I am a harem woman, an Ottoman slave. I was conceived in an act of contemptuous rape and born in a sumptuous palace. Hot sand is my father; the Bosphorus, my mother; wisdom, my destiny; ignorance, my doom. I am richly dressed and poorly regarded; I am a slave-owner and a slave. I am anonymous, I am infamous; one thousand and one tales have been written about me. My home is this place where gods are buried and devils breed, the land of holiness, the backyard of hell.

—Anonymous

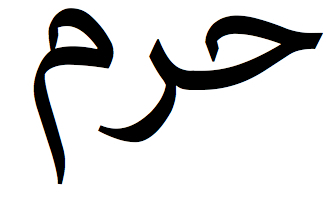

MEANING

The word harem, derived from the Arabic haram ( ), means “unlawful,” “protected,” or “forbidden.” It is a term that implies respect for religious purity. The sacred area around Mecca and Medina is haram, closed to all but the Faithful.

), means “unlawful,” “protected,” or “forbidden.” It is a term that implies respect for religious purity. The sacred area around Mecca and Medina is haram, closed to all but the Faithful.

In its secular use, harem refers to the separate, protected part of a household where women, children, widowed relatives, and female servants lived in seclusion and privacy, cloistered from all but the master of the house and their immediate male relatives; in a noble or wealthy house, the harem would be guarded by eunuch slaves. The term may also be applied to the women themselves. In the West, harem implies a “house of joy,” a less-than-religious acknowledgment of the master’s exclusive rights of sexual foraging.

ORIGINS

Harem, a world of isolated women, is the combined result of several traditions. It suggests a clear idea of the separation between things, the sublime duality of the sacred and profane, whereby reality is divided into mutually exclusive categories and controlled by strict regulations known as taboos. Under such a system, men and women are among the first to be divided. Women symbolize passion; men, reason. Eve was the temptress, and patriarchal systems throughout the ages have tended to regard all women as such.

Scripture notwithstanding, there was a world before the time of Adam and Eve—in some places, a prepatriarchal world. In the Sumerian, Egyptian, and Greek civilizations, for instance, women occupied high positions of spiritual power and ascended to the thrones of the gods. Under these essentially matriarchal systems, both female and male deities controlled the destinies of human beings and animals. They were equally powerful.

The white goddess of birth, love, and death is the earliest-known deity. She was personified as the moon, full, new, and old, and was worshiped under infinite names, as Isis, Ishtar, Artemis, and others. She was the Great Goddess in her multifarious forms.

At the dawn of civilization, clans migrated continually in search of food and game, everyone collaborating in a tribal act. In this set-up, the forms of subsistence left no surplus, and the concepts of private ownership, class distinction, masters and slaves did not exist.

As agriculture began to provide a more reliable source of food than hunting and gathering, endless migration became less essential for survival. Tribes rooted down, claiming land and territory. At first, as incarnations of the connection between seeds and growing things, women rose to a privileged position in early societies. So did the female deities. Demeter, the Greek goddess of fertility, protected the crops; had she not been compelled to share her daughter, Persephone, with the male underworld, there could have been perpetual—rather than merely seasonal—abundance.

Eventually, agricultural knowledge created a surplus of food for some, making it possible to exploit others who did not have the means to secure their own subsistence. The ownership of private property, especially land, replaced communal sharing, splitting society into landowners and varying degrees of slaves. This development was concurrent with the decline of women’s spiritual prestige; they ceased performing religious rituals.

The mother was no longer the axis of the family; the father became the paterfamilias. In ancient Rome, familia meant a man’s fields, property, money, and slaves, all of which were passed on to his sons. Woman became part of man’s familia, his property. And polygamy was established as an important part of an economic system in which a man needed hands to maintain his livelihood.

The story of Adam and Eve appears in Judaism as a demonstration that woman is sinful and that her sin is sex. The story affirms a severance of body from soul, which Christianity embraced and exaggerated by representing Christ as a holy male born of a woman who had conceived asexually; Christ was so chaste that he was deprived of women and sexual expression.

Odalisque, early 17th century, Miniature from the Murabba Album, Topkapi Museum, Istanbul. The woman appears to be a version of Eve, with a pomegranate, an ancient fertility symbol.

This cornerstone of Judeo-Christian belief divided human beings from themselves, opposing to a humanitarian conviction of the essential goodness of the body, inherited from ancient Egyptian and Greco-Roman religions, a belief that the physical reality of the here and now was to be despised in dreams of “another” world of infinite and insubstantial spirituality.

God had created man in his own image; God was spirit. But woman was the flesh or body, and the body was an animal dominated by passion, sensuality, and lust. Man personified the heavens, and woman could never be whole until married to one. By the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus had promulgated their belief that women were capable of engaging in intercourse with Satan. On these grounds, the Inquisition identified and condemned certain women to be burned alive. Female spiritual submission was thus complete.

Men, on the other hand, allowed themselves plenty of sexual freedom under the patriarchal system. Prostitution increased rapidly; indeed, a large portion of the Catholic Church’s income came from the brothels, and Martin Luther’s Reformation was partly an attempt to end this hypocrisy. As for Islam, it imposed segregation and the veil upon women, claiming they could not be trusted and had to be kept away from men (other than close relatives), whom they could not help but seduce. The need for special, secluded dwelling places for women became imperative—not to protect their bodies and honor, but to preserve the morals of men.

