It is a world in which all the senses feast riotously upon sights and sounds and perfumes; upon fruit and flowers and jewels, upon wines and sweets, and upon yielding flesh, both male and female, whose beauty is incomparable. It is a world of heroic, amorous encounters.… Romance lurks behind every shuttered window; every veiled glance begets an intrigue; and in every servant’s hand nestles a scented note granting a speedy rendezvous.… It’s a world in which no aspiration is so mad as to be unrealizable, and no day proof of what the next day may be. A world in which apes may rival men, and a butcher may win the hand of a king’s daughter; a world in which palaces are made of diamonds, and thrones cut from single rubies. It’s a world in which all the distressingly ineluctable rules of daily living are gloriously suspended; from which individual responsibility is delightfully absent. It is the world of a legendary Damascus, a legendary Cairo, and a legendary Constantinpole.… In short, it is the world of eternal fairy-tale—and there is no resisting its enchantment.”

—B. R. Redman, Introduction to The Arabian Nights Entertainments (1932)

In German there is a beautiful word for the East, Morgenland, the land of the morning. The East, or the Orient, is where the sun comes from, and it encompasses Asia Minor, Persia, Egypt, Arabia, and India. The Orientalist painter David Roberts remarked that the light of Egypt “washed out colors, banishing vibrant tints to the shadows.”

Orientalism is the Western version of the Orient, created by the Western imagination and expressed by Western art forms. It is the East of fantasy, of dreams. In fact, most Orientalist artists merely dreamed; they created their visions of the Orient without ever leaving their home country. A few actually traveled to the East, daring to temper fantasy with fact. But even these adventurers could not resist the temptation to inflate their visions with a romantic breath, as Julia Pardoe observed as early as 1839: “The European mind has become so imbued with ideas of Oriental mysteriousness, mysticism and magnificence, and it has been so long accustomed to pillow its faith on the marvels and metaphors of tourists, that it is to be doubted whether it will willingly cast off its old associations and suffer itself to be undeceived.”

During the early eighteenth century, the floodgate of romance was opened—not as a result of politics or commerce, but by a book of fairy tales. In 1704, a French scholar named Antoine Galland translated Alf Laila wa Laila, the One Thousand and One Nights, or Arabian Nights. These tales were set in the kingdom of the great caliph Harun al Rashid, inhabited by mysterious sultans, eunuchs, and slave women, as well as genies, giants, and pegasi (flying horses). When Sultan Shahriar discovers that his wife has been unfaithful to him, he executes her, declaring that all women are as evil as the sultana and the fewer women the world contained, the better. Every evening, he marries a new wife just to have her strangled the following morning. It is the job of the grand vizier to provide the sultan with these unfortunate girls from a terrorized kingdom. One day, the grand vizier’s daughter, Scheherazade, who clearly has a scheme, persuades her father to take her to the sultan as his new wife:

When the usual hour arrived, the Grand Vizier accompanied Scheherazade to the palace and left her alone with the Sultan, who bade her raise her veil and was amazed at her beauty. But seeing her eyes full of tears, he asked what was the matter.

“Sire,” replied Scheherazade, “I have a sister who loves me tenderly as I love her. Grant me the favor of allowing her to sleep this night in the same room, as it is the last we shall be together.”

The Sultan consented to this petition and Dinarzade was sent for. An hour before the daybreak Dinarzade awoke, and exclaimed as she had promised:

“My dear sister, if you are not asleep, tell me I pray you, before the sun rises, one of your charming stories. It is the last time I shall have the pleasure of hearing you.”

Scheherazade did not answer, but turned to the Sultan:

“Will your highness permit me to do as my sister asks?” said she.

“Willingly,” he answered.

So Scheherazade began.…

Sultan Shahriar is so captivated by Scheherazade’s tale that he spares her life on condition that she will tell him more. Thus, the beautiful sultana fills one thousand nights and a night with romance. Scheherazade spins one captivating story after another, one night after another, redeeming her life. The sultan’s attitude toward women is transformed, the kingdom is healed, and everyone lives happily ever after.

