The dinner was set on a velvet cloth embroidered with silver threads. A silver tray was placed on a six-legged silver stand, decked with salads, caviar, olives, and cheeses. The salt, pepper, and cinnamon shakers were inlaid with precious gems. Lemon juice was served in a carved crystal pitcher. In the center was a silver trivet. Around the tray were delicately embroidered silk napkins wrapped in rings made of mother-of-pearl with diamonds.

—Leyla Saz, Haremin Içyüzü (1921)

Afiyet şeker olsun. (May your taste turn to sugar.)

Each meal started with those words before anyone touched a morsel. Eating was not a casual activity in the harem, but an elaborate ritual. All day long, an endless stream of confections and sherbets passed through the corridors to the apartments of the Valide sultana, the kadins, and the favorites, most of whom cherished a sweet tooth.

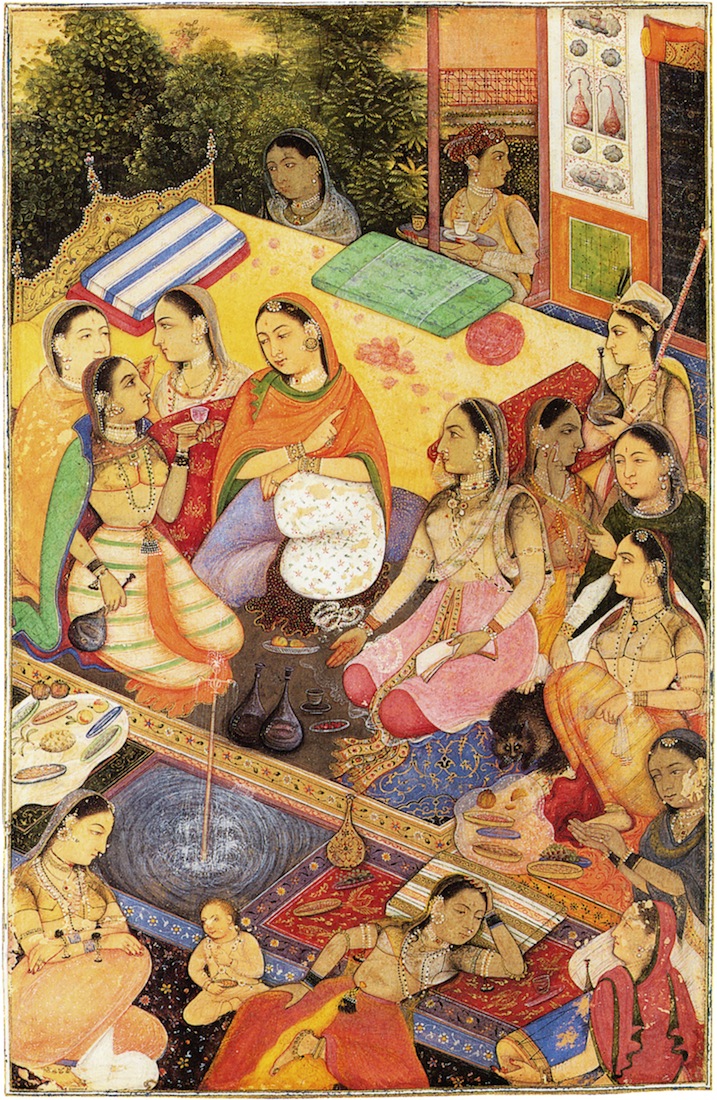

Unknown artist, Harem Scene at the Court of Shah Jahan (album leaf), second quarter of 17th century, Ink, colors and gold on paper, 77⁄8 × 5 in. (131⁄8 × 81⁄4 in. sheet), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915

Some sherbets required a seventy-mile trip from Mount Olympus, where snow from the great ice pits was wrapped in flannel and carried to the Seraglio on mules. According to Evliya Chelebi’s travelogue, Seyahat-name (1630–72), the snowmen wore turbans made of snow, and mounds of the purest snow gathered from Mount Olympus, as large as cupolas, were piled on wagons and pulled by a file of seventy to eighty mules. In his eighteenth-century Tableau général de l’empire ottoman, M. de M. D’Ohsson describes the Gülhane (Rose House), where sherbets and preserves were made: “The care that they took in making sherbets was as intricate as the French took in making their wine. Sherbet would usually be a concoction of different fruit juices, as well as essence of flowers, such as rose, gardenia, pansy, linden flower, and chamomile; and it was perfumed with musk, ambergris, and aloes.” Sherbets were made from violets and roses, and coffee flavored with cloves, cinnamon, and rose petals.

