‘Lucy, Lucy, Lucy. Lucy! Lucy! LUCY!’

‘Wake up!’

‘LUCY!’

‘Shut up!’

‘LUCY! LUCY!’

‘Rippit!’

I’d been at it again, they said, calling out in my sleep. Waking everyone up. Wasn’t right to do that. Wasn’t proper. Wasn’t London. We’re in London now, and must behave London-like. So then. Shut up in your sleep.

But whenever I was in sleep, I was looking for Lucy all over Foulsham, calling out for her but never finding her. And waking up in London, Foulsham seemed so far away and Lucy even further.

London. In London.

All my life I had wanted to be in London. And now, finally that I was here, in a London street, in a London house, I could summon no comfort from it. I was Clod Iremonger, London lingerer. London in my lungs. London in my eyes. Here was London, oh my ever-longed-for London.

I used to have a map of London in my old bedroom in Heap House. I should trace the streets with my fingers, never daring to hope I may one day live there. But I saw of it oh so little then, just a great smudge in the distance. But now, there I was, a Londoner. A Londoner perhaps, though not so much of it spilled into my ill head, but I caught it through windows whenever I could, though they said I must keep the curtains closed, still I stole small glimpses from this London address. I shall know you yet, I shall be a London one, shall I?

There is nowhere else for me to go. I cannot go back home.

Our home, old home, old place, disgraced and thrown over, blackened, cracked, forlorn, forgot, death place, dead home, death knell, pell mell, gone and gone and never ever to return. They pulled it down. And never will it up again.

Home of my people: no, nowhere.

I am most awfully without home.

How many died, my Lucy, my ever Lucy Pennant? She that I loved and loved me back. Scrap of a servant girl, my own everything. Gone and gone and gone. How many buried, burnt, smothered, put out, snuffed out, out of the game, gone under, killed, murdered, butchered, bled? How many bones, sacred bones, left? I’d pick up that dust. I’d look after it so.

Put me with the cinders. I’d be better left there.

How many that once were, are only silent now?

We’re off the map. Mapless, landless people. Extinct. First the dodo, then the great auk, then the piebald Forlichingham Terrier, then Foulsham itself. And yet I breathe still. Shouldn’t. Most highly improper that I do. So wish that I didn’t. Some rats always find a way. You demolish a slum, the slum pushes up somewhere else. If ever there was a family that should shake off death, that should ignore it and grin at it, it is mine.

For I am, and ever shall be whilst I breathe, an Iremonger.

Far rather I should not be and rip myself in two.

Should much rather be dead.

But am not.

I’d even extinguish myself. And they know, my family, and so they watch me, they watch me always. How I am looked at and watched over in my nightshirt that may as well be my prison uniform. What’s to live for, after all, in this Lucy-less world? No Lucy today or tomorrow, no Lucy next week, no Lucy next month, next year no no Lucy. No red any more ever again, not the exact right red that I long for with such an ache. My fingers in her hair. No freckles that I care for. As if each freckle were a full stop. And there are only full stops. I can’t be whole any longer. Oh, Lucy gone and dead on me. What’s a fellow to do?

When will the ache stop?

Oh never let it stop.

My family filled me with hate. Well then let them, I’m empty now, they may as well fill me with something.

‘Who killed us? Who brought down Heap House?’ they asked me.

‘Tell me,’ I said. ‘Wasn’t it you?’

‘Lungdon did,’ they said. ‘It was Lungdon that done it.”

“London, you mean?” I asked.

“No, no, we do call it Lungdon, we Iremongers. For we shall make it shift from London to Lungdon under our influence. It shall come all over Iremonger! Yes it shall, since it was them that done it, so now Lungdon shall be made to feel it. Now Lungdon shall suffocate on itself. Can’t kill off the Iremongers, can’t be done.’

‘Lucy,’ I whispered, ‘Lucy Pennant.’

‘She’s a dead one,’ said Uncle Aliver. ‘No discernable life pulse, on account of them.’

My family came visiting and prodded me in my misery, to set light to it. I didn’t eat much so they fed me with their hatred.

‘Well then, Clod, old Clod, shall we dead them?’ said Uncle Idwid, blind and full of grin. ‘Shall we dead them right back, my fellow lugs? How should you like that, my chick? Shall we that hear so, shall we hear them screaming? Shall we make them our instrument and have a nasty music come from them? I think we shall, oh I think we shall: they killed your Lucy.’

