From Clod Iremonger

Clod. I must be very Clod this morning. The veriest Clod.

Bang. Bang. Bang.

I am hiding in ratform beneath a bench in the House of Lords, Grandfather has ordered me here. The door of the House of Commons is opened and now all the MPs do flood through the Commons Lobby across the Central Lobby getting closer and getting louder, all those top hats, to see them go, as if all the chimneys of Lungdon are on the move. Into the Peers’ Corridor and then into the Peers’ Lobby, louder and louder, and at last into the Lords’ Chamber. What a mass of them, all the members of Parliament, how they do throng and clot the room, and in the lead is the Prime Minister and the Head of the Opposition, but they cannot all fit in, there are too many of them, and all talking loudly amongst themselves.

Now there is a sudden squealing of rats, of my fellows under benches around me, followed by a sudden rushing of people all in black, who divide the MPs, squeezing out those who cannot well fit in and pushing them rudely back down the Peers’ lobby, and now the doors to the Lords’ Chamber are slammed, and now those people in their black suits roll a large marble fireplace before the door, it is Grandmother’s fireplace, it is tugged from its castors and let fall with a heavy thud before the door, and so now it is firmly shut. And so all are crowded in and can not get out. In an instant those runners in black are gone again, sunken rat-like and squeezed through holes.

‘What is the meaning of this?’ someone cries. How I do hear him from my hiding place.

‘What?’

‘What?’

‘What?’ comes back from some of the Lords and MPs, for they are leathers posted here by Grandfather in all his cleverness. Cries of,

‘Help! Help ho! Treason!’

And now a clack, clack, clack. And Aunt Ifful is there standing before the House of Lords.

‘Who are you, woman, what are you doing here?’ calls some gentleman, perhaps it is the Prime Minister.

‘I come to dim the lights,’ says my Aunt Ifful.

And she opes her mouth and lets some of her night out, all to the general horror of the people, such frail humanity, in the chamber.

‘There then, that is better,’ says Aunt Ifful. ‘Your Majesty, my Lords, members of Parliament, visitors in the Royal Gallery, please meet my family.’

And that is the signal for us all to come in, and so we, pinched and hairy, long-tailed and sniffing, rush then in a great tumbling through all the holes that lead into the Lords’ Chamber, or, like me, from under a bench. How many of us then, over a hundred I think, some of us have not been so lucky, some have been trampled underfoot by the Yeomen of the Guard as we waited in our furry clusters, our hearts moving so fast.

We must be an extraordinary sight, all us rats appearing here on the carpet, crawling around all that ermine, making a general panic. But now comes the greater moment, for we have all amassed to the noise of their screaming in the centre of the Chamber and now from our ratform do we grow human again. How strange to stretch and shift so, quite like the feeling I had when Grandfather spun me into a sovereign. I don’t like to do it, the feeling is wretched, something like vomiting, only a hundred times the worse.

‘Rats!’ the Lords and MPs scream.

‘Rats!’

‘Get them off me!’

‘What in the name of heaven!’

‘Call the guards! Why do they not come!’

‘Help! Help, I say!’

So we grow and we put away our tails and our whiskers and are soon enough got up like ordinary everyday men and women. We surround the MPs and force them forward in a knot towards the Queen’s throne. What a sight we are, all amassed beside the gentry. What a family!

‘Not rats … people. People!’

‘They were rats, just now!’

‘What magic is this?’

‘Who are you?’

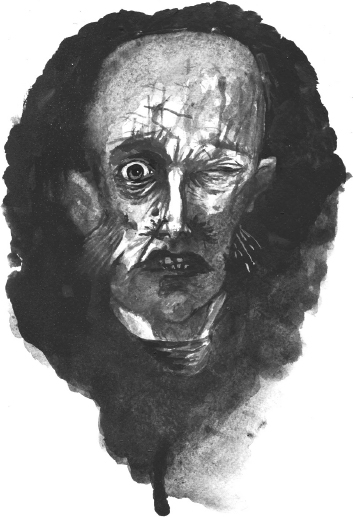

‘SILENCE!’ It is Idwid that calls out. ‘THERE WILL BE SILENCE! ORDURE! Well sir, Umbitt Owner, please, please, they are quiet now.’

‘Who are we, you ask?’ says Grandfather standing tall, all birth objects stuck about him, his pockets brimming, never did he look so grim and unbending, ‘We are a family, grown small in number, come to have words with you. Our name, Queen, is lost in fire and cruelty, but it may yet be heard whispering among any accumulation of debris. We were, once upon a time, the guardians of your filth. Since we have lost that title we have been forced to hide in dark cellars, forced to put away the sun, forced to limp and lick our wounds, we are … how may we be properly described? We are the bad smell caught in the wind, we are the strange tapping between the walls, we are the cup that fell down and broke on its own accord, we are all the lost keys, we are the floorboards that creak though no one is upon them, we are the shadows in your dreams, we are the bad feeling that can’t be shook, here we are, we alone, great Iremongers of darkest dirt.’

Great panic in the house, calls for help, for arms.

‘Iremonger!’

‘Iremongers!’

‘I was in the belief,’ says the Queen, ‘that there were no more of these people remaining.’

‘Ordure! ORDURE!’ cries Idwid.

‘Eleanor Cranwell,’ says the candleholder in my hand. As if she is trying to tell me something, as if she is trying to talk to me.

‘Well then, revise your beliefs,’ says my own grandfather to the Queen and all Parliament, ‘and breathe us in while you may.’

I step forward then, pushing my way through the crowding of uncles and aunts and cousins.

‘Excuse me, Grandfather,’ I say, ‘I need to speak.’ I do.

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

‘Clod, be silent,’ Grandfather replies. ‘There is no time.’

‘I shall speak I think,’ I say. ‘I will be heard.’

‘Clod, stand down!’

‘Your Majesty, for certainly you were never my Majesty, for you mean little enough to me. I am Clodius Iremonger –’

‘Who should be silent,’ says Grandfather.

‘And I am an Iremonger of some talent and force. I must blow my own trumpet, you see, for I wish you to understand, and must be quick about my talking.’

‘Clod!’

