5. Supporting and Regulating Natural Processes

We come now to consider measures designed to improve the vitality of earth and crops—the original biodynamic preparations of Rudolf Steiner1—together with further ways in which biodynamic, homoeopathic and ‘homeodynamic’ principles have been applied. Before concluding the chapter, brief mention will also be made of the original biodynamic approaches for tackling weeds, pests and disease.

The lowest common denominator for these various tasks is that of healing: healing to restore some of the earth’s lost vitality, healing aspects of an agricultural organism which have become unbalanced, and providing protection from environmental stresses.

The biodynamic spray preparations

The biodynamic preparations as originally conceived by Rudolf Steiner, comprise two groups, the field sprays (500 and 501) and those for the compost process (502–507) .2 The word preparation refers to an original process by which these materials are created, and as such rather conceals their purpose. In fact, the biodynamic preparations are activators, enhancers, vitalizers or facilitators of processes.

The field sprays regulate the life of plants in a polar opposite way. Horn manure activates the soil-root realm while horn silica guides the upward development of plant growth. These preparations should be used in combination to bring about balanced growth. But why horns? These were discussed in Chapter 3. We are concerned with their sensitivity to cosmic forces and their capacity to contain those forces accumulated in the manure and silica respectively. We should note that certain Ayurvedic herbal remedies depend on burying material in a horn for a period to strengthen its potency, and traditional doctors overseas still utilize horn caskets for storing their remedies, including snake anti-venom.

As information is available in other sources3 only essential facts will be given here on how each preparation is made and applied.

Horn manure (500)

For this we require cow horns and cow manure. Fresh cow manure is packed into the horns (the core having been removed) (Fig. 5.1). Horns are then buried in good, well-drained soil, at 15–40 cm depth, with open ends turned downwards (Fig. 5.2). Good topsoil with plenty of compost or humus is then placed around and over them rather like the act of planting. This will optimize the working of cosmic energies (Chapter 4). This procedure should take place in autumn, ideally around Michaelmas in the northern hemisphere. This relates to the intensification of the earth’s life forces in wintertime (Chapter 3). The location of the buried horns should be clearly marked to avoid embarrassment later! These should be dug up roughly six months later and their contents either used as below or stored (see Storage of preparations).

Fig. 5.1 Horns filled with cow dung ready for burying

Fig. 5.2 Placement of horns in soil pit

A portion of the material from the horn is crumbled into water in a bucket at the rate of 60 g in 35 litres of water per hectare (or 25 g to 15 litres per acre). For large areas, according to supplies of preparation, the amounts can be reduced. Traditionally this is hand-stirred for one hour, making sure to develop a vortex or cone-shaped depression in the liquid (see below). The material is then ready for spraying. As the forces of horn manure are to be directed downwards to soil and roots it is logical to apply this preparation in the evening when the earth’s flow of energy is in that direction. It should be applied as large drops within 2 hours of stirring, using a bucket and brush (a bundle of leafy twigs suffices), or alternatively by knapsack or tractor-mounted sprayer (Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3 Alternative ways of applying the field spray preparations. Top left: Bucket method. Top right: Knapsack sprayer. Lower: Tractor or ATV-mounted 3-point linkage kit (Lindsay Ellacott, UK)

Horn manure is used at the start of any cycle of crop growing, before or immediately after sowing or planting out. It should also be used after a hay cut or whenever grassland begins a new cycle of growth. In polytunnels, it can be used before the start of any new crop. Horn manure connects with processes governed by the inner planets related to germination, root development and vegetative growth as summarized in Chapter 2. It represents a ‘highly concentrated, life-giving, manuring force’. The latter is the product not only of the original manure’s potency, but of its intensification through infusion with the winter life forces of the earth. Finally, the etheric and astral force of the horn manure needs to be unlocked from physical substance, which is why a particular stirring method is chosen (see below and Chapter 8).

Horn silica (501)

Silica or quartz crystals are illustrated in Fig. 4.1. There are many forms of quartz. Reasonably pure rock silica is good enough for this purpose without searching for perfect crystals! The preparation requires finely crushed silica to be placed into cows’ horns. The silica powder is made into a paste with water before filling the horns. The ends of the horns are plugged with clay or soil to prevent subsequent loss of silica. Horns are buried, as for horn manure, except that the period of highest sun should be chosen—from spring to autumn. This corresponds to a period of out-breathing of the earth’s life forces (longer day-length), for at this time the light ether, to which silica is strongly related, more actively penetrates the earth (Chapter 4). It is this which the ground-up silica will be absorbing.4

Horn silica contains only trace amounts of the original substance and is principally applied for its radiant silica force. It enables the plant to be more sensitive to all those qualities contained in the light of day. It strengthens the form-giving aspect of growth together with quality and nutritive value. Silica enhances the absorption of far-infrared frequencies to which water and organic molecules resonate. This is likely to confer antioxidant properties, which translate into healthier growth and better keeping quality. Horn silica may also be used effectively for the suppression of fungal disease resulting from damp conditions with poor light levels (see also oak bark preparation and Equisetum spray).

A 2.5 g portion of horn silica is added to 35 litres of water per hectare (1 g in 15 litres per acre). Stirring is carried out as below. Spray as a fine mist in the early morning, preferably before dew has evaporated. This relates to the earth’s daily out-breathing, and enables the silica forces to be carried upwards within the structure of the plants. As the practicality of spraying tall plants may call into question the use of this preparation it is worth realizing that silica forces reaching the lower parts will be transmitted throughout the entire plant.

Crops should have a properly established root system before horn silica is first sprayed. It is then best sprayed at stages of growth where a change of plant morphology is noted. As horn silica can significantly influence aspects of crop quality, repeated application at intervals up to harvest will be beneficial.5 Applications soon before harvest, when vegetative growth is no longer to be encouraged, can be carried out in the afternoon.

Stirring the horn preparations

The above preparations require to be stirred into a volume of water before spraying. Steiner’s original guidance, using materials available to him at the time, was to stir in a bucket to develop a vortex (Chapter 8), doing so in alternate directions, breaking down the vortex at regular intervals to create chaotic motion. Stirring is then recommenced in the opposite direction, the whole operation being continued for one hour (Fig. 5.4).

