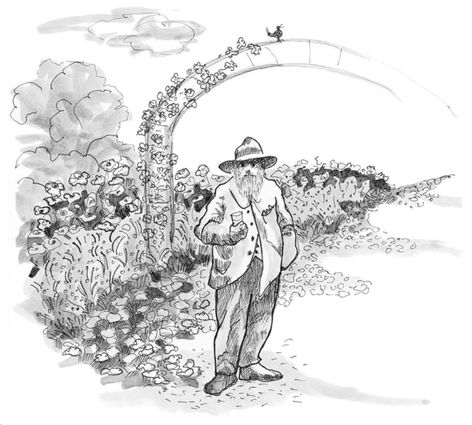

What would the garden be without the paintings? Would I be standing in it (the garden, Claude Monet’s garden), looking at the leaf-green arches on which were trained roses (‘American Pillar,’ ‘Dainty Bess,’ ‘Paul’s Scarlet Rambler’) and clematis (‘Montana Rubens’), looking at the beds of opium poppies, Oriental poppies, looking at the sweep of bearded iris (they had just passed bloom), looking at dottings of fat peonies (plants only, they had just passed bloom), and looking at roses again, this time standardized, in bloom in that way of the paintings (the real made to shimmer as if it will vanish from itself, the real made to seem so nearby and at the same time so far away)?

It was June. I was standing looking at the solanum ‘Optical Illusion’ (Monet himself grew the species Solanum retonii but

solanum ‘Optical Illusion’ is what I saw on a label placed next to this plant) and the hollyhock ‘Zebrina’ (they were in bloom in all their simple straightforwardness, their uncomplicated mauve-colored petals streaked with lines of purple, and this color purple seemed innocent of doubt); looking at the other kind of hollyhock, rosea, which was only in bud, so I could not surreptitiously filch the seedpods; looking at the yellow-flowering thalictrum, the poppies again (only this time they were field poppies, Papaver rhoeas, and they were in a small area to the side of the arches of roses, but you can’t count on them being there from year to year, for all the poppies sow themselves wherever they want); looking at an area of lawn set off by apple trees trained severely along a fence made of wire painted green and beech posts.

I was looking at all these things, but I had their counterparts in Monet’s paintings in my mind. It was June, so I had missed the lawn full of blooming daffodils and fritillarias, they came in the spring. And all this was only the main part of the garden, separate from the water garden, famous for the water lilies, the wisteria growing over the Japanese bridge, the Hoschedé girls in a boat.

And would the water garden be the same without the paintings? On the day (days) I saw it, the water garden—that is, the pond with lilies growing in it—the Hoschedé girls were not standing in a boat on the pond, for they have been dead for a very long time now, and if I expected them to appear standing in the boat, it is only because the pond itself looked so familiar, like the paintings, shimmering (that is sight), enigmatic (that is feeling, or what you say about feeling when you mean many things), and new (which is what you say about something you have no words for yet, good or bad, accept or reject: “It’s new!”)—yes, yes, so familiar from the paintings.

But when I saw the water garden itself (the real thing, the thing that Monet himself had first made and the thing that has become only a memory of what he had made after he was no longer there to care about it, he had been dead a long time by then), it had been restored and looked without doubt like the thing Monet had made, a small body of water manipulated by him, its direction coming from a natural source, a nearby stream. On the day I saw it, the pond, the Hoschedé girls (all three of them) were not in a boat looking so real that when they were seen in that particular painting (The Boat at Giverny) they would then define reality. The Hoschedé girls were not there, for they had long been dead also, and in fact, there were no girls in a boat on the pond, only a woman, and she was in a boat and holding a long-handled sieve, skimming debris from the surface of the pond. The pond itself (and this still is on the day that I saw it) was in some flux, water was coming in or water was going out, I could not really tell (and I did not really want to know). The water lilies were lying on their sides, their roots exposed to clear air, but on seeing them that way I immediately put them back in the arrangement I am most familiar with them in the paintings, sitting in the water that is the canvas with all their beginnings and all their ends hidden from me. The wisteria growing over the Japanese bridge was so familiar to me (again), and how very unprepared I was to see that its trunk had rotted out and was hollow and looked ravaged, and ravaged is not what Monet evokes in anyone looking at anything associated with him (even in the painting he made of Camille, his wife before Alice, dead, she does not look ravaged, only dead, as if to be dead is only another way to exist). But to see these things—the wisteria, the Japanese bridge, the water lilies, the pond itself (especially the pond, for here the pond looks like a canvas)—is

