There was more smashing from inside, as if the nursery room was fighting with itself.

And from outside, police running, calling out.

I had never known such a thing to fight me like that nursery did, never felt such a weight pushing back at me. But I had to get in, get in to the roaring heart of it. All around me, up and down the corridor, the wallpaper was growing bubbles and falling off in strips, pictures on walls slammed to the floor; where my hands were upon the door two burnt imprints were growing. The door banged a little at last, it shuddered, I could feel the edges of it now, it wasn’t complete wall any longer, it was cracking, I was making my way in. Here I come, here I come. I cut into it then, cut hard like any knife, split my way through, and what a gushing there was, a bursting of things coming from the wound, a bleeding of furniture, of wallpaper, of floorboard splinters and then with a terrible scream as if a life sudden ended, a shocked yell, a general rumbling and then stillness. Dead now, dead again now. Door down, I stepped inside the body of a room in a house.

What a place it was, twisted and turned and bent and blackened, nothing there that hadn’t been shaken and shocked, what a carcass it was. This thing, once living, gone dead. Still warm though, but the warmth ebbing. What a thing is life and living. And behind the curtain, as if in hiding, a music stand whose name, the name it whispered, was Janey Cunliffe. She had been turned then, the girl that had waved at me, I was too late.

Only then, there, on the floor beneath the upturned bed, shoes, shoes with feet in them. The girl! Still! The bed I think had tried to lay upon her just as she had laid upon it night after night. Who could blame them all, they were only doing what she had done to them so often. I moved those things away, there she was, still breathing. A length of fire extinguisher hose around her throat.

‘I’m so sorry,’ I said. ‘So sorry, I had to do it. I am so sorry.’

I carefully pulled the fire extinguisher away.

‘You’re here now,’ she said, gasping.

‘I’m speaking to the room.’

‘The room!’

‘Did you set the room awake?’ I asked. ‘Were you so frightened of the fire extinguisher that you gave it the idea of life? Poor, poor things.’

‘It tried to strangle me.’

The unhappy girl was panting on the floor, and I looked all around at the lifeless room. Poor things, so still now, that only a moment before were roaring.

‘How proud they have become,’ I said, ‘how disobedient. I must say, all in all, it’s very something.’

‘They nearly killed me!’

‘They were looking for life.’

‘They would have taken mine!’ she said standing up, brushing herself down, pulling herself away from me. ‘A room coming to life? How could it? What’s happened to everyone? Where have they gone? My mother and father, all the servants?’ She was trying to make sense of it all. ‘They’re not here any more, and where they were strange things have been put in their places.’

‘Then they have turned. Alas.’

‘And who are you anyway? It all started …’

Then she seemed to comprehend something.

‘You are the dirty people, aren’t you?’

‘We’re Iremongers.’

‘Yes, that’s what I mean, the dirty people.’

‘Is that what you call us?’

‘I’d like to have my parents back.’

A police whistle sounding down the street, noises of boots: doors being smashed down.

‘It’s not safe here.’

‘The police!’ she said. ‘Come to save us.’

‘No, no. Those fools,’ I said, ‘shan’t last a moment, they’ll close their eyes and wake up a chamber pot. Don’t trust them, they haven’t the first idea: they think when you leave a room that a room stays still, that’s how much they know!’

‘I’m going to call them, I must do it!’

‘No, no, child, please think. Do you know of any policeman that can help people turned into objects?’

‘Well …’

‘And then – the next portion of my inquiry – have you come across people of late, strange people perhaps, who have done things, or can do things that have not been done before?’

‘I’m afraid to say I have.’

‘Then think, if those new strangers of yours, dirty though they may be, might be of more help than those you’ve trusted earlier. Because, well, the world’s turned rather new and strange, hasn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘there is no denying that.’

‘There we are then! Now listen, girl,’ I said, ‘there’s no one can control objects quite like I can. If you want to stay a girl you’d best come along with us.’

‘I’m not just some “girl”, you filthy person, I’m Eleanor Cranwell, full thirteen years old.’

‘Oh hullo, Eleanor. I am right glad to meet you. Clod Iremonger’s my calling.’

‘Clod?’

‘Clod.’

‘Clod? Do you even know what that means?’

‘Our names are like yours, only a little tilted, I know that.’

