16

SA 8000

Marco Sartor and Guido Orzes

16.1. Introduction

The acronym SA 8000 identifies an international certification standard aiming to ensure specific aspects of business management related to corporate social responsibility (CSR).

The standard was codified in New York in 1997, in conjunction with the establishment of the Council on Economic Priorities Accreditation Agency, later renamed as Social Accountability International. It was created to tackle exploitation, discrimination, and lack of recognition of workers’ rights, seeking to ensure fair and safe working conditions.

The standard was updated twice. Four years after its encoding (in 2001), it was partially amended to take into account aspects neglected in the first draft (aspects related to discrimination, overtime and subcontractors control in particular). In 2008, it underwent further revision: SA 8000:2008 was published, which, however, showed limited changes compared to the previous edition.

According to SA 8000, the organization that seeks certification – besides respecting national, international, and industry regulations – shall consider the requirements defined in the standard. Where different regulations apply at the same time, the company must follow the strictest one.

A distinctive element of SA 8000 lies in its promoting proactive attitudes: those seeking certification should not simply attain to verifying compliance with the standards, but must define plans aimed at anticipating and thus discouraging those situations, which may be detrimental for workers’ rights. Another feature concerns the application of the requirements not only to the company seeking certification, but also to the entire supplier network: thus it becomes essential to develop an adequate control system addressed and welcomed by the whole supply system (Ciliberti, Pontrandolfo, & Scozzi, 2008).

The principles the standard is based on are drawn from International Labour Organization (ILO) Conventions and Recommendations, the International Declaration of Human Rights, the UN International Convention on the Rights of the Child and the UN Convention to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women (Lafratta, 2004).

SA 8000 certification immediately brings tangible benefits to companies adopting it. A safe working environment, where care is given to education and staff needs, seems to improve business climate, favoring employees’ loyalty and increasing productivity. The improved company image also seems to increase customer satisfaction. Adherence to strong moral principles ensures better relationships with all stakeholders. Finally, there are indirect benefits ranging from reduced non-quality costs to lower labor issues (Lepore & D’Alesio, 2004).

The certified companies in the world are over 2,000, in more than 60 countries.

16.2. Structure of the Standard

SA 8000 comprises four sections: the first three sections introduce the purpose of the standard, national, and international references and definitions. The fourth section, divided into nine points, illustrates social responsibility requirements and describes the management system to implement. The first eight requirements relate to child labor, forced labor, health and safety at work, freedom of association and right to collective bargaining, discrimination, disciplinary practices, working hours, and remuneration. The ninth requirement codifies the application of the standard and regulates the management procedures of the company seeking certification.

16.2.1. Requirement 1: Child Labor

Child labor is any work by a child.

The standard defines the term “child” any person less than 15 years of age, unless the minimum age for work is stipulated as being higher by local law, in which case the stipulated higher age applies. However, if the minimum set age is lower, it is applicable only if in accordance with the exceptions for developing countries adhering to ILO Convention 138.

For “young worker,” instead, the standard means any worker over the age of a child and under the age of 18.

SA 8000 calls for the company not to resort to child labor. The right to schooling for young workers is established, with a maximum limit of 10 hours to include study, employment, and transportation, ensuring that in no case working time will concur with school or night time. Finally, it is forbidden to expose children to situations that are hazardous, unsafe, or unhealthy. ILO Convention 138, Article 3, par. 1 raises the age limit to 18 years for all those work situations that can compromise health, safety, and morals of a young worker. Compliance to the standard is assessed through the analysis of personal identity documents. Where minors are present, it is necessary to check that working hours and work type conform to requirements, through check-ins and checkouts at the attended school (Lepore & D’Alesio, 2004).

16.2.2. Requirement 2: Forced Labor

Forced labor refers to all cases where the choice to work is not carried out freely by the individual, but is forced by an explicit or implicit threat of punishment. This is not unpaid or inadequately paid work, but it is compulsory since the freedom of the worker is limited and therefore, he is unable to choose a service freely. The most widespread forms of forced labor occur as a result of debt with the employer: the employee is thus no longer able to escape and is bound to the company. SA 8000 condemns all forms of forced labor, banning such abuse. In fact,

personnel shall have the right to leave the workplace premises after completing the standard workday, and be free to terminate their employment provided that they give reasonable notice to their employer. (Requirement 2.3 of SA 000:2008)

ILO Convention 29 lists the exceptional cases where forced labor is allowed, such as civic or military duties or force majeure cases.