Fig. 5.4 Spiral movement of water into a vortex

One should suspect that more happens here than a simple mixing or dissolving process! Water is a special substance and is able to take on the resonance given to it by materials with which it is in contact. The radiant energy from the preparations is thus transmitted to and absorbed by the water. This process should be complete after one hour’s duration. It may be objected that there can be infinite variation in the stirring process and that one hour is arguably of little consequence. Indeed, there is some suggestion from dowsing that while one hour gives a satisfactory outcome so also do shorter periods. However, one hour is an exact proportion of the way that time governs our lives and one finds that early apothecaries generally never stirred or ground their remedies for less than this time.

Certain changes tend to take place—increase in dissolved oxygen (and bacterial numbers in the case of 500), together with a slight increase in temperature from ambient conditions, human contact and, more importantly, from frictional energy given to the water. Not surprisingly, it is the general experience that there is a change in viscosity after about 20 minutes, and the water becomes easier to stir!

Depending on the area to be treated, the bucket has become the barrel (Fig. 5.5), while hand stirring has given way in some cases to machine stirring (Fig. 5.6). With ever larger farms turning to biodynamics it is essential that efficient systems are in place to deliver these preparations in a timely manner. All this has naturally led to fierce debate among biodynamic practitioners—firstly the replacement of the human being by a machine, and secondly the precise harm inflicted on the water by its characteristics, in particular that of its electromagnetic field.

A further development has been the use of ‘flowforms’ (Chapter 8), which engender no less resistance in certain quarters. Issues have arisen over the material the bowls are made of, the type of pump employed or the precise motions of the water as it flows through the system. Flow-forms, however, were developed through painstaking research of the natural motions of water together with the shapes produced by formative forces.6 Besides a general mixing, many combine a lemniscate motion as water swishes across each set of bowls, with micro-vortices as water cascades from one level to the next (Fig. 5.7). The same micro-vortices are achieved in the succussion process employed by homoeopaths. Flowforms are the most practical solution for delivering large volumes of spray, particularly where a person has to work single-handed.

Fig. 5.5 Barrel stirring. Left: Traditional wooden cask. Right: Plastic drum and tripod

Fig. 5.6 Stirring machine in New South Wales, Australia

Fig. 5.7 Flowform cascade in North Island, New Zealand

While there can be criticism of any large-scale mechanized technique based on assumptions about the energy quality of the resulting water, resistance to machine stirring may simply arise out of concern to defend the original guidance of Rudolf Steiner. A brief evaluation of stirring methods is offered later.

Field spraying—practical considerations

Here, the question of timing needs to be addressed. Current Demeter certification requires producers to apply a minimum of one application of each of these sprays in the course of a year. If one chooses to comply literally with this requirement then it is very important that the respective applications are timely. In the case of the 500 where focus is on the land, coverage can often be achieved more or less at the same time and most will attempt to apply this at the beginning of the ‘growing season’. But one should avoid having a fixed idea of when this spray should be applied, for autumn-sown crops or following a hay cut also represent the start of a cycle of growth. On the other hand, the 501 is more crop-specific, meaning that there is an appropriate time for treating growing vegetables, field crops and pasture. Horn silica then may not lend itself so well to blanket coverage, except perhaps in all-grassland situations. Because it is to be sprayed in the early morning, many do not make full or effective use of it. And as polytunnels become ever more widespread, we need to be flexible and adaptive in our approach to using both the spray preparations and regard repeated applications as normal practice (see Chapter 6).

Are weather and soil conditions of relevance to the application of the horn preparations? There is often uncertainty here. Does it make sense applying horn manure when the soil is too cold or dry? Can either be applied if rain is forecast—or even falling? Should horn silica be applied during drought conditions? We need to realize that these preparations address life processes, which work through the medium of water. Horn manure activates the plant root, its relation to the clay-humus and soil micro-organisms. If soil moisture is scarce there is little, apart from root tissues themselves, that is receptive and therefore able to capture the essence of horn manure. More obviously, little growth is possible. Equally, little benefit can be expected if temperatures are too low for soil biological response. In cold weather, the practice of warming water prior to stirring horn manure may well help to release ether forces but application of the preparation at such times would seem misguided.

In a climate where it is often raining or forecast to do so, one worries about the efficacy of sprays. To apply 501 when steady rain is falling would be absurd, but we are dealing here with radiant energies which, once in contact with plant surfaces, will disperse themselves within the biological tissues and connect to the ‘being’ of the plant. To think otherwise is to adopt the mindset of someone applying pesticide. For this reason application of 501 to the lower foliage of taller plants will suffice, instead of endangering life and limb with the use of steps and ladders. Similarly, we should expect horn manure to penetrate the ground without having to physically infiltrate. However, if the ground is waterlogged the soil is not able to support life processes, so it makes no sense applying 500 at such a time.

On the other hand, if horn silica is applied when plants are under moisture stress there is no support for vegetative growth; consequently there is a risk of premature ripening and reduction in yield. This is a factor which often restricts choice of 501 spray timing within the spring and summer season. But as horn silica assists formative growth and ripening, it may be of supreme value under prolonged dull, moist weather conditions, when it can contribute those light forces which were concentrated in the silica horn. Winter conditions are frequently mild so pasture grass continues to grow and animals can be kept outside provided poaching is not a problem. But these days are often cloudy, damp and gloomy. Is this not an opportunity to use the silica preparation? And if it is considered that temperatures are limiting, then why not combine it with valerian as below. Furthermore, given an inventory of newer preparations (outlined later), for successful growing one should not remain over-reliant on the original sprays.

