The Natives are loyal, happy and contented; they are

proud to be associated with the British Empire….

Here in Samoa is a splendid but backward Native race.

Major-General George S. Richardson, 19131

In his first year and a half as Administrator Richardson had alienated many people, European residents as well as Samoans. He saw himself as bringing Samoa the benefits of Western civilisation in such fields as medical care and hygiene, but his paternalistic and bureaucratic approach ignored the subtleties of the Samoan way of life. He was determined to replace communal ownership by private property and to reform the sexual behaviour of the Samoans by enforcing the Christian conception of marriage, but such policies were having complex effects he had not anticipated. On Savaii the Flahertys were amazed to observe Richardson’s bizarre strategies such as sending his public works engineer ahead of him to create the impression that he was planning to build a new bridge, which ensured that the chiefs prepared a great reception for his arrival. He brought a movie projector on his visits so he could screen a war-time newsreel which showed him acting as a guide to the New Zealand Prime Minister visiting the trenches in France. The interpreter would call on the Samoans to applaud whenever Richardson appeared on screen.2

In Lye’s village there were numerous jokes about Richardson as a wowser, for he had continued to enforce the total ban on alcohol introduced by one of his predecessors. Lye’s Samoan friends found a chemist in Apia willing to sell them yeast and other ingredients for a home brew called fa’amafu: ‘We had to bury it in cans to keep it hidden. It was the fastest fur-growing stuff for your tongue I’ve ever tasted, a very quick effect followed almost immediately by the most crushing of hangovers.’3 Lye was also contemptuous of Richardson’s puritanical attitude that sex had to mean marriage, but at the same time he had made a personal decision not to ‘get trapped into family stuff’ with any of the young women that Solavao was trying to pair him up with. Despite his intention of keeping his distance from the palagi he became involved with ‘a romantic red head in Apia, the daughter of a physician in the Island Hospital’.4 With her there was no risk because ‘she could look after the contraceptives and stuff perfectly’.5 However, the mere fact that Lye was living in a Samoan village was enough for other Europeans to assume that he was involved with Samoan women, and under Richardson’s rules this was a serious offence.

In Lye’s words: ‘Richardson called me up and said, “You can’t live with Samoans any more. We have an edict out. All Europeans with Samoans, out you go. Or else set up shop somewhere on your own with the whites. Too many half-castes around, and they’re causing a lot of racial trouble.”’6 (The issue of ‘half-castes’ was an obsession with Richardson, who saw them as responsible for the political resistance to his government.) Lye replied: ‘Sir, you’re barking up several wrong trees. One, I’m not running round with Samoan girls, much as I’d love to. Two, I’ve got people to back up the statement that I am here with a definite study project: Samoan design. And I can give you the names of anthropologists.’7 He invited Richardson to ‘come round and see my sketches of Samoan art some time’.8 The Administrator was furious and warned Lye that he was likely to be deported. Deportation and exile were the Administrator’s favourite tactics, and Lye was (in the later words of Monica Flaherty) ‘a type of person who would really have ruffled up dear old Richardson’.9

This encounter left Lye pondering how much time and energy he was prepared to spend fighting against deportation. He enjoyed the Samoan way of life but had stopped feeling any compulsion to make art, the activity that had previously been central to his life.10 ‘Gauguin and others have managed it but I was too young to sit around introspectively while there were so many marvellous things going on around me all the time.’11 As the months passed he became worried about his ‘gap of nothing in the way of ideas’.12 There was, however, truth in his claim to Richardson that he was studying Samoan design. Tapa cloth (as Lye described it) was ‘made from pounding the bark of the mulberry tree. It had a creamy panama-straw colour with a soft tactile quality all its own.’ For everyday wear tapa cloths were usually left plain because dyes stiffened them but for other uses there was a wide range of stylised patterns, applied by rubbing the cloth against a grooved, inked board (the upeti) or by painting designs freehand (which were often bold and brightly coloured).13 Lye took notes and made sketches of the best siapo (tapa) patterns.14 Despite their abstract appearance, many of the motifs had ‘descriptive names drawn from the natural world, such as breadfruit leaves, pandanus leaves, pandanus bloom, fishnet, trochus shell, starfish, worm, centipede, and footprints of various birds’.15 Such motifs were repeated with slight variations across the tapa cloth, creating visual rhythms. Tapa design encouraged the shift that had already started in Lye’s style away from modelling and shading towards images that were flatter, bolder, and more linear. He was also very interested in tapa designs from Fiji, Tonga, and Hawaii: ‘I think the best tapa cloths are the early Hawaiian. They’re knock-outs.’16