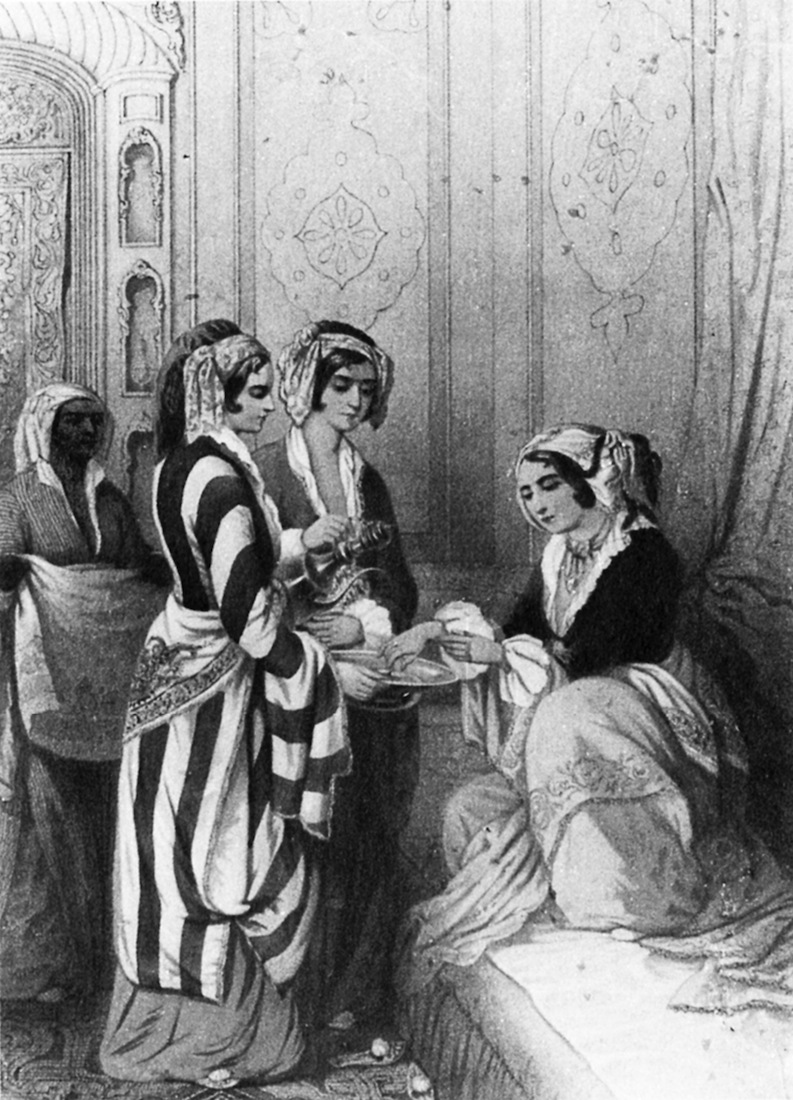

Before being served, the sultan’s food was tasted for poison in the Kushane (Bird House). Stone shelves lined an entire wall in the Food Corridor, where the black eunuchs gathered the brass trays from the royal kitchens to be distributed in the harem. The food was placed next to the doors of the sultana’s apartments. Servants carried the trays over their heads and placed them in the center of the room. Well-trained odalisques waited on the Valide sultana, while the kadins and the favorites who had been granted their own apartments ate out of silver trays placed on small low tables.