‘Quite murdered her,’ put in Uncle Timfy, not wishing to be outdone by his twin. This uncle’s birth object (whose name was Albert Powling) was a pig-nosed whistle, which he held threateningly in his small hand. But that whistle was not allowed to be sounded these days, not since we were all to keep ourselves as quiet as we may. Not since we’d gone into hiding, the House of Iremonger, all muted, waiting, waiting to move. All shoved into one heaving address.

‘They done for her,’ some relative echoed, chewing nonchalantly on his own greasy hair.

‘But you would have killed her yourselves,’ I said. ‘You should have, given half a chance!’

‘Maybe yes, maybe no, but they were the ones that did it. Not us.’

‘Did she scream?’ wondered Timfy.

‘Did they hurt her?’ put in Aliver.

‘Bet she screamed,’ concluded Timfy.

‘We’re entirely hinnocent of the crime,’ said Idwid, topping his twin. ‘No we never. You shan’t let them get away with it, shall you? To do such a thing. To one you were so partial to. Monstrous, is what it is, monstrous. Murder them right back, that’s what I say. You’ll do it, you’re the one to do it. You’re all black with fury, aren’t you, and so you should be.’

‘What are you going to do, cousin?’ said Moorcus, mocking. ‘Are you an Iremonger or not? Earn your nightshirt, why don’t ye?’

They are looking for us, I am told over and over, and if they find us they’ll snuff us out and we’ll never be lit again. But the longer they don’t find us, the longer they look in wrong rooms, and innocent houses, the stronger we grow, the more ire in our Iremonger there is. We are not allowed in London – I shall not call it by that other name – we are forbidden, we Iremonger people. We are illegals. They destroyed our home, so now, with no place, what else are we to do, but hide? We secrete ourselves upon quiet London shelves, so that all around us are only our own flesh and our bloodlikes. And all, though in strange surroundings, are horribly familiar company, my grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, servants, no one new but space. No new company. No one that isn’t blood. And there, close, breathing in and out our stale air, to prime ourselves and make cruel plans. In London. On London.

We help only ourselves, there are only ourselves to help. We move in one great fug of blood, we itch of Iremongers, a disease stuffed up in a single house, until we find, we hope, we hope, some somewhere where we may settle. Somewhere someday to call a home. But wherever could that be, and what would it even look like?

When I could I pulled back the curtains and looked out at the street before us, Connaught Place it was called. That’s when I saw her.

Someone else looking there.

Looking back at me.

A girl at the window across the way. The shock of it. There she was looking right at me. And then the great thing happened. She waved at me. The wonderful, terrible shock of it. Someone London. Waving at me.

I waved back!

I waved!

Oh the joy!

And then I closed the curtains and felt my heart sprinting. I looked out for her afterwards and when I could I waved again. The girl across the way. That little bit person of London.

But then, oh then, the last time as I smiled and saw her, I was discovered. Cousin Rippit was there fast as anything, he kept the voices about him so muffled. I didn’t hear him come in. He tugged the curtains closed. And a high long scream came out from deep in him, barely stopping for breath.

‘Rippitrippitrippit!’

He took hold of my hair and shook and shook me. He banged my head against the wall, like they used to do to idiot boys in the school room back at home, to smash some sense into us. It was expressly forbidden to communicate with any London person unless absolutely necessary, it was considered unbelievably dirty and also, and especially, most terribly dangerous to our security. So Rippit he banged and banged me. He scratched at me with his sharp fingernails.

Cousin Rippit, hunched and bunched in, squashed and horizontaled, flat crab-like Cousin Rippit, his eyes so wide apart, fish-face, in my face day and night. He couldn’t speak yet, not properly; so long and tough was his battle with his birth object, which as man had been Alexander Erkmann the Tailor, and as object was a rusted and twisted letter opener, concealed deep in a Rippit pocket. They had fought, ripping each other so, so much energy fighting length from width, stretching each other one in portrait, the other in landscape.

Always so close to me now, Cousin Rippit.

Day or night, I’d hear Rippit take my dear plug out, for he had been made keeper of James Henry Hayward, and croaked his ‘Rippit’ at it, he should never let me see my plug, never let me near it, he was the keeper of it now. He drew it out that morning after I was caught waving, he let my poor plug out the full length of its chain, and waved it before me, swinging it like a pendulum.

‘James Henry Hayward, James Henry Hayward.’

Oh my poor plug.

