Chapter 2

Divisibility & Primes

There is a category of problems on the GRE that tests what could broadly be referred to as “Number Properties.” These questions are focused on a very important subset of numbers known as integers. Before we explore divisibility any further, it will be necessary to understand exactly what integers are and how they function.

Integers are whole numbers. That means that they are numbers that do not have any decimals or fractions attached. Some people think of them as counting numbers, that is, 1, 2, 3…etc. Integers can be positive, and they can also be negative. For instance, −1, −2, −3…etc. are all integers as well. And there's one more important number that qualifies as an integer: 0.

So numbers such as 7, 15,003, −346, and 0 are all integers. Numbers such as 1.3, 3/4, and π are not integers.

Now let's look at the rules for integers when dealing with the four basic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

| integer + integer = always an integer | ex. 4 + 11 = 15 |

| integer − integer = always an integer | ex. −5 − 32 = −37 |

| integer × integer = always an integer | ex. 14 × 3 = 42 |

None of these properties of integers turn out to be very interesting. But what happens when we divide an integer by another integer? Well, 18 ÷ 3 = 6, which is an integer, but 12 ÷ 8 = 1.5, which is not an integer.

If an integer divides another integer and the result, or quotient, is an integer, you would say that the first number is divisible by the second. So 18 is divisible by 3 because 18 ÷ 3 equals an integer. On the other hand, you would say that 12 is NOT divisible by 8, because 12 ÷ 8 is not an integer.

Divisibility Rules

The Divisibility Rules are important shortcuts to determine whether an integer is divisible by 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10. You can always use your calculator to test divisibility, but these shortcuts will save you time.

An integer is divisible by:

2 if the integer is even.

12 is divisible by 2, but 13 is not. Integers that are divisible by 2 are called “even” and integers that are not are called “odd.” You can tell whether a number is even by checking to see whether the units (ones) digit is 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8. Thus, 1,234,567 is odd, because 7 is odd, whereas 2,345,678 is even, because 8 is even.

3 if the SUM of the integer's digits is divisible by 3.

72 is divisible by 3 because the sum of its digits is 9, which is divisible by 3. By contrast, 83 is not divisible by 3, because the sum of its digits is 11, which is not divisible by 3.

4 if the integer is divisible by 2 twice, or if the two-digit number at the end is divisible by 4.

28 is divisible by 4 because you can divide it by 2 twice and get an integer result (28 ÷ 2 = 14, and 14 ÷ 2 = 7). For larger numbers, check only the last two digits. For example, 23,456 is divisible by 4 because 56 is divisible by 4, but 25,678 is not divisible by 4 because 78 is not divisible by 4.

5 if the integer ends in 0 or 5.

75 and 80 are divisible by 5, but 77 and 83 are not.

6 if the integer is divisible by both 2 and 3.

48 is divisible by 6 since it is divisible by 2 (it ends with an 8, which is even) AND by 3 (4 + 8 = 12, which is divisible by 3).

8 if the integer is divisible by 2 three times in succession, or if the three-digit number at the end is divisible by 8.

32 is divisible by 8 since you can divide it by 2 three times and get an integer result (32 ÷ 2 = 16, 16 ÷ 2 = 8, and 8 ÷ 2 = 4). For larger numbers, check only the last 3 digits. For example, 23,456 is divisible by 8 because 456 is divisible by 8, whereas 23,556 is not divisible by 8 because 556 is not divisible by 8.

9 if the sum of the integer's digits is divisible by 9.

4,185 is divisible by 9 since the sum of its digits is 18, which is divisible by 9. By contrast, 3,459 is not divisible by 9, because the sum of its digits is 21, which is not divisible by 9.

10 if the integer ends in 0.

670 is divisible by 10, but 675 is not.

The GRE can also test these divisibility rules in reverse. For example, if you are told that a number has a ones digit equal to 0, you can infer that that number is divisible by 10. Similarly, if you are told that the sum of the digits of x is equal to 21, you can infer that x is divisible by 3 but NOT by 9.

Note also that there is no rule listed for divisibility by 7. The simplest way to check for divisibility by 7, or by any other number not found in this list, is to use the calculator.

Check Your Skills

1. Is 123,456,789 divisible by 2?

2. Is 732 divisible by 3?

3. Is 989 divisible by 9?

4. Is 4,578 divisible by 4?

5. Is 4,578 divisible by 6?

6. Is 603,864 divisible by 8?

Answers can be found on page 53.

Factors

Continue to explore the question of divisibility by asking the question: What numbers is 6 divisible by? Questions related to divisibility are only interested in positive integers, so you really only have six possible numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. You can test to see which numbers 6 is divisible by:

| 6 ÷ 1 = 6 | Any number divided by 1 equals itself, so an integer divided by 1 will be an integer. |

|

|

| 6 ÷ 6 = 1 | Any number divided by itself equals 1, so an integer is always divisible by itself. |

So 6 is divisible by 1, 2, 3, and 6. That means that 1, 2, 3, and 6 are factors of 6. There are a variety of ways you might see this relationship expressed on the GRE:

| 2 is a factor of 6. | 6 is a multiple of 2. |

| 2 is a divisor of 6. | 6 is divisible by 2. |

| 2 divides 6. | 2 goes into 6. |

Sometimes it will be necessary to find the factors of a number in order to answer a question. An easy way to find all the factors of a small number is to use factor pairs. Factor pairs for any integer are the pairs of factors that, when multiplied together, yield that integer.

Here's a step-by-step way to find all the factors of the number 60 using a factor pairs table:

- Make a table with two columns labeled “Small” and “Large.”

- Start with 1 in the small column and 60 in the large column. (The first set of factor pairs will always be 1 and the number itself.)