The company aiming at the ethical certification must ensure that workers do not fall into debt with the company itself, and must provide evidence, through contracts signed by workers, that the work or service is voluntary. It must also avoid the presence at work of guards or military personnel who could intimidate employees: alternatively, their role must be proven in relation to security measures. Finally, the law stipulates that the company must not withhold personnel’s original identity documents, cash, or other deposits, which may constrain them (Lepore & D’Alesio, 2004).

16.2.3. Requirement 3: Health and Safety

With this requirement, the standard establishes the importance for a company to “provide a safe and healthy workplace environment” and take effective steps to prevent potential accidents. The company, in fact, should not simply assess the safety of the workplace, but must implement proactive measures to identify possible causes of hazard and deal with risks before incidents occur. Once the policy is established, the company shall spread it, train all personnel, and appoint a senior management representative to be responsible for ensuring a safe and healthy workplace environment. The last paragraphs sanction the importance of a healthy work environment, with toilet provision meeting standards requirements, with readily available and free drinking water and, where called for, clean facilities suitable for the storage of food, away from sources of pollution, or contamination. Finally, where dormitories are provided for, they should be “clean, safe” and should meet “the basic needs of the personnel” (Requirement 3.8-SA 8000:2008).

Companies wishing to be certified must supply a document outlining their health and safety policy, including coded procedures to prevent accidents, as well as documentation issued by the competent authority certifying that the site is suitable. There must also be evidence of documentation related to personnel training on the subject, and to the existence of a security officer. The structure must provide firefighting and first aid equipment as well as personnel trained to their use, emergency exits, and free and accessible escape routes. The company shall maintain written records of all accidents that occur, define an evacuation plan and produce documents related to the carried out exercises (Lepore & D’Alesio, 2004).

16.2.4. Requirement 4: Freedom of Association and Right to Collective Bargaining

A company must grant all members of staff the opportunity to join freely the trade unions of their choosing, and the right to collective bargaining, that is, the relationship between workers’ trade unions and employers groups, from which the agreements to be followed by the individual employment contracts will derive. Thus, not only the freedom of association and collective bargaining is sanctioned, but also where this is not provided for, the company shall facilitate parallel means of independent and free association. According to SA 8000, trade unions are allowed to communicate with their members in the workplace.

The certifying body shall verify the existence of trade union representatives, ensuring that they are not subjected to discrimination, as well as the attitude of the company to recognize the unions as part of collective bargaining. It must also verify the existence of an SA 8000 workers’ representative and that the employer is willing to offer adequate space for union meetings.

16.2.5. Requirement 5: Discrimination

In a company committed to ethics, there must be “equality of opportunity or treatment in employment or occupation” (Art 1-ILO Convention 111): the standard condemns any act of discrimination in terms of “hiring, remuneration, access to training, promotion, termination or retirement” or any attempt to “interfere with the exercise of the rights of personnel to observe tenets or practices” he believes in (Requirements 5.1, 5.2-SA 8000: 2008). Women and disabled people are among the most discriminated categories, even in developed and industrialized contexts, as they receive limiting treatment in terms of professional development, hiring, and training. Finally, the standard condemns any “behaviour that is threatening, abusive or exploitative” (Requirement 5.3-SA 8000:2008) and which may cause attitudes of rejection and self-exclusion in the victim.

The certification body must examine payrolls, ensuring that there are no differences in wages for equal work performances, and analyze hiring methods, change of duties, or dismissal reasons for the past three years. In case of workers belonging to different religions or cultures, the company shall provide evidence that the menu (if available) takes into account the different traditions and habits, and that workers are allowed to observe holidays and religious practices. Finally, it must establish a policy for career advancement, provide workers indications on how to anonymously file a complaint against the company, and allow them to appoint a representative who can report to management any case of discrimination (Lepore & D’Alesio, 2004).

16.2.6. Requirement 6: Disciplinary Procedures

The law refers to all cases where an employer, when condemning workers wrong behaviors, violates their rights. The company shall not engage in or tolerate the use of corporal punishment, mental or physical coercion, or verbal abuse of personnel, which can cause psychological pressure on them. In industrialized countries, in fact, disciplinary procedures are already codified, such as verbal warnings, written warnings, sanctions, suspension from work, and withholding of salary payment. To aggravate things, aggressive employer behavior is often not connected to wrong employees’ conduct: it is purely aimed at intimidating them and thus generate a state of absolute obedience within the company.

