The Oriental woman is no more than a machine: she makes no distinction between one man and another man. Smoking, going to the baths, painting her eyelids and drinking coffee. Such is the circle of occupations within which her existence is confined. As for physical pleasure, it must be very slight, since the well-known button, the seat of same, is sliced off at an early age.

—Gustave Flaubert, Letter to his mistress, Louise Colet (1850)

Prior to the twentieth century, women were segregated in almost every Moslem household in the Ottoman Empire—even in a few of the Christian and Jewish ones. While the wealthy lords kept opulent harems that were smaller versions of the one in the Seraglio, with numerous eunuchs and odalisques, even a few of the poor might keep two wives in one small room, a mere curtain separating them.

Unlike the sultans, ordinary Moslem citizens generally married daughters of other Moslem citizens. These women had been born into and stayed in their father’s harem until they were married. Then they moved into their husband’s harem, managed by the man’s mother, the Valide. (“Harem” here does not necessarily imply the practice of polygamy but rather that the women of the house lived separately.)

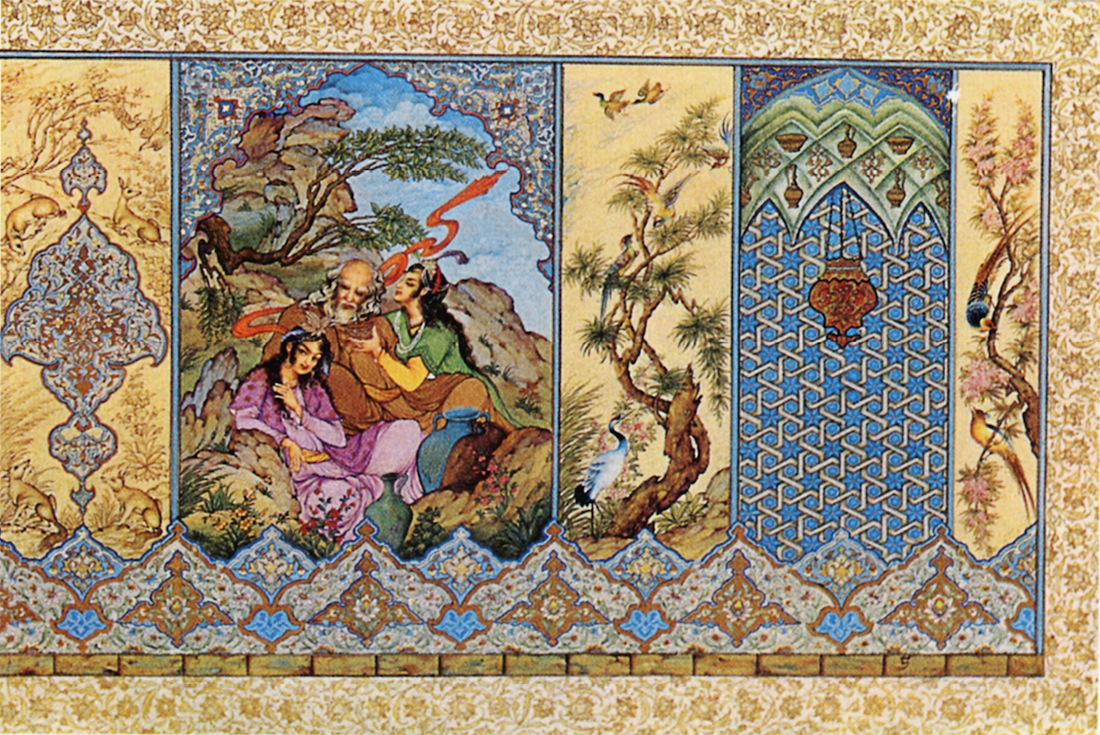

Edmund Dulac, Illustration to Quatrain LXXII of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1909), Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York

Alas, that Spring should vanish with the Rose!

That Youth’s sweet-scented Manuscript should close!

Marriages were arranged by families, and each man was allowed four legal wives under Moslem law (if he wanted to comply), whom he was expected to keep in the same style and lavish equal affection upon. However, the first wife was considered the most important and often had greater legal privileges. In addition to the four wives, girls were available for purchase and brought into the harems as servants. On rare occasions the men had sexual contact with or even married these servant women to legitimize their children.

THE GO-BETWEENS

Since men and women did not associate socially, marriages were arranged by görücü (go-betweens), “agents” who visited harems, studied the merits of a certain girl, and passed their judgment on to the man’s family. Sometimes these arrangements were orchestrated between relatives to strengthen the bonds of kinship. The betrothal of first cousins was and still is prevalent in some Islamic countries.

Görücü were still operating during the 1960s. Most of these women were self-proclaimed busybodies who prided themselves on their talent for matchmaking. They sought out pubescent girls for widowed, middle-aged, or unmarried men who seemed incapable of finding wives for themselves. Unannounced, the görücü showed up at a girl’s house. Islamic custom not allowing one to turn away a guest, the girl’s relatives would welcome the görücü—because that was their obligation. They served her coffee and sweets, acted polite, and made small talk. Meanwhile, the young girl would be hiding in the kitchen or in another room, until her mother or aunts invited her in. She would be required to make and serve Turkish coffee, since great importance was attached to her ability to brew this concoction. Her eyes cast down, she served the coffee to the görücü and her entourage, either leaving the room immediately after they had sufficient opportunity to scrutinize her or sitting silently on the edge of her seat, listening to the other women carry on.