Small Large 1 60 2 30 3 20 4 15 5 12 6 10 - The next number after 1 is 2. If 2 is a factor of 60, then write “2” underneath the “1” in your table. It is, so divide 60 by 2 to find the factor pair: 60 ÷ 2 = 30. Write “30” in the large column.

- The next number after 2 is 3. Repeat this process until the numbers in the small and the large columns run into each other. In this case, 6 and 10 are a factor pair. But 7, 8, and 9 are not factors of 60, and the next number after 9 is 10, which appears in the large column, so you can stop.

The advantage of using this method, as opposed to thinking of factors and listing them out, is that this is an organized, methodical approach that makes it easier to find every factor of a number quickly. Let's practice. (This is also a good opportunity to practice your long division.)

Check Your Skills

7. Find all the factors of 90.

8. Find all the factors of 72.

9. Find all the factors of 105.

10. Find all the factors of 120.

Answers can be found on pages 53–54.

Prime Numbers

Let's backtrack a little bit and try finding the factors of another small number: 7. The only possibilities are the positive integers less than or equal to 7, so let's check every possibility.

| 7 ÷ 1 = 7 | Every number is divisible by 1—no surprise there! | |

| 7 ÷ 2 = 3.5 |  |

|

| 7 ÷ 3 = 2.33… | The number 7 is not divisible by any integer besides 1 and itself. | |

| 7 ÷ 4 = 1.75 | ||

| 7 ÷ 5 = 1.4 | ||

| 7 ÷ 6 = 1.16… | ||

| 7 ÷ 7 = 1 | Every number is divisible by itself—boring! |

So 7 only has two factors—1 and itself. Numbers that only have two factors are known as prime numbers. As you will see, prime numbers play a very important role in answering questions about divisibility. Because they're so important, it's critical that you learn to identify what numbers are prime and what numbers aren't.

The prime numbers that appear most frequently on the test are prime numbers less than 20. They are 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, and 19. Two things to note about this list: 1 is not prime, and out of all the prime numbers, 2 is the only even prime number.

The number 2 is prime because it has only two factors—1 and itself. The reason that it's the only even prime number is that every other even number is also divisible by 2, and thus has another factor besides 1 and itself. For instance, you can immediately tell that 12,408 isn't prime, because we know that it has at least one factor besides 1 and itself: 2.

So every positive integer can be placed into one of two categories—prime or not prime:

| Primes | Non-Primes |

| 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, etc. | 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, etc. |

| exactly two factors: 1 and itself | more than two factors |

| ex. 7 = 1 × 7 | ex. 6 = 1 × 6 |

|

and 6 = 2 × 3 |

| only one factor pair | more than two factors and |

| more than one factor pair |

Check Your Skills

11. List all the prime numbers between 20 and 50.

The answer can be found on page 54.

Prime Factorization

Take another look at 60. When you found the factor pairs of 60, you saw that it had 12 factors and 6 factor pairs.

| 60 = 1 × 60 | Always the first factor pair—boring! | |

| and 2 × 30 |  |

|

| and 3 × 20 | ||

| and 4 × 15 | There are 5 other factor pairs—interesting! Look at these in a little more detail. | |

| and 5 × 12 | ||

| and 6 × 10 |

From here on, pairs will be referred to as boring and interesting factor pairs. These are not technical terms, but the boring factor pair is the factor pair that involves 1 and the number itself. All other pairs are interesting pairs. Keep reading to see why!

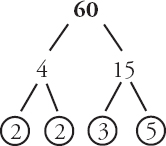

Examine one of these factor pairs—4 × 15. One way to think about this pair is that 60 breaks down into 4 and 15. One way to express this relationship visually is to use a factor tree:

Now, the question arises—can you go further? Sure! Neither 4 nor 15 is prime, which means they both have factor pairs that you might find interesting. For example, 4 breaks down into 2 × 2, and 15 breaks down into 3 × 5:

Can you break it down any further? Not with interesting factor pairs. You could say that 2 = 2 × 1, for instance, but that doesn't provide you any new information. The reason you can't go any further is that 2, 2, 3, and 5 are all prime numbers. Prime numbers only have one boring factor pair. So when you find a prime factor, you will know that that branch of your factor tree has reached its end. You can go one step further and circle every prime number as you go, reminding you that you the branch can't break down any further. The factor tree for 60 would look like this:

So after breaking down 60 into 4 and 15, and breaking 4 and 15 down, you end up with 60 equals 2 × 2 × 3 × 5.

What if you start with a different factor pair of 60? Create a factor tree for 60 in which the first breakdown you make is 6 × 10:

According to this factor tree 60 equals 2 × 3 × 2 × 5. Notice that, even though they're in a different order, this is the same group of prime numbers as before. In fact, any way you break down 60, you will end up with the same prime factors: two 2’s, one 3, and one 5. Another way to say this is that 2 × 2 × 3 × 5 is the prime factorization of 60.

One way to think about prime factors is that they are the DNA of a number. Every number has a unique prime factorization. The only number that can be written as 2 × 2 × 3 × 5 is 60. Breaking down numbers into their prime factors is the key to answering many divisibility problems.

As you proceed through the chapter, pay special attention to what prime factors can tell you about a number and some different types of questions the GRE may ask. But because the prime factorization of a number is so important, first you need a fast, reliable way to find the prime factorization of any number.

A factor tree is the best way to find the prime factorization of a number. A number like 60 should be relatively straightforward to break down into primes, but what if you need the prime factorization of 630?

For large numbers, it's often best to start with the smallest prime factors and work your way toward larger primes. This is why it's good to know your divisibility rules!

