In my dreams I heard them, those particular sounds, sounds of lost names. In my sleep, clear as anything.

‘James Henry Hayward.’

‘Ada Cruickshanks.’

My plug.

And Lucy’s matchbox.

Calling to me, like they were so near I could almost touch them, that I could almost hold them.

I woke up very suddenly. Pinalippy was right in front of me, her face very close to mine.

‘Sleep well?’ she asked.

‘What are you doing?’ I said. ‘Where ever are we?’

‘Lungdon, my heart, Lungdon. Only one day and one night between now and our reckoning on Westminster Bridge, and I must keep you safe until then.’

‘I had such a dream!’

‘I must wake you, Clod. It is very necessary that I do it. You see there are policemen in all four corners of the square. Miss Eleanor here’s been out already demanding news, and she’s been told to keep in, that there have been reports of disease spreading along the street and so now the street has been quarantined.’

‘Good morning, Clod,’ said Eleanor. ‘They’ve put up blocks at all exits to the square. We’re not to go out, we’re to stay put and wait until there’s new permission for us to move on again. Just like my great aunt and her servants, people on this very square, Clod, have changed too. It’s all blocked off, apparently, between Hyde Park and Regents Park. The army’s been called in too from Knightsbridge Barracks, to keep us in our places. What a strange, unhappy holiday this is.’

‘Let us think of it in a good way, if we can,’ put in Pinalippy. ‘Now we’re sealed off, no one can get to us; we’re being guarded here, it may be very useful. If we stay here unmolested we may bide our time until we need to go out again. Yes, it may be good news. We can get to know each other better, can’t we, Clod?’

‘We are to put strange new objects,’ said Eleanor, ‘inexplicable things, things we never knew before, on our front doorstep so that they may be taken away. They say it’s essential we do this, to avoid the sickness spreading. Do you think that will keep us well, doing that? Do you think it might?’

‘I cannot say precisely,’ I admitted. ‘It may, perhaps.’

‘Then I shall do it. I’ll gather up Great Aunt Rowena and Knowles and Pritchett, I’m going to wrap them in blankets to keep them warm. It seems so cruel, I think. I scarcely know what makes sense any more. I am glad you’re here, I will say that. I don’t know quite what I should have done all on my own. I suppose I must gather them up, mustn’t I?’

‘Well then you do it,’ said Pinalippy, sitting down. ‘I don’t know what’s what here, so I can’t really be of any help. Best if we Iremongers don’t peek out on the whole, and we may as well be comfortable whilst we’re still able. Yes, I like me a nice sofa.’

‘I’d like to go out,’ I said.

‘We wouldn’t want to lose you, Clod. Stay close, and stay warm. You may share this sofa with me.’

‘Oh Pinalippy!’ I said, remembering. ‘I had such a dream, such a dream as I’ve never heard before.’

‘Lucky you, I barely slept at all.’

‘I heard my plug as if he was very close, as if he was in this room.’

‘Did you?’ said Pinalippy, and looked quite put out by it, as if it shocked her somehow. ‘I shouldn’t worry over it very much,’ she said, though her voice wavered. ‘It doesn’t mean anything. Rippit has your plug, remember, and I’m sure he’ll look after it. Sometime, if I can, I’ll get it for you, just as soon as I have the chance. Don’t put any store by your dreaming, though, you’re just feeling the withdrawals, only natural after all. You’re yearning for it, well of course you are. I do miss my doily so. You’re doing very well, we both are, under trying circumstances.’ She concluded by tapping me on the head whilst keeping her body as far from me as possible, as if she feared rather to get close suddenly.

‘It wasn’t just my plug I heard.’

‘Oh yes? Something else?’ she asked. ‘My doily perhaps, finding its way into your dreams?’

‘I heard Lucy’s matchbox too, like as it was so, so close to me.’

‘Well!’ said Pinalippy. ‘I’m suddenly finding this sofa and this company most uncomfortable. I don’t call that very fair or nice, Clod, I really don’t! How could you! Just as we were getting on so well!’

‘What? What have I said?’