My friends and I used to make fun of this primitive custom, but since we were living in a country still caught in uneasy change, it was inevitable that we, too, would encounter the görücü. I recall on several occasions peeking behind the door and watching these women come for older girls in the family. I became very familiar with the ritual and antics. Barely after I had reached puberty, it was my turn. I was incensed at their gall and resisted coming out to meet them, but the older women in my family, steeped in tradition, insisted that I present myself. In my rebellion, I did what I could to make myself unattractive, undesirable, and unwomanly—at least according to the prescribed standards. I dressed inappropriately, made bad coffee, and talked too much. It was a great relief when they left, but often a source of quarrel, since my women relatives felt I had misbehaved, and I myself was humiliated by having been subjected to this archaic ritual. Although they sympathized with me—and it was always understood that I would find and choose my own husband—they felt hurt to see the age-old tradition crumble and realize that they were its last relics.

ROMANCE

Despite the interference of görücü and the custom of arranged marriages, romance still smoldered in the imagination of young men and women. Pubescent girls, discovering their hearts for the first time, spent endless hours composing symbolic verses to imaginary handsome lovers. Thousands of small artifacts, such as flowers, fruits, blades of grass, feathers, and stones, were endowed with special meaning in the language of love. A few cloves, a scrap of paper, a slice of pear, a bit of soap, a match, a piece of gold thread, a stick of cinnamon, and a corn of pepper signified “I have long loved you. I pant, languish, and die with love for you. Give me a little hope. Do not reject me. Answer me with a word.” The girls often got so carried away with their fantasy lovers that when their arranged husbands came along, heartbreak was inevitable.

Two common Eastern fantasies depicted on Iranian postcards: lovers served food and wine by a houri—an image that also symbolizes cennet (paradise) on earth—and a dying old man surrounded by a harem of houris.

For their part, young men were also romantics: “I could see that he was terribly in love, for with Arabs, a very little goes a long way; and never being allowed to see the young ladies, they fall in love merely through talking about them,” observed Lady Anne Blunt in her 1878 journal.

Romance or not, families decided who married whom. My grandmother was promised to her father’s best friend when she was merely a child. When they eventually got married, she was fourteen and my grandfather was forty.

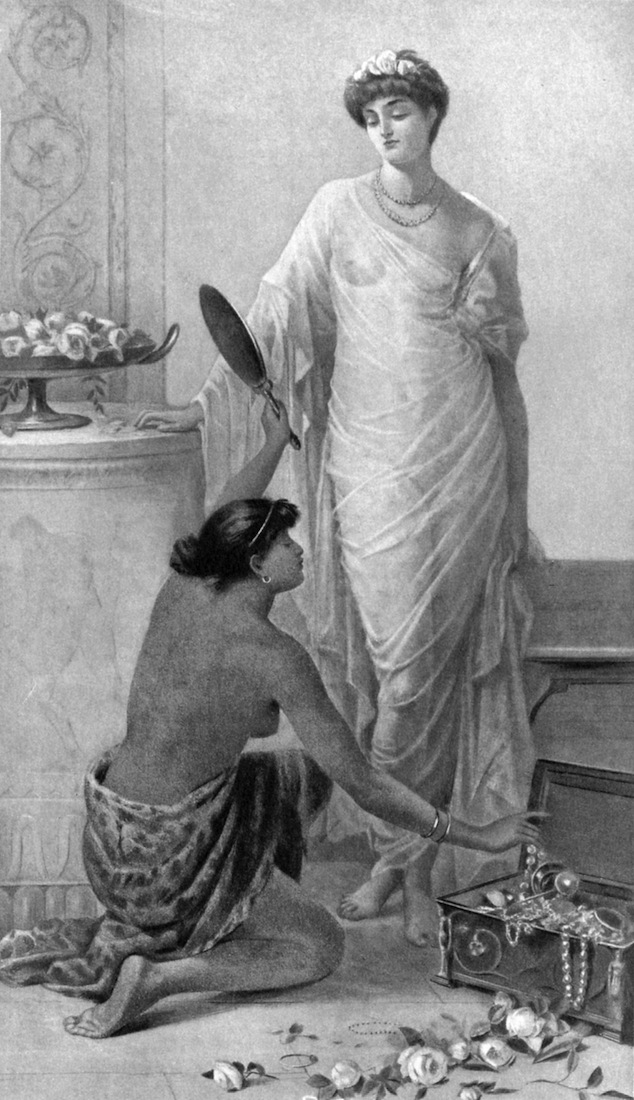

GIFTS

In the nineteenth century, if the husband-to-be came from a wealthy family, he would give his betrothed, as engagement presents, a silver mirror, perfumes, spice trays, pitchers of syrup, jam in crystal bowls, slippers stitched with golden thread for the fiancée, and slippers for the entire household fashioned according to the status of each.