Edmund Dulac, Scheherazade. Original watercolor for frontispiece of The Thousand and One Nights, 1907, Watercolor on paper, 135⁄8 × 65⁄8 in., Jo Ann Reisler, Ltd., Vienna, Virginia

As folktales, these stories were singular to begin with, but, in time, evolved into a Chinese-box pattern of tales within tales within tales. They metamorphosed as they traveled from one kingdom to another, but never lost the element of dangerous exoticism, implications of hidden mysteries, and erotic nuances. Their plots are utterly convoluted mirrors within mirrors. One of Horace Walpole’s celebrated letters (to Mary Berry, August 30, 1789) suggests the appeal the tales held even for an eighteenth-century man of letters: “I do not think the Sultaness’s narratives very natural or very probable, but there is wildness in them that captivates.”

A man enjoying himself with more than one woman was a compelling fantasy, and Galland was a gifted storyteller. The tales themselves being very seductive, they quickly became a sensational form of popular adult entertainment in Europe. They also partook of what nowadays we might call the “expansion of consciousness.” Bored with the already established contexts, many writers and artists found refuge in these Eastern labyrinths for their own tales, yet always sustaining elements from the original.

WIND FROM THE EAST

One Thousand and One Nights not only introduced to Europe a new art of storytelling beyond the linear narrative but also provided a theatrical arena for a flamboyant society. Eighteenth-century men and women loved to dress up in costumes and pretend, and with The Arabian Nights, their repertory grew, giving them a new set of exotic characters to impersonate. Prosperous Victorians, who were normally obliged to wear dark suits, wanted to put on flowing robes in all manner of colors and fashions.

In Paris, then other European capitals, Turqueries became the rage, influencing everything, from theater, opera, painting, and romantic literature to costume and interior design. Harem pants, satin slippers, and turbans became faddish items of high fashion. Nobility dressed like pashas, odalisques, sultanas; they posed in Turkish costumes for portraits by the popular painters of the period. Many dabbled in imitations of Eastern poetry. Women indulged in telling stories à la Scheherazade.

Orientalia—nargilehs, low divans, and jeweled scimitars—gradually insinuated its way out of the chic houses and into more prosaic dwellings throughout Europe. The concept of keyf (fulfillment in sweet nothingness)—dolce far niente—spread as a popular philosophy among Europeans, who had begun to develop a penchant for quiet euphoria. Smoking opium and hashish became an aesthetic and spiritual pursuit used to expand the creative romantic mind. Poets and writers like Coleridge and De Quincey indulged in opiates to induce prophetic visions, giving voice to such sensuous masterpieces as “Kubla Khan,” which Coleridge wrote while under the influence. Gérard de Nerval, Eugène Fromentin, Théophile Gautier, and Charles Baudelaire gathered in the Hôtel Pimodan, where members of the Club des Haschichins held secret smoking salons.

France was setting a trend for adapting Oriental tales into social satire. Voltaire wrote Zadig; Montesquieu, Persian Letters; and Racine, Bejazit, dramatizing a terrible struggle between two sultanas, modeled on the lives of Kösem and Turhan, and presenting in the process a metaphor for the repression of desire in eighteenth-century Western society. A public who saw in it their own secret passions come to life enthusiastically received the play.

Simultaneously, musical harems filled the palaces of Versailles and the Hapsburg court. Janissary music or marches had been popular in Europe since the siege of Vienna. Beethoven’s “Turkish March,” Haydn’s Military Symphony, and other Turkish marches followed. During the late eighteenth century, Mozart introduced visions of a salubrious Orient in The Magic Flute, whereas Abduction from the Seraglio had been smashingly exuberant in its exoticism and presentation of virtuous Oriental humanity—music and dance coming to the rescue of a beautiful odalisque in the Seraglio. Turkish music also appeared in works of Rameau, Rossini, and Spohr, as well as two operas by Gluck. Compositions such as Boieldieu’s Caliph of Baghdad, “Mameluke’s Waltz,” and ultimately Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Scheherazade continued the trend. Even Irving Berlin composed a song called “In My Harem.”