‘I do hear things talking, I do comprehend the disease, I know which people have turned into what things. Even now, in this room, there are so many names sounding in my ears. That was the start of it, do you follow? When I was a child, a babe even, I had this particular hearing. And now, you see, that I am older, I can move any object by thinking it; I have set whole houses alive. Well it is a terrible thing, I’ve grown very powerful and strong. And, Your Majesty, Lords, MPs, proper people, whosoe’er you may be, I want you to understand we are such a people, a people who are very clever: we may hear things and move things and command things, we may shift from rat to person, we may bring forth the night. Yes! But, and yet, there’s ever less of us, you see. It seems you have been shooting us.’

All the great men make a great play of straining to hear, to make sense of my speech, and in pausing they take this opportunity to scowl at me and no doubt find me young and foolish, and some try to speak but I will not let them and go on again.

‘Yes you have! It seems you have been murdering us. We had a home. Out there, a home which you destroyed. You murdered Foulsham. How could you, how could you ever do such a thing? Was it to keep you safe in your warm rooms, to sit by the fire with your particular possessions hard about you? Well if that’s the reason, then you have failed, have you not? For we are here, and the disease is spread thick about you. Let me tell you now, I came here to murder you.’

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

There is a little silence after I’d let that one sink in, but it is not followed by the cries of help and shock that I had anticipated – the result is rather a few smiles and then several deep laughs.

‘Child,’ says a man, and I believe this man to be the Prime Minister, Mr Disraeli, ‘you fail to terrify. It would be best for you and your people behind you to give yourselves up and cease this rash and foolish behaviour – no good shall ever come from it. The longer you persist the greater shall be the consequences. Put away your music-hall theatrics and leave this hallowed chamber, for you and your kin are not invited here.’

‘You speak to me as if I were just a child.’

‘Child, being school-age, I must.’

‘Hear, hear!’ comes a rotund peer.

‘I am Clod!’ I say.

And there is more laughter at that.

‘I am Clod!’ I cry once more.

Yet more laughter, from all around.

‘So you keep saying,’ one Lord calls out.

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

‘You should listen to me, you know. You should not mock me. I am grown quite strong, you see.’

‘Parliament will not be held to account by some child!’ a Lord bellows.

‘It will!’ I cry. ‘Oh I do swear it will. I may pull all Lungdon into the Thames if I have the will to do it.’

Much laughter at this.

‘London,’ some bellow, ‘the place is called London, didn’t you know?’

‘Do it, Clod,’ says Umbitt my Grandfather. ‘Do it now!’

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

‘Yes, Eleanor, I do hear you.’

‘Do it, Clod, move all!’ cries Grandfather. ‘Bring it all down!’

‘There have been so many deaths,’ I say, giving them a last chance at life, ‘can we now, do we now, allow a little living? This is but our demand and our need: a home. We want a home. We require one. A home, I say, please, a home.’

‘We do not negotiate with criminals,’ says Disraeli, growing impatient.

‘But you, you are the criminals!’ I cry.

‘No home, no home!’ say some MPs.

‘Do it, Clod, do it now,’ says Grandfather, come close beside me.

‘Yes, Grandfather, yes I shall.’

I close my eyes, I move forward just a little, and the whole building begins to shake.

Then the Lords, the MPs all about, stop their mocking and commence to gasp and to call out. And to think I’d merely moved the house one single step. Now they are listening.

‘We do not negotiate with criminals,’ says Grandfather, ‘Now, Clod.’

With my eyes closed I raise my hands, I call in my thinking so many objects all about, I call them up into the air, lift them high into the air all around Parliament, and then very swiftly I bring my hands down.

And then! What follows!

It is as if Parliament is being gunned and cannoned and pelted and pocked and thumped and shot and pitted all over, as if now it is a body with black holes, riddled with a plague.

What noises, what screams inside as all that outside smashes against it in a dreadful wave; windows shatter, pieces come flying through.

I open my eyes. Everyone in the chamber is so frightened, they are in such a terror. I did that, I caused them such distress, people are weeping, some are bleeding. What a thing! What a business, as dear, lost Lucy would have said. Another barrage like that and I do believe I shall kill people, many people.

‘Again, Clod, do it again,’ says Grandfather. ‘Good, my boy.’

I close my eyes, I lift up my hands.

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

The candleholder in my pocket is calling out to me. I made her a promise once, before she betrayed me, never to hurt anyone, and now I am about to bring forth another crashing wave, to hurt these who hurt us, these men who signed the paper that brought about the terrible burning of Foulsham, these people who killed Lucy. Now, now shall I be fully revenged.

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

Now I shall.

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

Now, now … and yet … I stall … and yet I cannot. I cannot do it. I have come so far, but now in the last moment, I am not able. I do not want them dead, I just want a home. I cannot do it, I lack the heart.

Clod the fool, Clod the idiot. Coward Clod.

I open my eyes and slowly lower my hands. Nothing stirs, all look at me. I cannot do it.

‘Now, Clod,’ says Grandfather.

But I cannot.

And so Grandfather raises his bloody fingers and with a wave of motion a great many of the MPs fall, collapsing into objects. There are mop handles and dustpan brushes, there are two ink bottles and one set of dentures, some mirrors, undergarments.

‘Where have they gone?’ one MP shrieks. ‘The MPs for Sussex and Cumberland, for Kent and Gloucestershire, just beside me now, have quite vanished!’

‘I demand you bring them back at once!’ One ruddy-faced MP steps forward and with a flick of Grandfather’s bloody fingers is reduced to a wing nut.

‘We have indeed not come to negotiate,’ Grandfather says.

And as he speaks, Ifful beside him spews more night into the Chamber.

‘Then why, why for heavens’ sake have you come?’ It is Mr Gladstone who asks this, as I stand hopeless with my family, unable to go on.

‘To hurt. To do harm,’ says Grandmother.

‘Eleanor Cranwell!’

A general movement from the populace all about.

‘Some people, please to understand,’ says Grandfather, ‘make better objects than people.’

He walks around the Chamber and, flicking his bloodied fingers about, he turns a person here, a person there, at random, to show his cruelty. Twenty MPs and ten Lords fall down. He has their attention very well then, oh they are attending excellently well at last. He means to murder them all; what a family we are, what monsters. What have I done?