He was still studying the African art he had documented in his notebooks and one night he had a particularly vivid dream about it: ‘I was in a village seeing a Negro friend. We were both artists and he was showing me how to use an adze.’ They were making black wood sculptures and Lye was admiring the texture of the marks left by the adze. They talked of how traditional African art was in danger of dying out. Just then a war started between their village and the neighbouring one, and despite strenuous efforts Lye could not persuade his mentor to stay and continue carving. Suddenly a spear hit Lye and he yelled and woke up, only to discover that he had been stung in his sleep by a scorpion.17

At times he went up ‘on a kind of oil rig submerged in the middle of a coconut plantation to sit with a notebook and try to think about art and life’, but nothing much came of this.18 He missed having access to good libraries. His only source of art news was Time magazine which he borrowed from Father Diehl, an American priest popular with the Samoans.19 Time, which had begun publication in 1923, referred occasionally to modern artists though it did so with caution. In March 1924 Time said of Henri Matisse that his ‘crude nudes and restless still-lifes have long been flaunted before a sceptical public’.20 One early issue reported that ‘A piece of machinery is to be exhibited as a work of art at the Spring Salon’,21 and another cited the Ukrainian artist Alexander Archipenko as an artist who ‘experiments with bizarre media for sculpture — glass, wood, papiermaché and paint, polished sheet-iron reflecting surrounding men and things’. Time felt duty bound on this occasion to end by quoting a reviewer’s comment that ‘Only a fundamental degeneration could have produced [this sculpture], and it is an ominous sign when any sane human being finds it of interest’,22 but such stories were always music to Lye’s ears. Indeed, the longer he stayed in Samoa the more hungry he felt for modern art. He decided that if Richardson were to deport him, he would try to head for one of the centres of modernism.

As he reviewed the possibilities in his mind, the one that excited him most was Moscow. He knew nothing of the Russian language, but neither had he known Samoan. Time in its enthusiastic comments on the Moscow Art Theatre’s visit to New York in 1923 had said: ‘It is a very trifling barrier that the Moscow players use their native tongue. The reality and expressiveness of the performance make broader meanings as clear as daylight.’23 Since the 1917 Revolution, Russia had generally been viewed by other governments with fear and hostility. This attitude was strongly represented in the pages of Time, but even Time admitted that unusual things were happening there in the arts. Lye was not worried about Communism — indeed, he had heard some of his bohemian friends in Sydney talk about it enthusiastically, and the community he was living in at the moment had little interest in private property. But what interested him about Russia was less the revolution in politics than the revolution in art that seemed to have accompanied it. Reading avant-garde material in Sydney he had been astonished by a report on the activities of Vsevolod Meyerhold, a founding member of the Moscow Art Theatre who now had his own company. Imbued with the spirit of Constructivism, the Meyerhold group designed costumes, sets, and stage movements as though their plays were modern paintings in motion. Their work celebrated the machine as the symbol of the future, and conceived of the actor in terms of ‘biomechanics’ as ‘a rather wonderful engine composed of many engines’. ‘The new problem of the theatre [was] how to get this engine in full motion.’24 Meyerhold’s solution was a robust, physical style of performance developed from such precedents as the Commedia dell’arte.