To obtain certification, a company must have a disciplinary code, with sanctions complying with current standards, and the whole staff must be aware of it; anomalies in payrolls may highlight uncoded punitive treatment. Finally, there must be instruments to enable employees to report disciplinary procedures which are not in compliance with standards (Lepore & D’Alesio, 2004).

16.2.7. Requirement 7: Working Hours

SA 8000 states that, when defining working hours, the company should comply with the specific standards and area contracts issued for the sector it belongs to. In any case, it defines a threshold for the number of weekly working hours (48) and calls for at least one day off every six working days; if sectoral agreements entailed more disadvantageous conditions, the company seeking certification should refer to the more restrictive parameters provided for by the standard. It should be noted that the standard does not refer to holidays or periods of rest during the working year, since they are provided for only in some contexts.

The overtime issue is also addressed, that is, all work performed outside the ordinary working hours. Under no circumstances, it shall exceed 12 hours per employee per week and shall be reimbursed at a premium rate. According to the standard, overtime shall be exceptional and voluntary, except for market emergencies, always mediated through collective bargaining.

To earn certification, the company must show objective evidence relating to respect for national (or sector) collective bargaining and compliance with the standard. It must demonstrate the need for overtime and premium rate compared to ordinary work, highlighting the difference in the payroll. The certification body has the right to check (through the analysis of the percentage of accidents or of production levels) any unregistered overtime (Lepore & D’Alesio, 2004).

16.2.8. Requirement 8: Remuneration

The company must meet legal or industry minimum standards for salaries too (e.g., sectoral agreements); remuneration, however, must allow the employees to meet their basic needs and provide some discretionary income. The company shall not resort to salary reduction for disciplinary purposes, use labor-only contracting arrangements and/or false apprenticeship schemes to avoid fulfilling its obligations to personnel under applicable laws pertaining to labor and social security legislation and regulations.

16.2.9. Requirement 9: Management System

The ninth requirement encodes management procedures related to the application of the standard to the company and the supply chain. It is divided into subsections.

16.2.9.1. Policy

9.1. Top management shall define in writing, in workers’ own language, the company’s policy for social accountability and labor conditions, and display this policy and the SA 8000 standard in a prominent, easily viewable place on the company’s premises, to inform personnel that it has voluntarily chosen to comply with the requirements of the SA 8000 standard. Such policy shall clearly include the following commitments:

(a) to conform to all requirements of this standard;

(b) to comply with national and other applicable laws and other requirements to which the company subscribes and to respect the international instruments and their interpretation (as listed in Section II above);

(c) to review its policy regularly in order to continually improve, taking into consideration changes in legislation, in its own code-of-conduct requirements, and any other company requirements;

(d) to see that its policy is effectively documented, implemented, maintained, communicated, and made accessible in a comprehensible form to all personnel, including directors, executives, management, supervisors, and staff, whether directly employed by, contracted with, or otherwise representing the company; and

(e) to make its policy publicly available in an effective form and manner to interested parties, upon request.

16.2.9.2. Management Representative

9.2. The company shall appoint a senior management representative who, irrespective of other responsibilities, shall ensure that the requirements of this standard are met.

16.2.9.3. Employees’ SA 8000 Representative

9.3. The company shall recognize that workplace dialogue is a key component of social accountability and ensure that all workers have the right to representation to facilitate communication with senior management in matters relating to SA 8000. In unionized facilities, such representation shall be undertaken by recognized trade union(s). Elsewhere, workers may elect a SA 8000 worker representative from among themselves for this purpose. In no circumstances, shall the SA 8000 worker representative be seen as a substitute for trade union representation.

16.2.9.4. Management Review

9.4. Top management shall periodically review the adequacy, suitability, and continuing effectiveness of the company’s policy, procedures, and performance results vis-à-vis the requirements of this standard and other requirements to which the company subscribes. Where appropriate, system amendments and improvements shall be implemented. The worker representative shall participate in this review.