The bride-to-be responded with chibouks inlaid with pearls, money and watch cases, an ablution set, towels embroidered with gold, and a silk shirt.

Middle-class people presented more or less the same things but of lesser value, while men from the lower classes gave slippers to the bride-to-be and her mother, and finely ground coffee and sugar to the rest of the family.

HENNA NIGHT

One of the most quaint and enjoyable aspects of the wedding preparations was the henna night, which occurred on the evening before the wedding. Women spent the day at the hamam, bathing, grooming, and luxuriating. At night, they gathered together in the same house and ceremoniously decorated the bride’s hands, feet, and face with henna, then took turns applying it to one another.

At the time of my childhood, henna nights had come to be considered a rural custom and were never practiced in the cities. But I do remember visiting relatives in the country and, for the first time, having both my hands covered with a gray-green paste that smelled like horse manure and that kept getting colder as the evening wore on. Then, my hands were wrapped in cloth like twin mummies. I spent a restless night not being able to move my fingers, yet so curious of the outcome that I would not dream of taking the bandages off. The next morning, one of the women carefully unwrapped my hands and washed off the hardened mud. Underneath, my fingers were bright orange. When I returned to the city, other children made fun of me. The henna did not come off for weeks, no matter how well I washed and scrubbed my hands.

In the recent years, henna nights have become a sort of trendy ritual among the more secular and Westernized brides-to-be, as a way of embracing an old tradition but also enjoying female company, not unlike a bridal shower.

WEDDINGS

The bride and groom did not meet prior to the wedding. In his novel The Disenchanted, Pierre Loti dramatizes the unfairness of this situation: “During this last supreme day, still her own, she wanted to prepare herself as if for death, sort her papers, and a thousand little treasures, and, above all, burn things, burn them for fear of the unknown man who in a few hours would be her master. There was no haven of refuge for her distressful soul, and her terror and revolt increased as the day went on.… All these treasures, all the little secrets of beautiful young women, their suppressed indignation, their vain laments—all turned to ashes, piled up and mingled in a copper brazier, the only Oriental object in the room.”

The wedding ceremony began with the arrival of the bride at the groom’s house, heavily veiled, often wearing a red wedding gown and an ornate tiara. She came through a silk tunnel stretched from the carriage to the front door. She was not allowed to look to the right or left but had to keep her head straight while an older woman relative, usually an aunt, led her to the bridal throne set on a dais. As she sat down, the women guests started trilling, and a drumbeat began. The groom then entered, lifted the veil, and saw his bride’s face for the first time. It was a critical moment. He had the right to reject her if what he saw did not appeal to him. By throwing a handful of coins at the spectators, all women, he expressed his satisfaction and acceptance. The women made a wild dash for the money, squealing and elbowing each other. Many of these heavily veiled women were present at every wedding, and there were rumors about men shrouding themselves in women’s guise just to catch a glimpse of the bride’s face. Next the groom took the bride’s hand, and together they went out of the room. Soon afterward, the groom left the house, not to see the bride again for the rest of the day. After his departure, a feast began—lasting the entire day; in wealthier households, sometimes several days. “It lasted forty days and forty nights” was the catchphrase that described some of the more opulent weddings.

Later that night the bride was delivered to the groom’s bedroom by her male relatives. She entered the nuptial bed at the foot, lifting the bedcovers in an elaborate ritual. She remembered that even in paradise, a wife’s place was beneath the “soles of her husband’s feet.” And if that night her hymen did not bleed, the groom had the right to get rid of her. Sheets with bloodstains were displayed from the balconies to attest to a bride’s virginity.

This was my grandmother’s world, but it did not seem that remote; and these tales were utterly terrifying. We heard many stories about such wedding nights, when a couple who had no previous contact was thrown together into a most intimate encounter. My grandmother told us how shocked she was when my grandfather removed his turban and, underneath, had no hair. Since all the male members of her family possessed abundant hair, she had never seen or imagined a bald man. Her wedding night was spent in tears and hysteria. But a rooster was sacrificed to save her honor.

HUSBAND-WIFE RELATIONSHIPS

The singular duty of a married woman was to win her husband’s approval and thereby redeem herself in this life and throughout eternity. The Qur’an declares: “The good wife has a chance of eternal happiness only if that is her husband’s will.… The fortunate fair who has given pleasure to her master will have the privilege of appearing before him in paradise. Like the crescent moon, she will preserve all her youth and beauty until the end of time, and her husband will never look older or younger than thirty-one years.”

Rules compounded rules in enforcing the separation that formed the basis of the harem. Husbands and wives maintained a more or less formal relationship. It was a man’s privilege to look freely upon the faces of his wives, but if curiosity should take him any further, his eyes were accursed. Women were not expected to offer companionship in a man’s intellectual life or other interests. They belonged to his private world; they belonged in his harem. Women and men often dined separately. Men were forbidden not only to enter another man’s harem but even to talk to other men about their own wives. It was sacrilegious—or haram—to make any reference to the female gender in public. Even in announcing the birth of a daughter, a man referred to “a veiled one,” “a hidden one,” or “a little stranger.”