POLYGAMY

Polygamy is the practice of having more than one spouse; in common usage, this most often means more than one wife. Technically, polygyny is having more than one wife, and polyandry, more than one husband. Founded on agrarian necessity, polygamy has been part of many religions.

Islam holds women in particularly low esteem, considering them intellectually dull, spiritually vapid, and valuable only to satisfy the passions of their masters and provide them male heirs. “Woman is a field; enter her as you wish,” says the Qur’an (2:223). “Men have dominion over women” (4:34).

A man is allowed four wives if he is able to keep them all in the same style and can share with them equal amounts of affection and wealth. The Prophet Mohammed had altruistic intentions when he sanctioned polygamy, seeing it as a solution to the pre-Islamic practice of female infanticide, as well as a practical way to deal with the surplus female population. It was mainly an economic measure, having little to do with Western romantic and erotic stereotypes.

In Arabic, the first wife is called hatun (the great lady) and the second, durrah (parrot). If a husband wanted to get rid of any of his wives, he could divorce them with relative ease by saying, before a kadi (judge), “I divorce thee” three times. A wife could not initiate a divorce; she had few marital rights. A man could also own as many female slaves as he pleased.

Multiple wives were expensive, not only to maintain, but also because it was the custom to raise a “bride price” for each wife. Poor men could barely afford one wife, although they sometimes took two anyway—separating the women in their humble dwelling by a mere curtain. Wealthy men sometimes exceeded the four “allowed” by the Islamic law and made a display of their wives as a status symbol. However, since too much show attracted tax collectors and other undesirables, this was not always a wise idea.

SLAVE MARKETS

The slave trade had flourished in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean since the Mesopotamian civilizations, two thousand years before Christ. Young boys and girls, captured in war or paid as tribute by their fathers or local rulers, were available for purchase on the open market in major cities. Alexandria and Cairo served as the main emporiums.

John Faed, Man Exchanging a Slave for Armor, ca. 1858, Oil on board, 171⁄4 × 24 in., Private collection

The slave markets intrigued distinguished travelers and writers. Within a ten-year period, we hear varying descriptions:

The slave market was one of my favorite haunts.… One enters this building which is situated in a quarter the most dark, dirty and obscure of any at Cairo by a sort of lane.… In the center of this court, the slaves are exposed for sale and in general to the number of thirty to forty, nearly all young, many quite infants. The scene is of a revolting nature; yet I did not see as I expected the dejection and sorrow as I was led to imagine watching the master remove the entire covering of a female—a thick woollen cloth—and expose her to the gaze of the bystander.

William James Muller (1838), British Orientalist painter

Not the least of their attractions was their hair; arranged in enormous plaits, it was also entirely saturated in butter which streamed down their shoulders and breast.… It was fashionable because it gave their hair more sheen, and made their faces more dazzling.

The merchants were ready to have them strip: they poked open their mouths so that I could examine their teeth; they made them walk up and down and pointed out, above all, the elasticity of their breasts. These poor girls responded in the most carefree manner, and the scene was hardly a painful one, for most of them burst into uncontrollable laughter.

Gerard de Nerval, Voyage en Orient (1843–51)

When the dahabeeahs returned from their long and painful journeys on the Upper Nile, they install their human merchandise in those great okels which extend in Cairo along the ruined mosque of the Caliph Hakem; people go there to purchase a slave as they do here to the market to buy a turbot.

Maxime du Camp, Souvenirs et paysages d’Orient (1849)

Living in rooms opposite these slave girls, and seeing them at all hours of the day and night, I had frequent opportunities of studying them. They were average specimens of the steatopygous Abyssinian breed, broad-shouldered, thin-flanked, fine-limbed, and with haunches of a prodigious size.… Their style of flirtation was peculiar.

“How beautiful thou art, O Maryam!—what eyes!—what—”

“Then why—” would respond the lady—“don’t you buy me?”

“We are of one faith—of one creed, formed to form each other’s happiness.”

“Then, why don’t you buy me?”

“Conceive, O Maryam, the blessing of two hearts.”

“Then, why don’t you buy me?”

And so on. Most effectual gag to Cupid’s eloquence!

Sir Richard Burton, Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah (1853)

Edmund Dulac, Illustration to Quatrain XI of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1909), Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York.

“With me along the Strip of Herbage strown

That just divides the desert from the sown,

Where name of Slave and Sultan is forgot—

And peace to Mahmud on his golden throne?”

The Turkish tribes, including the Ottomans, practiced polygamy prior to the conquest of the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, in 1453. Sultan Mehmed II, known to history as “the Conqueror,” was obsessed with making his new metropolis, which he called Istanbul, a replica of Constantine’s—only more opulent. He allowed the Valide sultana (mother sultana) to organize her house as nearly as possible in the manner of the gynaecea (women’s apartments) of Empress Helen, widow of Constantine. The gynaecea were situated in the remotest part of her palace, lying beyond an interior court; women lived here separately, divided into task groups. Mehmed himself adopted such Byzantine customs as the sequestering of royalty, establishing a palace school, and the keeping of household slaves. The Islamic practice of polygamy combined neatly with these Byzantine customs and resulted in the harem.

The early Ottoman sultans had married daughters of Anatolian governors and of the Byzantine royal family. After the conquest of Constantinople, it became customary to marry odalisques. The women in harems, except those born in it, came from all over Asia, Africa, and, occasionally, Europe.

