Daily Life in the Sultan’s Harem

And slender-waisted [maidens] would visit us after the rest from their chambers,

Plump their buttocks, wearing rings upon their waists,

Shining their faces, closely veiled, restraining their glances, dark-eyed,

Luxuriating in [heavenly] bliss, drenched in ambergris,

Sweeping along the robes of [their] charms, and undergarments, and silk,

Never seeing the sun save as a pendant [glimpsed] through the gaps of [their] curtains.…

—Abu’l-Atahiya (748–825), Arab poet; translation by A. J. Arberry

HAREM WALLS

The old Turkish proverb, “Our private lives must be walled,” reflects an attitude of Ottoman society. Harems literally walled the women. The historian Dursun Bey wrote, “If the sun had not been female [Shems, the word for sun, is feminine], even she would never have been allowed to enter the harem.” Actually, Gülbeyaz, favorite of Mehmed IV, wrote in the seventeenth century that “The sun never visits us. My skin is like ivory.”

Intimacies rarely found their way outside the walls; very few personal accounts of day-to-day life in the harem are available. To gain a sense of its domestic pace and private rhythms, we can only assemble fragments from numerous, often contradictory, sources. A beguiling image does slowly materialize.

In the painting The White Slave by Lecomte de Nouy, a dark-haired beauty smokes a cigarette as she stares into empty space. What does she do on any given day, one day in an endless series melting into months and years, with only the harem walls to witness the passage of her life? What about the chocolate-colored girl in the background, squeezing out a towel? What is she thinking about? In Frederick Goodall’s A New Light in the Harem, a woman reclines on a divan while a black nurse amuses a naked baby with a birdlike toy. What are this reclining woman’s dreams? Is she the child’s mother, whose life depends on the whim of one all-powerful ruler, the sultan, and one all-powerful God, Allah?

How many of the harem women accepted their fate as “written in their foreheads,” after being captured or bought as slaves and forced to convert to Islam? We know from a collection of letters written by various sultanas, Harem’den Mektuplar (1450–1850), that there were literate women in the harem who never mastered the language of their captors. Did Christian and Jewish women secretly pray to their God, begging for deliverance from the punishment He had visited upon them? Did they live with the shame of believing their souls could never be redeemed?

We have evidence that the black arts were practiced in the harem. Fortune-telling, magic, and Cabalism all had their secret and overt adepts. The women looked for ways to predict the future, to ease the present, and to exorcise the demons incubating within.

And we hear of the rebels, women who succumbed to the passions of their hearts, risking affairs and plotting clandestine rendezvous with their lovers. There is a beautiful lacquered closet in Topkapi that has a moving tale attached to it.

Ahmed II hears that one of his odalisques has been carrying on with a handsome youth who has been entering the harem surreptitiously. The sultan, enraged, lays a trap for the lovers. Taken by surprise, they flee in terror through the corridors of the harem with the sultan in hot pursuit. When they reach the quarters of the black eunuchs, the lovers disappear into a closet. Dagger drawn, the sultan follows them into the closet. To his astonishment, it is empty. No sign of the lovers anywhere. Convinced that a miracle has occurred, the sultan falls to his knees and breaks into tears. He orders the sacred closet decorated with gold and made into a shrine. But this kind of divine intercession rarely came for violators of the harem rules.

