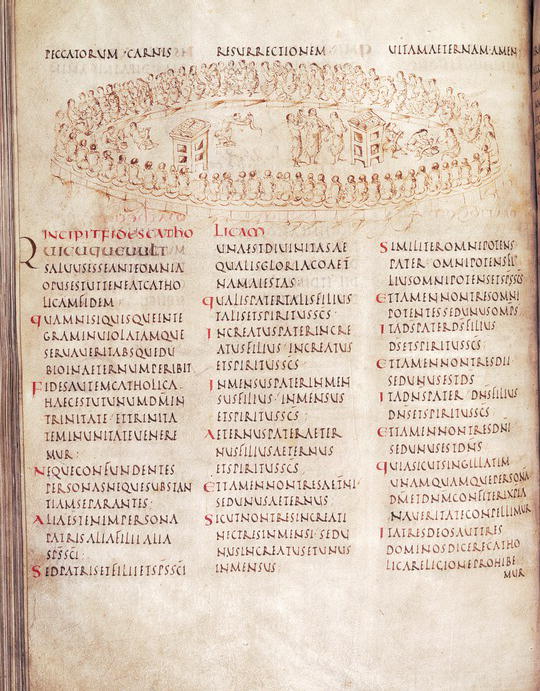

Plate 1 After the Fall. In an atmosphere of broken-down Romanity (represented by the clergy) a Frankish queen teaches her sons how to use the throwing-axe – a useful skill in a world of the blood feud. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912): The Education of the Children of Clotilde and Clovis, oil on panel, 1868. Private Collection / Photo © Christie’s Images / The Bridgeman Art Library