We should realize that the biodynamic preparations, through their impact on soil and plants, support animal life too. Animals will thus benefit directly from grazing land that has been treated. Often forgotten is the free-range hen which is out all year. In view of recent disease outbreaks we should be redoubling our efforts to strengthen the bird organism.7

The biodynamic compost preparations

Compost preparations moderate the decomposition process and promote the formation of stable humus. They direct the process of plant nutrition through helping plants achieve a balanced use of the different chemical elements. Consideration of the processes they address reveals connections with the various planets.8

There are six of these preparations of herbal origin, four of which are enclosed within an animal organ.9 While these may resemble the original herb material, each has effectively been transubstantiated—it not only has a life quality but also a capacity to sense the needs of plants.10

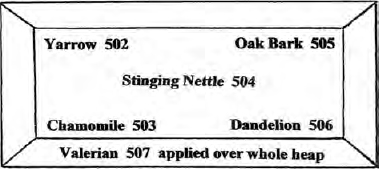

Fig. 5.8 Normal pattern for placing compost preparations in a compost heap

Each individual compost preparation is located separately within the compost either when heaps are half made or at the end, before covering (Fig. 5.8). The reason for this is that their individual influences may better express themselves throughout the mass than if completely mixed. A mere fingertip amount of each solid preparation is sufficient, often introduced into a ball of soil and dropped into individual holes. Diluted juice of valerian is then sprinkled over the entire heap. Compost preparations are collectively referred to as a ‘set’. This consists of 1 cm3 each of the solids plus 2 cm3 of valerian, and is considered adequate for treating up to 8 m3 of compost.

The compost preparations can also be added to liquid manures and slurry. The author has witnessed three different approaches to this. In one, the individual preparations are enclosed in soil or compost and thrown into the barrel. In the second, they are suspended 10 cm under the liquid surface from floating wooden laths tied crosswise. In the third, they are placed in nests of fibrous material which float independently on the surface. In each case, diluted valerian is added. Nothing like choice! But one ought to be reminded that compost, to which we more commonly add these preparations, should be aerobic, so the liquid organic fertilizer must have access to air movement and be periodically stirred to avoid foul conditions lower down.

A description and interpretation of the role of each of the compost preparations now follows.

Yarrow—Achillea millefolium (502)

This is based on the flowers, which are picked in the early morning when they are in full bloom. They are then hung up in the dry during summer. The dried yarrow blossoms are then packed into the bladder of a stag and buried in the ground for the winter half-year. This can be placed between clay pots at a depth of about 20 cm and surrounded with loose topsoil.

Yarrow manifests for the plant kingdom a perfect quantitative relationship between potassium and sulphur, between earthly and cosmic influences on plant growth. Potassium is representative of earthly salts in the sense of the earlier alchemists while sulphur expresses the working of cosmic archetypal forces into the shaping of living matter. No spiritual forces can work in the organic world without sulphur and its crucial role in protein formation. The element relationships in yarrow are said to promote an ideal patterning for this. So the yarrow preparation is concerned overall with the sensitivity of nutrient substances to cosmic forces. With a strong connection to nutrition and with the bladder’s relation to its counterpart, excretion, we see the influence of Venus.

Chamomile—Matricaria recutita (503)

This is from the flowers of the herb which are again picked early in the morning. Only the flower heads should be taken. These are spread out and dried in the shade. They are then placed in the small intestine of a cow, making a number of sausage-like sleeves about 10 cm long. These are then buried over winter in the soil in a protective box which can be packed with peat.

Chamomile’s particular relationship to sulphur causes it to ‘attract’ calcium in addition to potassium. Calcium supports health through linking the life force with the carbon structures of the physical organism (cell communication). In this respect it has a kinship with nitrogen activity. For these reasons the chamomile preparation engenders nitrogen stability within the compost. Intestines are connected with movement processes and, as such, with the activity of Mercury. The ‘caduceus’—a symbol of healing—is associated with Hermes or Mercury. Chamomile is well-known for bringing about a healing effect when the metabolic system has become disturbed.

Stinging nettle—Urtica dioica (504)

The whole herb is taken before it comes into flower. Again, plants are gathered in the early morning. Dig a soil pit, line it with wood, place nettles inside, then put a lid on top and cover with soil. Further nettles can be added later according to availability, but then the full complement of nettles should be covered with soil and left for a full year. No animal organ is required in this case.

Here we progress from processes connected with the alkali and alkaline earth elements to the metals in the middle section of the periodic table. Of major importance here is iron, traditionally connected with the planet Mars. The nettle is said to regulate those processes connected with this element. The nettle preparation influences compost by controlling excessive rates of decomposition. Steiner refers to the nettle as a ‘regular Jack-of-all-trades who can do very, very much’. When talking of the human bloodstream, Steiner connected the force of individuality with iron radiations. This preparation therefore appears to confer on compost and soil a ‘sensing’ for the individual needs of crops. This property, allied to consciousness, is an attribute of outer planetary influence.

Oak bark—Quercus robur or Q. petraea (505)

The oak bark should be taken from the outer or dead woody layer of a mature tree. When broken up into very small crumbs it is then placed inside the skull of a domestic animal: a cow, sheep, goat or horse. The bark should be moistened and put into the hole where the spinal cord begins, then sealed with a piece of the animal’s own bone or a piece of wood. The skull should then be placed inside a protective case and buried in a situation where water is likely to flow past it for a time during the winter period. This can be achieved by a river bank or spring, or where water is likely to be soaking away around buildings.

This preparation regulates excess moon forces which in wet spells have a tendency to cause plant diseases. When life forces are too active, organisms normally associated with decomposition gain access to this surplus energy and begin to parasitize the plant (see also Chapter 3). Oak bark contains calcium, which acts to hold in etheric or life energies. For it to have a healing effect the lime must be taken from where it has originated through life processes. Here in the bark of the oak tree and well above the soil surface, it is in a uniquely living form. The bark calcium is then placed into that organ which has been connected with the animal’s consciousness. Within the skull, the bark experiences the earth’s gathered winter life force under circumstances of excess water, implicitly connecting it with lunar influence. This experience engenders a ‘beneficial contemplative influence’ which opposes the excessive regenerative force so threatening to plant health. In this way, oak bark preparation is prophylactic against plant diseases.

Dandelion—Taraxacum officinale (506)

The flowers of this herb should again be picked early in the morning when they are young and before the centres of the florets are fully opened. They are then laid out to dry for 2–3 days and covered to inhibit the tendency towards seeding. The wilted flowers are then packed into sewn-up bags made from the mesentery of a cow or ox. (The mesentery is the lining of the digestive cavity sometimes referred to as the cole fat.) The individual bags should be about 10 cm in diameter. They are then hung up in the shade for a month inside a protective net. After this, they are stored in a peat-lined box until autumn when, with suitable protection from animals, they are buried in the soil until spring.