His own birth object was never revealed, but was kept always hidden away, lest it should pull itself out of his prison and be free once more.

Rippit, the croaker, the burper, the creaker, cracking his sound over me, into my thoughts and my loss, staring at me with his yellow eyes. My constant companion.

‘Rippit.’ My cousin, my frog cousin.

‘Rippit,’ in the night and in the day.

Rippit that caught me waving.

They painted over all the windows in my room with black paint, they nailed the windows closed and boarded them up. Keeping London from me.

They said they’d sent cousins Otta and Unry over to watch that girl, to see what she was about. Should I be found waving at her again, Unry and Otta would creep up upon her and stop her from meddling permanently. So I mustn’t wave again, it wasn’t safe to. Not for her.

I wonder if she ever thought of me afterwards, the girl across the way.

I was stuck in the room in my nightshirt, not allowed to go out, forbidden to look out, we must be quiet, we must keep still. But I cannot. Oh, Lucy, I cannot bear it.

This new home, home for a bit, a little bite of London, this room of mine. I shall ruin it, I think.

And so I did just that.

I only had to think it and it happened. How strong I had become, what things I could do! I’d so love to show Lucy, but I couldn’t. And so I ruined and ruined.

I blackened.

I sooted.

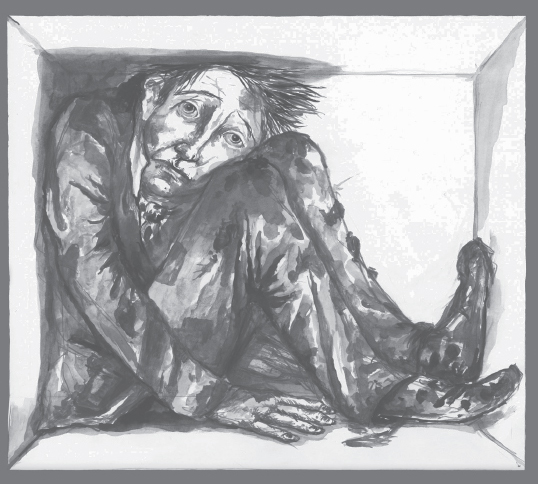

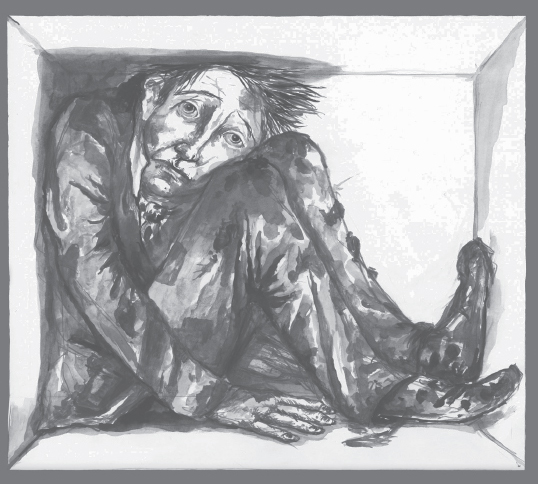

I breaked, bruised, buckled, bludgeoned, bloated and blasted. I hurt things now. I was so sad that I pulled my sadness out of me and onto all around me and I made all grow stale and rotten and unhappy. I spread my gloom, I sprinkled it. I felt it coming up inside me and belching out and then just by looking I saw the wallpaper start to weep and buckle, to grow strange blisters and hairs. It frightened me that I could do this. I watched as chairs grew awkward and unbalanced, their legs heaved long and thin and stretched to the thinness of needles and as they shifted they creaked and wept and longed not to be so strange, to go back to their former shape. But they couldn’t. I had been misshaped and so all about me must be misshapen too. Now was I made of hate.

I hated the wallpaper and it blistered and blackened.

I hated chairs until they stretched and shrieked.

I hated my bed and so its frame twisted and rusted, I hated the mattress and so it stained and bloated and belched out its guts of springs and feathers.

I hurt the things. And they let me do it, those things, they never called out, they never said a thing.

They do not speak to me.

Those new things never did.