Take a second to try on your own, then continue through the explanation.

Start by finding the smallest prime number that 630 is divisible by. The smallest prime number is 2. Because 630 is even, it must be divisible by 2: 630 ÷ 2 = 315. So your first breakdown of 630 is into 2 and 315:

Now you still need to factor 315. It's not even, so it's not divisible by 2. Is it divisible by 3? If the digits of 315 add up to a multiple of 3, it is. Because 3 + 1 + 5 = 9, which is a multiple of 3, then 315 is divisible by 3: 315 ÷ 3 = 105. Your factor tree now looks like this:

If 315 was not divisible by 2, then 105 won't be either (the reason for this will be discussed later), but 105 might still be divisible by 3. Because 1 + 0 + 5 = 6, then 105 is divisible by 3: 105 ÷ 3 = 35. Your tree now looks like this:

Since 35 is not divisible by 3 (3 + 5 = 8, which is not a multiple of 3), the next number to try is 5. Because 35 ends in a 5, it is divisible by 5: 35 ÷ 5 = 7. Your tree now looks like this:

Every number on the tree has now been broken down as far as it can go. So the prime factorization of 630 is 2 × 3 × 3 × 5 × 7.

Alternatively, you could have split 630 into 63 and 10, since it's easy to see that 630 is divisible by 10. Then you would proceed from there. Either way will get you to the same set of prime factors.

Now it's time to get a little practice doing prime factorizations.

Check Your Skills

12. Find the prime factorization of 90.

13. Find the prime factorization of 72.

14. Find the prime factorization of 105.

15. Find the prime factorization of 120.

Answers can be found on pages 54–55.

The Factor Foundation Rule

This discussion begins with the factor foundation rule. The factor foundation rule states that if a is divisible by b, and b is divisible by c, then a is divisible by c as well. In other words, if you know that 12 is divisible by 6, and 6 is divisible by 3, then 12 is divisible by 3 as well.

This rule also works in reverse to a certain extent. If d is divisible by two different primes, e and f, d is also divisible by e × f. In other words, if 20 is divisible by 2 and by 5, then 20 is also divisible by 2 × 5, which is 10.

Another way to think of this rule is that divisibility travels up and down the factor tree. Let's walk through the factor tree of 150. Break it down, and then build it back up.

Because 150 is divisible by 10 and by 15, then 150 is also divisible by everything that 10 and 15 are divisible by. Because 10 is divisible by 2 and by 5, then 150 is also divisible by 2 and 5. Because 15 is divisible by 3 and by 5, then 150 is also divisible by 3 and 5. Taken all together, the prime factorization of 150 is 2 × 3 × 5 × 5. You could represent that information like this:

Think of prime factors as building blocks. In the case of 150, you have one 2, one 3, and two 5’s at your disposal to build other factors of 150. In the first example, you went down the tree—from 150 down to 10 and 15, and then down again to 2, 5, 3, and 5. But you can also build upwards, starting with the four building blocks. For instance, 2 × 3 = 6, and 5 × 5 = 25, so your tree could also look like this:

(Even though 5 and 5 are not different primes, 5 appears twice on 150’s tree. So you are allowed to multiply those two 5’s together to produce another factor of 150, namely 25.)

The tree above isn't even the only other possibility. These are all trees that you could build using different combinations of the prime factors.

You began with four prime factors of 150: 2, 3, 5 and 5. But you were able to build different factors by multiplying 2, 3, or even all 4 of those primes together in different combinations. As it turns out, all of the factors of a number (except for the number 1) can be built with different combinations of its prime factors.

The Factor/Prime Factorization Connection

Take one more look at the number 60 and its factors. Specifically, look at the prime factorizations of all the factors of 60:

All the factors of 60 are just different combinations of the prime numbers that make up the prime factorization of 60. To say this another way, every factor of a number can be expressed as the product of a combination of its prime factors. Take a look back at your work for Check Your Skills questions #7–10 and #12–15. Break down all the factor pairs from the first section into their prime factors. This relationship between factors and prime factors is true of every number.

Now that you know why prime factors are so important, it's time for the next step. An important skill on the GRE is to take the given information in a question and go further with it. For example, if a question tells you that a number n is even, what else do you know about it? Every even number is a multiple of 2, so n is a multiple of 2. These kinds of inferences often provide crucial information necessary to correctly solving problems.

So far, you've been finding factors and prime factors of numbers—but the GRE will sometimes ask divisibility questions about variables. In the next section, the discussion of divisibility will bring variables into the picture. But first, recap what you've learned so far and what tools you'll need going forward:

- If a is divisible by b, and b is divisible by c, then a is divisible by c as well (e.g., 100 is divisible by 20, and 20 is divisible by 4, so 100 is divisible by 4 as well).

- If d has e and f as prime factors, d is also divisible by e × f (e.g., 90 is divisible by 5 and by 3, so 90 is also divisible by 5 × 3 = 15). You can let e and f be the same prime, as long as there are at least two copies of that prime in d’s factor tree. (e.g., 98 has two 7’s in its factors, and so is divisible by 49).

- Every factor of a number (except the number 1) is either prime or the product of a different combination of that number's prime factors. For example, 30 = 2 × 3 × 5. Its factors are 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 (2 × 3), 10 (2 × 5), 15 (3 × 5), and 30 (2 × 3 × 5).

- To find all the factors of a number in an easy, methodical way, set up a factor pairs table.

- To find all the prime factors of a number, use a factor tree. With larger numbers, start with the smallest primes and work your way up to larger primes.