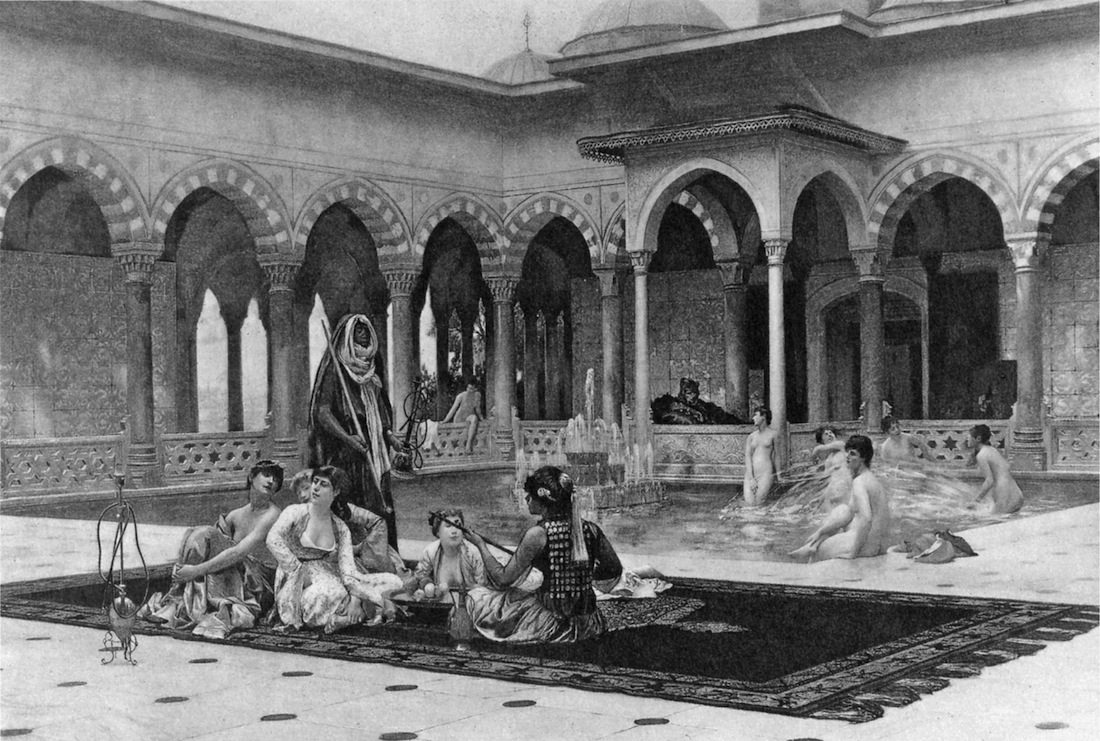

Anton Ignaz Melling, The Royal Harem, Etching reproduced in Views of Constantinople and the Bosphorous, ca. 1815. Melling was appointed architect to Hatice Sultana, favorite sister of Selim III. Although Melling’s drawing is imaginary, it does re-create the daily rituals and customs of harem life quite accurately.

Everything that happened behind the harem walls was tempered by a certain knowledge that once a woman passed through the Gates of Felicity, there was no returning. Let us step now through those gates, into the House of Felicity, the imperial harem of the Topkapi Palace.

Alphonse-Etienne Dinet, Moonlight at Laghouat (“Clair de lune à Laghouat”), 1897, Oil on canvas, 181⁄4 × 285⁄8 in., Musée Saint-Denis, Reims, France

GARDENS

A forest of plane trees and cypresses, filled with roses, jasmine, and verbena, surrounded the gardens. Footpaths led to tiny ponds with floating water lilies and exotic fish, to gilded gazebos and kiosks to shade the stroller from the sun. The gardens were a playground for the women, some taking pleasure in gardening, others simply savoring a leisurely promenade on a warm day. Followed by an entourage of odalisques and eunuchs, the favorites wandered the paths, picking flowers and fruit, eating kebabs and halvah, playing childlike games. In his 1766 account, Observations sur le commerce, Jean-Claude Flachat describes such an outing: “When everything is ready, the sultan calls for the halvet [the seclusion of the area]. All the gates opening onto the palace gardens are closed. The Bostanjis [sultan’s bodyguards] keep sentinel duty outside, and the eunuchs inside. Sultanas come out of the harem and follow the sultan into the garden. Women materialize from all directions, like swarms of bees flying from the hive in search of honey, and pausing when they find a flower.”

John Frederick Lewis, In the Bey’s Garden, Asia Minor, 1865, Oil on canvas, 42 × 27 in., Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, England

GAMES

Most of the games that the odalisques are portrayed as playing seem extremely simpleminded and naive, intended more for small children than grown women—but then, the average age in the harem was seventeen. In a game called “Istanbul Gentlemen,” for example, one of the women dressed as a man, her eyebrows thickened with kohl, a mustache painted on, a hollowed-out watermelon or pumpkin placed on her head as a hat, and a fur coat reversed and slipped on. She sat on a donkey, facing backwards, one hand holding the tail and the other prayer beads made of onion or garlic cloves. Someone kicked the donkey, and off she went, giggling and trying to maintain her balance in a kind of mock rodeo.

Another popular game was a form of tag. One of the girls fell into a pool, pretending she had slipped. As she struggled to climb out, the others tried pushing her back in. If she succeeded in getting out, she chased after the other women, trying to push them into the water. The sultan watched this childish spectacle from his private quarters, often selecting his next favorite.

In another game, which outlasted the harem itself, one of the girls was blindfolded and the others asked, “Beauty or ugliness?” The blindfolded girl chose, and the other girls struck the appropriate poses. When the time was up, she removed the blindfold and selected her favorite player, who started the ritual all over again.

Some daughters of the sultan played with Circassian slave girls they had received as gifts, like live dolls—bathing them, braiding their hair, making clothes for them with the help of their own royal mothers. They taught them things that only a princess should know. When these child-dolls grew up, they often became the attendants of the princesses, accompanying them into their new homes after the princesses were married.

