These flower-women, women-flowers, he prefers them to any others, and spends his nights in the hothouses where he hides them as in a harem.

—Guy de Maupassant, Un Cas de Divorce (1886)

I was born in an old house in Izmir, Turkey, which had previously been inhabited by a pasha who had a harem. I grew up listening to stories that could easily have come from the One Thousand and One Nights. People often whispered things about harems; my own grandmother and her sister had been brought up in one. Since then, I have come to see that these were not ordinary stories. But for me, as a child, they were, for I had not yet known any others.

My paternal grandmother, Zehra, was the first person from whom I heard the word harem and who made allusions to harem life. She was the daughter of a prosperous gunpowder maker in Macedonia. As was not uncommon until the twentieth century, she and her sisters had been brought up in a “harem”—which really means a separate part of a house where women lived in isolation, having no contact with men other than their blood relatives. The term does not necessarily imply the practice of polygamy.

Rarely did they go out; and when they did, they were always heavily veiled. The most poignant image I know is that of silk tunnels being stretched from the door of the house to a carriage, so that the ladies could leave without being seen from the street. The family had already arranged their marriages. None of them saw their husbands until their wedding day. Then they moved to his house, to live together with his mother and other women relatives—and occasionally another wife or two.

My grandmother married my grandfather when she was fourteen. He was forty and her father’s best friend. She was a simple, uneducated girl from Pirlepe. He was a respected scholar from Kavala. Ten years later, she would be widowed.

Threatened by the Balkan Wars, my grandparents left everything behind in Macedonia, including their parents, and fled to Anatolia. They sought refuge and settled down in Istanbul in 1906. My grandfather soon died, and my grandmother moved in with one of her sisters for a time. The two women brought their children up together, as one family. In 1909, with the fall of Sultan Abdülhamid II, harems were abolished and declared unlawful.

I do not remember very much of the house in Izmir (Smyrna) where I was born. In my memory, it faced the sea and was five stories high. (When I returned years later, I saw that it had only three stories.) It had a hamam where women in the neighborhood came together to bathe. Some of the windows were latticed, screening the outside world. A giant granite rock behind the house isolated it even more. It was said that sometime before us, an old pasha, his two wives, and other women had occupied the place.

When my grandmother, her three sisters, and friends gathered together, they told stories and argued about facts and details, rarely agreeing. We children participated in rituals that the women had transported from their harem days. Like many girls of my generation, we learned to make concoctions to remove hair, brew good coffee, distribute a sacrificed sheep’s entrails to the poor, cast spells, and give the evil eye to protect ourselves.

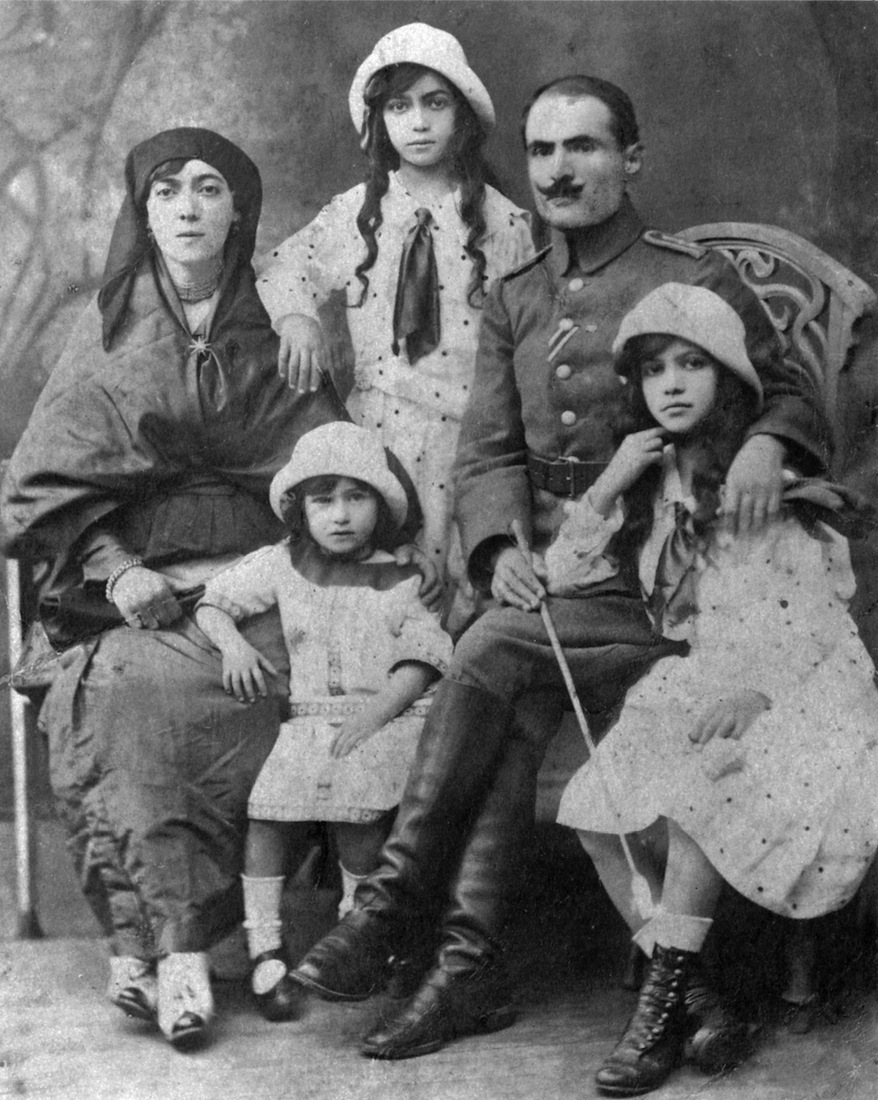

Meryem, my great-aunt, with her husband, Faik Pasha, and daughters (clockwise), Muazzez, Mukaddes, and Ayhan. Faik Pasha made a gift of orphan odalisques to my family.

