7th February 1876

3–5 a.m.

John Smith Un-Iremonger came to us this morning with all his many instruments. I confess the man fills me with a certain dread and at the moment of his arriving a cold sweat came over me and I felt a panic in my chest. I know that I am not the only one to suffer so. I have seen Sergeant Metcalfe weeping behind his desk, huge burly man that Metcalfe is, I have known him these five years since, and never before was he wont to cry. It is the Smith that does it.

So very little is known about the Smith. He was used five years ago when certain bailiffs from London were discovered to be in Iremonger hands. On that occasion he stepped forward and, with his particular methods, had all the bailiffs disposed of. Brutally so if I am not mistaken. And then afterwards he disappeared again, as if he came from nowhere and went back there once more.

I have been told to let him do his work as he sees fit, never to question him. Indeed we shall leave him alone, readily. There’s something so unpleasant about his person. I cannot quite explain it. I am a very rational man, I have no true belief in God, save for how religion might help us to be better persons. But I think that – it suffers me so to write it and yet I must – I think that he is not quite natural. I think there is something very other about him.

I shall put down what I know in the knowledge that should anything happen to me and my men, this journal should stand as a record and testimony of true events as they unfold. I shall in my best way write as I see and not embellish but only speak baldly and express with all the exactitude I can muster. So then, understand I am a most sensible and rational man in my middle twenties, a young man, certainly, to have gained this position, but one, I may frankly account, who is good at his job, loyal to his service, strict but not unbending, a rule-follower and a good one at that. I do not drink, I have no fanciful persuasions, as I say, I cannot exactly believe in God and Christ, but I do most fervently believe in Queen and Country, which may perhaps be something of the same thing. I should lay down my life for the good of London, I do take risks on London’s behalf every day. But I am, beyond all else, a sensible man and a reliable one too.

Keep that in mind, who ever may read this, and reignite the knowledge as you read on, for I fear there shall be cause to remember it.

* * *

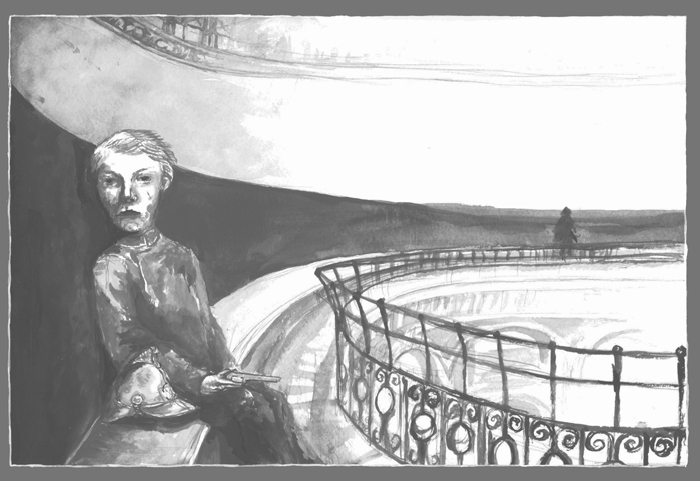

To begin in the best way let me try to describe the personage John Smith Un-Iremonger, if such a thing were even possible.

On the surface he is a most average man. There is nothing the least bit remarkable about him. He is very unassuming in his dress. In fact after he is gone it is almost hard to describe him with any exactitude.

His face, let me try to achieve that. Again there is little to distinguish here, a very average face, you might say. A blandly handsome face perhaps, with a neat moustache and mutton chops. A familiar face, I might even say that I have seen it before, and yet I cannot precisely recall it, but always when I am with the man I think I know him. He is very like someone, someone I know, only a bad version of him, a version, one might say, gone somehow wrong. And there I am again, I cannot say exactly where the wrongness comes from, only that he is wrong: Smith is very, very wrong. I have attempted to capture him in the latest police method, as you see above. It is the best I can do. The other thing about his face, the terrible thing: it does not ever seem to move when he talks.