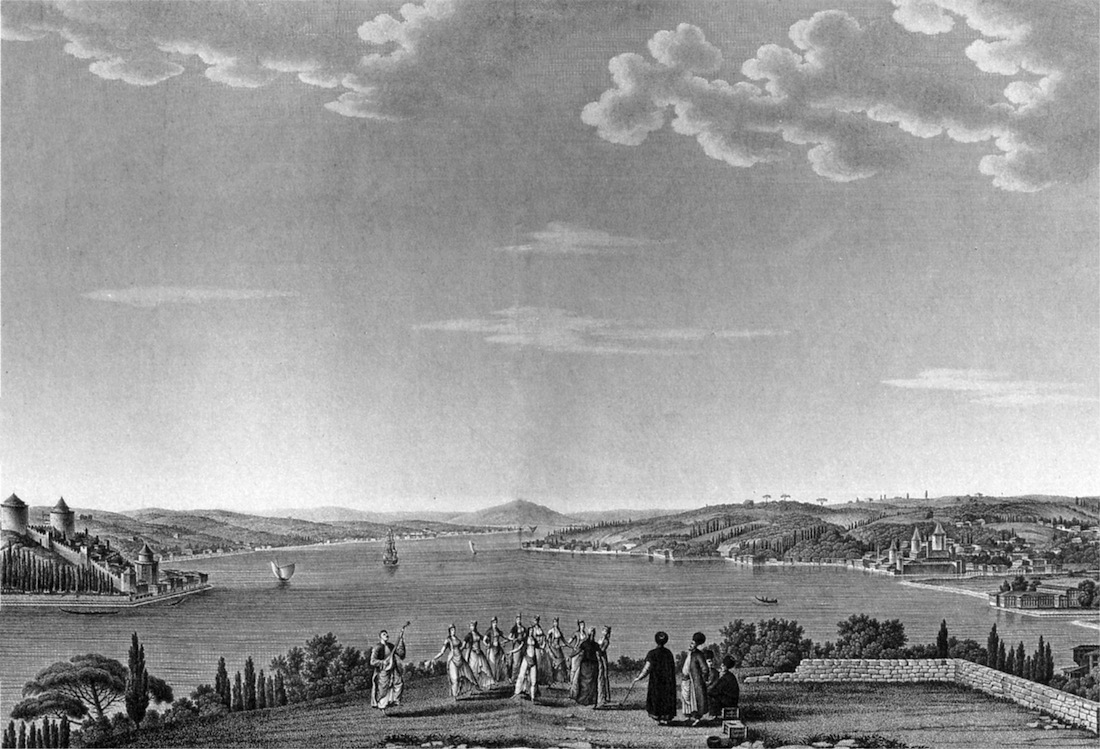

Anton Ignaz Melling, Second View of the Bosphorous, taken from Kandilly, Etching reproduced in Views of Constantinople and the Bosphorous, ca. 1815

During the hot and humid summer months, the women amused themselves in a large marble pool containing small kayiks (rowboats). In another, they splashed and lounged while black eunuchs kept guard. Murad III, a renowned womanizer exceptional even among sultans, watched from behind the arabesques as the naked girls frolicked in the water. Often he invented new games for them. These hours of passionate voyeurism must have had a stimulating effect, since he sired 103 children.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Terrace of the Seraglio, 1886?, Photogravure, 7 × 10 in., Collection of the author

Ibrahim I is said to have thrown pearls and rubies into the water, enticing the girls to dive for them. During his reign, the chief black eunuch had bought a slave girl, supposedly a virgin. But shortly after she entered the harem, her belly began to grow, and she soon gave birth to a little boy. About the same time, Turhan Sultana, the first kadin, also gave birth to a boy. The slave girl was employed as the wet nurse for the young prince Mehmed and moved into the royal harem with her baby son. The sultan was so taken with this healthy and robust little boy, who seemed like such a contrast to his own anemic and fragile son, that he began neglecting the little prince and favoring the slave girl’s son. When Turhan Sultana complained, Ibrahim became enraged. He tore the young prince from his mother’s arms and threw him into the pool. Mehmed survived, but he had a scar on his forehead from this incident all his life.

RIDDLES AND STORIES

It is easy to picture the women taking their leisure by the pools, endlessly chatting with each other for diversion, playing childish games, talking of cennet (heaven) and cehennem (hell), telling tales of fairies and giants. Younger women were spellbound by the narratives of old crones, who would concoct Persian fairy tales and love stories such as Leyla and Mejnun, a tale of the search for a lost beloved, who often turned up in animal form.