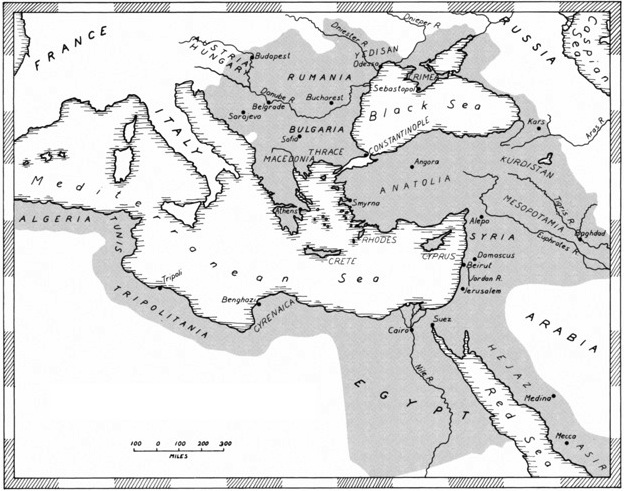

According to ancient legend, the Seraglio Point, a magnificent isthmus extending between the Marmara Sea and the Golden Horn, was named by the Delphic Oracle as the best site for a new colony and became the Acropolis of ancient Byzantium. A decade after the conquest, Mehmed the Conqueror built Topkapi Palace—known in the West as the Grand Seraglio or the Sublime Porte—on the same sacred point.

In his poem “The Palace of Fortune” (1772), Sir William (Oriental) Jones invokes a palace of such opulence:

In mazy curls the flowing jasper wav’d

O’er its smooth bed with polish’d agate pav’d;

And on a rock of ice, by magick rais’d

High in the midst a gorgeous palace blaz’d.

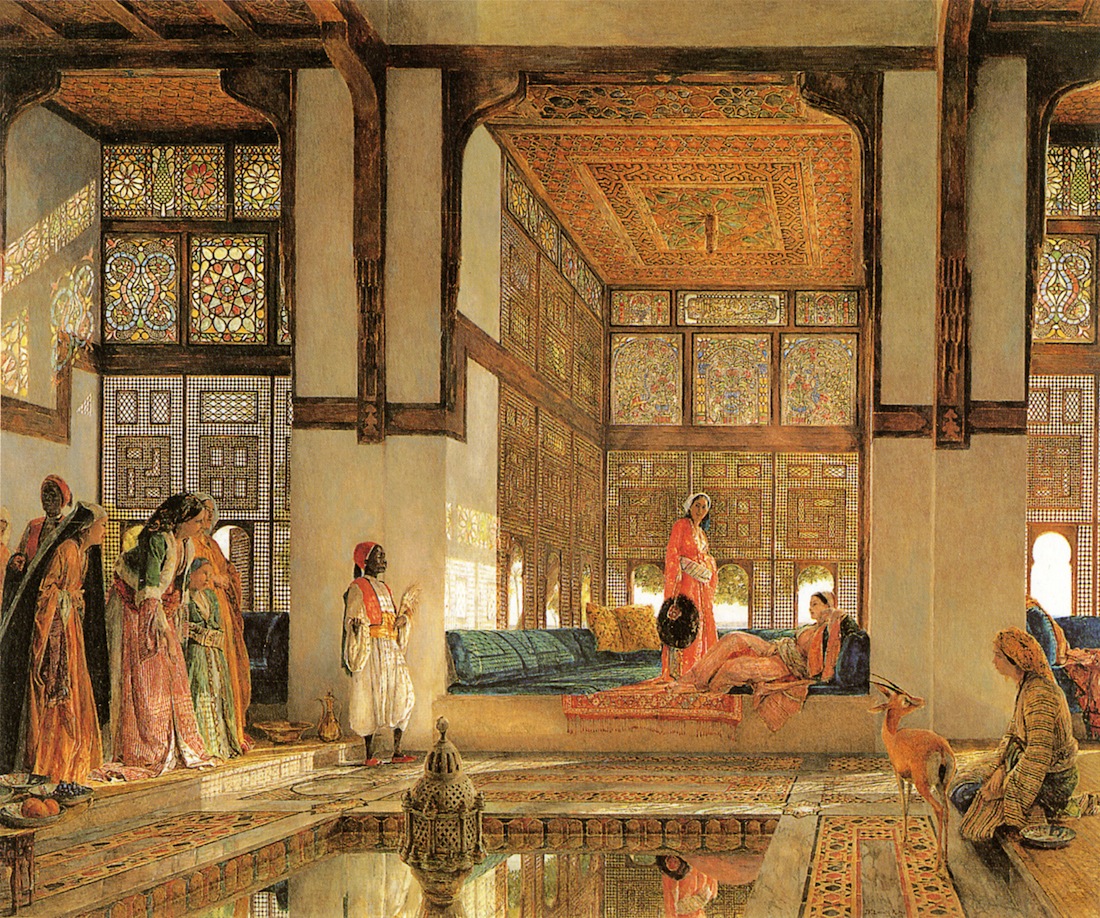

John Frederick Lewis, The Reception, 1873, Oil on panel, 25 × 30 in., Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut; Paul Mellon Collection

The Seraglio was the seat of imperial power, housing thousands of people involved in the sultan’s personal and administrative service. The most private section, carefully separated from the rest of the palace, was the sultan’s harem, which moved to the Seraglio for the first time in 1541, with Sultana Roxalena, and lasted until 1909. The ever-changing female family lived, loved, and died here for four centuries. It became the ultimate symbol, the quintessence of harem, the system of sequestering women.