The dandelion is described as a ‘messenger from heaven’ as its role is to draw in a cosmic silica force, silica being present homoeopathically in the atmosphere. This enables plants to be sensitive to everything in their surroundings. To accomplish this task a correct relationship between ‘cosmic’ silica (symbolic of the light ether and a connection with Jupiter) and ‘earthly’ potassium must be brought about. Such is the nature of dandelion that this will be achieved through experiencing summer’s influence above ground and the earth’s concentrated life forces while buried in winter.

The significance of the mesentery is that it is a membrane which encases and protects major internal organs which do not experience outer sensations. Such membranes are sensitive and able to store images, and therefore memories. By enclosing in the mesentery, the dandelion substance effectively becomes an organ, retaining outer impressions drawn in by the silica. The preparation therefore enables plants to be highly sensitive to their surroundings and therefore to the organism of the whole farm. A kind of alchemy is involved, for plants ‘then benefit not only by what is in the tilled field, but also by that which is in the soil of the adjacent meadow, or of the neighbouring wood or forest’.11

Valerian—Valeriana officinalis (507)

The flowers of this herb should be picked in the evening when fully out. These have to be minced, then wrapped in cloth and pressed to extract the juice. The latter should be stored in dark bottles with airtight closures. No further treatment is necessary. Diluting and stirring is all that is required. Take 2–3 cm3, or one teaspoonful, of valerian juice and dilute with about 5 litres of water, preferably rainwater. Stir or shake for about 10 minutes before applying as large droplets to the entire exterior of the compost heap. In the case of a liquid fertilizer brew, it is better to add 100–200 ml of the diluted valerian and stir.

Valerian, with its pale blue flowers, harnesses the distant forces of Saturn, closest of the traditional planets to the ‘fixed’ stars—the regions of the plant archetypes or formative influences of the plant world. The association with Saturn indicates that we deal here with the working of the finest of all ethers, that of warmth, traditionally connected with phosphorus. By sprinkling over the compost, the heap is enclosed by a kind of warmth sheath. This is subsequently of benefit to plant growth, for if the ‘warmth organism’ of plants is not sufficiently maintained their connection with archetypal forces is weakened. In alternative medicine, phosphorus has an ego-strengthening effect. In supporting the phosphorus metabolism of plants this preparation therefore strengthens the connection with their own ego or essential formative forces.

Storage of preparations

In general, biodynamic preparations should be stored in a cool, dark place. Use a box filled with moistened peat, as this is the very best material for insulation from extraneous radiations. The box should have a lid, preferably peat-filled.12 It is common practice to place each preparation in its own earthenware pot with a lid. By contrast, horn silica is best kept in a sunny place—usually on a window sill.

Storage should always be a temporary measure for the preparations, as radiating substances will lose their activity over a period of time. They should be regarded as of extremely doubtful potency after more than two years of manufacture. In any case the object of biodynamics is not to make a museum out of the preparations store but to actively deploy preparations on the land!

The human factor in the use of the preparations

As with all methods, rather than simply following instructions, it helps to develop understanding of the actions you are taking, for the human being really does carry a creative force. This leads to better motivation to carry out the various operations, particularly if time presses. It should also improve the effects of actions which are essentially human gestures towards the earth and its life processes. The basic thought to have in mind concerns the earth’s breathing rhythms and the elemental forces which are connected with it. Because seasonal rhythms are disturbed or being lost, the preparations have an increasingly important role in supporting elemental beings.

Science insists that for a technique to be valid the human being should have no effect on the outcome. Anyone doing the work could therefore be expected to achieve the same results—that is repeatability. But for working with living things the human being does interact with the life process and it therefore will matter that a sympathetic attitude is displayed, for example by those involved in stirring and applying the preparations. Here, as in other actions, it is necessary to live in the moment rather than with one’s mind on what has to be done next!

There are many separate operations involved in making and applying biodynamic preparations, so not surprisingly views are held about exactly how this or that operation should be conducted. While there are essential steps to carry out, exploration of previous biodynamic literature suggests that many points of detail are purely matters of opinion or preference. That is human freedom. The only danger is that newcomers may easily adopt certain ‘shibboleths’, not knowing whether they are really essential! The majority of those using biodynamic preparations purchase them from elsewhere, so there is a lack of involvement with or knowledge about the circumstances of their manufacture. It is for this reason that the stirring method attracts so much attention.

However limited one’s understanding of biodynamic measures Steiner assured his audience that they will still take effect, and we are encouraged to apply the preparations as widely as possible. But in addition to what the preparations accomplish of themselves, their use engenders in us a special attitude of mind towards the living earth.13 Biodynamic practices are, however, by no means the only path by which human beings draw close to nature. Particularly in the past, a natural reverence pervaded rural society, while more recently gestures of individual ‘reverence’ have taken different forms, including the use of bird song or classical music played from a tractor.14 Formerly it was said that the best manure was the farmer’s boot, and in China a similar saying referred to the shadow of the farmer. Steiner emphasized time and again the importance of each individual forming a special relationship to what they do. In this case, aspects of biodynamic practice which could be considered imperfect may well be compensated for by a conscious identification with the sacrament being undertaken. Whether in an age of certification Steiner’s ideal becomes more or less difficult to achieve is for individuals to decide.

At this point it seems appropriate to consider how various individuals have chosen to work with, and to develop, biodynamic ideas.

Further biodynamic and related preparations

It should be realized that in his agriculture lectures Steiner was laying foundations for a new agriculture rather than presenting a finished product with validity for all time. In Chapter 3 it was explained why cow manure is of such importance in biodynamic land work. Not surprisingly, various developments have occurred, aimed at concentrating its effects by composting with repeated doses of the compost preparations. Manure concentrates were inspired by Max-Karl Schwartz and Nicolaus Remer who used birch-lined pits (Birkengrube). However, the best known and most widely acclaimed development has been the ‘cow pat pit’ or ‘barrel preparation’ of Maria Thun.