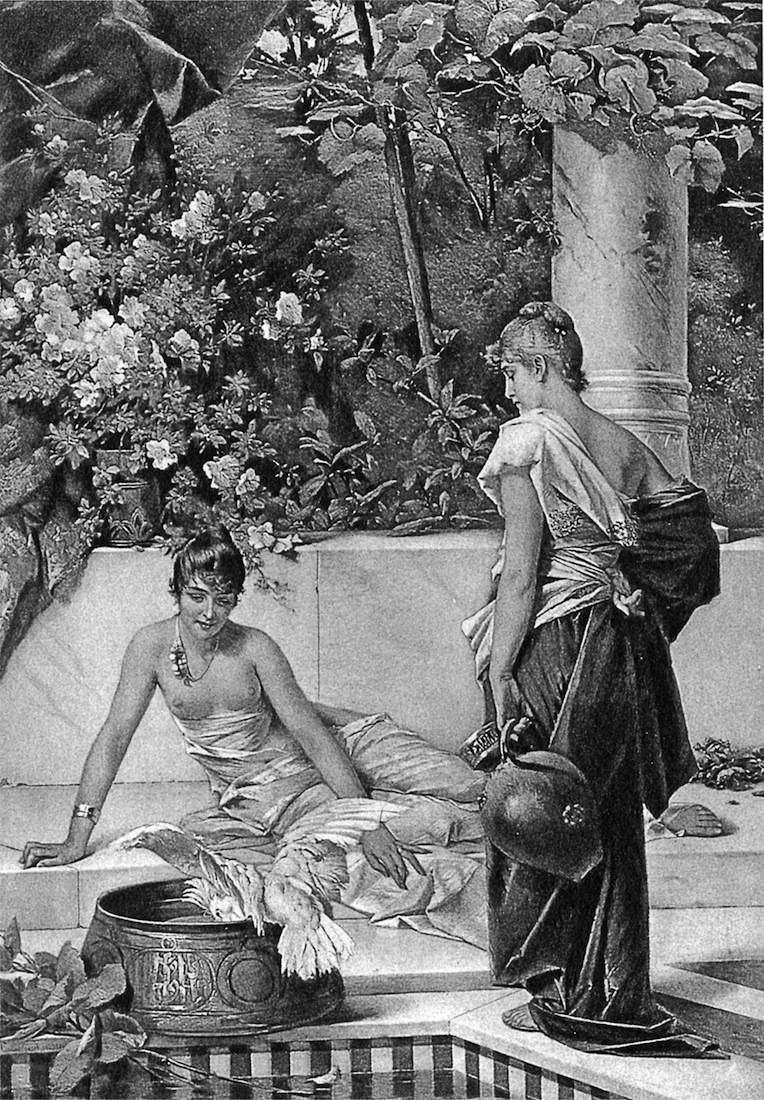

Conrad Kiesel, The Daughters of the Sheik, ca. 1889, Photogravure, 8 × 111⁄2 in., Collection of the author

The storytelling ritual always ended with, “Three apples have fallen from the sky; one belongs to the storyteller, the second to the listeners, and the third to me.” The “me” is presumably the protagonist of the story, with whom the listeners identified.

After sunset and before sunrise, women were not allowed outdoors. That’s when the stories were born. It may be that the women told stories to each other in order to ease insomnia. They also told riddles, which often ended with a threat if the riddle was not solved.

Yellow like saffron,

Reads like the Qur’an;

Either you’ll solve this riddle,

Or tonight your death will take you.

This riddle is supposed to have originated in the fifteenth century. When my great aunt asked it of me—I was ten years old—I was unable to come up with an answer. All evening, I was mortified that Azrael, the angel of death, was peeking over my left shoulder. My grandmother, sensing my terror, whispered “gold” in my ear, thereby delivering me from premature expiration.

POETRY

The women’s dissociation from the world, the surroundings, the quality and pace of their secluded existence lent themselves to poetic expression. Tragedy, suffering, denial, unrequited love were the most common themes. Hatibullah Sultana, the sister of Mahmud II, was banished to a yali (seaside villa) on the Bosphorus as a result of political differences with her brother. Her last poem, “The Song of Death,” is a prophetic and visionary verse that alludes to taking poison and gives the impression that she herself had already chosen her own end: “The River [Bosphorus] is bitter to those who drink its water,” she wrote.

There is an anonymous poem carved into the wall of the harem dungeon, written by a lamenting odalisque who was imprisoned for stealing a cheap mirror. She turned her tears into cryptic verse:

For a two-bit

Mirror lost,

By the men of the century.

It seems that poet sultanas passed their gift to their sons: out of thirty-four sultans, eleven were distinguished poets.

There was a poem my grandmother often recited, with tears in her eyes and a quiver in her voice, that always remained with me. Although the words from Old Turkish were incomprehensible, the emotions were not. It evokes the image of a lonely young woman who sits behind the lattices, recalling the faraway Caucasus Mountains:

| Felek husnun diyarinda, | Fate, in the land of love, |

| Cuda Kuldu bizi shimdi. | Separates us now. |

| Aramizda yuce daglar, | Mighty mountains between us, |

| Iraktan merhaba shimdi. | Greetings from faraway now. |

PRAYER

Moslem women performed ablutions—washing face, feet, hands, and arms up to the elbows—before prayer. They covered their heads and laid a special prayer rug on the floor, and then began prayer by pressing the open palms of their hands over face and eyes, thus shutting out all evil. First, they made an initial bow toward the South, the direction of Mecca, and began the sequence of bending, kneeling, touching the forehead to the ground, and resting back on the heels while their lips moved in silent recitation. Since knees, hands, feet, nose, and forehead must touch the ground during prayer, it was a physical as well as a spiritual exercise—much like yoga.

SECRETS OF FLOWERS AND BIRDS

In John Frederick Lewis’s painting An Intercepted Correspondence, we see a woman caught with a bouquet of flowers. Her act creates a commotion, suggesting an illicit message from a secret lover. Each flower would have been assigned a symbolic meaning. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who had the privilege of being a guest in a harem, was intrigued with this form of communication and later popularized it in England, where it spread like an epidemic. Books were published deciphering the secret message and healing power of each flower and explaining how to communicate through flowers. English ladies quickly adopted the prescribed techniques to aid their own amorous encounters.

The Seraglio also had a substantial menagerie. Children loved playing in the Elephant House, filled with lions, tigers, leopards, and all sorts of other wild beasts, including, of course, elephants. The sultans gave their wives and odalisques monkeys, storks, exotic birds, and gazelles as pets. The seventeenth-century transcendental poets, like Nedim and Baki, likened beautiful girls to gazelles. The gardens boasted coveys of nightingales, canaries, and doves. Colorful parrots and macaws cackled secrets from the private rooms. Abdülhamid II was obsessed with parrots, believing the birds could warn him of evil forces threatening his household. In his Yildiz Palace, cages of different birds filled each room and peacocks wandered the gardens like fantastic watchdogs, intimidating unwanted visitors.