Check Your Skills

16. The prime factorization of a number is 3 × 5. What is the number and what are all of its factors?

17. The prime factorization of a number is 2 × 5 × 7. What is the number and what are all of its factors?

18. The prime factorization of a number is 2 × 3 × 13. What is the number and what are all of its factors?

Answers can be found on pages 55–56.

Unknown Numbers and Divisibility

Say that you are told some unknown positive number x is divisible by 6. How can you represent this on paper? There are many ways, depending on the problem. You could say that you know that x is a multiple of 6, or you could say that x = 6 × an integer. You could also represent the information with a factor tree. Careful though—although you've had a lot of practice drawing factor trees, there is one important difference now that you're dealing with an unknown number. You know that x is divisible by 6, but x may be divisible by other numbers as well. You have to treat what they have told you as incomplete information, and remind yourselves there are other things about x you don't know. To represent that on the page, your factor tree could look like this:

Now the question becomes—what else do you know about x? If a question on the GRE told you that x is divisible by 6, what could you definitely say about x? Take a look at these three statements, and for each statement, decide whether it must be true, whether it could be true, or whether it cannot be true.

I. x is divisible by 3

II. x is even

III. x is divisible by 12

Deal with each statement one at a time, beginning with Statement I—x is divisible by 3. One approach to take here is to think about the multiples of 6. If x is divisible by 6, then you know that x is a multiple of 6. List out the first several multiples of 6, and see if they're divisible by 3.

At this point, you can be fairly certain that x is divisible by 3. In fact, listing out possible values of a variable is often a great way to begin answering a question in which you don't know the value of the number you are asked about.

But can you do better than say you're fairly certain x is divisible by 3? Is there a way to definitively say x must be divisible by 3? As it turns out, there is. Look at the factor tree for x again:

Remember, the ultimate purpose of the factor tree is to break numbers down into their fundamental building blocks: prime numbers. Now that the factor tree is broken down as far as it will go, you can apply the factor foundation rule. Thus, x is divisible by 6, and 6 is divisible by 3, so you can say definitively that x must be divisible by 3.

In fact, questions like this one are the reason so much time was spent discussing the factor foundation rule and the connection between prime factors and divisibility. Prime factors provide the foundation for a way to make definite statements about divisibility. With that in mind, look at Statement II.

Statement II says x is even. This question is about divisibility, so the question becomes, what is the connection between divisibility and a number being even? Remember, an important part of this test is the ability to make inferences based on the given information.

What's the connection? Well, being even means being divisible by 2. So if you know that x is divisible by 2, then you can guarantee that x is even. Look at the factor tree:

You can once again make use of the factor foundation rule—6 is divisible by 2, so x must be divisible by 2 as well. And if x is divisible by 2, then x must be even as well.

That just leaves the final statement. Statement III says x is divisible by 12. Look at this question from the perspective of factor trees, and compare the factor tree of x with the factor tree of 12:

What would you have to know about x to guarantee that it is divisible by 12? Well, when 12 is broken down all the way, 12 is 2 × 2 × 3. Thus, 12’s building blocks are two 2’s and a 3. For x to be divisible by 12, it would have to also have two 2’s and one 3 among its prime factors. In other words, for x to be divisible by 12, it has to be divisible by everything that 12 is divisible by.

You need x to be divisible by two 2’s and one 3 in order to say it must be divisible by 12. But looking at your factor tree, there is only one 2 and only one 3. Because there is only one 2, you can't say that x must be divisible by 12. But then the question becomes, could x be divisible by 12? Think about the question for a second, and then keep reading.

The key to this question is the question mark that you put on x’s factor tree. That question mark should remind you that you don't know everything about x. Thus, x could have other prime factors. What if one of those unknown factors was another 2? Then the tree would look like this:

So if one of those unknown factors were a 2, then x would be divisible by 12. The key here is that you have no way of knowing for sure whether there is a 2. Thus, x may be divisible by 12, it may not. In other words, x could be divisible by 12.

To confirm this, go back to the multiples of 6. You still know that x must be a multiple of 6, so start by listing out the first several multiples and see whether they are divisible by 12.

Once again, some of the possible values of x are divisible by 12, and some aren't. The best you can say is that x could be divisible by 12.

Check Your Skills

For these statements, the following is true: x is divisible by 24. For each statement, say whether it must be true, could be true, or cannot be true.

19. x is divisible by 6

20. x is divisible by 9

21. x is divisible by 8

Answers can be found on pages 56–57.

Consider the following question, which has an additional twist this time. Once again, there will be three statements. Decide whether each statement must be true, could be true, or cannot be true. Answer this question on your own, then explore each statement one at a time on the next page.

x is divisible by 3 and by 10.

I. x is divisible by 2

II. is divisible by 15

III. x is divisible by 45

Before diving into the statements, spend a moment to organize the information the question has given you. You know that x is divisible by 3 and by 10, so you can create two factor trees to represent this information:

Now that you have your trees, get started with statement I. Statement I says that x is divisible by 2. The way to determine whether this statement is true should be fairly familiar by now—use the factor foundation rule. First of all, your factor trees aren't quite finished. Factor trees should always be broken down all the way until every branch ends in a prime number. Really, your factor trees should look like this:

Now you are ready to decide whether statement I is true. Because x is divisible by 10, and 10 is divisible by 2, therefore x is divisible by 2. Statement I must be true.

That brings you to statement II. This statement is a little more difficult. It also requires you to take another look at your factor trees. You have two separate trees, but they're giving you information about the same variable—x. Neither tree gives you complete information about x, but you do know a couple of things with absolute certainty. From the first tree, you know that x is divisible by 3, and from the second tree you know that x is divisible by 10—which really means you know that x is divisible by 2 and by 5. You can actually combine those two pieces of information and represent them on one factor tree, which would look like this:

Now you know three prime factors of x: 2, 3, and 5. Return to the statement. Statement II says that x is divisible by 15. What do you need to know to say that x must be divisible by 15? If you can guarantee that x has all the prime factors that 15 has, then you can guarantee that x is divisible by 15.