“It was like a scene out of the Arabian Nights” became the cliché phrase used to describe any amazing, rich, or peculiar experience. Out of lassitude or otherwise, the well of Western culture seemed to be running dry, which made the pursuit of the exotic irresistible. Tourism to the East boomed. The Orient beckoned to many Westerners. As Rudyard Kipling said: “Once you have heard the call of the East, you will never hear anything else.”

“The world here Romantic. Women differ from ours. Unaffected. Lazy life,” wrote Lady Mary Wortley Montagu to Alexander Pope from Istanbul. Between 1716 and 1718, she lived in Turkey as the wife of the British ambassador, Edward Wortley Montagu. One of the first great romantic women travelers to the Orient, she was full of self-discovery, incessantly writing her impressions and carrying on a fastidious correspondence with her European friends. Her Turkish Embassy Letters are perhaps the most authentic and direct experience of the East any gavur (infidel—also, foreigner) has articulated.

Lady Mary radiated all the eighteenth-century contradictions that Orientalism revealed. She was caught in the creative tension between passion and reason, love of romance and pragmatism, a spirit of adventure and a rage for order. She surrendered to the seduction of the East while maintaining her identity as a young English noblewoman. Her year in Constantinople where “luxury was the steward and treasure inexhaustible,” was exceptional. For the first time, we have a Western woman’s direct experience of the Ottoman women’s world. Her descriptions of women are beautiful, lush, and opulent: “On a sofa rais’d 3 steps and cover’d with fine Persian carpets sat the Kahya’s lady, leaning on cushions of white satin embroider’d, and at her feet sat 2 young Girls, the eldest about 12 years old, lovely as angels, dress’d perfectly rich and almost cover’d with Jewells.… I must own that I never saw any thing so gloriously Beautifull,” she wrote to her sister, Lady Mar, on April 18, 1717.

She was the perfect voyeur; the sensuality of such scenes did not elude her. At the same time, she maintained her own culture’s sense of propriety. For example, when she was asked to join a few ladies in the baths and realized that they were all “stark naked,” she was able to demur through convenient dissembling: “I was at last forced to open my shirt and show them my stays, which satisfied them very well, for I saw they believed that I was locked up in that machine, and that it was not in my power to open it, which contrivance they attributed to my husband.”

She carried on an intimate correspondence with the poet Alexander Pope, in which they dialogued on Oriental culture. Lady Mary actually experienced this world; Pope fantasized vicariously: “I heard the pretty name of Odalisque,” Pope wrote to Lady Mary on September 1, 1718. Like other men of this period, he went as far as to put in an order for a Circassian slave woman: “This is really what I wish from my soul, tho’ it would ruin the best project I ever lay’d, that of obtaining, thro’ your means, my fair Circassian Slave.”

Lady Mary did not import a slave for the hunchbacked poet, but she did bring back other turqueries to England, including harem attire, which soon became a fashion statement. She inoculated her children with smallpox vaccine as she had seen done in Turkey, some seventy years before Dr. Edward Jenner “introduced” the vaccination to England. Voltaire, who was familiar with Lady Mary’s practices, attributed the origins of this vaccine to the Circassian women in harems, who were keen to prevent smallpox in order to preserve their beauty from pockmarks.