‘Clod means a lump, a bit of dirt or clay.’

‘Does it?’

‘It means, also, a fool, a dullard, an idiot.’

‘Does it? I didn’t know.’

‘Clod, he’s called,’ she said.

‘Lucy,’ mumbled Binadit, coming out into the hall, as Pinalippy quickly pushed Irene Tintype into the cupboard beneath the stairs.

‘What on earth is that?’ cried Eleanor, nearly screaming out again.

‘He’s one of us, he’s a fellow, name of Binadit,’ I said, introducing the great heap coming up the stairs. ‘One of our party, an Iremonger.’

‘He’s disgusting – there’s rubbish all over him.’

‘Get back, Binadit.’ And back he went. ‘Now listen, little Eleanor.’

‘I’m still thirteen!’

‘So you are, quite right. And an excellent age it is, one of those ages most ripe for bringing objects into life, I shouldn’t wonder. Now Eleanor, thirteen years old, is there somewhere where we might hide, somewhere not on this street, somewhere, some shelter? It must be indoors or otherwise Binadit here shall have all on top of him. He moves and all the dirt leaps on him, you see. He has so many skins of dust, don’t you, Bin? Can you help us, dirty though we are, to some place of sanctuary?’

‘Well, there’s Great Aunt Rowena’s, I suppose. She might take you in.’

‘An aunt of yours? Very good. She lives nearby?’

‘Through the back of the house, we can cut across that way. She’s very near, in Connaught Square. We can go now, if you like; I often visit my Great Aunt and am back and no one in the house has any inkling of it.’

‘Let us hurry then. She lives all alone, does she, Great Aunt Rowena? Such a funny name.’

‘Quite alone, yes. Just her and her servants, and her dolls.’

‘How many does that make?’

‘Three servants, twenty-two dolls last counting.’

‘An old woman, is she?’

‘Yes, she is rather.’

‘Poor eyesight?’

‘She wears glasses.’

‘Very good then; she’ll qualify, she’ll have to.’

‘I’ll say that you’ve all come for tea. We do often have tea parties, Great Aunt Rowena and I, and all her dolls.’

‘All right! Come along, all of us, whilst we still may.’

‘But what about the leather?’ wondered Pinalippy.

‘She must come along too,’ I said, seeing the poor flat-faced rubbish-girl’s false visage peering around the corner.

‘May I? May I!’

‘Yes! Yes!’ I said. ‘But keep her clear of Bin.’

‘I’m not going with any leather,’ said Pinalippy. ‘I’ve never heard of it. I am an Iremonger full-blood – the very thought of it!’

‘Then, Pinalippy,’ I said, ‘I’m much afraid you shall have to stay here, because Irene’s coming with us, she is our responsibility. I’m sorry for sending those others towards the police’s whistles now, that room has made me think differently.’

‘A leather, among Iremongers … as a shield, I suppose you mean. Very well then.’

‘As a person equal to us all. I think they must have some right to life after all, don’t you? Our people made them. I’m sorry about the other ones taken apart, but, well, I think it, I think she must have feelings too. Only thing is we’d better keep Binadit as far from Irene as possible, otherwise I fear, well, I fear she might come apart rather suddenly.’

‘Personally,’ said Pinalippy, ‘I think you’re an idiot, but there’s no time to argue. I’ll go on ahead then, the leather will come with me, if you’ll lead us, miss.’

‘Yes, yes, come along then.’

‘And Binadit and I shall be the last.’

And so we moved towards the back, as the police came to the door, and, finding it locked, began smashing it.

‘Slow, slow, Binadit, don’t wake the furniture. Slow, slow.’

Across the little garden at the back, all empty but for some paving, though Binadit caused scraps and clouds of dirt to spring up at each tread, and through the way until we came to Eleanor’s Great Aunt Rowena’s. More and more clouds of dust and dirt whirling all around Binadit. On we went, a single Londoner, Iremonger children and a leather girl, quietly into the night.

No one answered when Eleanor, our guide, pulled on the bell, but she had a key and let herself in. Binadit and I hung back, the wind picking up, or rather objects picking up and dancing gleefully about him, while I tried as hard as I may to keep the waves of swirling rubbish from breaking fiercely upon him. And after each wave came on, how the places behind him seemed cleaner, like they’d been scrubbed clear of a sudden.