When I was eighteen years old, I left Turkey and came to live in the United States. Fifteen years later, I returned to Istanbul to visit my family and sort out my impressions of my birthplace. I returned, carrying new baggage with me: an expatriate’s eye and a self-conscious awareness of art history and feminist rhetoric. It was not surprising, then, that I found myself fascinated with the recently restored harem apartments of Topkapi Palace—the Grand Seraglio, or the Sublime Porte, as it was known in the West. It had belonged to the Padishah, sultans of the Ottoman Dynasty, who had hidden away their women here from around 1540 through the early 1900s—during four hundred years of life and culture. All that remained now of the thousands of women who had lived in these rooms, in fantastic luxury and isolation, were their empty boudoirs, their echoing baths, and countless, impenetrable mysteries.

This visit to the harem of the Topkapi Palace haunted me. I was obsessed with the notion that these same stairways once felt the flying feet; these alleys heard the soft rustle of their garments. The marble floors of the baths were worn out from centuries of water running. The walls seemed to whisper secrets pleading to be heard. Obviously, more was concealed here than the popular notion of sensuality attached to the word harem or what I had learned from art history classes and childhood stories. It seemed as though I had stepped into a unique reality—a cocoon of women in their evolutionary cycle. Questions kept insinuating themselves. Why had we not studied the harem at school? We were taught ten years of Ottoman history and had to memorize the dates of all the wars and conquests and who killed whom. What had occurred here during all these years? Who were these women? What did they do from day to day? Why was it treated so perfunctorily?

I began searching in earnest for documents on harems—books, letters, travelogues, paintings, photographs—to help reconstruct a candid image of this veiled world. What I found were fragments—romanticized descriptions of the imperial harem by Western travelers, writers, or diplomats, a few smuggled letters and poems written by the women themselves, and tedious studies by historians whose primary interest was royal life and palace politics, not the uncounted, unnamed women of the harem.

Simultaneously I had to probe deeper into my own family history. When I expressed my need to find out everything about harems, on which nothing definitive had been written, relatives and friends came forth. They helped me remember things. They showed me strange books and letters. They shared ephemeral stories, things that had happened a long time ago, so that I could write about them.

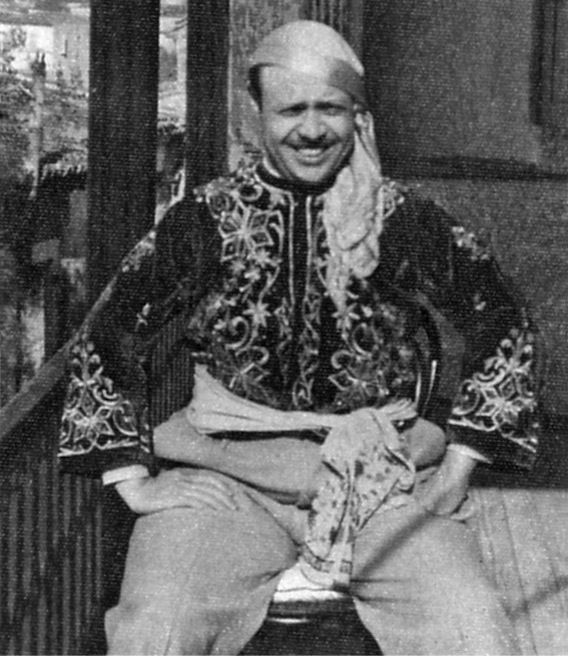

My aunts Muazzez and Mukaddes (dressed in a World War I army uniform). Since, during the early twentieth century, it was usually inappropriate for women to be photographed with men, some posed with other women dressed in men’s clothes.

Aunt Ayhan with baby Genghiz. Ayhan was the beauty in the family. Even Kemal Atatürk, Turkey’s great reformer and first president, admired her.

Physical and spiritual isolation of women and polygamy, I discovered, were not unique to Turkey. Harems existed throughout history in different parts of the Asian world, known by different names, such as purdah (“curtain”) in India and, in Persia, enderun or zenane. In China, the Forbidden City of Peking also had cloistered women, protected and guarded by eunuchs.

During the sixth century B.C., King Tamba of Banaras had a harem of some sixteen thousand women. A fifteenth-century sultan of Malwas, Ghiyas-ud-di Khilji, built Jahaz Mahal, the “ship palace,” to accommodate his large harem. Kublai Khan, the Mongol leader, had four empresses and around seven thousand concubines. It is rumored that every two years he would get rid of a couple hundred and replace them with a fresh supply. Emperor Jahangir of India also maintained a harem of six thousand women, as well as a thousand young men-in-waiting for those times when his appetite tended toward the other gender. But the most highly and extensively developed harem was that of the Grand Seraglio. What happened there came to be seen as a paradigm of all harems.

In the Seraglio alone, thousands of women lived and died with only each other to know of their lives. By piecing together the fragments collected over the years, I hoped to gain a glimpse into this mysterious, beautiful, and unbelievably repressive world concealed for so many centuries behind the veil. What will these women tell us, about themselves and about ourselves?