All those about me, all those London pieces, were silent. They were only things, just little bits, small properties. They had no voices. They were not like the poor lost tortured bits of Foulsham that screamed and bellowed to me, that sung to me and lifted for me, and saved me, oh yes they did. I loved those things, every last whispering, howling one of them. I moved them and they moved me, and beneath them I heard them all and understood all their pain and distress, I knew them, I knew them. But these new things, these possessions of London, these expensive things all about me: why, they were dumb – every last one. It was only the birth objects of all my family about the house that spoke to me as we lived and breathed and hid in our new address. And yet I could feel them all, those bits and pieces, so much of this and of that, and I could have them move and bend and burn, I could shatter them and huft them with the slightest thought. I am Clod, the mover of objects, I am Clod, thing lifter, I am Clod and I may move, I do think, any thing. And break it.

Suddenly they were there again. I heard them outside my room in the night, talking about me.

‘It would seem to be his unhappiness that makes him so,’ Idwid was whispering outside my door. How his Geraldine Whitehead stammered beside him, as if those nose-hair clippers of his were afeard of me. And among the muffled noises I caught, barely, so timid:

‘James Henry Hayward.’

My own plug. And therefore Rippit was outside my door now too, whispering with the others, my own plug in his hands.

‘Yes, yes, the more miserable he is, the more the things dance for him,’ came the twin with the whistle.

‘Is he dangerous, do you think?’

I heard something saying, ‘Jack Pike,’ and knew at once it came from a cuspidor, and that Grandfather himself was without the door.

‘Oh, yes!’ said Idwid. ‘I would swear so.’

‘Can you control him?’ asked Grandfather.

‘Not I,’ said Idwid.

‘Rippit,’ said Rippit.

‘Good Rippit, see that you do.’

‘Rippit.’

‘I think, sir, I think, Umbitt Owner, Capital of Iremongers, great hope in our despair, father, father of us all, I think on the whole, just for now, while all is uncertain – just three nights, only three more nights and then we shall be there – I do think, in the meantime, you might leave Clod on his own and not come too much too close.’

‘For my sake?’ angered Umbitt.

‘No, no, of course not, however could that be?’ said Idwid. ‘I think you might find yourself wishing to punish him a little too much. And though I am certain he deserves such a walloping, it may be best, for the now, to leave him be and find himself.’

‘If you say so, Idwid. I’ve no love for the child.’

‘Indeed, sir, who could, who would … such a creature!’

‘We shall keep our separate ways, for now.’

‘I think it wisest. Rippit shall steer him right, shan’t you, Rippit?’

‘Rippit.’

‘Wait!’ cried Idwid. ‘I hear something.’

‘I too,’ said Umbitt. ‘It is the door! There’s someone there, at the front door downstairs. Hush all, be still!’

‘Rippit.’

‘Surely,’ whispered Timfy, ‘surely it’s locked.’

‘No, idiot brother of mine,’ said Idwid, ‘it must be unlocked. For Unry and Otta to come back in when they need.’

There was someone downstairs. Some non-Iremonger, someone from London. A very new person. I went to my bedroom door, but Rippit had locked it.

‘Let me out,’ I said.

‘Silence, Clod,’ came Grandfather. ‘Go back to bed.’

‘I’ve never seen a London person,’ I said, ‘not up close. I should very much like to.’

‘Lungdon, you must say Lungdon,’ said Timfy.

‘This is not the time, Clod,’ said Grandfather. ‘You will be silent.’

But I would not be silent. Be silent and miss this phenomenon amongst us? No. I commanded the objects all about my room to shift and dance. I had them flying all about me, scuffing the wallpaper, making such a din.

‘Rippit,’ said Grandfather, ‘silence that child at once.’

In response I made a porcelain potty shatter itself.

I heard a voice then, a young voice downstairs.

‘I think there are people here,’ the voice was calling. ‘Hello! Hello!’

‘Hello!’ I cried.

‘I have seen you,’ came the voice down below. ‘I’ve seen the fellow in the brass helmet. One of servants said she saw a dog. I’ve seen the young man upstairs in his nightshirt, I waved at him, he waved at me.’

The girl, it was the girl!

‘Rippit.’ He was inside the room then, Rippit was, closing the door behind him, shaking his head at me, coming closer.

‘Hello,’ I called. ‘Up here!’

‘Rippit.’

Rippit was at me. His squat, cold hand across my mouth. His sharp nails digging into my cheek.

I closed my eyes and, thinking hard, pulled a saucer from a table and, opening the door a moment, sent it downstairs, but that was not enough. So then I dragged every porcelain piece from about the house and made it rush over to her downstairs, to let her know that I was there, but not to hurt, never to hurt, to tumble near her, not to touch her, to play about her legs.