Of all the birds, nightingales were most precious. “Even in a golden cage, the nightingale yearns for its native land,” says an old proverb. For all we know, the nightingale in this eighteenth-century fable may be a prince imprisoned in the Cage:

Once a nightingale loved a rose, and the rose, aroused by its song, woke trembling on her stem. It was a white rose, like all the roses at that time, innocent and virginal. As it listened to the song, something in its rose heart stirred. Then the nightingale came ever so near the trembling rose and whispered, “Ben seviyorum seni gul, gul.” At those words, the little heart of the rose blushed, and in that instant, pink roses were born. Then, the nightingale came closer and closer, and though Allah, when he created the world, meant that the rose alone should never know earthly love, the rose opened its petals and the nightingale stole its virginity.

In the morning, the rose turned red in its shame, giving birth to red roses. Since then the nightingale comes nightly to ask for divine love, the rose trembles at the voice of the nightingale but its petals remain closed, for Allah never meant rose and bird to mate.

OPIUM

Opium is distilled from the white poppy, which grows abundantly in Asia Minor. In its simplest form, it is black putty, sometimes mixed with hashish and spices. More elaborate preparations added ambergris, musk, and other essences. For important persons in the palace, opium was concocted into a jewelry paste, with pulverized pearls, lapis lazuli, rubies, and emeralds. The sultan’s opium pills, of course, were gilded, possibly the origin of the phrase, altin ilac. Was gilding the pill, the Turkish equivalent of gilding the lily?

Most commonly used as a sedative for pain, opium produced euphoric sensations. Some of the sultans and their women took it for the keyf (ultimate fulfillment) brought on by the drowsy peace of the sated senses. The women are portrayed inhaling hookahs, the “elixir of the night.” Amnesia followed; night after night of this induced chronic insomnia. The women began forgetting their distant homes, their lives before the Seraglio. In order to remember, they told stories to one another. At first it was a thousand nights of stories, but even numbers brought bad luck, so they added one.

SONG AND DANCE

The Hunkar sofasi (Hall of the Sultan) is the most spacious and elegant room in the harem, long and rectangular. At one end is a dais over which hangs a balcony. In this room, the sultans received their harem for pleasure and entertainment. One can imagine the Padishah sitting on a throne under a baldachin, dressed in scarlet robes edged with sable. The dagger at his waist is studded with diamonds, a white aigrette in his turban holds in place a cluster of emeralds and rubies, and his bejeweled nargileh (water pipe) is at his side. Before the throne is a carpet embroidered by the harem ladies themselves. The Valide sultana, kadins, and favorites rest on magnificent cushions. A group of odalisques, prohibited from sitting in the presence of the sultan, lean motionless against the wall. The beauty of these women, their exquisite silk and satin costumes enhanced with the most precious jewelry, the opulence of the furniture, all rival the wildest exaggerations of the One Thousand and One Nights.

Mukaddes (dancer on the right) and Muazzez (sitting on her right) with women friends in the courtyard of their house

Here, sazende (female musicians) performed on the balcony, while chengis (dancing girls) swayed before their lord. Dressed in low-necked muslin blouses, velvet vests, and voluminous skirts that opened like fans, they whirled around. The dances were performed in groups of twelve: the leader, ten dancers, and an apprentice. And the performance always ended with the dancers trying to reach a crystal ball suspended from the ceiling next to the throne. The sultan gave gifts to the girls who succeeded.

Selim III was a very fine musician and poet. During his reign (1789–1807) French dancing-masters and musicians were allowed into the outer courts of the harem to teach the girls—novices who had not yet converted to Islam—how to dance. When love affairs began flaring up between the odalisques and their music teachers, the sultans made sure the girls were never left alone with them; they studied in groups, chaperoned by eunuchs.