16.2.9.5. Planning and Implementation

9.5. The company shall ensure that the requirements of this standard are understood and implemented at all levels of the organization. Methods shall include, but are not limited to:

(a) clear definition of all parties’ roles, responsibilities, and authority;

(b) training of new, reassigned, and/or temporary personnel upon hiring;

(c) periodic instruction, training, and awareness programs for existing personnel; and

(d) continuous monitoring of activities and results to demonstrate the effectiveness of systems implemented to meet the company’s policy and the requirements of this standard.

9.6. The company is required to consult the SA 8000 Guidance Document for interpretative guidance with respect to this standard.

16.2.9.6. Control of Suppliers/Subcontractors and Subsuppliers

9.7. The company shall maintain appropriate records of suppliers/subcontractors’ (and, where appropriate, subsuppliers’) commitments to social accountability, including, but not limited to, contractual agreements and/or the written commitment of those organizations to:

(a) conform to all requirements of this standard and to require the same of subsuppliers;

(b) participate in monitoring activities as requested by the company;

(c) identify the root cause and promptly implement corrective and preventive action to resolve any identified nonconformance to the requirements of this standard; and

(d) promptly and completely inform the company of any and all relevant business relationship(s) with other suppliers/subcontractors and subsuppliers.

9.8. The company shall establish, maintain, and document in writing appropriate procedures to evaluate and select suppliers/subcontractors (and, where appropriate, subsuppliers) taking into account their performance and commitment to meet the requirements of this standard.

9.9. The company shall make a reasonable effort to ensure that the requirements of this standard are being met by suppliers and subcontractors within their sphere of control and influence.

9.10. In addition to the requirements of Sections 9.7–9.9 above, where the company receives, handles, or promotes goods and/or services from suppliers/subcontractors or subsuppliers who are classified as home workers, the company shall take special steps to ensure that such home workers are afforded a level of protection similar to that afforded to directly employed personnel under the requirements of this standard. Such special steps shall include, but not be limited to:

(a) establishing legally binding, written purchasing contracts requiring conformance to minimum criteria in accordance with the requirements of this standard;

(b) ensuring that the requirements of the written purchasing contract are understood and implemented by home workers and all other parties involved in the purchasing contract;

(c) maintaining, on the company premises, comprehensive records detailing the identities of home workers, the quantities of goods produced, services provided, and/or hours worked by each home worker; and

(d) frequent announced and unannounced monitoring activities to verify compliance with the terms of the written purchasing contract.

16.2.9.7. Addressing Concerns and Taking Corrective Action

9.11. The company shall provide a confidential means for all personnel to report nonconformances with this standard to the company management, and the worker representative. The company shall investigate, address, and respond to the concerns of personnel and other interested parties with regard to conformance/nonconformance with the company’s policies and/or the requirements of this standard. The company shall refrain from disciplining, dismissing, or otherwise discriminating against any personnel for providing information concerning observance of the standard.

9.12. The company shall identify the root cause, promptly implement corrective and preventive action, and allocate adequate resources appropriate to the nature and severity of any identified nonconformance with the company’s policy and/or the standard.

16.2.9.8. Outside Communication and Stakeholder Engagement

9.13. The company shall establish and maintain procedures to communicate regularly to all interested parties data and other information regarding compliance with the requirements of this document, including, but not limited to, the results of management reviews and monitoring activities.

9.14. The company shall demonstrate its willingness to participate in dialogues with all interested stakeholders, including, but not limited to: workers, trade unions, suppliers, subcontractors, subsuppliers, buyers, non-governmental organizations, and local and national government officials, aimed at attaining sustainable compliance with this standard.

16.2.9.9. Access for Verification

9.15. In the case of announced and unannounced audits of the company for the purpose of certifying its compliance with the requirements of this standard, the company shall ensure access to its premises and to reasonable information required by the auditor.