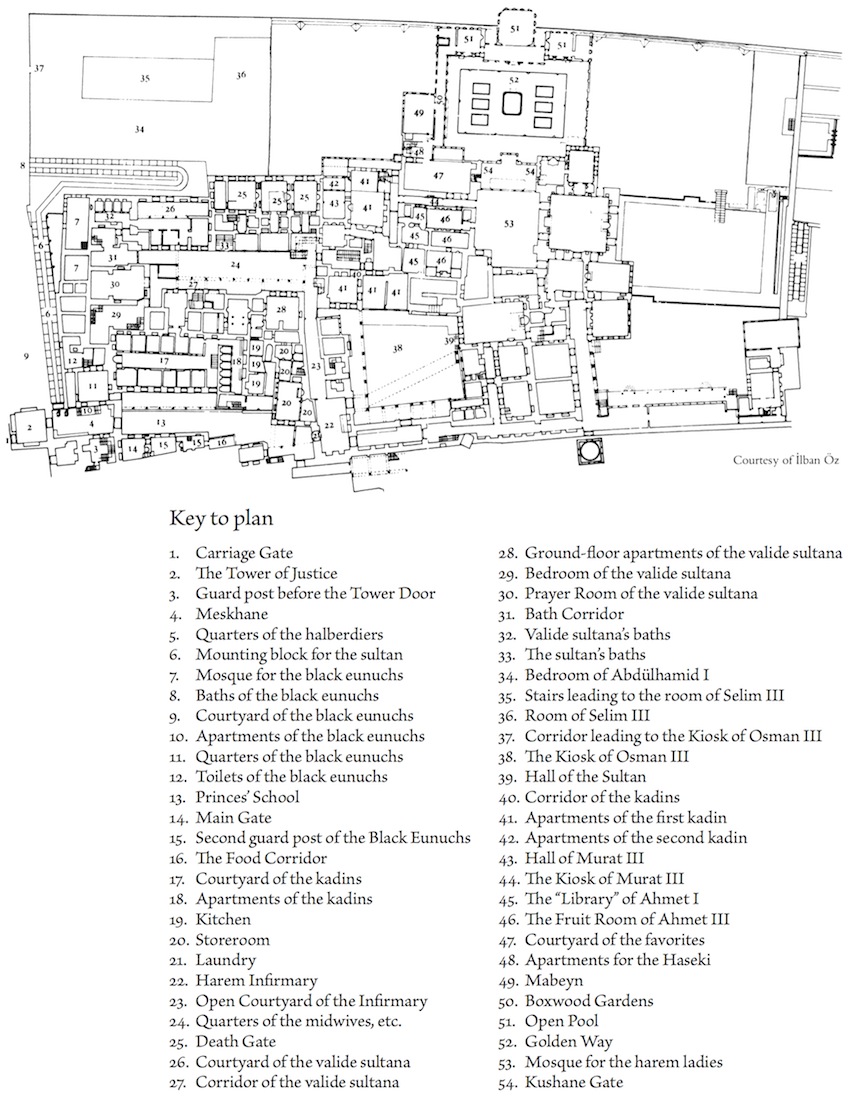

The harem was located between the Mabeyn (Court)—the sultan’s private apartments—and the apartments of the chief black eunuch. It had almost four hundred rooms centered around the Courtyard of the Valide sultana, containing the apartments and dormitories of other women.

The Carriage House and the Bird House, which connected the harem to the outside world, were carefully guarded from within by the corps of eunuchs and, outside, by halberdiers, or royal guards. The Carriage House was the real entry to the harem; all contact with the outside was made through its gate, which opened at dawn and closed at dusk.

The eunuchs’ quarters led into a courtyard, which opened on the right to the Golden Road, in the center to the Valide sultana’s quarters, and on the left to the apartments of the odalisques. The luxury of the living quarters depended on the status of the personage occupying them. The sultan, of course, had the most opulent accommodations. High-ranking women had private apartments, whereas the novice odalisques and eunuchs lived in dormitories.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the population of the harem dropped from over a thousand women to a few hundred as a result of the young princes being assigned governorships in various provinces of the empire. They departed from the Seraglio, escorted by their own harems. After the seventeenth century, however, with reforms in the inheritance laws that allowed the princes to live in the palace with their own women—albeit as captives of the Kafes (the Golden Cage)—the overall harem population increased to almost two thousand. But there seems to be a contradiction here, since we are told that the women in the harems of the Golden Cage were sterilized so that they would not produce offspring.

At its zenith, the Ottoman Empire was vast, stretching from the Caucasus Mountains to the Persian Gulf, from the Danube to the Nile. The history of the Seraglio and its harem symbolizes the fluctuating fortunes of the empire. The great expense of upkeep, the ruthless rivalry among the women, intrigues that influenced political affairs, and, ultimately, the exquisite beauty of these women of many nationalities fascinated the entire world—but no outsider would be allowed behind its walls. Foreign ambassadors and traveling artists and writers reported accounts obtained from peddlers or servant women who had once lived there, but such narratives were often muddled by wishful exoticism. To this day, the reliability of these stories is difficult to ascertain.