One of the slips of parchment that the Archangel Gabriel passed on to Mohammed said: “If your wives do not obey you, chastise them. If one wife does not suffice, take four.” Mohammed himself had fifteen wives, an example that led to legalized abuse of the Qur’an’s four-wife injunction.

According to the Qur’an, a woman’s consent is not necessary for marriage. She can neither object to being one of four wives nor to her husband’s having an unlimited number of odalisques. However, each of the four women must be treated with impartiality: each must have her own apartments, her own servants, and her own jewels.

In Turkey, before early twentieth-century reforms, Islamic law recognized four wives and odalisques, but only the first wife was considered legal under civil law. She was the one married with the ceremony described above and she held more privileges above the other wives.

Although most men confessed to the temptation to have several wives, they found it less troublesome to have just one. An old Turkish proverb says: “A house with four wives, a ship in a storm.” Indeed, women often competed for supremacy in the harems, which disturbed the happiness and peace of the entire household. “The wisest men preferred to enjoy a concubine episodically, or even to repudiate their wives, rather than harbor under the same roof the bitter rivalry of ‘competing’ wives,” according to Nadia Tazi in her book Harems. “And those who did decide to have several legal spouses eluded the troublesome side of harem life by maintaining various separate households in different districts of the city, among which they divided their time.”

Good husbands were diplomatic. They abided by the Qur’an and gave the impression of treating all of their women equally. If one got a new pair of slippers, the others received the same. Often, all the womenfolk lived in one big, rambling house. If jealousy arose among the wives, the husband was obligated to separate them into different households. “And,” according to Gérard de Nerval, “if she does consent to live in the same house as another wife, she has the right to live entirely separately, and she does not take part with the slaves, as people imagine, in any delightful tableau, beneath the eye of the master and the spouse.”

The husbands alternated nights in the bedrooms, spending Friday nights exclusively with their first wives. Indeed, K. Mikes, a Hungarian who lived in Gallipoli and Istanbul for forty-four years, notes in his collection of letters, Turkiye Mektuplari (1944–45), that first wives did have certain sexual rights: “If her husband neglects her for three consecutive Friday nights (this must be night joining Thursday to Friday) the wife can complain to the judge. If he neglects her for even longer, then she can obtain a divorce. This is rare, but Shariat (canonical law) permits it.”

RELATIONSHIPS AMONG WIVES

Most second and third marriages occurred during middle age and tended to be for pleasure—related to a sort of midlife crisis. Men whose wives were barren or had passed the childbearing age often sought young girls. Sometimes the older wife even persuaded her husband to take in a pubescent girl who could fulfill his desires and bear children. Vicariously, she relived her youth and passion through mentoring the young wife, assuming responsibility as the head of the harem and finding additional wives for her husband, if necessary. One Western sojourner in Turkey found it difficult to believe that a wife could reconcile herself to such sharing of affection:

The older wife had no children so she herself had chosen a wife for him young enough to be her daughter.… Both women were busy with preparations for the expected baby, to whom the first wife referred as ‘our child’ and she seemed to be as worried about the fate of her rival as she would have been about her daughter. Yet, who knows what sorrow was gnawing at her heart strings, for she loved ‘the master.’ Can one share the object of one’s affections without a pang?

Grace Ellison, Turkey Today (1928)

Yet aging women were obliged to suppress such emotions. If they were no longer desirable or useful, often there was no place for them to go unless they had close relatives willing to take them in. Besides, a divorced woman was not kindly looked upon by society.

When he came in, he kissed his first wife first, then his second, and it seemed to me that there was a difference in his manner to the two, the first being that of a lover, the second that of an older man to a pet child.

Demetra Vaka, Haremlik (1909)

We used to have a maid, a tiny, withered, birdlike creature with a beak nose and missing teeth. I think her name was Sherife Hanum. She was married to an attendant of my father’s, and they had no children. I remember the old woman eyeing a laundry girl whom she later chose to be her kuma (literally, “rival”). The kuma bore her husband three children the old woman called her own, and she worked her tired muscles to support her husband’s wife and children. Women’s emancipation in Turkey had officially abolished such situations, but the attitudes of the people had not caught up with this change.

Still, it was humiliating for many women to live through this kind of ordeal. A great deal of anguish occupied women’s hearts; they felt inadequate to please their husbands and fulfill their religious obligations. The following description of a home with two wives, written around 1909, comes from the able pen of the Turkish author Halide Edip:

When a woman suffers because of her husband’s secret love affairs, the pain may be strong, but its quality is different. When a second wife enters her home and usurps half her power, she is a public martyr and considers herself an object of curiosity and pity. However humiliating this may be, the position gives a woman unquestioned prominence and isolation.

Whatever theories people may regard ideal as family constructions, there remains one irrefutable fact about the human heart, to whichever sex it may belong—it is almost organic in us to suffer when we have to share the object of our love, sexual or otherwise. As many degrees and forms of jealousy exist as human affection. But suppose time and conditioning were able to tone down this elemental feeling, the family problem still will not be solved. The nature and consequences of the suffering of a wife who in the same house shares a husband lawfully with a second wife and equal partner, differ both in kind and degree from that of a woman who shares him with a temporary lover. In the former case, the suffering extends to children, servants and relations whose interests are themselves more or less antagonistic, and who are living in a destructive atmosphere of distrust and struggle for supremacy.