Pinalippy pushed past Eleanor and banged inside.

‘This is my aunt’s house,’ Eleanor complained.

‘I’m sure it is, and I’m getting in it and quick too. Come on, in we go. Hullo, Aunty! We’re home!’

‘Please, please, let me do this,’ said Eleanor. ‘Hullo, Great Aunt Rowena, it’s me, it’s Eleanor, I’ve a few, well, friends with me, I do hope that’s all right. Anyone here? Hullo, I say. Pritchett? Knowles? Where on earth is everyone?’

There was no answer.

‘Come along, come in, Irene,’ guided Eleanor.

‘I’m Irene Tintype,’ she said.

‘I know you are,’ said Pinalippy. ‘Don’t lose your stuffing over it.’

‘I’m Irene Tintype,’ she said again, as if in further practice. ‘Irene like meany, not Irene like green. Irene Tintype.

‘Please, please,’ said Eleanor to Pinalippy, ‘you must understand that this is my aunt’s house.’

‘Very well and understood,’ said Pinalippy, ‘and that just over the road is the Queen’s police and I’d rather know the former than the latter: well then, where’s the aunt? Halloo!’

‘I’m sure she’ll come down in a moment, she’s rather hard of hearing.’

‘We’d best have Irene in a different room than Binadit, I suppose,’ said Pinalippy, ‘to avoid any huge noise. Is there somewhere she can go, and we can close the door behind her?’

‘The drawing room?’

‘Yes, wherever, as long as there’s a door.’

‘Here we are then, Irene.’

‘That’s the spirit and close the door quick!’ said Pinalippy, shutting it.

‘Whatever is all the fuss about?’

‘It’s Binadit and that one, they shouldn’t see each other.’

‘Why on earth not?’

‘It’s, well, how to say, it would be bad luck, and might go hard on the lea— on Irene.’

‘It sounds rather extraordinary! As if they were to be married tomorrow and seeing each other the night before would bring awful bad luck.’

‘Well, something like that,’ said Pinalippy. ‘All right, Clod, you may come along now.’

So we lumbered in and I had to rather push Binadit to get him through the door, but we’d managed before and did again.

‘I’ve put on,’ he said. And indeed, he’d grown several new skins since leaving the last house.

‘Yes, I’m afraid you have rather. I’ll try and get them from you, but they do stick so hard.’

‘They do look for me, I’m home to them.’

‘What a mess you’ve made!’ cried Eleanor, seeing Binadit and all the dirt about him.

‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’ he said.

‘It’s all right, Binadit.’

‘She’s angry at me!’

‘No she’s not.’

‘Yes, I am!’

‘Please, Eleanor, he can’t help it.’

‘He should be more careful.’

‘He can’t help it.’

‘Sorry, so sorry.’

‘He’ll ruin everything.’

‘It’s only rubbish that does it,’ I explained. ‘Things that have been thrown away. They all rather rush towards him. It’s because he was thrown away as a baby and the rubbish heaps saved him and now the rubbish bits are all his brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles: all his family, you see. And they do seek him out. They miss him terribly.’

‘You people are disgusting! I can’t even think why I’m bothering with you. You reek to high heaven. Put him in the bathroom upstairs – come on, up you come.’

‘A very good idea. In you go, dear Binadit, and we’ll close the door for now.’

‘And be careful in there,’ said Eleanor, ‘that is a roll-top slipper bath, the very latest from Bolding of Grosvenor. Great Aunt is extremely proud of it. Don’t go messing it up.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘No, no, nothing to be sorry for, Binadit,’ I said. ‘Just keep inside all right, just keep there, I’ll bring some food.’

‘Seagull? Rat?’

‘I’ll find something.’

‘You eat rat?’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said. ‘Don’t you?’

‘Oh God!’ she said and went further upstairs.

Poor girl, I thought, putting myself in her position for a moment, she scarcely knows what’s happening to her. It must all appear very upturned, we must seem rather odd fellows to her. And she is so, so clean. I’d never seen such a clean face before, I didn’t like to look too much upon it, if I was being honest. It seemed quite appallingly naked.

She was back down in a moment, tears in her eyes.

‘I can’t find my aunt, I couldn’t find my parents, where oh where has everyone gone? She wasn’t in her bed; this was though.’