ACQUISITION OF SLAVES

Young girls of extraordinary beauty, plucked from the slave markets, were reserved for the Padishah’s court, often as gifts from his governors and foreign dignitaries. Also, among the singular, lasting privileges of the Valide sultana was the right to present her son with a new slave girl on the eve of Kurban Bayram (the festival of the sacrifice) each year.

The girls were non-Moslems, uprooted at a tender age. The fair, doe-eyed beauties from the Caucasus region were the most in demand. These Circassians, Georgians, and Abkhazians were proud mountain girls, believed to be the descendants of the Amazon women who had lived in Scythia near the Black Sea (and who had swept down through Greece as far as Athens, waging a war that nearly ended the city’s glamorous history). Now they were being kidnapped or sold by impoverished parents. A customs declaration from around 1790 establishes their worth quite clearly: “Circassian girl, about eight years old; Abyssinian virgin, about ten; five-year-old Circassian virgin; Circassian woman, fifteen or sixteen years old; about twelve-year-old Georgian maiden; medium tall Negro slave; seventeen-year-old Negro slave. Costs about 1000–2000 kurush.” In those days one could buy a horse for around 5000 kurush.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Odalisque and Slave, 1842, Oil on canvas, 30 × 411⁄2 in. Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore

The promise of a life of luxury and ease overcame parental scruples against delivering their children into concubinage. Circassian and Georgian families often encouraged their daughters to pursue the path of slavery: “Circassians take their own children to the market, as a way of providing for them handsomely … but the blacks and Abyssinians fight hard for their liberty,” reported Lucie Duff Gordon in her 1864 travel diary.

TRAINING OF ODALISQUES

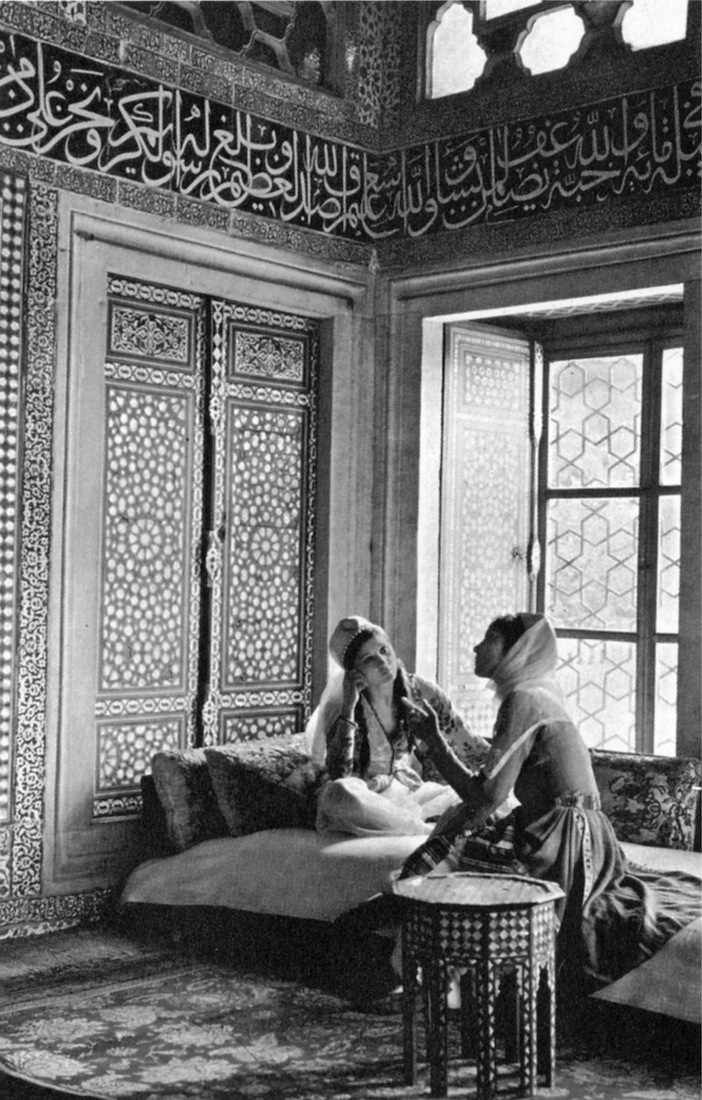

Before admitting the slave girls into the Seraglio harem, trained eunuchs carefully examined them for physical imperfections, such as pregnancy. If a girl were found to be satisfactory, the chief eunuch presented her to the Valide sultana for her approval. Once confined within the Seraglio, her Christian name was replaced with a Persian one that suited her particular qualities. If she had rosy cheeks, they called her Gulbahar; if she had ivory skin, Akbeyaz. Immediately converted to Islam, the new odalisque began an arduous training in the palace etiquette and Islamic culture.

Rudolph Ernst, Idle Hours in the Harem, ca. 1900, Oil on panel, 253⁄8 × 321⁄8 in., Private collection

The word odalisque comes from oda (room) and means literally “woman of the room,” implying a general servant status. They were also called halayik or cariye. Odalisques with extraordinary beauty and talent began their training as would-be concubines—learning to dance, recite poetry, play musical instruments, and master the erotic arts. Twelve of the most attractive and gifted ones were selected as gedikli, the sultan’s personal attendants, responsible for dressing and bathing him, doing his laundry, and serving his food and coffee.