Another person falls, and another. A wooden-handled drill, a bathing hat.

‘No, Grandfather,’ I say, ‘do not do it. It is enough already.’

Noises from without: people are trying to smash the doors down.

‘Save the Queen!’

‘Save the Queen!’

‘I shall save the Queen … until last,’ Grandfather says. ‘Here shall be great hurting! Now Clod, come forward, wake yourself up, you may do your worst, pelt this house down, pull it into the very river! Earn your trousers!’

‘Eleanor Cranwell!’

‘Stop him!’ cries a Lord.

‘I shall, I’m the one to do it,’ that is Moorcus calling from somewhere in the ranks and he comes forward now with his shooter waving in front of him.

‘No, Moorcus,’ I say to my cousin, ‘do not do it.’

‘No Moorcus, do not,’ says Grandfather.

‘A gun!’ someone calls. ‘He has a gun!’

‘Gun!’

‘Gun!’

‘There’s a gun in the house!’

‘Yes, there is,’ says Moorcus and straight away he fires it.

It isn’t a very loud crack. I barely hear it. I see a brief flame and then all goes slow for a little moment, and then, of a sudden, I’m knocked over. I’m on the ground. I see myself spilling out.

From Moorcus Iremonger, murderer

Yes! Yes! To see him fall! To see the bullet leap through the air and burrow and bite into Clod like it was born to do it. And down he goes and down and down! And that ridiculous top hat of his topples after.

‘You’re dead! You’re dead! I’m not!’ I sing.

Like he’d lost the idea of life and living. What a puppet!

And Grandfather, he cries out, ‘Fool! Cursed child! Murderer of Iremongers!’

‘No, Grandfather,’ I said, ‘he wasn’t one of us, not really.’

‘You, Moorcus,’ bellowed Grandfather, ‘you have killed us all!’

There he lies now. Clod’s on the floor where he belongs and he swims in his own red river, and does flail in it, oh yes he’s pouring out. And my pistol is hot, as hot as a heart because it spat just now and done it proper!

I! I! I am the Clod killer!

Crack!

What was that? Small sound after all those others. Like a stick being snapped. Whatever was it …? It sounded like. Didn’t it? Gunshot? Such a strange feeling, I look down at my chest … I … bleed … bleeding … I look up, what … Toastrack! Toastrack up there on the balcony with my own other gun. I mustn’t die, no, no, please not to. I am the hero of my life!

Ah me!

From Rowland Cullis, formerly a toastrack, now a murderer

Toastrack I was. I ever hated your company, you splendid little toff, all those do thises and do thats, well then, have at that now, why don’t you, how does it feel? I was very lucky, such a fuss over two ladies being thrown out because of the Queen’s say-so, and all the boys with lanterns causing such a fuss, I slipped in then, suddenly no one was watching, up I went, up the stairs.

Yes I’ve a shooter, Moorcus, and I’ve been longing to plug you with it and I meant to do it publicly so that all may see that I did it.

‘How are you then?’ I call. ‘How do you feel? However do you do, Moorcus? My name is Rowland Cullis.’

He does not say a word.

‘Shut up,’ crows the blind one, the Governor Idwid, his head looking the wrong way. ‘Shut up!’

‘That the Queen there, is it?’ I call. ‘Hallo, Majesty, here I am at the Royal Gallery. With my shooter. My name is Rowland Cullis, I was a toastrack before now. I’m sorry about Clod, he was all right, he was. Are you still with us, Clod? You’re deathly pale. You too, Moorcus, you’re greyer; how you do leak – watch the carpet!’

Bang, bang, the people outside trying to get in and others trying to get out, and I am grabbed now, there’s people in the gallery waking up from all the shock, they have a hold of me and pulling me down, my hands behind my back, my gun on the floor.

I am guilty, guilty of the charge. I shot Moorcus, I did it.

From the voice of a Gathering

We are John Smith Un-Iremonger. Came long ago from Foulsham, the very first of us, a tiny cog, once a man but shifted horribly by cruel Umbitt, thrown over the wall into London. That was the start of it, so many years ago; how we’ve collected and grown since then. We are all of us here bits and pieces put into clothes, our hearts are spinning things, we are here in the Chamber, we are waiting, we are waiting. The old man has so many things, all his pieces, all birth objects, all that was once people and we are hungry for them, they are what we want to eat, to eat them all and then shall there be no more Iremongers, all shall fall like us but first must eat, must eat. We. We were Emma Jenkins, Sybil Booth, Lester Ritts, Mary Ann Stark, Giles Bickleswaite, Theobald Villiers, Elsie Bullard, Leona Rice, Lloyd Walters, Elliot Murney, Dorothea Towndell, Matthew Stokes, so many and many are our names now lost, now no more but stuff, here we are. We’re sharp and blunt and heavy and light, we are soft and hard. We’re here now inside and we’re coming in, more and more of us from outside this chamber, smashing upon the door. More gathering about to join us. Stuff dropping from the old man, he cannot hold them all any longer, he is ill, the things no longer cling to him. What’s that? That’s a lady’s shoe size ten, name of Cecily Grant, very good then.

One of us dressed as a peer leans forward from his bench – looks such a noble Lord – stretches out his hands and takes up the shoe, then looking left and right he quickly puts it in his mouth, swallows down the piping inside. Grows a bit.

Bang! Bang! How they cry to come in! The many more of us, police never understood us, let us grow so big, let us, did the Police Inspector Harbin.

There’s another Gathering, a larger Gathering just outside, it shall break down the door! How it bangs upon it!

From the Iremonger matriarch, Ommaball of great blood and age

‘Stand proud, stand firm, Umbitt. Do not waver. Turn them, turn them all! And let us be rats again and gone!’

How frail Umbitt is, how frail but still he must do it. Those people! I hate them so, trample on them all, change them every last one and let us dance on their pieces let us break them into crumbs, let us lose and destroy them. But quick, we must be quick about it. We have sealed the chamber and trapped ourselves in. And there lies Clod, in his blood, our lost hope, and the traitor Moorcus grey with death.