‘If you can’t tell then you’ll never know, will you!’ yelled Pinalippy and she ran from the room.

‘Oh dear,’ I said. ‘Whatever have I done now?’

‘Well I heard all that,’ said Eleanor, who’d come back in holding blankets, ‘and not to put my nose in where it’s not wanted, but it seems to me that you’ve insulted her.’

‘Really? Did I? I never meant to.’

‘Then you should think a little, Clod, shouldn’t you, before you speak.’

‘What did I say?’

‘I hardly mean to understand you people, but judging on what I know about how we of London behave: it’s considered ill form to talk of a former flame in front of your fiancée.’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘Ah.’

‘Yes, well then, now you have it. If you want me to give you some lessons on how to behave in society then I am ready and waiting. You do need some schooling, it seems.’

‘But I never wanted to marry her.’

‘I shouldn’t say that to her either.’

‘It was Grandmother’s idea.’

‘And clearly an idea that Pinalippy at least feels favourably towards.’

‘Ever since we were babies they said we must.’

‘Then you should have gotten used to the notion by now, shouldn’t you? Heaven knows there’s many a family in London that has such arrangements, many a good family.’

‘But then I met Lucy.’

‘I would think in these days when people collapse willy-nilly into things, when people all over the city are being lost and broken, are dying, Clod, dying, then it shouldn’t be too much, should it, to show a little kindness, a little affection amongst all the pain and horror. This is my Great Aunt’s house, Clod Iremonger, and if you can’t act more like a gentleman here and less like a dirty person I’d rather you left!’ And as she concluded she turned about very forcefully.

‘Where are you going?’ I asked.

‘I am going to comfort Miss Pinalippy, and then I am going to take the remains of my Great Aunt – whom I loved very much – outside with what’s left of her people and leave them on the doorstep, like common rubbish! That is what I am going to do!’

And so she was gone.

Barely awake five minutes and I seemed to have upset two women already. I’m not very good at this, I thought. It’s not my strong suit. We were all stuck with each other, that much was true in this fallen great aunt’s house, and I was sure that Eleanor was right, we should try as much as we could to get along.

All about the house through the day we scratched and itched like we had developed allergies to one another, and the mere sighting of one of our fellows was enough to bring us down deep into misery and headache. Irene Tintype alone was moving contentedly about the house, looking into every room and cupboard, and when she found a place locked, she glared through the keyhole, and so it was that she came to a particular room upstairs.

‘Oh!’ she cried. ‘There’s a man in the bathroom!’

‘Oh help!’ said Binadit.

Irene was at the keyhole.

‘I see you! I see him.’

‘Not to come in. Not to.’

‘Hullo there!’

‘Hullo.’

‘I’m Irene Tintype.’

‘Binadit am. Though “Benedict” she called me.’

‘Benedict?’

‘Then now there’s two of you called me that.’

‘Benedict!’

‘Hullo! Thank you!’

‘Benedict!’

‘Say again!’

‘Benedict!’

‘Do like it!’

‘Hullo, Benedict, whenever are you coming out?’

‘Not to.’

‘Must to keep in the bathroom.’

‘I see you! Through the keyhole.’

‘I see you!’

‘Hullo!’

‘Hullo!’

The two of them were laughing away.

‘When are you going to come out?’

‘Mustn’t, Clod says.’

‘Mr Clod! Mr Clod!’

‘Yes, Irene,’ I said, ‘what is it?’

‘The Benedict of the bathroom says that he mustn’t come out.’

‘And indeed, Irene, he must not.’

‘Oh dear, poor man in the bathroom. The poor Benedict.’

‘It is much better this way,’ I said.

‘Has he done something very wrong?’ she wondered.

‘No, no, it’s just that if he came out something very wrong might happen.’

‘Oh poor man in the bathroom, just the other side of this door. There’s no harm if I sit here and talk with him, is there?’

‘Not much, I suppose, but please do keep the door closed. Are you all right, Binadit?’

‘Benedict,’ Irene corrected.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘All right!’

‘Then please, Mr Clod, do please let us alone.’

‘Very well then,’ I said.