Gio Maria Angiolello, an Italian youth who was captured by Mehmed II and stayed in his service until the sultan’s death, wrote in his Historia Turchesca (1480) that these girls were taught writing and religion, and trained in skills like sewing, embroidery, playing musical instruments, and singing. They were gifted women.

If the sultan was pleased with their services, he kept them for himself or—in the case of those who had not yet become his concubines—gave them as gifts to one of his high officials. According to Moslem etiquette, the official had to free the girl before marrying her. Their courtly charms and breeding, as well as their important connections within the Seraglio, made these women highly desirable.

Some odalisques were placed in the service of the Valide sultana, the kadins, the sultan’s daughters, or the chief eunuchs. Girls endowed with sturdy bodies became servants or administrators. Each novice was assigned to the oda of a Kalfa, an important lady in charge of a particular harem department. These “cabinet ministers” had intriguing names, such as mistress of the robes, keeper of the baths, keeper of the jewels, reader of the Qur’an, keeper of the storerooms, mistress of the sherbets, and head of table service. It was not impossible for an odalisque to climb up the ladder of the hierarchy and achieve the highest ranks in the Imperial Harem. On the other hand, if she happened to lack any particular talent, or manifested undesirable qualities, she was likely to be resold in the slave market.

SULTANAS

The sultan was a godlike entity, before whom no one could speak or raise their eyes. Contrary to the myth of the sultan throwing a handkerchief at the girl he intended to spend the night with, the actual means of favoring an odalisque was both less casual and less flamboyant: the chief black eunuch secretly escorted the girl into his majesty’s chamber. Seventeenth-century traveler Sir Paul Rycaut writes: “If the Sultan was pleased with the cariye, he would put her under the custody of the Mistress of the House. Only after she earned high rank—becoming, for example, an Ikbal (favorite)—would her relationship to the sultan be publicized. The girl would be returned to the harem with just as pompous a ceremony as her admittance to the Sultan’s bed. She would be bathed ceremoniously and moved into a private apartment and given a barge, carriage, and slaves.”