What’s that about my feet? Rats! Rats! Iremongers changed to rats!

‘Cowards! Cowards! This is Ommaball Oliff that calls you – be human once more. Stand proud! Be Iremongers!’

But they are not, the traitors, they are rats.

Step on them! I shall step on them!

‘Piggott!’

‘Yes, my lady.’

‘Piggott, step on those rats. Step on them.’

‘They are Iremongers, my lady.’

‘They are not worth my spit. Step on them I say, dance your heavy boots upon them, crush and crush!’

‘Yes, my lady.’

Good, good, she’ll do it, Piggott will, she has spirit.

‘My lady, look! Look behind you!’

But … what?

‘Piggott! Piggott! Piggott’s gone rat on me too! Come back Piggott, come back, I shall crush you now.’

But look, now, look, look at the people on the benches, they’re moving, they’re shifting, they’re sitting closer and closer together and then they are melding into one, yes! They are coming into one, how can that be? Faces fall off! Not faces, masks, masks on the floor! All the clothings are pulled off and it stands tall. All those spinning, shifting things inside.

‘A Gathering!’ I scream. ‘A Gathering is within! Umbitt, Umbitt!’

But Umbitt stands there, his hands dripping, more and more things falling from him. As one Lord stands up from his bench and another and another and, dropping his wig, dissolves into the main Gathering, which grows, it grows and grows!

I stand back, I cannot go any further, there’s nowhere further to go, rats about me, I do not blame them now. Gathering coming on, closer and closer.

‘Do something, Clod, do something, earn your trousers!’

I am backed into my own marble fireplace, I feel it, I feel it … moving. My own birth object! Being moved from the other side!

‘Clod, Clod,’ I cry, ‘do something, this is your granny here, demanding it!’

‘Clod! Help!’ Idwid is calling in the darkness, ‘I hear nothing, the Gathering is too loud! My ears are bleeding! Iffull, love!’

‘Idwid, love! I come with extra night!’ cries the Iremonger of many lungs. ‘Get up, Clod! Get up and be useful! Oh, look out, Ommaball Oliff! It falls!’

Such fuss they make, but what about me?

‘Help me!’ I cry. ‘Help me, oh my children!’

It moves, it is falling now.

‘Oh! My own birth object!’

It comes!

‘Um—!’

From Inspector Harbin, coming in

The whole Parliament building suffers such terrible damage, Saint Stephen’s tower is terribly broken, the clock quite shattered. Into this ruined palace have we rushed in desperate haste. I have made allies with a giant made of things, a mass, a colossus, which has broken the oaken door of the Lords’ Chamber, and in we come at last. Some of my men besides me, just behind the giant. And there are boys about me again, boys all over, I could not stop them. They came rushing in when the Smith with all his faces of Albert burst through into Parliament. They will not go back, these boys with their lights, they come for their Queen I do think. They have lit our path. That’s it, lads, you’re patriots one and all, shine your lights, shine on, and let us make sense of this terrible darkness, put the darkness out, I say. I wave at the boys, my pistol in my hand, to let them on, so that all may see.

‘Light! Light ho! Light, make some sense of the world!’

It’s then that I see her, then, as more light comes in. The girl with the flaming hair. The one we’ve been seeking, the dangerous one, smashed a policeman, there! Right there! Right before me, the very girl! She must be stopped. You must stop her, Harbin, I tell myself, even if you have to kill her.

From Lucy Pennant, coming in

A Gathering, a Gathering larger than any Gathering that I ever saw. Larger yet than the one that nearly pulled down Heap House. But … I don’t know how or why, or what it means, this Gathering seems to be helping, helping the police. I hate these police, these murderers of a little girl called Molly Porter, they shall answer for that one day, I do swear it, but not now, now is not the time, now is Clod’s time and so we do run with a Gathering. It has broken down the doors, what a great crash as they slam to the ground and now the Gathering pours in afterwards, it laps and bursts against the walls of the chamber within. And me and the link boys, we follow after, with our lights, come to see what’s what, as all those broken bits of Gathering do gather themselves up again, do try to form one big, heaving mass.

Where? Where is he?

‘Clod. Clod? CLOD!’

I can’t see him, I can barely see anything. And all the noise is the rushing and clattering of the Gathering as it swerves around and tries to come together, smashing into object and person alike.

‘Some light, light now!’ a policeman calls.

The boys are about, I just see them small pools of white, but then as soon as they’re lit they’re out again in a moment and I can just hear a strange hissing sound, like gas coming out of a pipe, extinguishing the lights. Something else is in here.

‘Clod, Clod, where are you?’

The hissing sound, the blackness spreading everywhere, I feel it on my face, I feel it as I breathe in, I feel it coming down inside me.

‘Yes, yes, Ifful love, blot them out.’ A man’s voice in the dark – that’s Idwid Iremonger, I know him.

There are other people around, there are many others in all the darkness, mostly they are keeping quiet I think because of the Gathering hammering around them, they are seeking some shelter, they are trying to hide. I hear people crying, calling out. There’s a woman’s voice in the distance, I hear it muttering the same sentence over and over, ‘Calm as a clam, calm as a clam.’

The Gathering has stopped now, it’s all gone very quiet. Nobody moves. There is something very close to me, something huge, clicking and creaking. It is the Gathering. The new Gathering, as tall as the chamber itself, it is right beside me. I hear the noises of it, small instruments sounding inside it, wind through tubes, it’s clicking to itself, the hollow tin rumblings of its many stomachs. It is feeling about with its hands made of many different fingers of metal, porcelain, rubber, glass, wood, cloth, stone, it’s feeling about on the floor, it’s searching, it’s trying to find something.

It’s feeding.

I hear it, it’s looking for food. It’s eating, it’s stuffing things into its many mouths, this great beast of objects, it’s picking things from the floor.