Though Rippit had hold of me, I heard the pieces falling.

But the girl was crying out now.

I think I had frightened her.

I never meant to frighten.

Rippit took hold of my hair and tugged hard at it, he kicked me in the shins with his sharp boots, he had his nails out to scratch and scratch. And then from one of his many pockets he pulled out an old rusted pudding spoon, and from another some small packet of stuff, which he dipped the spoon into until the spoon was heaped full of grey mixture. Grinding, he had some grinding to dull me. I should not take it, but he leapt and pounced, so agile for such a strange lump, and had a chair rush up to me – for he too could set the objects in movement by his thoughts – so that I found myself sat upon it, and then he was upon me again, the sharp fingers digging, those of one hand opening my mouth, those of the other pinching my nose shut.

‘I shan’t eat! Leave me be!’

‘Rippit.’

I spat at him, he dug his nails in deeper.

‘Rippit!’

He was so strong, strange Cousin Rippit, he had my mouth open, and the spoonful was shoved down me, I could not stop him. And very soon, very soon, very soon I was asleep. And then Grandfather I suppose must have taken over in his particular way.

In the morning, I crushed and cracked, I moved mercilessly from thing to thing, I could not stop myself, the doing of it was, I admit, such pleasure.

Clod, Clod, clever Clod.

Killer of things.

‘He’s at it again! Quick, call Idwid!’ wept my relatives.

‘He’s breaking things, he’s ruining his room,’ they cried.

‘Clod,’ Idwid called up the stairs but in strained whisper. ‘Clod, tidy your room.’

‘I shall not!’ I cried.

‘You must be quiet or we shall be discovered.’

In response I smashed a vase and did a jig in its pieces.

‘How ever did he come so wild?’

‘He never used to be.’

‘Such a shy one as was.’

‘So silent and obedient.’

‘Never one to raise his voice.’

‘Look at him now.’

‘So bold, so bold.’

‘I hate you all!’ I cried. ‘I hate every last drop of blood of you, I hate your skin and your hair, your vile organs, your yellow eyes and your selfish lives, your busy biles, your shrunken hearts, your lumpen livers, your fetid bloodways, your clogged drains, your grey stains in your swollen skulls. I loathe, loathe, loathe every last ounce of you all.’

‘Now, Clod man,’ said Uncle Aliver, our doctor, ‘you know you haven’t got that quite right.’

‘I’ll anatomise your anatomies!’

‘Listen to the child!’

‘Such a strong voice.’

‘For one who never shouted.’

‘Coming along most particular.’

‘Under Rippit’s special guidance.’

‘Ripening, I’d call it.’

‘He’s the one to do it.’

‘Ever has been.’

‘For good and all,’ I seethed at them and marvelled at my seething, ‘I’ll do nothing for you ever. You cannot make me!’

‘Thinks we’ll make him.’

‘No, we’ll never.’

‘Never even have to.’

‘He’ll do it, good and strong.’

‘He’s the man.’

‘Look at the very latest in Iremonger.’

‘Breaking the mould.’

‘Iremonger through and through and through.’

They made me so livid. ‘Doors!’ I cried. ‘Doors: make noise. All you house doors. Slam! Slam! Slam, I call you! Slam for all you’re worth, let them know my fury!’

The doors slammed all over the new house, slammed and crashed and kept on at it, because I, Clod, clot of black Iremonger blood, bleeding in heart and broken inside, in my little engine, my heart, my busted heart.

‘He’ll have us discovered!’

‘He’ll bring the constabulary upon us!’

‘Something must be done!’

‘To rein in the monster child!’

‘Before he pulls off the roof!’

‘And all Lungdon sees us inside!’

Then Rippit ran up and began to swing the chain of James Henry, to smash it against the wall, pelting it there, over and over.

‘James Henry Hayward! James Henry Hayward!’

‘Stop, Rippit!’ I cried. ‘You must not do that. It is against family rules.’

He put my plug in his mouth and bit down, and then did I stop the slamming of all the doors, and then did Rippit with a great ugly grin remove poor James Henry from his mouth, a line of spittle still attached to it stretched out a while before snapping. Then with his own power he carefully closed all the doors about us. And then the doors moved no more.

‘Rippit,’ said he, with finality.