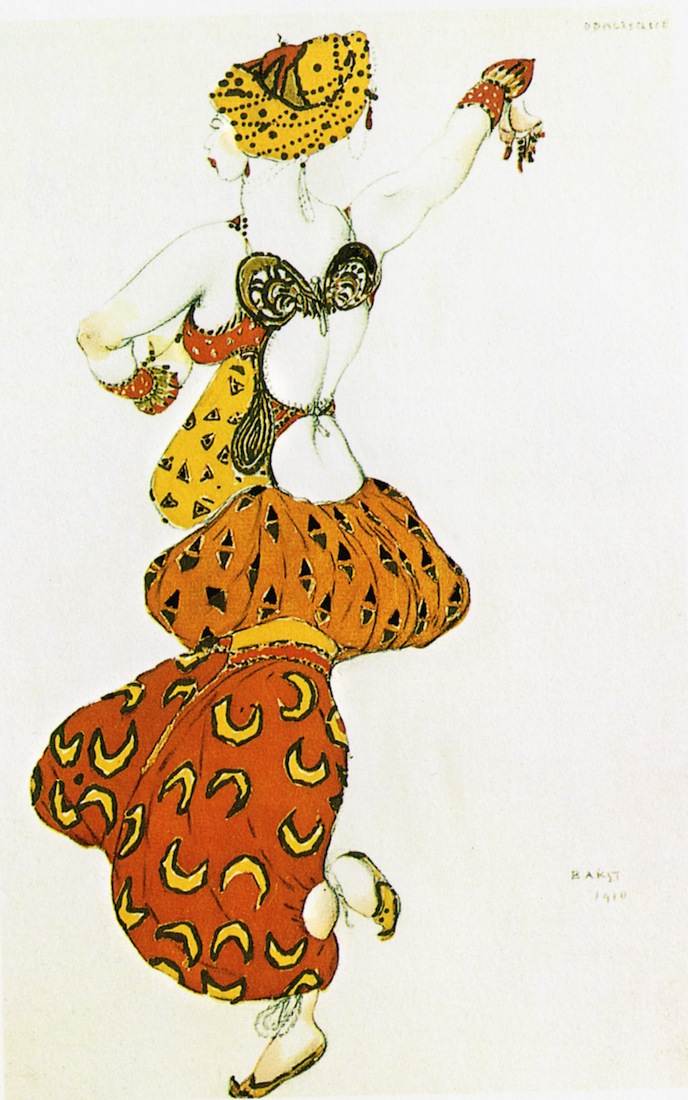

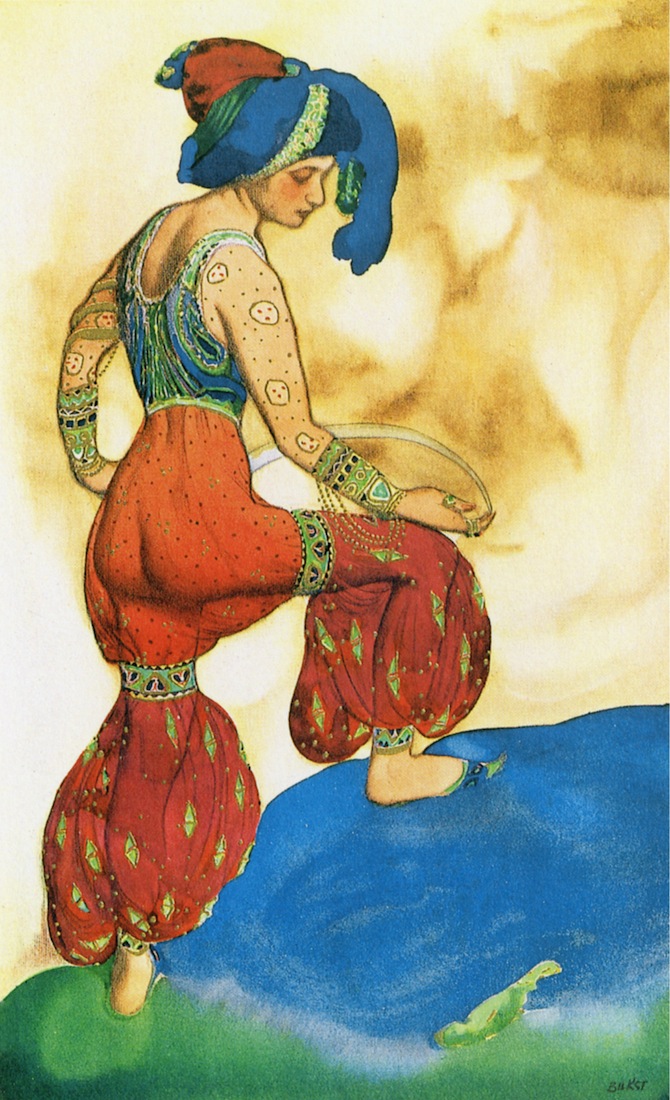

Leon Bakst, Odalisque. Costume design for the Diaghilev ballet Scheherazade, which featured the legendary Karsavina and Nijinsky, 1910. Watercolor and gold on paper, Private collection

When a favorite gave birth to the sultan’s child, she was elevated to the position of kadin or Haseki sultana. If, perchance, the child was a boy and became the sultan, his mother became the Valide sultana—the ruler of the harem and the most powerful woman in the empire. A Moslem man believed that heaven lay beneath his mother’s feet. After all, he could have as many wives and slaves as he wanted, but he had only one mother. He entrusted her with his most private and personal possessions—his women.

Competition for the coveted position of Valide was vicious, and the stakes were high. Constant rivalries and feuds kept hearts pounding, brains alert. A seventeenth-century document in the Topkapi Palace archives describes the rivalry between Gülnush Sultana and the odalisque Gülbeyaz that led to a tragic end. When Sultan Mehmed IV grew enamored with Gülbeyaz, the Haseki sultana Gülnush, who was still in love with the sultan, became madly jealous. One day, as Gülbeyaz was sitting on a rock and watching the sea, Gülnush quietly pushed her off the cliff into the water below.

Royal motherhood provided immense power and wealth, but very little security or feeling of peace. For a woman, to conceive was only to begin a perilous journey of self-defense, requiring great wit and courage. The prying eyes of jealous rivals were keen, and the threat to the mother or the potential heir was an everyday reality. Since a young prince stayed in the harem with his mother and nursed until puberty, his mother lived in constant stress. Kösem Sultana’s conspiracy to assassinate a child prince, Sultan Mehmed IV, and Roxalena’s banishment of prince Mustafa are two examples we will discuss later.

With the ascension of a new sultan, the wives of his predecessor, along with their entourages, were sent to the Old Palace, known as the Palace of Unwanted Ones or the Palace of Tears. Their apartments in the Seraglio were torn down, and new ones erected and decorated for the next occupants—not that those occupants were always satisfied with their accommodations, no matter how luxurious:

Dearest Kalfa,

I have heard from someone that she will be moving to the apartment which should be mine. No! As the earth is old, so do I want that apartment myself. I cannot bear a younger woman occupying such a spacious place, and if our mighty master heard my plea he wouldn’t object. Please, convey this to the valide sultana with my deepest respects. Why should she move there and I stay where I am? I must insist on my seniority privileges. If this cannot be changed, I will simply not move to the Seraglio, I swear. But if she refuses to, that’s a whole other affair. I will die rather than to let her have that beautiful apartment.

Letter from Behice Sultana to the Kalfa (mistress of the house) (1839)

EUNUCHS

To guard their women, sultans retained an immensely valuable corps of eunuchs, at times as many as eight hundred strong. Eunuchs were male prisoners of war or slaves, castrated before puberty and condemned to a life of servitude. The white eunuchs served in the Selâmlik, where the sultan met with other men. The black eunuchs looked after the women. The chief black eunuchs exercised great political power in court, serving as the most important link between the sultan and his mother. Officially his position was as important as that of the grand vizier.

Since they were often witnesses to the most intimate secrets of the harem and also had access to the outer world of powerful men, the eunuchs were potentially the most corrupt element of palace society. Surrounded by women trained to arouse passion, they were forever confronted by the loss of sexual prowess. Some compensated by becoming skillful intriguers, thus translating resentment into vengeance, like the creature in Montesquieu’s Persian Letters:

The Seraglio is my Empire; and my ambition, the only passion left in me, finds no small gratification. I mark with pleasure that my presence is required at all times; I willingly incur the hatred of all these women, because it establishes me more firmly in my post. And they do not hate me for nothing, I can tell you: I interfere with their most innocent pleasures; I am always in the way, an insurmountable obstacle; before they know where they are, they find their schemes frustrated.