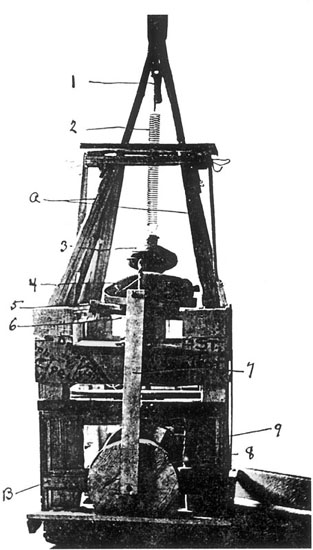

What sent Lye’s enthusiasm into orbit was Lyubov Popova’s set for Meyer-hold’s 1922 production of The Magnanimous Cuckold.25 For this outrageous sexual farce, Popova created a large, machine-like construction which combined a propeller (representing a windmill) with steps, wheels, and ramps reminiscent of a children’s playground. In her words: ‘The movement of the doors and window, and the rotating of the wheels were introduced into the basic score of the action; [and] by their movement and speeds they were to underline and intensify the kinetic value of each movement of the action.’26 In the course of the play the wheels and propeller whirled round with increasing speed to mark the accelerating emotional climaxes.27 Lye saw the set as a giant piece of kinetic sculpture even more impressive than the work from St Elizabeth’s. If he could get to Moscow he would surely find kindred spirits at Meyerhold’s theatre. He liked the prospect of sampling life in a big city that was seething with political and artistic experiment, and while there were terrible shortages of food and supplies he was used to living rough. Language was again going to be a problem but Meyerhold’s highly visual style of production made him hopeful he could communicate as a fellow artist.

By now Lye had become sufficiently skilled in the handling of a small outrigger to take it through the reef surrounding his island, out to the open sea. He would do this whenever he saw a big ship anchored off the reef.28 ‘I would go up and ask to see the mate. Or the captain. “What for?” “Well, I want to know if you need a hand — anybody jumped ship? — because I want to work my way to Vladivostok.” “What the hell do you want to go to Vladivostok for?” “Well, if you must know, I aim to cross over to Moscow. By the time I get to Moscow, I’ll know a bit of the language”. He would say: “Well, you’re out of luck”.’29 When Lye realised he was not going to find a suitable boat, he decided to bargain with Richardson for a trip that would take him part of the way.30 The Administrator was so eager to get rid of Lye that he offered a free passage to New Zealand. But to Lye this was a backwards step, and so there were more heated negotiations and finally he was offered a trip to Sydney. According to Lye, Richardson made sure that such a situation never arose again: ‘From that time on, nobody was allowed to go to Samoa unless they had the fare to get back.’31

When Lye left Samoa around the beginning of 1925,32 he had not been there long enough to develop a thorough inside knowledge of the culture but he had at least got beyond tourist stereotypes and the experience had made a deep and lasting impression on him.33 His Samoan friends with their customary generosity gave him wonderful presents such as a large bouquet of flowers made of intricately woven coloured grasses and some inlaid tortoise-shell rings. He had to talk them out of giving him their finest block-printed and hand-painted tapa cloths.34 From Apia he took a small ferry to Pago Pago and then got a free first-class passage on an American boat to Sydney.

The image of his departure that he would remember most vividly was seeing a Samoan about the same age as himself on the deck of the ferry. In Lye’s words: ‘I think to myself: I am leaving Samoa and he’s going to another island. Wearing a tapa lavalava in the ancient voluminous style he finishes his banana-leaf-wrapped cigarette, and unwrapping his bundle of tapa he lets his head rest on deck and winds the tapa around himself and self-consciously cocoons himself down.’ Around him were bags of scented cargo, such as the deep chocolaty smell of cocoa beans and the slightly rancid smell of copra. Under a full moon the whole scene began to settle into a design: ‘The moon behind the sleeping Samoan is getting brighter, the sea colour fades out of my mind and is replaced with the colour of the wooden deck’ — an intense moonlight glow he would remember always as like ‘the creamy colour of tapa’.35