‘Hullo,’ said Irene through the keyhole. ‘I’m Irene Tintype. Not Irene like clean, but Irene like tweeny.’

‘Ree. Knee. Tin. Type.’

‘If you stay at the door!’

‘Well then, here I am.’

‘And come no closer.’

‘This close and no more, Benedict Bathtub.’

By mid-morning I still hadn’t seen Pinalippy again. Though I felt her hurt, as if it was a certain smell that could be sniffed all about the house, that the whiff of Pinalippy’s mood was somehow entering into our bodies making us that bit more restless.

‘And how do you feel, Eleanor?’ I asked when I found her in the sitting room.

‘I’m so turned outside in that I can’t exactly say. I keep looking at all the things about and wondering if that’s what I’ll be in a little moment. I can’t stop thinking of Mother and Father, of my poor Great Aunt.’

‘May I join you?’

‘Oh please, please do. I would dearly like some company other than poor Aunt’s dolls.’

‘Would you tell me something about London,’ I said, ‘to take the bad thoughts away?’

‘What do you want to know?’

‘Everything.’

‘Very well then.’ Eleanor cleared her throat and began to quote figures she had remembered from her studies: ‘The mean annual temperature is fifty-two degrees and the extremes eighty-one degrees and twenty degrees – the former generally occurring in August, the latter in January.’

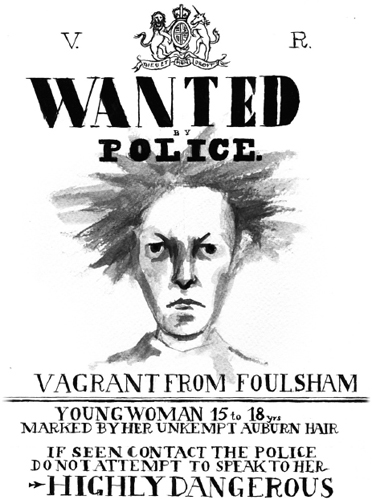

‘It was warmer in Foulsham,’ I said, ‘on account of the heaps.’

‘London,’ she continued, sitting very upright, speaking in the voice of a guidebook, ‘is situated very nearly exactly at the centre of the terrestrial hemisphere, which goes a long way, don’t you think, in explaining its commercial eminence?’

‘Erm … yes?’ I suggested.

‘The number of houses is upwards of 298,000. There are ten thousand acres of bricks and mortar. Of inhabitants, 2,336,060.’

‘All here? All in London!’

‘Yes, Clod. The Prime Minister is Benjamin Disraeli; the leader of the opposition Mr Gladstone. The Queen is …’

‘Victoria.’

‘Victoria, as you say. London has more than doubled in size in the last fifty years and grows steadily in all directions.’

‘It is alive then, the city, isn’t it.’

‘You may say that, I suppose. It has a great deal of everything, of rich and of destitute, of short and tall, fat and thin, and kind and cruel, of course. It is also,’ she said, breaking off the guidebook’s voice, sounding fully herself again, ‘my home.’

‘Here I am, sat beside a true Londoner.’

‘I am a school-aged girl and there are many thousands like me, each working their way towards becoming an adult.’

‘That’s a great deal of youth then, isn’t it?’

‘And future,’ she said, ‘and hope.’

‘Ah well, I am learning things!’

‘What are you going to do on Westminster Bridge, Clod?’ she asked of a sudden.

‘However did you know about that?’

‘Pinalippy mentioned it. She was talking to you but I was in the room.’

‘We’re to gather there tomorrow morning at eight of the clock.’

‘Who is we?’

‘My family, all my family, those of us that are left.’

‘And then what?’

‘I hardly know. It is Grandfather’s orders and he is the head of our family.’

‘Is it something terrible you plan to do, something monstrous?’

‘I do hope not. I think, above all else, it is a home that we seek, our own having been taken from us. We need a place in the world, a small portion of that which we may call our own.’

‘But why must it be tomorrow morning and no other morning, and why at Westminster Bridge?’

‘Truly, I do not know.’