Not until the reign of Mahmud II (1808–39) was silverware introduced to the harem. Before this, the women ate with their hands—maintaining that taste is first transmitted through the fingertips. This happened to be a stylized and refined art form that odalisques were carefully trained to perform with delicacy, lightness, and grace. They manipulated the fingers in much the same way as the Japanese do in the tea ceremony, every movement—reaching, bending, turning—a dance of extreme skill and precision. They reserved the right hand for food (the left was for unclean tasks), using only three fingers and scarcely getting the tips soiled.

After a meal, servants delivered a silver pitcher and basin for washing the hands, and embroidered towels for drying them. Then it was time to recline on the cushions and smoke. Tobacco was of very high quality and one of the greatest joys of harem life. Women smoked profusely and indiscriminately—except in the presence of men. The novices, who were not allowed to smoke, did so secretly. Elizabeth Warnock Fernea, in Guests of the Sheik (1965), describes the conflict over tobacco between two wives in an Iraqi harem:

“It is better not to smoke,” said the old woman who had guided me to Selma’s door. “Haji Hamid does not like women who smoke.”

Selma looked at the old woman. “Kulthum,” she said, “Haji Hamid is my husband as well as yours,” and then deliberately lit cigarettes for herself and several others.

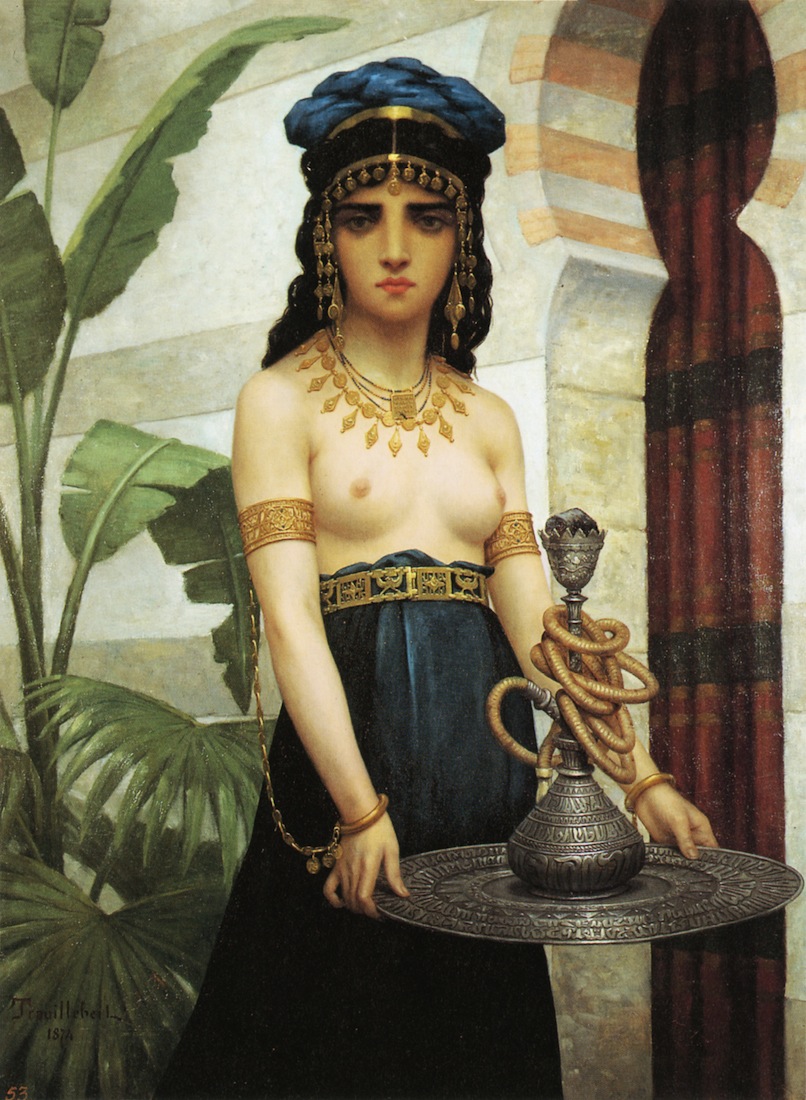

Chibouks and nargileh (water pipes) added elegance to the smoking ritual. Théophile Gautier himself indulged:

Nothing is more propitious to the fostering of poetical reveries than relaxing on the cushions of a divan and inhaling, in short intakes, this fragrant smoke, cooled by the water through which it moves, which reaches the smoker after being propelled through red or green leather tubes that intertwine with his arms, making him somewhat resemble a Cairo snake charmer playing with serpents.