In my own childhood polygamy and its results produced a very ugly and distressing impression. The constant tension in our home made every simple family ceremony seem like physical pain, and the consequences of it hardly ever left me. The rooms of the wives were opposite each other and my father visited them in turn. When it was Teize’s turn everyone in the house showed a tender sympathy to Abla, while when it was her turn no one heeded the obvious grief of Teize. She would leave the table with eyes full of tears, and one could be sure of finding her in her room crying or fainting. I remember very clearly my feeling of intense bitterness against polygamy. It was a curse, a poison which our unhappy household could not get out of the system.

I was so full of Teize’s suffering and so constantly haunted by her thin, pale face, tear stained and distorted with grief even when she was kneeling on her prayer rug, that this vision had become a barrier between me and Abla. Yet one emotion of sudden pity for Abla was just as natural to my heart as the other.

Huda Sharaawi, Egypt’s revered feminist, was betrothed to her cousin in 1891, at the tender age of thirteen. The cousin was old enough to be her father and already had a slave concubine and children by her. Huda’s mother made the groom sign an affidavit attesting that he would not take any more wives. Sensitive Huda was crushed by this marriage—from which, to her great relief, she was delivered after eighteen months, when her husband made another woman pregnant, thereby annulling the marriage.

Man’s pleasure is like the noonday halt under the shady tree; it must not—it cannot—be prolonged.

Arab proverb

Huda’s friend Attiya Saqqaf records in her memoirs (1879–1924) several breaches of confidence, when her husband, who often traveled, acquired more wives on the road—a common practice among “traveling men”: “During the annual haj season he had worked on the pilgrim ships bound for Arabia. He would marry a woman aboard ship and divorce her upon arrival. His marriages were so numerous he couldn’t count them nor did he know the number of children he had. Meanwhile, I found him chasing after servant girls in the house.”

Sometimes men concealed from their first wife the fact that elsewhere they had another wife—sometimes even other children. When such a secret was discovered, the wife usually attempted to return to her father’s house. In At the Drop of a Veil, Marianne Alireza tells how her brother-in-law kept another wife in Egypt, and when his first wife found out, she tried escaping to her family home—but was not able to get a driver to take her. For however disturbed a wife might be by the discovery of a secret wife, custom compelled her ultimately to take the revelation in stride.

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Odalisque, 1870, Oil on canvas, 241⁄4 × 481⁄4 in., National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Chester Dale Collection

Paul Bowles, in his haunting novel The Sheltering Sky, describes a young American woman whose husband dies in the desert while they are traveling. A caravan picks her up, and one of the leaders claims her as his own. He takes her back to his house, disguised as a boy so that his three wives will not feel threatened. He keeps “the boy” locked up in a tiny room he enters every afternoon to make wild love to her: “It would occur to her when he left and she lay alone in the evening, remembering the intensity and insistence of his ardor, that the three wives must certainly be suffering considerable neglect.… What she did not guess was that the three wives were not being neglected at all, and that even if such had been the case, and they believed a boy to be the cause of it, it never would occur to them to be jealous of him.”

Harems housed extended families: wives, mothers, unmarried sisters and daughters, sometimes other distant women relatives who needed shelter. The wives, never knowing when the husband might visit the harem, kept themselves decked out in anticipation at all times. They always did their best to put on a cheerful, happy exterior and to conceal their anguish or displeasure at all costs.

One of my aunts had a maid named Rabia. When Rabia was sixteen, she married a man who already had a wife. My parents talked about this disapprovingly. A few months later, Rabia returned. She had run away, she said, because the first wife and the mother-in-law had been torturing her. They made her slave away all day long, cleaning, cooking, and washing the laundry. She’d work so hard, she could not stay awake until the time her husband returned. But those awful women told her husband that she was lazy, stubborn, and good for nothing. All she did was sit around all day while they exhausted themselves.

Elizabeth Warnock Fernea, in Guests of the Sheik, describes a similar situation in an Iraqi village: “ ‘They hate me, they hide the sugar and steal my cigarettes, they pour salt in the food I prepare for my husband, they gossip about me to the neighbors and they tell my husband I am mean and will not help with the housework. They want nothing except to get me out. How can I make friends with them?’ She broke down and sobbed loudly in her abayah [long veil].”

SUPERSTITION AND CHARMS

Women resorted to numerous superstitious practices to compensate for their situation. They dissipated their jewels and other worldly goods among the gypsies, herbalists, and jadis (witches), buying concoctions to make their rivals barren and to prevent their husbands from desiring other women. Gypsies read palms, coffee grounds, or beads. They gave talismans to women to preserve their youth, or decoctions to make a love philter, or a fetish to make cruel husbands kind, or evil-eye charms to protect children. It was considered a bad omen to say good things about a child’s health and growth because that was tantamount to inviting the evil eye, so women looked at each other’s children and said, “Poor thing.”