16.2.9.10. Records

9.16. The company shall maintain appropriate records to demonstrate conformance to the requirements of this standard.

16.3. SA 8000: Advantages and Obstacles

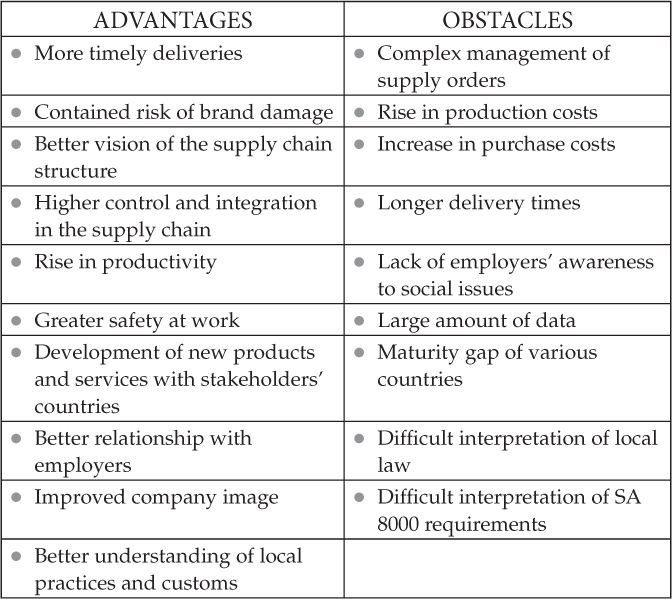

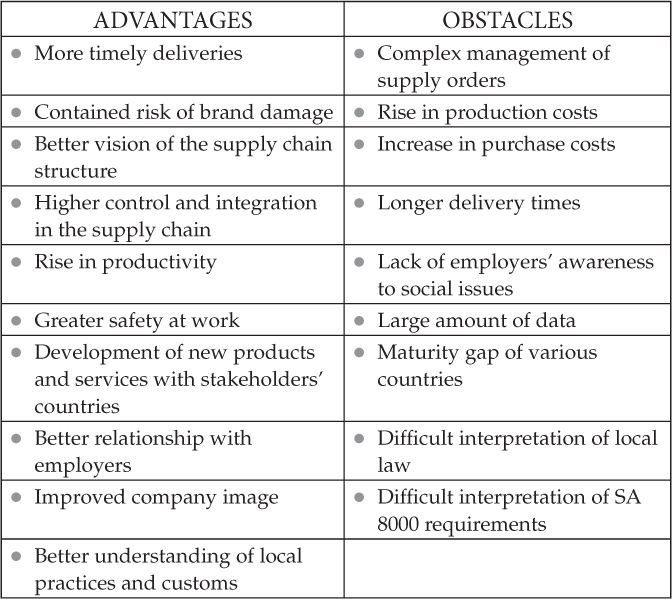

From the comparative analysis of the experiences of different SA 8000 certified companies (e.g., GAP, Gucci, Tata Steel, and TNT), it was possible to identify the main benefits and the major problems of the certification (Fig. 16.1).

The main advantages are:

More timely deliveries. SA 8000 requires a certified company to carry out conformity inspections on the supply system. This leads to more timely and rigorous deliveries.

Contained risk of brand damage. The control of the supply chain –essential requirement to achieve certification – ensures accurate and consistent conformity to the standard of all the activities belonging to the supply chain. These checks guarantee the certified company that the risk of being exposed to scandals – due to inappropriate actions by suppliers or subsuppliers – is significantly reduced.

Fig. 16.1: SA 8000 – Advantages and Obstacles.

Better vision, control, and integration in the supply chain. Audits and conformity inspections undertaken by the certified organization provide a clear view of the supply chain structure. This is the starting point for greater collaboration between the various stakeholders.

Increased productivity. The attention paid by the standard to training courses for personnel leads to an increase in production efficiency, both for management and workers. For example, after certification Tata Steel has measured a tangible productivity increase in operations such as mechanical and electrical assembly, gas cutting, and welding. The same improvement was also observed by its suppliers.

Greater safety at work. The standard establishes the importance of ensuring a healthy and safe work place. To comply with this requirement, Tata Steel, as an example has carried out an analysis of data on the accidents occurred and has taken advantage of advice and effective direct communication to personnel to disseminate safety rules and precautions.

Development of new products and services in collaboration with stakeholders. The stakeholders’ appreciation of ethical issues can lead to a collaboration between stakeholders in the development process of new products or services. TNT, for example, through this collaboration reached a joint development of new services.

Better relationship with employees. Within a certified company, not only all workers are entitled to their rights, but also communication with top management is facilitated. TNT certification generated greater employees’ confidence in the company.

Improved company image. Following certification, the company brand becomes expression of ethical principles and social responsibility.

Better understanding of local practices and customs. The adoption of the standard by companies operating in different cultural contexts allows these companies to understand local practices and traditions and engage with them.