Paul-Desiré Trouillebert, The Harem Servant, 1874, Oil on canvas, 511⁄8 × 381⁄8 in., Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nice

The gustatory excess that characterized harem life fattened the inmates. “They have … crooked feet, and this comes from sitting on the ground cross-wise,” Bassano da Zara observed. “For the most part they are fat because they eat a lot of rice with bullock’s meat and butter, much more than men do. They do not drink wine, but sugared water, or Cervoza (herb-beer) made in their own manner.” By “cervoza” da Zara must have meant boza, a fermented barley drink, deliciously sour, served cool, sprinkled with leblebi (roasted chickpeas) or cinnamon. (The best way I know to describe the taste is something like sake and tapioca blended together.) When I was a child, “boza men,” dressed all in white, strolled the streets on autumn nights, bellowing, “Boza, boza, Akman’s boza, marvelous bozaaaa!” They carried on their shoulders brass buckets full of this sweet and sour drink. We would run out to the street to have boza poured into our tall glass mugs. When I recently returned to Turkey, these calls of “boza, boza, marvelous boza,” the last cry of the Ottoman Empire, no longer echoed through the streets. The drink was about to disappear forever, but the enterprising Akman and other boza makers bottled it to sell at pastry cafés.

Lunch and dinner were the big meals, always a feast: lamb dishes, börek (pastries filled with meat, cheese, or spinach), pilav, eggplant dishes, choices of vegetables cooked in olive oil, and always lots of rich desserts and compotes. And then a mid-evening snack of fruits and sweet desserts that had voluptuous and erotic names like “Lips of the Beauty,” “Hanum’s Fingers,” “Ladies’ Thighs,” or “Woman’s Navel.”

Many of the harem women were accomplished confectioners. Turkish delight was the most craved of all sweets; several thousand tons were—and still are—exported annually. This chewy paste is made from the pulp of white grapes or mulberries, semolina flour, honey, rose water, and assorted nuts, rejoicing in the name Rahat Lokum—“to give rest to the throat,” a rest absolutely essential after a harem feast.

LIPS OF THE BEAUTY

| Syrup: | Rolls: |

| 21⁄2 cups sugar | 1⁄2 stick butter |

| 1 tsp lemon juice | 13⁄4 cups water |

| 3 cups water | 11⁄2 cups flour |

| 1 tsp salt | |

| 2 beaten eggs & 1 egg yolk | |

| 1 cup safflower oil |

Make a syrup, mixing together the sugar, lemon juice, and water; boil for 15 minutes, stirring occasionally. Set aside to cool.

Heat butter in a saucepan until it begins to change color. Add the flour and the salt to make a paste and slowly pour in the water. Cook over very low heat for about 10 minutes, stirring constantly. Remove from heat and cool to room temperature. Add the two eggs and the yolk slowly, and beat well with a fork until blended. Turn on a floured board and knead thoroughly. Divide the dough into walnut-size pieces and shape into rolls folded over like Parker House rolls, to resemble lips. Heat the oil and place the lip-shaped rolls in it. Fry on both sides until golden brown. Remove and drain off excess oil. Pour the syrup over it and serve warm.

After the sweets came the coffee ritual. One attendant brought in the coffee, another carried a tray with diamond-studded accoutrements, and a third actually served the coffee. Turkish coffee was not grown in Turkey but came from Yemen—and initially met a hostile reception. Considered a source of immorality, it was banned for many years. By the mid seventeenth century, its virtues were extolled with deliberate extravagance in such works as Katib Chelebi’s The Balance of Truth (1650), which claimed, among other things, that boiling-hot coffee miraculously causes no burns:

Coffee is indubitably cold and dry. Even when it is boiled in water and an infusion made of it, its coldness does not depart: perhaps it increases, for water too is cold. That is why coffee quenches thirst, and does not burn if poured on a limb, for its heat is a strange heat, with no effect.