to be suddenly in a whirl of feelings. For here is the real thing, the real material thing: wisteria, water lily, pond, Japanese bridge—in its proper setting, a made-up landscape in Giverny, made up by the gardener Claude Monet. And yet I see these scenes now because I had seen them the day before in a museum (the Musée d’Orsay) and the day before that in another museum (the Musée Marmottan) and many days and many nights (while lying in bed) before that, in books, and it is the impression of them (wisteria, water lily, pond, Japanese bridge) that I had seen in these other ways before (the paintings in the museums, the reproductions in the books) that gave them a life, a meaning outside the ordinary.

A garden will die with its owner, a garden will die with the death of the person who made it. I had this realization one day while walking around in the great (and even worthwhile) effort that is Sissinghurst, the garden made by Vita Sackville-West and her husband, Harold Nicolson. Sissinghurst is extraordinary: it has all the impersonal beauty of a park (small), yet each part of it has the intimacy of a garden—a garden you could imagine creating yourself if only you were so capable. And then again to see how a garden will die with the gardener, you have only to look at Monet’s friend and patron Gustave Caillebotte; the garden he made at Petit Gennevilliers no longer exists; the garden in Yerres, where he grew up, the one depicted in some of his paintings, is mostly in disarray. When I saw the potagerie, the scene that is the painting Yerres, in the Kitchen Garden: Gardeners Watering the Plants was now a dilapidated forest of weeds: a cat who looked as if it belonged to no one stared crossly at me; a large tin drum stood just where you might expect to see a gardener, barefoot and carrying two watering cans. The Yerres River itself no longer seemed wide and deep and mysteriously shimmering (as in Boater Pulling In his Périssoire, Banks of the Yerres or Bathers, Banks of the Yerres), it was now only ordinarily meandering, dirty, like any old memory.

And so, would the garden, in Giverny, in which I was standing one day in early June, mean so much to me and all the other people traipsing around without the paintings? The painting The Artist’s

Garden at Giverny is in a museum in Connecticut, the painting The Flowering Arches is in a museum in Arizona, the painting The Japanese Footbridge is in a museum in Houston, Water Lilies are everywhere. On seeing them, these paintings, either in the setting of a museum or reproduced in a book, this gardener can’t help but long to see the place they came from, the place that held the roses growing up arches, the pond in which the lilies grew, the great big path (called the Grand Allée) that led from the front door of the house and divided the garden in two, the weeping willow, the Japanese bridge, the gladiolas (they were not yet in bloom when I was there), the peonies (they were past bloom when I was there), the dahlias (they were not yet in bloom when I was there).

That very same garden that he (Monet) made does not exist; that garden died, too, the way gardens do when their creators and sustainers disappear. And yet the garden at Giverny that he (Monet) made is alive in the paintings, and the person seeing the paintings (and that would be anyone, really) can’t help but wonder where they came from, what the things in the painting were really like in their vegetable and animal (physical) form. In the narrative that we are in (the Western one), the word comes before the picture; the word makes us long for a picture, the word is never enough for the thing just seen—the picture!

The garden that Monet made has been restored to itself, has been restored so that when we now look at it, there is no discrepancy, it is just the way we remember it (but this must be the paintings), it is just the way it should be. As I was standing there in June (nearby were tray upon tray of ageratum seedlings about to be planted out in a bedding), a man holding a camera (and he was the very definition of confidence) said to me, “Monet knew exactly what he was doing.” I did

not say to him that people who know exactly what they are doing always end up with exactly what they are doing.

The house at Giverny in which he (Monet) lived has also been restored. It can be seen, a tour of the house and garden is available. As I was going through the rooms of the house—the yellow dining room, the blue kitchen, the bedrooms with the beds all properly made up, the drawing room with prints of scenes and people from Japan—I hurried, I rushed through. I felt as if at any moment now, the occupant, the owner (Monet, whoever it might be) would return and I would be caught looking into someone’s private life. I would be caught in a place I was not really meant to be.