3rd February 1876

There has been no light. Not for days now. We all live in darkness and pretend it is the most natural thing.

I admit very readily that there were days before when no light ever broke through onto London, but this darkness has been longer, and it has been darker. The gas is lit on the street at all hours, but it fails to illuminate much of anything. The only way to see what is before you is to set a candle to it, and always you are aware of the thick darkness all around that wants to put it out. It has been like this ever since the new family moved into the house across the street.

No children play in the street, not since they came. And even adults rush from the place as if they fear it terribly, as if the street itself is damned.

Well perhaps it is.

I think I’m the only one at the window these days, all the other glass up and down the street is shuttered up or the curtains have been drawn and remain so. It’s as if the eyes of the street are closed, and no one else is watching.

But I’m watching. I’m watching that house. I shan’t ever stop.

Our street, our Connaught Place, is not the grandest address by any means. The best perhaps that can be said about it is that beyond the thickness of our south walls lies the great expanse of Hyde Park and space and green, though the whole park has been covered in a thick black fog for some time now, and, so Nanny says, it is so dark that it is as if the world has ended at the Bayswater Road.

It has been so ever since they came. It is colder and harsher, the weather itself feels unkind, all the walls are frigid to the touch and they drip at times, so that much of the wallpaper through the house has grown blisters. And all of it, all of it, since they came.

It is a very secret family that arrived here on the night that Foulsham – the borough of rubbish – caught fire and was burnt to the ground. That fire was so fierce that it smoulders still. How many people were killed that night I do not know. It must have been so terrible to be there, but somehow the papers never talk of how many died. That was the night the family moved in, when a whole borough was wiped out and all that was left were ashes. Who mourns for them, I wonder? I do not suppose that it is a coincidence that the family arrived that night of all nights.

No one ever comes out of the front door. I think they must leave sometimes but the place looks so shuttered up. Twice only, to my excitement, in the deep of night, I have seen a young man with something flashing on his chest like a medal and with a shining brass helmet on his head, rushing out of the servants’ door on some business, and both times he was with a rather greasy fellow just behind him, as if that following person were not really a man at all but a shadow made somehow solid. I saw them only for the briefest of seconds when they came under the faint glow of the gas streetlamp. But when I tell Nanny or Mother, I am instructed to stop imagining things, to cease being so bothersome.

‘There is no one in that house,’ Mother tells me. ‘It is quite boarded up as you see. The Carringtons have had it shut up while they remain in the country to recover from their sudden illness. We hope that they are feeling better.’

‘There are people there, Mother, I’ve seen them.’

‘Stop it, Eleanor, I haven’t the time.’

It’s always more dirty around that house than any of the others along Connaught Place. It never used to be like that. It’s as if the dirt likes the house, as if it were somehow dirt’s home. I wonder what it is like inside. I never minded overly much about it when the Carringtons lived there, but now I find myself wondering about it most particularly.

I have begun to think that it notices, this new night of ours. It is watching. In fact I am sure of it. It is not just that it is dark outside – this new darkness is a thick darkness, it’s black clouds, it’s gas, it’s something alive. You must shoo it from a room.

I generally keep a pair of bellows with me when I’m at home, and I pump my bellows and I see the clouds of night marshalled and bullied by my bellows-wind. If I work the bellows hard, I can gather the night up and send it all into a corner where I see it writhe. I watch it panic. At last it rushes itself of a sudden out through a keyhole or under a door, or hides under my bed – then creeps out again to look over my shoulder when I’m sat at the window keeping my notes. Wherever it has been it leaves behind a slight stain. It darkens and discolours all.

I have begun to wonder if the night might actually report on me, on all of us. I do think little pieces of night rush back over the street and into the house there to tell tales. The night is surely thickest over there. And that house is darker than any other. It is there that the long night comes from, I’d swear to it. From there it gets everywhere. It’s in our hair, on our skin; it’s in our pockets and our thoughts; it’s on the mantelpiece and behind the door. Before putting on shoes you must turn them upside down and beat the night out of them. If you do that, sure enough a little black cloud comes trickling out. Stamp on that cloud. Stamp on it quick.

We have all been breathing the night in.

It does things to people, the new night. I have noticed it in my family, in the people all about us. In my things, even. This is what I have seen. Here is my tally:

1. Great Aunt Rowena (Father’s maiden aunt who lives around the corner from us in Connaught Square, she who is the most wealthy of all our family, and who Mother is always encouraging me to be nice to, though really I need no encouragement). Great Aunt complains increasingly of a stiffness. She never was exactly a fluid person to begin with but now she insists that her stiffness is overcoming her and that she barely bends at all. I thought little enough of this when Great Aunt Rowena last invited me over to tea. She’d set all her dolls out for us to play with, but then – at her beckoning, in a quiet moment when we were alone together and Pritchett her maid had gone away to fetch some more biscuits – I did cautiously knock upon one of her legs. The sound was almost terrifying; it was just like wood. ‘Oh, Aunt,’ I cried. ‘I’m as stiff as a post,’ she said. ‘Yes,’ I said and, very earnestly, ‘Oh yes you are indeed!’

2. My school desk in the school room, which always used to have four legs (as is most common with desks) now has five. I cannot say how it grew that other leg. Nanny says it has always been there but I know otherwise.