Cow pat pit

This composite material (CPP) is a useful vehicle for spreading the influence of cow manure and the compost preparations on land not normally receiving compost or which is not normally grazed by cattle.15 It is very suitable for land in conversion from conventional to biodynamic management and even for addition to compost which has not received compost preparations. It can be incorporated into horn manure, into liquid fertilizers and is also suitable for seed priming (Chapter 7).

To make it, choose a site with good drainage. Dig a pit 60 cm by 1 metre, and 50 cm deep. Make a bottomless box of untreated timber or simply a wood lining with supporting stakes. These dimensions, while approximate, provide a basic working unit which can be added to according to the quantities required. The upper rim should stand a little above the level of the surrounding ground. The best and longest-lasting construction is made of builder’s bricks (Fig. 5.9).

Fig. 5.9 Brick-lined cow pat pits under cover in Sri Lanka

Five bucketfuls of fresh, fairly firm cow dung are required. If the cow manure is like slurry it is unsuitable, but if a little on the liquid side then it needs to be well aerated and mixed with a little straw. Add at least 100 g of finely crushed eggshells and 500 g ground basalt—a volcanic rock dust. Mix very well to create a dynamic wholeness. Fill the excavation to a maximum depth of 25 cm. Insert three sets of compost preparations (502–506) by pressing them into the manure mixture to a depth of 5 cm. Stir three portions of Valerian (507) for 5 minutes in 350 ml rainwater, then sprinkle over the manure. Cover with moistened hessian sacks so that moisture is retained. Unless the whole operation is under cover, provide with a waterproof lid raised at one side to allow water to run off and air to circulate.

After 1–2 weeks, aerate the manure with a fork (moister mixtures will require earlier and more regular aeration). Add water if necessary but leave the surface flat to avoid excessive drying. The cow pat manure mix will be completed in 2–6 months according to ambient conditions. Cow pat pit is prepared for application as for horn manure (500), but 2–3 times the quantity is normally used, and it is usually stirred for just 20 minutes. If incorporated into horn manure, it is added for the last 20 minutes of stirring, and at the rate of about 50 g to 5 litres (50–60 litres being needed per hectare).

A particular version of this preparation, developed by Christian von Wistinghausen, is known as Mäusdorf compost activator.16 This can be sprinkled dry or watered between compost layers—equally it can be watered over manure or crop residues to assist balanced decomposition.

Podolinsky’s ‘prepared 500’

A further initiative has been that of Alex Podolinsky in Australia. He has created a ‘prepared 500’ by combining the compost preparations with the cow manure before filling the cow horns and burying them. While clearly having different qualities, the latter has a similar application to CPP. It is an attempt to address the impossibility of applying biodynamic compost over wide areas, particularly in the case of Australian farms.17

Hugo Erbe’s preparations

Erbe’s well-known ‘Three Kings’ preparation recognizes the Christian festival of Epiphany (6 January) and, like the other preparations he created, is a sacrament or offering to ensure the continued support of helpful elemental beings. There is in this preparation a real sense that spraying is intended to protect the farm entity within.18 It is just such a concern over the allegiance of helpful elementals that inspired Steiner’s preparations, bequeathed as they were out of a concern for the earth’s diminishing life forces. This argument is no doubt reinforced by the effect of urban, industrial and technological developments in recent times. Hugo Erbe’s creative repertoire included some 21 preparations which involve varying degrees of complexity to make. These include carbon to improve the earth’s breathing process, a preparation to strengthen fruit trees, another to protect them from frost at blossom time and yet another to protect against wild animals.19 Such ideas have now been carried forward in a more user-friendly, homoeopathic way (see below). Erbe also devised a clay preparation for enhancing the forces ‘which mediate between calcium and silica processes’ in the soil.

Horn clay

In the previous chapter we examined clay in some detail. More recently there has been interest in the potential of an intensified clay preparation although this had been anticipated by Steiner.20 As with Erbe’s idea, such a preparation is intended to raise the capacity of the soil to retain and transmit those forces essential to healthy plant growth. Its most noticeable benefits will be where alumino-silicate clays are scarce. Typically, this will apply to sandy soils and throughout the tropics and Australia.21 In the past, marling used to take place in Britain for the remedying of sandy soils—today this is impractical. Even adding clay to compost—as bentonite for example—is costly and without prospect of results unless maintained over many years.

Starting preferably with a high CEC clay, this preparation can be afforded different qualities by burying the clay horn either in summer or winter. It might also be enhanced by addition of basalt rock dust or, if available, the pink potassium feldspar, orthoclase. Where the soil has low clay content a winter-buried horn clay would be suitable, whereas if the soil is very heavy—and often too wet—a summer impulse towards light and warmth might be beneficial. Complementary effects may also be obtained according to whether one is growing roots or seed crops. Using the same basic technique as for horn manure or horn silica, horn clay should be considered part of the biodynamic tool kit and must now be more widely tested.

Therapy for trees

Given the current range of preparations it is possible for biodynamic practitioners to work quite logically towards solutions for many farming and gardening problems. Take the example of trees. Many trees at this time are struggling to maintain their health—they manifest various diseases, deformed growth and pest attack. For a tree, a conventional soil treatment is unrealistic while treatment of external symptoms is an ongoing and often fruitless pursuit. The method described below makes use of the biodynamic principle that the cambial layer of a tree trunk is effectively soil.22 The aim is to give a tree the capacity to heal itself. An approach which has proven highly effective is the use of a ‘tree paste’.

For this, the original recipe consisted of 1 part dried blood, 2 parts diatomite, 3 parts clay and 4 parts cow dung.23 Neither the precise ingredients nor the same proportions appear to matter, so in practice take portions of silica sand (or diatomaceous earth if available), clay (potting clay or bentonite can be used) and a rather larger volume of cow dung, then mix together to the consistency of a thick slurry with some stirred horn manure. Apply this by brush to the base of the trunk as if you were painting a wall, except you will need to rub it in well. Take it up to a height of at least one metre. It will probably be most readily absorbed into the cambial stream of the tree if the outer bark is moist. In some instances abrasive treatment might help but care should be taken not to harm the tree in this way. While giving thought to seasonal flow of sap, it would be worthwhile observing the calendar timing most appropriate for the use required of the tree (Chapter 6).