From the voice of the Gathering

So big are we! Such size! Come together! More, more yet! Here they are and here and here, all these bits fallen all over the floor, all these that were Members of Parliament and Peers of the Realm, how good they taste, but most of all the best morsels are still with the old man. We want to eat those Iremonger pieces, eat them all, every last one and then there’ll be no Iremonger left to bully and to break us. How they caught us and trapped us and kept us prisoner, no more ever again, we’ll eat every last Iremonger thing and then they shall all tumble, one and all. Here, here’s a thing on the floor, something else the old man has dropped, he can’t keep hold of things now, how he litters! What a thing is this? Want it, do we want it? It’s a something called Geraldine Whitehead, nose-hair pincers. What a thing, we shall eat it!

From Idwid Iremonger

‘Geraldine? Geraldine!’ I, Idwid, cry, my ears, a cram of voices, but I heard her, my Geraldine calling out. No! No! I had a Geraldine!

‘Idwid, my darling lugs! Why do you cry so?’

‘Oh Ifful, Ifful, it has eaten my Geraldine, oh, oh!’

‘Oh Idwid, my heart! Come to me, come to me.’

‘I’ll rat to you, Ifful, I’ll turn rat and run to you, keep me, keep me safe!’

I turn and slip and unfold, and shrink skeletons until I am rat once more, and now must to my Ifful. But I cannot see, and all the noise echoes inside my hairy ears. Where to go, where to go?

From the Gathering

There’s a rat running and running in circles, between our hundred feet … indeed what feet we have – great boots, iron clods, wooden feet, women’s shoes, children’s, old people’s slippers, high-top button boots, Oxfords, Cromwells, sandals, work slippers of Berlin wool, brogues, ankle boots, beaded, punch-worked, flat-sole shoes, kid leather, straight-soled, square-nosed, quarter-tipped, all footwear from so many here and there, shifting in the darkness, and between all our many feet runs a blind rat in and out of us, we shall stamp on it, we shall stamp!

Stamp!

Stamp!

From Lucy

The whole Chamber is reverberating, shaking, smashing, as the Gathering tries to squash something under its many feet, and still I cannot see Clod, where are the link boys and their light? Each time a flame is lit up the same hissing comes again and more darkness descends.

Stamp!

Stamp!

Please, please stop, it shall break through the floor in a moment.

Stamp!

Squeal!

The stamping has stopped now.

From Ifful Iremonger, widow

‘Idwid, love, Idwid? IDWID!’

So dark, it will always be dark now. I shall darken the world and keep it dark, I’ll put out all lights, I shall end every lamp in this city, I shall swallow up all matchsticks, candlesticks, tallows, flints. There’ll never come any more warmth; now and forever all is cold and loveless.

They put out my sun when Idwid died. And now I shall hiss and hiss.

Lungdon shall never see light again.

What?

What’s that?

Now some other boy with his little lantern dripping weak heat, no, no, it’s something else, something bigger, can’t see to put it down quite, though I vomit and vomit and out comes black, still some more lighting does come.

What is that which defies me, what is that?

Is it?

Can it be?

Rippit?

Fire? Fire!

I can’t put it out!

I spit at it and it spits back.

I’m light! My hair! I AM SO BRIGHT!

From the Gathering

Dead rat. Dead blind rat. Now what, what now?

Where’s the old man? Where is he, there’s good pickings with him.

Feel him, feel for him, touch him and rip him with all your thousand, thousand scrapers. Old man, old man, we come!

Umbitt, running out

Here I hide, Umbitt, that once was great, here now in my sad moment, my empire forgot, my family dispersed and ruined, my own wife, loving Ommaball, crushed to death by her own marble mantelpiece. How big the Gathering is, so strong, so strong. And I am old and ill, the engine of my body trembles now and shudders. This, can even this be my end?

I was Iremonger.

I was.

It comes, the Great Gathering, it smashes in its search, it lifts benches, it feels underneath, it whirls and screeches, the noise, the hunting noise it makes, how it cuts into me. It is looking for me, I know it is. What have I left? Only me now, only me and my own cuspidor given to me by my own loving father.

It’s stopped now, the beast has, it’s silent, not a clink from it, not the slightest creak, I must too keep very still, not move, not an inch, it’s ready to pounce, I do feel it.

‘Calm as a clam, calm as a clam.’

That voice again, a woman in distress. Not just any woman, the Queen herself. That’s it, that’s it, do go to her.

‘Clam.’

‘Clam.’

My leathers, dear leathers, moving forward.

‘Clam!’

‘Clam?’

‘CLAM!’

It’s found them, the Gathering, it’s killing the leathers, ripping them open, the stench of the rubbish comes out from their leather bodies, but it does not eat them, it merely rips open, ruins and moves on.

‘Clod? Clod?’ A young voice, female.

That’s the horrible red-haired child, the scum from Foulsham, I made her into a clay button once before and I shall do it readily again. I had her thrown out into the heaps by that same dead child that lies there, shot by his own birth object. Oh this is the end of days. But that child I hate, the red-haired one; without her the Iremongers should have stayed true, without her Clod should have smashed all; it is her doing. Now I think, now I shall clay button her once more, I do think I shall. It should be my pleasure, but how, how to do it without giving my hiding away?

Smoke. Smoke!

From Inspector Harbin

Smoke everywhere now! There’s fire, there’s fire!

‘Fire!’ I cry. ‘Fire! Great fire in the House!’

From Tommy Cronin, Mill Bank Link Boy, fleeing Parliament

Church candles don’t burn bright enough, but that’s no matter, there’s enough fire all around now to make everything seen. However shall we get out of this? However did it start? I seen policemen and soldiers suddenly call out, tug off their helmets, their hair all in flames, running out in a panic, and the walls suddenly whoosh with fire and we must retreat, we must fall back and even as we run we’re being set light to, our hair does fire up like any match! We go back, all fall back whilst we can!

From ill-faced Georgie, Mill Bank Link Boy, outside Parliament

I seen such a strangeness, such a queer fellow. Who is that man, whoever is he? He’s so squat and flat, like something very heavy has sat on him. Whatever is he doing? Why, he’s dancing, he’s running around and around, this strange man on Speaker’s Green, dancing around a little dance to himself and as he dances he whips himself up into a frenzy and fire, somehow, fire comes out of windows!

Anyone comes close to him suddenly bursts into flame!

I think he means to burn all London down and destroy all things, all people, and only be ashes left.

From Rippit, dancing upon Speaker’s Green

RIPPIT! RIPPIT! RIPPIT!