I sat at breakfast in the stolen dining room in my dressing gown and slippers, the table so crowded with Iremonger mastication, the noise of them crunching and slurping, of so many tongues licking spoons, lips smacking, moist lips together and apart. Oh how epiglottises of ire wobble so, and beneath all the noises of their juices mixing, of the internal weather of their digestion, of their little gases being formed and creeping out into the world, to cause a small child somewhere to sneeze, an old woman to hiccup, a pregnant woman to gag.

I had me some fun, well why not? I do not regret my actions, not in the slightest. This is what I did.

I turned the food, I quite spoiled it. I dirtied and fouled it, I made it old and stale, I made it smell and bubble, I grew it some hairs and mould. Just by thinking it and staring hard upon it. And in response:

‘Good heavens, Pomular, look at the tucker!’

It belched of its own accord and spat maggots. There, I thought, eat that!

Aunt Pomular leant forward and stuck a finger in, prodded the greasy mass, scooped some out. She looked at it from different angles, a gollop landed upon the floor, and then, her head reaching ever closer to her loaded finger, she fed the remainder of it to herself.

‘Pomular!’

‘Don’t eat!’

‘It’s poison, I say.’

‘Most repelling.’

‘The terror of digestion.’

‘Oh God!’ said Pomular, gasping.

‘She’s suffocating!’

‘She’s suppurating.’

‘She’s spontaneously combusting!’

‘Oh God!’ cried Pomular once more.

‘What?’

‘What?’

‘What is it, Pomular?’

Pomular cleared her throat. ‘It’s really rather good.’

Other hands dipped in then, other swallows.

‘It is!’

‘It really is!’

‘Delish!’

‘Reminds me of home so.’

‘Come, come, Rosamud, not to be maudlin. Have another bowl.’

‘I will, I will, don’t mind if I do.’

‘I can’t help but remember the last time I ate seagull.’

‘Oh stop! You’ll have us all in tears!’

‘I’d kill for a good fat rat.’

‘Well honestly, Ugifer, who wouldn’t?’

‘I won’t be civilised,’ cried Rosamud.

‘No, Muddy, course you shan’t.’

‘I don’t like Lungdon, I cannot help it.’

‘It’s so clean.’

‘It doesn’t smell right.’

‘It’s bad for my health.’

‘I’m losing weight!’

‘But this, this at least, does taste good. A little like home. Thank you, Clod, so thoughtful.’

‘You’re a good fellow, Clod.’

Dear sweet Ormily, who would have married Tummis if the world had been better, there she was sipping at a glass filled with liquid the colour of mud. She smiled at me shyly.

‘I’m so glad to see you, Clod, up and about again. I am really,’ she said.

Dear sweet Ormily. I never minded her. We spoke the same language of loss.

‘Hullo Ormily,’ I said. ‘How I wish everything was different.’

But then Rosamud was in between us and, lifting up her brass doorhandle (Alice Higgs), she brought it down with a horrible thumping knock first upon my head and then, unforgivably, upon Ormily’s.

‘Young. Do. Not. Talk. At. Table,’ she said, and looked very pleased with herself for saying it.

‘Oh Rosamud!’ cried one of the aunts. ‘There you are quite yourself again. Good girl! Well done!’

‘Thank you, Ribotta, I am a mother now, and must help the young in any way I can.’

‘Binadit, I caution you, Cuffrinn, Binadit please to call him. He is … well he is rather large. They keep him in the cellar, in a metal box there. He is not really to see anyone, but I do pop down, when I can, I knock upon sides of his box and he bangs back at me.’

‘There’s love!’

‘There’s devotion!’

‘I do see my lost Milcrumb in his face, in his knocks even. It is a strain, you know, becoming a mother beyond the fortieth year.’

Oh Aunt Rosamud and her Binadit. Binadit in the basement, Binadit who knew Lucy, who had kissed Lucy once. I did not know whether to embrace the fellow for knowing her or to throw all things at him for kissing those lips, those lips gone quite cold now. I had not visited him, even were I to have been allowed, I could not bear to look upon that face. That big beast of a fellow. What should I do to such a creature who, I believe, in some way or another, Lucy had loved. He was down there in the cellar keeping her in his thoughts, having her play in his memories, little bits of Lucy that were his and not mine. I hated him then, him and his mother, that busy aunt with her doorhandle.