The number 15 breaks down into the prime factors 3 and 5. So to guarantee that x is divisible by 15, you need to know it's divisible by 3 and by 5. Looking back up at your factor tree, notice that x has both a 3 and a 5, which means that x is divisible by 15. Therefore, statement II must be true.

You can also look at this question more visually. Remember, prime factors are like building blocks—x is divisible by any combination of these prime factors. You can combine the prime factors in a number of different ways, as shown here:

Each of these factor trees can tell you different factors of x. But what's really important is what they have in common. No matter what way you combine the prime factors, each tree ultimately leads to 2 × 3 × 5, which equals 30. So you know that x is divisible by 30. And if x is divisible by 30, it is also divisible by everything 30 is divisible by. You know how to identify every number 30 is divisible by—use a factor pair table. The factor pair table of 30 looks like this:

| Small | Large |

| 1 | 30 |

| 2 | 15 |

| 3 | 10 |

| 5 | 6 |

Again, Statement II says that x is divisible by 15. Because x is divisible by 30, and 30 is divisible by 15, then x must be divisible by 15.

That brings you to Statement III. Statement III says that x is divisible by 45. What do you need to know to say that x must be divisible by 45? Build a factor tree of 45, which looks like this:

The number 45 is divisible by 3, 3, and 5. For x to be divisible by 45, you need to know that it has all the same prime factors. Does it?

The factorization of 45 has one 5 and two 3’s. Although x has a 5, you only know that x has one 3. That means that you can't say for sure that x is divisible by 45. However, x could be divisible by 45, because you don't know what the question mark contains. If it contains a 3, then x is divisible by 45. If it doesn't contain a 3, then x is not divisible by 45. Without more information, you can't say for sure either way. So statement III could be true.

Now it's time to recap what's been covered in this chapter. When dealing with questions about divisibility, you need a quick, accurate way to identify all the factors of a number. A factor pair table provides a reliable way to make sure you find every factor of a number.

Prime factors provide essential information about a number or variable. They are the fundamental building blocks of every number. In order for a number or variable to be divisible by another number, it must contain all the same prime factors that the other number contains. In the last example, you could definitely say that x was divisible by 15, because x contained one 3 and one 5. But you could not say that it was divisible by 45, because 45 has one 5 and two 3’s, but x only had one 5 and one 3.

Check Your Skills

For these statements, the following is true: x is divisible by 28 and by 15. For each statement, say whether it must be true, could be true, or cannot be true.

22. x is divisible by 14.

23. x is divisible by 20.

24. x is divisible by 24.

Answers can be found on pages 58.

Fewer Factors, More Multiples

Sometimes it is easy to confuse factors and multiples. The mnemonic “Fewer Factors, More Multiples” should help you remember the difference. Factors divide into an integer and are therefore less than or equal to that integer. Positive multiples, on the other hand, multiply out from an integer and are therefore greater than or equal to that integer.

Any integer only has a limited number of factors. For example, there are only four factors of 8: 1, 2, 4, and 8. By contrast, there is an infinite number of multiples of an integer. For example, the first five positive multiples of 8 are 8, 16, 24, 32, and 40, but you could go on listing multiples of 8 forever.

Factors, multiples, and divisibility are very closely related concepts. For example, 3 is a factor of 12. This is the same as saying that 12 is a multiple of 3, or that 12 is divisible by 3.

On the GRE, this terminology is often used interchangeably in order to make the problem seem harder than it actually is. Be aware of the different ways that the GRE can phrase information about divisibility. Moreover, try to convert all such statements to the same terminology. For example, all of the following statements say exactly the same thing:

| • 12 is divisible by 3 | • 3 is a divisor of 12, or 3 is a factor of 12 |

| • 12 is a multiple of 3 | • 3 divides 12 |

•  is an integer is an integer |

•  yields a remainder of 0 yields a remainder of 0 |

| • 12 = 3n, where n is an integer | • 3 “goes into” 12 evenly |

| • 12 items can be shared among 3 people so that each person has the same number of items. |

Another term that the GRE sometimes uses is “unique prime factor.” The distinction between a prime factor and a unique prime factor is best illustrated by an example. If you prime factor 12, you end up with two 2’s and one 3, but 12 only has two unique prime factors, 2 and 3, because the two 2’s are the same number. So 100 has 2 unique prime factors (2 and 5) just as 10 does.

Divisibility and Addition/Subtraction

If you add two multiples of 7, you get another multiple of 7. Try it: 35 + 21 = 56. This should make sense: (5 × 7) + (3 × 7) = (5 + 3) × 7 = 8 × 7.

Likewise, if you subtract two multiples of 7, you get another multiple of 7. Try it: 35 − 21 = 14. Again, it's clear why: (5 × 7) − (3 × 7) = (5 − 3) × 7 = 2 × 7.

This pattern holds true for the multiples of any integer N. If you add or subtract multiples of N, the result is a multiple of N. You can restate this principle using any of the disguises above: for instance, if N is a divisor of x and of y, then N is a divisor of x + y.

Remainders

The number 17 is not divisible by 5. When you divide 17 by 5, using long division, you get a remainder: a number left over. In this case, the remainder is 2, as shown here:

You can also write that 17 is 2 more than 15, or 2 more than a multiple of 5. In other words, you can write 17 = 15 + 2 = 3 × 5 + 2. Every number that leaves a remainder of 2 after it is divided by 5 can be written this way: as a multiple of 5, plus 2.