From Lucy

There’s some light now, coming through thick smoke, light from outside, flames through the window, the whole Parliament surrounded by the flaming, and heat coming on, pressing on. But in the dancing light how the Great Gathering does pull itself up, does seem to gasp, to stretch away from the floor to shoot upwards in many strands and columns to try to flee from the fire, it is hammering now, in so many thick knots of fists, hammering upon the roof, trying to burst through.

But there is new light, light all around, there – and there he is! Clod lying on the floor and blood all about him.

‘Clod? Clod! Clod!’

From Clod on the floor

Clod, here I am, Clod. So many voices, so many names, they do crush down on me so, I cannot make sense of them all, just a roaring, a great roaring. I am going now, falling out, oh what an ending … there shall be no more Iremongers now after all, never and never, no home, we’re breathing out now, slow and slower.

Moorcus, it would have to have been Moorcus all along.

‘Eleanor Cranwell.’

Bye then, Eleanor, dropped on the ground. Thank you. I close my eyes and fall asleep.

Someone’s shaking me. Someone’s tugging at me.

Leave off, shan’t you, I’m slipping away.

Still shaking me, grabbing at me.

Go away, I’m dead.

Yet still I am bothered, not left alone to die, to drift off in Aunt Ifful’s dirty inkness. Leave alone. Just leave alone.

But whoever it is, keeps heaving at me, pulling me back.

Go away, go away, I’m sleeping.

Still I am shook so.

Leave off, shall you, I’m dead.

But the great bully won’t go, but keeps shaking and prodding at me, and I seem to hear some distant words above the roaring, someone’s calling my name. Let them, let them, this knocking shall not be answered. The door is closed, and won’t be opened again. Give in, shan’t you, give a tired chap his little peace. Is it so much to ask?

There now, good. Whoever it is has stopped.

There now, at last, my own corner of quiet.

I am alone. There now, there, old Clod, off you go.

It doesn’t hurt.

‘Clod, Clod you bloody dare!’ I shake him and shake him and he won’t wake. Wake, wake Clod, oh Clod you bloody fool. I can’t have it, I can’t have it. ‘Clod! Damn you! Breathe! Can’t you?’

He is so still. I can see no movement, none at all.

‘Oh Clod! Please, please.’

Not a thing.

‘Oh Clod, what am I to do after all?’ There’s a Gathering as great as a mountain, a heap on its own, taking up full half a room, and a Queen in the corner with tears down her face and men all around her in suits and red dresses, all sweating and dishevelled. That’s about the picture of it. There’s some few policemen left, panic all over them, stopped and useless in their terror. There’s your miserable grandfather hiding behind the benches, watching us, looking up at the thing and then down to us. There are rats all about, running and screeching, and dirt and bits in piles here and there, and here am I, your own bloody Lucy, all hemmed in. That’s about the size of it. Well then, what’s to be done? And you lying there on the floor, all dead on me.

I take his plug out, I lie it on his chest.

And as I do it that great mound above and to the sides shifts a bit and stops its moving.

‘Clod,’ I say. ‘Oh Clod, Clod, I think that thing of things is looking at me. I cannot see its face but there are so many bits of it pointed now in my direction. I don’t like it, Clod. Clod, however do you stop a Gathering? Oh Clod, Clod, it’s slowly falling, it’s shifting closer, it’s beginning to avalanche towards us. Clod! CLOD!’

And that’s when I hit him. Hit him hard across the face just like I did when first I ever met the dolt, just like I did up in that attic room in Foulsham.

‘Clod bloody Clod BLOODY CLOD!’

From Clod

Hit me. Hard across the face. Such a jolt. Pulling me back, how that hurt hurtling back, the sudden wind in me, weather all about, and the pump my little pump, went bump again and bump again after, like it was remembering. And then I opened my eyes.

Lucy.

No.

Lucy.

No, no.

Lucy. Lucy! Lucy, Lucy, Lucy!

‘Lucy?’

‘Clod! Bloody Clod!’

‘Lucy, oh Lucy. It’s you.’

‘Whoever else?’

‘You’re living!’

‘Yes! Yes! Are you?’

‘A little bit.’

‘Bloody hell, this ain’t no time to sleep!’

‘You hit me!’

‘How else would you know it’s me?’

‘You’re always hitting me.’

‘Look what I got you.’

‘James Henry Hayward.’

‘Oh plug, I hear you. How ever did you …’

‘Never mind now, that thing up there, I think it’s looking at us.’

No time, leave us alone, leave us together a while. Can’t you? But no, no, something comes at once to break us apart.

‘It’s smelt your plug I think.’

‘It’s my plug.’

‘It wants it.’

‘Well then, in truth, it’s James Henry, not a plug after all, but, yes, I do believe it wants it.’

It creeps forward now, dropping little bits over us as it comes, small screws and pins and nibs, a rain of little things, coins, rivets, which then hop back to the big massing. I think it will land on us, on the whole, don’t you? It’ll drown us. Arms of it stretch forward to snatch from us, ten arms and more, all creeping to us, one rushes out and grabs the candleholder, dear Eleanor Cranwell, and steals it back inside its bulk.

‘Oh let us alone!’ I cry.

‘Clod,’ Lucy says, all that red, such a face, oh that dear face. ‘I’m right glad to have known you!’

And she kisses me hard on the lips, and then takes my plug from me. And goes. And I’m alone again without her.

Lucy, one last time

I’ve took it, took his bloody plug, I must take it away to stop that heap crushing down on him. To save him.

‘This is what you’re after!’ I cry at all that mass of bits. ‘Over here!’

It cracks and spits, there’s great screeching from the inside of it. All those many things, cracking and smashing towards me, but away from Clod, that’s the main point of it. Away from him.

‘Help! Help! The fire! We’re in here!’ How they do caw, the Queen and her company. I’ve got other worries.

‘Come ’ere, you great bully!’ I call.

It shrieks and roars, it smashes bits of itself, spools and needles and pins and nails and tacks and screws and bolts and scissors, there’s a great crashing and thumping and scraping and then it just stays there, a great wave paused at its height right over me. And then like rain it begins to spit at me, little drops of that great wave do plip and plop over me, only thing is, those drops of that great heavy wave, they hurt when they fall and how they do cut into me.