‘But I do!’ said Eleanor, slapping her head. ‘I do! Tomorrow is the eighth!’

‘Yes, and what of that?’

‘I was going to go with Nanny! Oh! We had planned to set out early together so that we’d be able to see her as she passes along The Mall!’

‘See who, Eleanor, who?’

‘The Queen! The Queen! Tomorrow is the State Opening of Parliament!’

‘Oh,’ I said, still rather confused. ‘Oh. Then I suppose we shall be asking for a home.’

‘But you’ll never get inside Parliament, there’ll be police and soldiers everywhere. You can’t just walk in, you know.’

‘Well, Eleanor, it is not my plan, you see.’

‘You’re going to do something, aren’t you? What are you going to do? Why are you all meeting on the bridge?’

‘We have just been told to gather there.’

‘And will you go, will you?’

‘Yes, I think I must.’

‘You are a cruel people, I know you are. I saw you for a moment, don’t forget that, all of you in the house opposite ours, all crowded in the dark. You terrified me. You threw things at me. Things were moving in that house, everyday objects, as if they had life. You, Clod, you do not seem so cruel as the others, but how should I know? You may be the very devil himself.’

‘We do have a right to life, Eleanor; I think, as much as anyone.’

‘You mustn’t do anything terrible. Clod, you must promise me that.’

‘Why ever should I do anything terrible? Listen, honestly, Eleanor …’

‘Clod Iremonger, look at me.’

I looked at her.

‘Promise me, promise me that you’ll not harm anyone.’

‘Well, yes, I … I don’t really understand … but …’

‘Promise!’

‘Yes then, all right, I do promise. Of course.’

‘Clod, if you don’t mind,’ she said a little breathlessly, ‘I’d like to be left alone now. I wish to write my diary.’

‘Yes, of course. Sorry.’

‘You need not apologise, not to me at least.’

‘Should I go and find Pinalippy, do you think?’

‘Yes, I think it might clear the air rather. She is up on the roof.’

‘Well then, the roof it is.’

So slowly, cherishing each steady step before I reached the Pin, did I gradually ascend the fallen great aunt’s house.

Oh this business of human feeling, of keeping the engines, all the tubes of thoughts and emotions, all the cogs of love and like and hate, what a great effort it all was! How to make sense of how another person tocs and ticks, how to read their eyebrows and lips, how on earth to fathom, for example, the engine that is Pinalippy. There is no instruction manual to that. I’d always found that particular construction hugely complicated and wont to blow up in one’s face, as if there were no set rules to follow and that, well, she made it up as she went along. She was so many different weathers, was Pinalippy Lurliorna Iremonger.

The door of one of the maid’s rooms in the attic was closed; when I opened it I found there was rubbish all over the floor. I stepped in and shut the door quickly so that those bits shouldn’t find Binadit down below. A chair had been placed by a window. This was certainly where Pinalippy had got up in her brooding, and the rubbish, seizing a brief moment, had rushed in with the hope of finding Binadit. I followed her, pushing the window open and climbing through. Then I was out, out in the thick, dark, London air. There was rubbish all over the roof, skipping rubbish, streams of this and that trying to find the old heapmate. I crawled on through the cold wind.

She was further over than the mansard roof of the maid’s room, I could see her legs sticking out from behind a chimney stack. I began to crawl towards her on all fours. I hadn’t been up on a roof since the night I ran from a Gathering through the Forest of the roof of Heap House. The thought made me wobble a little, and yet still I must say that it was good to be out of that thick house, high up, on a small part of the top of London, of London Lid, of London skin. As I crawled closer I could hear talking.

Pinalippy was not alone.

The further up the roof I travelled the more I began to see the second person there. Two pairs of legs. Both female. I couldn’t hear their words exactly, not for all the noise of the wind up there and the dirt swirling about, hoping to get in.

‘I say, hallo,’ I called, because I’d quite made up my mind to talk to her.

The voices stopped.