Ready-potentized preparations

As we have seen, there has been exploration of biodynamic principles beyond the original Agriculture Course. Just as Maria Thun demonstrated the use of homoeopathy in conjunction with insect and weed ‘peppers’ (below), potentized preparations are now available. Starting in the late 1970s, Glen Atkinson and Enzo Nastati, together with Greg Willis and Hugh Lovel, have used various preparations in potentized form to address the concerns of farmers and growers, the theory behind these being largely in the public domain.24 Atkinson’s preparations have been adopted by conventional growers while the efficacy of a number of his preparations has been demonstrated in field trials carried out by New Zealand’s HortResearch. The scope of his products covers the biodynamic preparations and includes the enhancement of photosynthesis, and protection against frost, birds and wild animals.25

Meanwhile, in Italy, Enzo Nastati has long been concerned that the earth’s environment has so deteriorated since Steiner’s time that the existing preparations need to be supplemented and their range extended. Initially set up to regenerate seed quality, over 100 different ‘homeodynamic’ preparations are now available, covering crop nutrition, pest control and protection against climatic and pollution hazards. As with Podolinsky’s ‘prepared 500’, a number of these result from combining the forces of existing biodynamic preparations. In this respect they represent an evolution of Steiner’s original preparations, and their effectiveness is again increasingly supported by field trials.26

How can we compare these materials with the ‘traditional’ biodynamic measures? Certainly there are detailed differences in the way that human beings participate in the process, but it could be argued there is no fundamental difference between the way that traditional preparations are delivered to land and crops and the use of preparations potentized in the manner of homoeopathic pharmacies. In both cases we deal not with substance but with radiating energies, and in either case the response to the earth’s ‘breathing’ process should be the same. If we consider the traditional preparations, these are materials carrying etheric and astral principles (life forces and sensitivity). Before application to the land, however, the necessary volume of water has to undergo an activation process so that it can then convey this force. The difference with a potentized preparation is that the force is already concentrated in a liquid (tincture) which is then simply diluted in water at the time of spray application.

Given the multiplicity of current agricultural problems, potentized preparations offer the producer a flexible and time-efficient holistic approach. Besides their diverse applications, whenever the original preparation materials are scarce or difficult to obtain, potentized preparations offer a solution, together with improved scope for achieving Steiner’s vision of covering the widest possible areas.27 However, while such preparations are ‘permitted for use in organic and biodynamic agriculture’, they are currently not permitted as substitutes for the original biodynamic preparations for Demeter certification.

The use of radionics

Radionics is described as a method for sending precisely defined healing energy to people, animals or plants wherever they happen to be. It is an extension of the principle of healing by the laying-on of someone’s hands. Radionics practitioners are therefore either proven healers or purport to be, as a result of using their equipment. All healthy living organisms are characterized by a particular energy frequency, what we have called here etheric or life energy. In the case of a sick person these energies exhibit abnormal characteristics, so it is the task of the healer to correct them by applying a healing frequency.

A major purpose of biodynamic preparations is to effect a healing and harmonizing process for the earth. Radionic devices—known as field broadcasters or cosmic pipes—are occasionally used to transmit the effects of biodynamic preparations to surrounding land, possibly also using specimens of particular plant pests to actively discourage their prevalence (Fig. 5.10). In this operation it is assumed that the influence of the preparations is continuously transmitted while the device is fully connected. But in the absence of spraying or field-walking, many in the biodynamic movement are opposed to this approach. In extremis, this view claims that radionics works with forces of sub-nature rather than those which are ‘super-physical’ and connected with the realm of life forces.28 However, in view of earlier comments, I would simply say that it expresses a personal relationship to these matters on the part of the operator, who, no less than those applying preparations in the normal way, should be in a position to evaluate its effects—either immediately or in the course of time.

Fig. 5.10 Radionic device, North Island, New Zealand

Evidence of the working of the Steiner preparations

Readers will wonder what effects the application of spray and compost preparations have on farm production and the environment. The immediate answer is that both quantitative and qualitative effects are observed. Having myself presented results of experiments to different audiences, it is interesting that people divide themselves into two camps. There are those who insist that in order to justify the biodynamic method there must be measurable results, while others quickly lose interest when detailing different experiments which show these effects. They are quite content to accept that in a field where we deal with invisible forces we should not necessarily expect to see measurable results. While such an attitude may arise from conviction about the validity of biodynamics, it is not logical, for there is no reason to suppose that invisible energies would not give rise to characteristics that were either quantifiable or in some other way perceptual. Furthermore, as we shall see with the testing of food quality in Chapter 10, there are qualitative as well as quantitative indicators.

Evidence for the effects of the biodynamic way of working abounds in anecdotal form. In countless instances, farmers and gardeners themselves perceive differences in the quality of the land and crops, and some also experience the activity of elemental beings, especially at or after the application of preparations. Reports indicate the responses of wildlife on land treated with the spray preparations, and of cattle concentrated on an area of conventional pasture treated with horn manure for the benefit of a sceptic neighbour.

Experimental evidence for the working of the preparations is of many kinds. Pfeiffer,29 in some of the earliest work, conducted tests on maize and legume seedlings in nutrient solution to discover the root and shoot responses to addition of combinations of the preparations. These showed that when complete sets of the preparations were used there was an advantage over controls, although statistical analysis was not carried out. Perhaps the most remarkable single discovery was that when a standard nutrient solution was made up without lime, the addition of horn manure, chamomile and oak bark preparations compensated for this, as compared with controls. Pfeiffer was also first to show the potential advantage of exposing seeds to very dilute solutions of the biodynamic preparations—seed baths (see biodynamic seed treatment in Chapter 7). He also famously demonstrated, in a box experiment, the preference of earthworms for biodynamically treated soil!