However, the certification process is not free from difficulties; the main obstacles are

Complex management of supply orders. Work-related policies called for by the standard (in terms of rest periods, use of overtime, etc.) represent a constraint to the flexibility of the certified company and its suppliers. This forces the company to carefully plan supply orders; errors are likely to be difficult to correct.

Increase in production and buying costs. The process toward SA 8000 requires the company to carry out expenditures to implement the ethical management system (e.g., for advice and monitoring). After implementation, there are inevitable increases in production and procurement costs due to the application of the standards and the required controls. Some Otto Group suppliers, for example, further to certification have observed higher costs (about 12% in India and Pakistan) to legalize employees’ positions and to manage the required controls; these costs have resulted in an increase in Otto Group supplies costs.

Longer delivery times. In some cases, the checks required by the standard have resulted in an increase in the average delivery time.

Lack of employees’ awareness of social issues. Ironically, in underdeveloped contexts, workers prove occasionally more drawn to companies that make use of “unregulated” overtime or to those offering jobs which are irregular and hazardous for the health, rather than SA 8000 certified companies. Although these ensure more decent working conditions, potential profits are at times lower.

Large amount of data. The continuous monitoring required by the certification can generate an excessive amount of data, if efficient tools are not available. For example, in its first approach to SA 8000 implementation, Tata Steel produced substantial documentation on audits. Later on, paper-based data were replaced by the “Tata Steel SA 8000 Vendor Assessment Protocol,” which automatically generates evaluations for each of the nine requirements of the standard.

Difficult interpretation of local laws and SA 8000 requirements. Often, the interpretation of laws in those countries where a company operates or the same SA 8000 requirements lend themselves to misunderstandings. TNT, for example, has experienced delays in the certification process due to misunderstandings on the standards as well as on local laws and regulations.

16.4. SA 8000, ISO 9001, and ISO 14001

Several studies in literature jointly analyze SA 8000 with ISO 9001 and ISO 14001.

The most relevant research field is devoted to the analysis of the joint adoption of these certifications and to the benefits related to the development of an integrated management system (e.g., Jørgensen, Remmen, & Mellado, 2006; Karapetrovic & Casadesús, 2009; Kortelainen, 2008; Salomone, 2008).

The literature shows that having been certified under ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 helps in the implementation of SA 8000. For instance, several ISO 9001 principles, such as the involvement of people at all levels, the process approach (i.e., the horizontal management able to cross the barriers between different functions and unifying their focus), and the system approach (i.e., the identification, understanding, and management of interrelated processes as a system), contribute to the organization’s effectiveness and efficiency, but also accelerates the achievement of SA 8000, as it is based on similar principles (Kortelainen, 2008; Ruževičius & Serafinas, 2007).

With regard to the matching of ISO 9001, ISO 14001, and SA 8000 in an integrated management system, empirical (e.g., Salomone, 2008; Tsai & Chou, 2009) and conceptual literature (e.g. Jørgensen et al., 2006) are in agreement that the integration leads to significant benefits, such as the reduction in the cost of ongoing management of all of the single certifications. With reference to the path followed by the companies toward an integrated management system, it usually goes through the adoption of the ISO 9001, then the ISO 14001 (and OSHAS 18000) and, finally, the SA 8000. The average leadtime for the implementation of the first certification is 19 months, the second standard takes an average of 15 months, and the averages for the third is 11 months.

16.5. SA 8000 and Other CSR Standards/Codes of Conduct

The increasing need for protection and improvement of working conditions has led to the development of several ethical standards and codes of conduct. Some studies focus on the comparison between SA 8000 and these standards, including Global Compact (GC), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), AccountAbility 1000 (AA 1000), ISO 26000, FLA Workplace Code, and China Social Compliance 9000 for Textile & Apparel Industry (CSC9000T) (Orzes et al., 2018; Orzes, Jia, Sartor, & Nassimbeni, 2017; Sartor, Orzes, Di Mauro, Ebrahimpour, & Nassimbeni, 2016; Sartor, Orzes, Touboulic, Culot, & Nassimbeni, 2019).