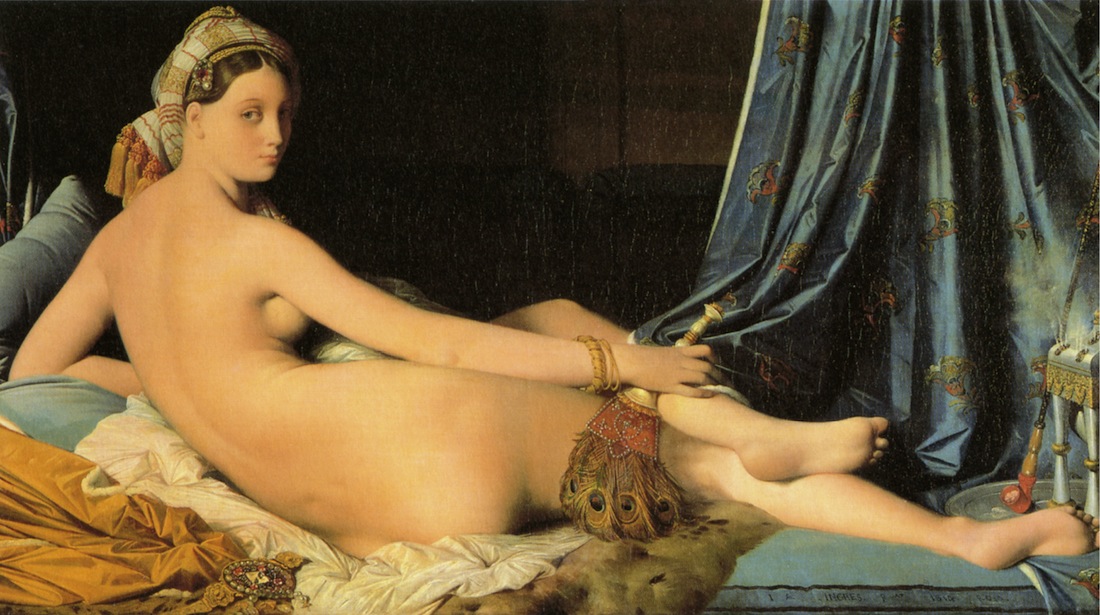

In the visual arts, harem scenes had, by the nineteenth century, become a convenient excuse for painting titillating nudes. The odalisque, who represented simply a female servant to the Turks, had become the symbol of exotic and erotic splendor to the Europeans. Ingres’s Grande Odalisque (1814) was utterly unoriental in its cool classicism, depicting an elongated, reclining woman, resembling an alabaster urn. A vessel herself, impenetrable. The artist had transformed a nude woman into a manneristic phantasm merely by adding a turban, a fan, and a nargileh. Paris was glutted with Orientalist paintings, the success of which finally led to the establishment of the Salon des Peintres Orientalistes Français in 1893.

JOURNEY TO THE ORIENT

For most nineteenth-century Westerners, everyday realism was too vulgar to be presented as art. In search of suitable subjects, then, many artists traveled to the East, which had remained virtually unchanged since biblical times. The gradual improvement in transportation and better accommodations made the lands of the East increasingly accessible, and by 1868 Thomas Cook had established tours up the Nile and into the Holy Land. The Suez Canal was opened in 1869, and Cairo received a face-lift, complete with luxury hotels and an opera house, which was opened with Verdi’s Aida. By the 1890s, Egypt had become as fashionable a resort as the Riviera, and in 1893 the Orient Express was carrying glamorous passengers between Paris and Constantinople. Painters Melling and Preziosi followed Liotard and Vanmour to Turkey; John Frederick Lewis, Flaubert, Nerval, Gérôme, and Florence Nightingale journeyed to Egypt; Delacroix to Algeria. Although he would never set foot inside a harem, Eugène Delacroix claimed that a man actually allowed him to peek into one. The result was the exquisite Women of Algiers in Their Room, which he painted in 1834. Ten years later he painted another version of the same scene.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, Oil on canvas, 353⁄4 × 633⁄4 in., Musée du Louvre, Paris

JOHN FREDERICK LEWIS

John Frederick Lewis, a talented dandy from London, made a leisurely four-year tour ending in Constantinople, before moving to Cairo, where he settled for a decade. From 1841 until 1851, he lived the life of a rich Turk, affecting native dress and customs of Cairo. Wearing a turban, a glittering scimitar dangling at his side, he rode through the streets on a gray horse. He adopted the posture of a languid lotus eater and lived what William Makepeace Thackeray described as the “dreamy, hazy, lazy, tobaccofied life” of a wealthy Moslem. Lewis made real the Orientalist’s ultimate dream of changing costume and address, and assuming a separate identity. At first, it was a romantic game, but gradually it consumed him, prompting graceful canvases. Lewis avoided the tourist attractions most other Europeans sought and mingled instead with the people of Cairo. His greatest pleasure was to spend long periods in the desert hinterland in his encampment under the starlit Egyptian nights. He worked restlessly, painting harems, bazaars, and street scenes as they were, without moralizing.