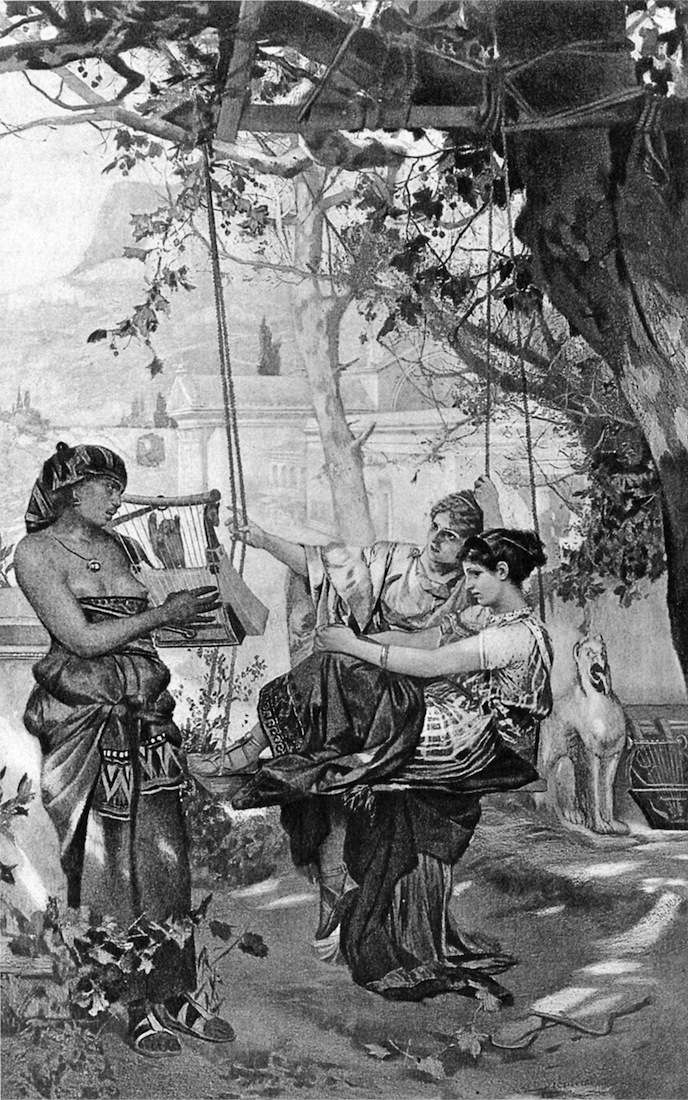

Henri Siemiradski, The Song of the Slave, n.d., Photogravure, 12 × 71⁄2 in., Collection of the author

Sometimes male actors and mimes were invited to perform for the women—always carefully blindfolded, however. The Wilder Shores of Love (1954), a collection of fictionalized biographies by Lesley Blanch, contains a story about the Debureau family (the subject of Marcel Carné’s magnificent 1945 film Children of Paradise):

In 1810, the Debureau family, a Paris troupe famous for their thrilling acrobatic and pantomime acts, was invited to appear before the Sultan. What transpired was a rather peculiar form of theatre: They were ushered through the sumptuous halls into a mirrored pavilion. Absolute silence reigned: it was completely deserted.… The acrobats were mystified. How could they divine that from behind slits in a brocaded curtain the Harem elite were watching? As they hesitated, a turbaned negro motioned them to begin their act. In silence, they spread out their threadbare strip of druggeting, pitiable against the Seraglio’s Persian carpets. They went through their act, proceeding to its climax, a human pyramid. Father stood on uncle, brother supported cousin. Greatly daring, the young Debureau topped the whole swaying edifice, balanced on a ladder.… From the summit, Debureau could look down over the curtain, into the forbidden paradise below. Here the Sultan’s ladies were gathered, “the voluptuous odalisques of the Seraglio … whose very regard could lead to death.” His eyes met those of an unveiled odalisque. Overcome, he crashed to the ground, bringing the whole performance to an ignoble finish.

SHADOW PUPPETS

Shadow world loved shadow plays. Karagöz was an extremely popular shadow-puppet show, full of robustly lewd antics handed down from one generation to another, surviving well into the twentieth century. Sabri Esat Siyavuşgil describes it:

The small screen of thin transparent cloth, hung about with handsome carpets to further conceal the mysterious puppet world behind it; illuminated but motionless, and adorned only with a large picture exquisitely cut and brilliantly colored. Sometimes this picture depicted a galley whose oars, illuminated by the flickering candlelight, created an illusion of movement; sometimes it would be a basket of flowers in a design so stylized as to evoke an admiring thrill from any abstractionist artist; and again, it might be a marvelous and incredible seraglio, tottering and fit to collapse at the first passionate sigh of its odalisques, or burst of rage from its eunuchs.

Karagöz plays were satirical shows with stock characters, often political. The play entitled The Great Marriage, for example, is a parody of arranged marriages in which the engaged couple do not see each other until the wedding night. The play ridicules this custom, which frequently caused a catastrophic row the day after. Chelebi has the laudable intention of marrying off his brother, the town drunkard, to make him give up his vice. Chelebi brings in Karagöz—always an abrasive male character—to play the role of the bride. A traditional wedding takes place, and the drunkard finds himself united in matrimony with a bearded creature. Confronted by this un appealing prospect, he promises to renounce his vice if the nightmare will only end.

SHOPPING

Occasionally, women were given the privilege of driving in their latticed arabas (carriages) to the bazaars. The araba would arrive at the gates of the market, where merchants displayed fabrics, scarves, ribbons, and slippers, and the eunuchs would purchase them. More often, peddlers brought such commodities in large bundles to the Seraglio, where the eunuchs greeted them at the gate, checked the bundles, and presented the goods to the women inside. Fabrics purchased were sent to the palace tailor or dressmaker, who kept a record of everyone’s measurements.

Sometimes, female merchants, mostly Jewish women, were allowed inside the private apartments, bringing not only goods but also gossip from the outside. It was not uncommon for Christian merchants to marry Jewish women so that they could corner the harem market, or for these “bundle women” to become intermediaries for clandestine affairs and palace intrigues.