Experiments at different sites have shown that the compost preparation set appears to control excessive heating in the compost heap, while extending the heating period. Ingo Hagel showed that compost preparations sealed into glass vials elicited particular growth responses as compared to controls, thus demonstrating the radiative principles on which the preparations are based.30 Although compost is always variable in its nitrogen content, one study found that biodynamic compost contained 65% more nitrate than the control (due to greater stability of nitrogen), as well as significant differences in microbial characteristics.31

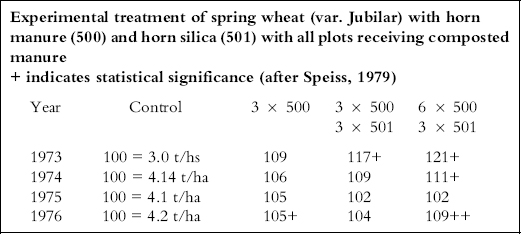

An important body of biodynamic research has been carried out at the biodynamic research centre (Forschungsring) at Darmstadt, Germany on replicated field plots. This has always extended over a number of seasons to reflect a normal rotation cycle.32 Thus, over a four-year period, Abele showed raised crop yields resulting from full biodynamic treatment, as well as higher residual soil organic carbon levels. Speiss demonstrated the effectiveness of biodynamics over standard organic practice in his experiments with wheat, sugar beet and carrots. In the wheat experiment, he showed that repeated applications of horn manure and horn silica resulted in increased yield, which for the most intensively treated plots amounted to a 10–20% gain over controls (see table above). Similarly, E. von Wistinghausen showed that when spinach, bush beans, potatoes, carrots and rye grass were grown with fresh or composted manure and combinations of the preparations the best results, consistently exceeding controls by 5%, were obtained when composted manure was treated with the full set of preparations.

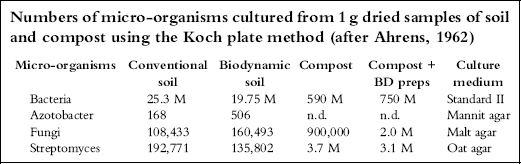

So in the various field experiments reported, one or more biodynamic comparisons have been shown to give the best performance, with the distinct indication that repeated application of the field sprays has a beneficial impact. Part of the reason for these favourable results may well be explained in an earlier study by Ahrens, shown below. Here, in an experiment involving micro-organism culture, we see the balancing and harmonizing role of the preparations, notably in achieving higher levels of fungal organisms.

The Darmstadt experiments are on light, sandy soils of inherently low fertility where small additions of organic matter can more easily improve growth performance. In fact, Joachim Raup and Uli König have observed a pattern in the outcome of applying the preparations to different types of land. While biodynamics scores well on poorer soils it gives little or no quantitative advantage on more fertile land.33 This suggests that biodynamic measures moderate any tendency for lush growth and related pest problems.34 By contrast, they provide more support for plants where conditions are challenging. In this respect, as soil nutrient levels decline, the role of soil fungi becomes more important. Following the Ahrens experiment, it seems that the preparations may be particularly effective in stimulating soil mycorrhizae. This would help explain the success of biodynamics in Australia and New Zealand on poor or degraded soils, as well as more generally in tropical and subtropical areas.

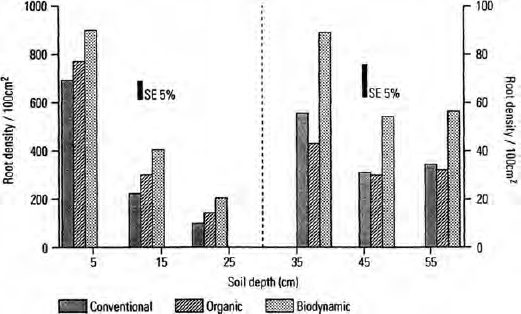

A major study in New Zealand showed that biodynamic farms in general had higher soil organic matter, thicker topsoil, more earthworms, more diverse microbiology, better soil structure and lower soil bulk density than organic or conventional farms.35 A further comparative study of 12 biodynamic and 12 conventional dairy farms in Australia showed that under equivalent stocking the biodynamic pasture on average required irrigation only every 15 days, as against every 7 days for the conventional farms.36 Long-term experiments by Pettersson and von Wistinghausen together with more recent work by Mäder and colleagues clearly demonstrate the benefits for soils and root systems under biodynamic management.37 Bachinger, at Darmstadt, conducted detailed studies of root ramification on soil cores from plots managed according to conventional, organic and biodynamic practices. These showed consistently higher root densities at 5, 15 and 25 cm soil depth for the biodynamic plots38 (Fig. 5.11). There is, then, convincing evidence on the basis of long-term experiments that biodynamic management leads to the improvement of soil characteristics. A prime contributor to this success must surely be the use of horn manure.

The question is often asked whether different stirring methods render the preparations more or less effective. Research based on replicated plots with wheat carried out at Emerson College, UK by Freya Schikorr39 showed firstly that stirring gave a significant yield advantage over those treated with unstirred preparation, and that hand stirring produced a better result than automated machine stirring and flowform methods. Recent work also concludes that hand stirring is superior to machine stirring but a full evaluation which includes different types of flowform is still awaited.40

The scope of this chapter unfortunately does not allow justice to be done to the increasing amount of high quality organic and biodynamic research being carried out and to the considerable collaboration which is taking place particularly between Institutes in Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Austria.41

Fig. 5.11 Root density under different management systems (after Bachinger, 1992)

Weeds, pests and disease

If one is to foster biodiversity as well as support nature’s invisible forces, it makes little sense adopting a hostile approach towards organisms that interfere with land work. Although the environment as a whole may be in a state of flux, plant disease and pest problems can also reflect an unbalanced or failed farm organism. The first stage is to establish whether a particular problem is peculiar to the current year or is perennial. For example, weeds in a horticultural operation are usually more of a problem in a wet year, but if they are perpetually a serious issue then one needs to be critical about the way the land is currently managed and be aware of wider issues besides.