It sends glass shards into me.

It sends small screws, bits of saws, needles that bleed me, nails that cut at my face. I’m a pin cushion now, it’s playing with me, dotting me, such new freckles, writing over me in my own blood, sending bigger things now, sending books hurled with such force, sending whole plates, sending bookcases and chamber pots, sending saucepans to break me, sending a hammer’s head, and more and more, a bedhead clattering before me, a whole chimney stack smacks into my side, but I’m still holding it, that plug, I still have it, but I look up.

Oh then it’s coming now. That wave. It comes.

From Inspector Harbin

Now I might, now I must shoot the red-haired child, whilst there is still a chance. One brief chance; now do I aim. Steady. Steady.

Now might I. Now shall I. That thing of things is all looking at her now and now I shall do it.

‘Be a button, be a clay button!’

I flick my fingers, her mouth makes an astonished O and her whole body falls down into the shape of that mouth’s O. A button again.

Then a shot, fired into the mass.

A moment later the great thing is upon her and there is nothing more to see. The plug and the button quite consumed.

From ill-faced Georgie on Speaker’s Green

The strange man hops about, like a frog, screaming at people.

‘Rippit! RIPPIT!’

And whoever he screams at, bursts into flames.

From Umbitt

How hot it grows, how hot! I sweat so, my fingers are wet with blood and sweat. It’s regrouping again after that last tumble, whither shall it head now I wonder?

Clod is fumbling to his feet, pulling himself up. Calling for his button. Wailing and weeping.

The Great Gathering is smashing against the wall, hurling and breaking.

Nothing can stop it now, I think, nothing can ever stop it.

‘Now, Clod, call all your things, pull Lungdon down, drown it in the Thames!’

But he just screams for his button, his Lucy he calls it, while the great thing comes on.

‘Stand back!’ I call. ‘Stand back I do command you! I am Umbitt!’

It stands up, it makes a noise as if in mockery of me, it repeats my name in clinks and scrapes.

‘Ummbeeeettt. Umbeeeeeeettt.’

I see it now, so clear, I see it in all its voices, as it speaks to me in its many noises, as if I can hear as Idwid did and Clod. Here are all the dead, all the turned of Foulsham and Lungdon, all Iremonger birth objects here collected, all the ghosts assembled. All my murdered, oh so many hundreds of them. I did all to protect the family. I had to, it must be done. It is not like any Gathering I have ever known, all gatherings before had but one object spinning in its centre, maddening the rest of it, calling to action, one heart that thumped, but this, this Gathering has thousands of hearts and all do point their fury towards me.

‘Him!’ I cry. ‘Get him, get Clod! Leave me alone!’

It groans and smashes.

I face it, and it, all the girth and weight of it, doth face me.

From deep inside it spits something out. That thing comes rolling towards me, it is a small, spinning thing. What is it? I cannot say, it spins and spins so. It slows now, it slows and stops in midair.

It is a cog, a small, rusting cog, an insignificant thing. It’s calling to my cuspidor. It’s inviting it to come in.

‘No!’ I say. ‘No, never. You shall not have it.’

I hold it up, I hold it high, as high as I can above me.

‘No, this is mine, mine, I say.’

But I feel the tug of it, I feel the pull of it.

The Gathering is coming towards me now, the cog has darted back in, the great massing is sloping down, it is about my feet now, all about my feet, and now it begins to rise higher.

‘Mine! Mine, all mine!’ I cry.

At my ankles, at my knees and rising higher.

‘Get back, get back, I command things!’

They fall in about me, rising higher, more and more and more.

‘It is my one thing,’ I cry. ‘Have mercy, leave me my own one thing.’

It is at my hips now and rising about me, how it squashes me, how it crams against my body, cutting, smashing, pressing, breaking, trying to rob me of breath and birth object.

‘My own cuspidor, that my own father gave me.’

How it rises, at my chest now, I am in the very centre of the Gathering and it climbs and climbs to get my cuspidor. I am drowning, drowning in things!

How they crush me, crush me, they push hard against me, I feel them pushing at my ribs, up to my neck now, I shall burst with all this weight about me.

At my head.

How it pounds and smashes against my skull.

Only my hand, only my outstretched hand now is above the huge clot of Gathering, only that is unmolested. As I hold, whilst I may, my own cuspidor above the mass. But then oh then, my fingers so slippery with blood, only then the thing, my thing, my very dear cuspidor, moves in my fingers, I cannot keep hold of it and it dances in my fingers, it will not keep still, and then it stops and then, then of its own will, it jumps in, into the Gathering and makes no great cry as it lands, merely the smallest clink.

And then all great objects do pound against me.

And I burst.

Victoria Regina

Not as quiet as a clam, not any more. I weep, a Queen weeps in fear, in terror of what most unnatural events I have espied, and of the heat and of my own approaching death. I have seen such things, such things this morning, and never shall I see another afternoon, of that I am certain. I, Victoria, have seen objects bully and dance of their own accord, I have seen rats spin into people, I have seen ugly magic.

The fire is coming through at the windows. I shall be a roast Queen any moment, like any goose or turkey, like a guinea fowl, like a pheasant, like mutton. Such royal meat.

It’s crushed the old man, the Iremonger patriarch. I cannot say I am sorry for that, but there are so few of us left now, some MPs and Lords, the princesses at my side. It shall come for us, I do feel it. The Duchess of Teck has been turned into a common boot scraper. I shall be brave. I’ve made up my mind to be brave.

For now the great big thing is still. A massive mound, a heap in the centre of the Chamber of the House of Lords.

It has stopped, the great thing, and points every sharpness towards the one remaining Iremonger. It is the boy, the frail boy, blood down his side, tears on his face, so pale, such a little life left in that one. It makes me think of Albert again, I should perhaps even like to care for this poor child. He stands as tall as he can and walks a step, two, up to the great conglomeration. It is David and Goliath, but I fear for the ending so. I cannot bear to look, and yet I must for the sake of this stalwart child, one must. More than the unhappy Light Brigade is he to me at this moment, more than Wellington and all his swagger. I’ll pass over Lord Cardigan and Lord Raglan, lose Gough, Cathcart, Canning and Burgoyne in favour of this single child, standing before a poised army.