EXCURSIONS, VISITS, AND OUTINGS

During the reign of Mahmud II (1808–39), a breath of “liberalism” stirred in the air. His mother, Nakshedil Sultana, is assumed to be the legendary Aimée de Rivery, a French girl from Martinique (and cousin to Josephine Bonaparte) who had been kidnapped by Levantine pirates on her way back to convent school in France. Sold to the Bey of Algiers, who gave her as a gift to Sultan Abdülhamid I, Aimée made the best of her unexpected destiny, slowly endearing herself to the sultan and eventually becoming the Valide sultana. During her reign, elements of French culture and etiquette insinuated themselves into the harem.

Women like Aimée de Rivery helped loosen social structures in the harem, allowing for considerably more freedom to venture outside. Although heavily guarded by their eunuchs, the women were allowed to picnic at the Sweet Waters of Asia or Europe, two of the lovely estuaries opening into the Bosphorus. In a Preziosi painting we glimpse the fountain in the Sweet Waters, built by the queen mother Aimée de Rivery herself.

Amadeo Count Preziosi, The Sweet Waters of Europe, ca. 1845, Watercolor on paper, Private collection

The Sweet Waters of Europe, Goksu, was a vast, grassy field along the confluence of the two streams that form the Golden Horn. There, in the shade of walnuts, terebinths, palm trees, and sycamores that made a succession of leafy pavilions, women gathered in circular groups, surrounded by their slaves, eunuchs, and children. In the nineteenth century, pavilions and kiosks built by the sultans to entertain their harems became favorite flirting grounds for the aristocracy.

The women took kayiks along the stream for pleasure trips down the Bosphorus to the Sweet Waters of Asia, the meadow surrounding the Küçüksu stream. Like the Sweet Waters of Europe, it was a popular resort full of lovely yalis (seaside villas). In the meadow, people gathered to enjoy the fresh air; their lavish picnics included roast lamb cooked on spits over an open fire, corn-on-the-cob boiled in enormous black iron cauldrons, acrobats, puppet shows, dancing bears, gypsy fortune-tellers, Bulgarian shepherds playing on their pipes—all amid a field of tulips and hyacinths, gently swaying to the rhythm of the wind.

Such pleasure trips made the harem come alive with excitement. When the day for an outing arrived, the secretary made the announcement and the harem began to reverberate with activity. The women, all dressed in the same color—as required—left in carriages with drawn curtains. They brought along pitchers inlaid with gems and filled with sherbets to quench their thirst, and chanta (velvet bags embroidered with gold or silver) containing handkerchiefs, baksheesh (tip money), alms for beggars, and hand mirrors used in adjusting their veils. Eunuchs on horseback led the entourage and drew up ranks on both sides of the procession. The most important women occupied the forward and rear carriages, with novices riding in the middle.

Occasionally, the women, accompanied by the ever-present eunuchs, took rides into the country, stopping by cool streams to refresh themselves. Popular minstrels and dancers entertained them, but, of course, a curtain always separated the performers from their audience. Sometimes the procession stopped at one of the villas along the way, where the women rested, recited their afternoon prayers, or sat in a gazebo eating fruit from the gardens and yogurt made by famous yogurt makers.

When they returned to the palace, they embellished stories of their adventures for those who had stayed behind. They spun yarns about what they had eaten and whom they had seen, gossiping about things that had not happened but that nevertheless added romance to their lives.

In an interview recorded on the last day of her life (published in Haremin Içyüzü, 1936), Leyla Saz, poet, musician, and harem woman (1850–1936), describes an exquisite outing:

How did you entertain yourself when you were young?

Music.

And dance?

In the palace, we also danced. Prince Murad played the piano and his sister and I would dance the Polka. But our real joy was enjoying the simplicity of nature. We could run away from the city noise and throw ourselves into the water under the moon … Sweet Waters of Asia, Sweet Waters of Europe. Between Bebek and Emirgan [two small towns on the Bosphorus], there were hundreds of kayiks and women in silk and diaphanous veils like apparitions. I can never forget those beautiful days. The crystal voices [of the singers] licked the shores of the Bosphorus, trembling and dying into the water. We hid our emotions even from the moon, closed our eyes, and slipped into a reverie. The dawn found us like this.

The painted and gilded kayiks of those days were luxurious boats with brocaded cushions, Oriental rugs, or velvet carpets richly embroidered in silver or gold, crimson or purple. They rowed up and down the Bosphorus, escorted by a sparkling shoal of jeweled fish ornaments, hirame, attached to the boats by chains, trailing from the stern and out over the surface of the water in a fan of splendor.

FESTIVALS AND SPECIAL DAYS

On the Persian New Year, nevruz, celebrated during the spring equinox, the grand vizier and other important ministers presented gifts to the sultan. In the harem, the women offered their own felicitations and received gifts from the sultan.

In 1554, a Dutch envoy who visited Istanbul brought back to Holland something that would change the nature of its national identity. Ogier Busbecq stumbled upon a secret on the shores of the Sweet Waters of Asia: a field of strange flowers. He had never seen anything like it before, and when he expressed his awe, someone presented him with a sack of bulbs. In the autumn, he planted them on the flats near his home in Holland, and in the early spring, tulips of all colors sprouted. People came from all over to see this miracle, and grew obsessed. Tulipomania spread throughout the Netherlands, almost leading the nation to bankruptcy. Carriages full of bulbs left Istanbul in 1562, arriving at their destination a few months later. This tradition continues to this day. Every summer a carriage loaded with a variety of tulip bulbs treks from Istanbul to Holland—though, over the years, the Dutch have developed their own hybrids.