On simpler remainder problems, it is often easiest to pick numbers. Simply add the desired remainder to a multiple of the divisor. For instance, if you need a number that leaves a remainder of 4 after division by 7, first pick a multiple of 7, such as 14. Then add 4 to get 18, which satisfies the requirement (18 = 7 × 2 + 4).

A remainder is defined as the integer portion of the dividend (or numerator) that is not evenly divisible by the divisor (or denominator). Here is an example written in fractional notation:

The quotient is the resulting integer portion that can be divided out (in this case, the quotient is 5). Note that the dividend, divisor, quotient, and remainder will always be integers. Sometimes, the quotient may be zero! For instance, when 3 is divided by 5, the remainder is 3 but the quotient is 0 (because 0 is the biggest multiple of 5 that can be divided out of 3).

Algebraically, this relationship can be written as the Remainder Formula:

This framework is often easiest to use on GRE problems when you multiply through by the divisor N:

Again, remember that x, Q, N, and R must all be integers. It should also be noted that R must be equal to or greater than 0, but less than N (the divisor). This is discussed below.

Range of Possible Remainders

When you divide an integer by 7, the remainder could be 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Notice that you cannot have a negative remainder or a remainder larger than 7, and that you have exactly 7 possible remainders. You can see these remainders repeating themselves on the Remainder Ruler:

This pattern can be generalized. When you divide an integer by a positive integer N, the possible remainders range from 0 to (N − 1). There are thus N possible remainders. Negative remainders are not possible, nor are remainders equal to or larger than N.

If a ÷ b yields a remainder of 3, c ÷ d yields a remainder of 4, and a, b, c, and d are all integers, what is the smallest possible value for b + d?

Since the remainder must be smaller than the divisor, 3 must be smaller than b. Since b must be an integer, then b is at least 4. Similarly, 4 must be smaller than d, and d must be an integer, so d must be at least 5. Therefore, the smallest possible value for b + d is 4 + 5 = 9.

Remainder of 0

If x divided by y yields a remainder of 0 (commonly referred to as “no remainder”), then x is divisible by y. Conversely, if x is divisible by y, then x divided by y yields a remainder of 0 (or “no remainder”).

Similarly, if x divided by y yields a remainder greater than 0, then x is not divisible by y, and vice versa.

Arithmetic with Remainders

Two useful tips for arithmetic with remainders, if you have the same divisor throughout:

- You can add and subtract remainders directly, as long as you correct excess or negative remainders. “Excess remainders” are remainders larger than or equal to the divisor. To correct excess or negative remainders, just add or subtract the divisor. For instance, if x leaves a remainder of 4 after division by 7, and y leaves a remainder of 2 after division by 7, then x + y leaves a remainder of 4 + 2 = 6 after division by 7. You do not need to pick numbers or write algebraic expressions for x and y. Simply write R4 + R2 = R6.

- If x leaves a remainder of 4 after division by 7 and z leaves a remainder of 5 after division by 7, then adding the remainders together yields 9. This number is too high, however. The remainder must be non-negative and less than 7. You can take an additional 7 out of the remainder, because 7 is the excess portion. The correct remainder is thus R4 + R5 = R9 = R2 (subtracting a 7 out).

- With the same x and z, subtraction of the remainders gives −1, which is also an unacceptable remainder (it must be non-negative). In this case, add an extra 7 to see that x − z leaves a remainder of 6 after division by 7. Using R's, you can write R4 − R5 = R(−1) = R6 (adding a 7 in).

- You can multiply remainders, as long as you correct excess remainders at the end.

- Again, if x has a remainder of 4 upon division by 7 and z has a remainder of 5 upon division by 7, then 4 × 5 gives 20. Two additional 7’s can be taken out of this remainder, so x × z will have remainder 6 upon division by 7. In other words, (R4)(R5) = R20 = R6 (taking out two 7’s). You can prove this by again picking x = 25 and z = 12 (try the algebraic method on your own!):

Check Your Skills

25. What is the remainder when 13 is divided by 6?

26. What's the first double-digit number that results in a remainder of 4 when divided by 5?

27. If x has a remainder of 4 when divided by 9 and y has a remainder of 3 when divided by 9, what's the remainder when x + y is divided by 9?

28. Using the example from #27, what's the remainder when xy is divided by 9?

Answers can be found on pages 58–59.

Check Your Skills Answer Key

1. No: Is 123,456,789 divisible by 2?

123,456,789 is an odd number, because it ends in 9, so 123,456,789 is not divisible by 2.

2. Yes: Is 732 divisible by 3?

The digits of 732 add up to a multiple of 3 (7 + 3 + 2 = 12), so 732 is divisible by 3.

3. No: Is 989 divisible by 9?

The digits of 989 do not add up to a multiple of 9 (9 + 8 + 9 = 26), so 989 is not divisible by 9.

4. No: Every whole hundred is divisible by 4, so you only need to check the amount “left over.” Since 78 is not divisible by 4, then 4,578 is not divisible by 4.

5. Yes: Any number divisible by both 2 and 3 is divisible by 6. So 4,578 must be divisible by 2, because it ends in an even number. It also must be divisible by 3, because the sum of its digits is a multiple of 3 (4 + 5 + 7 + 8 = 24). Therefore, 4,578 is divisible by 6.

6. Yes: Easiest to use your calculator for this one: 603,864 ÷ 8 = 75,483 with no remainder.

Alternatively, evaluate the three-digit number at the end; every whole thousand is divisible by 8, so you only need to check the amount “left over.” 864 is divisible by 8 because 864 = 800 + 64 and both 800 and 64 are multiples of 8.