Curator Charles Newton observed of Lewis’s watercolor Life in the Hareem Cairo that “the exquisite finish, the ambiguity of the narrative and the intimate nature of these interiors made Lewis the British equivalent of Vermeer and not just a decorative painter of Orientalist themes.” It was anecdotal instead of erotic, with a domestic serenity that is indeed reminiscent of Vermeer’s interior scenes.

In his Notes from a Journey (1844), Thackeray describes visiting Lewis in Cairo. Thackeray was escorted into the salon of a Mameluke-style mansion, with a carved, gilt ceiling, decorated with arabesques and prime samples of calligraphy. From the courtyard, he noticed two enormous, flirtatious black eyes peering through the lattices. Lewis pretended it was only the cook, but Thackeray was convinced she had to be la belle esclave. After all, wasn’t every man entitled to at least one odalisque?

THE ROMANTICS

Lord Byron considered himself a great Oriental traveler, but, for him, the Orient was limited to Constantinople, the Bosphorus, and the Hellespont. The romantic works of Byron, Coleridge, Victor Hugo, Gustave Flaubert, and Théophile Gautier stood in exotic contrast to the grimy rationality of the industrial revolution sweeping Europe. Victor Hugo’s Les Orientales, in its passionate depiction of captive souls, inspired canvases; Montesquieu’s Persian Letters prompted Lecomte du Nouy’s sensuous painting Koshru’s Dream.

Gérard de Nerval traveled through the Orient carrying two Arabic words, tayeb (assent) and mafish (rejection). In his Voyage en Orient (1843–51), he laid bare the emotions behind his own pursuit of a slave woman named Zetnaybia: “There is something extremely captivating and irresistible in a woman from a faraway country; her costumes and habits are already singular enough to strike you, she speaks an unknown language and has, in short, none of those vulgar shortcomings to which we have become only too accustomed among the women in our own country.”

But after attaining the slave woman, Nerval does not quite know how to integrate her into his life. What should he do with her now? In this wonderful encounter, we come face to face with a clash of cultures and are not certain who is the slave and who the master. Unsuccessful in civilizing Zetnaybia and unable to accept her “primitive” idiosyncracies, he frees her.

In 1849, Gustave Flaubert, with his friend Maxime du Camp, set off for the Orient, which had long haunted his imagination. Like Nerval, Flaubert glorified the seductions of Oriental women. He spent a year in Egypt and kept a diary full of erotic and sensuous detail: “Kuchuk shed her clothing as she danced. Finally she was naked except for a fichu which she held in her hands and behind which she pretended to hide, and at the end she threw down the fichu. That was the Bee.… Finally, after repeating for us the wonderful step she had danced in the afternoon, she sank down breathless on her divan, her body continuing to move slightly in rhythm.” This leads to an incredible night of passion with the alme (dancer) Kuchuk. Flaubert describes his experience in detail candid enough to have made his mistress, Louise Colet, extremely jealous.

Oriental female dancers intrigued even Théophile Gautier:

They stir strange nostalgias, dredge up infinite memories and conjure forth previous existences that come straying back in random array. Moorish dancing consists in perpetual undulations of the body: twisting of the lower back, swaying of the hips, movements of the arms, hands waving handkerchiefs, languid facial expressions, eyelids fluttering, eyes flashing or swooning, nostrils quivering, lips parted, bosoms heaving, necks bent like the throats of love sick doves … all these explicitly betoken the mysterious drama of voluptuousness.

Such scenes fascinated both men and women. On watching the gyrations of a dancer’s breasts, Lady Duff Gordon opined, “They were just like pomegranates and gloriously independent of any support.”

JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME AND THE CAMERA

The primitive technology of the camera and lengthy exposure times, as well as the often hostile resistance of the Moslem people to having their pictures taken, produced a vision of the Orient that was starkly at odds with the lavish one evoked by nineteenth-century writers and painters. The Orient the photographers captured was one of ruins and melancholic landscapes. As Charles Newton observed of a photograph of the fountain of Ahmed III in Constantinople, taken around 1860, the “monochrome image suggests an air of dereliction and decay, even when precisely and rapidly rendering the details of the architecture. There is no colour and life that a painter might suggest, and the street vendors are shown only as part of a scene of poverty.” Occasional portrayals of whirling dervishes and Moroccan harem fantasias apart, what Orientalist artists mostly offered their clientele was a sedate, dignified, and cleaned-up Orient.

When the people did allow themselves to be photographed, it was not in the crowded streets, but more often in a studio with Orientalist props and a fake landscape on the backcloth, or posed as anonymous figures next to an ancient ruin or a pyramid in order to give a sense of scale. The early photographers traveled with heavy and bulky equipment. Francis Frith’s wickerwork darkroom was mistaken by locals for his harem. The developing usually had to be done on the spot. In the heat, collodion was liable to evaporate or bubble over. It was not easy to get distilled water.

Photographic studios such as Bonfils and Son and Sebah had been active in the East since the 1860s. In 1888, Kodak brought out a portable camera any tourist could operate. By the end of the nineteenth century, photography and photographers such as Frith had severely curtailed the growth of Orientalist painting. However, some painters, like Gérôme, who became one of the most influential voices on the nineteenth-century art scene, took advantage of the new invention, using it in the creation of their own paintings. Even before use of the camera became common, the licked finish of the academic painters’ canvases, in which individual brushstrokes were made to disappear, anticipated the texture of photographic images.

In 1854, Gérôme, whose accuracy of detail no less a figure than Théophile Gautier praised, traveled to Turkey and later to Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Sinai, and North Africa. His photographs served as a convenient aide-mémoire for re-creating Oriental scenes back home. The new technology also provided an additional source of income, as photographic studios could sell reproductions of his paintings.

With the judicious use of props, Gérôme was able to re-create scenes with remarkable accuracy, in unsurpassed detail and with daring color schemes. Especially fascinated by the Turkish baths, he often went to men’s hamams with his sketchbooks to capture background material: “Stark naked perched on a stool, my box of paints across my knees, my palette in one hand … I felt slightly grotesque.”

Although Gérôme never did get inside a harem, his paintings can easily be perceived as visual counterparts of Lady Montagu’s or Julia Pardoe’s descriptions of bath scenes and other aspects of harem life. Revealed through a mist of steam, his women are always perfect and otherworldly.

Gérôme’s marriage to the daughter of the influential art dealer Adolphe Goupil helped disseminate reproductions of his work, which became popular throughout the world, bringing harem scenes not only to the wealthy but, it seemed, to every bourgeois household as well.

AMADEO COUNT PREZIOSI

Unlike Gérôme’s oils, Amadeo Preziosi’s watercolors display a quality of immediacy and robust realism similar to Lewis’s work, although, in other respects, they are quite different in style. A Maltese count, Preziosi was born of a privileged family. When his father opposed his art career, he moved to Constantinople, where he lived for almost half a century, and where he died. He married a Greek woman and had four children, whose descendants still live in Turkey. During the last decade of his life, he became the court painter to Sultan Abdülhamid II.

Preziosi was quick to become associated with the European diplomatic community and to develop a reputation within it. From the 1840s to the 1870s, he supplied images of the city’s life for travelers to take home. A connoisseur, Preziosi selected images of extremely colorful and interesting individuals, yet all of his subjects are clearly flesh and blood, not stylized clichés. The portrait of Adile Hanim, for example, shows a real person, somewhat exotic, but still exuding an emotional complexity that anyone can identify with. This approach was a radical attitude toward the East, which traditionally had been represented by one-dimensional harem girls, depicted in conformity with prevailing European notions of beauty.