A tinker lived near my grandparents in Karshiyaka. His wife, Dudu, was an enormous woman with a bad temper. She especially disliked children. She threw stones whenever she saw us picking cones for pine nuts, even though the trees did not belong to her. Everyone gossiped about how the poor tinker, a mild-mannered man, should find another wife—especially since Dudu could not even bear him children. One summer, the rumor was that the tinker indeed had eyes for another woman, a young widow with a little boy. Everyone thought this would be a good match; it would not only offer him a pleasant woman who could bear children, but also provide a home for her orphaned son.

We did not see Dudu for days, even when we picked pinecones behind her house. Rumor said she had gone to see a witch woman.

Some days later, as my friend Esin and I were playing in a field, we saw Dudu walking at a very fast pace down the road, carrying a live rooster upside down, which kept pecking at her hands and flapping its wings. When she went into her house, we hid behind the fence to watch her. She came back out, carrying the rooster, a basin of water, and a kitchen knife. She immersed the bird’s neck in the water and struck the jugular. The bird blissfully bled to death in the water.

A few days later, the young widow’s son was diagnosed with meningitis. He did not live very long. It was the rooster that did it, they said. It was charmed. The widow left town, and the poor tinker was stuck with nasty, shrewd Dudu.

UPKEEP

More wives were brought in as the maintenance of a household became more complex and demanded more attention. There were children to take care of, servants to supervise, and guests to entertain. New blood was needed to perform some of these tasks. So the harems grew. Nerval compares them to a sort of convent: “When there are many women, which only happens in the case of people of position, the harem is a kind of convent governed by rigid rule. Its main occupation is bringing up children and the direction of the slaves in the household work. A visit from the husband is a ceremonial affair, as is that of close relatives, and as he does not take his meals with his wives, all he can do to pass the time is to smoke his nargileh seriously, and drink coffee or sherbets. It is the proper thing for him to give notice of his coming in advance.”

“They do not, as the common description of harem life leads us to believe,” comments historian C. B. Kluzinger (1878), “recline the live-long day on a soft divan enjoying dolce far niente, adorned with gold and jewels, smoking and supporting upon the yielding pillow those arms that indolence makes so plump, while eunuchs and female slaves stand before them watching their every sign, and anxious to spare them the slightest movement.”

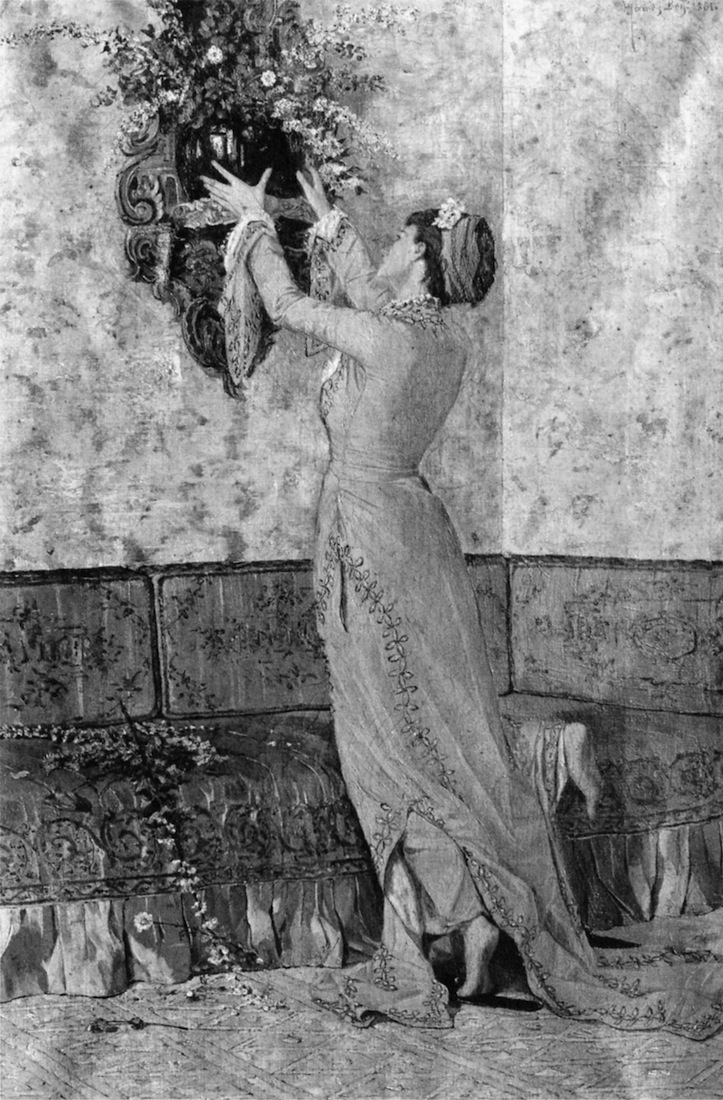

Osman Hamdi, Girl Arranging Flowers in a Vase, 1881, Oil on canvas, 57 × 38 in., Istanbul Resim ve Heykel Müzesi (Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum). Osman Hamdi was a Turkish painter who studied in Paris under Gérôme.