I turned the corner. There was Pinalippy and there, next to her, she was coming into view, a curtain ring hanging from her ear: there on the roof of the Turned Great Aunt, sat my strange Cousin Otta with all her sharp teeth in her mouth, shivering in the cold. Her big head shifted in a terror at seeing me and she was very briefly another chimney stack, and then a grey fox, then a huge mastiff and then she was Otta once again, but the grimace still remained, very dog-like it was.

‘Clod!’ she barked.

‘Oh is it you, Clod,’ said Pinalippy, not looking in any way pleased to see me. ‘Forgive us if we don’t get up.’

‘Hallo,’ I said, ‘it’s Otta, isn’t it? You tried to trick me once, back at the House, you pretended you were one of Tummis’s animals, and your brother, Unry, was disguised as Tummis. Do you remember?’

‘Course I do. We did it to bring you in, didn’t we? To reel you in.’

‘That wasn’t very nice, was it?’

‘Nice! What a baby you are. Still stuck in the past are you?’

‘Still lost in your own little history, I gather from Pinalippy. Still in mourning.’

She changed very quickly into a box of matches – one with a tape across it marked SEALED FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE – and then she came back as Otta again, all this achieved in the merest seconds.

‘How clever you are, Cousin Otta,’ I said bitterly.

‘I’m teaching others to shift too, to grow into rats. How they come on, my many charges!’

‘Rats, indeed,’ I said.

‘She’s dead, Cousin Clod, your matchbox,’ Otta said, and she illustrated this by being very briefly a coffin, before returning to her human shape, ‘and the dead are growing in number all about us.’

‘Clod,’ said Pinalippy, ‘Cousin Otta has been so good to look for us, flying through the streets as a seagull, or in and out of houses as a rat and a beetle, but she has found us at last, and she came to report. There are less of us than before.’

‘We are being trapped, Cousin Clod,’ said Otta. ‘There have been some murders since we left Connaught Place. Iremongers, poor Iremongers, surrounded in these foreign streets, trapped and shot dead.’

‘Oh dear!’ I said. ‘Who has died, if I may ask?’

Otta illustrated the list of our dead. She was first of all an ink blotter.

‘Who’s that?’ I wondered.

‘Cusper Iremonger,’ said Pinalippy, ‘from Bayleaf House. A clerk.’

‘Poor Cusper,’ I said, ‘I never knew him.’

Then she was a letter knife.

‘Rippit! They’ve taken Rippit. That letter knife is Alexander Erkmann, Tailor of Foulsham. My plug!’

‘No, Clod, no. Look closer. This is in fact a butter knife that was Governor Churls Iremonger’s birth object, he that had been in charge of the great Heap Wall.’

‘Ah yes,’ I said, ‘him I’d heard of, but never met. Is it terribly wrong to wish Rippit a little harmed? Not dead perhaps, but he does frighten me so.’

‘I shouldn’t worry over that if I were you,’ said Otta. ‘It’s Pinalippy who should be the more worried.’

‘Pinalippy? Really? Why ever?’

‘Because he’s after her. He’s tracking her.’

‘Pinalippy? Otta, are you sure?’

‘I think he’s gone a little mad. I have seen him over Lungdon setting fire to things and to people. He has lost something of Umbitt’s and has gone searching for it, and now is most especially looking for Pinalippy.’

‘Well, Pinalippy, I shan’t let him do anything to you,’ I said.

‘Shan’t you now?’ she said, looking away from me.

‘There are others dead yet,’ said Otta.

She was a length of rope tied into a noose.

‘Oh, is that Uncle Pottrick’s?’

‘Yes,’ said Pinalippy, ‘Pottrick’s no more.’

‘Poor fellow, he never was one to love life, poor old man.’

Then Otta was a tortoiseshell shoehorn.

‘Oh no,’ I said, ‘I think I do know that, that’s Underbutler Ingus Briggs’s, isn’t it? Unless I’m much mistaken.’

‘You are not,’ said Pinalippy. ‘Shot dead in the street.’

‘Poor Briggs. He loved pincushions, you know; he showed me them once, was ever such a good fellow.’

‘Dead now, Clod, murdered.’

Then Otta was a lead weight with ‘10 lb’ marked on its side.