She held, with some difficulty, a red-and-white striped wooden pillar, the type that barbers put outside their shops to advertise their business. Well then, here was the aunt. I could even hear her quietly muttering.

‘Rowena Philippa Beatrice Cranwell.’

‘Oh yes,’ I said, ‘here she is then.’

‘I’m going to speak plainly now,’ said Eleanor, her hands trembling. I thought she may cry any moment.

‘Please do,’ I said.

‘I’m very worried,’ she said. ‘I’m very worried and hurt and upset and I might scream any moment if I’m not persuaded otherwise.’

‘Please, Eleanor, to sit down.’ There was a bench along the landing.

‘I want you to be honest with me, I don’t want any lying.’

‘No, no, I’ll tell you.’

‘Where is my aunt?’

‘I’m very sorry, truly I am.’

‘Oh! Oh!’ she said, her hands trembling. ‘I’m holding her, am I?’

‘Yes, yes, I do believe you are. What was your aunt is now, is now this.’

‘Rowena Philippa Beatrice Cranwell.’

‘I can hear her,’ I said, ‘very faintly. She’s saying her name, she sounds peaceful enough.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘I hear things, Eleanor, I do hear them talking, and this wooden pole says “Rowena Philippa Beatrice Cranwell”.’

‘I never told you my aunt’s full name.’

‘No you didn’t; she did, this very pole here. She’s saying it again now.’

‘Rowena Philippa Beatrice Cranwell.’

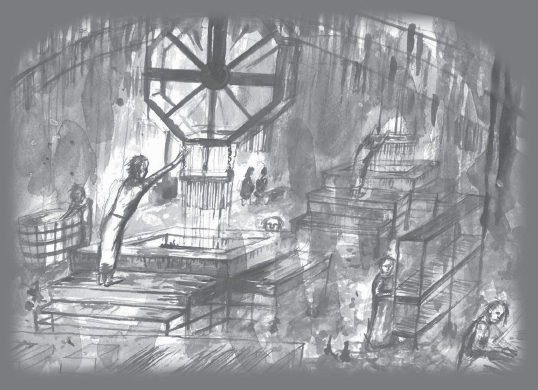

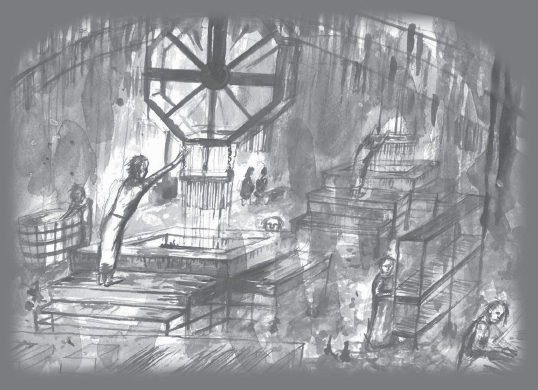

‘I saw it happen before, when you came to my street,’ Eleanor said. ‘The old man, he made the servant into a music stand. She was trying to help him, that was all. Why did he do that? Why did you ever come to our street?’

‘I am sorry. London destroyed our home, we had to go somewhere.’

‘Bring my aunt back. Bring her back right now.’

‘I cannot.’

‘Do it.’

‘I am unable to. I wish it were otherwise. But I think, I hope, if I can, to try to help you. To stop you turning. I shall try.’

The poor creature was so confused, so terrified.

‘Will she come back again?’

‘I, I don’t think so, I think this is what she is now.’

‘Poor Great Aunt Rowena!’

‘Yes, poor aunt. Let us not worry her though.’

‘Rowena Philippa Beatrice Cranwell? Rowena?’

‘It’s all right, Rowena, be still, don’t upset yourself.’

‘You mustn’t call her by that name! She’d be appallingly offended!’

‘What can I call her then?’

‘Miss Cranwell, of course!’

‘Dear Miss Cranwell,’ I said, ‘it is all right. We’re here. Eleanor’s here.’

‘Rowena Philippa Beatrice Cranwell.’

‘Will that happen to me?’ Eleanor asked, very quietly. ‘Will I turn?’

‘I will do everything to stop it. Keep by me, Eleanor, I don’t even know all I can do yet, just days ago I could hardly move a thing, and now I feel there’s very little I couldn’t shift. I shall try my guts out to keep you ever Eleanor.’