The name of the flower is derived from the Turkish nickname for it, tulbend, meaning turban. Istanbul was seized with its own tulipomania years later, during the early eighteenth century, known as the Reign of the Tulip. Sultan Ahmed III, who ruled from 1703 to 1730, and his grand vizier Ibrahim shunned war and focused on cultural enlightenment, building summer palaces along the Sweet Waters designed in both Persian and European architectural styles. Beds of tulips and myriad other flowers decorated gardens in a wild riot of colors. Istanbul glowed, and entertainments of unforgettable splendor took place, inspiring great literature. A new level of refinement was attained in the miniature painting for which Ottoman artists of this period, like Levni, are celebrated. Jean-Claude Flachat, the French manufacturer to the sultan, gives a colorful account of a tulip fête in Observations sur le commerce (1766):

It takes place in April. Wooden galleries are erected in the courtyard of the New Palace. Vases of tulips are placed on either side of these rows in the form of an amphitheater. Torches and, from the topmost shelves, cages of canaries hang, with glass balls full of colored water, alternating with the flowers. The reverberation of the light is as lovely a spectacle in the daytime as at night. The wooden structures around the courtyard, arbors, towers and pyramids are beautifully decorated and a feast to the eye.

Art creates illusion, harmony brings this lovely place to life, enabling one to reach the mirage of one’s own dreams.

The Sultan’s kiosk is in the center; here the gifts sent by the palace dignitaries are on display. The source of their origin is explained to His Highness. It is an opportunity to see eagerness to please. Ambition and rivalry strive to create something new. What may be lacking in originality is replaced with magnificence and richness.

On several occasions, the chief eunuch has described to me how the women display all their skills on such festive occasions as this, in order to obtain something they desire or to entertain everyone.… Each strives to distinguish herself. They are full of charms, each with the same objective.… One has never seen elsewhere to what lengths the resources of the intellect can go with women who want to seduce a man through vanity. The graceful dancing, melodic voices, harmonious music, elegant costumes, witty conversation, the ecstasies, the femininity and love—the most voluptuous, I might add that the most artful of coquetries of lust are displayed here.

DISENCHANTMENT

In the late nineteenth century, during the conservative reign of Abdülhamid II, the music ended and the frolicking stopped. Beset with paranoid fears of assassination, the sultan banned all gatherings, including musical performances, kayik excursions, and dances. Heavy black veils replaced the diaphanous yashmak. His reign became a period of social mourning. In Turkey Today (1908), Grace Ellison, a British feminist and journalist, records one woman’s response to this sad development. Halide Edip’s words (1914) speak of the pall that must have descended over all harems, deprived of the distractions that made the life of a captive tolerable:

We are idle and useless and therefore, very unhappy. Women are sorely needed everywhere; there is work that we can all do, but the customs of the country will not allow us to do it.

Had we possessed the blind fatalism of our grandmothers, we would probably suffer less, but with culture, as so often happens, we began to doubt the wisdom of the faith which would have been our consolation. We analyzed our life and discovered nothing but injustice and cruelty, unnecessary sorrow. Resignation and culture cannot go together.

How can I impress upon you the anguish of our everyday life—our continual haunting dread? No one can imagine the sorrow of a Turkish woman’s life but those who, like ourselves, have led this life. Sorrow indeed belongs to Turkish women; they have bought the exclusive rights with their very souls. Could the history of any country be more terrible than the reign we are living? You will say I am morbid; perhaps I am, but how can it be otherwise when the best years of my life have been poisoned?

You ask how we spend the day! Dreaming, principally. What else can we do? The view of the Bosphorus with the ships coming and going is the consolation to us captives. The ships to us are fairy godmothers who will take us away one day, somewhere we know not—but we gaze at the beautiful Bosphorus through the latticed windows and thank Allah for at least this pleasure in life.

Unlike most harem women, I write.… This correspondence is the dream side of my existence and in moments of extra despair and revolt, for we are always unhappy, I take refuge in this correspondence addressed to no one in particular. And yet in writing, I risk my life. What do I care?

Listen to this: How I hate Western education and culture for the suffering it has brought me! Why should I have been born in a harem rather than one of those free Europeans about whom I read? Why should fate have chosen certain persons rather than others for this eternal suffering?

Sometimes we sing, accompanying our Eastern music on the Turkish lute. But our songs are all in the minor key, our landscapes are all blotted out in sadness and sometimes the futility and unending sorrow of our lives rise up and choke us and cause the tears to flow, but often our life is too soul-crushing even for tears and nothing but death can alter this.

Like a true daughter of my race, I start the day with “good resolutions.” I will do something to show that I have at least counted the hours as they drag themselves past! Night comes, my dadi [old nurse] comes to undress me and braid my hair.… I tumble onto my divan and am soon fast asleep, worn out with the exertion I have not even made.