A group of studies (e.g., Behnam & MacLean, 2011; Rasche, 2009, 2010) present the SA 8000 strengths compared to the other CSR standards. SA 8000 is better able to address human and labor rights explicitly throughout the company, raise public awareness about the company’s efforts, and allow longitudinal comparisons composed of a limited set of dimensions. Partially conflicting results concern the effectiveness of SA 8000 when compared to the other social standards. On the one side, as a certification standard, SA 8000 should have a higher effectiveness. For instance, GC, unlike SA 8000, neither provides quantitative benchmarks nor requires performance measurements. ISO 26000, unlike SA 8000, does not have explicit requirements and is not certifiable. According to some authors (e.g., Gilbert, Rasche, & Waddock, 2011; Rasche, 2009, 2010), this should make SA 8000 more effective.

On the other side, SA 8000 (in addition to AA1000, GC, GRI, and ISO 26000), which is neither industry nor country-specific (on the contrary, the FLA Workplace Code is focused on the textile, apparel, and footwear industries and is adopted mainly by North American firms; CSC9000T is specific to Chinese textile and apparel companies), should be less effective.

The literature also highlights some similarities between these social standards. They all represent a significant tool in customers’ ability to differentiate some products (e.g., textile and clothing goods), especially among more sophisticated Western consumers, who demand more environmentally and socially friendly products (e.g., Battaglia, Testa, Bianchi, Iraldo, & Frey, 2014). They are positively correlated in some industries with two facets of competitiveness: innovation (both from the technical and organizational point of view) and intangible performance (e.g., motivation; Battaglia et al., 2014).

References

Battaglia, M., Testa, F., Bianchi, L., Iraldo, F., & Frey, M. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and competitiveness within SMEs of the fashion industry. Evidence from Italy and France. Sustainability, 6(2), 872–893.

Behnam, M., & MacLean, T. L. (2011). Where is the accountability in international accountability standards? A decoupling perspective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(1), 45–72.

Ciliberti, F., Pontrandolfo, P., & Scozzi, B. (2008) Logistics social responsibility: Standard adoption and practices in Italian companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 113(1), 88–106.

Gilbert, D.U., Rasche, A., & Waddock, S. (2011). Accountability in a global economy: The emergence of international accountability standards. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(1), 23–44.

Jørgensen, T. H., Remmen, A., & Mellado, M. D. (2006). Integrated management systems – Three different levels of integration. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(8), 713–722.

Karapetrovic, S. & Casadesús, M., (2009). Implementing environmental with other standardized management systems: Scope, sequence, time and integration. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(5), 533–540.

Kortelainen, K. (2008). Global supply chains and social requirements: Case studies of labour condition auditing in the People’s Republic of China. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(7), 431–443.

Lafratta, P. (2004). Strumenti innovativi per lo sviluppo sostenibile. Vision 2000, ISO 14000, EMAS, SA 8000, OHSAS, LCA: l’integrazione vincente. Milan, Italy: Franco Angeli.

Lepore, G., & D’Alesio, M. V. (2004). La certificazione etica d’impresa. La norma SA 8000 ed il quadro legislativo. Milan, Italy: Franco Angeli.

Orzes, G., Jia, F., Sartor, M., & Nassimbeni, G. (2017). Performance implications of SA8000 certification. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 37(11), 1625–1653.

Orzes, G., Moretto, A. M., Ebrahimpour, M., Sartor, M., Moro, M., & Rossi, M. (2018). United nations global compact: Literature review and theory-based research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 177, 633–654.

Rasche, A. (2009). Toward a model to compare and analyze accountability standards – The case of the un global compact. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(4), 192–205.

Rasche, A. (2010). The limits of corporate responsibility standards. Business Ethics: A European Review, 19(3), 280–291.

Ruževičius, J., & Serafinas, D. (2007). The development of socially responsible business in Lithuania. Engineering Economics, 1(51), 36–43.

Salomone, R. (2008). Integrated management systems: Experiences in Italian organizations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(16), 1786–1806.

Sartor, M., Orzes, G., Di Mauro, C., Ebrahimpour, M., & Nassimbeni, G. (2016). The SA8000 social certification standard: Literature review and theory-based research agenda. International Journal of Production Economics, 175, 164–181.

Sartor, M., Orzes G., Touboulic, A., Culot, G., & Nassimbeni, G. (2019). ISO 14001 standard: Literature review and theory-based research agenda. Quality Management Journal, 26(1), 32–64.

Tsai, W.-H., & Chou, W.-C. (2009). Selecting management systems for sustainable development in SMEs: a novel hybrid model based on DEMATEL, ANP, and ZOGP. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(2), 1444–1458.