7. Find all the factors of 90.

| Small | Large |

| 1 | 90 |

| 2 | 45 |

| 3 | 30 |

| 5 | 18 |

| 6 | 15 |

| 9 | 10 |

8. Find all the factors of 72.

| Small | Large |

| 1 | 72 |

| 2 | 36 |

| 3 | 24 |

| 4 | 18 |

| 6 | 12 |

| 8 | 9 |

9. Find all the factors of 105.

| Small | Large |

| 1 | 105 |

| 3 | 35 |

| 5 | 21 |

| 7 | 15 |

10. Find all the factors of 120.

| Small | Large |

| 1 | 120 |

| 2 | 60 |

| 3 | 40 |

| 4 | 30 |

| 5 | 24 |

| 6 | 20 |

| 8 | 15 |

| 10 | 12 |

11. List all the prime numbers between 20 and 50.

23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, and 47

12. Find the prime factorization of 90.

13. Find the prime factorization of 72.

14. Find the prime factorization of 105.

15. Find the prime factorization of 120.

16. The prime factorization of a number is 3 × 5. What is the number and what are all its factors?

3 × 5 = 15

| Small | Large |

| 1 | 15 |

| 3 | 5 |

17. The prime factorization of a number is 2 × 5 × 7. What is the number and what are all its factors?

2 × 5 × 7 = 70

18. The prime factorization of a number is 2 × 3 × 13. What is the number and what are all its factors?

2 × 3 × 13 = 78

For questions 19–21, x is divisible by 24.

19. Must Be True: x is divisible by 6

For x to be divisible by 6, you need to know that it contains the same prime factors as 6, which contains a 2 and a 3. Since x also contains a 2 and a 3, x must therefore be divisible by 6.

20. Could Be True: x is divisible by 9

For x to be divisible by 9, you need to know that it contains the same prime factors as 9, which contains two 3’s. However, x only contains one 3 that you know of. But the question mark means x may have other prime factors, and may contain another 3. For this reason, x could be divisible by 9.

21. Must Be True: x is divisible by 8

For x to be divisible by 8, you need to know that it contains the same prime factors as 8, which contains three 2’s. Since x also contains three 2’s, x must therefore be divisible by 8.

For questions 22–24, x is divisible by 28 and by 15.

22. Must Be True: x is divisible by 14.

For x to be divisible by 14, you need to know that it contains the same prime factors as 14, which contains a 2 and a 7. Because x also contains a 2 and a 7, x must therefore be divisible by 14.

23. Must Be True: x is divisible by 20.

For x to be divisible by 20, you need to know that it contains the same prime factors as 20, which contains two 2’s and one 5. Since x also contains two 2’s and a 5, x must therefore be divisible by 20.

24. Could Be True: x is divisible by 24.

For x to be divisible by 24, you need to know that it contains the same prime factors as 24, which contains three 2’s and one 3. However x contains one 3, but only two 2’s that you know of. But the question mark means x may have other prime factors, and may contain another 2. For this reason, x could be divisible by 24.

25. 1: The number 6 goes into 13 two full times, which means the quotient is 2. Therefore, 2 × 6 = 12, and 12 + 1 = 13. The remainder is 1.

26. 14: For a number to result in a remainder of 4 when divided by 5, it has to be equal to a multiple of 5, plus 4. The first of these is 4 (5 × 0 + 4 = 4), the second is 9 (5 × 1 + 4 = 9), and the third is 14 (5 × 2 + 4). Thus, 14 is the first double-digit number that produces the required remainder.

27. 7: Using the Remainder Formula:

Therefore, x + y = 9 (Q + Q') + 7 and the remainder is 7.

28. 3: Again using the Remainder Formula:

Therefore, xy = (9Q + 4)(9Q' + 3) = 81QQ' + 27Q + 36Q' + 12.

Since each of the terms except 12 is divisible by 9, and a 9 can be removed from 12, the correct answer is 12 − 9 = 3.

Problem Set

For problems #1–10, use prime factorization, if appropriate, to answer each question: Yes, No, or Cannot Be Determined. If your answer is Cannot Be Determined, use two numerical examples to show how the problem could go either way. All variables in problems 1–12 are assumed to be positive integers unless otherwise indicated.

1. If a is divided by 7 or by 18, an integer results. Is  an integer?

an integer?

2. If 80 is a factor of r, is 15 a factor of r?

3. If 7 is a factor of n and 7 is a factor of p, is n + p divisible by 7?

4. If 8 is not a factor of g, is 8 a factor of 2g?

5. If j is divisible by 12 and 10, is j divisible by 24?

6. If 12 is a factor of xyz, is 12 a factor of xy?

7. If 6 is a divisor of r and r is a factor of s, is 6 a factor of s?

8. If 24 is a factor of h and 28 is a factor of k, must 21 be a factor of hk?

9. If 6 is not a factor of d, is 12d divisible by 6?

10. If 60 is a factor of u, is 18 a factor of u?

11.

| Quantity A | Quantity B | |

| The number of distinct prime factors of 40 | The number of distinct prime factors of 50 |

12.

| Quantity A | Quantity B | |

| The product of 12 and an even prime number | The sum of the greatest four factors of 12 |

13.

x = 20, y = 32, and z = 12

| Quantity A | Quantity B | |

| The remainder when x is divided by z | The remainder when y is divided by z |

14. If a and b are positive integers such that the remainder is 4 when a is divided by b, what is the smallest possible value of a + b?

15. If  has a remainder of 0 and

has a remainder of 0 and  has a remainder of 3, what is the remainder of

has a remainder of 3, what is the remainder of  ?

?