To those of moist temperament, and especially to women, it is highly suited. They should drink a great deal of strong coffee. Excess of it will do them no harm so long as they are not melancholic.

What distinguishes Turkish coffee is its texture of very finely ground grains, almost pulverized, and its idiosyncratic method of preparation.

TURKISH COFFEE

1⁄2 cup water

2 Tbsp sugar

2 tsp pulverized coffee

Pour cold water in a jezve (a small cylindrical pot with a long handle). Add sugar and coffee. Stir well. Place over low flame and heat until small bubbles barely begin to form. Remove from the flame and pour off froth into demitasse cups. Bring to boil, but do not allow it to boil over. Remove from flame. Pour coffee over the froth to fill cups and serve.

It seems very simple, but making it perfectly is a challenge. It has to have just the right amount of froth, and this is a function of timing.

Coffee making was a crucially important part of a young woman’s life, since her merits as a wife were initially and continually evaluated on the basis of how her coffee tasted. She painstakingly practiced to get it just right, in order to win the heart of her beloved’s mother.

I myself went through an intensive training when I was about nine years old and assumed somehow that this custom of one generation of women teaching a younger generation would survive forever. But this, too, is a vanishing tradition. Indeed, Turkish coffee is nearly obsolete. Everyone has been favoring “Nescafé,” which means any kind of instant coffee, and Starbucks has found its way to the cafés.

Drinking alcohol is taboo in Islam but for the most part was tolerated, except during the reign of certain sultans, such as that of Murad IV in the seventeenth century, when not only alcohol but also coffee and tobacco were prohibited. But under any circumstances, it was not considered good form for women to drink alcohol. They did serve the men raki, a beverage distilled from grapes and flavored with anise, similar to pastis, ouzo, or sambuca. This colorless liquid turns a milky white color when ice or water is added to it. No mild libation, it is called “Lion’s Milk.”

In contrast to the other meals, harem breakfasts were simple and modest, consisting of clotted cream, honey, feta cheese, jams, and olives, with strong Russian tea—never coffee. In fact, it is still considered inappropriate to order coffee for breakfast. Leyla Saz recalled in Haremin Içyüzü: “Certain cream cheeses and feta cheeses were made in silver containers and delivered to the palace in baskets. These special treats were for the Royal Palace only and were never sold elsewhere. In return for these delicacies, the merchant would be rewarded with stuffed mussels.”

Cleopatra is reputed to have had twenty-four kitchens, one for every hour. In the Seraglio there were ten double (or twenty single) kitchens allocated to the sultan, the Valide sultana, the kadins, the eunuchs, and other members of the court—sufficient to impress Ottaviano Bon in his Narrative of Travels (1604):

The kitchen utensils are a sight to see, because the pots, cauldrons, and other necessary things are so huge and nearly all of copper that of things of this kind it would be impossible to see any more beautiful or better kept. The service of dishes is of copper tinned over, and kept in such continual good repair and so spotless that it is an amazing sight to behold. There is an enormous quantity of them and they are a very considerable expense of the Porte, and especially because the kitchens provide food for so many both within and without, particularly on the four days of the Public Divan (a time when an extra 4,000 to 5,000 would be fed, in addition to the usual 1,000 or more).…

The royal kitchens had 150 cooks, the most prestigious position among them being the dresser of the sultan’s food. According to Nicolas de Nicolay, who visited the Seraglio in 1551, “Those of the privy kitchens have their furnaces apart, to dress and make ready the meat without the smell of smoke, which, being sodden and dressed, they lay in platters of porcelain, and so deliver it unto the Cecigners, whom we do call carvers, to serve the same unto the great lord, the taste [for poison] being made in his presence.”

The wood to keep the braziers burning and to stoke the fires in the harem kitchens came from the sultan’s own forests. Thirty enormous lumberjacks in the service of the Seraglio sailed the Black Sea regularly to keep the stockpiles high, taking slaves along with them to cut and load the wood.