Here, the biodynamic approach to weed and pest problems outlined by Rudolf Steiner will be briefly mentioned.42 In the Agriculture Course, Steiner particularly notes the influence of the moon on fertility and how strongly this works through the element of water.43 Living organisms, including the seeds of plants, encapsulate this lunar force. If this life energy is passed through a fire process—the opposite pole to water—a negative and suppressive influence is brought about. Maria Thun has found that fermentation, also a destructive process, can have a similar effect.44

Burning or fermentation of weed seeds

These methods involve the destruction of the seeds of unwanted plants and the application of the processed material to the land to inhibit subsequent growth. One method involves burning seeds, then either scattering the ashes or making a homoeopathic potentization to the eighth decimal (D) potency. The alternative method involves fermentation of the whole plant with its seeds and then applying this material as a liquid spray. With this method, the nutrients extracted by the weed species can be returned to the land, for the presence of weeds can be an indication of nutrient deficiencies or other soil limitations. The ashing method will be described.

Weed seeds are collected, preferably around full moon, and burnt in a hot fire to ensure they are properly ashed. A metal or other suitable bowl is used for this purpose. Take the ash and grind in a mortar with alternate clockwise and anticlockwise motions (known as dynamization). The dry powder, known as a weed pepper, is applied to the land early in the growing season and will usually need to be mixed with sand or more wood ashes to increase the volume for scattering.

Alternatively the ash can be potentized, a process of successive dilution and shaking used in homoeopathy. Add 1 part of ash to 9 parts of water (by volume). Shake rhythmically in a closed vessel for 3 minutes to obtain the Dl potency (a process known as succussion). Systematically continue this process until D8 is obtained, building up volumes as you progress in order to have adequate D8 for spray application. Spray D8 as for biodynamic 500, using 10–40 litres per acre depending on spraying equipment. Larger volumes can more easily be stirred, creating a vortex, or shaken by using a tipping barrel arranged on a pivot.

The method is best described as one of regulation rather than eradication. While such treatments usually require to be repeated, perhaps for a second or third season, it is reported from New Zealand, for example, that one drop of dynamized seed ash made to D8, then one drop of D8 in 500 litres of water has suppressed nodding thistles within one season! Others, it is fair to say, have not had such immediate rewards.

Insect and mammal pests

For insects, burn a quantity of the particular pest or pests when the moon is in front of the Scorpion constellation and the sun is in the Bull. For slugs and snails, collect at a time when they are often most active—when the moon is in the Crab. Ferment for four weeks and apply when the moon is again in the Crab. Burning a quantity of slugs at this time, followed by homoeopathic potentization to D8, is another possible method.

For warm-blooded animals, rodents for example, the skin is the important part, although the whole creature could be burnt. For birds, the feathers are taken. The burning is done using a wood fire. Warm-blooded creatures are burnt when Venus is in Scorpion. At this particular time reproductive energies are concentrated, so burning brings about a strongly negative force to which wild creatures are sensitive. These effects may be reinforced when the moon is in the Bull. The ashes are crushed and then ‘diluted’ using sand or soil. This is then sprinkled around the areas to be protected. Ashes can be potentized to D8, if spraying is preferred to dry ash application.

Readers may be disturbed by these approaches, which are reviewed here to provide a complete picture of measures originating from biodynamics. The first and most obvious point is that no one should carry out practices if they have serious reservations—indeed, if they do, the method may be rendered less effective! Certain issues concerning animals were discussed in Chapter 3 and will not be repeated. Here, we should merely reflect that these methods have features in common with traditional practices and it is above all necessary to bring the right attitude of mind to bear. For those who may regard the use of cosmic timings as weird, it should be said that just because we live and work in an intellectual age does not eliminate their effects. On the other hand, to use them effectively requires reference to a biodynamic calendar which will be discussed in the next chapter.

The use of Equisetum tea

This material, otherwise known as horsetail or preparation 508, is used as a prophylactic measure, strengthening a variety of field crops and fruit trees against fungal disease such as mildew and rust. While horn silica acts in a largely non-material way, enhancing forces connected with the silica process in plants, Equisetum tea provides a quantitative input of silica. The ash of Equisetum is rich in silica. Though not commonly regarded as a plant nutrient, silica is nevertheless recognized as a protector against fungal attack. It inhibits the formation of phenolic toxins in leaf cells resulting from the action of fungal enzymes.

Collect the branching shoots of horsetail (like little pine trees) shortly before sporing. At this time the plant has its highest silica content. Use fresh or dried. If necessary, store the herb in a dry, dark place. Boil in water to make a decoction or tea. Take one part of herb to ten parts of water (two good handfuls in a pan of water), bring to the boil and simmer for about 20 minutes. Allow to cool, strain and dilute one part of tea to two parts of water. Alternatively, if using dried horsetail, 30–50 g is milled and then allowed to simmer for 1 hour in about 1 litre of water. The resulting decoction is then diluted ten times. In either case a brief vortical stirring could be carried out. Equisetum tea is mainly used in anticipation of cloudy, damp weather with low light levels. During such periods it should be applied as a fine mist in the morning at weekly intervals.

Animal health

Finally, a few brief points should be made about animal health and disease. We live in difficult times regarding contagious diseases, from avian and swine influenza to foot and mouth disease and blue tongue. If global warming proceeds as a trend, our animals will no doubt continue to experience diseases to which they have not previously been exposed. Whatever ideals are espoused on organic and biodynamic farms, the latter exist within a wider national and global agricultural community. In such a context, to vaccinate would seem preferable to hideous mass culls. This is not to subscribe unreservedly to vaccination for, as with human beings, other problems could result from it.

Nevertheless, susceptibility to disease is a function of the health of the organism and the strength of its immune system. Feed quality and levels of stress are crucial. With biodynamic methods, and in particular the use of horn silica, biodynamic farmers have the capacity to raise the value of feed to the highest level. It is also the case that, following Steiner’s final agriculture lecture, we need to become more sensitive to the dietary needs of our now highly domesticated animals. In this way we can creatively raise the vitality of animals for the purposes they are intended.45

Animals on organic and biodynamic farms are, as far as possible, given homoeopathic remedies and natural products (such as cider vinegar and garlic for internal parasites), rather than resorting to allopathic intervention. The latter inevitably disturb the immune system. To supplement existing strategies there is now a widening range of potentized preparations, mentioned earlier.