Preziosi’s Constantinople had the prosaic vitality of the city’s everyday life. Women picnic at the Sweet Waters of Asia, a Nubian slave attends an odalisque who smokes a chibouk and drinks coffee, women finger silk fabrics at the bazaar, a widow and her child visit a cemetery, an old water carrier leers at a young girl who coyly draws her veil. Victor Champier described him as “an artist whose eyes have been rinsed in the splendid light of the Orient enabling him to capture the depth of its meaning and enjoy the happiness of sensing the strength and capacity of its spirit.”

EMPRESS EUGÉNIE

On her way to Egypt, to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal, Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, stopped in Istanbul. Abdülaziz put a palace in Beylerbey at her disposal and decorated it in French rococo style with an Oriental accent. Eugénie slept in a Syrian bed, richly inlaid with mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, and silver, and she bathed in a sumptuous hamam. She was even given the privilege of visiting the ladies in the sultan’s harem. For the first time in history, a sultan bowed before a foreign woman.

This visit began a chain of irreversible effects. The Turkish women living in harems suddenly acquired a taste for everything French. Francomania in Turkey equaled its French counterpart, Turquomania. Aristocratic Turkish ladies copied the empress’s appearance to the best of their ability, dividing their hair in the middle and spending endless hours making clusters of curls. High-heeled shoes replaced the curved-toed Turkish slippers. Skirts were suddenly favored over the shalwar (harem pants). Before the end of the century, the women were dressed by the French couture house of Worth, spoke several languages, and read Flaubert and Loti—yet some of them were still confined in harems.

PIERRE LOTI

In the hills of Eyub, overlooking the Golden Horn, is an open-air café called the Pierre Loti. The famous author once frequented it, under an assumed identity as a Turkish Bey. On some weekends, I went there with my friends. We sat under the century-old sycamores, sipping black tea served in samovars and digesting the view. What we saw were shipyards, paper factories, and enormous mountains of coal—no longer a “city of cut jasper,” no longer the Sweet Waters of Europe with myriad pleasure kayiks. But those images were superimposed on the real ones, because Loti had evoked them so well for us in his novels.

Born into a Huguenot family in Rochefort as Julien Viaud, Loti joined the Navy as a young man. His voyages took him to exotic and distant places not yet known by many, such as Easter Island, Senegal, and Tahiti. His novels were evocative and nostalgic; they spoke of melancholy, disenchantment, incurable solitude, separation, and death.

No place, however, enthralled him so much as Istanbul. It was love at first sight. He had found his muse, and he formed a lifelong love affair with her, producing two gems of Orientalist literature, Aziyade (1877) and The Disenchanted (1906).

“Behind those heavy iron bars, two large eyes were fixed on me. The eyebrows were drawn across, so that they met.… A white veil was wound tightly around the head, leaving only the brow, and those great eyes free. They were green—that sea-green which poets of the Orient once sang,” wrote Loti of Aziyade, a Circassian in the harem of a Bey, whose enigmatic and untouchable beauty enchanted him. Defying all danger, his servant Samuel arranged a nocturnal rendezvous. They met on a boat:

Aziyade’s barque is filled with soft rugs, cushions and Turkish coverlets—all the refinements and nonchalance of the Orient—so that it seems a floating bed, rather than a barque.… All dangers surround this bed of ours, which drifts slowly out to sea: it is as if two beings are united there to taste the intoxicating pleasure of the impossible.

When we are far enough from all else, she holds out her arms to me. I reach her side, trembling as I touch her. At this first contact I am filled with mortal languor: her veils are impregnated with all the perfumes of the Orient, her flesh is firm and cool.

It may sound a bit over the top: The prose is purple, and the fantasy boundless. But Loti and Aziyade have many such nights of pleasure on her boat. Finally, Loti’s ship has to leave; the lovers part. He promises to return. But he does not, and Aziyade dies of a broken heart.

When Loti returned to Istanbul twenty years later, it had become astonishingly Westernized. Though the harems still existed, a new breed of well-educated and outspoken young women were emerging. Envious of European women’s freedom, tired of wearing veils and being forced into marriages of not their choosing, they were acting up.