There were tears in Ormily’s eyes from Rosamud’s knock, she was very cowed and hurt, looking down into her watering can (Perdita Braithwaite) upon her lap. I could not stand it. Some switch went off in me, some firework lit, and looking at Rosamud blabbing on drove me in a fury, and thinking of her kissing son in a room beneath us and considering Rippit had broken the rules with my James Henry, shouldn’t I do likewise to these loathsome ladies, yes I was driven on and on. I silenced the trout, good and fast. Full of armoured thoughts I had poor Alice Higgs fly from her hands in an instant and sail through the thick black skin of a ruined custard where it floated miserable like the old HMS Temeraire going up the Thames before being broken up.

‘My doorhandle!’ she cried. ‘He moved it, he MOVED it!’

Silence.

‘MY DOORHANDLE!’ Rosamud screamed.

Then the others offered up their chorus.

‘It’s expressly against the rules to do such a thing!’

‘He’ll murder all civilisation!’

With a smile then I held my breath and shattered every glass in the room.

‘Disgraceful child! Call Idwid, call Ommaball, call Umbitt!’

Timfy had his whistle (Albert Powling) in his lips, and that was when I did it. Grinning widely at Ormily, I tugged at the whistle with my thoughts, I pulled hard on that chain of his.

‘My whistle!’ he shrieked. ‘My ever whistle! Oh Clod, I’ll drown you in tar water, I’ll boil you in rat fat. You! You spit, you gob of soap. Let go my whistle! I know you, I’ve yet to cut you for the burns you caused me on the dread night of the gathering in Heap House, when you sent a prehistoric fowl upon me.’

‘It was an ostrich!’ I cried. ‘It was Tummis’s beautiful ostrich, lost in the house.’

‘How it kicked and bit my person!’

‘I am glad, I am right glad!’

‘The one blessing,’ spat Timfy, ‘is that the dread beast fell out into the heaps and died there horribly, just like its dripping master!’

‘My Tummis!’ said Ormily, louder than I’d ever heard her.

Thinking hard then, oh wrapping my thoughts as hard as I may, I thought very small and round of the dried pea in the centre of Timfy’s pig-nose whistle, small and round, small and round, and I felt my thoughts about it, I felt my thoughts take hold of it and clench it in its thought-fists and I ground it and cracked it and made it into powder dust.

‘My whistle! My whistle, my whistle …’ stammered Uncle Timfy, like a small child with a broken toy, his voice very high now in his shock. ‘My whistle, my whistle, my whistle, my whistle, my whistle, my whistle, my whistle … won’t whistle!’ shrieked Timfy, the tears tumbling down Timfy cheeks.

Then Moorcus stood up, his chair crashing to the ground. ‘Right then, you maggot, now you’re for it!’

Taking up a candlestick, he came rushing for me and I with what quickness I could I plucked with my wishing his shining medal from his breast, it leapt in the air, he tried to catch it. It hovered around above our heads a moment. With a click of my fingers I set the ribbon alight and let it flame beyond Moorcus’s reach, until it had all burnt out and just the metal disk FOR VALOUR spun helplessly in the air.

‘You are the maggot, Moorcus!’ I cried.

There was the sound of clapping from behind. I thought at first it was one of the servants but it wasn’t. It was Rowland Collis, in the shadows amongst the serving crowd. Rowland Collis who had once been Moorcus’s toastrack birth object, but had turned back human again somehow, some magnificent somehow. Who could tell how he had done it? Rowland Collis had no idea and refused to return to toastrackness no matter how Moorcus begged him. Rowland Collis himself, Moorcus’s dirty secret.

‘Hi! Hi there, Rowland,’ I called. ‘Rowland Collis. However are you?’

‘Oh! Oh! Coming on I should say!’ cheered Rowland. ‘Enjoying the scenery! Partial to the drama!’

‘Toastrack!’ squealed Moorcus. ‘You will be silent!’

The unribboned medal still spun in the air; I let it drop now and it landed with a thunk in a tureen of puddled aspic.

‘That,’ I said, pointing at Rowland, ‘that there is Moorcus’s real birth object. There! Turned into the young man beside you!’

How they all gasped, my family. How Moorcus, his face so red with embarrassment.

‘No, no, it is not true. It isn’t!’

‘Oh yes!’ I bellowed. ‘That Rowland there was once a toastrack!’

And suddenly in all the glory of it, at the peak of my victory, I was shut up.

‘RIPPIT!’