‘Oh!’ I gasped. ‘That’s Cousin Foy. They shouldn’t have killed poor Foy, she never was any harm to anyone, but was ever the gentlest of creatures.’

‘Dead now, Clod, quite dead.’

‘Poor dear Foy, that’s terrible. Please, please let that be an end on it.’

‘No, Clod, not yet.’

Next Otta was a footpump.

‘Not Cousin Pool!’ I cried.

‘Yes, Pool is gone too.’

‘He was my friend, you see, we sat together in Purgamentum Class, when we studied rubbish, back in the school room. And, oh no, please not, I wonder if, Otta, next you shall be …’

Otta was a hot-water bottle cover.

‘… oh dear. Oh Cousin Theeby! Theeby and Pool together! There never were such young people as loved each other so much.’

Otta was herself again. ‘I keep the tally, Clod. Our dead, you see, are mounting up.’

‘Oh Otta, I do see! Such cruelty, such horribleness, such murdering!’

‘That’s it, Clod, that’s it indeed. To your own family.’

‘And Moorcus? And his particular toastrack?’

‘They’ve not been seen, neither one of them.’

‘He tried to get us captured, did you know that?’

‘Though there is this,’ she said and was very quickly a wooden doorstop.

‘That was Officer Duvit’s.’

‘And beside it was …’

A folding pocket rule.

‘Officer Stunly’s. They were in on it too,’ I said. ‘I never wished them dead though. I’d never wish that, though I should indeed have words with Moorcus should I ever see him again.’

‘It was Rippit that killed Stunly and Duvit.’

‘Why on earth should he do that?’

‘For disobeying Umbitt, I shouldn’t wonder. He is such a wild one, Rippit, no controlling him. Umbitt shan’t keep him close and so he burns up here and there, and has gone quite vicious. He has lost something special that he was given to look after, and Umbitt Owner hates him for losing it, so now Rippit murders those he thinks have taken it. He’s broken off from the rest of us. When Umbitt berated him, he tried to set the old governor alight, he even burnt his coat tails until Umbitt, in his fury, banished him from all the family, spat him out. Oh yes, Rippit’s gone wild and lawless, gone very furious and cruel. And now, it seems, he looks for Pinalippy.’

‘Why, Pinalippy, whatever have you taken?’

‘Nothing,’ she said, deathly pale, ‘nothing at all.’

‘Those are the dead,’ said Otta. ‘No doubt there’ll be more yet.’

‘It’s not right,’ I said, ‘it’s not at all proper.’

‘Indeed, it is not,’ agreed Pinalippy. ‘It’s quite improper.’

‘A terrible wrong. An injustice!’

‘Something,’ I said, ‘something must be done about it!’

Both Pinalippy and Otta were looking at me with fierce intent eyes, and they said in precise union, ‘Yes!’

There was a silence then, just the wind blowing between us. I was shivering, shivering like I might break apart, but not from cold, from anger.

‘That’s my report,’ said Otta.

‘How horrid,’ I whispered.

‘Be an Iremonger,’ said Otta.

‘I am an Iremonger,’ I said.

‘Be an Iremonger while there are Iremongers left.’

‘I am an Iremonger!’

‘Prove it.’

Otta glared at me once more, shifted her bottom a little on the roof, raised her arms up, jumped and was in an instant a huge seagull, her curtain ring around a foot, heaving herself up into the air and back out into London.

‘It’s as if she blames me,’ I said. ‘I didn’t do it.’

‘No,’ said Pinalippy, ‘but perhaps you may stop it.’

‘Me?’

‘You.’

We sat a while up there on the roof, Pinalippy and I, in silence, shivering and steaming at the same time. How cruel it all was. I kept seeing poor Pool and Theeby, and Foy with her horrible weight. It felt so very near the end, sitting up there. Pinalippy was staring hard at me, I knew she was, and I didn’t dare look back at her. At last I muttered,

‘She is, you know, Cousin Otta I mean, in her way, quite incredible.’

‘Yes, Clod.’

‘A very talented personage all together.’

‘Yes, Clod, she is, for now, whilst she’s still living. We’re running out, Clod, we Iremongers.’