The palace dwarf, also a eunuch, was a kind of court jester. Since he presented little threat to the male ego, he often was included in the most intimate situations: an eighteenth-century album of miniatures shows a dwarf entertaining a woman as she gives birth.

DYNASTY

The laws of inheritance decreed that the sultanate pass to the oldest living male member of the family, rather than from father to son. Mehmed the Conqueror, skilled in court intrigue, formulated the regulations that governed Ottoman policies for centuries. He sanctioned a sultan’s killing his male relatives to secure his throne for his own offspring—which resulted in atrocities, as in 1595, when Mehmed III’s nineteen brothers, some of them infants, were murdered at the instigation of his mother, and seven of his father’s pregnant concubines stuffed into sacks and thrown into the Sea of Marmara:

After the burial of the princes, the populace gathered in crowds outside the palace to watch their mothers and the other wives of the dead sultan leave the palace. All the coaches, carriages, horses, mules of the palace were employed for this purpose. Besides the wives of the sultan, his twenty-seven daughters and over two hundred odalisques under the protection of eunuchs were taken to the Old Palace.… There, they could cry as much as they wished in mourning for their dead sons.

Ambassador H. G. Rosedale, in Queen Elizabeth and the Levant Company (1604)

In 1666, Selim II issued an edict that softened the Conqueror’s cruel decree, allowing the imperial princes to survive, but not to participate in any public activities during the life of the reigning sovereign. From then on, the princes were kept secluded in the Kafes (Golden Cage), an apartment adjoining the harem but separated from it by a gate called the Djinn’s Kapi (Genie’s Gate), which was off-limits to everyone else in the harem.

The princes spent their lives in isolation, except for the company of a few concubines whose ovaries or uterus had been removed. If, through some oversight, any woman became pregnant by an outcast prince, she was immediately drowned. Guards, whose eardrums had been perforated and tongues slit, served the princes. These deaf-mutes were guardians—as well as potential assassins.

Life in the Golden Cage was racked by fear and endured in ignorance of events occurring outside. If a prince lived long enough to ascend to the throne, he was most likely unfit to rule an empire. When Murad IV died in 1640, his successor Ibrahim I was so terrified of the crowd trying to enter the Cage to proclaim him sultan that he barred the door and would not come out until Murad’s dead body was displayed. Süleyman II, during the thirty-nine years he spent in the Kafes, became an ascetic and a master calligrapher. Later, as the sultan, he had a deep longing to return to his former isolation and solitude. Other princes, like Ibrahim I, indulged in spasms of violent debauchery, taking vengeance for their lost years.

DEATH

The lives of the harem women were short. Endless stories of brutal murders and poisonings spread to the rest of the world. Henry Lello, English ambassador to the Ottoman court in 1600, cited the impossibility of enumerating the intrigues in the harem. Women were drowned, seized by the chief black eunuch, who stuffed them in sacks, tied the neck tightly, loaded them in a rowboat, and assisted in throwing the sacks overboard.

In 1665, some women in the court of Mehmed IV, accused of stealing the jewels from the cradle of one of the royal infants, started a fire to cover up the theft. The fire caused considerable damage in the harem and other parts of the Seraglio. The women were immediately strangled.

A story goes around that Mehmed the Conqueror killed his own wife Irene with a stroke of his scimitar. Thus Irene became a martyr, and, like all martyrs, she was proclaimed a saint and consigned to paradise. “The fortunate fair who has given pleasure to her lord will have the privilege of appearing before him in paradise,” says the Qur’an. “Like the crescent moon, she will preserve all her youth and her husband will never look older or younger than thirty-one years.” Was Mehmed recalling these words when he took Irene’s life?

THE WORLD OF EXTREMES

The Grand Seraglio, the Golden Cage, and the harem were worlds of extremes—frightened women plotting with men who were not men against absolute rulers who kept their relatives immured for decades. The setting was rife with conflict, and frequent tragedies touched the innocent as well as the guilty. The sultan, or Padishah, known as the King of Kings, the Unique Arbiter of the World’s Destinies, the Master of the Two Continents and the Two Seas, and Sovereign of the East and the West, was himself the product of a union between a king and a slave woman. His sons and the entire Ottoman dynasty shared the same fate—kings born of slave mothers, procreating offspring with more slave mothers.

The Turks viewed these rapid changes in fortune, the flirtation of good and evil, as the workings of kismet or kader. They believed that a divine being had already shaped everyone’s personal destiny. Whether tragedy or luck touched life, it was kismet. The universal acceptance of kismet among slaves, as well as royalty, somewhat explains the acquiescence to the deprivations, tortures, and sudden misfortunes that occurred daily in the harem.

The common suffering often led to great compassion among the inmates of the exalted household. Deep bonds grew alongside jealousies and rivalries among women. To survive the turmoil and intrigue, they built strong and trusting relationships. To me, these bonds are the harem’s most touching secrets.

All that remains now of these women’s lives are latticed windows, labyrinthine corridors, marbled baths, and dusty divans. Still, tales of the women behind the veil live on, an echo of the pathos and the pleasure of the One Thousand and One Nights, a part of our memory and also a part of tonight.