I felt an itching on the nape of my neck, a sudden sharpness there, a tugging, a rising intense heat. My hair, my hair was alight! Rippit was setting my hair aflame – he had done this as a child back at home before he disappeared, it was his particular parlour trick. With the stench of my hair burning, I slapped the flames out, I grabbed a napkin, wetted it and applied it to my head. Else I’d have been burnt to a crisp.

I was sent to bed. Rippit took me by a fistful of my unburnt hair and hauled me upwards.

‘It isn’t, it isn’t true!’ insisted Moorcus. But all the family were backing away from him. Shocked and disgusted.

Granny came in to see me. Rippit sat at the window seat, chewing at his fingernails and licking his fingers and then applying the dampness to the parting of his greasy hair, to lay it flat upon his huge forehead, as was his wont.

Grandmother, shivering slightly, sat beside me in my broken room.

‘I like to travel, Clodius,’ she said. ‘I’ve quite the taste for it. I’ve been up to the attics and down to the cellars. I am out in the world. How large it is, the world.’

‘May I step out, Granny, may I? Into London?’

‘Into Lungdon, you mean. No, Clod, you might find yourself lost in a little instant, you might run away from all those that love you, we’ll keep you in pyjamas yet. Sit up, will you? I’ll have no Iremonger slouching before me. No, not you, Rippit, stay as you are. I know very well you are sitting as upright as you may. Clodius, Clodius you are an Iremonger! Whatever has befallen you to make you weep so, swallow it and let it shape you, and be the better for it. What has happened, Clod, has happened and you must chalk it down to experience. Now then, you can move things, you can, Clod, can’t you, child?’

‘I shall move out, I’ll move away, I’ll move far and far away.’

‘You, grandchild, if you’ve a mind to it, shall move mountains, whole cities even!’

‘I’ll do nothing for you, nothing good at least.’

‘Stuff and nonsense. You shall do as you’re told and be happy to do so.’

‘No. I won’t.’

‘I’ve never heard such cheek!’

‘You’d best get used to it for I shall not be turned.’

‘This is your grandmother talking!’

‘Yes and don’t I know it.’

‘I have been very excited! I have been moved, and it is never a good idea to move ancient monuments, architects never do advise it. The slightest thing may make them crumble. You, Clodius, you, Ayris’s only child, you shall not be the cause of my death, shall you?’

‘I, Granny?’

‘Be an Iremonger, Clod.’

‘Oh to hell with all Iremongers!’

‘You shame the memory of your mother.’

‘I spit on her memory, she means as nothing to me.’

Grandmother looked like all the blood had just fallen out of her. She trembled in her ancientness, she looked hurt and bent and I did not care, nor was I frightened of her any more, not of her disapproval, nor even of her Brussels sprout smell.

‘Monster child! There’s no love left in you!’

‘At last you understand!’ I said.

‘He is very ill, Rippit.’

‘Rippit,’ said Rippit.

‘Send for the pin.’

‘Rippit,’ said Rippit.

‘In times of distress, what a blessing is blood.’

‘You’ll bleed me?’ I asked.

‘Rippit!’ said Rippit. ‘Rippit!’

‘You’ve gone too far, Clod,’ said Granny. ‘Signalling to Lungdon people, breaking the furniture, hurting sacred Iremonger property, insulting your cousin and spilling secrets that were not yours to spill and now, on top of all, growing rude to your own grandmother, so, so you must take your medicine.’

‘What will you do to me?’

‘Why, Clod, as I said, we shall Pin you!’

‘RIPPIT! RIPPIT!’

‘Oh, murder me then, Granny, prick me with pins and pull all the blooding out of me, please do it! Hurry along!’

Granny cleared her throat, she called down the hallway, ‘Mrs Piggott!’

A thumping on the stairs and the housekeeper was within.

‘Yes, my lady?’

‘I want this floor of the house cleared of all family and servants.’

‘It shall cause a great deal of crowding elsewhere about the premises, my lady.’

‘What do I care of that?’

‘Nothing, my lady.’

‘Don’t get ideas, Piggott, you’re nothing but a servant.’

‘Yes, my lady.’

‘You make me ill.’

‘Yes, my lady, I am sorry for that.’

‘Don’t make me ill, Piggott, just do as I say.’

‘Right away, my lady.’

‘Only Rippit may remain.’

‘Yes, my lady.’

‘No disturbance under any circumstance.’

‘Yes, my lady.’

‘Nothing to upset such a delicate operation.’

‘Yes, my lady, I quite understand.’

‘Then bring up Miss Pinalippy, and be prompt about it.’