How else might I exhibit him? His voice, his voice, is somehow muffled, it seems to come from deep within him, not to come from out of his mouth, rather from somewhere else in his body; it is a thin, whiny voice, wholly unattractive, like the noise fingernails might make scraping upon a blackboard. A most unnatural voice.

He is thickly dressed so that the least amount of skin is visible, indeed he never exposes himself apart from the face, only the face is ever spied, the rest – neck, hands, head-top – are all covered in layers of clothing with top hat or gloves or neckerchief.

He works alone, or with his own kind; we will not be permitted to run alongside him, he has other men at his disposal, but of these we see even less than the master. They are kept at a distance around the carts and cages that they use for their employ. I have not been close to one of these underlings.

And here I might mention some of the tools of his business: he has boathooks, and large butcher’s implements soldered to the end of long rods, he has pistols and rifles, there are strange traps and, I think, many disguises, he has odd whirring alarums too – sirens that he sounds, and steel whistles that are like police whistles only when they are blown upon no detectable noise can be heard, though they make the most vivid reactions in his small troop of assistants. As if those muffled men of his have similar hearing to that of canines or other animals. Again, how this discomforts my men.

He is very cruel, the Smith is, and very thorough. He finds the Iremongers where we could not have, and they are mostly extinguished before we come near them. He has only been on duty these few hours and already he has made much progress. The Smith has no qualms about shooting Iremongers in the street, or trapping them in such a way that afterwards there never is any breath to come out of them. He has taken this morning three full Iremongers. Cusper Iremonger, a former clerk in Bayleaf House, Pomular Iremonger, a middle-aged woman from Heap House, and last of all Foy Iremonger, a girl found limping through the streets of London heaving a great lead weight. Smith has discovered these individuals and he has killed them.

* * *

I do find myself wondering about the method of removal of these pestilential people, the tool being such an improper person himself; I do wonder if the cure is as repellent as the malady itself.

How can I say it clear? I have been struggling with it all morning, at last I seem to have come upon the answer, or one at least that satisfies me for the moment. So then, see below, my recent conclusion regarding John Smith Un-Iremonger:

I think that the Smith is a man who is without life.

I think that he is dead.

A dead person who is somehow moving among us. The skin of his face does not quite look like any other human skin; it appears hard to the touch (heavens, I do not think anything could induce me touch it).

7th February 1876

7 a.m. (the sun still not risen)

To add to our woes, various peers of the House of Lords have gone missing, and several Members of Parliament too. Posters are being printed. Lord Kilburn is missing and Lord Milfield disappeared early last night. The MPs for Southwark and Cambridge have been missing three days. There are now several thousand missing persons reported around the capital, but these latest are the first amongst the high ranks of the country.

8 a.m.