It has begun spitting at him, throwing out the sharp objects. I know this behaviour now, it seems to do this before it pounces; the horrid thing to play with him so, he is cut on his face, in his ripped clothes, blood down his side, but he still stands, he even moves a step forward, and another. He stands as tall as he can, perhaps he seems a little older now.

He is speaking to it. Whoever is this child?

Clod and Plug

‘I am Clod. Clod the fool. Clod the simpleton. You are all in there, I do hear you all. Please don’t spit so, it hurts, you see. I do hear you, I do hear you all. Oh the great agony of objects. I’m coming forward now, another step.’

It spits some more, an awl drills into my hand, an iron tumbles to my thigh, but I go forward another step.

‘I must earn my trousers,’ I say.

A pocket knife is launched from inside it and rips my ear.

‘Hallo, Lucy, you’re in there somewhere I know, and I love you.’

I go forward another step. What windows have remained shatter now, and burst inwards because of the fire that so, so wants to come in to us. But I must focus now, I must be more focused and thinking and feeling than ever I was before. Another step.

A chair kicks me, some chests spit their drawers at me but I manage to push them down. Another step. I am so close to it now, it is but a few inches ahead of me and may collapse upon me and suffocate me as it did to Grandfather, but not yet, it has not yet. I lift my hand up towards it, it backs away a little and shrieks and whirls and clatters inside.

I have a bullet within me, put there by my cousin. Such fury in him, because I was the one who turned his toastrack. Yes, I do understand now, it was I that did it. All along the answer was there, if I had only fathomed it. And if I did it once then perhaps I might again. I do begin to comprehend, I must have done it in my upset in the first London, yes London, it is called London, yes in that first London house, to that bullying red-haired servant’s birth object. And so why not again? Why not a hundred times, a hundred thousand? Again and again.

I put my hand closer.

I touch it. It recoils but does not fall. I put my hand in it, deep, deeper, up to my elbow, up to my shoulder, up to my chest, I feel about inside it and how it chatters and moans. I feel for it, I search for it, my hands so ripped and bleeding; where is it, where, where, come, come, do come now.

I feel a chain. I pull on it, I pull and pull.

My bloody hand is back out now and with both hands do I pull and pull and pull upon this chain, it is so long and rusted, made of so many different links. The Gathering goes wild and shifts and screams, and spins hurriedly about. Still I pull, I pull and pull and pull, it screams and spits as I pull now, now. We may all exist together, I think we can. Come back, come back. Let me feel you.

‘My plug, my plug,’ I say. ‘Give me back my plug! Surrender it, I do command you. For I am Clod, and I know things!’

Still I pull, still it tugs back, it screeches and moans and loathes to give it up.

But I have it now! The chain is coming to the end; I pull, pull, pull out my plug, I tug it out!

And it comes!

Falling through the great collection is not a small, universal bath plug made of finest India rubber, but it is hair I have hold of, human hair, and out comes a child, about ten years of age, and his name is –

‘James Henry Hayward, James Henry Hayward.’

And with that boy on the ground now all the mound, as if in a horror of the sight, heaves upwards, it lurches and shrieks and cries shrilly, bits banging together, such clattering, such a knell, like all of London’s bells calling out at once – and then it stops and then, oh then, just then it stays still and it tumbles in a great smashing to the ground.

Not one object now, not one heaving collection of things, but many separate things, each its own thing and these things on the ground, here and there thickly about, do spin and rattle of their own force and they do, oh they do one and all, grow up now, grow and suffer their change, and out of them, out of the massing: the people, the people come. Oh the people come back. All, all tumbled back into people. And all in their confused heaps do call, cry, whisper, shout, mutter, murmur, weep, sob, talk out their own names,

James Henry Hayward. Eleanor Cranwell. Perdita Braithwaite. Gloria Emma Utting. Percy Hotchkiss … Emma Jenkins, Sybil Booth, Lester Ritts, Mary Ann Stark, Giles Bickleswaite, Theobald Villiers, Elsie Bullard, Leona Rice, Lloyd Walters, Elliot Murney, Dorothea Towndell, Matthew Stokes … Valerie Turner. Augusta Ingrid Ernesta Hoffmann. Little Lil. Lieutenant Simpson. Polly. Mr Gurney … Alice Higgs. Mark Seedly. Amy Aiken. Geraldine Whitehead.

And

‘Lucy Pennant. Lucy Pennant.’

As if in answer to the flaming of her own dear hair, the flames fall into the Chamber. The flames seize the wooden panels and lap them up, burn the benches, lick the carpet, swarm one and all, all over.

‘Oh dear,’ I say, ‘it’s fearful hot.’

And then on top of that a terrible, thick awful suffocating stench, not of burning, of burnt things, but a stronger, all-encompassing reek of filth and excrement, of all foul things, and then a great explosion of dirt comes over us, filth, swamped with filth, and the hiss of the fire going out.

‘Lucy Pennant, swidge, Lucy,’ says Lucy.

The Queen as witness to the source of the smell

The Chamber of Lords is covered in effluent. Every inch of it, and my person too. There is a strange new giant come into the room, he seems the filthiest creature that ever can be conceived, like some dirt scraped up from the very bottom of hell.

‘Bin,’ he cries and indeed he has emptied a bin, a bin no doubt the size of all London over us, but it has saved us, I do feel.

‘Late. Am I?’

Lucy trying to speak

‘Lucy Pennant! Lucy Pennant! Binadit!’

‘Benedict please to call.’

‘Lucy. Benedict.’

‘Botton?’

All around every one of us is covered in dirt, in rubbish and foul muck. The Queen has horse dung about her. The very Queen.

But beneath all the dirt and grit the Queen is clapping. And they are all clapping now, like we were in the theatre and the curtain’s just come down.

But Clod, he falls back then, Clod, he hits the floor, poor sack of Clod, bleeding so. It was all too much, too much for his punctured frame.

The Queen’s speech to Parliament

‘Help! Help! Someone help him!’