Solutions

1. Yes: If a is divisible by 7 and by 18, its prime factors include 2, 3, 3, and 7, as indicated by the factor tree to the right. Therefore, any integer that can be constructed as a product of any of these prime factors is also a factor of a. Thus, 42 = 2 × 3 × 7. Therefore, 42 is also a factor of a.

2. Cannot Be Determined: If r is divisible by 80, its prime factors include 2, 2, 2, 2, and 5, as indicated by the factor tree to the right. Therefore, any integer that can be constructed as a product of any of these prime factors is also a factor of r. Thus, 15 = 3 × 5. Since the prime factor 3 is not in the factor tree, you cannot determine whether 15 is a factor of r. As numerical examples, you could take r = 80, in which case 15 is not a factor of r, or r = 240, in which case 15 is a factor of r.

3. Yes: If two numbers are both multiples of the same number, then their sum is also a multiple of that same number. Since n and p share the common factor 7, the sum of n and p must also be divisible by 7.

4. Cannot Be Determined: In order for 8 to be a factor of 2g, you would need two more 2’s in the factor tree. By the Factor Foundation Rule, g would need to be divisible by 4. You know that g is not divisible by 8, but there are certainly integers that are divisible by 4 and not by 8, such as 4, 12, 20, 28, etc. However, while you cannot conclude that g is not divisible by 4, you cannot be certain that g is divisible by 4, either. As numerical examples, you could take g = 5, in which case 8 is not a factor of 2g, or g = 4, in which case 8 is a factor of 2g.

5. Cannot Be Determined: If j is divisible by 12 and by 10, its prime factors include 2, 2, 3, and 5, as indicated by the factor tree to the right. There are only two 2’s that are definitely in the prime factorization of j, because the 2 in the prime factorization of 10 may be redundant—that is, it may be the same 2 as one of the 2’s in the prime factorization of 12.

Thus, 24 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 3. There are only two 2’s in the prime box of j; 24 requires three 2’s. Therefore, 24 is not necessarily a factor of j.

As another way to prove that you cannot determine whether 24 is a factor of j, consider 60. The number 60 is divisible by both 12 and 10. However, it is not divisible by 24. Therefore, j could equal 60, in which case it is not divisible by 24. Alternatively, j could equal 120, in which case it is divisible by 24.

6. Cannot Be Determined: If xyz is divisible by 12, its prime factors include 2, 2, and 3, as indicated by the factor tree to the right. Those prime factors could all be factors of x and y, in which case 12 is a factor of xy. For example, this is the case when x = 20, y = 3, and z = 7. However, x and y could be prime or otherwise not divisible by 2, 2, and 3, in which case xy is not divisible by 12. For example, this is the case when x = 5, y = 11, and z = 24.

7. Yes: By the Factor Foundation Rule, if 6 is a factor of r and r is a factor of s, then 6 is a factor of s.

8. Yes: By the Factor Foundation Rule, all the factors of both h and k must be factors of the product, hk. Therefore, the factors of hk include 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, and 7, as shown in the combined factor tree to the right. Thus, 21 = 3 × 7. Both 3 and 7 are in the tree. Therefore, 21 is a factor of hk.

9. Yes: The fact that d is not divisible by 6 is irrelevant in this case. Since 12 is divisible by 6, 12d is also divisible by 6.

10. Cannot Be Determined: If u is divisible by 60, its prime factors include 2, 2, 3, and 5, as indicated by the factor tree to the right. Therefore, any integer that can be constructed as a product of any of these prime factors is also a factor of u. Thus, 18 = 2 × 3 × 3. Since there is only one 3 in the factor tree, you cannot determine whether or not 18 is a factor of u. As numerical examples, you could take u = 60, in which case 18 is not a factor of u, or u = 180, in which case 18 is a factor of u.

11. (C): The prime factorization of 40 is 2 × 2 × 2 × 5. So 40 has 2 distinct prime factors: 2 and 5. The prime factorization of 50 is 5 × 5 × 2, so 50 also has two distinct prime factors: 2 and 5. Therefore, the two quantities are equal.

12. (B): Simplify Quantity A first. There is only one even prime number: 2. Therefore, Quantity A is 12 × 2 = 24.

| Quantity A | Quantity B | |

| The product of 12 and an even prime number = | The sum of the greatest four factors of 12 = | |

| 12 × 2 = 24 | 12 + 6 + 4 + 3 = 25 |

The four greatest factors of 12 are 12, 6, 4 and 3. Thus, 12 + 6 + 4 + 3 = 25. Therefore, Quantity B is greater.

13. (C): When 20 is divided by 12, the result is a quotient of 1 and a remainder of 8 (12 × 1 + 8 = 20).

When 32 is divided by 12, the result is a quotient of 2 and a remainder of 8 (12 × 2 + 8 = 32).

x = 20, y = 32, and z = 12

| Quantity A | Quantity B | |

| 8 | 8 |

Therefore, the two quantities are equal.

14. 9: Since  has a remainder of 4, b must be at least 5 (remember, the remainder must always be smaller than the divisor). The smallest possible value for a is 4 (it could also be 9, 14, 19, etc.). Thus, the smallest possible value for a + b is 9.

has a remainder of 4, b must be at least 5 (remember, the remainder must always be smaller than the divisor). The smallest possible value for a is 4 (it could also be 9, 14, 19, etc.). Thus, the smallest possible value for a + b is 9.

15. 0: Because  has a remainder of 0, x is divisible by y. Therefore, xz will be divisible by y, and so will have a remainder of 0 when divided by y.

has a remainder of 0, x is divisible by y. Therefore, xz will be divisible by y, and so will have a remainder of 0 when divided by y.