‘Oh, Pinalippy, I don’t know what you all want me to do! I’m just Clod, nothing more. I can move things and hear things, I can do that, but I am no great battle-knight, I am no thunder-god, I am merely … Clod.’

‘Hush, Clod!’ hissed Pinalippy. ‘There’s a policeman down below.’

There was indeed a policeman down there, he was wandering around the square, he had a lantern with him and he was gathering up the unfortunate objects that had been put out of doors by the sad, quarantined people within. We crawled close to the edge of the roof, the better to see him.

He had stooped down to gather at several houses already, some big objects, some small, and each glistened for a moment under the lantern so that we could vaguely make them out: a lacrosse stick, a decanter, a theodolite, a lectern, a pair of scales. Each time he picked an object up he looked around him briefly before carrying on. He’d been at three doors when I suddenly understood something.

‘See, Pinalippy, do you see?’ I whispered. ‘He picks up each object, waits a moment and then moves on.’

‘When he gets to the next door the object he’s picked up is no longer there, he’s not holding it.’

‘That’s right! But where can they have gone? He must have put them down.’

‘No, Pin, no.’

‘You called me Pin!’

‘They’ve not been put down at all. They’re nowhere to be seen.’

‘Then where’ve they gone?’

‘Look at him. What’s different about him?’

‘He looks just the same to me.’

‘No, look properly. See all the doors around the square are the same size – before he was a bit taller than the knocker, but now he’s longer than the door itself.’

‘And fatter.’

‘Yes, and fatter.’

‘But how can that be?’

‘He’s feeding on them,’ I said.

‘Then?’

‘Yes!’

‘Then …’

‘Then he’s a Gathering!’

‘A Gathering here in London!’ gasped Pinalippy. ‘I’ve got to tell them, I must send word to the others,’ said Pinalippy. ‘They’ll need to know.’

‘There may be many of them.’

‘To think what harm one single Gathering did to Heap House. And it is them, these Gatherings, that are coming for Iremongers, they must be the ones who have been shooting us! I must warn them. Grandfather pulled that Gathering apart.’

‘How about Otta? She can tell them.’

‘But she won’t be back until morning. I know where Umbitt Owner is, she told me, I’m going to send word. Besides which, I think I need to see Umbitt, I have something I must … tell him. If I can do this quickly then all will be well, I must just first get to Umbitt, he’ll protect me. As soon as this fellow has finished his feeding I’m going.’

‘I’ll come along too.’

‘No you shan’t, we’ll need you tomorrow morning on the bridge.’

‘Why, Pinalippy, what on earth is it I’m supposed to do on Westminster Bridge?’

‘You’ll think of something.’

‘But what?’

‘Think of Pool and Theeby, think of Pottrick and Foy, think of Briggs even and Timfy too, then maybe you’ll itch up a thought worth thinking. We have to stop them or we’ll all be dead, Clod, every last one of us.’

‘I must earn my trousers, I do see that now.’

‘That’s it. That’s a start.’

The policeman was done. He’d left the square.

‘I’m going, Clod.’

‘Must you go?’

‘Kiss me, Clod.’

I kissed her upon the cheek. Coming close to her I felt suddenly so complete, like I was all of myself again. That was so peculiar, such a feeling of togetherness I hadn’t felt since I’d had James Henry with me. How odd it was that kissing Pinalippy made me feel like that. Quite the shock.

‘Bye, Pin. Promise you’ll be back.’

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘Take good care.’

‘Shall try, I do assure ye.’

‘Keep clear of any flames, they might be Rippit, he does love them so.’

‘Bye, my Clodman, think of me a little,’ she said, and then her head came close to me, closer and closer, that head of Pinalippy, and she kissed me full on the lips.

‘Oh,’ I said, when she had withdrawn.

‘Well, then, I must be off.’

‘I’ll sit up here to watch you go.’

I sat there, my fingers on my lips, feeling so hot, feeling heat rising all around me. I must be ill, I thought, or it must be Pinalippy. But it wasn’t either of those – it was flames, nearby.