3. Father’s shaving brush, which always had handsome soft bristles on one side of it, has started to grow dark, thick, spiky hairs along its handle.

4. Uncle Randolph (Mother’s wayward brother – Father always refers to him in this way) is no longer engaged to Olivia Finch (I never liked her much myself). She has gone from London and is believed to be on the Continent. Mother said she ‘let him down terribly’ but I think I know the true reason. Uncle Randolph has fallen in love with a milk jug, which he keeps with him always. I have seen him whispering to the milk jug when he thinks no one is there, I even heard him calling it ‘My darling, my Liv-love,’ which was the ridiculous name he had formerly reserved for Olivia.

6. Mrs Glimsford (our housekeeper) has become flat-footed and she never used to be.

7. The brass fire extinguisher in the cupboard on my landing is getting taller. It has grown four inches.

BUT MOST OF ALL:

8. I do believe the music stand in my bedroom was once a servant from next door.

Oh, the poor music stand. That first night when the secret family moved in, I sent Martha out to fetch the unhappy thing. Now I stop myself, I catch myself as I write all this down. I pause for breath, and I wonder –

Could that really have happened? A person become a music stand?

I look at the music stand standing here beside me and cannot quite believe it. I try very hard to remember that night. I saw them walking down the street, such a strange group of people, like a circus troop, but no colour to them, only greyness and grimness. And the worst of it all was the tall old man in the long black hat.

The servant went up to him, to warn him about the Carringtons’ cholera and in return he took one look at her and at the flick of his fingers changed her from a person into … into an object, into this music stand. What a thing to happen! Oh! I stop again. And write this prayer.

I SO WANT IT ALL TO HAVE BEEN A DREAM. PLEASE MAY IT BE ONE. PLEASE GOD.

But I know it is not a dream.

I have inquired next door, at number 21, about the servant.

‘Excuse me,’ I said.

‘Yes?’ came the butler, a Mr Ogilvy I believe.

‘You had a servant, she was a maid of some sort.’

‘Yes?’

‘Quite short, I believe, with rather full cheeks.’

‘Do you mean Janey, Janey Cunliffe?’

‘I suppose I do. May I see her please?’

‘No you may not.’

‘Is she not inside? Is she too busy with her duties perhaps?’

‘What do you know of Janey Cunliffe, miss?’

‘Nothing really, only I should like to talk to her.’

‘Well and so should we, we have much to say to her in fact. Leaving her position with no warning. Sent out to do a small errand, and she never comes back. And some of the silver missing too, and an ormolu clock, well, well, yes indeed we should very much like to speak to Miss Janey Cunliffe. Very much.’

And that was the end of our conversation.

I do actually feel it is the servant, this poor music stand, this poor Janey Cunliffe.

‘Hello, dear,’ I say to it. ‘I hope to make you yourself once more. Truly I do. I have not forgotten you, Jane, even if everyone else has. (I shan’t call you Janey, if you don’t mind, it sounds too childish.)’

I put her on the windowsill so that she may look out.

Martha, the tweeny maid, fears to come near me since delivering the stand, as if I’m quite mad; she weeps a deal and says I’m mean to her. Even Nanny’s been a little odd of late, she comes less and less and spends her time in her room with her gilt-edged calf-skinned Bible and won’t go anywhere without it; she consults it, she whispers to it. (What a thing to wrap the Bible in, something’s skin, when you think about it that doesn’t seem right at all.) I don’t have many companions, I have no siblings and I am schooled here at home, so the loss of Nanny does make rather a gap in my social calendar.

And all of this, all this strangeness, is on account of the new neighbours across the way. I wonder if it is just our household that suffers so, or if others are likewise inconvenienced.

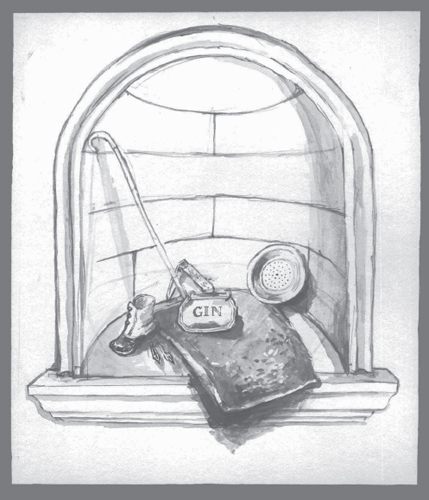

A Diseased Pair of Curtains With the Remnants of a Pelmet

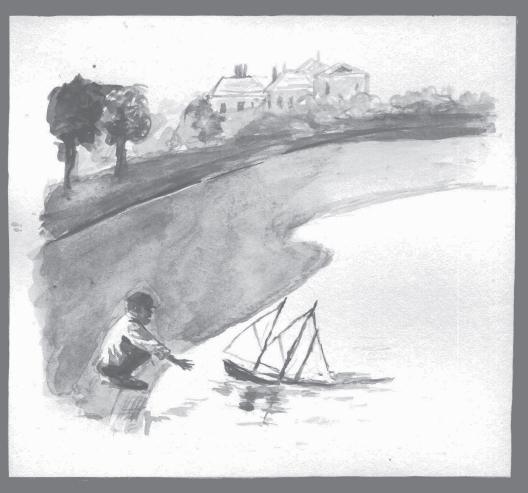

A Sinking Boat, the Round Pond, Kensington Gardens