Loti had received a letter from such a woman, named Djénane, who entreated him to come to Istanbul. Beginning to age, tempted to see Aziyade’s land once again, he decided to return. Djénane and two accomplices arranged clandestine meetings with Loti in the most exotic and picturesque parts of Istanbul. They told him heartbreaking accounts of their miserable lives, in the hope of persuading Loti to write a novel about the oppression of harem women. The novelist was less interested in politics than in romance, so the women fabricated a fictional world of romance to inspire him, which came to an end when Djénane, like Aziyade, took her own life.

Loti returned to Paris and wrote The Disenchanted.

But the story does not end here. Soon after the writer’s departure, the women on whom the book was based also fled to Paris, where they became a cause célèbre, appearing at the most exclusive parties. They were written about, painted, and sculpted by the greatest artists of the era, among them Henri Rousseau and Auguste Rodin. Moreover, after Loti’s death, a French woman named Madame Lera, who wrote under the pseudonym Marc Helys, published Le Secret des désenchantées, which claimed that she herself had posed as Djénane with the help of her two Turkish friends; the three women had simply wanted to amuse themselves with Loti. Helys’s “revelation” was challenged, but the documents, letters, and journal entries she deposited at the Bibliothèque Français left no doubt as to the truth of her story.

Photograph of a 1905 drawing by Auguste Rodin, which depicts the heroines of Pierre Loti’s harem novel, The Disenchanted. Collection of the author

The story of The Disenchanted, which inspired my novel The Third Woman, is a great example of the fallacy of Orientalism. Loti was so caught up in the exotic woman of his imagination that the only way he could portray her was through a French woman playacting. It was also the greatest literary hoax of the twentieth century.

EMANCIPATION OF THE EAST

The publication of The Disenchanted not only stirred up scandal but was also one of the elements that brought the suffragettes to the rescue. Turkey was suddenly flooded with European women who were appalled at the situation of their sisters, still living under such male dominance. It was a great feminist cause to set out on a crusade to free these unfortunates. Their predecessor, Sir Richard Burton’s wife Isabelle, would deliberately appear in low-cut dresses during social gatherings to set a provocative example, and in Lebanon, at an embassy reception, she had had the wives sit in chairs and ordered their husbands to serve them tea and cakes.

The movement to establish women’s rights so threatened the established order that in 1901 Sultan Abdülhamid II issued an edict prohibiting the employment of Christian teachers in harems, the education of Turkish children in foreign schools, and the appearance in public of Turkish women with foreign women. These restrictions only served to force the issue among women, who organized secret meetings. Messages were carried from harem to harem—protected by the certainty that Moslem women are never searched.

At the same time, the Young Turks, faced with the stark reality of a diseased empire, shed their intellectual idealism and began mobilizing in Macedonia. In 1908, they established a constitutional monarchy and greatly curtailed the power of the sultan. It would take another decade for major changes actually to become effective in Turkish society, but by the 1920s women became fully integrated into public life. The revolutionary leader Kemal Atatürk challenged: “Is it possible that, while one half of a community stays chained to the ground, the other half can rise to the skies? There is no question—the steps of progress must be taken to accomplish the various stages of the journey into the land of progress and renovation. If this is done, our revolution will be successful.”

Veils came off. The massive layers of clothing were shed and, with them, the years of suppression and isolation. Harems were declared unlawful; polygamy abolished.

THE LAST PICTURE

One of the most touching and strange scenes took place at the Seraglio. Relatives of the harem women were summoned to Istanbul to claim their daughters and sisters. Circassian mountaineers and peasants came in droves, clad in the picturesque costume of country folk. They were formally ushered into a large hall of the Seraglio where the ex-sultan’s kadins, concubines, and odalisques came to greet them. The contrast between the elegantly dressed ladies of the palace and the rugged peasant men was dramatic. Everywhere people fell into the arms of their long-unseen loved ones, sobbing uncontrollably. But the most heartbreaking picture was the faces of the women for whom no one came. Kismet left them to the hollow echoes of a dead institution, which, even in their freedom, they could not escape. They remained at the Old Palace, relics of the past, trapped in their own liberation. Artists continued immortalizing these beauties with stories of perfumed handkerchiefs, roses, and poems dropped from behind latticed windows.