Besides the wives, the men had the servant women to reckon with. Odalisques (besleme) had no rights at all until they were married, and even marriage freed them only from being outright slaves; they were now the property of their husbands. My great uncle Rüstem had a besleme, a beautiful woman named Pakize, who served him as his wife until he died. Even though, for all practical purposes, she was the wife, the rest of the women in the family, the “legitimates,” were prejudiced against her and looked down on her as a servant.

In large households, where several male family members shared the selâmlik (the men’s section), the odalisques had a more difficult plight. A carnival troupe who used to perform in Izmir during my childhood had a popular song, which they sang to the tune of “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep,” about a slave girl who became pregnant and was called before the family to tell who, among the masters of the big household, was the father. “Tell us who, tell us who?” sang a chorus of men. “I cannot, I cannot, for I don’t know who,” responded the girl. “Tell us who, tell us who, don’t be afraid to.” After a long pause, the girl coquettishly began singing, “Well, there was old master so and so and the young one, too. And the older brother of the master, and the brother of the mistress …” and so on.

All the slave women in the house were at the disposal of the master. The children born of these slaves were considered legitimate, and the woman rose to the rank of wife. Leyla Saz summarizes the precarious position of the odalisques:

The odalisques who were favorites of the master of the household or who had borne children, had one or two rooms each. However, if their master became tired of them, two or three of them were cluttered into one room, their status even lower than a black slave, who could at least be in the master’s presence. These unfortunates were terrified to meet the heartless man, and spent their lives fawning upon his mistress, trying to quench their pangs of jealousy.

Even worse, it was quite simple to get rid of unwanted wives or odalisques with perfect impunity; for no man, not even a police inspector, could enter another’s harem.

JEWELRY

A woman’s jewelry was considered her only insurance against disaster; legal action could be taken against any man who attempted to seize a woman’s gold or gems.

When my grandmother was widowed, she sold all her jewelry, little by little, to put her sons through school. Sometimes with tears in her eyes she would describe an emerald necklace with thousands of tiny baby pearls, which she had inherited from her own grandmother. “But it’s all right, it’s all right, because it bought this house.” She was referring to the house in the Karatash district of Izmir, where I was born. To a child’s mind, used to judging the value of things by their size, it was incomprehensible that a necklace could actually buy an entire house.

The windows of the women’s apartments either opened onto an inner courtyard or were closely barred with latticework, concealing them from the outside world. These artfully designed, intricately woven lattices are undoubtedly some of the most beautiful elements of Islamic architecture. But what made them most compelling were the silhouettes of the shadows behind them.

“Almost all the rooms are small,” according to Edmondo de Amicis’s Constantinople (1896), “the floors covered with Chinese matting or rugs, screens painted with flowers and fruits, a wide divan runs all around the wall, pots of flowers stand on the window sills, there is a copper brazier in the center, and lattices cover the windows. In the Selâmlik, a man works, eats, receives his friends, takes his siesta, and sometimes sleeps at night. The wives are never allowed to enter. Although it is separated from the harem simply by a narrow corridor, it is like two separate houses. Often different servants serve the two sections and there are separate kitchens.”

A woman plays ud in a real Turkish harem. At the turn of the century the harems were decorated in Oriental style mixed with European Art Nouveau.

Enclosed balconies with latticed windows allowed women to observe what was going on outside without being seen. Courtyards, roof gazebos, and gardens gave them a chance for a breath of fresh air, though these places were still considered haram. Roof terraces were favorite places to watch the boats go by, take a siesta, and enjoy refreshments.

Women in harems frequently visited each other, bringing gossip, unusual recipes, and embroideries, and showing off their new clothes and jewelry. Often these visits were unannounced. If the husband found slippers at the entrance to the harem, it was an indication that the wives were entertaining guests and he was not supposed to go in. Some guests stayed on for several days.

In our house in Istanbul, two very old spinsters lived on the first floor. They were sisters, neither of whom had married because their father had wanted to keep them for himself. Their youth had been spent behind harem lattices, which they still imposed upon themselves in order to perpetuate existence in a murky shadow world. They had jalousie shades put up to bar themselves from the vision of those who passed by and to watch the world parade before them without being seen. Whenever I walked down the stairs to go out the front door we shared, I could hear their footsteps padding to the windows, where they would situate themselves at a vantage behind the shutters from which to observe me. They seemed to experience vicarious pleasure in ogling the innocence of youth. They also seemed to be seeking any sign of scandal they could turn to gossip.

A sheik tells Gérard de Nerval:

The arrangement of a harem is the same.… There are always a number of little rooms surrounding the large halls. There are divans everywhere, and the only furniture consists of tortoiseshell tables. Little arches cut into the wainscoting hold narghiles, vases of flowers, and coffee cups.

The only thing which these harems, even the most princely of them, seem to lack is a bed.

“Where do they sleep, these women and their slaves?” I asked the sheik.

“On the divans.”

“But they have no coverlets?”

“They sleep fully dressed. But there are woollen or silken covers for the wintertime.”

“That is all very well, but where is the husband’s place?”

“Oh, the husband sleeps in his room and the women in theirs, and the odalisques on the divans in the larger rooms. If the divans and the cushions don’t make a comfortable bed, mattresses are put down in the middle of the room, and they sleep there.”

