal and Kim (2012) show that all the types of EMS (i.e., 14001-certified EMSs, complete non-certified EMSs, and incomplete EMSs) lead to a reduction in the use of natural resources, solid wastes, and global air pollutants.

Decreased inspections frequency.

Increased flexibility.

Improved health and safety condition in the workplace.

Considering the Financial Perspective, ISO 14001 certification contributes to

A long-term positive reaction of the financial markets (Jacobs, Singhal, & Subramanian, 2010), since shareholders perceive the certification as a signal of the company’s commitment to align its processes with international best practices, and to improve environmental management as well as operational performance. This positive effect is more significant in those sectors in which the ISO 14001 certification is considered a prerequisite to operate (Jacobs et al., 2010). Additionally, Xu, Zeng, Zou, and Shi (2016) show that firms that are ISO 14001 certified face a smaller decline in stock prices after environmental violation.

More efficient R&D investment and innovation, as the certification improves company-wide practices of resources management and enables firms to better invest their resources.

Improved firms’ profitability and increased sales. Jacobs et al. (2010) claim that ISO 14001 might improve revenues because it enhances the reputation of the certified company.

From a Customer Perspective, ISO 14001 leads to

improved corporate image and reputation. Certified companies are better accepted by external stakeholders (including customers) since they demonstrate more responsibility toward environmental issues (Great & Melnyk, 2002);

increased customer satisfaction; and

increased on time delivery and reduced lead times.

Considering the last perspective, Learning and Growth, ISO 14001 is useful for

better compliance with law/regulations (certified companies are less likely of being cited for violating these regulations);

improved employees’ awareness and morale;

diffusion of environmental practices among supply chain;

improved relations with communities and authorities; and

easier implementation of other environmental practices.

Many studies also analyzed the enabling factors affecting the performance (i.e., factors that contribute to facilitate a good performance). The performance impact of ISO 14001 may be facilitated if companies are characterized by the following:

High strategic coherence (i.e., the consistency between the certification goals, policies, and actions). The interests of shareholders should be aligned to the search of environmental sustainability (Delmas, 2001). Firms should be able to define and effectively communicate: (1) Why the standard should be adopted? (2) Which are the internal advantages? and (3) the nature of the link between these advantages and the mission of the organization.

Top management commitment. An environmentally sensitive top management is able to influence the way in which the certification is adopted, other than its achieved results.

High involvement of employees. Human resources should be aware of the requirements of the standard and should develop training programs on environmental issues (Boiral, 2011). To support and motivate employees, incentive mechanisms are welcome.

Big company size. Paulraj and De Jong (2011) show that the negative reaction of the financial market that follows the announcement of the certification is less significant for large companies. This is mainly because large companies may more easily reassure investors that the decision to pursue the certification is the result of a careful analysis about costs and benefits, persuading them that the certification is the right strategic decision (Paulraj & De Jong, 2011). Schoenherr (2012) echoes that the effect of ISO 14001 on operational performance is higher for large companies.

Stakeholders’ involvement (suppliers, customers, government agencies, and shareholders). It can contribute to make the adoption of ISO 14001 more effective. Among the ISO 14001 certified firms, having green suppliers increase environmental performances and competitive advantage.

Belonging to a chemical sector. Companies that operate in the chemical sector tend to achieve the best results after the ISO 14001 adoption. On the contrary, companies competing in the machinery, electronic, and electrical components industries obtain the worst results. This can be explained by the fact that the short-term certification impact is less significant in these sectors, since improvements in the processes require a long-term redesign (Schoenherr, 2012). Furthermore, Chiarini (2014) argues that manufacturing companies are not as confident as service companies that ISO 14001 would be an effective strategy for improving the environmental performance of the supply chain.

Early implementation timing relative to industry rivals. The performance benefits increase if companies anticipate their rivals in the adoption of ISO 14001, because they can first demonstrate their environmental sensitivity and then gain a competitive advantage.

EMS designed around existing internal processes. In this way, the EMS can be more effective because it is not necessary to revolutionize the processes.

Duration of ISO 14001.

Plants located in countries with strong and flexible environmental regulation. A flexible regulation allows companies to invent and create innovative solutions, which are the key for reducing costs and obtaining an excellent performance.

Strong internal motivation.