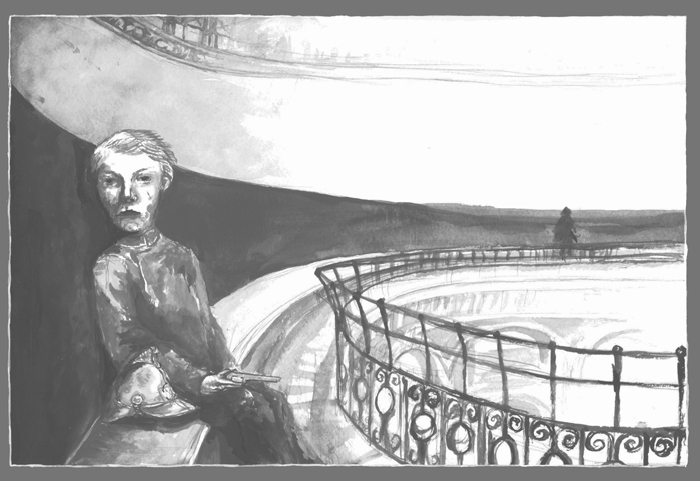

To the Mill Bank Penitentiary this morning at the Smith’s insistence. The pens are kept in the prison of Mill Bank, they are indeed most highly private and must remain so. In these pens we keep what few underlings of Foulsham we have managed to round up; some were caught in the rubble of Foulsham itself and kept extant for study, and others have been found trying to escape. They are pitiful children, for the most part. Some more were found just last night, escaping through the sewer lines. Some more are known to have broken free into London from the burning rubble town, perhaps as many as five. There is purported to be a leader of these trespassing children, a feral girl with wild red hair to match her ferocity. Judging by the impression of her on the Police bill poster now being distributed about the city, she is indeed a singular creature of vivid intensity and clearly a danger to the general public. No doubt she shall be quickly discovered and perhaps may lead to further information regarding the family in hiding. The redhead has a name, according to the new prisoners; she is called Lucy Pennant. Well then, Lucy Pennant, may you enjoy what last hours of freedom are left to you.

But to return to the Smith and our visit to the Mill Bank pens and to those of Foulsham gathered there. These are not, you understand, Iremongers of blood. Rather, these are the lesser people, the dirty poor of that place, who have somehow, through cunning or accident, survived the terrible torching of their miserable home. Here they are watched most thoroughly and from afar. They shall never be allowed to mix with our people of London but must always be kept at a distance, so that gates of iron separate this lesser species from the common Londoner.

We are awaiting orders to exterminate them – I am most grateful that it is not my division that shall carry out such a charge. For there is part of me that might consider them human.

No, for certain, I never do like going to the pens. I must wash myself very thoroughly afterwards, and indeed when I go home I shall have my Vera make me a scalding hot tub and bring with her what brushes she has to scrape hard upon my skin.

Some strangeness occurred in their pens when the Smith came to visit. He upset the prisoners a great deal, and for this I cannot blame them; it makes you think the poor creatures human, and almost similar to us.

They shook their cages mightily when the Smith appeared and did howl and weep and get about as far away from him as their limited confines would allow. His presence does agitate them terrifically. Just this morning I was witness, or part witness, to so unnatural an event, that I do think I must have become confused in my mind. But meet it is that I set it down, as honest as I may. And quickly too, for I cannot bear the writing of it.

There was an old man in a pen, huddled over and shivering, not well it is true, and Smith singled him out and went to him. At his orders he had the cage unbolted and the old man, shaking in a misery, was sat before him, but then – this most strange thing – the Smith in his screeching strange voice he says,

‘Bless you, bless you, my dear friend, do come to us, please do come along now.’

And he strokes the man, with such tenderness, he pats him so gently upon the head like the old man were just a child and he, the Smith, were the child’s mother. And the old man shaking so, takes a terrible big breath and he rattles rather inside, and then – I could not see him well, for the Smith’s back did mostly shield him from view – there was a very quick awful dying of the old man, a sudden tumbling of his corpus, an awful stillness came over him, and his pale skin lost all warmth to it so quickly, and was within the shortest of moments a lifeless grey. And – I know this sounds most unlikely, but please, I am trying to be as plain and honest as I may – and then the old man seemed no longer to be there at all, seemed somehow to have vanished quite out of life. In his place, upon the straw, was nothing but a pewter ewer, rather a nice one in fact. Where it had come from, and how it came to be there, I have no notion.

Then – oh, would that the writing of this were a way to pass on the knowledge and so be rid of it, rather than duplicating it as I feel I must – then, the Smith, as I see him from behind, takes one large breath, his whole body rises, and then, and then, then the ewer is no more there. Neither old man nor ewer, but only ever the old straw and nothing, nothing more besides.

John Smith Un-Iremonger rose from his knees, to his full height and asked – oh that voice – to be let out now. And so it was done, all were too affected to react otherwise. And now, it does seem to me, that the gentleman – must I call him so, no, no, no, I find I never can – that Smith is a fraction taller than he was before! Perhaps I do imagine this, but before he was of my height, or very near, but after the strange incident, he seems about an inch longer.

Then something strikes home to me, an idea, a notion, a horrible consideration, so ghastly a summation: that the old man has somehow been eaten.

That John Smith Un-Iremonger is somehow eating the prisoners.