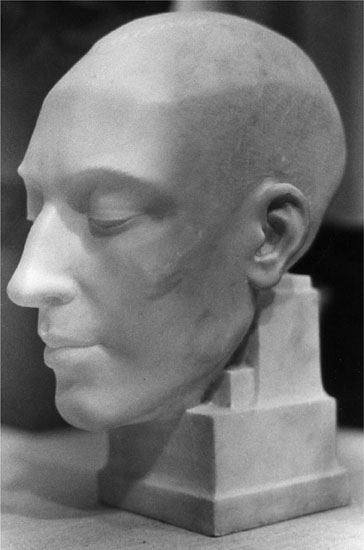

The marble portrait head of Lye by Sydney sculptor G. Rayner Hoff, which won the Wynne Art Prize in 1927. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

A photo of Lye while he was modelling for the sculpture, taken by the sculptor’s brother, Thomas Hoff (circa 1925). COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

Lye’s bookplate for the pianist Nigel Pearson, Sydney, circa 1925. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

Three pencil drawings made by Lye in Sydney, circa 1925. The older man is the poet Geoffrey Cumine. The woman is Mary Brown, and Lye described this drawing as an example of his last representational style before his art became more ‘primitive’ and abstract. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

Lyubov Popov’s stage set for the Meyerhold Theatre production of The Magnanimous Cuckold in Moscow in 1922. Lye was so excited by a picture of the set that he made plans to go to Moscow. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

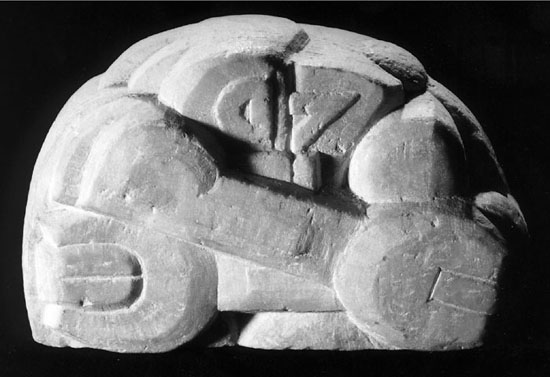

It was this photograph in Edwin J. Kempf’s book Psychopathology that inspired Lye to start making kinetic sculpture. Kempf’s caption described the object as a ‘Copulation fetish by [an] impotent negro paranoiac’ instructed by God to build the ‘first church of perpetual motion’. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

Lye’s wooden carving ‘Tiki’ (or ‘Hei-Tiki’), Auckland, 1922. PHOTO JOHN B. TURNER

‘Unit’, a marble carving Lye made in Sydney circa 1925, representing a man and a woman clasped in a tight embrace. PHOTO BRIAN DONOVAN

Sculptor Kanty Cooper, who worked alongside Lye in Eric Kennington’s studio in London in the late 1920s, specialised in the direct carving of wood and stone. These examples of her sculpture include the bold ebony carving (above) of a child on a mother’s shoulders. COURTESY KANTY COOPER

The ‘Euripides’, on which Lye worked his way to London as a stoker in 1926. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

Eric Kennington and A. P. Herbert’s barge Avoca (nicknamed ‘The Ark’) sailing down the Thames. Lye lived on this barge after his arrival in London. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

Lye, Jack Ellitt, and Celandine Kennington by the Thames. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

Jack Ellitt and Doris Harrison. From 1927 Ellitt had lived with Lye on the Avoca. After Ellitt and Harrison got married they lived on the Ringrose, a barge moored alongside the Avoca at Hammersmith. COURTESY JACK & DORIS ELLITT

Jane (Florence Winifred) Thompson, who later became Jane Lye, in Hammersmith. COURTESY JANE LYE

Lye going to the Black Lion pub for beer. PHOTO JOHN PHILLIPS. COURTESY LEN LYE FOUNDATION

This photo and caption appeared in the Auckland newspaper The Sun on 19 May 1928 describing Lye’s contributions to a Seven and Five Society exhibition. The edge of his batik ‘Polynesian Connection’ is visible at top left.