‘I’m watching you,’ said Pinalippy. She was on the stairs; I wondered how long she had been listening.

‘Oh hullo, Pinalippy, I’m trying to cheer Eleanor a little, you must understand this is all very new to her.’

‘Then she’d better catch up fast, hadn’t she?’

There was a snore then, coming from the bathroom. Binadit was asleep in the tub.

‘What on earth was that?’ cried Eleanor.

‘I do believe it’s Binadit,’ I said. ‘He’s sleeping. I do think that’s very sensible of him, perhaps we should all do likewise. It must be very late by now.’

‘The clock downstairs says it’s half past one in the morning.’

‘Please,’ said Eleanor, ‘will you sleep by me?’

‘I think that’s quite enough!’ put in Pinalippy. ‘He’s mine, we’re to be married.’

‘Why don’t we all find a spot in the same room,’ I suggested. ‘Why don’t we go and join Irene, she’s probably just as confused as you are, Eleanor.’

‘If she’s going then I’m coming along too,’ said Pinalippy.

‘By all means come, Penelope,’ said Eleanor, ‘and don’t scowl so.’

‘My name is Pinalippy! Please to call me so!’

‘Very well then … Pinalippy.’

‘And he’s my fiancé, just remember that!’

We went to the drawing room. I couldn’t see Irene at first, there was so much clutter. Indeed I do not think I had ever seen such a room for bits and pieces, for collections, for keepsakes, for mementoes, for gilt mirrors, for rocking horses, for globes, for trainsets, for wooden blocks, for elaborate birdcages with model birds inside them, for dolls – most of all for dolls, large and small, all seated here and there and all about, some even set around a green-topped table as if they were playing at cards.

‘I’ve never seen such an amassing before.’

‘My aunt is, was, a great collector.’

‘My grandmother had a great room of artefacts,’ I said, ‘but this is different. So many things here are from childhoods.’

‘She liked to play, you see; even though she was old, she still liked to play.’

‘Well and why shouldn’t she,’ I said.

‘What childishness,’ said Pinalippy. ‘What silliness.’

Irene Tintype was sitting just as still as all the other dolls; the only difference was the faint clouds of black smoke coming out of her mouth.

‘Hullo, Irene Tintype,’ I said, ‘how are you?’

‘Oh hullo!’ she said, sitting up, jerking back into life.

‘We’ve come to rest in here with you if we may?’

‘Come along, come along!’ she trilled.

‘How are you feeling, Irene?’

‘If you want to know, I’m feeling very angry.’

‘Are you, Irene, why is that?’

‘These people,’ she whispered to me, indicating the dolls, ‘they’re snobs!’

‘Oh I shouldn’t worry too much over them.’

‘No, you’re right I declare! They’re not worth the effort! I’ve introduced myself to them a hundred times and not one of them has once bothered to speak to me.’

‘Oh I see, Irene!’ I said. ‘The thing about these people …’

‘Such pretty dresses! I should like to have one of those!’

‘… the thing about them is, they’re dolls, Irene, they’re not real.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘They’re toys, they’re playthings, they’re imitation humans, they’re not real, they’re made to look like people but they’re just, well, stuff. That’s all.’

‘You mean they’re dead!’

‘They never were living, Irene.’

‘Why would anyone ever do that? Put bits together to look alive, to come so close to life but not to have it. What cruelty!’

‘I doubt very much their maker thought that, I think he must have thought they would be nice companions for a child, something to play with.’

‘To play with a dead thing!’ said Irene, disgusted.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘perhaps they were very well loved.’

‘What use is that to them?’

‘Not much, dear Irene, probably not much, but now I think we should get a little rest, and tomorrow we shall see how we fare.’

So we sat in armchairs or lay on the sofa and tried to sleep a little in that room thick with human shapes. Here I was with a girl of London, with a girl stitched from bits, with a girl who was supposed to marry me. Whatever has happened to the world to make such companions?

Pinalippy was the first to find sleep, and then Eleanor followed. Irene took the longest, indeed I’m not sure if she could ever sleep or if she only imitated it. She woke me up as I dozed, and she was in tears, muttering, over and over, ‘The poor things!’

Whatever shall the morrow bring?