“Fully dressed?”

“Always, but only in the most simple of clothes, trousers, vest and robe. The law forbids men as well as women to uncover themselves before the other sex, anywhere below the neck.”

“I can understand,” I said, “that the husband does not greatly care to pass the night in a room filled with women fully dressed, and that he is ready enough to sleep in his own; but if he takes two or three of these ladies with him …”

“Two or three!” cried the sheik indignantly. “What dogs do you imagine would act in such a way? God alive! Is there a woman in the world, even an infidel, who would consent to share her honorable couch with another? Is that how they behave in Europe?”

“In Europe,” I replied, “certainly not; but the Christians have only one wife, and they imagine that the Turks, who have several, live with them as with one only.”

“If there were Mussulmans so depraved as to act as the Christians imagine, their lawful wives would immediately demand a divorce, and even their slaves would have the right to leave them.”

BUNDLE WOMEN

European merchants sometimes married local Christian or Jewish women so that they could infiltrate the harems with their merchandise. Marianne Alireza describes such an encounter: “I guessed that she was some poor soul who had come for a handout and that the bundles contained our contribution. But she was a lady peddler and the bundles contained her wares. She was Circassian and had come many years before to perform the pilgrimage and like so many others decided to stay. Her goods were mostly notions and cheap toys, some bangles and trinkets, and a buksha with cheap gaudy fabrics and some lace. From a sheer need for some kind of excitement, women of the harem purchased almost everything.”

Bundle women, bohcaci, often appeared at our doorstep, and I cannot forget my excitement and wonder as I watched their goods slip out of the bundles. They were strange things, bedspreads of garish colors and tacky baroque designs from Damascus, diaphanous nightgowns made of Shile fabric, and a profusion of lace and ribbons. My grandmother and my mother always bought something for my hope chest, which, I must have known deep down, was more for them than for me. Over the years, the hope chest dwindled, the bedspreads and those ethereal nightgowns given away as gifts to women relatives who got married or people who had been good to the family.

A harem lady visited by a bundle woman and a gypsy fortune-teller: precious contact with the outside world. Collection of the author

“Alev’s hope chest” was still in my parents’ house when I visited them a few years ago. Inside, there were just a very few things: some doilies, scarves, and the Damascus bedspread I personally remembered buying from a bundle woman long ago. My mother insisted that I take it back with me, and I was caught between wanting to please her and being appalled by the bright orange, yellow, and green florals. It would never do. But I took it with me anyway, slightly embarrassed when Turkish customs searched my suitcase and this particular artifact was questioned. Was it an antique? Did I have special permission from the government to export it? I told them it was a gift from the family, and that it had been in my family ever since I could remember. Why was I going through such an ordeal for something I was embarrassed by and would probably give to the Goodwill as soon as I returned home? (It turned out that a friend fell in love with this ungodly piece of “art,” and it now adorns her bedroom in San Francisco.)

Again, during the same visit, I was sitting in a café in the Prince Islands, surrounded by a bevy of Arab harem women, waiting for the ferry, when a Circassian woman came through the crowd, carrying two suitcases, which in today’s world had replaced the old “bundle.” She spilled the contents and could not escape my own curious eyes as she held them up for us to see. I was disappointed that the exotics I remembered were gone; no more strange kaftans, Damask silks, Egyptian cottons. Now the bundle woman was selling mainly crochet and knit items made from synthetic yarns, which are ever so popular today in the Middle East, and there were some cheap Turkish towels and burnooses (bathrobes) from the tourist loom. The romance of the bundle was over.

DEATH

Moslems believe that death is a departure from the life of this world, but not the end of a person’s existence. Rather, eternal life is to come, and they pray for God’s mercy for the departed, in hopes that they may find peace and happiness in the hereafter.

The dead were washed, shrouded, and buried as soon as possible. Coffins were not used, because it was believed that the body must be returned directly to the earth. On the evening of the funeral, they read the Qur’an with neighbors and friends, to pray for the soul of the deceased, and a special halvah made of farina, cinnamon, and nuts—which is delicious—was served. There was no group service over the body, but for forty days the family was expected to open their door to the public, who would visit and pay condolences. Coffee, tea, and other refreshments were served to the visitors, and fresh waves of grief had to be shared with each arrival. On the fortieth and fifty-second days following the death and also on the anniversary of the funeral, a professional chanter intoned verses from the Qur’an, and the women covered their heads, prayed, and sent the spirit of the departed away. The Mevlits (prayers of mourning) for women mostly took place at the home of the deceased in the afternoons and were followed by a big meal.

The tombstones that still adorn the old Ottoman cities indicate whether the deceased was a man or a woman: women’s headstones had flower designs, and men’s were shaped like turbans.

Every Friday, which is the day of religious observance for the believer, a long line of veiled women accompanied by children wends its way along the cemetery road, like a row of reeds along a river. The women love the cemetery: for them it means temporary reprieve from the generally cloistered condition imposed on them by the laws of Islam; it represents a destination for an outing; and the tears they shed for the departed provide relief for their worries.

Etienne Dinet, Tableaux de la vie arabe (1908)